In September 2005 Iftekhar Enayetullah and Abu Hasnat Md. Maqsood Sinha, the founders of Waste Concern, secured approval for their first project under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) program, established in the Kyoto Protocol. Under the CDM program, projects reducing greenhouse gas emissions in countries without emission targets could earn income from the sale of Certified Emission Reduction units (CERs).1 CERs could be sold to industrialized and transition countries obliged to reduce their emissions in the Kyoto Protocol. The CDM program is supervised by the CDM Executive Board under the authority of the Conference of the Parties, the governing body for the Protocol.

The approval for the second project of Waste Concern came in May 2006. The two projects encompassed a plan for a dual-purpose operation consisting of a gas recovery site and a 700-ton per day composting plant at the Matuail landfill site in Dhaka. The Matuail Landfill site was owned and governed by the Dhaka City Corporation (DCC), which was also responsible for the collection of waste from the streets of Dhaka. For their CDM projects, Waste Concern planned to use the landfill site provided by the DCC. The organization also wanted to take over the waste collection from the markets in Dhaka, with the idea to turn the collected waste into saleable compost. In addition, it planned to earn income by selling CERs.

The projects seemed a win-win scenario for all stakeholders. Firstly, the projects could earn income for Waste Concern and at the same time help the organization to achieve various environmental and social benefits, including the reduction in greenhouse gases and creation of new jobs. Secondly, they could help Dhaka City Corporation as it was struggling with collecting the growing mountains of waste generated by an increasing number of Dhaka residents. Thirdly, the emissions could be traded with industrialized and transition countries to help them achieve their emission targets and, thus, the projects could promote the CDM and help realize the Kyoto Protocol.

However, the reality faced by the two founders of Waste Concern when implementing the CDM projects differed substantially from the business plans. The carbon market plummeted and with it the prices that could be achieved through selling CERs. The Dhaka City Corporation did not allow Waste Concern to access the Matuail Landfill site. Additionally, the electricity crisis impacted the number of composting plants that they could built as no new grid connections were allowed by the government.

Yet, Enayetullah and Sinha and Waste Concern managed to deal with these challenges and turn them into opportunities: (1) They found a new site for the composting project and built their first composting facility on that site; (2) They gradually increased the capacity for the first composting plant when they were not able to build more plants; (3) They introduced technological innovations such as Refuse-Derived Fuel to gain additional sources of income for their projects; (4) They exported the compost outside of Bangladesh for higher prices than possible within the country; (5) They secured an agreement with the Asian Development Bank to sell their CERs at the lowest cut-off point predicted in the business plan. At the same time, Waste Concern focused on scaling up its waste management solutions outside of Bangladesh with the help from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It also started a new company promoting organic produce in Bangladesh. Waste Concern, founded in 1995, was growing every day.

As a result, on the cusp of the eighteenth birthday of Waste Concern, its founders were running a different organization. They were proud of their achievements, but – keeping recent challenges in mind – they were also wary of the future and the tasks lying ahead.

From a simple non-profit, Waste Concern evolved into a hybrid organization doing business with a social mission of making waste a resource. It literally was “making cash from trash” (Ashoka n.d.), dealing with the challenges that no private business in Bangladesh wanted to deal with.

In addition, by engaging in CDM projects, cooperating with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and engaging in the marketing and sale of organic products, Enayetullah and Sinha expanded their organization in Bangladesh and abroad. The evolution from a lean research, development and advisory services operation to a broader diversified venture encompassing four companies, dealing with waste management and organic agriculture as well as managing the Waste 2 Resource Fund also created new organizational challenges.

The identity of the organization was in constant flux. For one, Enayetullah and Sinha saw themselves as serial entrepreneurs, designing and developing innovative solutions to improve the waste management situation in Bangladesh. With the two founders representing both the identity of Waste Concern towards external stakeholders and most of its management capacity the question of how to structure the organization for future growth and impact became more prominent.

