Introduction

Many companies have made commitments to some form of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and/or sustainability. Stating that a company is involved in CSR or sustainability can mean many things as there is no universal, agreed view of CSR or sustainability. Responsibility and sustainability are descriptive terms that always require qualification provided by other words and more importantly actions. In practice these big ideas are associated with a wide range of organizational practices that are complex in their formulation, implementation and impact on the company. By definition responsibility and sustainability also have implications for the wider environment and society and the economic systems in which companies operate. At one extreme they can imply little more than a commitment to a public relations exercise or the company taking a public affairs position on an issue. At the other extreme these big ideas represent highly strategic decisions to reposition a company and its products and services in new relationship to the systems of production and consumption within which those products/services fit.

Responsibility and sustainability continue to provide the ground for many competing and contested concepts and practices, few of which have been referenced against the basic principles of the Brundtland Commission’s (1987) and their seminal understanding of sustainable development. In the 27 years since the Brundtland Commission Report (1987) first articulated the rationale and principles for sustainable social and economic development a plethora of concepts have been advanced by academics and practitioners that provide an armoury of ideas, tools and actions by which companies can contribute to sustainability. These have included a range of concepts and the practices that follow from them such as the triple-bottom line (Elkington 1994), eco-efficiency (DeSimone et al. 1997), industrial ecology (Frosch 1995), base of the pyramid (Hart, REF), environmental stewardship (Cargill 2012) or, creating shared value (Porter and Kramer 2011; Nestlé 2010). Some companies associate strongly with these concepts while some do not make use of these concepts at all.

Unilever, for example, has interpreted its contribution to sustainability in terms of growing its business by producing products with social value while taking strides to reduce the main environmental impacts of those products by given amounts (Unilever 2014). It sets out to do this by seeking out new business opportunities for innovative products and services that have less environmental impact. And by persuading customers to behave differently (Unilever 2014). The company identifies this approach because it recognizes that the environmental impacts of the fast moving consumer goods it sells mostly arise during their use by consumers and not during their manufacture.

Unilever is among a rather small group of companies that have acknowledged that sustainability is first and foremost defined by a state of social and economic development that operates within the environmental limits or carrying capacity of the planet. Managers in companies that take this view recognize that while they are economic agents whose role is to help their companies succeed as profit seeking organizations at the same time they are concerned about how their current and future products and services contribute to the sustainability or otherwise of the social and economic systems in which they operate. This position raises fundamental questions about how a company creates, captures and distributes value whilst also giving consideration to the value that is often destroyed through the sourcing, production and use of those products.

There are other notable examples of companies that have subscribed to this broader view of sustainable (economic and social) development. In the early 1990s Ontario Hydro, did not define sustainability in terms of the ‘company’ or the ‘company and its supply-chain’, rather it set out to devise a strategy for the sustainability of the system of energy development and use in the province of Ontario, Canada (Roome and Bergin 2006). The ambition of the strategy was to reshape the company’s actions and to influence the work of other actors in the energy system of the province of Ontario.

Companies that look at revising the portfolio of products and services they provide often make use of some key concepts that help them to rethink the way their company might contribute to systems change toward sustainability. These concepts include the idea of ‘closed-loop production and consumption systems’, the implementation of practices around ‘cradle-to-cradle’ thinking (McDonough and Braungart 2002) or by drawing on the principles of The Natural Step (Robert et al. 1997).

This chapter focuses on the case of Umicore – a Belgium company that sought to reinvent its approach to business as a way to contribute to sustainable development. At the beginning of the case Umicore was a conventional materials company that sourced metal ores mined in Africa, that were transported and processed in Belgium and other sites, then to be manufactured into products that were sold for applications around the World. Umicore’s operations were based on the idea of material through-put – an approach that has dominated much industrial activity over the last 150 years. In this model the company’s financial performance accompanies the sale of more and more products while costs are controlled.

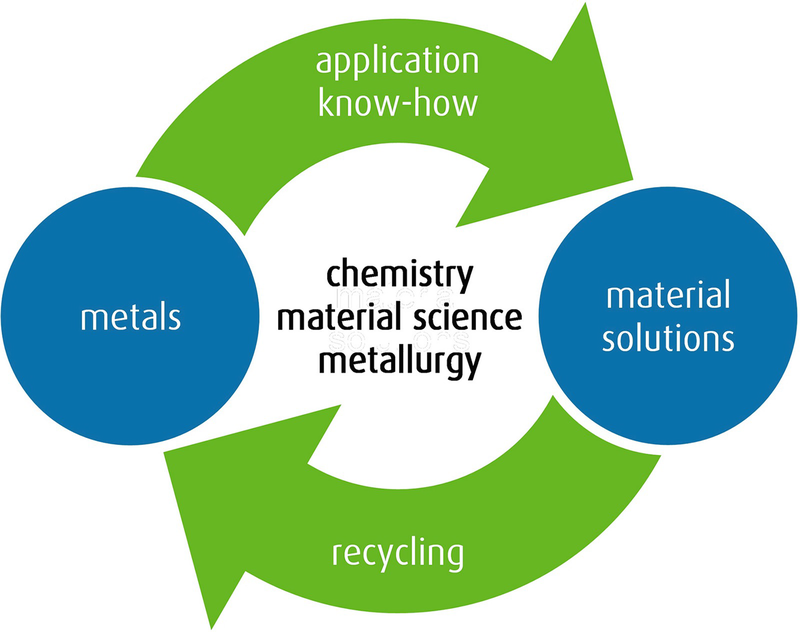

For reasons discussed later in the chapter, senior managers at Umicore determined that the future lay in positioning the company at the centre of a closed material loop, where materials, recovered at the end of existing uses, would be reprocessed and manufactured into products that were then used in areas of the economy that are springing up in response to different environmental challenges. In this new approach success would depend on the company’s ability to source, process, remanufacture, sell and then recover material. Success would also be determined by the ability to manage the transformation of the company from its focus original approach based on throughput to this circular material process.

This chapter does not examine the validity of the claims made for closed loop production-consumption systems as a contribution to sustainable development rather the aim is to describe the process of transformative change that took place at Umicore. The chapter pinpoints the main internal and external factors that drove this process, and identifies the internal forces that enabled actors in the company to bring about that change. In particularly it focuses on the roles and the beliefs held by internal change agents who lead the process of change.

The overall objective of the chapter is to inform our understanding of the processes of organizational change that contribute to this type of strategic transformation: An understanding that can contribute to theory as well as to practice.

To this end the chapter is divided into four main sections. Section “Case Method” provides a brief account of the methods used to collect data and the access to the company. Section “Introduction to Umicore and the Case” provides a brief introduction to Umicore as a company. It then provides a narrative account of change process at Umicore over the 19 years covered by the case. Section “Economic Restructuring – The Industrial Plan” discusses the process and the roles and beliefs of those responsible for the change process that is described in light of ideas from theory. The chapter ends with some concluding remarks.

Case Method

A case study approach was used to gain insight of the change process at Umicore. Case studies are the preferred method to use when “how” or “why” questions are being posed, when the investigator has little control over events, and the focus is on a contemporary phenomenon within a real-life context (Yin 2009). Case study research is also held to be particularly appropriate when the boundary between the phenomenon under investigation and its social context is blurred (Yin 2009). We assumed this was the situation as our focus was on a process of change that involved the organization interacting with its wider social and economic context. The case deals with past and recent processes of change over a long period. In that way the past provides a context to the present, and the present unfolds and shapes the future. No other method seemed appropriate given the extended time period of the case. The case qualifies as a reconstructed longitudinal case which according to Yin (2009), is best studied in a single-case study,

A qualitative approach enabled account to be taken of Umicore’s changing context. In addition a sensemaking approach (Basu and Palazzo 2008) was used to provide insight into how people involved in the case thought, spoke and behaved in relation to the concepts of responsibility and sustainability: As this would help to understand how these ideas influenced the strategic change at Umicore.

Data for the case were collected in two stages: first through desk research based on documents published by and about Umicore. This was followed by the collection of primary data gained through semi-structured interviews with key informants who worked for, or who had worked for, Umicore during the period of the case.

The desk research made use of material from the internet published by Umicore, from the press coverage of the company and visits to Umicore. This material was used to validate evidence from other sources. It was recognized that most of these documents were written for some specific purpose and specific audiences other than the case study reported here.

