Introduction

Since the 1950s, Shell’s subsidiary in Nigeria, the Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC),1 , 2 has invested in the communities that host its oil and gas operations. SPDC has built schools, roads, boreholes, community centres and other infrastructure. In 2005, SPDC management decided to implement a new community development strategy that would flip the old model on its head by making the local communities the drivers of development projects with Shell providing technical and financial support. Gloria Udoh, now Social Investment and Local Content Advisor at Shell The Hague—or as she describes it, a “change management professional”—was tasked with implementing the new model. At the time, Udoh was a community development officer at SPDC. She recalls that “interestingly, most of the resistance didn’t come from within Shell, where senior management supported the change. It was local leaders and communities,” says Udoh, who objected. “Sometimes when you hear ‘legacy,’ most people hear about it from a positive context. But in our own case, we learned to use legacy negatively. We went in there with a huge pile of unfulfilled projects. So at first, they [the communities] did not even want to talk to us.”

After years of broken promises, environmental mishaps and conflict in the Niger Delta region, local communities had little trust in Shell. The company had suffered an image problem not only in Nigeria but worldwide, especially after the 1995 execution of Ogoni environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni leaders. In the wake of the Saro-Wiwa execution, SPDC increased its engagement with local communities. However, by the early 2000s, SPDC’s engagement model was becoming unsustainable. The company needed to figure out a more effective way of meeting the needs of local communities without compromising its long term position in the region. Udoh was part of a team recruited by former USAID [United States Agency for International Development] advisor Deirdre LaPin, then working as a consultant for Shell. Under LaPin’s leadership, the team decided to adopt a bottom-up approach to development, what LaPin calls the “leveraged buy-in.”

How does one gain the trust of communities who have been at the short end of broken promises for decades? How does one convince local communities that sustainable models of development would benefit them more in the long run than paternalistic handouts? And how does one make the case to SPDC managers that 50 years of corporate social responsibility practices need to be overhauled? These were the questions that Udoh and her team grappled with as they proposed and implemented what they conceived as a more sustainable model of engagement between Shell and its host communities in the Niger Delta.

Shell in Nigeria: A Brief History

A Huge Footprint in Nigeria

(a) Map of Nigeria (top) showing location in Africa, (Source: United Nations 2014) (b) Map of the Niger Delta showing extent of Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) operations (Source: Shell http://reports.shell.com/investors-handbook/2011/upstream/africa/nigeria.html)

Shell has a huge economic impact in Nigeria. SPDC, for instance, as the largest acreage of any oil company in the country. The company produces about 40% of Nigeria’s crude oil output—the source of 95% of the country’s export earnings and 45% of the country’s gross domestic product (Central Intelligence Agency 2014). Between 2008 and 2012, SPDC paid about $42 billion in taxes and royalties to the Nigerian government (Shell Nigeria 2014). In Nigeria as a whole and the Niger Delta in particular, Shell is a fact of life.

However, the story of Shell and the oil industry in Nigeria has not always been a positive one. Despite its oil wealth, Nigeria remains a poor and highly unequal country. In last six decades, oil companies (Shell included) and the Nigerian government have generated billions of dollars in oil revenue. Yet the majority of the population has benefited little from oil wealth. According to the World Bank, 84% of Nigeria’s population lives on less than $2 a day. Only 40% of the adult female population is literate and 54% of the country’s wealth accrues to the top quintile of the country’s income distribution (World Bank 2014).

The environmental restoration of Ogoniland could prove to be the world’s most wide-ranging and long term oil clean-up exercise ever undertaken if contaminated drinking water, land, creeks and important ecosystems such as mangroves are to be brought back to full, productive health (United Nations Environment Programme 2011a, b).

While Shell maintains that is addressing the UNEP reports recommendations on Ogoniland (Shell Nigeria 2014), the company denies culpability for most spills in the Niger Delta. According to SPDC, 70% of oil spills between 2005 and 2011 were due to sabotage or “bunkering”—the practice by which locals steal crude oil from the company’s pipelines. Nevertheless, Shell has faced multiple lawsuits pertaining to polluted farmland and rivers. In 2013, the district court in The Hague (Netherlands) ruled that SPDC was liable for pollution in a village in the eastern Niger Delta in 2006–2007 because the company had failed to take sufficient measures to prevent sabotage of its pipelines (Sekularic and Deutsch 2013; Bekker and Prelogar 2013).

