OCTOBER

Old Sam Peabody

THE LOW LIGHT OF OCTOBER has a unique quality, with its long shadows and filtered hues. October’s sunlight is enhanced by the emerging colors of the autumn foliage; with this diffused light comes a feeling of excitement that’s special to the season. The birds feel it, too, for their lives are dictated by the sun and the softening of the changing light.

While I prepare mentally for the end of daylight saving time and the plunge into early darkness at day’s end later in the season, the birds know only of the equinox or celestial movement and not the turning of clocks and watches and computers. The days will shorten independently of our clocks, and the earth, from where I stand now on Berry Lane, will slowly tilt farther from the warmth of the sun each day. And so, even though the temperature is in the upper seventies, I can scarcely find a ray of sunlight on the deck. I look up and see that the sun has barely made it over the oak by my bedroom window. It’s incredibly low: so low that even at high noon it can’t quite crest the trees.

Today, only a few trees here and there have begun to change colors. Along the highway, I noticed that the birches have gone from faded green to a subdued yellow. In fact, the only color change now is yellow. While the green leaves still prevail and yellow slowly advances, the lawns grow richer with the coolness of the season. Fully recovered now from the scorching August sun and drought, they’re deep green everywhere I look. Even the more poorly kept lawns are deeply verdant. Mine is no exception, but I hesitate to call it a real lawn—instead, my backyard is a mixture of weeds, wildflowers, and crabgrass. Cutting it gives it the appearance of a real lawn, but the lawn has very little actual grass. The front yard’s even worse; it doesn’t receive much direct sunlight, and the soil is compact. I’ve never had luck growing a nice lawn there, so I decided to give up trying to grow grass and instead let shade-loving perennials take over the entire area.

I figured I would give myself two hours this morning to begin transforming the tired lawn into the new shade garden. Two hours should be plenty of time to get it looking a little better and to enjoy some outdoor time on this warm autumn day. I spent much of this time searching for the base leaves of the daisies that grew in thick profusion in July. They were easy to distinguish from the other plants and grasses. Most of the daisies grew near the old wooden swing set in the backyard and were easy for me to dig up in the barren parts of the lawn where grass never gained a stronghold beneath the feet of playing children. I used a hoe to scrape them up and transplant them to the front yard, where I’d already removed the sod. Once I was satisfied with the dozen or so daisies I’d transplanted, I dug a deep hole and carefully settled a butterfly bush root-bundle inside it. This marks the beginning of my small naturalized garden—a little something different to replace the patchy grass and add some color and character to the front yard. After all, how many people actually see my garden in the back?

I might have accomplished more had I not been looking at the warblers. They appeared in one small band—a noisy little group that seemed to appear from nowhere and was full of different species. A single warbler caught my attention this time. It flitted about all alone on the branches of the yellow birch growing alongside the house. It had an eye ring and two distinct white wing bars, but I couldn’t determine the species.

Although notoriously difficult to identify, fall wood warblers are a conquerable challenge. The main difficulty is generally thought to be a result of molting. This is a myth, however, because wood warblers begin to molt immediately after breeding. Instead, it is the juveniles that create the problem in identifying fall warblers because most of the adult warblers have already passed through our region in late summer. The warblers that create the most problems in identification are specifically the pine, blackpoll, black-and-white, bay-breasted, magnolia, and yellow-rumped warblers.

The little band of birds eventually moved on, and the yard became quiet. I raked all the leaves from beneath the spruce trees in the front yard and pushed them into the woods near the fly-through feeder. Seven or so nuthatches swooped in, one after another, taking turns and grabbing seeds before exiting the feeder. I looked up in the trees near the feeder and saw that the large red oaks seemed to be covered with them.

It’s high noon now, and it seems my time out in the yard this morning has been more productive in warbler watching than in leaf raking. I’d better get back inside so I can finish my column and get it out to the newspaper before it gets too late.