Bangladesh

Located between India and Burma, Bangladesh has a land area of 144,000 km2 and a population of nearly 164 million people (Central Intelligence Agency 2013).2 The country has the eight largest populations in the world and also one of the highest population densities at 1137 people per km2. It was estimated that approximately 28% of the country’s population lives in an urban area. This was expected to increase at 3.1% annually.

Observers cited extreme monsoons and cyclones as the central impediments to growth creating climatic instability. Additionally, poor transportation and communication infrastructure, insufficient energy sources and ineffective government reduce growth potential. However, last year the Economist named Bangladesh “one of the most intriguing puzzles in development” (The Economist 2012) describing the country as making social progress, especially when it comes to mortality rates of infants and mothers at birth, as well as life expectancy. Social progress, though, did not go hand in hand with economic development, with GDP per capita ranked 192nd out of 229 countries. GDP per head was around USD 2000 in 2012 and approximately 31.5% of the population lived below the poverty line. See Exhibit 26.1 for more facts about the country.

Exhibit 26.1: Bangladesh at a Glance

2005 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|

People and society | ||

Population | 144,319,628 | 163,654,860 |

Median age | 21.87 | 23.9 years |

Population growth% | 2.09% | 1.59% |

Birth rate | 30.01 births/1000 population | 22.07 births/1000 population |

Death rate | 8.4 deaths/1000 population | 5.67 deaths/1000 population |

Maternal mortality rate | 330/100,000 live birthsa | 240 deaths/100,000 live births |

Infant mortality rate | 62.6 deaths/1000 live births | 47.3 deaths/1000 live births |

Life expectancy at birth | 62.08 years | 70.36 years |

Total fertility rate | 3.13 children born/woman | 2.5 children born/woman |

Economic indicators | ||

GDP (purchasing power parity) | 299.9 billionb | 305.5 billion |

GDP growth rate | 5.2% | 6.1% |

GDP/capita | 2100 | 2000 |

Inflation | 6.7% | 8.8% |

Unemployment | 2.5% | 5% |

Population below poverty line | 45% | 31.5% |

Public debt as% of GDP | 46.1% | 32% |

Industrial production growth rate | 6.7% | 7.4% |

Current account balance | −591 million | −942 million |

Exports | 9.372 billion | 25.79 billion |

Imports | 10.03 billion | 35.06 billion |

Currency | Taka (BDT) | Taka (BDT) |

F/X rate to US$ | 64.26 | 82.17 |

Energy and environment | ||

Electricity production | 17.42 billion kWh | 35.7 billion kWh |

Crude oil production | 6825 bbl/day | 5200 bbl/day |

Natural gas – production | 9.9 billion cu m | 20.13 billion cu m |

Carbon dioxide emissions from consumption of energy | 37.65 million Mtc | 56.74 million Mt |

Dhaka and Waste Management

Population in urban areas such as the nation’s capital, Dhaka, reached 43,000 people per km2. Dhaka is home to 15.4 million people and is expected to grow to 22.9 million by 2025 (World Urbanization Prospects, the 2011 Revision 2011). The residents of Dhaka generate almost 5000 tons of waste per day (CNN 2012). This compares to over 16,000 tons of waste generated per day in urban areas of Bangladesh (United Nations Centre for Regional Development 2011). This number is projected to nearly triple by 2025–47,000 tons of waste per day (United Nations Centre for Regional Development 2011). In Dhaka, approximately 70–80% of the waste is organic and the remainder is paper, plastic, glass and other man-made materials.

The Dhaka City Corporation (DCC) is responsible for collecting all solid waste in Dhaka. Estimates from the late 1990s show that the DCC was able to collect only 51% of all waste (Hai and Ali 2005). Nearly 9% of the waste was collected by individuals known as Tokais, informal waste collectors seeking plastic, glass or paper to sell it to recycling factories for cash. See Exhibits 26.2 and 26.3 for some photos and the link to the video with more information on the waste problem in Dhaka and Bangladesh.

