SEPTEMBER

Silent Sunrise

I HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY to observe my window feeder for an entire morning. From the moment the first rays of sunlight emerge, I can see every bird that comes to feed. Because I’ve been doing some painting, cleaning, and moving, I found myself rolling out the sleeping bag in the living room to escape the fumes and chaos in the bedroom. Although I would prefer a night on a comfortable mattress in the bedroom, I know that a night beneath the picture window in the living room can give me a front-row seat from which to view the window feeder come morning.

It all begins before sunrise with a tenacious little Carolina wren. Long before the other birds are stirring, this curious wren defies the darkness and wakes me with gentle taps upon the sill. Buried beneath my down wrappings, I peer out with heavy eyelids toward the window, where I spy the wren.

It is apparently devouring the spider eggs suspended against the glass. I’m astonished at first, not accustomed to greeting the day in such an unusual way, but soon the peace and warmth of my slumber beckon me back into my downy shell. Wanting to sleep more, I soon become annoyed by my little friend’s window tapping. Eventually, he flies off and is heard ringing out from the raspberry tangles way out back.

For the next hour, I remain semi-alert while drifting in and out of a dreamy slumber. A dim silvery light reveals the vague shape of trees, and I know that the day will soon begin. A crow starts sounding off somewhere, and then tufted titmice begin calling to each other. How I love to listen to the birds in the early morning, even if they are not singing and just calling out to each other. Soon, the sun adds golden hues to the trees, but I still can’t be coaxed from my warm sleeping bag. Perhaps I should have toted a space heater nearby before retiring for the night because this would have made getting up easier.

It doesn’t matter now, though. My peace has just been broken; an aggressive blue jay lands, screaming in bold defiance with its crest raised and beak open. Its cries give all a sense of urgency, and I’m now up for the day. The blue jay is telling every living thing within earshot that it has arrived, and the fresh offerings of seed and suet belong to it and other blue jays only.

Soon, the blue jay’s comrades arrive to join the crested glutton. I look up, and in the trees all around the jay are other jays cleverly planning their ascent upon it as it feeds alone, breast-deep in seed. I look straight into its eyes and can see the burning intellect of this species, which is so well documented.

After the jays thrash about and spill seed everywhere on the ground for the squirrels to eat, other birds begin to fly up to the window. The majority of them are tufted titmice, but I see many woodpeckers, too. The first, a drab downy woodpecker, doesn’t stay for long. A nervous individual, this bird flies in and then leaves with just one seed. Its close cousin, the larger hairy woodpecker, remains for longer, nearly making quick work of the suet cake in one visit. Still larger is a red-bellied woodpecker that flashes its vibrant colors.

With the progression of the morning, I witness a wide variety of species. There are the usual suspects, such as white-breasted nuthatches, chickadees, chipping sparrows, goldfinches, house finches, and cardinals. Perhaps the most beautiful is the yellow-rumped warbler that has just landed on the suet. I watch it flit about and then depart without feeding.

The clock says noon, and I’ve just finished some work in the living room, so I sit down for lunch at the kitchen table, from which I still have a view of the feeder. I tell myself that I’ll be out of the house in just a minute and remember that I need to stop at the feed store for more seed while on my way through town. I can’t imagine spending this time indoors without the enjoyment of nature at my window. Should I put a window feeder on the bedroom sill or will the wren supplant my alarm clock?

I’M BACK IN MY BEDROOM NOW that the painting is complete. It will feel good to sleep in my bed again. It took two weeks to paint the walls and move all the furniture back in place. I’ve been so busy that I couldn’t find time to paint the room all at once. I guess September will fly by, just as August did. I honestly don’t know where the time goes, but I believe that I’m taking advantage of good health and making the most of each day.

September seems to be the forgotten month—overlooked and underappreciated. It is as if there is an organized rush to prematurely declare the summer over. We all enjoy the county fairs, hot chocolate, pumpkins, fall colors, and cool crisp temperatures. Yet September does its best to maintain some warmth for us. There are a few nice days left, and those bright blue skies just can’t be beat. But the warm days seem to go unnoticed in the excited anticipation of fall. I put the blame on Labor Day, which is seen as the official end to summer. Why make haste of a great season? Summer doesn’t end until the fall equinox.

