Introduction

Shakespeare would have been thrilled by all the intrigues in this relatively new and emerging financial theatre. All the elements are there to write yet another masterpiece – this time on the rise of King Microfinance, his conquering the world and the subsequent gradual decay of his empire. This case study will describe the struggle of one of the king’s knights – ACTIAM Impact Investing – in enlarging the empire in a way that simultaneously serves the interest of the people and the king’s financiers. So what happened?

In 2006 the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Grameen Bank and its founder, Mohammad Yunus. In his acceptance speech Yunus described the launch and development of the bank.

Grameen Bank gives loans to nearly 7.0 million poor people, 97 per cent of whom are women, in 73,000 villages in Bangladesh. (…) We focused on women because we found giving loans to women always brought more benefits to the family. In a cumulative way the bank has given out loans totalling about US $6.0 billion. The repayment rate is 99%. Grameen Bank routinely makes profit. Financially, it is self-reliant and has not taken donor money since 1995. Deposits and own resources of Grameen Bank today amount to 143 per cent of all outstanding loans. According to Grameen Bank’s internal survey, 58 percent of our borrowers have crossed the poverty line.1

In the decades following the launch of Grameen Bank microfinance spread with viral speed. Across the globe initiatives were taken to improve access to finance for the poor, most notably in South and South East Asia, Central America and the Caribbean, and South America. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, microfinance also emerged quite rapidly in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. Assuming that one could do good, while at the same generating high returns microfinance became the ascending star on the financial firmament. The amount of investors rose spectacularly.

Only a few months passed since Yunus’ acceptance speech until the first cracks in the pavement became visible. The wealth of investment opportunities in emerging markets attracted a highly diversified audience of investors – ranging from professional investors to adventurers. It resulted in a somewhat wrought-up market that showed characteristics of what Shiller2 would have called the ‘irrational exuberance’ of the microfinance market. This development led to excesses, damaging the sustainable development of the microfinance sector. Following the initial public offering (IPO) of the largest Mexican microfinance institution (MFI), Banco Compartamos, Muhammad Yunus himself warned against the inflation of microfinance. Instead of opening up the market to allow for more competition benefiting the poor, the IPO primarily resulted in Banco Compartamos’ expansion and its increased domination of the Mexican microfinance market. Among other things, the MFI was criticised for charging its customer excessive interest rates.3 In 2010 a microfinance crisis emerged in Andhra Pradesh following the suicide of a number of microfinance borrowers. And then there were the discussions on excessive interest rates, client over-indebtedness, tax avoidance and a lack of transparency of MFIs that did not really contribute to raising confidence in the creation of a sustainable microfinance industry.

This case study focuses on ACTIAM, previously known as SNS Asset Management, as a medium-sized Dutch asset manager,4 that developed microfinance as a successful business activity. ACTIAM Impact Investing took responsibility for building this particular business line. The objective of the asset manager’s development investment department was to create shared value (CSV) for both investors and investees and to build a sustainable investment practice. The ACTIAM microfinance proposition already echoed the core idea behind Porter and Kramer’s CSV framework – even at a time when that framework was not available yet.

When ACTIAM started its activities in microfinance in 2007, investors were open and sympathetic to the idea of doing good while doing well through their investments. This attitude, however, changed as a result of the financial crisis. Pressured by the European Commission, the European Central Bank, the national central banks, and other supervisory authorities, the appetite for high-risk, long-term, and illiquid investments significantly decreased. Investors changed their policies and introduced tighter risk management procedures. In general, the crisis and all the legislation that resulted from it, such as the Alternative Investment Fund Management Directive (AIFMD), has had a negative effect on the willingness of investors to allocate resources5 to alternative investments – including microfinance.

During the spring of 2007, when ACTIAM launched the first of two microfinance funds it was to bring to the market in just over a year, the situation was different. ACTIAM attracted investments up to an amount of 320mn Euros from institutional investors, including pension funds and insurance companies. At the core of the investment philosophy was the belief that microfinance could and should be beneficial to the poor. Oddly enough, it was not necessary to prove the social value added of microfinance in those days. Microfinance was seen as a contribution to sustainable development per se, which needed no additional proof of its social value for the microfinance borrowers or the communities they lived in. However, that was going to change rapidly, resulting in the integration of the social rationale of microfinance in the due diligence and the analysis of the underlying investments. The funds aimed at providing capital to microfinance institutions, which enabled these institutions to disperse loans to the poor and low-income people. These loans were intended to bring the microfinance clients in a situation of increased financial control. With blue and white-collar jobs being largely absent, access to finance helped the microfinance entrepreneurs to invest in their own business. Without this key social aspect of microfinance ACTIAM Impact Investing’s business proposition would have been void of meaning.6 However, while disbursing loans to microfinance institutions some unintended side effects of microfinance in a global environment came to the fore, which were potentially harmful to micro-entrepreneurs.