Exhibit 26.2: Dhaka Waste Problem

Source: Waste Concern documents, Accessed 02 June 2014

Exhibit 26.3: CNN Documentary Video on Waste in Dhaka and Bangladesh, Featuring the Founders of Waste Concern

Source: CNN (14 May 2012), Dhaka’s Uncollected Waste, http://edition.cnn.com/video/data/2.0/video/business/2012/05/14/future-cities-dhaka-waste-rubbish.cnn.html, Accessed 12 June 2013

Early Trajectory of Waste Concern

Enayetullah and Sinha met in 1993 while conducting research for their Master theses in Dhaka. These two graduate students with backgrounds in urban planning found that they had something else in common. They believed that the increasing amount of waste produced in Bangladesh was a serious problem. They both had ideas on how to mitigate it: “Both of our research findings had one common feature which was that we must do all we can to convert waste into resources, because the conventional system of collection and dumping will not solve the problem.” 3

As part of their postgraduate research, Enayetullah and Sinha set up a model of waste management whereby solid waste was collected and composted. The compost would then be used as a substitute for chemical fertilizer. They initially decided to approach governmental officials with this model, offering advice on waste management, but they were not successful: “Nobody was interested initially; they laughed and said we were graduates fresh from university, with new theories and ideas which were not practical”. One official suggested to them that they should pursue their ideas solo. That is what they decided to do: “This advice changed our life, although we were little bit frustrated but it showed us to think differently.”

First they secured a piece of land in Mairpur, Dhaka with the help of a local Lion’s Club. They used the land for experiments with different methods of composting, including the Chinese Covered Pile System (anaerobic method, where waste was placed underground in a pit) and the Indonesian Windrow Technique (aerobic method, where waste was piled in large heaps on top of a wooden structure and turned every 4–5 days). The latter method proved to be the best solution for Dhaka, as the first radiated smelly gas. Enayetullah and Sinha further adapted the Indonesian method to Dhaka’s conditions. As a result, they produced good quality compost and the Lion’s Club allowed them to continue work on the land.

Waste Concern (1995)