IT’S EARLY EVENING, the column has been sent off, and I can see golden hues appearing in the west. I’m back to my raking in time to see my resident cardinal. Like clockwork, the brilliant-red male cardinal returns to roost every evening at exactly twenty minutes after the sun has set. I can hear his nervous notes as he approaches from somewhere in the neighborhood. His calls grow louder as he flies closer to the rhododendron beneath my living room window, where he settles in for the night after a few adjustments to find a finer and safer perch. His call notes stop once he finds his perfect place: a thin but stable limb close to the house that offers a view of everything nearby.

One might wonder why he would choose to roost so close to the house. After all, a wild bird ought to find security farther away from such a busy place as my front yard. Though I’ve accidentally flushed the bird on many occasions when I’ve returned home late at night, the rhododendron has its advantages for the cardinal. For starters, the rhododendron keeps its leaves in the winter and therefore helps to offer shelter from heavy snowfall. The rhododendron is also near the fly-through feeder. The roost faces southwest, meaning that the house acts as a windbreak from the cold north side of the house. It’s also generally a few degrees warmer next to houses because heat inevitably escapes from the interior of any home. Finally, few predators such as hawks and owls are likely to venture so close to a human dwelling. Looking at the cardinal’s choice this way, it makes good sense to roost in my rhododendron. It makes for a very warm and safe place to spend the night.

Different species have different roosting preferences. Some roost in large flocks and some in pairs, while others choose to roost alone for part of the year and in flocks at other times. These differences represent specific strategies that help each species survive. Birds that roost in a huddle obviously benefit from one another’s body heat, but a pair that roosts together may have other reasons for sharing the night. Pairs often roost together prior to nesting as a way of cementing their relationship in anticipation of the rigors of caring jointly for their young. In some cases, a female will roost closely with her mate in order to keep him from wandering or having relations with another female.

Communal roosts are strategic for several reasons. Large flocks that come together at dusk may have a better chance of spotting approaching predators with a collective set of many eyes; these birds may also be sharing information about where food is available. This way, younger, less experienced birds may follow the older birds to food sources when they begin to forage at daybreak.

For my cardinal, foraging begins at daybreak, before the sun’s fully illuminated my field of vision. The day begins as it ended, with the cardinal’s call notes; when the last star flickers and fades into the increasing light, he ventures to the feeder and then far beyond into the neighborhood. The cardinal survives another day.

IT’S A COLD AUTUMN DAY, and Heather and I are hanging out together with Zoey and Stripe. I decide to stand in front of the living room window and watch a group of jays dominate the fly-through feeder. What is a jay if not bold and brilliantly blue? One hammers away at a sunflower seed tightly held between its feet while another devours them whole, repeatedly cocking its head back to swallow the seeds; the others grab the seeds and leave.

I’m waiting for something to startle them into leaving, but nothing does. I wait some more. I tell Heather about the jays while she goes about her chores in the house. I’m still peering out the window when I hear a lisping call note. I listen and hear it again. It’s coming from beneath the window. I look down into the rhododendron and there it is. I tell Heather that they’re here—the “winter sparrows” are here! A single white-throated sparrow perches below me in the bush and lets out a distinct series of call notes. Soon the yard is filled with sparrows.

It almost appears as if the soil is moving. These little brown sparrows are hopping all over the ground, and I can see a concentration of them directly beneath the feeder. I strain my eyes and spot more of them beneath the small spruce that define the boundary between Dave’s yard and mine. I can see their white-and-black head stripes, but otherwise they blend in, camouflaged by their surroundings.

White-throated sparrows do not typically breed in Connecticut. I’ve never seen or heard them in my yard or woods during the breeding season. They are abundant to the north, though, in northern Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, and even farther to the north in Canada. White-throated sparrows begin their journey south just about the time when the first snowflakes are beginning to fly and the leaves have all fallen in these northerly regions. I eagerly await their arrival every year.