SPDC and the Nigerian Government

SPDC is the operator of a joint venture partnership called a joint operating agreement (JOA) involving the following partners (participatory interests are in brackets): the Nigerian government-owned National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC, 55%), Shell (30%), Total E&P Nigeria Ltd., a subsidiary of France’s Total (10%), and Italian oil company ENI subsidiary, Nigerian Agip Oil Company Limited (5%) (Shell Nigeria 2014). The JOA covers over 30 oil mining licenses (OMLs) in the onshore and shallow water (swamp) zones in the Niger Delta.

How the Partnership Works

The JOA governs the relationship between the joint venture partners, budget approval and funding of participations by the partners. All partners share the cost of operation based on their participatory interest. Thus, SPDC bears 30% of the operating cost of the joint venture while the NNPC bears the lion share of those costs (55%).

In addition to the JOA, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) governs the fiscal incentives of the partners such as revenue allocation, payment of taxes and royalties and partner margins (Ameh 2005). Under the MOU, partner companies (SPDC included) received a fixed margin within an oil price range $15–19 per barrel. The “split of the barrel”3 (Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria 2004, p. 7), i.e. how much each partner receives as a function of oil prices in the MOU in the years 2000–2004 is shown in Fig. 14.2.

For instance, at an oil price of $19 per barrel, the Nigerian government (represented by the NNPC) receives $13.78 per barrel in taxes, royalties and equity share. Of the remaining $5.22, operating cost and capital expenditure account for about $4 per barrel and a margin of $1.22 per barrel is shared among the other participants (Shell, Total and Agip). At $30 per barrel, the Nigerian government receives $24.13 per barrel, while the margin shared by the Shell, Total and Agip increases to $1.87 and remains at this level beyond $30 per barrel oil price.

Under the JOA, the operator prepares annual work programmes and budgets (Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation 2015). SPDC, as operator, is responsible for the day-to-day running of the agreement and has the most direct contact with local communities covered by the OMLs in the agreement.

SPDC as Operator of Joint Venture Partnership

In Nigeria, an oil-dependent and highly unequal country, SPDC’s host communities have looked to the company to provide infrastructure such as water, electricity and roads that the country’s government had failed to provide, creating a situation in which local communities depended on Shell for basic amenities. In some respects, said LaPin, where Shell ended and the government began was hard to tell. “The Shell style was a colonial style. They inherited it,” she said of the company’s way of dealing with local communities. “A colonial officer and a Shell manager was not an easy distinction to make for those living in the community.”

Furthermore, due to Shell’s relationship with the Nigerian government—through its partnership within the JOA—Shell has also often been seen as colluding with the often-repressive Nigerian government. Things came to a head in the early 1990s. Led by writer and environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Ogonis, one of the many ethnic groups in the Niger Delta, began a high-profile campaign to protest their exclusion from the benefits of oil production and the contamination of their land. In 1995, Saro-Wiwa and eight Ogoni leaders were captured, tried by a secret military tribunal and executed by the government of dictator, General Sani Abacha (British Broadcasting Corporation 1995; CNN 1995).

In 1996, families of the executed Ogoni leaders filed a lawsuit against Shell. The plaintiffs claimed that Shell had been complicit in human rights abuses including torture and killing. Shell, however, denied the charges. After a protracted legal battle lasting 13 years, Shell settled the case out-of-court with a payment of $15.5 million to the plaintiffs in 2009 (Mouawad 2009; British Broadcasting Corporation 2009; CNN 2009).

Given this history, by the late 1990s, Shell managers knew that the company had to change its model of community engagement for “its reputation and to preserve its business,” said LaPin.