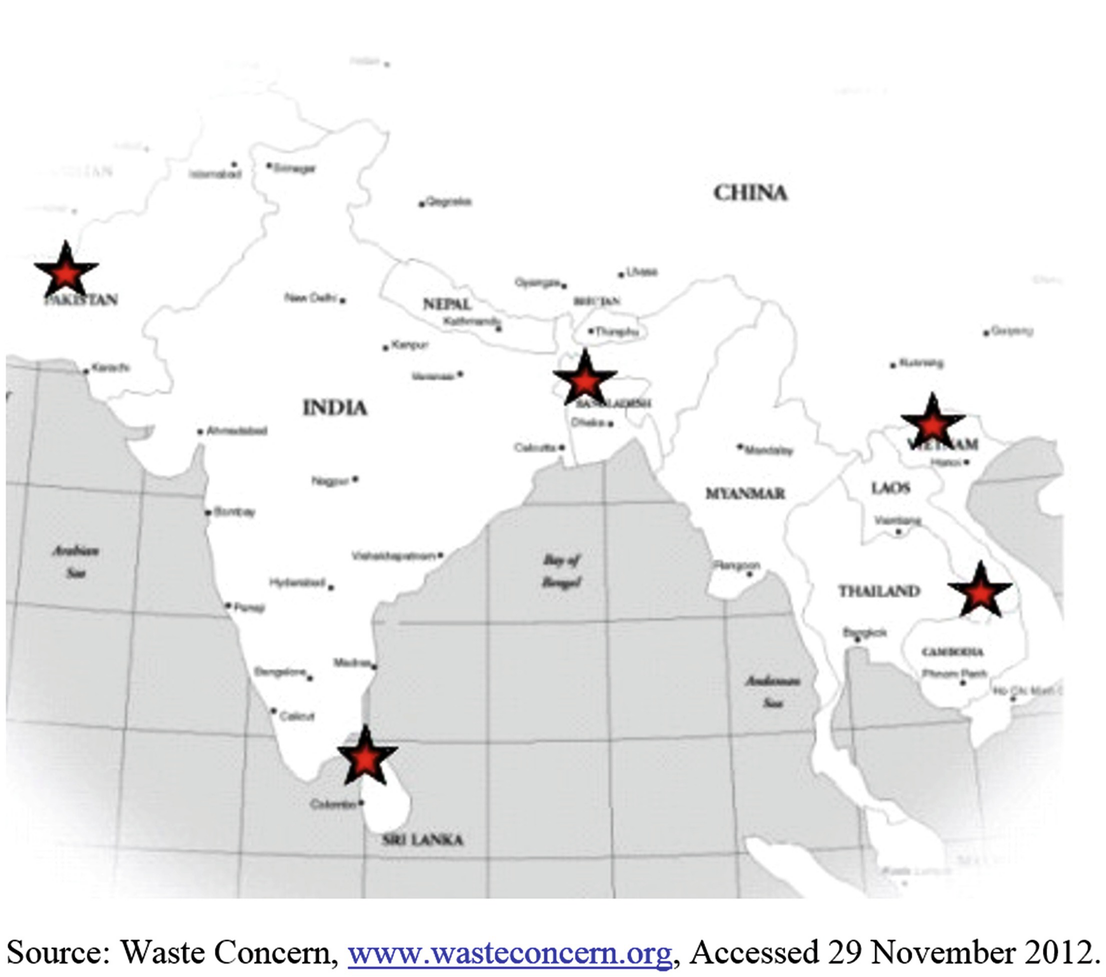

In 1995 Enayetullah and Sinha decided to register Waste Concern with the aim of promoting the idea of converting waste into a resource. The organizations proceeded to use the Lion’s Club land as a demonstration ground for its composting solution. See Exhibit 26.4 for a regional presence map and more information about Waste Concern.

Exhibit 26.4: Waste Concern at a Glance

Vision

Mission

Regional Presence

From the beginning, Waste Concern experimented with different methods of waste recycling in order to reduce time and space needed for waste composting. To replicate its solutions in other communities in Dhaka, Waste Concern teamed up with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 1998. Replications outside Dhaka were possible from 2000 – again due to UNDP support.

In 2002 Enayetullah and Sinha assumed the role of technical partner/consultant for the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the governmental Department of Public Health Engineering. Thus, they extended their work to additional cities in Bangladesh. Next, in 2000, international replication started in partnership with the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP).

Waste Concern Consultants (2000)

Waste Concern relied on external funding as the organization was structured as a non-profit: “Financing was coming either from UN agencies or the government. That was the area where we again thought that we are having impact but we are dependent too much on financing from the public sector.” Waste Concern as a non-profit was not able to generate its own income, nor get a bank loan. During meetings with potential loan providers, it was suggested that the founders need to make a change in Waste Concern’s organizational structure through introducing a for-profit arm.

As Enayetullah and Sinha were often approached by external organizations and asked to provide consulting services, they decided to open a consulting business: “People are requesting us to give advisory services to different projects. And then we look into it that this is not possible through Waste Concern. If we do it, at one point of time, there would be a question mark within the board, and with the government, like why are you doing it? This has happened with many of the organizations in Bangladesh.”

As a result Enayetullah and Sinha decided to register their first for-profit venture, Waste Concern Consultants, in 2000. Thirty percent of the profits from this venture were going directly to Waste Concern non-profit to provide funding for researching new solutions on how to convert waste into resources.

WWR Bio Fertilizer Bangladesh, Ltd and Matuail Power Ltd (2005)

In 2002, Enayetullah and Sinha as consultants were approached by the UNDP and the Ministry of Environment and Forest of Bangladesh. They were asked to identify the starting points for the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects in Bangladesh. As a result, they produced a baseline study and business plans of the first CDM projects in the country.