Their song is so sweet that once you hear it, it stays with you. Many people say that it isn’t possible to hear this fine music in the crisp fall air—only in spring and summer—yet I’ve sometimes heard it coming from the morning mist and the hidden corners of the dusk in fall. It stops me in my tracks each time, and I imagine their breeding range, where the spruce forests seem endless and the meandering trout streams seep into unnamed moose bogs. There they sing clearly, with a wavering plaintive melody. You can hear them everywhere in good conifer forest-edge habitat, but white-throated sparrows are rather secretive within their breeding range. They stay hidden in the willows and spruce that line the wetlands, streams, meadows, and ponds where they nest.

They come from places such as Indian Stream, along the headwaters of the Connecticut River within the Connecticut Lakes region, and east of there, behind the Magalloway River, to the far north beyond the logging roads of Jackman, Maine, and the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. In these woods, the brown-backed, white-and-black-crowned bird sings forever into the summer night. It sings for a real popular fellow, so the locals say, whose name can be heard across the north country. The little sparrow calls the name out with respect, delicately faint and slightly sad in tune: Old Sam Peabody, old Sam Peabody! Sometimes it sounds like this: Old Sam Peabody, Peabody, Peabody, Peabody. In Canada, if you ask, Canadians will deny this; they’ll say there’s no one named Peabody in these woods. After all, if he existed, wouldn’t he answer the little bird? They say proudly the bird is singing, O Canada, Canada, Canada.

The female builds a nest made of grass, fine rootlets, and sometimes deer hair on or close to the ground and lays between one and six eggs. Concealed on all but one side, the nest allows her to incubate her lilac-colored eggs for two weeks.

White-throated sparrows become more conspicuous after the breeding season. Here in Connecticut, as is the case elsewhere in the winter, white-throated sparrows often seem to get flushed out from every thicket patch. Still, many birders overlook them in their fascination with more brilliantly colored birds. Ornithologists, however, have not overlooked these birds; they’ve studied them closely because they display a rare, genetically based polymorphism. If you look closely, you will notice that white-throated sparrows have two different color phases or plumage markings. This genetic variation within their population is expressed by the occurrence and absence of the yellow lore found between the eye and beak.