SPDC and Its Host Communities in the Niger Delta

Community Assistance

When SPDC started operating in the Niger Delta in 1958, the rules for community assistance were simple. “We would just say, ‘OK, this community probably will need water and we’ll do the water for them,’” says Trevor Akpomughe, a Social Performance Specialist at SPDC, of the corporation’s top-down approach to social responsibility. But, by the late 1990s, that method, carried out for decades, was proving unsustainable. Udoh adds:

We were making the decisions for them [the local communities]…and also constructing the projects, so to a very large degree, their participation was not there in terms of [them saying], ‘this is what our needs are and this is how we prioritise them in terms of making a development journey from where we are today to where we want to be tomorrow.

In addition to the lack of community ownership, the thinking at Shell appears to have shifted. Udoh, a native of the Niger Delta, felt that the issue of change was “very close” to her heart. By the late 1990s, according to Udoh, “[Shell managers started asking,] ‘are we really relating with the communities the way we ought to? Are we involving them in the decisions we make?’”

Also, operational problems within Shell were tasking the paternalistic approach to community assistance. The corporation was providing assistance to some 1000 communities in a piecemeal fashion. For every road or water project in a community, there were several project management committees, which often meant several committees in one community. Akpomughe:

The committees wanted to put as many people to manage things as possible, and nobody was looking at it holistically. That was stretching our resources, because we’re not resourced to do development…So that piecemeal approach was not giving us the best benefits, and our dollar spent was not giving the community a holistic view of how development ought to be managed. Everybody just implements and nobody manages.

According to a 2006 internal report, SPDC had committed to over 400 community development projects and had an outstanding 371 legacy projects to complete.

Often, there was little coordination of the commitments that the company had made to communities. Communities’ resistance to Shell was often legitimate. Not only had Shell made past promises it could not keep, but the company had made some it did not even remember. Udoh says that with so many Shell people interacted with the communities. A courtesy call made by a Shell manager to a community before the implementation of the GMOU could result in a promise for a classroom or some other project. “Sometimes when we were saying that, nobody from the Shell side took an inventory [of the promises] and followed through,” says Udoh of the lack of central coordination and integration. “But the community keeps its own record. So we also had incidences [sic] like that where multiple interfaces, multiple projects, we did not even have a record of them and we said to the community, ‘No we didn’t promise that.’”

But communities usually kept records of promises and demanded that Shell fulfil them. Kudaisi, then a community manager with SPDC, explained the situation:

Some of those [promises] were in the sixties …Community members would say to me, ‘so why are you not coming back after to come and do work with us on the road or do some stuff? You promised us…’ And they bring out the letter [from Shell]. And I say, ‘I don’t know about that, I’m new [to Shell]…But the communities kept saying, ‘you know what; you guys owe us this.

Thus, poor coordination within the company led to broken promises and ill-feeling among many host communities.

Furthermore, when projects were finished, there was no mechanism in place to keep them running. SPDC had to maintain the projects after completion. Udoh: “[When we build a classroom], it is seen as a Shell classroom. And if a light bulb goes off, you get a phone call [from the community], ‘please come and fix your classroom’.” From boreholes that needed refurbishing to town hall tiles that needed replacing. The manpower and financial expenditure of the community assistance model proved to be costly for the company.

By 2004, SPDC was under pressure to reduce expenditures and streamline operations. This made it more difficult for the company to fulfil its community assistance obligations. Akpomughe speaking of the lack of community involvement in projects and the corporation’s financial commitments said:

These two things walked together. The communities needed to pick up the slack, as it were. And it was good that they picked up the slack because otherwise we would still be in the mode where we do things for them and the [community] capacity is not built…. Development should not be handed to them from either a company or from a government without their participation… They need to lead their own development.

But SPDC was spending considerable sums of money in its community assistance programmes. In 1997, according to LaPin, Shell spent $32million on community assistance. This was a huge commitment, but it was coming from an oil company that was not staffed with development professionals—and all that money was yielding little results. LaPin said of 11 community projects she saw in the Niger Delta, she considered only one a success. She wanted to replace the company’s “colonial” approach with a community-based approach to development. “My aim was to change that, to set up an egalitarian, partnership-style relationship between Shell and the community where both sides would be on equal footing.”

