MARCH

Sky Dance

MARCH IS THE WET MONTH, when the sound of melting snow and ice fills the woods. It’s the time of year when I anticipate seeing and hearing those familiar species I’ve temporarily forgotten during their absence over the winter. These are the days I go walking through puddles and stepping on icy skids along neighborhood sidewalks. In the woods, I love long hikes over crusty snow and short meanders through soggy meadows. It’s the time of year to find shy woodcock, boisterous robins, and curious pine warblers.

Even though the days in March are still cold, there is that promise of a better day just ahead, a day that awakens latent memories of what it was once like in warmer weather. A noticeable increase in daylight now quickens the pulse with the brighter light. Today may be wicked, with fierce frigid winds and driving snows; yesterday was clear and calm. I anticipate tomorrow. It is all unsettled, just as any time of significant change always is. Doesn’t this unsettling cause the March winds for which the month is so well known?

I welcome the first day of March the same way I embrace an old friend who’s been gone for many months. I long for March the most of all the months on the calendar because I know it always ends with the great migration. March begins the spring that most of us know: the time of noticeably longer days, sugar-maple buckets placed on the trees, the year’s first robins, and birds singing early in the morning. Birders know that spring has been with us all along, but it isn’t until March that everyone sees it.

I AM AWAKENED BY THE ROAR of air through a thousand wings. Crackles! They are everywhere. It is a tremendous flock of hundreds and hundreds of grackles. These big black birds fill the air, whirling around in synchronicity; from all sides, front and back of the house, they land all at once. It looks as if the trees have dropped black foliage on the ground. I carefully approach the window, but they see me and explode into thundering flight in an instant. I look out and watch as a funnel cloud of grackles, red-wing blackbirds, and some starlings spiral out of view.

Yesterday a real March wind kept me from deep sleep. At times it crashed through my woodlot like a wild stampede snapping branches under flailing hooves; it stirred up leaves from their winter slumber, scattering them like a frightened crowd of onlookers. When I awoke in the morning feeling exhausted from the restless night, I lay on my back for a while, looking straight up and over, out the window and at the top of my towering oaks. They swayed back and forth, their branches grating against one another with each violent gust. I listened to their eerie music until eventually a more harmonious and calm mass of air ushered in silence, and I fell back to sleep.