This study starts with a description of microfinance and its development in the new millennium. Having introduced ACTIAM Impact Investing and its institutional microfinance funds I then turn to the potential social risks connected to microfinance. A few of these risks impacted the relationship between ACTIAM Impact Investing and its investors, consisting of some of the largest institutions in the pension sector in the world. One intriguing threat that I want to focus on in this study deals with sudden changes in the external environment as a result of social unrest that ACTIAM itself was not instrumental in, but immediately affected the sustainability of its business model. The events taking place elsewhere in the world were kinds of ‘dei ex machina’ for the asset manager and its investors. The relevance of this case study is not limited to the financial sector, including the microfinance sector. Other industries, like the apparel industry, the consumer staples industry or the extractives industry, to mention just a few, face similar problems.

The Case of Microfinance

The Origin and Growth of Microfinance

Microfinance is about providing access to financial services to previously excluded clients. Usually those clients can be found in low-income economies, although microfinance emerges in developed countries as well. It refers to informal and formal arrangements offering financial services to low-income and poor people, thereby focusing on micro-entrepreneurs. Most financial transactions are in the form of microcredit, although (micro) finance institutions increasingly offer savings and insurance products to their clientele. In his book Banker to the Poor, Mohammad Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank, explains that providing credit to poor entrepreneurs provides them with a way out of poverty.

The concept of microfinance is not new. Savings and credit groups that have operated for centuries include the “susus” of Ghana, “chit funds” in India, “tandas” in Mexico, “arisan” in Indonesia, “cheetu” in Sri Lanka, “tontines” in West Africa, and “pasanaku” in Bolivia. In Europe, microfinance dates back to the sixteenth century when informal and small-scale lending and savings clubs were established. In Ireland, Jonathan Swift initiated a loan fund system early in the eighteenth century, using peer monitoring to enforce weekly repayments. In Germany, after the hunger year of 1846/47, Raiffeisen created rural savings and credit cooperatives, originally called credit associations, and currently known as Raiffeisenbanken. The concept of microfinance as it is known today, received wide attention and recognition since the establishment of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh in 1976.

Market development of microfinance assets by MIVs (MicroRate, 2013)

Despite the growth this portfolio there has been a discrepancy between the offering of microfinance services and the alleged need or desire for financial services coming from the underserved communities. At yearend 2012, more than 204 million microfinance clients, of whom 82% are female, made use of microfinance in more than 85 countries. The annual growth rate of clients amounted in the first decade of the millennium to approximately 20%.7

Classifications of MFIs (Microrate 2013)

Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

Description | Mature, financially sustainable, and large MFIs that are highly transparent | Small or Medium sized, slightly less mature MFIs that are, or are approaching profitability | Start-up MFIs or small NGOs that are immature and unsustainable |

Sustainability | (i) Positive RoA for at least 2 of the last 3 years AND | (i) Positive RoA for at least 1 of the last 3 years and other years >−5% OR | The rest |

(ii) No RoA <-5% in the last 3 years | (ii) Positive trend in RoA in last 2 years and >−5% | ||

Size | >$50 million | $5–$50 million | <$5 million |

Transparency | (i) Regulated financial institution OR | Audited financial statements for at least the last 3 years | The rest |

(ii) Rated at least once in the last 2 years |

Microfinance Investors

Investors in microfinance are divided into three groups: (a) governments and development finance institutions (DFIs), (b) institutional investors, and c) NGOs and other retail investors. Governments and DFIs are public investors; the others are private. Together these investors have allocated an amount of microfinance that topped US$ 25bn in 2011.9 Of this funding 60% came from local actors, while 40% was cross-border.10 DFIs and multilateral organizations, like the World Bank, IFC and EBRD, provided more than half of all foreign investments whereas institutional investors contributed significantly to the growth of microfinance in the last few years – particularly in the area of private equity investments. This group of institutional investors included international banks, pension funds, and insurance companies. The impressive growth figures have sometimes been interpreted as a sign of a maturing microfinance. In addition, it has been used as an argument for demonstrating the attractiveness of microfinance for institutional and other ‘finance first’ investors – at a time the jury was still out. Microfinance has gone through a “process of transformation from a sector dominated by a mission-driven ethos to one responding to the needs and interests of private capital”.11 Somewhere during the middle of the first decade of the new millennium the impression started to take root that microfinance was socially and financially attractive. Microfinance was believed to have the potential of adding value to institutional investors in terms of attractive risk-adjusted returns, social value and a low correlation with other asset classes. It did not take long to correct this view as being naïve and even detrimental to the poor. The price for getting access to finance was high, as both investors and borrowers were soon to find out, and very often for good reasons. Sometimes it was too high – leading to social unrest and protest. Examples came from the No Pago movement in Nicaragua,12 the LAPO incident in Nigeria13 or the Andhra Pradesh suicides14 and will be elaborated briefly later in this contribution. These examples increased investor reluctance to invest additional capital in the industry.15

ACTIAM Impact Investing

The Trend Towards Responsible Investments

The start of the new millennium sparked the beginning of a new wave of socially responsible investing (SRI). In the twentieth century SRI particularly focused on social, ethical, and environmental policies, practices – and to a lesser extent performance – of multinational corporations. Following the IT-bubble – which to a large extent demonstrated some clear shortcomings in the governance of companies – the SRI-debate shifted. Governance-issues took centre stage, opening up opportunities for institutional investors to enter the space. In 2004 Mercer and UNEP-FI coined the term Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) to replace Social, Ethical and Environmental (SEE). The notion of governance was much more acceptable to institutional investors facing their fiduciary responsibility towards their beneficiaries. The shift became even more relevant to investors when research demonstrated that improved corporate governance would result in financial outperformance. As a result non-financial issues were integrated in the fundamental financial analyses of companies.

