Prologue

The data for this case study was collected in 2005. Today, 10 years later in 2015, some of the content of the systems (for example the KPIs) and the persons (for example Eric Drapé) have changed. But the tools and the challenges to integrating sustainability in Novo Nordisk remain. Instead of re-writing the case from 2005, we decided to produce an epilogue that provides the reader with an update on some of the important areas that have influenced the way that Novo Nordisk works. We hope that the epilogue anno 2015 will further stimulate discussions in the class room – and beyond – about integration of sustainability into the organization and how such integration is never a “quick fix” that is done once-and-for-all, but an ongoing and dynamic process that needs careful managerial attention and development over time.

Introduction

We all have a vision of how we’d like the world to be. For a company like Novo Nordisk committed to sustainable development, that vision is one of trust, openness, shared values and partnerships. We translate that as the Triple Bottom Line – social and environmental responsibility and economic viability. In an age where companies are scrutinised and transparency is the only way to gain trust, social responsibility is vital to maintain a business advantage. CEO Lars Rebien Sørensen, Novo Nordisk.1

Novo Nordisk is an excellent example of an organisation that attempts to consider sustainability as an integrated part of its strategy and in all of its business decisions. To meet this goal, the company has adopted a management philosophy which they call the ‘Novo Nordisk Way of Management’ to ensure all actions taken by employees meet corporate objectives. Within this management tool are three pillars that are used as control mechanisms to integrate sustainability into Novo Nordisk’s business practices: facilitators, sustainability report, and the balanced scorecard. However, it is not certain to what extent each of these pillars is effective in influencing behaviour at the operational level.

The days when Aristotle Onassis could tuck his whalers out of sight behind convenient icebergs are almost gone. New technologies and open borders render most forms of economic, environmental, and social abuse increasingly visible. Indeed, far from being drowned in a floodtide of useless information, many of the world’s citizens – thanks in large part to the public interest groups a number of them support – are becoming increasingly adept at keeping track of the activities of corporations and governments.2

Under pressure, big multinationals ask their critics to judge them by CSR criteria, and then, as the critics charge, mostly fail to follow through. Their efforts may be enough to convince the public that what they see is pretty, and in many cases this may be all they ever intended to achieve. But by and large CSR is at best a gloss on capitalism, not the deep systematic reform that its champions deem desirable.5

This case raises the question of how managers can adopt appropriate management control systems to communicate to employees and other stakeholders what behaviour is desired, and to ensure that their corporate sustainability claims are implemented at the operational level. That is, how can organisations demonstrate that their sustainability declarations are not just “good looks”. Specifically, this case unfolds Novo Nordisk’s long-term commitment to sustainable business practices and the company’s validations of these practices by focusing on how issues of sustainability have been integrated and cascaded throughout the entire organisation via the company’s ‘Way of Management’. The Novo Nordisk business unit – Diabetes Finished Products – is used an example.

Introduction to Novo Nordisk A/S

Novo Nordisk A/S was founded by August Krogh in the 1922, a Danish Nobel laureate in physiology. He was inspired by two Canadian researchers, Frederick Banting and Charles Best, who had begun extracting insulin from the pancreas of cows in the previous year. August Krogh’s wife, Marie, had type 2 diabetes; therefore, he established Nordisk Insulinlaboratorium to produce insulin for the treatment of diabetes. In 1925 two former employees, Harald and Thorvald Pedersen, established a competing insulin company, Novo Terapeutisk Laboratorium. In 1989, the two companies merged and became Novo Nordisk A/S.

By 2005, Novo Nordisk was a world leader in diabetes care; the company also held a leading position in hemostasis management, growth hormone therapy and hormone replacement therapy. Novo Nordisk previously was involved in the production of enzymes. However, a demerger in 2000 saw the establishment of Novozymes, which took over the enzymes production, leaving Novo Nordisk to focus entirely on healthcare. Novo Nordisk headquarters is located in Denmark, on the outskirts of Copenhagen, and employed in 2005 approximately 20,000 employees in 78 countries. Novo Nordisk marketed its products in 179 countries.

Appendix 1 provides Novo Nordisk’s organisational structure anno 2005. From 2002 Corporate Stakeholder Relations became part of the executive management team along with R&D, Quality, Regulatory & Business Development, Finance and Operations.