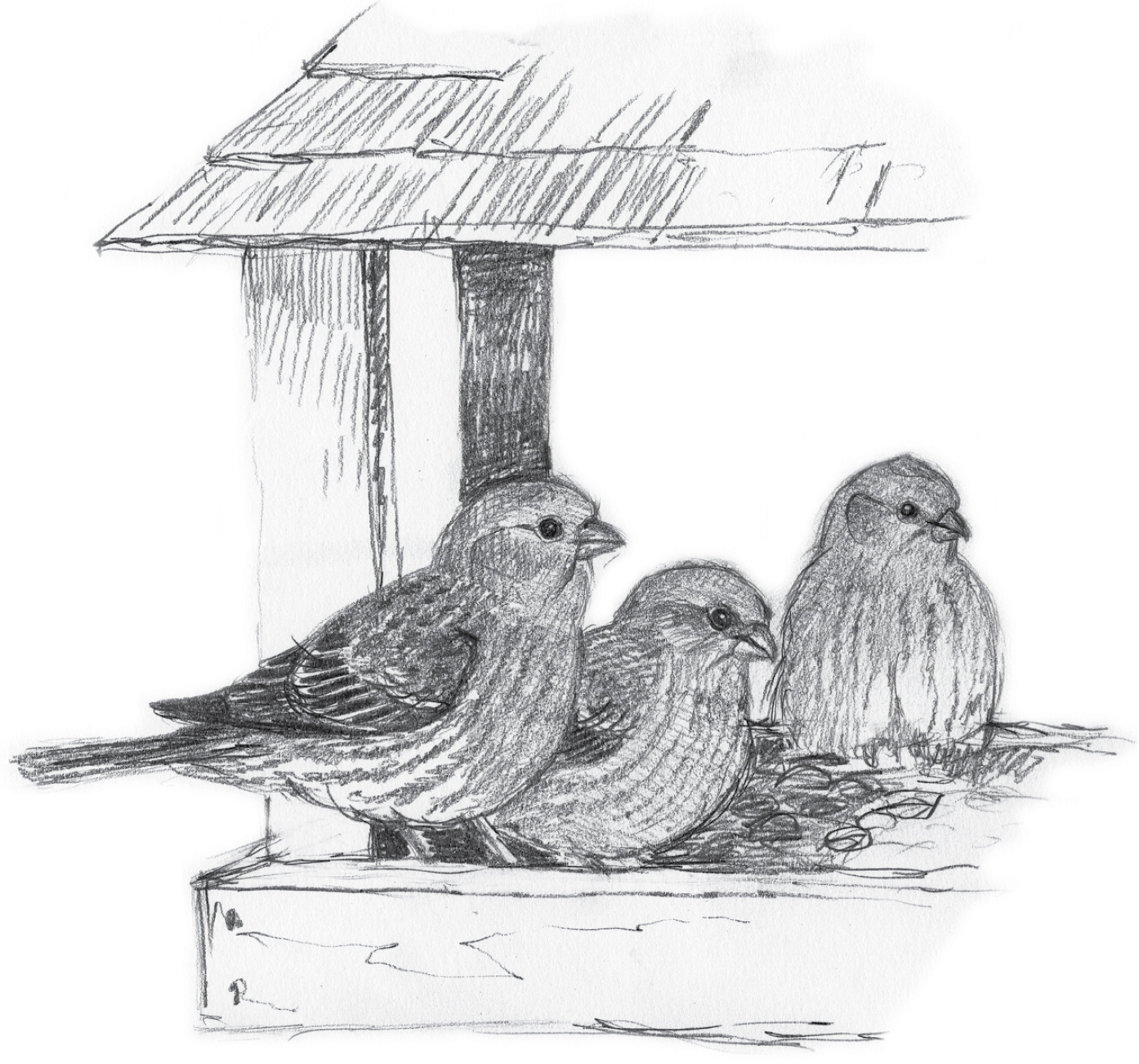

I’ve been hearing the gentle song of the house finch for the past couple of days; the song seems to be getting richer and lasting longer with each passing day. I like it because the song reminds me of years past. We saw many more house finches back in the seventies and eighties than we do today. The reason for their decline has to do with their interesting history. This brown-streaked bird, with its brilliantly colored burgundy head, made its way from the West into New York City via the pet trade. They called it the Hollywood finch, although the accepted proper name was and still is the house finch. It was a good seller until 1940, when it became illegal to capture and sell wild birds. During that year, pet-store owners set their birds free and thereby introduced the species to the East.

It was not long after this that reports began to surface of a strange red-headed sparrow-like bird frequenting shade trees on Long Island. From 1941 until 1947, people often claimed to have seen these birds at various locations on the island; then, in 1948, a specimen taken in Hewlett, Nassau County, confirmed what the public had asserted all along. People had indeed seen a new species, and what they described as a red-headed, sparrow-like bird was actually the house finch. This same specimen, the first free-ranging wild eastern house finch to be captured, remains in mounted form in the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

It didn’t take long for the species to propagate and move off the island. By the early 1970s, the finch was one of the most abundant birds found at backyard feeders in Connecticut, just across Long Island Sound. But the arrival of this formerly western bird into the Northeast was not without its side effects. The similar-looking purple finch was subsequently displaced to rural conifer forests, which house finches avoid. Purple finches were once prevalent in fragmented mixed-deciduous woodlands and even nonforested suburban locations. Another ramification of the house finch’s appearance in the East has been the decline of the notorious (and exotic) English sparrow from urban and suburban bird feeders due to the finch’s aggressive feeding habits. While neither species is native to Connecticut, the house finch is at least native to North America. It is the lesser of two evils, you might say.

Many birders remember the days when their feeders were covered with house finches, but a virus called Mycoplasma gallisepticum, which first appeared in the counties surrounding Washington, DC, in 1993, swept through the population. The virus causes conjunctivitis, which results in respiratory problems and significant vision loss. Although they are not nearly as abundant today as they once were, house finches continue to visit most local feeders. They do not appear to be very common in southeastern Connecticut where I live, but I’ve heard reports of flocks in the towns northeast of here. I see a few every so often, and I do hear that one familiar bird singing every day now. Although I like the sound, I’m not sure if having one nest near here would be so thrilling, since I wouldn’t want the bird to displace a chickadee or even my bluebirds from a nesting box. Perhaps someday the Hollywood finch will return to feeders everywhere but in more modest numbers this time around.