In 2005, opposition to the oil industry took a violent turn in the Niger Delta, threating oil revenues, the economic lifeline of the Nigerian government. Against the backdrop of national political crises under President Olusegun Obasanjo, oil supply disruptions and increasing militancy in the Niger Delta, an insurgency group, the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) emerged in the Delta. Well-armed and politically-connected to local elites, MEND demanded equitable distribution of oil rents by sabotaging oil pipelines, kidnapped oil company workers and killed Nigerian Army personnel (Obi 2010). It is estimated that MEND’s attacks led to deferment of 700,000 barrels of oil per day, roughly a third of Nigeria’s daily production output (Watts 2007).

It was in this environment that SPDC senior management realised that the company had to move even quicker to change its engagement model with host communities. “Shell’s community development programme was an attempt to counter that force, the freedom fighters demanding control of oil resources,” said LaPin. Shell moved quickly to implement the new model. “They managed to get $60million up and running in less than a year. I had a staff of 180 including Gloria Udoh, one of the ‘best and brightest’ Nigerian development experts recruited to make the changes.”

A New Approach to Community Engagement

What exactly should replace SPDC’s ad-hoc often paternalistic approach to community assistance? In 2005, Gloria Udoh led a team to propose a new approach to community engagement. The team consulted various departments within the company and studied the community engagement efforts of other oil companies in the Niger Delta, other multinational companies (MNCs) operating in Nigeria and state governments. They found a variety of approaches to community development among these actors. For instance, some companies like telecommunications giant MTN had a non-profit philanthropic foundation funded by the MNC to offer grants to social, educational and developmental ends in Nigeria. One state government had pioneered community development projects in partnership with civil society organisations and local communities to identify “self-help” projects. Udoh and her team also found that Chevron Nigeria, a subsidiary of U.S. multinational oil company Chevron, operating in the Niger Delta, had introduced a model, called the Global Memorandum of Understanding (GMoU) model in the wake of crises that had disrupted its operations in 2003.

In Chevron’s model, development programmes were open not only to its host communities, but spread across communities associated with a “cluster”. Furthermore, Chevron’s model involved inclusion of development stakeholders such as civil society groups, local governments and development agencies (Consensus Building Institute 2008). After the study period—which involved rounds of consultation with Chevron—Udoh’s team recommended to SPDC leadership team the ‘Global Memoranda of Understanding’ (GMoU) approach to community engagement.