Novo Nordisk is a company based on research. Research and development expenditures equalled 43.2% of the total wage costs in 2004 and have been in the range of 15.0–16.6% of total turnover over the period 2000–2004. During this same period, Novo Nordisk had between 526 and 778 active patent families, with between 85 and 145 new patent families per year.6

Financially, Novo Nordisk has performed well, with strong growth in turnover combined with continued high profitability; the market value of the Novo Nordisk has followed the booming American pharmaceutical sector and it outperformed the European pharmaceutical index. In 2004, Novo Nordisk reported an operating profit of 6980 million Danish kroner (DKK), turnover of DKK 29,031 million and a diluted earnings per share of DKK 14.83. Additionally, Novo Nordisk reported a return on invested capital of 21% in 2004. Over the period May 1, 2004 to April 30, 2005 Novo Nordisk had a negative share return of 1.55%; however, over the last 5 years (May 1, 2000 to April 30, 2005) Novo Nordisk’s share return equalled 44.17%.7 Appendix 2 provides key financial data for the last 5 years, and return data for Novo Nordisk, the Danish market, and other large European pharmaceutical companies over the same period.

The share ownership of Novo Nordisk is developed to ensure that the organisation has a high degree of freedom, as it is not open for takeovers, for example, from larger pharmaceutical companies. Specifically, total share capital is divided into A-shares and B-shares (each B-share carries 1/10 of the votes of an A-share). The A-shares are non-listed and held by Novo A/S (which is a private limited Danish company that is 100% owned by the Novo Nordisk Foundation which was established with the merger in 1989). The B-shares are publicly traded on the Copenhagen, London and New York stock exchanges. As reported in the 2004 Annual Report, Novo A/S controls 26.1% of the B-shares, giving it 70.6% of the total number of votes. Large block-holdings of the remaining B-shares included in 2005 large institutional investors like the Danish ATP Pension Fund (4.3%), The Capital Group Companies (10%), and Fidelity Investments (4.4%). Additionally, the company itself held 6.4% of the shares. ‘Other’ investors held the remaining 48.8%, which included employees.8 Novo Nordisk’s board of directors consisted of ten members: seven elected by the shareholders and three by the employees.9 Novo Nordisk’s six executive directors as well as the directors of the Novo Nordisk Foundation were not represented in the Novo Nordisk board, which was in accordance with the general guidelines of corporate governance at the Copenhagen, London and New York stock exchanges. It was increasingly important issue to demonstrate that Novo Nordisk was doing business according to these guidelines. However, in 2000, the former CEO, Mads Øvlisen, assumed the role as chairman of the Board of Novo Nordisk..

Sustainability as Part of Novo Nordisk’s Business Strategy

Public authorities and NGOs have sharpened their tone, and we must take them seriously”, stated President and CEO of Novo Nordisk, Lars Rebien Sørensen. “It is important to be open and honest about our stand and our actions. Trust has to be earned10

Executive management at Novo Nordisk had made corporate values and sustainability an integrated part of the company’s corporate brand. Mads Øvlisen, Novo Nordisk’s chairman until 2006, often expressed strong views in the business press, and on a number of occasions on the front pages, on issues of sustainability. Many Danish business managers considered him the embodiment of corporate sustainability.11 He has participated in a number of government and business initiatives in this area, as well as contributing to the foundation of the European Academy of Business in Society and he is Senior Advisor to the Un Global Compact. He is also an adjunct professor of corporate social responsibility at Copenhagen Business School.

Whom do corporations serve? Not so many years ago, we would have said ‘shareholders’, without hesitation. But increasingly business enterprises are recognising commitments to serve other stakeholders – such as customers, employees, societies at large – in addition to shareholders. In order to serve the long term interest of stakeholders, companies must regards it as core part of their business to assume a wider responsibility and consider broadly the wide range of factors which may impact its ability to generate returns over long periods of time12

The conspicuous commitment to sustainability was reinforced in the 2004 annual report, which was the company’s first integrated triple bottom line report combining economic, environmental and social results. In the opening, the commitment was stated clearly collectively by Lars Rebien Sørensen and Mads Øvlisen on page 1 of the 2004 Annual Report:

Novo Nordisk takes a multi-pronged approach to providing better access to health through capacity building, a preferential pricing policy for the poorest nations and funding through the World Diabetes Foundation, which is now reaching out to many millions of people with diabetes. In terms of sustainability, Novo Nordisk demonstrates its determination to play a leading role by setting a target for an absolute reduction of CO2 emissions over the next decade. When people can overcome the challenges of diabetes, we must as a company tackle the global challenges of social and sustainable stewardship.