September is the month of transition. It is the time when most birds are through with breeding and begin preparing for migration. They take to sulking in hedgerows and high canopy branches. Still present, they quietly await the long journey back to the south. Others, such as herons, shorebirds, and wood warblers, have already started to migrate. Those mornings filled with song are now long gone. In fact, I have not heard a robin sing since August 27, and it has been getting quieter each morning since then. At dusk, however, my resident wood thrush continues his nervous alarm calls while he chooses his roost. He will wait for the intensity of the light to fade with the setting autumn sun, and when the timing is right, he will take to the sky, heading south.

I have been paying close attention to the hummingbirds, which are often scarce by now. My thought is that they are gaining some strength before migration and finding an efficient intake of calories at the easy nectar feeder, which must be easier than searching for the last remaining blossoms. If you think about it, the feeder eliminates the expenditure of energy on flying from flower to flower or garden to garden. After all, it is all about calories consumed versus calories expended.

The truth, I have learned, is that these tiny birds can’t actually fuel up for migration until immediately before departing. In fact, their calorie needs are so high that whatever fat they have stored is usually expended before the next morning. In other words, they can store only enough reserves to make it through the night. But then their system changes drastically in response to the shorter summer days. They begin to feel the urge to migrate as they sense the summer light fading, and metabolic changes now allow them to store more fat. In the last days before migration, hummingbirds really pack on the weight.

They go from an average weight of three grams to roughly four and a half grams, gaining anywhere from one to 13 percent of their body weight each day. In just a few days, their rotund appearance indicates their readiness to begin their long journey. Their excess fat or energy reserves will be needed to maintain their flight speeds, which average between twenty-five and fifty miles per hour. Most, but not all, hummingbirds make the return, crossing over the Gulf of Mexico, and this nonstop flight takes about eighteen to twenty hours. Approximately, one and a half grams of fat will fuel the bird, enabling it to cover the six-hundred-mile trip, sometimes with energy to spare.

So there is no fattening up or fueling up in preparation for migration until the days get considerably shorter, as they will soon. It seems hummingbirds are prime examples of efficiency—a supreme design via the forces of evolution. What we see today is this perfection gained over time, but efficiency seems to keep them living on the edge. They are just hours away from depleting their energy at any given moment, living on the brink of starvation each summer day, with only enough fat reserves to survive one night. This doesn’t give them much of a safety margin. What happens, you might wonder, if food is hard to find or the weather becomes unfavorable for feeding? This is a real possibility, especially in late summer. Although I have never seen a hummingbird in such a state, I’m told they go into what scientists call torpor, which allows them to endure this unexpected situation. Apparently, it isn’t unique to hummingbirds, but they are the only birds that can achieve this state on a daily basis as needed. This short-term or overnight torpor may also be known as noctivation. It is basically like hibernation, except that it is not prolonged or seasonal. Hummingbirds use this strategy at any time of year to survive cold nights and severe weather conditions when feeding is nearly impossible. Torpor slows their metabolism by as much as 95 percent, thereby reducing their energy demands by 50 percent. During torpor, their body temperature slips dangerously low, to the point just before hypothermia. This is referred to as the set point, and the hummingbird’s internal thermostat makes adjustments so that the bird’s body temperature never falls below this point. But the way I see it, the bird is basically at death’s door during torpor.

In this state, hummingbirds are unresponsive and therefore extremely vulnerable if discovered, which is why they choose their overnight roosts or torpor sites very carefully. Two hours before sunrise, the hummingbird’s internal circadian rhythm prompts the awakening process. It takes the hummingbird twenty minutes to come out of torpor. This is achieved by shivering or by vibrating the wings in place. Slowly, the bird is sufficiently warmed to engage in feeding, and its energy is restored.

All of this is fascinating to me. I think about these details as I watch the hummingbirds buzz about the yard. They have gotten away from the garden now and have begun to visit the feeder full of red nectar that is hanging on the deck. I can’t say exactly when they will depart, but there will soon be a day, about the middle of September, when their presence will be missed. You always know when they depart. You just realize one day that you haven’t seen any for a day or two, and then you know that they have left. I keep my feeder hanging, though, because sometimes there is a straggler or two.

It is different when it comes to other birds. It takes longer to recognize that they are absent. Take catbirds, for example: you just don’t hear them too often in late summer, so it’s difficult to know exactly when they leave. It just hits you one day; you realize that you haven’t seen this bird or that bird for a few days. Sometimes, I deliberately walk the woodlot, looking for summer songbirds. Surprisingly, I still find a few of them about, living unobtrusively in the wetland.