Interviews were crucial to the construct of the case study. Interviews took the form of guided conversations rather than structured enquiries. As a result of the documentary analysis six key people were identified as interviewees. The interviews began with Guy Ethier (current Vice-President Environment, Health and Safety, with Umicore since 2001), Moniek Delvou (Corporate Communications Director from 1999 to 2003) and Marc Dolfyn (Corporate Human Resources Director, with Umicore since 2003). These interviews provided a better knowledge of the transformation at Umicore. They were then followed by interviews with the three CEO’s that had led Umicore over the period of the case – Marc Grynberg (current CEO, and with Umicore since 1996), Karel Vinck (former CEO and former Chairman of Umicore, 1994–2008) and Thomas Leysen (former CEO and current Chairman, with Umicore since 1989).

A short list of key questions was created for each interviewee. The interviews were conducted in an open-ended way but following a certain set of questions derived from the questions guideline. Attention was given to the advice by Yin (2009) that “specific questions must be carefully worded, so that the interviewer appears genuinely naïve about the topic and allows the interviewee to provide a fresh commentary about it” (Yin 2009).

The material from these interviews was used to construct and label the phases in the change process that were used to structure the case narrative. Because the interviewees could be subject to the common problems of perceptual bias, poor recall, or poor and inaccurate articulation, the accounts of the respondents were cross-checked for consistency.

Interviews lasted about 45–60 min each. All interviews except one were done in English, and were recorded with the permission of the interviewer. All recorded interviews were transcribed and retained. One interview could not be recorded because of background noise. In this case notes were taken manually and transcribed afterwards. This interview was done in Dutch, as preferred by the interviewee.

While the case itself cannot be replicated the following controls were used to ensure the reliability of the data that was collected to construct the narrative of Umicore (a) multiple sources of evidence were used to develop converging lines of inquiry and to provide confirmation of the data, (b) a case study database was developed and stored which provides a collection of evidence separate and distinctive from the final case study report, and (c) a chain of evidence was sought (Yin 2009). This chain of evidence explicitly links the questions asked, the data collected and the conclusions drawn. “The principle is to allow an external observer – in this situation, the reader of the case study – to follow the derivation of any evidence from initial research questions to ultimate case study conclusions” (Yin 2009).

Data from the documentary review and interviews were analysed and compared. The data comprised a mixture of qualitative and quantitative information, with an emphasis on the written and spoken word. Given the explorative nature of the research and our concern to understand how approaches to corporate responsibility and sustainability were understood and developed, we did not apply specific analytical techniques to the raw material.

Interviews were transcribed and compared with documents and archival records with the intent to develop an authentic record of how CSR/sustainability was understood and communicated in the company. Where possible the case was written to include the images, materials and language that senior managers used to describe the CSR strategy and practices in their business. Indeed, managers were explicitly asked to describe how the leaders proceeded to the organizational change. A final draft of the case was sent to Thomas Leysen, Chairman of Umicore, and to Bart Crols, Corporate Communication manager, who assessed the historical correctness of the data.

We acknowledge that our findings cannot be generalized. However, that was not the purpose of the study. The single case study provides an in-depth analysis of organizational change around CSR and sustainable development and the contribution of individuals and groups to that change process.

Introduction to Umicore and the Case

Introduction

Umicore has a history going back 200 years. Today’s materials-technology company is the outcome of a history of mergers, acquisitions and transformations by companies in the mining and refining industry. Umicore has only recently evolved into a materials-technology provider. Moreover Umicore does not have an unblemished past. Changing company practices and social expectations led to a series of scandals that stained the company’s reputation. These include: the extremely hard living and working conditions of employees in the Congo, seizure of uranium by the Germans and then deliveries of the same material to the Americans during WWII and – most importantly – environmental pollution and associated health concerns among employees and neighbours surrounding sites where metal ores were processed. At the beginning of the 1990s, Union Minière – the former name of Umicore – was also coping with extremely bad financial results – the company was almost bankrupt.

Today Umicore describes itself as a materials group that focuses on clean technologies. It employs more than 13,000 people. It continues to deliver outstanding financial results and regularly outperforms the BEL20. On top of that, it has been externally acknowledged as a flagship of sustainability, receiving praise for its contribution to sustainable development. It has won multiple awards in this area. 1 It is a member of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development2 and is included in the FTSE4Good Index.3 In 2014 the company was ranked 9th in The Global 100 list for clean capitalism.4

In its current form, group Umicore operates through four business areas: Advanced Materials, Precious Metals Products and Catalysts, Precious Metals Services and Zinc Specialties. Each business area is divided into market-focused business units.

The Advanced Materials business area produces high-purity metals, alloys, compounds and engineered products for a range of advanced applications. The main materials used are cobalt, germanium and nickel. The business area is composed of three business units: cobalt and specialty materials, electro-optic materials and thin film products. Furthermore, the advanced materials business group comprises a 40% shareholding in Element Six Abrasives, which produces synthetic diamonds and abrasive materials for use in industrial tools.

The Advanced Materials business area makes products such as rechargeable battery materials and germanium wafers for solar cells.

The Precious Metals Products and Catalysts business area produces a range of complex functional materials based on precious metals and its expertise in technology platforms such as catalysis and surface technology. The business is organized in five business units: automotive catalysts, catalyst technologies, jewellery and electroplating, platinum engineered materials and technical materials. This business group produces products such as catalysts used in automotive emission systems.

The Precious Metals Services business area is the world market leader in recycling complex waste containing precious and other non-ferrous metals. Its core business is to provide refining and recycling services to an international customer base. It is divided into three business units: precious metals refining, precious metals management and battery recycling. The Precious Metals Services business group offers services such as recycling.

The Zinc Specialties business area develops zinc-based materials for a wide variety of applications. Zinc Specialties is organized around three business units: zinc chemicals, building products and zinc battery materials. The Zincs Specialties business area produces, for instance, materials for building applications such as roofing.

Umicore generates approximately 50% of its revenues and spends approximately 80% of its research and development budget in the area of clean technology. This includes areas such as emission control catalysts, fuel cells, materials for rechargeable batteries, photovoltaic systems, and precious metals recycling. Research & development for clean and sustainable technologies is mainly done in Olen. There are also Business Unit dedicated research centres in Germany, Japan, Canada, France and Liechtenstein.

Umicore articulates the group’s goal and mission in the form of the ‘Umicore Way’: it states “Umicore’s overriding goal of sustainable value creation is based on the ambition to develop, produce and recycle materials in a way that fulfils its mission: materials for a better life.”

Umicore recorded a turnover of € 6.9 billion in 2009, with an EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes) margin of 8,9% and a ROCE (Return On Capital Employed) of 8,2%. Umicore shares are listed on Euronext Brussels with 100% free float. Umicore is part of the BEL 20, the benchmark stock market index of Euronext Brussels, and does not have a reference shareholder.

At end of 2009, Umicore had 13.720 employees, located in 37 countries on 5 continents, in 79 production sites and 48 other sites. More than half of Umicore’s employees were working in Umicore’s largest production centres in Belgium. The other main centres of employment were 2.963 people in Germany 2.296 and 2.225 in China.

Umicore has a dual governance structure consisting of a supervisory Board of Directors and an Executive Committee. The Board of Directors, consists of at least six members appointed by the Shareholders’ Meeting, Their normal term of office is 4 years, although re-election is possible. At the end of the case the Board of Directors consisted of ten members: nine non-executive directors and one executive director. On 31 December 2009, six of the ten directors were independent within the definition of independence defined by Umicore’s Corporate Governance Charter.

Thomas Leysen had been the Chairman of Umicore since November 2008 after serving as Chief Executive Officer from 2000 to 2008. In addition he has numerous other functions on the board of other companies. Marc Grynberg was Chief Executive Officer of Umicore from November 2008, succeeding Thomas Leysen. He joined Umicore in 1996 as Group Controller. He was Umicore’s CFO from 2000 until 2006, after which he became the head of the Group’s Automotive Catalysts business unit until his appointment as Chief Executive Officer. Marc Grynberg holds a Commercial Engineering degree from the University of Brussels (Ecole de Commerce Solvay). Prior to joining Umicore he worked for DuPont de Nemours in Brussels and Geneva.

The Executive Committee is composed of at least four members. It is chaired by the Chief Executive Officer, who is appointed by the Board of Directors. The Board of Directors appoints the other members of the Executive Committee upon recommendation of the Nomination and Remuneration Committee.

Senior Management is composed of representatives of the four business areas, as well as corporate vice-presidents in the areas of R&D, legal affairs, and Environment, Health and Safety (EHS).

Closed loop (Source: Umicore)

we are a company that plays a major role in providing products and services that are enablers of a more sustainable future.