House Finch

IT LOOKS LIKE ANOTHER snowstorm is headed our way. The European computer model has called for a major snowstorm to head farther north than has the American model for several days now. Everybody I talk to has had enough after the big blizzard last month. I haven’t really given it much attention because it’s all going to melt within a week or so anyway. The long-range forecast shows some nice-looking unseasonably warm days ahead, and I can’t wait. I have decided to get a good long walk in, though, before the roads once again become covered in snow.

I always see the red-shouldered hawks when I walk in the spring because this is the time of year when they’re courting. Each day they take to the skies above the neighborhood and pierce the cool air with their sharp cries. I watch them closely. Wheeling effortlessly, higher and higher, they rise until they’re nearly indistinguishable from the sky. The male’s been showing off lately by attaining unthinkable altitudes. I’ve often witnessed the male ascending alone, spiraling upward on some unseen thermal, until he’s completely out of my sight and beyond the earthly domain. Twice this spring I’ve seen him fall from thin air, gain speed in the descent while calling loudly, and then shoot across the neighborhood just above the trees as if he were an errant missile. Once he’s landed safely, the female, having seen the display, flies toward him and allows him to show her various territorial sites. Today, she was clearly so impressed with his death-defying flight that she allowed him to perch by her side for several minutes.

I feel fortunate to have this incredible hawk close to home. Red-shouldered hawks are declining throughout much of their range; like so many birds, they are losing habitat. I’m happy to report that Connecticut’s red-shouldered population is stable, but the state’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection is still eager to learn of any nesting hawks. According to Connecticut wildlife biologist Julie Victoria, fifteen red-shouldered hawk nests were reported in my region last year.

Since I’ve noticed a few hyacinths poking up in neighborhood gardens over the last few days, I decided to see if any were making their way out of the soil on my property. Years ago, Heather and I planted assorted bulbs along the stone wall in the front yard. A few of them persisted despite my neglect, and every year now I find a hyacinth or two—but none just yet. As I make my way back to the house, I find instead the fresh green shoots of what I believe are day lilies emerging through the oak leaves in the round garden along the driveway. Encouraged at the sight of the lily shoots, I decide to walk down to the swamp in search of more green promises.

I see green sprouts in small points scattered in the icy pools between the tussocks. I knew they would be there. The skunk cabbage is always up first. It never ceases to amaze me how this plant can be growing even as winter still packs a punch. Yet there they are, already thriving, with their hoods tight, spathes yielding the bulb-shaped blossom spikes, ready to unravel the giant green leaves. In about five more weeks, those lush leaves will greet the spring sun, and the greening of the land will have begun.

The skunk cabbage is the first spring flower, but it is often overlooked, hidden in its inaccessible boggy habitat among the ice, snow, and mud. A fascinating plant, the skunk cabbage actually generates its own heat, melting its way through the frozen muck and up through the snow. The heat is a by-product of the plant’s respiration: the process of converting food into energy to make sustaining nutrients available.

On my way back to the house, it begins to snow, and just like that, the feeling I got from the sight of the green plant life is taken away from me. The inkling of spring is gone. March is like that. Now I mentally prepare myself for what I hope will be the last substantial snowstorm of the season. It snows lightly off and on all day. Before I go to bed, I look out the bay window to see that it is now coming down steadily under the streetlight. From my bed, I can see well enough through the window into the darkness of the backyard to make out a few white flakes, some being blown onto the screen. I am warm under the covers. Let the snow keep coming. I shall deal with it in the morning.

I am drifting, my eyes are closed, and I begin to think about a partially hidden robin’s nest that I noticed last spring and again today as the snow was falling. It’s sheltered within my spruce tree out front near the fly-through feeder. It’s been there all winter, getting covered in snow with each passing storm and withstanding cold rains, ice, and high winds. On one particular morning, I witnessed a white-footed mouse scurry from its huddled warmth. For two years, a pair of robins returned to it and raised a brood while filling my days with song.

It’s morning now and the snow is coming down hard. I look out at the nest today and project the vivid pictures in my mind of those robins on my lawn. Images of green grass and yellow dandelions flash before me and contrast with the white world covering the yard. This May memory is a tonic against yet another big snowfall. I often wonder where in the world the robins might be. Would they make it back from Central America this year?