TODAY WAS ONE OF THOSE classic days—clear, clean, and rich with an earthy early-autumn smell. Now, the moon appears nearly full and will soon shine bright like a beacon. Heather and I are talking about how quickly the summer sounds have faded. Tonight, we hear the katydids stridulating loud and clear, and we wonder if there will be another warm spell. I believe there will be, but it will not make the birds sing. Tomorrow, the sun will rise in silence, except for the distant chatter of the jays.

So I listen to the blue jays now. I listen no matter what I am doing. I can hear them inside, even with the windows closed. I listen to what they are doing. I listen to each call, each rattle, and each song note. They have plenty of calls, and I am learning every one of them. I am learning what they mean, and they tell me what the blue jays are doing.

Ruby-throated Hummingbird

I can count on the jays to greet the rising sun. While other birds have been silent, the blue jays have continued their antics as usual. September is their month. They now stand out, as conspicuous as they are loud and boisterous. Their blue plumage contrasts against the fading green, the hint of gold, and the yellow, forming a kaleidoscope of early fall colors.

Yet even the reliable blue jay must make some adjustments with the changing season. The very same individual blue jays that departed last spring will return to my feeders this year to once again take advantage of the generous bounty. Many blue jays join large flocks and fly south, but some will stay local, remaining nearby throughout the entire year. The order of things is complicated when it comes to blue jays and fall migration.

Ironically, unless birders themselves band the blue jays at their feeders with identification markers, they simply can’t recognize which jays have stayed for another winter and which have recently arrived from the north. Birders therefore come to believe that the same individual blue jays are present year-round.

In fact, many people believe that blue jays are nonmigratory, but just witness their huge flocks moving over the countryside, and all doubt about their nonmigratory nature fades away forever. Birders frequently report flocks of tens of thousands in the Midwest. While we don’t know much about blue jay migration or their seasonal shifts, we do know that their movements fluctuate yearly and are probably motivated by the availability of food sources. Ornithologists don’t know yet which blue jays decide to go here or there. Some believe that younger blue jays, inexperienced at winter survival, depart to improve their chances of finding food. To my knowledge, however, the research is inconclusive.

I know of a blue jay that never migrated anywhere. This particular blue jay had a steady source of food without ever making a seasonal shift. She lived at nearby Hammonasset State Park and made her home inside the Meigs Point Nature Center. The fledgling jay fell from its nest and was taken in by well-meaning humans. This was the wrong decision; they should have placed the bird on a tree limb for its parents to find. They kept the bird for many years until finally handing her over to a rehabilitator, who then brought her to the nature center. The bird could not be rehabilitated back into the wild because she had already imprinted on humans. The jay, known as Cutie, stole the hearts of everyone with her remarkable personality. Cutie liked to hide objects on her caretakers and mimic fire alarms and cell phones. She was especially fond of children. Jays are like that. They leave you guessing about what they might do next.

Perhaps this is why blue jays are so fascinating to watch. Whether the jays in this neighborhood leave, stay, or return, rest assured that there will be at least a few of them to take advantage of my feeder. At this time, when other birds are silent, I count on the blue jays to startle the morning air with raucous alarm in the smoky-gold autumn mist.