In the financial bull market that followed the IT-crisis, the institutional investment community was open to a host of innovative investments that looked for excellent financial and non-financial returns. In this environment ACTIAM – a medium-sized Dutch asset manager – stepped up its initiatives to become ‘The Responsible Investor’. In itself, that was not something new for the company. In the 1980s the company integrated social and environmental factors in the process of stock selection on behalf of a Dutch ethical bank. In 2006 the company decided to integrate ESG-criteria in the entire investment process – broadening the scope from stock selection to the selection of all assets.16 The process was guided by the ACTIAM Fundamental Investment Principles (FIPs), which were based on the United Nations Global Compact and relevant international treaties. The idea was that the asset manager would not prioritise its own morality or that of its investors, but would take international conventions, treaties and agreements as its benchmark that were issued by authoritative organisations like the UN, ILO or OECD. The FIPs refer to (the avoidance of) violations of human rights, labour rights, corruption, controversial weapons, environmental protection, and client and product integrity.

The core of the ACTIAM’s responsible investment approach was to avoid or exclude very serious violations of its principles, while it juxtaposed this strategy with an attempt to improve the performance of its investments. To an outsider it may seem odd to want to avoid only very serious violations of one or more principles. As a result, it could occur that ACTIAM condoned mild forms of child labour, human rights violations, corruption or environmental degradation – and actually that is what happened. Every investor faced – and faces – this dilemma when allocating assets. The reason is that large chunks of the investment universe of large cap companies, nearly per definition, were – and are – involved in some sort of activity that is socially, ethically or environmentally undesirable. It is for this reason that ACTIAM invested in engagement with companies involved in undesirable activities or behaviour, but that were not seen as the worst offenders.17 By focusing on the gradual integration of ESG-factors in its portfolio management and on engagement ACTIAM was saying two things. First, the organisation expressed its concern for the social, environmental and governance side of investing. But secondly, it clearly stated it was in the business of investing – not in one of excluding – with the exception of serious violators of its principles. We should not be misled by the idea that avoiding undesirable practices changes anything to the occurrence of undesirable or reprehensible practices. The problem simply moves from one investor to another – that is, to an investor who remains committed to the company, the country or the project that others avoid. The investee will not be impacted by an investor’s decision to divest when there is sufficient liquidity in the market willing to invest in the investee. This was and still is a key issue for institutional investors.

Launching Two Microfinance Funds

Apart from the avoidance of harm – which is basically what the investment principles were all about – ACTIAM also wanted to make a positive contribution through its investments. For that reason it launched its first institutional microfinance fund in 2007: the ACTIAM Institutional Microfinance Fund (AIMF). With assets under management of approximately €160mn the launch was very successful. Soon after, a second fund followed in 2008. The ACTIAM Institutional Microfinance Fund II raised an amount of capital comparable to the first fund. Both funds were non-listed mutual funds open to professional investors only. At the time the exclusive focus on pension funds, insurance companies and professional asset managers was quite unique. The funds are closed-end – leading to a situation in which ACTIAM Impact Investing actively participates in the fiduciary responsibility of the pension funds, insurance companies and professional asset managers on whose behalf it invests.

A Different Business Model

The fiduciary responsibility of ACTIAM’s investors referred to their duty to invest the capital in the best interest of their beneficiaries. Practically speaking this meant that the investors were looking for market-rate returns. They considered themselves ‘finance first’ investors18 – as opposed to foundations, family offices and High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) who are usually referred to as ‘impact first’ investors. Nevertheless, also institutional investors would want to look for investment opportunities that led to a world worth living in – then, now and in the future. It is precisely this ‘double dividend’ the ACTIAM Institutional Microfinance Funds were targeting. To serve its investors in an environment that continuously raised the bar regarding the application of professional investment standards ACTIAM Impact Investing developed an innovative business model. That is, ACTIAM operated – and still operates – as fund manager on behalf of the fund participants, while leaving the selection and monitoring of the investments up to an independent investment advisor. ACTIAM, therefore, was responsible for structuring the fund, fund governance, investment decision-making, monitoring the investment advisor and constant communication and reporting vis-à-vis its participants. The investment advisor took care of sourcing the investment deals, due diligence, writing the investment proposal and monitoring the MFIs once the ACTIAM Investment Committee decided to invest. For both funds ACTIAM selected Developing World Markets (DWM) from Stamford, Connecticut as its investment advisor. By creating this structure and dividing responsibilities between itself and its investment advisor the fund manager maximised the chances of working in the interest of both the investors and the investees in a cost-effective way. The structure contributed, for instance, to the prevention of ‘deal blindness’ – a not uncommon characteristic among investment managers deciding on deals they sourced themselves. The division of labour also meant that the best skills were working to provide maximum result in each step of the process. ACTIAM employed portfolio managers and relationship managers with an adequate understanding of the institutional investment market and of the microfinance market. DWM employed specialists familiar with sourcing, analysing and monitoring deals on the ground.