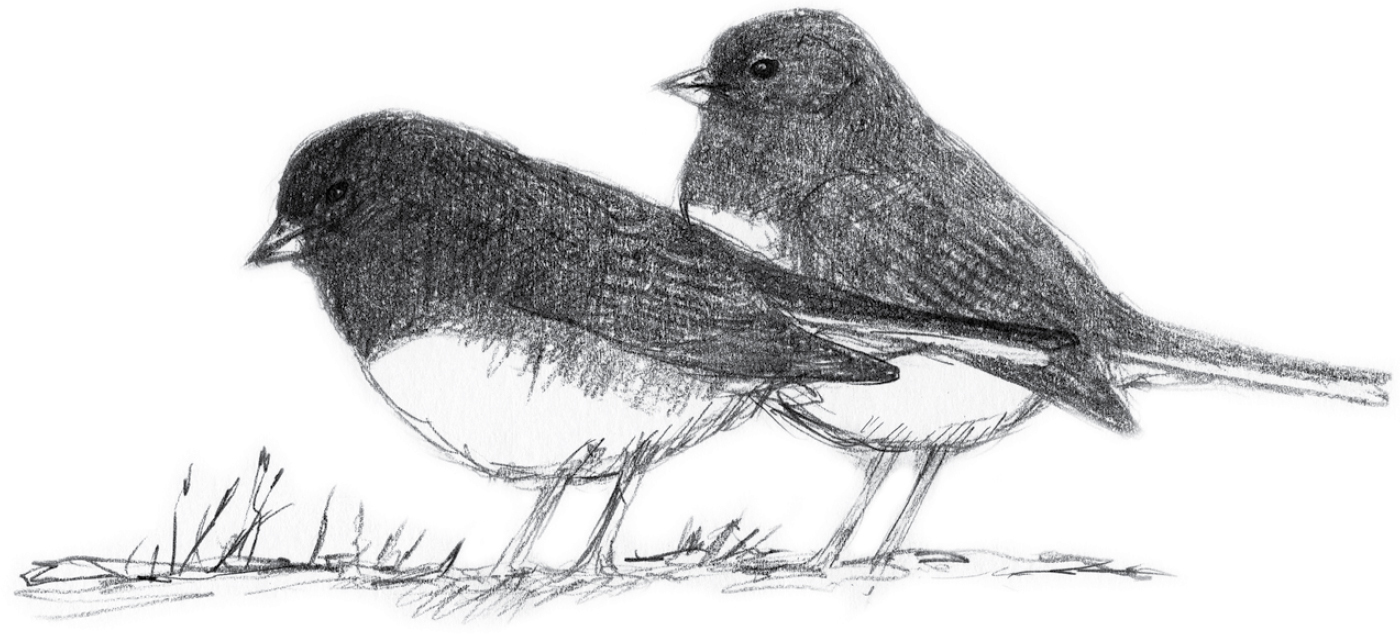

The juncos arrive before the white-throated sparrows in some years, but this year is not one of them. During the peace of the evening, I always make it a point to listen for the juncos. It’s October 12 now and no sign of them yet. Come November, when the sun sets golden and the sky turns a deep, dark, ominous indigo before dark, the mood will be set by the juncos’ calls alone. By that time, juncos will be grouping wherever a brushy thicket or cluster of shrubs exists. They bring the essence of their northland homes to me each fall.

I noticed the other day that the leaves of the birch around town have finally changed from a pale yellow to a darker, richer shade, almost gold. The birch tree in my front yard has done the same, but many of its leaves have already fallen. My birch tree has an interesting history. I bought it for five dollars from a retiree who lives in the town next to mine. He’d dug it up from the woods behind his backyard because the area had been slated for development.

This retiree had spent his entire working life as a developer; he drove a bulldozer and a bucket loader and ran the chainsaws that cut, cleared, and paved the major highways and roads that now run across the state. He said that he felt a nagging guilt, and his way of assuaging this guilt was simple. To make peace for all the destruction, he decided to dig up all the small trees in the woodlot that was about to be destroyed behind his house and find them new homes. He felt the worst destruction was Route 11. It was never officially approved, so they took the initiative and started making their way with the equipment at hand and the time they had to spare. He said it all came to a halt when they hit a ledge of granite, and it has stayed unfinished ever since.

Route 11 is a ten-mile extension highway off our local highway, Route 2. It runs from the center of town out to a rural road in adjacent Salem. Locals know it as the highway to nowhere. Politicians in the area have repeatedly urged that the road be completed, but the uselessness of such an endeavor has kept that from becoming a reality. Given the state’s ongoing and pressing economic concerns, some people have claimed that the highway’s completion to the declining city of New London might help breathe life back into that old whaling town. I think it would still be known as the highway to nowhere. Its completion would require the taking of private land by eminent domain and the carving up of choice acreage that currently filters the water going into the Eight Mile River, which is a watershed of vital interest to the Nature Conservancy, among other groups, as well as being a unique environmental attraction in its own right. It comes down to a battle of wills, much like the situation here in my town regarding the possibility of a huge box-store development.

It’s the same across the nation: chain retailers and industry leaders sweet-talk and campaign through the towns with promises of more jobs and lower taxes in order to get a foothold for their development projects. It all starts with a small proposal and then expands. The box store needs a base, or anchor stores, so they’re soon part of the deal. Before you know it, hundreds of acres are at stake. I’ve seen one mall give way to another and another, resulting in an endless strip. It’s even worse in other parts of the nation. Here in the East, where settlements are much older, strip malls aren’t as extensive, but in regions where development is comparatively new, they’re out of control. In places such as southwest Florida or parts of the West, the malls go for miles, separated by huge divided roadways. These major highways trap residents in squared-off quadrants. One might expect that because these developments are new, some kind of planning should have provided better living conditions. I hope I’m wrong, but I think our great-grandchildren might look back at what we’ve done to the beautiful American landscape and our wildlife and wonder whether we could have cared a bit more.