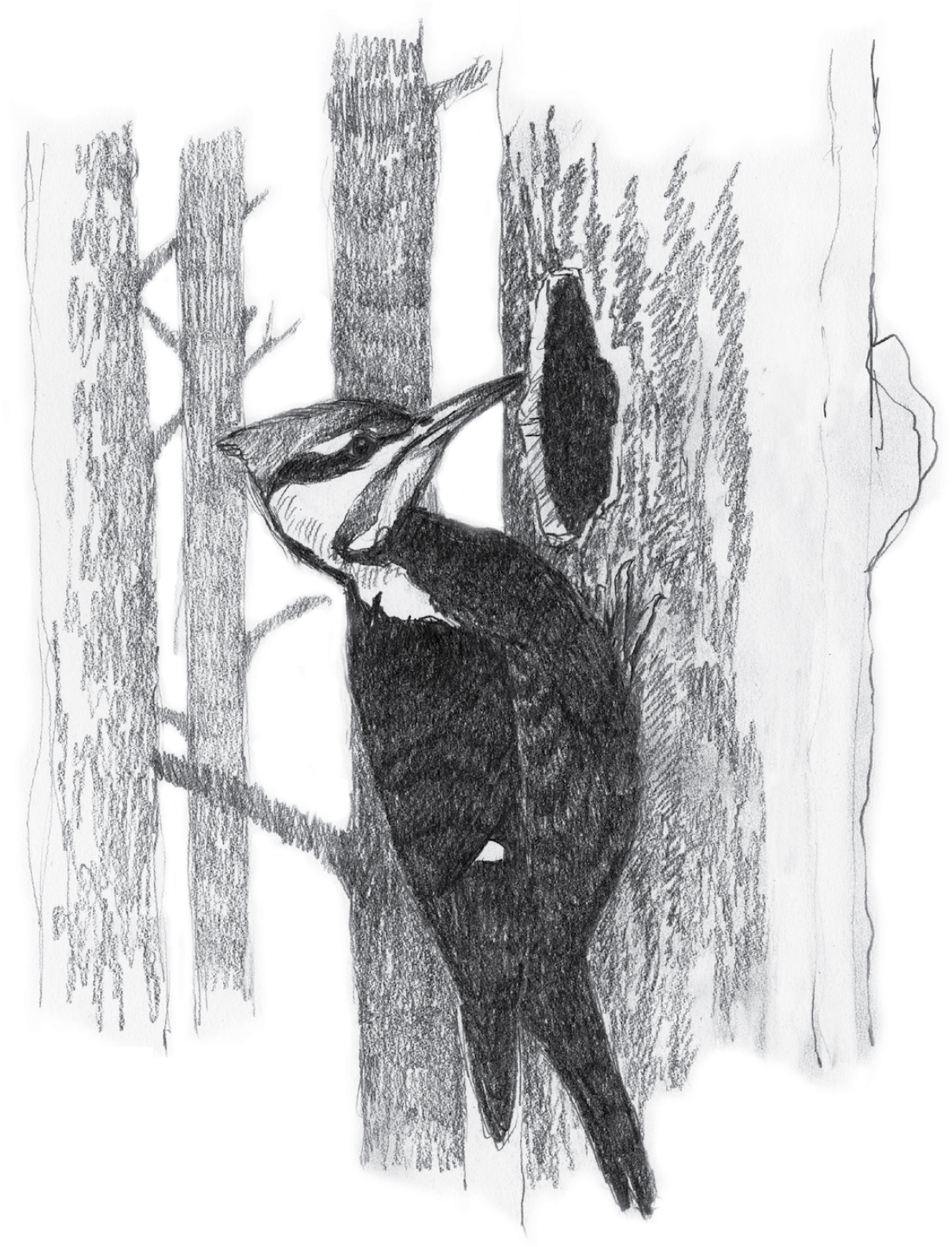

WOODPECKERS ARE ABUNDANT yearlong in my back woodlot; I regularly see both the downy and hairy varieties. Occasionally, I’m surprised by a colorful northern flicker, and there are always a few red-bellied woodpeckers at the suet feeder. While each of these birds can give forth some loud call notes, nothing could have prepared me for the tin-horn blasting that I received yesterday morning at sunrise. I stepped out onto the deck to investigate, and there it was—a giant red-and-black pileated woodpecker.

The sight of this majestic crow-sized bird dazzled me as I stood there in the early dawn. The large beak, midnight-black wings, white stripes down the neck, and flashings of pure red adorned the impressive frame of the largest woodpecker known in the Northeast. He worked the trunk of my old black oak carefully, let out a startling call, and flew to another massive oak a little further back from the house.

I lost sight of him at times as he slipped from view, momentarily going behind leaves. He then reappeared in full view for yet another encore, working his way around and around the girth of the oak. Impulsively, he made another tin-trumpet call, and off he flew back over the yard, up and away, out of sight, and gone. I have heard his trumpet many times since but have never seen him again. The pileated woodpecker has a huge territory of anywhere from one thousand to three thousand acres, according to some studies. It has a distinct affinity for the wild, is extremely wary and shy, and is very elusive during the breeding season. It requires a mature forest with large trees and plenty of dead standing tree snags. My guess is that his mate had a nest somewhere in the nearby Babcock Wildlife Management Area or the Salmon River State Forest. From his lofty view, he can find and descend on smaller pieces of land, such as mine. Deeper in the larger woodland preserves, this male bird probably helped its mate incubate one to six eggs and feed the young. They remain vigilant parents until September, when the offspring are finally independent. Pileated woodpeckers eat carpenter ants and drill large, deep holes, which other creatures utilize.