Investments

Since inception the first ACTIAM Institutional Microfinance Fund has made more than 256 loans to 123 microfinance institutions for a total amount of €591mn.19 Fund II has provided a total of €260mn through 184 loans to 99 MFIs. Finally, the funds took equity stakes in 6 MFIs. The loans and equity investments have mainly been disbursed to MFIs in South America, Central Asia and the Caucasus, and South and South East Asia. Africa was clearly lagging behind due to high investment risks. In an environment where fixed income investment returns declined significantly in the developed world between 2007 and 2015 the ACTIAM Funds returned somewhere around 5% annually to their investors – net of management fees and of other costs.

Performance of the Funds

Looking back on more than 6 years of microfinance investments, what has been achieved? Did ACTIAM Impact Investing succeed in creating a decent market-rate return for its investors, while at the same time creating social value for the MFIs ACTIAM invested in and their clientele?

From a financial point of view the ACTIAM Institutional Microfinance Funds performed quite well. At the end of 2012 both funds provided a return to the investors of somewhat over 6% on the debt part of the portfolio – net of costs and net of fees. Compared to the SMX Index,20 which returned 4.05% in 2012,21 that leads to an outperformance of over 200 basis points (bps). But what can be said about the social performance? Did both funds actually live up to the expectation of creating added value for the micro-entrepreneurs the ultimately want to assist in getting access to finance.