While our products can make a positive difference in the world we are also committed to ensuring our operations are run in such a way as to minimize our environmental footprint. We also undertake to be the best possible employer and neighbour and to adopt the best standards of business ethics and governance both within Umicore and through our supply chain. (Umicore 2014)

The Case

History of mergers, acquisitions and transformations (Source: Umicore)

The oldest of Umicore’s predecessor companies, Vieille-Montagne was created in 1805. Another predecessor, Union Minière du Haut Katanga (UMHK), started its activities in 1906. UMHK mined the rich mineral resources of Belgium’s former colony of the Congo (copper, cobalt, tin and precious metals). UMHK expanded rapidly: between 1913 and 1917 production quadrupled because UMHK supplied the basic materials for weapons manufacture (van Caloen 2001). Non-ferrous metals were transported to be processed in Europe – for instance at Metallurgie Hoboken- Overpelt, which would later merge with UMHK. The most prosperous years for UMHK were the post-WWII years: in 1955, UMHK employed 21.000 workers and 1.915 European agents in Congo. After the Zairian government nationalized UMHK’s assets in 1968, Union Minière set out to develop new mining activities to feed its refining capacity. It eventually became a sub-holding company of the Société Générale de Belgique.

Historically, Union Minière was a financially well performing company albeit in a cyclical industry. However, after the company left the Congo as a result of the nationalization of the mines in 1968, it had to invest in new mines. These investment decisions were unsound leading to a very bad financial situation in the beginning of the 1990s on top of the cyclical nature of the business.

In 1989, 88,2% of the shares of Union Minière belonged to the Belgian conglomerate Société Générale de Belgique. This company had appointed a French CEO, Jean- Pierre Rodier.

Umicore has had to deal with serious social and environmental concerns. First of all, UMHK employed an increasing number of African workers in the beginning of the twentieth century: 8.500 in 1919, 17.200 in 1929 (Brion and Moreau 2006). Such an expansion in the sparsely populated Katanga province obliged the company to recruit massively outside Katanga, in particular in Rhodesia and in other Congolese provinces. Public opinion in Belgium was not always in favour of recruiting workers hundreds of kilometres outside their hometown. In addition, the living conditions of the African workforce in Katanga were very harsh. Second, Union Minière was the principal producer of uranium when WWII started. During the war, the German government seized some 2.000 tons of uranate. The American government used uranium supplied by Union Minière to create the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Third, as public awareness of environmental issues increased in the 1980s and 1990s Union Minière started to realize it had to cope with historical legacy of pollution at its production sites in Belgium and elsewhere. This was the most important problem Union Minière had to deal with.

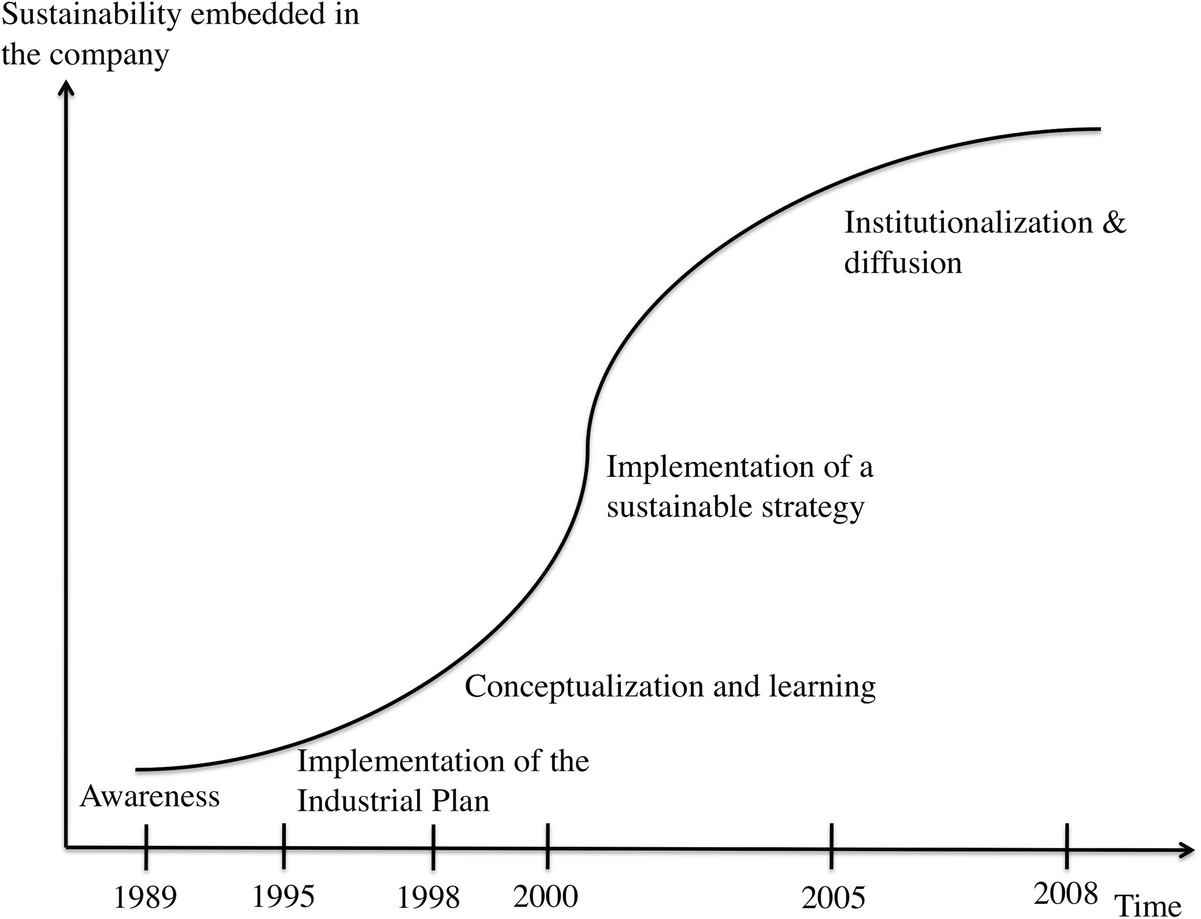

Five stages. Increasing awareness of financial and reputational/environmental problems

At the beginning of the 1990s Union Minière was well-known for its technical competence, however the company was dealing with two principal problems. The financial viability of the company and a series of reputational problems then linked to environmental pollution. Although these problems had been developing for some time, in the early 1990s, there was a growing public and political concern and an increasing awareness that it was time they were addressed.

Union Minière was aware of both problems, but it gave priority to resolving its financial problems as it was held that unless this was solved, the company couldn’t survive and the environmental problems would not be addressed.

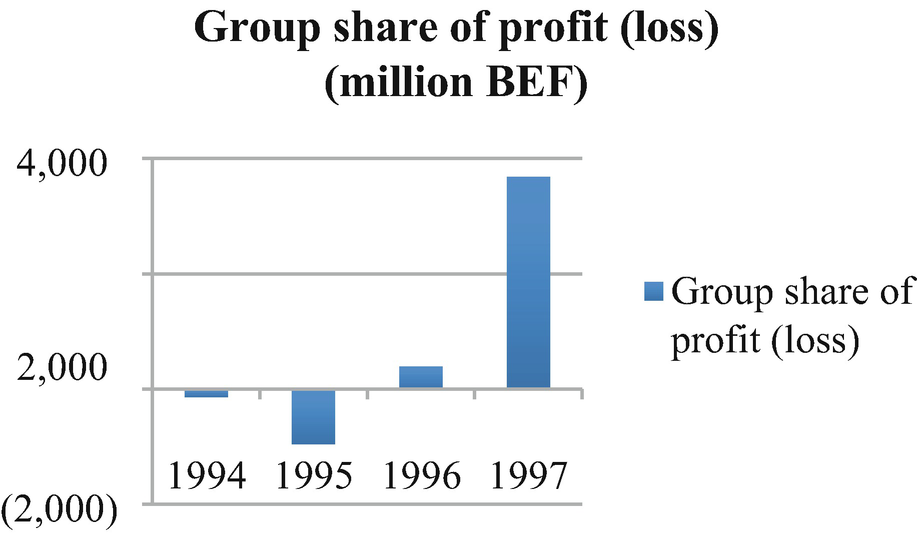

Financial problems resulted from the bad investments in the 1970s and the 1980s when the company left the Congo and invested in new mines, for instance in Canada, as well as a project to prospect for metals on the bottom of the sea. These investments generated poor returns and there were few reserves left. Société Générale, which held almost 50% of the shares in Union Minière, realized the situation at Union Miniere needed dramatic change.