After completing this assignment, Enayetullah and Sinha were concerned about the lack of efforts to implement any of these business plans. This triggered the idea to implement them as a part of Waste Concern. Thus, in 2003, Waste Concern started pursuing the landfill gas recovery and composting projects envisaged in the baseline study and business plans from 2002. The majority of waste in Bangladesh was organic and the founders of Waste Concern saw a great potential in converting this waste into compost and thus, on the one hand – solving the problem of waste, on the other hand – selling compost and generating other revenue using the CDM. No other organization in Bangladesh was doing something like this.

Waste Concern started looking for investors for these ideas and decided to continue the CDM work: “Then we informed UNDP that we are going to carry this on beyond the project. They actually got really interested in that.”

Enayetullah and Sinha also engaged in the policy making activities and helped to create and develop the Designated National Authority for CDM projects in Bangladesh.

In 2005, in continuation of their work on CDM projects in Bangladesh, Waste Concern established two special purpose companies – WWR Bio Fertilizer Bangladesh, Ltd. and Matuail Power Ltd. See Exhibit 26.5 for more information about the two companies.

Exhibit 26.5: Information About the CDM Projects Invented by Waste Concern

Landfill gas extraction and utilization at the Matuail landfill site, Dhaka, Bangladesh | Composting of organic waste in Dhaka, Bangladesh | |

|---|---|---|

Project number | Project 0078 | Project 0169 |

Project design document date | 1 July 2004 | 9 December 2005 |

Registration date | 17 September 2005 | 18 May 2006 |

Project participants | World Wide recycling BV, Netherlands; Waste Concern, Bangladesh | Waste concern; World Wide Recycling B.V; WWR Bangladesh Holding BV; and Asian Development Bank, as trustee of the Asia Pacific Carbon Fund (approved November 2012) |

Brief description of the project activity | The project aims to realize a landfill gas extraction and utilization project at Matuail landfill site near the capital Dhaka in the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. The extracted gas will be used on-site for electricity generation by gas-engines. The project comprises the design and engineering of the extraction system according to modern standards, all equipment delivery (wells, piping, compressor(s), flare, gas-engines, grid connection, etc.). It is the intention of the project proponent to reshape the landfill (in order to extend the lifetime of the landfill) and introducing proper landfilling techniques such as a.o. leachate collection | The project objective is the realization of a composting plant for organic waste on a site in the capital Dhaka of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. The project comprises the design and building of composting plants for waste from Dhaka city, with a total maximum daily input capacity of 700 tons, according to proven standards. The project contributes to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions as the project activity provides an alternative to the original baseline scenario in Dhaka in which organic waste is disposed at local landfills. The anaerobic conversion of organic waste at the landfill generates methane gas (CH4) that emits into the atmosphere. By converting the organic waste from land filling towards composting, landfill gas methane emissions are for 100% being prevented |

Public-private partnership model | Project participants intended to use the landfill site of Matuail near Dhaka, operated by Dhaka City Corporation (DCC). WWR and WC intended to take over the activities at Matuail landfill and introduce proper landfilling techniques | The establishment of composting plants in Dhaka is based upon a concession contract with the Dhaka City Corporation in which the local company WWR BIO has been granted the right to collect organic waste from local street markets in Dhaka. Under the concession contract, which has duration of 15 years with a starting date of January 2006, WWR BIO can collect up to 700 tons of organic waste per day |

To establish the companies, Waste Concern first searched for suitable partners. This was one of the external requirements for implementing CDM projects: “To do the CDM project, you need a partner from a developed country and from a developing country. It is a trading. We cannot do it with Bangladesh organizations alone.” In the process of looking for a suitable business partner, the organization rejected those businesses that were clearly focused only on profit maximization, operating without social objectives. In the end, it opted for more socially minded partners – World Wide Recycling (WWR), Triodos Bank and the Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO).