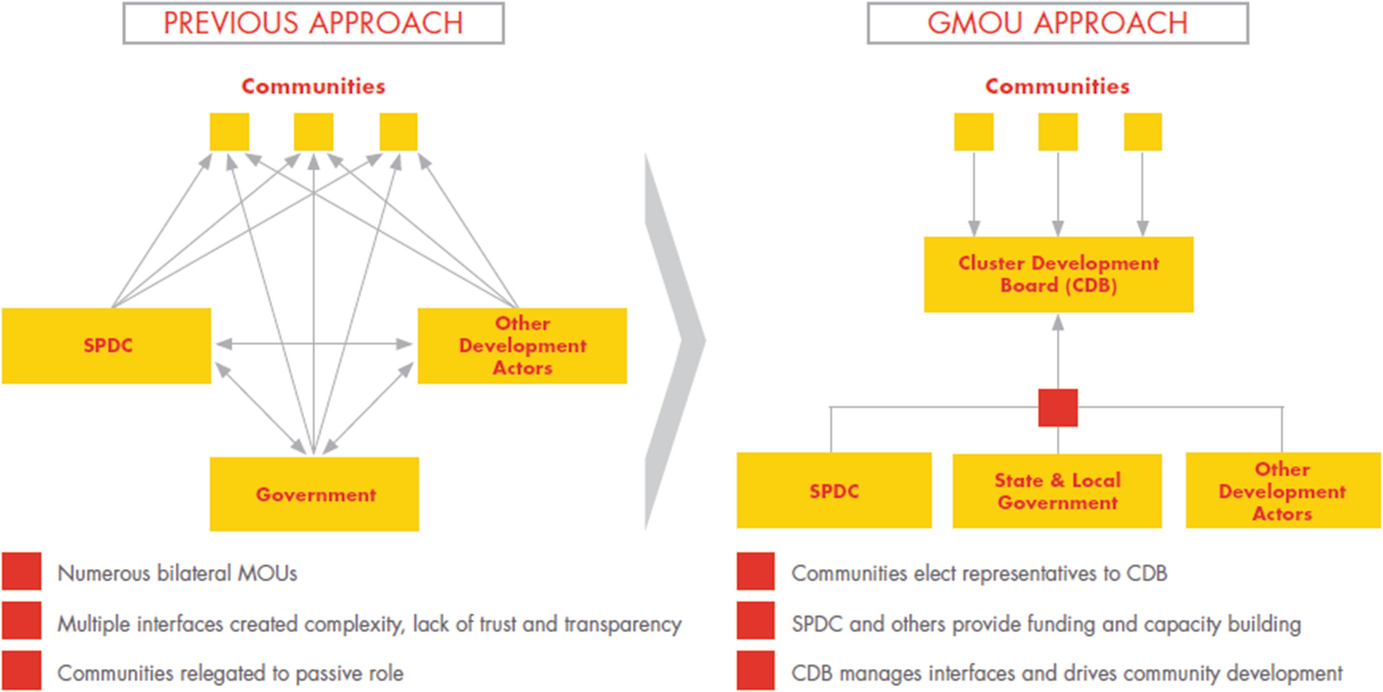

Two approaches to community engagement, comparing the community assistance mode of engagement with GMoU approach (Shell Nigeria 2013)

In the community assistance model, Shell signed multiple bilateral agreements with its numerous host communities and the company was held responsible for community development. In the GMoU model, Shell’s ‘interfaces’ with the communities would be reduced. The number of development projects made more manageable. Shell would provide funding and technical assistance for projects proposed by communities comprising the clusters and would do so for a fixed term (5 years) after which the GMoU would be renewed.

Importantly, in the GMoU model, a wider selection of stakeholders would be involved in development. For instance, the local government would be involved in the cluster development activities. Udoh and her team expected that the government would mediate conflict between the communities. Civil society organisations [non-governmental organisations] would also play a role, helping the communities articulate better their development needs. In the GMoU approach, Shell in partnership with state, local government and NGOs signed memoranda of understanding (MoU) with clusters of communities forming a cluster development board (CDB).

Udoh presented her proposal to SPDC’s leadership team in mid-2006. Mutiu Sunmonu, SPDC’s Managing Director at the time of writing this case, was then Executive Director for Production. He recognised the benefits of Udoh’s proposition. Udoh recalled:

Getting conviction internally was easier than the implementation... Because when we did the study, we said, ‘Fine. From the study we’ve done, we want to go very slowly.’ I said, ‘we want to do six, maybe twelve [GMoUs]. And learn from that before we replicate everywhere.’ The first reaction I had [from SPDC leadership team] was excitement, interestingly. And they said look, ‘if you say this is going to work, do it everywhere.’ And that is also what caused a problem, to some degree, the challenge to some degree [was implementation]…So that was why, after that presentation, they [SPDC top leadership team] said fine, you said this would work, you are very convinced, I said, ‘yes’. They said, ‘OK fine, you go lead the first implementation team.’

Udoh and her team needed a pilot location. “We started looking for other things that would enable the community to take some responsibility off our shoulders,” remembers Udoh. “The turning point was late 2005 with the Gbaran-Ubie project.”

Implementation of the GMoU Model

Pilot Phase Gbaran-Ubie Project

Aerial view of the Gbaran-Ubie integrated oil and gas project central processing facilities (CPF). Arrow shows the direction north (Source: Shell http://www.shell.com.ng/aboutshell/media-centre/news-and-media-releases/2011/gbaran-ubie.html)

Extracts from a GMoU agreement (Source: Shell)

Convincing local communities to sign up to the GMoU model was a difficult task. Udoh and her team had to negotiate a very complex, often emotionally-charged, implementation phase that coincided with the rise of a violent insurrection in the Delta led by militant groups like MEND. Deploying Shell staff and contractor staff to work on the project was difficult due to the threat of violence in the Delta. “Don’t forget, Gbaran-Ubie would be a project that was executed at the peak of the insecurity in the Niger Delta,” adds Kudaisi. “Nobody wanted to be there. It was the biggest project in the worst of times.” Some of the challenges in the implementation are discussed.