Some robins, seemingly more fortunate than others, respond to instincts that drive them no farther than the American South. Either way, the traveling back north is dangerous. They will endure storms, skyscrapers, and cell towers, and when they finally rest, they will have cats and hawks to avoid.

I can pick my robin out from the crowd. It’s always the one that stops running the yard and finds a high perch from which to sing; the others are just migrants passing through. At this time of year, I typically see half a dozen of these red-breasted harbingers of spring in the yard at once. Last year it was the ninth of March when the first wave of robins settled down over my neighborhood. My pair was not among them. My robins showed up later, on the eighteenth.

I HEARD A SONG SPARROW singing today. It’s March 12, and the snow from last week is still here; it’s melted only in places where evergreens sheltered the ground. I won’t see robins working the lawns like I did last year at this time, although I did see three robins on a bare patch of sidewalk on nearby Buckhalter Road. It will be a while before all the snow melts; there is just so much of it. When the robins first started nesting here, the male returned earlier than most of the other robins. My guess is that he was young and needed a head start to defend his territory against the older robins.

The vast majority of wintering robins are actually comprised of juveniles trying to get an edge on spring breeding territories. Birds that do not migrate have a significant advantage over those that do. These birds can begin finding, defending, and attracting mates, and territory, earlier than the migrating birds can. The risks are high, though, and many do not make it through the winter. Robins are very early nesters and therefore often choose evergreens. They particularly favor pines for their sturdy branches because robins love a good secure base for their nest. Another favorite is the honeysuckle shrub because they leaf out early in the year. I don’t look too hard, though—a robin might just decide to nest under my own roof. They often find a ledge beneath an overhang or over a window. In a very short time, they will be here singing in the sun’s warmth, and the light intensity will be noticeably stronger, but somehow it just won’t be a perfect spring day until robins are roaming snow-free lawns.

The way I locate a nest is by looking for a female with nesting material and watching where she takes it. I’m always successful with this method. A robin with mud on its feathers is most likely a female that’s in the process of building a nest, and you can often follow her back to her nest. Another method is to look for a robin that frequents the same part of the yard and see if it becomes nervous when you approach. A female that gets alarmed and starts into a long series of high-pitched distress calls no doubt has a nest hidden somewhere close by.

You can tell a male robin from a female robin by his blacker head, crown, nape, and back; be sure not to mistake darker-phased Canadian robins for these males. I often see the darker robins found in the Canadian Maritimes while they’re on their way farther north. They show up here in Connecticut in small flocks wherever bare, snow-free patches of lawn have thawed out.

American Robin

EVERY YEAR I ORGANIZE a spring bird walk for some of my enthusiastic column readers. Some years the walk turns out better than expected. One March, I led a small group into the cool spring air in search of an unusual bird. It was just before the fall of dusk, and we had worked our way quietly into a wet meadow to search for the American woodcock. We could hear a few spring peepers off in the distance and detected the faint smell of thawing earth.

Like kids, we were all caught up in the magic of the spring air at dusk. We could feel the excitement of knowing that soon it would be dark, and we enjoyed the pure mystical quality of the evening. Perhaps that’s why we eagerly ventured through the meadow, walking ever farther into the shadows instead of retreating. We waited patiently as the light faded, and then we heard it. At first it was soft and distant, but then it grew louder and more distinct. The group fell silent because we were now ready for the show. At exactly 6:45 p.m., the performer flew in from some distant thicket. The entertainment was about to begin. An electric-sounding overture similar to the call of the nighthawk began to fill the advancing darkness.

We all recognized this call, so we watched the horizon for the woodcock’s abrupt ascent; at such times, the bird can be spotted and readily observed. We could see it spiraling higher and higher over the meadow and, after singing for a few brief moments above us, it suddenly fell in a flurry of ruffled feathers. It looked as if it had been shot, but just before impact it spread its wings and landed safely.

We watched this again and again until the darkness was too black to see; the bird fell silent. The group also remained silent while we walked back to the road. We instinctively cast our flashlights on a vernal pool, hoping to see some of the tiny frogs responsible for the deafening chorus we could hear all around us. Like sleigh bells, the wood frogs and peepers rang loudly.