Pileated Woodpecker

This encounter was my first here at the house, though I see pileated woodpeckers frequently in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. There, where the wood thrush sings from the ferns and the lazy notes of the warbler float through the silent forests, the jolting horn-blast of the pileated woodpecker can cause your blood to freeze in your veins. Whether we see more of this bird in the future, as trees mature and forests age, depends on the preservation of older growth woodlands. Today, professional forestry recognizes this as significant, and I hope it is a continuing trend.

SEPTEMBER IS HAWK MIGRATION time, and diehard hawk watchers will be out in full force counting hawks this weekend. The nature of hawk migration, which occurs during daylight and is readily visible in the sky, allows for a perfect opportunity to inventory these magnificent birds of prey. Keeping abreast of the trends and fluctuations in their numbers is good for hawk conservation.

Besides my resident red-shouldered hawks and the occasional sharp-shinned hawk, there are not many in my immediate neighborhood. There are dozens of red-tailed hawks along the highway but not in my woodlot. When I do see other kinds of hawks, it is generally around this time of year, and they are so far up in the sky that it makes discerning their identity nearly impossible.

The identification of hawks is challenging because of the distance from which they are often observed. Although they are sometimes found perched on a limb or floating silently above a wooded trail, their wary nature never allows us more than a moment’s worth of observation. Whether it is the factor of time or distance, hawks rarely give us any margin for error. Instead, birders must be prepared before they venture afield. I have learned and committed to memory the significant differences between wide-winged buteos, slender accipiters, falcons, large vultures, and eagles, thereby making quick glimpses sufficient for me to know which birds I am seeing. Over time, sightings that may have been otherwise frustrating have become rewarding.

Of the group known as the buteos, the broad-winged hawk is discussed most often. This is the hawk that so many claim to see from lofty peaks and precarious ridges during hawk migration. Along these escarpments, the birds catch the rising air, or thermals. Broad-winged hawks, like other hawks, hitch a lift from the thermals and soar for miles. They can be distinguished from other hawks by their short wings, fanned tails, and short stocky bodies. Their stocky build contrasts with that of the large, lanky, rough-legged hawk. I never encounter these birds in the same habitat, but they can be seen together during migration. The length of the wings is all that is needed to distinguish between the two varieties: the rough-legged hawk has much longer wings. Its dark contrasting plumage is also noticeable from the ground at great distances.

Red-tailed hawks often confuse birders who are expecting to see red tails. The red tail is not usually visible and, when it is seen, it is more likely to appear rufous. Much of the time, this hawk is identified by its dull-colored body and large size. The red-tailed hawks’ hunting habits are somewhat like those of the American kestrels, and they are known to hang in the air for many moments.

The red-shouldered hawk can be distinguished by its behavior, which is more hyperactive than that of the other buteos. During hawk watches, the red-shouldered hawk can be distinguished from others by the crescent patch on the end of its wing. Living with these hawks at close range has made identification easy for me.

People living on and around Berry Lane ask me about three accipiters. (These are hawks with short rounded wings and long rudder-like tails.) Two of them—the Cooper’s and the sharp-shinned—are nearly indistinguishable unless you are aware of the minor differences between them. The Cooper’s hawk is a bit larger—about the size of a crow—and has a lanky look to its wings, which are longer than those of the sharp-shinned. The head of the Cooper’s is also larger, and the tail is rounded at the end. The sharp-shinned hawk is pigeon-sized and has a long, narrow tail and a small body. Some of my birder friends mistake it for an American kestrel, which is also small and long-tailed. However, the kestrel is really a falcon, and its angular wings make a distinct flight pattern.

The third accipiter found in the New England region—but rarely seen near Berry Lane—is the northern goshawk. Its plumage is not identical to that of the sharp-shinned and Cooper’s hawks. Rather, the northern goshawk has a wide tail that is covered with contrasting heavy banding. It also has a great deal of streaking on the breast and a faster wing beat than the Cooper’s hawk. Northern goshawks are significantly larger than sharp-shinned and Cooper’s hawks.

This weekend, I will probably do my hawk watching along the coast because it is closer than any of the well-known hawk-viewing summits. I think watching hawks along the coast is more challenging because it is the route that atypically marked juvenile hawks follow. Only experienced hawks are able to learn the migration routes that follow the mountain ridges. Juveniles can follow the coastline more easily and can work their way south without much confusion.