Next, Waste Concern secured funding for the companies: “Why don’t we make the project bankable? We talked to several foreign banks, they said they were able to finance our projects, although it had a low rate of return for them and it was not commercial project (ed.). But it had a huge social environmental benefit (ed.).”

Later, Waste Concern registered its CDM projects with the CDM Board. It also established a clear financial structure for these new ventures. All investors became shareholders in the created companies. In the case of Waste Concern, Waste Concern Consultants became a shareholder and Waste Concern took a role of a project participant in the CDM activities: “Project participant is that Waste Concern will ensure in the project that the low income people are benefiting (ed.).” Profits generated by the companies were distributed proportionally to all shareholders. Waste Concern Consultants’ profit share was used to finance non-profit activities of Waste Concern – that is was used for research and development.

Waste Concern CDM Projects

CDM Plans

Waste Concern created its first special purpose company, Matuail Power Ltd., to extract landfill gas and generate grid connected electricity at the Matuail landfill site in Dhaka. The Matuail landfill site was owned and governed by the DCC.

Under the second special purpose company, WWR Bio Fertilizer Bangladesh, the organization wanted to construct three composting plants in Dhaka. Initially, it aimed at building the plants on the Matuail landfill site governed by the DCC. It also wanted to secure an agreement with the DCC to collect waste from Dhaka: “We collect the waste free of cost for the city, so that we are helping the city. That was one of the mandates.”

CDM Challenges

As mentioned above, both special purpose companies relied on the access to the Matuail Landfill of DCC. However, access to the site was eventually not provided by the DCC. In addition, Waste Concern experienced some problems due to the volatility of the carbon market. When it started its CDM projects, the price of CO2 was high, at some point even above 30 euros per tonne. Then the price plummeted down, at some point even to near zero. Although Waste Concern planned for decreases in prices, nobody envisaged that the carbon market could be close to crashing down. Waste Concern planned for 4.5 euros as the lowest price for 1 tonne of CO2.

Furthermore, Waste Concern was not able to open additional plants as planned, as due to the energy crisis in Bangladesh, the government did not permit new grid connections.

CDM Strategic Reactions

Strategy 1: New site for the second project

First compost plant created by WWR Bio Fertilizer Bangladesh opened in November 2008 in Bulta. Arranging for financing, land and governmental permits took considerable time and delayed the opening of this plant.

Strategy 2: Increased capacity for the existing compost plant

Waste Concern decided to gradually increase the capacity of the existing plant when the electricity crisis in Bangladesh made it difficult to open new plants.

Strategy 3: Refuse-Derived Fuel

The founders of Waste Concern developed a new technology for utilizing waste rejects from the compost plant and turning them into fuel. This Refuse-Derived Fuel can be sold and increase the cash flow for the CDM projects.

Strategy 4: Exports of compost outside of Bangladesh

Waste Concern also looked for opportunities to sell its compost abroad to Malaysia and the Middle East Countries. The organization was successful and obtained higher margins than for selling compost within Bangladesh.

Strategy 5: Agreement with the Asian Development Bank

Moreover, Waste Concern signed the agreement with the Asian Development Bank to sell its carbon credits at the lowest price predicted in the original business plan (4.5 euro). See Exhibit 26.6 for more information about the CDM challenges encountered by Waste Concern and how the organization responded to them.