A late-March night is filled with magic—who would fail to turn their ear to these sounds? Soon the spring will advance, and dramas such as the honking of geese, the ringing of vernal ponds with tiny frogs, and the warbling of the woodcock will wait no longer. Inspirations such as the woodcock’s sky dance will then be lost with the setting summer sun. And with that thought, I realize the significance of the wait for warmer days and appreciate this moment called March. The snow has melted now, but the days are still very cool, and the nights get down deep below freezing. I scheduled the woodcock walk for the second week of April this time. It’ll be a late spring this year. I know it.

The woodcock is famous for its acrobatic courtship flight; poets have described its flight and peculiar call throughout history. This plump, hen-size game bird with the long, slender beak arrives on cool, damp evenings in late March and early April after traveling from South America. Exhausted and hungry, these birds begin their secret lives in Connecticut by searching for earthworms and courting mates in the dim fading evening light of our spring.

Woodcocks are brave to be here so early because a late-winter snowstorm can really spell disaster for them at a time when they are especially vulnerable. Indeed, all early migrants face this dire possibility. The skies of March may bring snow or rain, but nothing can stop the woodcocks and other early migrants from returning to us. What begins with red-winged blackbirds builds into an assortment of incredibly beautiful and unique species. Whether common or uncommon, by this point they have begun to restore the land’s vibrant pulse of life.

American Woodcock

MY EYES ARE SHUT TIGHT, but I am no longer sleeping; I am somewhere in between, feeling refreshed and getting ready to plan for the day ahead. I hear a bird singing, a light gentle warbling, a bird I know but can’t quite place. The music it makes gives me a good feeling. I know this is a pleasant and welcome sound. It seems to be coming from the front of the house. Is it a bluebird?

Today is March 25, and it will be a busy day. I am comfortable under my cover, but I must begin my day. I try to be self-disciplined and anticipate a vigorous swim at the fitness center before I go off to work. I detect light through my eyelids and feel a sense of awe at the light’s intensity. The season’s really advancing now, and the urge to indulge in winter sleep is behind me. The light gives me the last and final inner command to open my eyes and sit up. I pull myself from my bed and make my way to the front window to see just what bird is greeting the morning with that faint distant song. Before I get to the window, I realize it is the song of a bluebird. I remember that song now.

My forehead, nose, and hands are cold as I press them against the window, looking everywhere for the mysterious bird. I can see directly below through the rhododendrons—nothing; I scan over Dave’s lawn and high up in the oaks, but no bluebird. I’ve been through this before. Bluebirds are just like that. You either see them as plain as day or you can only hear them singing from an unknown perch. Their early-spring warbles are ephemeral, as fleeting as the warmth of a spring sun. Soon, however, they will become more constant and will define my experience in the yard. I can’t rush this either. The bluebird will reveal itself when it is ready.

IT’S BEEN SEVERAL DAYS since the bluebirds arrived, and I have yet to see them. They continue to warble from somewhere high up. Although it is overcast, the day is bright to sensitive eyes accustomed to the dim winter light. I can see the yellow of the sun through the thin gray filter of clouds that keep the temperature no higher than fifty-two degrees.

The sun shines for an instant and burns through the shroud, and I notice shadows. They are short, and they keep mostly to the edge of the yard, where they’re lost among the raspberry shoots, canes, and fallen tree branches. A few shadows alongside the tallest trees extend out into bare lawn. A few weeks back, all the shadows were dramatic and contrasting, running out into the lawn and stretching all the way across, even at midday. Now the sun is much higher, the shadows shorter, and the wet pale lawn soaks up the sun’s energy.

The ground is no longer completely frozen. It’s now saturated with the fresh meltwater from last week’s snow. I step out into the backyard and am thrilled to be standing on soil and not knee-deep in snow. Before me, juncos chase one another from the white spruce and out into the open, while above, titmice fly from one side of the yard to the other, keeping to the woods that surround my yard. I hear a churring call from a red-bellied woodpecker, and through the woods, way back in the woodlot, a pair of crows fly deftly through the trees on their way toward the highway beyond. I see an empty pot that I left along the garden entrance on some warm autumn day. I find tomato stakes stacked up and leaning on the big white oak at the back of the garden. Memories of last season return as I step into the soft rich loam of my vegetable garden.