Monitoring issues and spotting trends that may affect future business

Engaging with stakeholders to reconcile dilemmas and find common ground for more sustainable solutions

Building relationships with key stakeholders in the global, international and local communities of which Novo Nordisk is a part

Driving and embedding long-term thinking and the Triple Bottom Line mindset throughout the company

Accounting for the company’s performance and conveying Novo Nordisk’s positions, objectives and goals to audiences with an interest in the company

Translating and integrating the Triple Bottom Line approach into all business processes to obtain sustainable competitive advantages in the marketplace

History of Sustainability

The focus on sustainability was not new for Novo Nordisk. In the late 1960s Novo Nordisk was confronted with severe stakeholder criticisms for the first time, and a close interaction with a broad variety of stakeholders have been part of the company’s strategy since then. Novo Nordisk’s first encounter with stakeholder criticism was surrounding new production methods that introduced genetically engineered micro-organisms, resulting in the development of a new product line of enzymes. These enzymes were important ingredients in many products (e.g., detergent). Environmentally oriented NGOs, as well as scientific articles, first raised awareness that the use of detergents with enzymes could lead to those in contact with the product developing allergies, and that the dust from the production process could have implications for employees’ health. Novo Nordisk’s sales fell dramatically, and the company reacted with a strong and fast response by developing dust-free enzymes presenting no risk for the consumers.14 Sales rose again and enzyme production became an important part of Novo Nordisk’s production in Denmark, USA and Japan.

In 2001, Novo Nordisk was once again confronted with criticism from NGOs. The pharmaceutical industry association in South Africa,, including Novo Nordisk, raised the issue of protecting intellectual property rights with the South African government. This led to major public criticism of the consortium members, who were accused of giving priority to profits at the expense of the health of less advantaged people. Again, Novo Nordisk reacted fast. By engaging in dialogue with the NGOs, the company defined a new policy to strengthen the company’s presence and development of medicines to combat diabetes in developing countries. A new pricing policy and the establishment of the World Diabetes Foundation in late 2001 can be seen as a strategic result of Novo Nordisk’s response to the criticism.