I AM CUTTING BACK THE BRUSH near the shed, and I can see a group of chickadee-sized birds flitting about the branches down near the wetland. I am walking there now, making my way down the tiny embankment and into the woodlot. I can’t tell just yet, but I don’t think these are chickadees. For one thing, I don’t hear the typical chickadee call notes. These birds are silent.

I witness one of these birds fly out into plain view. I am now certain that they are not chickadees. Could they be kinglets? The stripe on the head of one bird makes me think these could be golden-crowned kinglets. Their small sizes and ample bodies are further evidence. There are five of them—one at ground level, two on branches about mid-canopy, and two more deeper in the woodlot at around five feet above the ground. The closer I get to them, the further they retreat.

These woods are full of small sticks that crack and snap with every step. I am wondering if I will ever get close enough to know just what the birds are. I decide to wait, standing motionless and hoping that they will make their way back toward me. They are at the edge of the wetland, where there is little understory. I think they will have to come back this way to forage where there are saplings and native shrubs.

I rack my brain for guidance and bring up mental images of various species of wood warblers. I now wonder, Could these be warblers? My confusion would make sense if these were juvenile warblers. Juveniles are notoriously difficult to identify because of their often atypically marked and colored plumage. Yet the birds in front of me are not juveniles. These mature birds appear similar to each other and have distinct plumage, which I should be able to identify if I get closer.

I give up waiting and make my way through the maple-leaved viburnum, over the sticks, and to within thirty feet of the mystery birds. They don’t retreat but instead come closer as if to investigate my presence nonchalantly while foraging at an energetic pace. At last, they are close enough for me to discern their plumage coloration.

The black crown stripe and thin black line through the eye identify these birds as worm-eating warblers. I have seen them here many years ago. I have never seen one during the breeding season; however, my woodlot could possibly entice one to establish a territory and raise young. It has some of the bird’s habitat requirements; the trees are mature, and the understory is dense in some places. If there are any breeding locally, I think they would be twenty miles southeast of here, where there are several hundred acres of huge oaks growing on steep, rocky hills covered with dense stands of mountain laurel. That is a more suitable place for them than my woodlot.

Worm-eating warblers prefer large, undisturbed tracts of deciduous or mixed woodlands. Like so many species, this warbler has been pushing its range farther north. At present, worm-eating warblers can be found as far north as southern Vermont. There is a stronghold of these birds in Massachusetts, especially in the Berkshire Hills, Central Massachusetts, and along the Connecticut River Valley. I’m sure they are expanding north in other parts of the United States, too.

TODAY IS THE FIRST DAY OF AUTUMN. Acorns are dropping from the heights of our great oaks. When they hit my neighbor Lilly’s metal shed, they sound like rifle fire. It isn’t hunting season yet, but it sure sounds like it. Fortunately, for the sake of my sanity, it isn’t a good year for acorns. It is a low crop this year, which means a harder winter for deer and turkey.

Acorns can do a lot of damage to prized possessions, such as outdoor grill tops and parked cars. So my neighbor Dave has his antique ’68 Cougar parked safely in my garage. It’s a nice arrangement for both of us. I help him keep his pride and joy in pristine condition, and in turn he clears my driveway each winter. He came over today, in fact, to peek through the garage window at his baby. He told me he appreciated having the car inside, away from the falling “coconuts,” as he calls them. “Coconut” season it is, once again.

I have always wanted to make good use of the acorn bounty. When things were getting tough during the recession of 2008, I often joked with people about how I would survive by eating squirrels and acorns should the economy tank out into a full depression. When Heather was little, we looked into making pancakes from acorns. We found an old book about Native Americans and learned how they did it. We spent an entire afternoon competing with squirrels, gathering up their best nuts. By dinnertime, we had a grocery bag full of them, but the day of reckoning never came because Heather lost interest. We hid them in my shed, and they sat in there for weeks until the squirrels got to them and made a mess. From what I have heard, acorns don’t taste good, but I am still curious. Fresh tomatoes, in contrast, do taste good. In fact, there are few things as good as a fresh garden tomato with a little black pepper. I have dozens of tomatoes now. They were well worth waiting for.

Soon, the fall migration will be over; eventually, the nuthatches, titmice, and downy woodpeckers will follow the chickadees to form their winter flocks. Juncos and white-throated sparrows will arrive, too. For now, I am going to search for those sulking songbirds, chase after late shorebirds, watch hawks, and otherwise enjoy the beautiful, clear, crisp days of September.