Last year I pruned back the butterfly bushes, and their growth accelerated. I’m cutting them back now with the hope of a similar result. The sun has just faded; all is shrouded again, one shadow covering all, and everything is bathed in evenly dim light. Then, just as quickly, before my hopes fail, it shines back again; now I even see some blue sky above. At this moment, a small shadow crosses the garden. A bird has just flown over me. Turning around to follow it, I see something blue on the pale lawn—a small piece of the sky fallen from the ether. Is it mine to keep? Can I walk over to it, pick it up off the lawn, and take it with me as a reminder of this early spring day? I’m walking toward it now and discover that it is a bluebird.

This encouraging drama plays out each year in my backyard, where for many years I’ve experienced the return of the bluebird in one remarkable way or another. This year, the bluebird has come back and brought with it the sky. Bluebirds have nested here for a total of nine years, during which time I’ve kept informal notes on their behavior. Last year, I awoke on March 14 to that familiar song and peered from my window to find a bluebird in the garden. It was a beautiful sight, as it always is. It flew over to the bluebird house and warbled a few inspiring, springlike notes. The bluebird had left by the time I’d finished breakfast, but it returned the next day.

The year before that, I sighted my first bluebird on March 21. I was making my way down the driveway and spotted it perched on the cable above. The next day, two bluebirds, a male and a female, were in the yard checking out the nest boxes. One year, a dark, almost indigo bluebird stayed and raised two broods with a fearless, practically tame female. I once went three years without any nesting; in fact, I saw not a single bluebird anywhere near Berry Lane in all that time.

I will never forget the first time a bluebird came into the yard here at Berry Lane. I was in the kitchen when the distinct flight of an unidentified bird caught my eye. I went to the window to get a better look, only to be baffled by what I saw. My unfamiliarity with the species combined with the distance of the bird made identification difficult. I knew immediately that it was a bluebird, however, when it flew to the birdhouse tacked onto the hickory. From the first moment I’d seen that tree, with the stones encircling it at the base, I knew that if I put a birdhouse there, a bluebird would someday nest in it. I don’t know if it was intuition or a premonition, but I do know that Berry Lane is not bluebird habitat. The entire neighborhood is shaded, and the only grassy space is about a quarter of a mile behind us, at Heather’s Meadow. I was nevertheless optimistically expecting bluebirds. Bluebirds are rather uncommon in the part of Massachusetts where I lived before I came to Berry Lane, so it was quite exciting to see those blue feathers against the freshly cut wood of the birdhouse for the first time.

Bluebirds are popular among the general public. I always get plenty of responses from my readers whenever I write about them in my column. Popular culture has always associated the bird with happiness, and I can’t say I disagree with this assessment. I have pleasant memories of being with Heather in the backyard while the bluebirds went about their business. She and I would watch them fly to and from the nest box to unknown pastures. At other times, the male would rise up to the clothesline that runs across the yard, perch for some time, and then drop down to the ground for an insect snack. Often, the bluebirds would fly out to the garden and perch on my tomato stakes, where we could see them catch pests and take them back with them to the nest box. I would often instruct Heather to find a worm to bring to them. Today she wouldn’t touch a worm for all the money in the world, but back when she was just a toddler, she was bold, fearless in every way, ready to conquer her world, and she placed earthworms on an exposed rock a few feet from the nest box. She would then run back into my arms, and we’d wait for the bluebird to fly down for the worm. This, of course, always worked better with a little encouragement from Heather in the form of an ebullient greeting. “Hello, Mr. Bluebird, hello!” Then, as if on cue, Mr. Bluebird would fly down and make off with the rich offering. It never failed.

Heather has recently begun to ask me a lot of bluebird-related questions. Yesterday, she wanted to know why there were not more of them. I explained that the harsh winters of our area make it difficult for bluebirds to survive here. I mentioned our recent heavy snowfall and I reminded her of the bitterly cold winter we had here ten years ago, when even the South was plagued by freezing temperatures. I told her how Atlanta had received a few inches of snow in March, while southern Florida approached the freezing point as far south as Fort Myers. I said that these are deadly temperatures for the eastern bluebird; even the hardiest among the species can’t tolerate them for long.