Etienne Davignon, then Chairman of Union Minière, contacted Karel Vinck, then the CEO of Bekaert, to help Union Minière survive the financial situation. Etienne Davignon did not play a significant role in the operational and financial turnaround of the company but he became involved with sustainability issues. From 1998, he hosted the first Advisory Board of CSR Europe and became one of the leaders of this initiative. In 2001, Etienne Davignon contributed to the establishment of the European Academy of Business and Society, a multi-stakeholder platform on CSR.

Marc Grynberg, the CEO of Umicore at the time of the case, summarizes the situation as follows: “In the mid-1990s Union Minière was in a really bad shape with fairly outdated industrial assets, lousy profitability and not a very strong positioning on the market place.”

Karel Vinck had a reputation as a turn-around manager. He had transformed the company Eternit in the 1980s and was then restructuring Bekaert. He joined Union Minière at the end of 1994. Karel Vinck thinks he was appointed because his experiences at Eternit and Bekaert, and his excellent relationship with the workers’ unions.

The company was fully aware of its environmental problems as its sites had been polluting for over 100 years. Early in 1992 the company recognized that the environment was a major strategic issue. It was decided to establish a central environment division for the whole Union Minière group to provide an organizational structure for the management of environmental issues in the company. One of the first actions of the division was to develop an Environment Charter. It was drafted by the corporate environment group, after much internal discussion until the management committee agreed that it covered all the essential values Union Minière would like to respect.

Economic Restructuring: The Industrial Plan

When Karel Vinck’s took over as CEO at the end of 1994, he launched a restructuring plan for the period 1995–1998. He involved top management and used a mixture of a top-down and a bottom-up approaches to implement the plan. It was top-down in the sense that he was guided the operational aspects of the plans, had the final word on decisions and took full responsibility. On the other hand, it was bottom-up because Karel Vinck considered that he could not make the new strategy work from his office but instead he had to be in contact with the internal mood of the company and communicate in informal ways with the workforce. In other words, this process of implementation was formal (e.g. Board decisions) as well as informal (e.g. chatting with the employees on the work floor). Karel Vinck had relied on these skills and this combined approach in previous restructuring and believed it is effectiveness.

The plan was based on investment of BEF 22 billion. (40,3399 BEF = 1€) over the period 1995–1998 to finance the gradual replacement of refining activities (e.g. zinc, copper) with new (higher margin) industrial activities based on technologies that were then available to the company. Union Minière already had a number of product applications available, such as materials for batteries and solar cells. The Industrial Plan focused on developing these areas further. Special emphasis was placed on innovation. This was given greater profile when Karel Vinck created a single global R&D centre in Olen, to replace the R&D activities that were previously dispersed over three different sites. In addition the Industrial Plan involved cost-cutting, requiring some 2.000 jobs to be lost (about 15% of the work force), accompanied by the sale of divisions with lower margins. Only those divisions in which Union Minière could become a world leader were retained.

Karel Vinck involve the rest of the management as closely as possible in his decisions and in 1995–1996, Union Minière adopted a Company Charter, as a first attempt to define the objectives that would bind the company together. This included commitments to respect the legal environment and human rights, to reject fraud and corruption, to show openness and transparency, and to respect the environment everywhere it operates. The company charter followed after the environment charter and included some of it principles.

Evolution of group share of profit (Source: Umicore)

In terms of environmental problems and reputation Karel Vinck, said you “couldn’t have dreamed of having the political support [sic for the company] with an image that would have been that of the worst polluting company in Belgium”. Hence, Union Minière had to take measures and dedicate funds to its environmental problems and it had to communicate its new approach both internally and to the external world.

The reactive environmental action was set in place through an agreement Union Minière and OVAM under the supervision of the Minister of the Environment in December 1997. (OVAM stands for Openbare Afvalstoffenmaatschappij voor het Vlaams Gewest – Public Waste Agency of Flanders). This agreement, for a period of 10 years, covered the investigation of pollution sites and soil remediation to remove all the serious risks arising from the historical pollution at Union Minière’s Flemish production sites. The agreement was entered into under the wider scope of a Flemish Soil Remediation Decree which came into force 22nd February 1995. Union Minière could not afford to have further environmental problems and compliance with the environmental regulations was a “must do”.

Conceptualization and Learning: The First Formulation of a Strategic Approach to Responsibility

Once the Industrial Plan began to yield results the company started to look for ideas to resolve the reputational problems that followed its environmental legacy as this would that dog its future. People inside the company were encouraged to start thinking about responses that would help resolve the future financial position of the company together with its reputational problems. After all, the company had experienced financial and environmental problems because of the way it operated and the thought was that those problems might be resolved through the way it operated in the future.

However, this meant addressing the raison d’être for the emerging company. Thomas Leysen remembers three principal ideas: “First of all we wanted to be a company that was active in fields where it could make a difference through technology. Secondly we wanted to be active in fields where we could have leadership positions on a global basis. Thirdly we wanted to integrate the sustainable development thinking, not only in our operations, but also in our strategy and that this would be a core part of what we wanted to be as a company and this applied notably to a very large commitment to recycling. We saw this as a possibility for us to differentiate ourselves and to make a real contribution.” Moreover, the company wanted to move from pollution reduction to pollution prevention and through that redesign itself and its operations to avoid pollution as much as possible. These principles informed the vision for the company that was emerging. Some key concepts were then identified through which to drive towards that emerging vision – these concepts were to become a closed loop company with a commitment to environment and clean technology applications, where the environment was an opportunity not a constraint.

The operational practices needed to make these concepts a reality developed gradually. In 1998 Thomas Leysen took over the lead in the Cobalt and Specialty Materials business unit. He knew the company very well as he had held different positions within Union Minière during the previous 10 years. Together with Karel Vinck he decided to test the new idea of being a closed loop company beginning with the Cobalt and Specialty Materials business group. The two men worked closely together building on Karel Vinck’s experience gained outside the company and Thomas Leysen long career with Union Minière. “We really understood each other and respected each other and I guess the success of Umicore today is linked to the fact that the CEO and the Chairman had an excellent relationship” believes Karel Vinck.

The Cobalt and Specialty Materials business group provided Thomas Leysen with the test bed where he could explore and develop the closed loop approach on a small scale. This was based on the recycling and recovery of used material that were then processed into new products. In addition Thomas Leysen tried to proactively manage the company’s overall environmental position by preparing the business for upcoming legislation, coming trends, and how it should be ahead of the curve on the environmental side. This would require close contact with employees to encourage their engagement in change that was necessary from these developments.

- 1.

Basic level or compliance level: The main goal is to achieve compliance with regulatory and specific permit requirements;

- 2.

Medium level or ISO 14001 certifiable: In addition to the basic level, focuses on implementing a systematic management system to promote continuous improvement of environmental performance;

- 3.

High level or business excellence level: In addition to the medium level, the key goals are the implementation of an EFQM (European Foundation for Quality Management) model and the introduction of a benchmarking with internal and external partners.

The management and reporting systems were subject to the same type of testing and learning as found in the development of the closed loop approach to business. At this stage the reporting system was restricted to Umicore’s business units or wholly-owned industrial sites within the European Union. Sites were requested to formulate objectives, state which environmental management level they were aiming for and when it would likely be achieved. These decisions were left to the business unit or the site management to determine.

A structured, standardize method was laid down at the central level in order to enable consistent reporting of each site’s operational environmental performance. This enabled the company to provide an overall, transparent and structured assessment of the Union Minière’s Group’s environmental performance. This was accompanied by a set of Environmental Performance Indicators (EPIs) that were divided in five groups: input indicators, output indicators, environmental performance management indicators, societal indicators, and financial indicators. This procedure was developed to prepare the company for the introduction of a more general approach to the implementation of management systems.

The development of the management system meant an environment section could be included in the 1998 annual report. This described the Company Charter and the ISO 14001 certification that applied to the Union Minière plants. It led to the first stand-alone environmental report published in 2000 related to fiscal year 1999. Through this means the company began to increase the openness of its relationships with governments, non-governmental organizations, financial stakeholders, the community and the media; and inside the company, to provide the foundation for a coherent management system, based on a set of measurable environmental performance indicators. This made clear to all employees that the environmental performance of the company would be taken seriously and any failure would be public.

- 1.

Regarding the past: to find practical solutions to the issues of historic soil and groundwater pollution, resulting from long industrial history;

- 2.

Regarding the present: to improve production process in terms of emissions and waste management;

- 3.