Trust between SPDC and the Communities Kudaisi who worked for Udoh negotiating the GMoUs with the communities in the Gbaran-Ubie project recalled:

It was never done before, so you really, really needed to win the trust and confidence of the community, to do what you say you are going to do,” he says. “Grandparents talked about Shell.., I said [to local community leaders] ‘This is the new face of Shell. We all have history.’ You have to win their confidence. We had to address the issue of 50 years of legacy.

Kudaisi remembers setting a deadline for community members to check the archives and cull their grandparents’ memories for Shell’s promises past. In the end, SPDC made trade-offs for promises they could no longer keep. For instance, SPDC had promised a new electricity supply scheme in one of the communities. However, the company did not need to make good on the promise because electricity had already been provided by the Nigerian government. Instead, the company agreed to fund another development project in the community. As part of the budgeting process, the company set aside funds to address all legacy issues in the communities.

Communities largely are built of clans, so one of the things we needed to decide was, ‘how do we cluster communities?’ It would be easier to cluster by local governments, because that means the units would be fewer. So we found that even within local governments, you have various clans and tribes, and they were not historically friendly. We had also put it to the [Bayelsa state] government who then helped with that. The communities don’t mind having a cluster with their own clan, so we then largely went on clan basis

In other areas, however, the process was more difficult. As one interviewee recalled, “Some communities [in the Epie/Atissa cluster] had issues. One of the communities was protesting that they were being attached to a larger community…that had so many facilities [on their land], that they thought they were going to be oppressed. But then, because of the GMoU structure, which was based on what your community is needing and also based on even development, we were able to work together.”

One of the challenges we found all over [in Gbaran-Ubie] was that everybody wants a prestige project like a town hall. But in truth, many of the communities can’t sustain a town hall; they don’t have enough activities to use the town hall, for example. So the town hall is locked [for most of the year]…and it’s really monies that are not properly utilised, it’s for prestige value.

They would want to build a road, a concrete road between the communities; nothing wrong with that in itself! But if you look at the level of development in the community, one of the things we [SPDC] looked at was that if people increase their capacity or generate income for themselves, it’s a much better way to spend development funding because then if they generate income, likely their children will go to school. Their parents would be able to afford books, could afford school uniforms, and things of that nature. We thought to build human development kind of things like a skills acquisition program, but the people wanted ‘hardware’.

He added reflectively, “But it’s a delicate, ongoing process. How do you convince local communities to develop sustainable projects without appearing to impose your ideas from above?”

Equitable Distribution of GMoU funds How would a cluster of communities allocate funds that the cluster had received from Shell? This was a particular thorny aspect of implementing the GMoU in Gbaran-Ubie. It was not clear how to determine the degree of impact on Shell’s operations on different communities. Number of wells? Size of infrastructure? Or length of pipelines? Some communities claimed that they were more impacted than others because their land hosted more pipelines than their neighbours. Other communities challenged such claims with counter claims that their land hosted oil wells, which were more important than pipelines. Yet other communities that did not host large infrastructure feared that they would not get any funding from the GMoU.

The first challenge was getting the governance structure in place. At the time, different people thought that the community members of the governance structure of the GMoU were either going to be paid by Shell or going to get some political appointment or [enjoy] some form of patronage. It took time to explain and to educate them to know that it’s just a service to your society, something you do in the interest of the society. And then of course we needed to validate, check the integrity of some of the nominees. We had to check that through the relevant government authorities and through the traditional institutions, through the governments, and all this. At the end of the day, the nominees were confirmed and certified.

Most of the projects we [the local NGO] were supervising then were infrastructural projects and a lot of money was involved. The kings captured the contractors, the community contractors that were handling the projects. Why the king was able to do [such a] thing? Because the king is the signatory to the work completion certificate. You understand that? So then they were in a position to put pressure on the community contractors to say, ‘If you don’t give me a certain amount of money, I won’t sign your work completion certificate.’

Sometimes people want projects that just benefit a tiny portion of the community. So a chief probably wants a road to go to his house. Now, the NGO will challenge that and say: ‘How does this benefit the women that need to go to the market, or that need to get water? Why is that a priority project and why is this not a priority project? (Akpomughe).