This all got me thinking about the many ways bluebirds survive our long winters. I know they endure the harsh New England winter nights crowded together in nest boxes and tree cavities. I also know that, by feeding on fruit and frequenting warmer locations such as along the coast, bluebirds somehow manage to make it. Unfortunately, their sensitivity to cold is just one of many factors that keep bluebird populations low in New England.

Bluebirds also face competition from other birds that dominate their nesting cavities. Many people have witnessed firsthand the familiar battle between the native bluebird and the exotic English sparrow. Though bluebirds are determined in their efforts, they are eventually thwarted, and the nest box or tree cavity becomes home to the ever-abundant sparrow. The house wren will compete for their nest boxes, too.

Before these exotic English sparrows were brought to North America in 1851, bluebirds were more common in the East than they are today, even abundant in some places. It was a time when much of the country was clear and open, when fence posts were made of wood, and dead trees were left standing along the endless hedgerows. The open agricultural land created habitat, while the fence posts and dead trees provided nesting cavities. Advancements in plowing technology eventually opened the American West to farming, so farmers in the East abandoned their lands for better soils. The fields underwent succession and eventually turned back into forested land. Wildlife that had been nearly driven to extinction in the East by the previous deforestation began to return, but a few select species (like the bluebird) lost their required open-pasture habitat. In the 1800s the East was 75 percent cleared, while today it is 80 percent wooded—a complete reversal.

Fortunately, bluebird numbers increased from critically low or threatened status with the help of several concerned people. In 1926, Thomas E. Musselman established the first local bluebird nest box trail. Later, in 1938, Mrs. Oscar Findley’s local junior Audubon club of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, sparked the creation of the National Bluebird Trail. Soon other grassroots efforts started. A garden club secured permission from the Missouri Department of Transportation to place nesting boxes along state highways, for example. The cause really took off with the creation of the North American Bluebird Society in 1978 and the bluebird-restoration campaign of Dr. Lawrence Zeleny, who popularized the placement of nest boxes on private land.

More recently, we’ve seen the creation of the Connecticut Bluebird Restoration Project, a private nonprofit organization dedicated to the restoration, conservation, and management of native cavity-nesting birds that monitors up to twenty-five hundred nest boxes. The project is centered at the White Memorial Conservation Center in nearby Litchfield, Connecticut. Although bluebird habitat remains scarce in my county, vast acreages of suitable habitat have gone unrecognized here in town. Public school yards, parks, farmland, and private bucolic settings of one kind or another all provide habitat, but what we need are the nesting boxes.

Nesting cavities are in such demand that bluebirds will often nest in less-than-desirable places if a box is available to them. The pair that nests in my backyard proves this because my yard is far from the pastoral open country habitat they prefer. My bluebirds do what I have done for years—they commute. They fly to Heather’s Meadow to feed on the abundant insect life thriving there. I also have a rich supply of pests, and the birds have found that they can do fairly well right where they are. As a result, they spend about two-thirds of their time in my insect-infested backyard. After all, how could a bird lover such as myself indiscriminately spray insecticides over everything? I certainly don’t want to do anything to harm these birds because something about them captivates me. I can’t quite figure out what it is about their presence, but they definitely add character to the yard. Perhaps it is their tame dispositions or just their brilliant blue plumage. Whatever it is, I am always happy to see them again.

I’m on the driveway walking back from the mailbox; off in the distance, I hear a familiar birdsong. It sounds like cheerily, cheery, cheery. I stop in my tracks and realize that it is a robin. Today is March 28. I have waited for this moment since the hot, dry afternoon of August 20, which was the last time I heard a robin singing. I listen carefully and appreciatively, and take in each phrase of the song. Before me I can see Berry Lane with its towering oaks, scattered homes, and melancholy sky. The sun is sinking behind the distant line of trees, trembling like a mirage and fluctuating in vapor until it breaks into pieces of golden light that slowly slip away, leaving a clear sky above that soon darkens to a purple dusk. Standing here for a long time until the deep dusk settles in, I can now hear another robin singing from way down on Fern Drive. With that, the season of song begins here on Berry Lane.

I am enthralled: I can now see the first faint hint of a star appear in the southern sky. At this precise moment, the light intensity fades enough to prompt the singing to come to a climax and then stop. March will be coming to an end. The robins are back on the lawns, woodcocks are in the soggy meadows, the fresh scent of the thawing earth is rising quickly. Soon it will be April.