I think about all this every time I look at that birch tree, which incidentally has grown very quickly in the years it’s been here. All but three feet high when I planted it ten years ago, today it stretches, thin and narrow, a good forty feet. For years I waited for it to turn the color of its namesake, but it continued to reach for the sun wrapped in brown bark. Then, just last year, it broke free of its modest skin and emerged a clean, white birch, just as the man who sold it to me had promised it would.

SOMEHOW THE ENTIRE COUNTY burst into color overnight. The birches took on their famous gold color, the maples a stunning red. The shagbark hickories toasted to a fine umber, but the changes didn’t stop there. The blaze spread rapidly and quickly caught fire to all the species of the forest. It looks as though every color shade between orange and green was burning wild across the landscape in yellows of every tone, with shrubs a lighter shade and sassafras a deeper one. Countless weeds, hedges, and saplings all ignited into flame, their colors stretching from pure-hued reds to saturated browns.

The oaks were also early this year. The early change allowed for various oak species to achieve peak color at a time when many of the maples and birch were still in color. I thought this was very unusual, but I enjoyed the synchronization all the same. The white oaks changed to a faded sable and the pin oaks a woodchuck brown. At the same time, the sumac went to crimson, and I could see other hues of red in the dogwood and viburnum and the swamp maples and sumac.

When the colors peak like this, I’m able to notice each tree as an individual. Green leaves tend to blend with one another, so if you want to tell tree species apart in summer, it’s best to look for differences in texture and shape. Oak leaves are stiff and clustered and sometimes sticky or waxy; they shine and glisten in the noonday sun. The maples are light and wavering and they allow the light to pixelate the distant image of the tree. Softened birch leaves tend to shake with the slightest breeze, while poplars dance and flutter without much prompting.

We all have our favorite trees—specimens so spectacular we remember them from year to year. For me, these include the maple that grows in front of my shed and turns a wild deep-purplish red, and my giant red oak—the one near the deck whose branches shade my garden from the five-o’clock sun—which always becomes a brilliant burnt sienna in the fall.

A hard frost has finally hit, sending every weed and wildflower to seed. A blizzard of crimson hues blows down from the maple, and golden rain showers of birch leaves rapidly spread the news of the oncoming winter. Now that the change is complete, I’m standing in leaves five inches deep, and juncos are flying up everywhere. I want to share this event with someone, but Heather is at school, and I’m alone in the backyard. I make a note that the juncos are here now. It’s the twenty-third of the month.

Very few leaves are left on the trees by the thirtieth. A few young oaks hold on to some ruddy clusters. I believe the juncos arrived on time this year, but the timing of these events is not precise. It depends largely on the length of day, just as it is for any seasonal bird migration. The exact day they’ll arrive in any one specific location depends on many smaller-scale factors, such as local weather and wind patterns. The guarantee is the migration itself. As long as juncos live on the planet, their migration is part of an agreement between the celestial movement of the spheres and the response of living things. I’ve seen so many changes occur just in my lifetime as a result of the quick pace of climate change, however, that the timing and nature of this agreement may someday be compromised. Not this year, though. Sometime in early October, the dark-eyed juncos gathered together throughout boreal forests and took to the skies. They migrated at night, separating from their flocks once en route, and returned alone to where they’d wintered the previous year. They’ve now settled down among the tamer landscapes of eastern Connecticut, frequenting feeders and suburban waysides in search of seed. Like the white-throated sparrow, juncos feed on the ground wherever they find fallen seeds.

The fact that juncos maintain a pecking order makes them extremely interesting to watch. Though they are often overlooked, juncos are constantly maneuvering according to their echelons of power. Males dominate females, and older birds dominate juveniles. Look for tail fanning and face-to-face confrontations. The dominant bird will either be male or a more mature female.