AIMF I Outreach

AIMF I Improvements in MFI Focus and Management

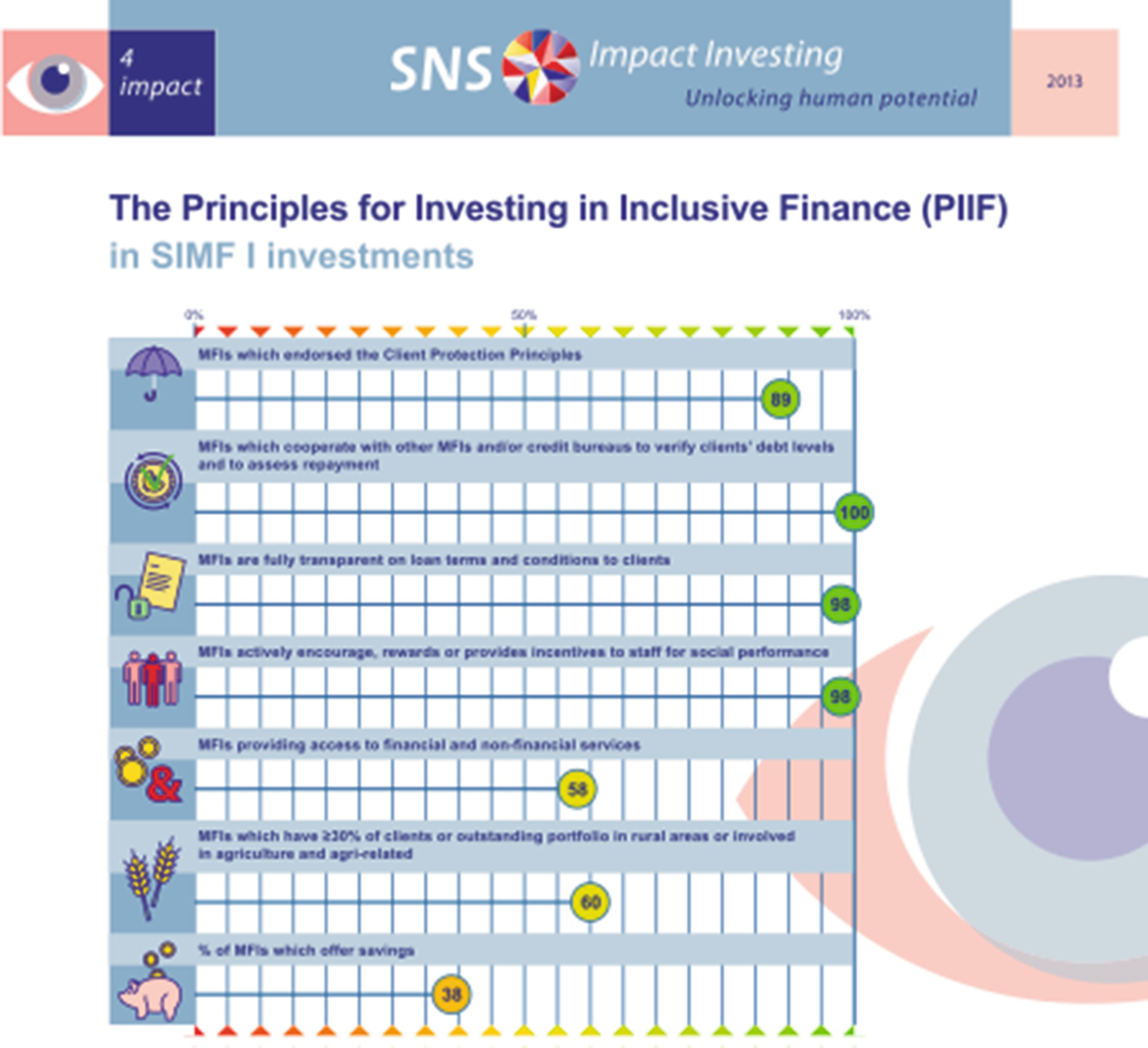

As the Eye4Impact illustrates, enlarging capital for Western pensionados while enhancing the opportunities of the poor to get access to finance can go hand in hand – even though there is still plenty room for improvement. The next section will point out that this unfortunately is not always the case in microfinance across the globe.

Creating Shared Value

Mohammad Yunus saw microfinance as an example of creating shared value ‘avant la lettre’ by developing a range of financial products that enhance the business opportunities, capabilities and skills of poor micro-entrepreneurs. Porter and Kramer could have referred to microfinance if they would have wanted to point to an opportunity to increase society’s productivity and the development of a new market. “The concept of shared value”, they argue, “recognizes that societal needs, not just conventional economic needs, define markets”.22 That was precisely what Yunus had in mind when he provided access to financial services in order to alleviate poverty and offer an alternative to the so-called ‘loan sharks’.

When ACTIAM launched its first two funds, microfinance institutions across the globe were looking for foreign direct investment capital to grow their businesses and to provide access to finance to poor people.23 At that time most of this capital was still supplied by NGOs and DFIs. The rise of microfinance investment vehicles (MIVs), bringing private capital to the market, was seen as a welcome addition to the opportunities for MFIs to attract funding.

At the time of their launch the funds aimed to expand “the total pool of economic and social value”24 by adding two characteristics that were quite innovative. In the first place the funds were exclusively open to institutional investors. Secondly, they were closed end funds that allowed for the provision of loans in local currencies. Both elements offered MFIs a significant advantage. The commitment by institutional investors to accept a tenor of at least 7 years contributed to the credibility of the microfinance sector. Apparently, institutional investors like pension funds or insurance companies were willing to provide capital to micro-entrepreneurs who had no or only very few assets – albeit via MFIs. In addition, the funds provided an opportunity to provide loans with a longer tenor and in local currencies – leaving some of the currency risk with the investors.

Bad Moon Rising

Assisting the Poor?

Since 2007 a number of crises emerged across the world that were related to microfinance. With the benefit of hindsight we can conclude that most crises were not incidents but foreseeable accidents waiting to happen. They were the result of a mix of ingredients that turned out to be poisonous to at least some of the microfinance borrowers. Before the 2006 ‘Krishna crisis’ emerged in Andhra Pradesh25 (AP) the financial markets in the developed and the developing had a positive outlook on the potential of microfinance. Even after this crisis the optimistic sentiment persisted. As was explained in section “ACTIAM Impact Investing” vast amounts of foreign capital were flowing into the market leading to an environment based on conditions that did not contribute to the creation of a sustainable microfinance market. The flow of capital allowed MFIs to grow very rapidly on a commercial basis. Money became an easy to get commodity without borrowers being sufficiently aware of the conditions and the consequences of borrowing too much money. Interest rates were high and sometimes excessive, MFIs forced borrowers to save and used unethical recovery practices, and entrepreneurs ended up with having 2, 3 or even more loans.

The Krishna crisis may have provided the first sign that microfinance was more than a tool to alleviate poverty and it certainly wasn’t the last. Analysts, like Ramesh Arunachalam, pointed out that microfinance gradually became a risk as a result of the lack of appropriate regulation and oversight, combined with improper business conduct by loan officers and debt collectors. The potential risks not only became manifest in India, but also in Mexico and Nicaragua.

Mexico

Compartamos Banco is the largest MFI in Mexico. In 2007 the board of what at that time still was a non-governmental organisation, decided to go public. By floating an Initial Public Offering (IPO) on the Mexican Stock Exchange the bank netted a little over US$400mn for its shareholders. In 2 years time, then CEO Maria Otero received a compensation of more than 2 million USD. At the same time the poor were paying annualized interest rates of more than 100% on a loan.