Regarding the future: to develop products that are not only environmentally safe but also “ahead of the time” by full collaboration and partnership with customers.

All plants – inside the European Union – were required to meet the company’s environmental standards, as well as those established by law. In some cases, Union Minière’s own requirements were more stringent than current regulations. The report was verified by the company ERM-CVS7.

Highlights of the first environmental report were that metals emissions into the atmosphere and water had halved over the past 5 years and that Union Minière had increased the proportion of recycled products in its total feedstock. At the time, recycled products accounted for 28% of total raw materials, which was already a higher percentage than normal for the sector as a whole.

At this time Union Minière began to adapt its “corporate vocabulary” so that it was better aligned with the new vision it had begun to conceptualize. In its Annual Report 1999, the company stated: “We believe that successful companies get things right for their customers, employees, suppliers, shareholders and communities. Financial health not only depends on extracting value, but also on creating value for all the stakeholders. Sustainability driven companies achieve their business goals by integrating economic, environmental and social growth opportunities into their business strategies.”

The company continued to promote the importance of working with employees on organizational change and supported this with their first employee survey. This survey has subsequently been repeated every 3 years. The company also sought out 7 ERM Certification and Verification Services (ERM CVS) is the worldwide environment, health and safety certification and verification business of the ERM Group, one of the world’s largest providers of professional EHS services.

innovative ideas and in 1998 a Venture Unit was launched to create a nurturing environment to develop and test new ideas until they were ready to be absorbed by one of the existing business units or to provide the basis for a new business unit.

The Venture Unit acted as an incubator for ideas for products and product application.

During the testing and learning phase, the initial scope of the portfolio was restricted to ideas coming from inside the Group, in particular from the Advanced Materials business group. Although the company invested in some other start-ups by means of venture capital funds to create businesses or to give the chance to test new businesses. The final step in this testing and learning period was the creation of a new slogan for the company in 1999. That year, a new communications director was appointed, Moniek Delvou. She had a proven track record in the area of communications. One of the first things achieved after joining Umicore in 1999 was a change in the slogan of the company. Up to that time Union Minière’s slogan was “Of metals and men” and its logo consisted of five men in different metals.

The new communication director noted that the logo and slogan did not describe what the company was now doing. She believed it would be better to have a slogan explaining putting the company and its products into context. One day, when sitting in Thomas Leysen’s office the idea came forward of “Materials for a better life”. The slogan for the company was changed from one day to another. Although the company continued to use its old slogan externally it was rolled-out in a meeting with senior executives without complaint. In fact there were no reactions, either positive or negative.

“Materials for a better life” was then communicated to the outside world signalling the completion of the ambitious repositioning of the company that was initiated in 1995. As recognition for its growing commitment to sustainable development and the incorporation of responsible economic, environmental and social behaviour into its business strategy, Union Minière was included in the Dow Jones Sustainability Group Index in 2000. This Index claims to track the performance of the top 10% leading sustainability-driven companies worldwide.

Implementation and Roll-Out of Strategy

By June 2000, Union Minière was beginning to be recognized as a different company but it had not yet fully completed the process of change. It was now financially sound and it had tested the new concepts that might link its future economic and environmental performance, it had promoted employee engagement and innovation. It had put a management and reporting system in place. It was now time to scale-up and implement that approach on a company-wide basis.

Karel Vinck felt that it was time to stand down as CEO. He also believed that a CEO shouldn’t stay more than 8–10 years at the top of a company for three reasons: “First of all, the business environment is changing and as a leader, you never adapt the way you should to this changing environment and its new challenges. Second, after 8 to 10 years you start to react and take decisions instinctively. Third, you get emotionally involved with the workers.” His designated replacement as CEO was Thomas Leysen while he would become Chairman of the company. In addition to his key role in developing and testing the new concepts – closed loop materials with clean technology applications – Thomas Leysen had been in charge of the strategy department and the copper and precious metals business group. This gave him the necessary credibility to become the CEO of the company at the age of 39.

Thomas Leysen was confident in taking this role and setting the direction for the company. When he became CEO, he decided to change the name of the company to communicate its new vision and the new approach to business more clearly. Union Minière wanted to develop its approach to the environment and to create an excellent working environment for employees especially including health and safety. In the case of the environment this was still seen in terms of three responsibilities: past, present and future. But these three axes of responsibility were slightly adapted: the past now meant coming clean over the historical pollution problems caused by the company, the present axis represented continuous improvement of its environmental performance, and the future axis focused on the precious metals and internationalization. Special attention was given to improving the communication of these pillars to the outside world. And matching that communication to action.

Moniek Delvou, the communications director who had already triggered the change of the slogan, received a mandate from the Board to change the name of the company, as it was the moment to signal Union Minière’s new direction and identity. Research on the opinions of employees, journalists, politicians, analysts and members of the general public came to the view that the name ‘Union Minière’ was associated with heavy industry and a colonial past. More positively it was associated with the competences of its engineers. It was decided to change the name while at the same time keeping a reminder of the old name.

Employees and others were invited to suggest names. Some 2000 suggestions were received. The names were reviewed by a small team presided over by Thomas Leysen leading to the choice of “Umicore”. The selection filters were based on the link with the past, linguistic meaning, legality and Internet availability and the future. “The reason why we took finally Umicore was because of the core. It was unique: there was Union Minière – Umi was still there, and the ‘core’ meant that we wanted to go back to the core.” explains Moniek Delvou. Beyond that the metals and materials created by Umicore were seen to be at the core of products essential to everyday life with new high technology applications. The company’s commitment to contribute to sustainable development, was as a pioneer in recycling and environmentally responsible products and processes, with environmental sector applications. The consonant-vowel structure made it easy to pronounce in many of the world’s languages.

The New Umicore (Source: Umicore)

Creation of the logo (Source: Umicore)

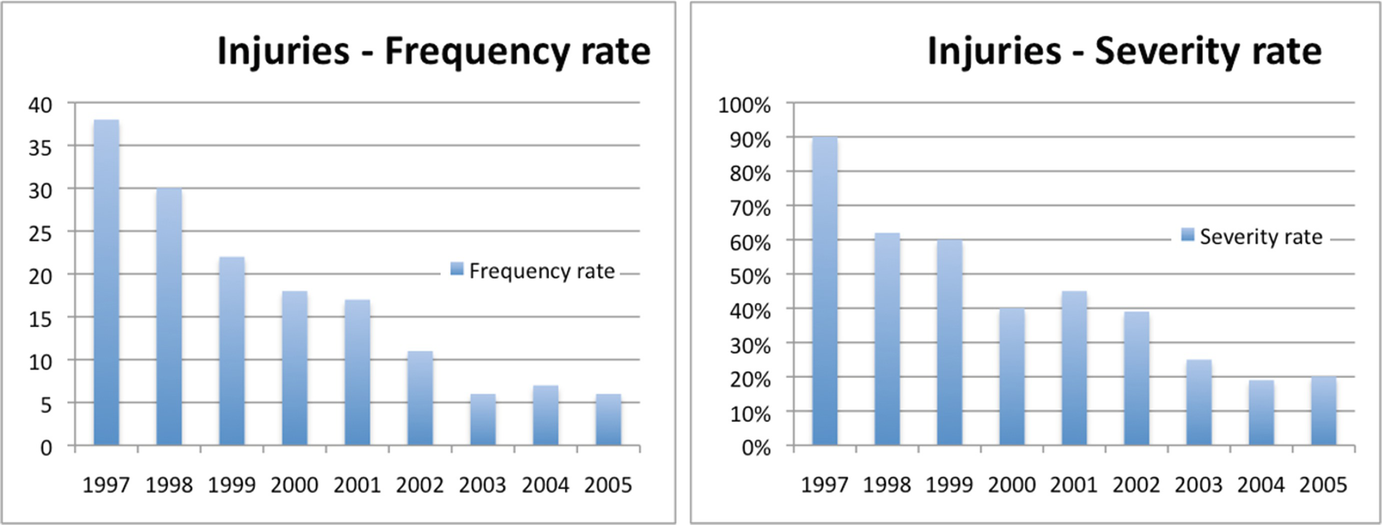

However, those leading the transformation knew that a new name and logo were not sufficient to bring about wholesale change in the company, they merely reinforced the direction of change. Delivering on the new vision would require profound change in the way employees and others saw the company. So from 2000–2005 Umicore focused on change that emphasized employees and the environment.