Males arrive first each fall, and they’re easily distinguishable from the females by their darker appearance and absence of brown coloration. The females migrate farther south than the males. Within the southern Appalachians, some junco subspecies often only migrate a few miles, descending in elevation instead of distance to secure warmer temperatures in the winter. In April, juncos return north, but sometimes birders find nesting pairs on higher terrain in Connecticut.

Dark-eyed Junco

The junco is seemingly a different bird once the breeding season begins. The male’s trill begins before the sun rises and doesn’t stop until the first star appears at night. I was surprised when I first caught a junco singing. In northern Vermont where juncos breed, the spruce forests and clear-cuts ring out with the proclamations of this little snowbird.

I DECIDED NOT TO SWIM at the fitness center today because when I walked out the door, the warm autumn air felt so wonderful that even a much-needed swim seemed like the wrong thing to do. I don’t want to compromise my dedication to this exercise regimen, but I can’t pass up a beautiful day such as this. I look up at the light-blue sky emerging from the smoky gold mist still present in the back woodlot and decide that I’ll never be able to relive this day. Now’s the time to enjoy what surely will prove to be one of the best days of autumn.

Instead of getting into the car, I grab my rake leaning against the garage and walk around the corner of the house to the farthest part of the yard. I’m at the apple tree now and have begun raking. I like it back here because birds in the woods on either side of the yard fly across the yard at this point. I’m raking the leaves away from the edges into a pile behind the garden near the butterfly bushes. I’ll rake them onto a tarp and drag them farther into the woods instead of leaving a pile at the edge of the yard and trying to push them or blow them into the woods.

I’ve been at it for an hour now and have raked the entire area behind the garden and near the apple tree. It looks good, and I feel a sense of completion. Perhaps I might have accomplished more had I not been distracted by the activities of the birds. I can’t get over the beauty of the day with its warmth from the sun at its low angle and the cool crispness of the air in the long shadows. The sky is deep blue now, and the morning mist has long since dissipated. I can see far in every direction. I admire the distances, the space, and the multitude of trees in the back woodlot.

It’s not just the birds that have seized my attention. I’m looking at everything. I can appreciate the passing of time in the beauty of my mighty oaks. These red and white oak species are majestic without their foliage on this late-October day. I see the girth, the leaning, the reaching, and the animation of branches. I see the trees next to them and their age in relation to one another. They all tell the story of the sun. The competition for the light is what explains their positions, postures, and different heights.

The hawk’s nest looks conspicuous without the cover of leaves. I think back to those early spring days when this was such an active nest site. My mind is adjusting to the nakedness of the woods. I see a multitude of squirrel’s nests that I’ve never noticed before. I can clearly notice the difference between the creation of the hawks and the shabby oak-leaf nest bundles of the squirrels.

I can see all that, but I can also see much more. I see through the woods to the sky all around me. October is the falling of colorful leaves, but it is also the clearly visible distant horizon. It’s the big picture, the western skyline now visible across the neighborhood, and it’s the very crest of the sun as it appears golden and radiant each morning, materializing at the farthest eastern horizon. It is the revealing of the line that divides all visible directions into earth and sky. The vanishing point at the far horizon, once concealed by the foliage, now yields a magnificence.

After several more hours of work, I’ve raked most of the backyard clear of leaves except for one small pile. The sun is in front of the house, and it might be getting later than I think. Shadows are long across the yard now, and the color has left the sky. An orange reflection in the neighbors’ windows means the sun is near setting out front. I wonder if I’ve truly adjusted to the shorter days. I reluctantly concede that my day in the yard ought to come to an end. After all, my fingers are starting to freeze, and I’m downright hungry.