Nicaragua

In January 2009 the Movimiento de Productores, Comerciantes y Microempresarios de Nueva Segovia blockaded the Panamerican Highway. The protesters introduced the phrase that would echo in Nicaraguan and even international politics for more than 1 year: ‘No Pago! No Pago!’26 The No Pago Movement, consisting of some 10.000 members, was largely fuelled by complaints that MFIs charge interest rates that are too high, leaving borrowers swamped in unmanageable debt. The movement lobbied for the passage of a debt relief law that would fix the maximum chargeable interest rate at 12%. On 1 October 2009 protesters scored a major victory when legislators signed a bill supporting the passing of such a law. The proposal gives debtors an interest-free, 6-month grace period and up to four to 5 years to fully repay their loans.27

Andhra Pradesh28

The Andhra-MFI-Ordinance states: “(3.1) All MFIs operating in the State of Andhra Pradesh as on the date of the commencement of this Ordinance, shall within thirty days from the date of commencement of this Ordinance, apply for Registration before the Registering Authority of the district specifying therein the villages or towns in which they have been operating or propose to operate, the rate of interest being charged or proposed to be charged, system of conducting due diligence and system of effecting recovery and list of persons authorized for conducting the activity of lending or recovery of money which has been lent. (3.2) No MFIs, operating at the commencement of this Ordinance or intending to start the business of lending money to SHGs, after the commencement of this Ordinance, shall grant any loans or recover any loans without obtaining registration under this Ordinance from the Registering Authority.”29 These two paragraphs from the ordinance that the government of Andhra Pradesh passed on 15 October 2010 caused a shock in the Indian – and global – microfinance community. The ordinance entailed that MFIs with pending registration had to cease operations in Andhra Pradesh immediately. They were not allowed to collect loans and interest payments, which had a significant impact on their liquidity. The ordinance followed reports on unethical recovery practices and suicides as a result of client over-indebtedness.

Add to these examples the accusation in the spring of 2013 that microfinance investment vehicles made use of profit shifting and avoid taxes,30 and the impression is easily created that microfinance is rather poisonous – for investors and for microfinance borrowers. It led MS Sriram at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad to conclude: “a fairy-tale had turned into a nightmare”.31 It is important to note that ACTIAM funds were not invested in Compartamos Banco or in India at the time of the AP crisis. The funds were, however, invested in a Nicaraguan MFI that went bankrupt as a result of the crisis. Ultimately, the investors paid the bill for the bankruptcy of the MFI, although the cost was rather limited.

Consequences for Institutional Investors

The conference leader, Sam Daley-Harris, was about to reach the climax of the entire spectacle, when he would reveal the number of people who had been “reached” by microfinance. (…) It was something like 100 million people. (…) We, the people in this room, had performed a miracle. (…) We were no longer a fringe activity; we had 100 million clients. We were superheroes, apparently, and the microfinance sector even had a Nobel Peace Prize under its belt. (…) Sam clarified. “I would like to propose a round of applause for us, those in this room, who have worked so hard to bring this about. It is thanks to you that this has been possible, and I think you deserve a round of applause.32

In Halifax, the Krishna crisis had already taken shape, although the crises in Mexico and Nicaragua were still concealed in an unknown future. In the years following the summit even the most ardent proponents of microfinance were convinced of the necessity of change. The dream was over. Nevertheless, there was no reason to throw out the baby with the bath water because some MFIs fell prey to mission drift and shifted their attention towards commercializing their operations in an unethical way. There was still a need for access to finance for the poor – albeit in ways that match the needs and the abilities of poor to handle a microloan and all that comes with it. According to the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) and the World Bank (2010) around 2.7 billion people still lacked access to formal financial services implying a capital requirement of some USD 250–300 billion. Some of that money could come from domestic investors, but not all of it. Foreign direct investments remained an important source of funding for microfinance institutions – be it with the right specs that made it possible for MFIs to offer microfinance loans, saving and insurance in a commercial, but responsible way. Providing access to finance through microfinance products and services is relatively expensive – particularly in the not so densely populated rural areas. But that should never lead to usury, to mandatory savings (certainly when practiced without giving fair compensation to the client), or to the use of oppressive recovery practices.

Creating Shared Value as a Normative Challenge?

In this book De los Reyes and Scholz challenge the framework of creating shared value (CSV) to adequately address normative issues and corporate social responsibility (CSR). The authors take issue with Porter and Kramer’s approach and their idea that the “essential test that should guide CSR is not whether a cause is worthy but whether it presents an opportunity to create shared value”. More in particular, they argue that CSV “is ill-suited to handle common managerial scenarios where profitability cuts into social welfare or vice versa”33 Business will not regain its legitimacy by simply creating shared value and stimulating economic growth for a community and those who are part of that community. More is needed, and that particularly includes an integration of normative analysis in the CSV framework to address issues of redistribution and responsibility. Even though CSV may be a necessary requirement to align societal and business interests, De los Reyes and Scholz continue, it is not a sufficient component for business to redeem societal trust and win back its legitimacy. To that extent the authors offer a conceptual framework called SWONT, an abbreviation of Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Norms and Threats.