SPDC had to build trust with the state government and convince them that the GMoU approach was going to work. “The relationship with them [the Bayelsa state government] started off rather... best way to say it is, we had to work slowly to develop and establish credibility and trust. I mean, when we started off, they weren’t antagonistic, but they started off remaining to be convinced that we weren’t able to deliver this.

Results of Pilot Phase Implementation

(a) 4 km road built between Shell’s facilities and Gbaran host communities (Gbaran/Ekpetiama cluster). (b) Water tower for the Gbarantoru community (Gbaran/Ekpetiama cluster). (c) Power station for Obunagha and Gbarantoru communities (Gbaran/Ekpetiama cluster). (d) 18–classroom block in Onopa community (Epie/Atissa cluster) (Source: Shell)

Importantly for Shell’s operations, the company did not suffer significant disruption or deferment from local communities in Gbaran-Ubie despite the insurgency in other parts of the Niger Delta.

Implementing the GMoU Beyond the Pilot Phase

SPDC’s leadership team was supportive. After presenting her findings on the Gbaran-Ubie pilot to Shell’s leadership team, she was met with excitement by senior leadership team. They pressured Udoh and her team to move quickly, remembers Udoh, who wanted to slowly roll out the new model. She proposed to implement the GMoU with 12 communities. “They said OK, fine, if you think this will work, you have our blessing. But don’t do just 12. Do it everywhere! So we were now put again under pressure, not having enough resources, even in terms of people on the inside that could run with this.”

With lessons from the Gbaran-Ubie pilot, Udoh and her team began implementing GMoUs with communities in the Delta. Some of the challenges they faced are discussed in detail below.

We introduced parallel officers, Community Development Officers (CDOs), who were representatives of the communities and who listened and asked what they wanted.” The CDO’s job was to help communities act and plan together and to guide them through the process. And importantly, they controlled the funds. The losers were the community liaison officers, who were the primary contacts with local leaders and some of whom were not entirely honest. When we introduced the CDOs, it was a check on their activities and they were advocating for the community. That was a new concept.

The other losers were community leaders, who made the deals with the CLOs, but were increasingly resented by the area’s youth. “This was a more democratic process, so the ‘big men’ were not benefiting much. It shifted the balance of power,” said LaPin. “But the big men had enough good sense to not resist the program, which was beneficial to their community and ultimately to them. But they tried to manipulate it to their advantage,” she reflected with a laugh.

Role of Civil Society Organisations SPDC considers this a “weak area” of the GMoU model. Civil society groups like NGOs [non-governmental organisations] working as part of the GMoU model are ostensibly independent of Shell. In principle, they are charged with pursuing the best interests of the communities. During the Gbaran-Ubie project, according to Kudaisi, NGOs attended cluster meetings to facilitate planning. At the implementation stage, their role was to make sure the projects hit their targets. In practice, however, under the GMoU model, the NGOs are paid by Shell. Critics say there is a lack of long-term planning by NGOs, who still operate in project development mode. A 2010 report commissioned by the Ecumenical Council for Corporate Responsibility (ECCR) included this analysis from Tracey Draper, of NGO Pro-Natura International Nigeria:Many of these communities, they speak different languages. There is no common history. Nigeria is a country that is an artificial creation, we are not like Holland in that even if they break down your [Holland] boundaries today, you would still come back together to one another because you all are the same and you have the allegiance to one king. Sorry, in Nigeria, there is no one king that anyone has allegiance to. It’s a country that was created and if we were given the choice, most of us would not be together. So that’s the reality of the Delta. And it’s worse in the Delta than in other parts…So you have people speaking different languages from one village to the next. Some of them have had a history of conflict.

Weak local NGO capacity has led to NGO staff invariably following instructions from SPDC implementation staff. The NGOs are often unable to achieve an equal dialogue with SPDC and as a result essentially become contractor agents, doing what they are told. The oil industry in general, SPDC included, lacks mechanisms to partner with NGOs effectively. It categorises NGOs as contractors, hired for services delivered in the same way that contractors may be hired to lay a pipe or construct a bridge. (Ecumenical Council for Corporate Responsibility 2010)

There is also the rush to get a piece of the “development pie”. Draper continued, “PNI’s view is that SPDC evaluates NGO performance on how quickly project implementation is completed and exploits NGO fears of losing contracts. In response, NGOs ignore participatory principles and bypass most of the steps to complete projects” (Ecumenical Council for Corporate Responsibility 2010).