Umicore repeated the employee survey in 2001. With a 70% employee participation the survey showed there were clear improvements in 11 out of the 15 reporting categories compared with the 1998 survey. Organizing this survey on a regular basis brought the company closer to its stated ambition of involving people more closely in their work and workplace by communicating openly and frequently and by giving everyone a say in how their work is organized.

Injuries frequency and severity rate 1997–2005 (Source: Erzmetall 60 2007 No. 3)

Umicore was now in a position to address its commitment to resolve its environmental legacy and to shape the future. Umicore proceeded to two site remediation programs to resolve issues from the past: first, a clean-up of a smaller plant in Bulgaria, and second, the signing of an agreement with the OVAM for the clean-up of all of its plants in Flanders.

Umicore’s internationalization strategy led it to acquire plants outside Belgium. It bought a plant at Pirdop, Bulgaria with a commitment to remediate the historical pollution created by the previous owner. US$25 million was spent in 2003 on the remediation of the significant pollution. This was undertaken by the company in collaboration with the World Bank and the Bulgarian authorities. This innovative collaboration gained recognition, not only in Bulgaria but also abroad. It received the Belgian Environmental Prize 2003–2004 in the category “international partnership for sustainable development” from the Belgian Minister of Environment.

In April 2004, Umicore then signed an agreement with the Flemish Government and the Flemish Waste Authority (OVAM) to address all remaining issues following the 1997 Agreement over Umicore’s plants in Flanders. This agreement covered the remediation of soil and groundwater contamination in and around Umicore’s main Flemish sites: Balen, Hoboken, Olen and Overpelt. In signing this agreement, Umicore not only sought to tackle its historical environmental legacy but also to demonstrate its commitment towards the local community.

- 1.

Concrete guidance for the remediation of the Umicore sites and the immediate surroundings;

- 2.

Remediation of the wider surroundings (a radius of 9 km of each of the four main Flemish plants);

- 3.

Smooth procedures for the transfer of remediated land.

While the agreement covered a period of 15 years, Umicore stated that it was its ambition to carry out most of the remediation within the next 3 years.

The total budget agreed by Umicore was €77 million, from which €39 million were dedicated for the remediation of its plants and the surrounding residential areas over the coming 15 years, with a further €23 million to be spent to cover related operating costs. Additionally, a joint fund with the Flemish authorities was created, to which each party contributed €15 million over a period of 10 years, to be used to address identified risks in the areas outside the plants. The agreement with OVAM had no immediate impact on Umicore’s financial results for the period, as provisions had been built up in the financial statements of previous years.

In the same period beginning Umicore committed to eight environmental objectives that were to be achieved by the end of 2005. These were linked to the Environmental Performance Indicators (EPIs) developed during the testing and learning phase (1998–2000). By 2005, Umicore had registered an increase of the input of secondary (recycled) materials to more than 30%, a reduction of use of water of 20% and a reduction of emissions of metals from process sources by 50%. Furthermore, the limits on CO2 emissions imposed by international legislation was met and ISO 14001 certificates were obtained in the majority of the operational sites.

Although there were no direct rewards for plants that complied with the EPIs, the system works because site performance is published and the performance system was linked to objectives that follow from the company’s values. Umicore also committed to benchmark itself, through the employee survey, and to be in line with the Global Chemical Industry and Global High Performance Norm – a selection of companies combining good business performance and sound people management practice.

This phase was completed by the launch of two new projects in 2005: ‘Umicare’ and a Suppliers’ Code of Conduct. ‘Umicare’ encouraged business units to engage in projects, which benefited their local communities. The Code of Conduct for Suppliers detailed Umicore’s expectations from its suppliers in areas such as behaviour, environmental approach, employment or child labour. It states that the company seek business partners whose policies regarding ethical, social and environmental issues are consistent with these of held by Umicore. Special attention was paid to mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The internal audit team of Umicore conducts regular supplier audits in the DRC and Umicore committed to halt business with any company which was not able to demonstrate compliance with the code. Indeed companies have been removed from Umicore’s supplier list as a result of this audit process. In the case of minor infractions a plan to help improve the supplier’s operational practices can be agreed and followed-up. Umicore involved a number of NGOs and other external parties in formulating this approach.

The financial situation for Umicore was favourable when Thomas Leysen took over as CEO. The net result for 2000 of €136 million was almost twice the result of 1999. This resulted from a favourable dollar exchange rate and by the price of some metals, such as zinc as well as progress made in the transformation of the business. The divisions specializing in zinc, precious metals and specialty materials had impressive results. Thomas Leysen saw this as the moment to continue to change the orientation of the group towards products with higher value added, that provided solutions for the future. While the 1995–1998 Industrial Plan prioritized the refining activities. From 2000 on, part of the new investments would be dedicated to more sophisticated products.

In particular Umicore sought to consolidate its leadership in the recycling sector and to translate its expertise in recycling in the “precious metal” business unit to other business units dealing with advanced materials. This approach led to growth of the company through the organic growth that arose from the internal exchange of ideas between business units and through acquisitions in the area of advanced materials.

Organic growth was pursued through increased R&D spending. A Venture Unit was created dedicated to foster innovation around materials recycling and applications. A new initiative ‘Umagine’ was launched to run in parallel to the Venture Unit. At the same time Umicore increased its R&D spend and sought to establish a more embedded innovation culture that stood outside a central R&D facility.

70% of the total R&D budget was used to support the business plans of the individual business units. In these business plans economic performance and sustainability were important topics. The greater part of Umicore’s long-term research budget was directed towards ways the company could contribute to renewable energy solutions such as fuel cells and solar cells.

30% (the remainder of the R&D spend was centrally managed and primarily meant to support Umagine initiatives.

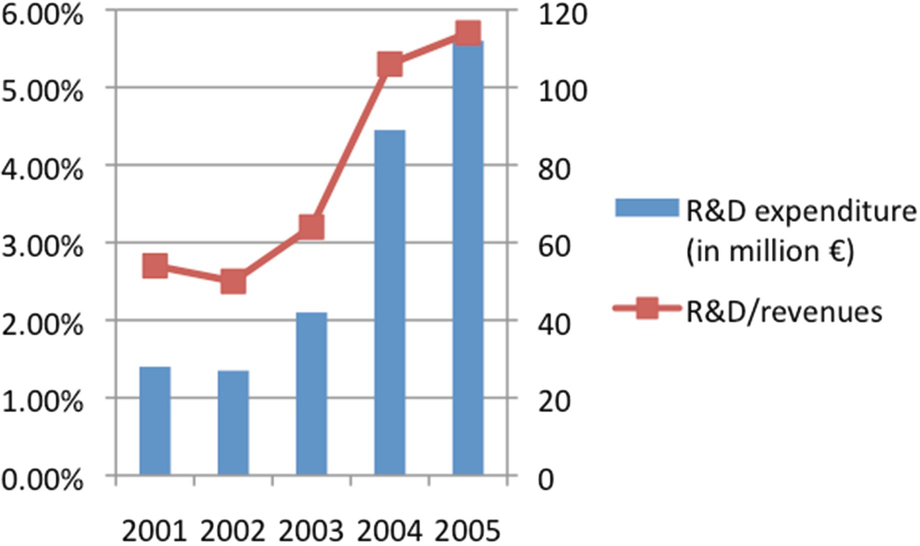

R&D expenditures 2001–2005 (Source: Umicore)

Umagine was designed to stimulate and foster innovation in Umicore from the bottom up, and in that way complementing the Venture Unit. People from different businesses of Umicore, were encouraged to work together with outside participants by interacting in ‘ideas labs’ around selected themes such as recycling and nano-technology. These highly interactive processes generated a wealth of ideas that were checked against criteria in line with Umicore’s overall strategy. These included parameters such as their business potential and sustainability. Gradually, Umagine and the Venture Unit became less needed as the company as a whole adopted a culture of innovation based on a team approach to the generation and testing of ideas. Thomas Leysen sought to stimulate this approach by opening up the company to ideas exchanged among colleagues, across the company and across it boundary. In this way the company culture evolved from a culture of ‘doing and complying’ to a culture of ‘learning and innovating’ where all employees were invited to participate.

The company also sought to consolidate its new approach through acquisitions and mergers. In July 2003 Umicore bought the “Precious Metals Group” (PMG), a subsidiary of the American company OMG for €643 million. It was the company’s largest acquisition until then.

PMG contributed new applications in the area of precious metals. It was an important producer of automobile catalysts and of a whole series of materials based on precious metals. It fitted well with Umicore’s slogan of ‘Materials for a better life’. Through the addition of PMG, Umicore mastered the entire life cycle of precious metals: collecting and pre-processing of recyclable waste, in particular of used automobile catalysts, refining end-of-life products and secondary industrial materials (resulting from foundry operations and refining of other metals), and fabrication of products designed for new uses. The acquisition of PMG also strengthened Umicore’s geographic presence in North and South America.