The authors have a point in addressing the normative quality of the CSV framework, which is relevant for this chapter. ACTIAM Impact Investing considered itself to be an enlightened asset manager, consciously serving both the interests of the investees as well as those of the investors. As was shown in the previous paragraph it faced several ethical challenges and opportunities in its attempt to provide capital to MFIs in a responsible way. In this respect, it acted in line with Porter and Kramer’s CSV framework. So what can be said about the moral compass that CSV offered to ACTIAM? Was it sufficient? Should it have been supplemented by an explicit normative analysis as part of the strategic planning process? In this section I will spend a few words on the relevance of the discourse between CSV and SWONT, discussing the approach that ACTIAM took in the next section.

Creating Value Versus Redeeming Legitimacy

Porter and Kramer’s claim that business can redeem corporate legitimacy by implementing CSV more of less has become the framework’s Achilles heel. A more modest approach in which the authors simply would have demonstrated that CSV contributes to winning back public confidence and trust, would likely have prevented an argument on the (lack of) ethical quality of the framework in its current, pronounced form as I hope to demonstrate in the remainder of this article. Even though Porter and Kramer suggest that CSV can help business to regain its societal legitimacy, the framework not about awarding or allocating moral praise for solving society’s problems. It simply is the intelligent business attempt to create economic and social value for business and society by listening and responding to the needs of society. It sees and conceptually frames societal problems as business opportunities. CSV is, therefore, all about common (business) sense – whatever social motives the owners and managers may have had when they started their CSV activities. The question then arises whether De los Reyes and Scholz aren’t exaggerating their argument? Aren’t they missing the point that managers, operating in an open and dynamic society and focusing on simultaneously creating sustainable long-term value for the business and for society, will incorporate normative arguments in their decision-making? It may be true that in Porter and Kramer’s CSV framework ethics has become a caricature to the extent that it lacks guidance for managers dealing with difficult ethical challenges and choices that cannot be explained and answered by a reference to the creation of shared value. The question is, however, does this perceived lack of guidance require adding a normative analysis to the existing SWOT-model? Wouldn’t such an addition fail to appreciate that managers who are focused on long-term value creation for business and society are savvy when it comes to integrating ethics – even if they do not receive explicit guidance from Porter and Kramer? Managers are challenged by customers, NGOs, politicians, media, academics and, not at least, their own employees regarding issues of sustainability and ethics. In a global business environment – which is the environment De los Reyes and Scholz implicitly put centre stage – these are and have to be alert and responsive to the needs of society as a conditio sine qua non, with or without the support of the CSV framework. The value of Porter and Kramer’s framework rests in their constant focus on opportunities for business to turn society’s problems into corporate action that is both profitable and societally valuable. Those opportunities can be found everywhere across the globe – even in situations that seem quite unlikely today. It is the strength of the CSV framework that even when dealing with, for instance, the poorest of the poor, there are ways in which a business approach to solving society’s problems can be beneficial to the poor and to society in a responsible way. The case of ACTIAM Impact Investing demonstrates that – even in absence of ethical guidance from the CSV framework – no SWONT model was required to conduct business in a responsible way.

A Clear Challenge

The sustainability of ACTIAM Impact Investing’s business model was tested during the microfinance crises mentioned previously. Even though the asset manager was not directly involved in two of the three crises, it certainly faced some tough questions from investors, colleagues and the outside world. Microfinance’s honeymoon came to a sudden and unexpected end when it appeared to have negative social effects on the lives of poor and low-income people – in addition to the value it created in allowing microfinance clients to have access to financial service and better manage their financial needs.

This unexpected development caused concern among (institutional) investors. In an environment that was confronted with the aftermath of the global financial crisis – with limited risk budgets available for niche products – institutional investors became somewhat wary to make high-risk investments in developing countries. The investment opportunities needed to be large enough to justify the high costs involved in microfinance investments. In addition, the fiduciary responsibility towards their beneficiaries required pension funds and insurance companies to generate market-rate returns. But most of all, they saw a reputation risk arising in making impact investments in developing markets in general and microfinance investments in particular.

The ACTIAM Institutional Microfinance Funds were not confronted with an outflow of capital as a result of the events taking place across the globe because they were closed-end funds. Investors were simply not able to reclaim their investments. Despite this characteristic of the funds that kept all investors on board, ACTIAM faced the reputation issue heads on. In tackling the reputation issue the organisation’s development investment arm did not operate in a moral void. On the contrary, the fundamental investment principles and ACTIAM’s culture of being a responsible investor provided clear guidance.

Expanding the range of financial services available to low-income people;

Integrating client protection into all their policies and practices;

Treating their investees fairly, with clear and balanced contracts, and dispute resolution procedures;

Integrating ESG factors into their policies and reporting;

Promoting transparency in all their operations;

Pursuing balanced long-term returns that reflect the interests of clients, retail providers and end investors; and

Working together to develop common investor standards on inclusive finance.

The use of benchmarks to assess acceptable Return on Assets and Return on Equity levels,

Implementing a stricter focus on remuneration and incentives of MFI management and staff as part of the due diligence and monitoring of MFIs. No ethically questionable incentives – such as (excessive) bonuses for bringing in new clients or collecting interest and loan payments – will be condoned,

Reinforcing policies and analysis regarding the risk of over-indebtedness in portfolio countries,

Supporting the launch of credit bureaus in developing countries.