Just like it’s done everywhere else, each community is supposed to have a plan. That’s why you have what you call [it a] “local” government, but local government in Nigeria doesn’t really exist. …. That’s why there is a role, that’s the gap that is now filled by the NGOs. Actually, the best would have been to get a local government functionary to get the engineers, work with the communities and come and plan it, get Shell and other oil companies to kind of put money in the pot and get it done with contribution from [local] government.

Nembe: An Exemplar Case

Sometimes getting local communities to the negotiating table was near impossible. One such case was with the Nembe, a group of SPDC’s host communities in the Niger Delta. Udoh says she remembers the Nembe negotiations as if they happened yesterday. “I still remember the first meeting. The chief said to me, ‘Please leave. We are not willing to discuss with you if you are not going to address the outstanding electricity project.’ It was rough”. Udoh appeared to face a particular disadvantage: she was a woman acting on behalf of a mistrusted corporation within in a conservative patriarchal community. The negotiations for the GMoU between Shell and the Nembe lasted for a year.

Despite the acrimony that attended negotiating the Nembe GMoU, Udoh holds it up as “one of the most successful we have.” According to Udoh, SPDC has since begun work on the electricity project that the Nembe chief referred to during her first meeting with the community. Also, “SPDC and Niger Delta Development Commission have also partnered to complete a road linking Nembe to other parts of state.” (See map in Fig. 14.1.) The cluster development board (CDB) (see Fig. 14.3) consisting ten communities signed the GMoU in 2008.

Some of the Nembe GMoU projects, notes Udoh, were self-sustaining. “They [the Nembe communities] became smart,” she said. “For instance, they have a transport business, they have a printing and publishing business, they have a guest house. So the various things they have done have helped them to generate income to add to what they receive. And they also have started engaging other donors to see if they can get funding…the local government at some point also contributed funds. So that’s why I say it is the most successful [GMoU].”

Nembe City Development Foundation (NCDF) in Bayelsa State [a state in the Niger Delta] received a total of $90,000 as counterpart funding from a partnership between PACT Nigeria, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and Foundation for Partnership Initiative in the Niger Delta (PIND) under the Advocacy, Awareness and Civic Empowerment (ADVANCE) programme. The funding received was used for a capacity building programme … for all GMoU Clusters in Bayelsa State. (Shell Nigeria 2013)

Has GMoU Model Been Successful?

By the end of 2012, SPDC had implemented GMoU agreements with 33 clusters covering over 349 communities in the Niger Delta. The company also claims that it committed $117 million to these clusters and that nine of the 33 cluster development boards (CDBs) are registered foundations (Shell Nigeria 2013). But has the GMoU been successful in achieving the goal of community self-reliance? “In a sense it was successful,” said LaPin. “There are better relations with the oil-producing communities, better development in the communities and they are more empowered to plan their projects.” It is unclear whether there is systematic evidence to support LaPin’s claims.

What appears certain, however, is that some GMoUs have been more successful than others. Udoh says of the GMoUs that they’ve “had some brilliant results, some mixed results, and the weak ones are in the minority.” Udoh continued: “So if you were to put it on a 80/20 kind of thing, the weak ones would be 20.” In a presentation to the SPDC leadership, Udoh stated that some GMoUs were not successful due to “to lack of community organisational capacity, poor utilisation of funds and exclusion of some community members.” Furthermore, while the local governments play a mediating role, they have not yet committed funds into the GMoU clusters. There is also a lack of trust in the government on the part of the local communities and the NGOs are sometimes seen as doing Shell’s bidding.

How does one convince local communities that are mistrustful of Shell to change from a mind-set of dependency to one of self-sufficiency? How does a manager win the trust and convince communities to work together in a complex situation like the Niger Delta’s? How does a manager align interests of corporate and community actors in a situation where mediating institutions such as local and state governments are ineffective? These are the challenges that Gloria Udoh and her team wrestled with as they implemented the GMoU model.