Exhibit 26.6: Challenges and Strategies for Waste Concern CDM Projects

Project name | Project number | Challenges | Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

Landfill gas extraction and utilization at the Matuail landfill site, Dhaka, Bangladesh | Project 0078 | 1. Dhaka Municipality does not allow the access to the Matuail landfill site | 1. Waste concern could not implement this CDM project. The organization focused on the second CDM project as well as on other activities (e.g., waste to resource project and waste concern Baraka Agro Products company) |

Composting of organic waste in Dhaka, Bangladesh | Project 0169 | 1. Problems with the access to the Matuail landfill site | 1. Changed the project site to Bulta |

2. Only one composting plant built due to power crisis in Bangladesh – no new power connections were allowed | 2. Expanded the capacity of the existing plant | ||

3. Lower than expected prices of CER | 3a. Diversified income sources by innovating with RDF and exporting compost outside of Bangladesh | ||

3b. Secured an agreement with the Asian Development Bank to buy out all CERs for set prices (higher than at the market) |

New Ventures of Waste Concern

Recycling Training Centre (2005)

At the same time as developing CDM companies, Waste Concern engaged in yet another project. In 2005 the organization started working on the first dedicated recycling training centre in Dhaka supported by the UNDP Sustainable Environment Management Program. The aim was to increase Waste Concern’s impact through promotion of recycling among governmental officials, Waste Concern staff, and prospective entrepreneurs: “We thought that we needed to bring more people into this, so we established a training centre in Dhaka. (…) We tried to create an entity so that at one point it raises awareness and creates manpower (ed.).”

Waste Concern Baraka Agro Products (2006)

Enayetullah and Sinha also innovated around organic produce and created another new company – Waste Concern Baraka Agro Products. The company’s aim was to promote organic food and sustainable agriculture and create green jobs in Bangladesh. On this venture, they partnered with Ahmed Amin Group.

Initially, Waste Concern Baraka Agro Products was to produce organic food. With time, the company added solar power irrigation and organic cotton to its products. The idea to grow organic cotton was driven by the governmental programme promoting cotton cultivation in Bangladesh. Enayetullah and Sinha seized this external opportunity.

Additionally, through their Schwab Foundation networks, they managed to convince a British based organic clothing company, People Tree, to pre-order their first organic cotton yield.

Waste Concern Baraka Agro Products succeeded in growing first organic cotton in Bangladesh. However, shortly afterwards, the company experienced some problems with cotton seeds, which had to be shipped from India. Thus, it rethought its organic strategy and decided to focus efforts on growing other organic produce as well as securing organic certification: “The Agro Product project is on, and we are working for certification. It takes around three to four years to get full certification for organic crops, and we are in the process of doing so.”

Waste 2 Resource (2009)

Then, in 2009, Enayetullah and Sinha were approached by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to extend waste recycling training to other countries in Asia and Africa. They decided to start providing training for interested organizations from abroad. They also opened a new training centre in Sri Lanka and developed manuals for composting plants to allow easy replication. Additionally, they convinced the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to create a special fund under their management to support pro-poor and sustainable solid waste management projects that reduce greenhouse gases in developing countries.

Going Forward

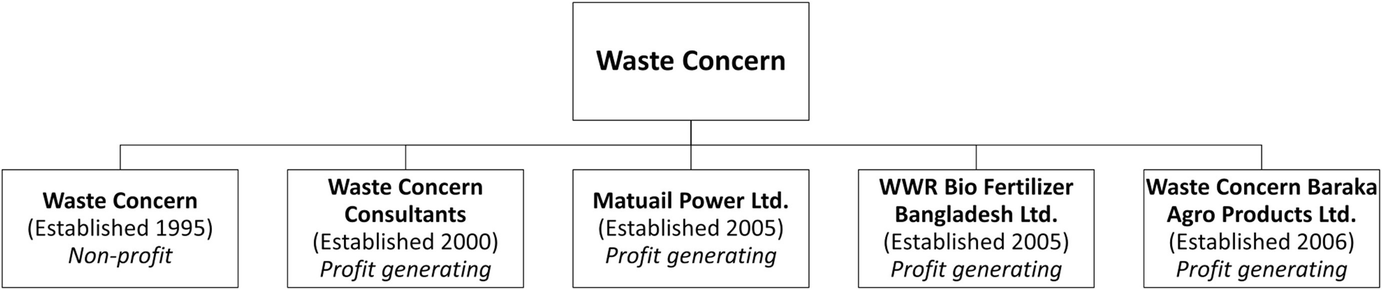

When looking back at what had been achieved in the 18th years Enayetullah and Sinha could point to an ever growing list of accomplishments of Waste Concern. The organization and its creators engaged in waste management activities in Bangladesh and abroad. They also started a number of innovative companies, including those implementing CDM projects which performed well despite the CDM market crisis. See Exhibit 26.7 for Waste Concern’s organogram.