Finally, ACTIAM became a member of the Social Performance Taskforce (SPTF), initiated a round table with other MIVs to discuss the development in highly saturated markets like Peru and Cambodia, and led the study on microfinance and tax avoidance by the Dutch National Platform for Inclusive Finance (NPM).

In order to manage and mitigate the (reputation) risks, which had emerged over time in the microfinance space, ACTIAM increased and improved investor communication. In order to educate investors, the asset manager outlined its view on social value creation in a separate paper. In addition, the organisation issued regular newsletters in which relevant topics were addressed. Finally, ACTIAM organised field trips to MFIs for its participants. These 3–4 day excursions had the character of a study trip34 in which MFI visits were combined with meetings with sector representatives, national banks, and, of course, MFI clients.

Good Business Sense

Despite this negative effect on the cost of the operations, ACTIAM continued focusing on reducing the risks for its investors, investees and microfinance borrowers. Not only was this decision the result of the ACTIAM culture and its investment principles, it was also motivated by the idea of good business sense. Ultimately, ACTIAM wanted to contribute to building a strong and responsible financial sector in which access to finance for poor and low-income people is fully integrated. One can only achieve this aim by focusing on the long run. Integration of financial services for poor and low-income clients takes time – much time. Only those asset managers will be around in the decades to come that ultimately have the patience and the business sense to see the social needs and objectives of end clients, MFIs and investors as part and parcel of their strategic business model – and act on it.

The case demonstrates that a strategy focused on creating shared value does not necessarily preclude a focus on normative ethics. In an open and dynamic society and with a clear focus on long-term shared value creation managers will be sensitive to the moral claims of the stakeholders. The primary reason for ACTIAM Impact Investing’s management to be responsive to the social needs of microfinance clients was not a sense of moral obligation – although the ethical appeal coming from NGOs and the media resonated well with management – but the anxiety of investors to be exposed to reputation damage. The leading question for management has, therefore, been:

What can we do when our products and services meet society’s responsibility standards to prevent being challenged by our clients and the outside world when the sector in which we operates is falling from grace?

Shakespeare’s Tragedy

Present-day stories about ‘No Pago’, Compartamos Banco, or the Andhra Pradesh crises could have provided Shakespeare with interesting material for modern drama. Whether reading Julius Caesar, Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth, Henry VIII and not to forget Richard III, self-interest and betrayal are common characteristics in his historical plays and tragedies. Not always for the wrong reasons, as Marcus Brutus shows in Julius Caesar. Brutus is truly concerned with Julius Caesar’s ambition to turn the Roman republic into a monarchy under his rule. Brutus teams up with conspiring Roman Senators to assassinate Caesar. Despite being erroneous about Caesar’s motives and intentions, both friend and foe considered Brutus to be ‘a noble man’. He acted for the good of Rome.

Mohammad Yunus may have felt like Julius Caesar when microfinance became a tool that could turn itself against the interests of the poor. Yunus’ idea of microfinance becoming an omnipotent instrument for poverty alleviation turned into a nightmare in some cases. Against the background of the potential downsides of microfinance, ACTIAM Impact Investing faced some challenges when it simultaneously tried to serve the interests of the poor and of its investors. High investor returns resulted in undesirable social outcomes, which had to be balanced with the provision of sufficient capital to provide access to finance for poor and low-income people. Too strong a focus on eliminating poverty by offering low-cost loans and technical assistance to microfinance institutions would, on the other hand, result in an outflow of (institutional) capital in the long run.

ACTIAM found a middle of the road approach by attracting foreign capital to improve the access to finance for poor and low-income clients to increase their ability to better manage their financial affairs. This obviously required a vision and a focus on the asset manager’s responsibility in terms of the prevention of excessive interest rates, over-indebtedness, or unethical recovery practices. In addition, ACTIAM and its investors were determined to contribute to a professionalization of the sector. This could, for instance, be done by speaking out on the necessity of regulation, promoting transparency, supporting the creation of credit bureaus, or building an environment in which microfinance could develop into a profitable sustainable financial practice. Poor and low-income people are willing to pay for high-quality services when the contractual conditions are fair.

Serving the interest of both business and society is in need of managers – operating within a CSV framework – who demonstrate to be streetwise in an ever-changing business environment. They need to be – and very often they are – savvy in incorporating the needs of their stakeholders in a dialectic relationship between business and its environment. This means that the CSV framework implicitly incorporates normative elements that Porter and Kramer disregard. On the other hand, there is not need for adding the ‘N’ to the SWOT-analysis. Analysis and discourse on social, ethical and environmental issues that managers meet along the way of implementing their strategy, are part and parcel of the conditions of doing business in a modern economy.35 The example of ACTIAM demonstrates that, with an open mind and a responsive attitude, companies are able to engage in normative analysis, discussions and actions to address (social) threats. They can contribute to a Shakespearean drama by taking the material of the table with which Shakespeare used to write his compelling tragedies. That, in the end, is the real tragedy: Shakespeare having nothing tragic to write about anymore.