The integration process of PMG was a success. But the most difficult part of the acquisition was reconfiguring precious metal refining because of the overlap between refining at Umicore plant at Hoboken and the Hanau plant of PM. As the plant of Hoboken had the most advanced technology in the world for recycling, it was decided that the plant in Hoboken would undertake all the refining activities, whereas the plant in Hanau would concentrate on the other activities of the precious metals business unit. Integration of PMG significantly increased Umicore’s scientific knowledge and its applied technological know-how, with more than 500 people then active in this area.

From 2003 on, the copper business was organized in such a way that it could function as a stand-alone company. Umicore prepared this division for sale. In 2005, the copper operations were spun off into a new company, Cumerio, to enable Umicore to move ahead more swiftly in its evolution as a specialty materials business. Three plants were concerned: Olen (Belgium), Avellino (Italy) and Pirdop (Bulgaria).

By 2005, Umicore also decided to concentrate the strategic focus of its zinc division on the production and sale of zinc specialty products. This strategy reduced the output of commodity zinc and concentrated on the development of downstream zinc specialties activities.

Umicore paid special attention to its employees as part of its sustainable strategy, and hence established a new Human Resources Management Organization in line with the operational and cultural needs of the new Group in September 2003. Responsibilities for HR now largely rest with the HR functions at country or regional level while the corporate HR function guided the overall policy formulation, management development and HR networking.

All these changes in the business were supported by more transparent external communication, replacing Union Minière’s previous lack of transparency. But to do this the new Umicore had to develop its expertise and gear up the range of communication tools through continuous improvement. These included: the environment report, local site reports, press releases, open-door days and improved websites.

We do not just want to create value only for our shareholders, employees and customers but we also want to create value for society as a whole. We endeavour to achieve this by operating in an environmentally responsible manner and by delivering materials and services that are essential both for everyday life as well as for technological progress. (Umicore Annual Report 2010)

The Environment and Safety Report of 2001 extensively described Umicore’s product safety philosophy. It included a sound scientific approach to assess the hazards and the risks in using Umicore’s products. By then the tagline “Responsible towards future generations” indicated Umicore was comfortable to communicate the approach to sustainability it was developing and the report was expanded in breadth as well as depth. All the company’s sites reported on their performance in a report based on three main sections: the Environment, Health and Safety management at all sites, the company’s responsible management of its historical legacy and responsible product management. The report was awarded the best environment report in Belgium by the Belgian Institute of Chartered Accountants.

Basic level: The baseline level to be attained in every plant;

Medium level: Compliance with EU Directives on control of major accidents (Seveso Directive or international equivalent);

Business Excellence: The ultimate goal for all operations, which included all aspects of excellent health and safety management.

Umicore continued to develop its communication on environmental matters, through the medium of a community relations website, part of its community involvement program. The company was also proud to communicate that its Environment and Safety report was elected the best in Belgium by the “Reviseurs d’Entreprises/Instituut der Bedrijfsrevisoren”. At the same time the Belgian association of financial analysts awarded Umicore the prize for best financial communication in 2002. The company was also included in the FTSE4GOOD index and received the ‘best in class’ rating from the Storebrand Social Responsibility Index.

In 2003, the Environment and Safety report became “Environment, Health and Safety report” with the tagline “Environment, health & safety and business growth go hand in hand”. Year after year, the company was enlarging its scope of reporting and now paid more attention to the employees by including health issues. That same year, Umicore was selected for membership of the new Kempen/SNS Smaller Europe Social Responsibility Index.

The company then published “The Umicore Way”, a framework of guiding principles and a statement of what was common and essential for the Group. The Umicore Way explains the vision of the Group and the values it seeks to promote. It serves as a reference point for all employees. The Umicore Way was introduced by means of an extensive roadshow carried out by Umicore’s senior management which visited seven locations in four continents.

The adoption of a Code of Conduct for all Umicore employees followed the declaration of the Umicore Way. It provided a statement of ethical business practices throughout Umicore. It was distributed throughout the group and has been translated into four languages. By 2005 the continuous improvements in performance, management systems and participation by sites led to the publication of one single annual report, including economic, environmental and social sections. The audience was enlarged: as it was recognized that the scope of people entitled to information about how Umicore did business went beyond the boundaries of the investment community and the report was therefore addressed to “Shareholders and Society”. Furthermore, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Guidelines were adopted, as a standard. This Annual Report begins to reflect Umicore’s approach to sustainable development.

The work on reporting was supported by publishing reports for the local community (which included the families of many employees of the plants) coupled to an open doors approach at the plants in Hoboken and Olen and in the corporate headquarters in Brussels each year.

By the end of 2005, the majority of earnings derived by Umicore were from areas in which the company held global leadership positions and where it could rely on its distinctive technological capabilities. At the same time, the concept of sustainable development had become firmly embedded in the strategic thinking, and was notably exemplified by its commitment to closed loop manufacturing and recycling. In that year Umicore was elected 42nd worldwide for combined financial and CSR performance by Newsweek Japan.

Diffusion and Institutionalization

We can say that over the last few years we have moved ahead on many fronts: in tackling the legacy of past activities, in ensuring that the environmental performance of our present processes are in line with ever more demanding standards, and – most importantly – by contributing to a better environment through the development of innovative products and a commitment to recycling. For the future, we will progress on this Umicore Way. (Thomas Leysen, Umicore EHS Report 2004)

The eight environmental objectives for the period to 2005 were complemented by five new objectives on the social front again to be realized over a period of 5 years. In this way, importance was given to the relationship of the company to society as well as the environment – with a focus on employees and local community. At the same time the three environmental axes were extended and disseminated on a global basis.

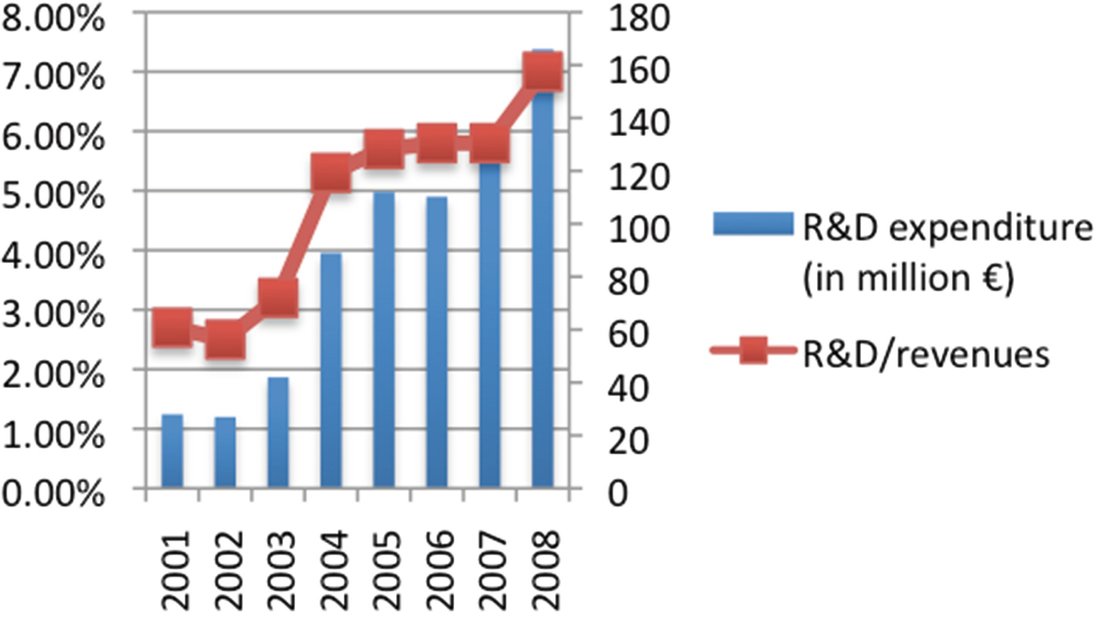

R&D expenditures 2001–2008 (Source Umicore)

During this phase Umicore continuously refined its communication, through its annual reports. For example Umicore applied the principles of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) to its reporting framework since the publication of the 2005 Report to Shareholders and Society.