Exhibit 26.7: Waste Concern’s Organogram

Enayetullah and Sinha saw themselves as serial entrepreneurs, developing new ideas, patenting them, passing to others, and moving on to the next problem: “Our idea is to develop technology. Patent it. Give it to others. Create more companies to do it. Not by ourselves (ed.) because then you create enemies!”. When they were evaluating new ventures they followed clear principles: “One of the criteria is market failure. We always looked at whether someone has done it. If there is a private sector operating there, if there are legal instrument in place, then there is no market failure. If there is a market failure there, then we step in. This sector there was a market failure with the solid waste. We stepped in. (…).”

They also highly valued the importance of flexibility, and flexibility was possible with creation of spin-offs and letting go off their inventions: “For social entrepreneurs, or any entrepreneurs, what I believe is that you cannot make a business plan too rigid. For social enterprise, if you make a business plan that is going to be for five years, it is very difficult. It has to be very flexible, and you have to always adapt. It has to be a living document kind of thing. It cannot be a fixed master plan. If you do this, then you are in trouble. If you are opening a clear for-profit business, such as a garment factory or a software company (ed.) you can do a business plan and stick to it (ed.). But in social enterprises, operating in difficult contexts (ed.) making a pure and rigid business plan is difficult because there are many unpredictable situations.”.

This also created competition for Waste Concern: “There are now 40 companies registered, private sector and not-for-profit. Now even Dhaka city has given a contract to develop waste energy to an Italian company, just last year. People will say: “are you worried”? We say: “No, we are not worried, we are happy. We are happy that the Italians are coming with new technology, new ideas. That’s what we wanted.”

This attitude enabled Enayetullah and Sinha to start a number of innovative businesses. But at the same time, Waste Concern was increasingly facing human resource constraints that made it difficult to develop new ideas and projects. The biggest challenge was to find qualified and socially motivated professionals: “Now what we see is that the professionals who are coming to us (ed.) they are not focused. Their goal is to become rich in the shortest possible time. They apply for your company. They want a salary of 100,000 Taka, with only two years’ experience.” Another problem was connected to the lack of leadership skills among young job applicants, the problem that is probably too difficult to address for a single organization and Waste Concern has not tackled it yet: “I think for a developing country this is going to be a huge challenge because there is a leadership vacuum not only in Bangladesh but in the entire developing world. We have seen this thing in Sri Lanka. We have seen this in Nepal, in India, Pakistan, wherever you go. It’s a huge amount of population, which is too young and without role models. It’s going to be serious problem.”

Over the years, Enayetullah and Sinha became experts on waste management, not only in the eyes of the officials from the government of Bangladesh, but also among the international development organizations. They received the most prestigious awards and joined the most respected networks. See Exhibit 26.8 for more information on their network exposure and awards. At the same time, none of these achievements were accomplished easily. Enayetullah and Sinha knew too well that the path to success was not a paved road but a bumpy up-hill struggle.

Exhibit 26.8: Waste Concern’s Exposure to Networks and Awards Received

Clean Dhaka Ward Contest Award 2008 and 2009

The 6th Annual Fast 50 Award 2007

Environment Award 2007

Global Tech Museum Award 2003

UNDP The 2002 ‘Race against Poverty’ Award

Schwab Outstanding Social Entrepreneurs 2003

The Fast 50 Social Entrepreneurs 2001

Ashoka Fellowship for the year 2000

Source: Waste Concern, www.wasteconcern.org, Accessed 26 June 2013