I can’t go inside just yet, though. I hear geese approaching from the north to northeast. It’s a sound that stirs the emotions and awakens memories. I remember watching the geese fly south as a kid. My friends and I would be playing football in the vacant lot. We would be ready for the next play, but then the sound of the geese would stop me in my tracks. Head up and eyes in the sky, I would wait for them to cruise over us, and I’d exclaim, “Geese!”

Now I’m standing perfectly still and listening with everything I have. I hear their distant gabbling rising and fading, rising and fading, but growing louder all the while. Suddenly I hear the honking loud and clear. They are almost upon me, just beyond the highway and coming in fast. I desperately strain to find them through the naked scaffolding of tree branches but can see only the dark blue of the advancing night. I want to see their long procession and witness the essence of the season. Then, from up into the dusk, a rush of wind—wings, dozens of them, directly above me, roaring like a storm.

I see another group far off in the dusk in perfect V-formation, undulating like a floating ribbon steadily moving south. These I can hardly hear, but the long skein of dots is vivid against the light-blue color above the horizon, where the sun has just set and the clouds are shaded in hues of red. I stand among the last small pile of downed leaves, smelling the rich tannic detritus, while far off the geese disappear into the orange glow of sunset.

I’VE HEARD TALK OF A LATE-SEASON hurricane, a tropical storm grown bold and headed up the coast. After days of listening to the news and speculation about the approaching storm—its trajectory, intensity, classification, and potential for complete destruction—the storm arrives on time as a full-blown category 1 hurricane. We seem to dodge the worst of it, and the winds seem no worse than an unexpected summer thunderstorm. Yet it takes down trees, and we lose power for forty-eight hours. I fumble around with a flashlight, and Heather and I live on crackers and no heat for two whole days. We play a game of Life and pet our cat Stripe by the light of a candle. The skies clear on the second night, and the moonlight illuminates the house. The moon’s light makes it easier to navigate unexpected obstacles, such as Stripe splayed out flat in the darkened hallway.

When the power comes back on, I can’t believe the damage that we see on all the news channels. Just south of here, along the coast and two towns over, the hurricane has brought complete destruction. I see houses shattered in pieces, some split in two and others stranded halfway out to sea, and entire beachfronts pounded and scooped away out into the surf. Famous landmarks are now missing, swept out to sea with the force of the surge. Sand, tons of it, was driven in by the storm surge and spread across neighborhood developments. I wonder what all this would have looked like if it had been a category 5 storm.

Tonight is Halloween—for some people, that is. The celebrations have been cancelled in many towns that still have no power. I found some time to rake the leaves that have blown back over the front driveway and walk. I can’t have little kids slipping on leaves in their costumes. While raking, I think back to last year when three little kids rushed the doorway all at once and managed to wedge themselves so that, when one stepped back after getting his fill, the other two fell over and into the foyer.

Tomorrow will begin the month of November, and the fun of Halloween will be a memory, just like the cool autumn weather. Soon the grip of winter will silence the white-throated sparrow’s urge to sing, and I’ll be left with only their tseep, tseep call notes as the snow silently falls. They’ll remain silent with the junco throughout the coldest days of the winter until some warm April day, when their sweet, melancholy song will again fill the dusk, speaking clearly of the far north they’ve come from. They’ll fly back there by the end of next April. For now, the white-throated sparrow and the junco, both October birds new to the landscape, are here for the duration. They’ll become so familiar that when they leave, we might not even notice their absence.

Tonight, I stock my platform feeder with some added millet for the white-throated sparrows, while off in the distance I can hear the first trick-or-treaters of the night, and I think back over the month. The sight of migrations, of hawks floating on the thermals, the flocks of birds in large numbers, the V-formations of geese, all speak to me of vast seasonal rhythms. Attuned to nature’s timekeeping, and guided by the sun and stars, these creatures follow an unerring instinctual pattern established and carried out over eons. The chilly autumn wind unsettles me. I feel a sense of foreboding about the inevitable advancing cold. Yet despite this my excitement is the same as that of the approaching children—only in my case it’s eager anticipation for the new season of birds.