Overall Umicore built on the lessons learnt in Belgium and then in wider Europe to effect organizational transformation in its other sites around the World. This followed the main themes of its overall approach employee engagement through surveys and support for innovation, fostering quality employment and health and safety of the employees and engagement with local communities around its sites, in case of the environment – cleaning up the past, continuous improvement of operations and a focus on precious metals and internationalization with this all supporting a business moving toward materials based on closed-loop systems with environmental and clean technology applications.

Discussion

The case narrative above states the main phases in the transformation of Umicore over 19 years. It follows what happened chronologically, as reported by the key informants. It identifies the overall process into five phases, the key elements and sequences of that transition and the role played by senior managers. In this way the case provides insight into the roles and beliefs of those leading the transformation process. In this discussion section we draw on theory to make some sense of the process that is described and the role of human agents in that change process.

The literature identifies the central role of change agents in transformation to sustainable development but without going in to great detail as to what the role of change agents involves (Dunphy et al. 2007; Mayon-White 2003; Beckhard 1997). Despite the emerging complexity of change agency in relation to sustainable development and its implications for business few attempts have been made to clearly define a process model and to reveal the factors that contribute to change. What is clear is that change agents are recognised as individuals or teams that initiate, lead, direct or take direct responsibility for making change happen (Caldwell 2003). A change agent can be considered as an agenda-setter, language-creator and moderator (Cramer et al. 2004). It has been argued that his/her changing personal values drive the process of organizational change (Hemingway and Maclagan 2004).

However change agents in the case of organizational transformation toward sustainable development have received less consideration as there are rather fewer close empirical studies of this process although authors have noted the importance of leaders in triggering change (Neilson et al. 2008; Spitzeck 2009; Gitsham 2008) Moreover it is also noted that those driving change are found primarily within the organization and express their ideas through the company’s various implementation strategies (Jonker and de Witte 2010). It has been suggested that the leadership necessary for organizational change that contributes to sustainable development is based on “the global exercise of ethical, values-based leadership in the pursuit of economic and societal progress and sustainable development” (Globally Responsible Leadership Initiative 2005). That view seems to be based on an understanding of the interconnectedness of the world and an acknowledgement of the need for economic, societal and environmental progress. However, this kind of statement only serves to decompose and restate the qualities of sustainable development, which emphasises linking economic, social and environmental issues in ways that provide for present and future, so that this is reframed as a leadership challenge. It does not get very far into the details of the critical leadership roles and beliefs or provide more comprehensive insight into the process, especially the sequence of events that supports successful transformation for sustainable development.

In contrast D’Amato and Roome (2009) in their meta-study of companies that have engaged in transformation towards sustainable development identify eight leadership practices that contribute to the deep change required when a company sets about changing its activities to move from unsustainable practices and contribute to sustainable development. These practices include: developing vision for the future of the company; crafting strategy and policies that links commercial and environmental practices; operationalization and translation of strategy and policy to the local, operational level; ensuring top management support and involvement; engaging with stakeholders; fostering the empowerment and development of the of key actors; high quality communication; establishing systems for performance development and accountability; and, demonstrable commitment to ethical actions. Their work also points to the supporting relationship in the companies they studied that linked a future vision for the company, with concepts that help make that vision a reality, formal strategy to provide direction and resources, business principles that underscore actions and the importance of key beliefs in holding this together. These beliefs include: a recognition of problems as opportunities; only doing what you say and saying what you do; commitment to a humanistic organizational culture that values people, recognises that everyone has the potential to contribute ideas that support change and that focuses on learning, innovation and change before it focused on control. Moreover this research emphasises that successful transitions involve people and groups that fulfil certain roles that bring about this sequence: the role of creating vision; generating concepts relevant to the change; championing those concepts through organizational networks; creating communities of practice that explore, test and translate those concepts into actions and new practices. This is supported first by communicators and then by the role of those who develop and deploy management systems.

The case of Umicore appears to corroborate the importance of these eight practices as well as providing some indication of the sequence through which the elements of the process are deployed, especially the link between vision, concepts, strategy and business principles.

The process at Umicore was as follows. Senior managers became aware of its pressing financial and environmental problems and sought a way out. The industrial plan provided an immediate a way out of the financial situation faced by the company but did not provide a longer term solution that would resolve the company’s environmental problems. It was nevertheless understood that past environmental problems had to be resolved and new problems avoided. That required a leap of imagination that translated environmental problems into economic opportunities. It involved an emerging vision for the company that arose from the link between two important concepts – closed material loops and clean technological applications. More hidden in the story of Umicore was a commitment to the practice of the concept of continuous improvement. The emerging vision shaped by these concepts was fostered by the move toward an organizational climate that emphasized innovation and learning founded on the empowerment of employees: Only then to be supported by a declaration of values.

In this way a vision for the company developed that it would define its future as providing material solutions to provide solutions to environmental problems while ensuring that the company’s operations accorded with the highest possible environmental standards. Moreover the company would progressively move toward a closed loop business.

The model to fulfil that vision was not immediately obvious – it came from testing and experimenting with these ideas in one business unit and then progressively up-scaling that experience to other parts of the company and its business. This required the development of an awareness of the new approach among employees, coupled to their empowerment and encouragement of their engagement in learning and innovation to deliver the practices that would make the vision tenable. Only once this cultural change was in place could the company press ahead with the development of a management, performance and reporting system. The management system was gradually extended and expanded into the whole of the organization but it too followed the development of the culture of learning and innovation as the management system itself was seen as an innovation.

At Umicore there was an period of iteration between the emerging vision for the company on the one side and concepts that would be central to that vision based on the promotion of a more open and innovative culture, on the other.

Once the vision was clear, and the concepts had been tested and seen to provide a viable approach for the company it was able to embark on an acquisition and divestment strategy that closed its material loop in some main business areas and got out of areas that did not conform to the new approach. At the same time acquisition of businesses provided new know-how although it created challenges of integrating those businesses into the culture and approach taken by Umicore.

Intense communication by the CEO’s coupled to the use of formal documents such as reports and community liaison was seen as critical and this too was gradually developed and pushed forward so that claims were in line with achievements and words matched actions. Significant attention was given to key communications – the logo, slogans and name of the company developed in a rhetorical way so that it signalled change that had been made and inspired more movement in that direction. A premium was placed on transparency and admitting to and addressing the problems of the past.

Above all the case illustrates the importance of the continuity of belief systems of the three CEO’s and the matching roles that supported the accomplishment of transformation. Despite their different experiences the three CEO’s all placed a premium on human relationships, communication and matched that with a commitment to learning.

Finally, the case indicate that senior managers at Umicore had a simple yet compelling understanding of the implications of sustainable development. This is not a trivial point. Senior managers understood sustainable development as a strategic challenge and opportunity some 15 years ago. And they south to work out what that would mean for change at the company. Moreover, their quest was not to claim sustainability for the company but to acknowledge clearly that Umicore was a business seeking to create value and profit but that did not pre-determine how it would create value. Given the company’s history senior managers seemed to know that the company’s longer term future would be based on a choice of how they did business, and how they chose to create value into the future. That would mean breaking with the ways of the past that had created value while at the same time destroying environmental value. The key issue was how to identify the path for transition and to develop the skills and know how that would make it successful.

The company’s senior managers set out to determine the direction for the company through the combination of vision and concepts, to encourage the commitment and alignment of employees and others to that direction but to leave the detailed operationalization to those closer to the operational realities of the company.

Conclusions

This chapter set out to examine the process of transformation undertake by Umicore a company that is widely held to be a leader in its contribution to sustainable development. The chapter describes that process using the insights of those who were close to the process that unfolded over 19 years. That process is still not complete but much has been changed.

The chapter sheds light on the sequence of this process and the factors that contributed to the way it unfolded. It shows something of the practices that support the process of change and the roles and beliefs that were held by change agents and leaders. These conform to evidence from previous companies that have undertaken similar transitions.

What is clear is that Umicore held a somewhat unusually advanced yet simple view of sustainability, a view that is rather consistent with the original understanding of sustainable development as set out in the Brundtland report. But the real value of the case is in the charting of process that then unfolded: Creating a culture of learning and innovation to provide for change. Developing a new vision for the company that was supported by the deployment of some key concepts that were relatively new to the company. That required learning about those concepts by doing. In other words transformation, to make a contribution to sustainable development at Umicore, was essentially an innovation process that deploys some concepts that were not conventional for the business and required management to subscribe to some relatively rare skills. The fact that the transformation at Umicore involved a simple yet advanced notion of the implications for the business of sustainable development, deployed some unconventional concepts and drew on some rare skills possibly explains why so few examples of successful transformations toward sustainable development are available to study.