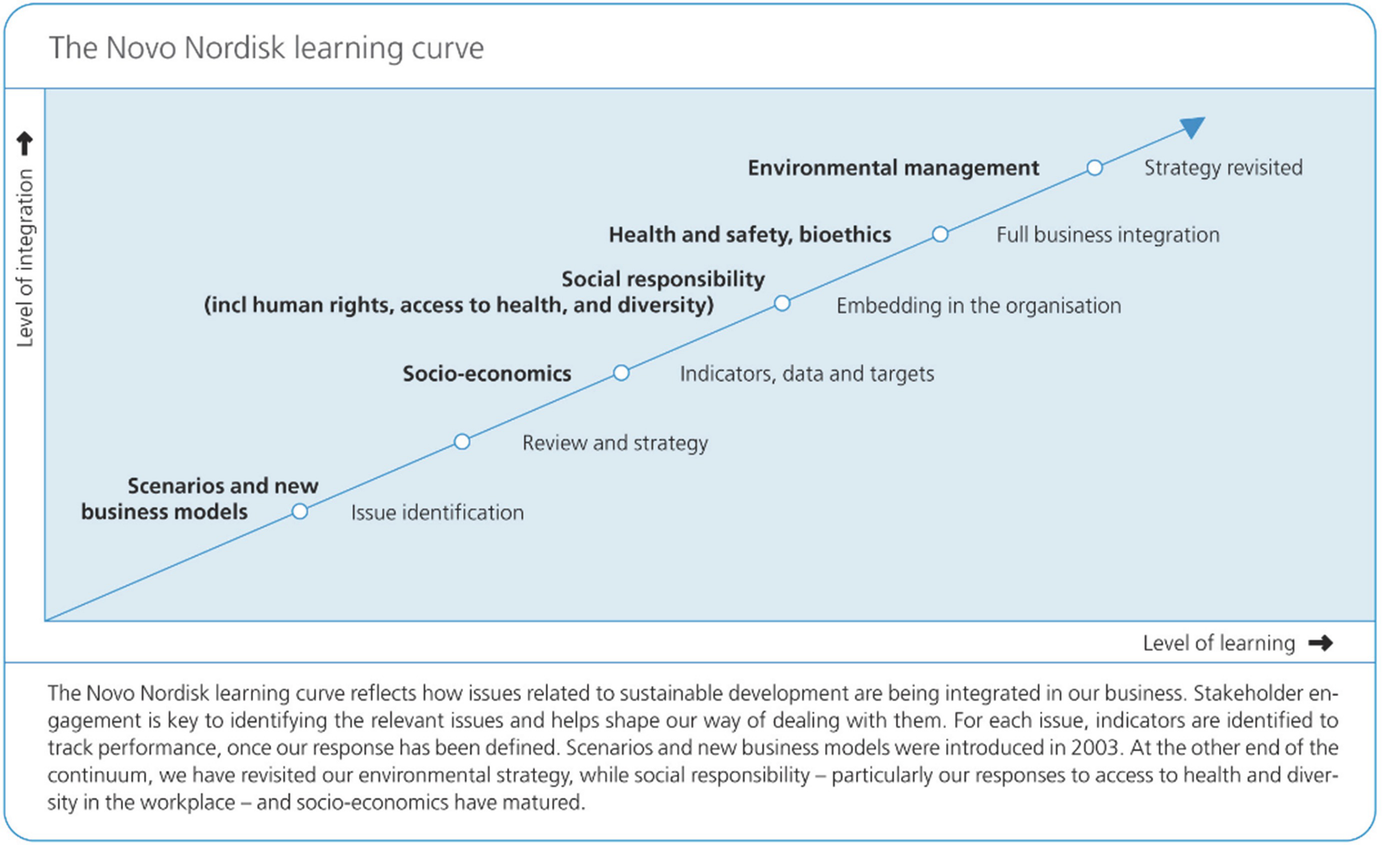

Novo Nordisk learning curve

The learning curve shows that Novo Nordisk perceived sustainability as a continuous learning process, in which the company needed to be able to take in new issues and integrate these concurrently in the business strategy towards “full business integration”.

How Did Novo Nordisk Meet Its Objectives of Being Sustainable?

The Novo Nordisk Way of Management serves as the solid footing from which innovative ideas can take off. Its immediate strengths lie in its consistency, coherence and systematic follow-up methods. It is the way we do things.16

The Novo Nordisk way of management

New initiatives and management programmes were introduced regularly, but they had no effect across borders. They were encapsulated and never seemed to make much difference outside corporate headquarters. It annoyed me, and when the Novo Nordisk Way of Management was designed as a new and overall guideline, I decided to do something about it.17

The Novo Nordisk Way of Management is a comprehensive and easy-to-use guide which should allow you to use your insight and judgment in complying also with the “local” management and quality system derived from this corporate basis for use in functions an departments throughout Novo Nordisk.”18

The Novo Nordisk Way of Management extended beyond products and manufacturing operations to include all activities, and as such it was a broad frame that described the rationale that should set the tone and the standards amongst managers and employees in the entire organization. Additionally, Novo Nordisk also developed a vision, values, commitments, and fundamentals in order to inspire and guide its employees to achieve superior performance. These are included in Appendix 3.

To ensure that the entire organisation understood and adhered to the Novo Nordisk Way of Management, the company has developed a methodology consisting of three elements: facilitators, sustainability reporting and balanced scorecard. Each of these elements is discussed below.

Facilitators

- 1.

Through on-site auditing/faciliting of departments, factories, affiliates, assess whether or not the company-wide minimum standard requirements or “ground rules” as specified in the Novo Nordisk Way of Management are met.

- 2.

Through on-site advice and help, assist the unit in question in correcting identified non-compliance with these requirements.

- 3.

Through on-site identification of “best practices” applied, facilitate communication and sharing of these across the organization.

Obtain objective evidence through a fact-finding process

Provide objective, validated assessments and conclusion

Include recommendations for improvements where appropriate

Agree on action plans with unit or process managers

Follow up on the implementation of the action plan

Fulfil their responsibilities in a manner demonstrating integrity, objectivity, and professional behaviour

The facilitation process consisted of three stages. First is the pre-facilitation, in which the scope of the facilitation was identified and material to support the process was developed. Second was the facilitation itself, in which facilitators meet with the individual unit or project members, and an agreement was made on how to improve. Finally, a post-facilitation process was conducted, in which the facilitator was responsible for following up and reporting to executive management on the achievements with respect to the action points agreed upon in stage two. Appendix 4 provides excerpts from a facilitation at the Diabetes Pharmaceutical Site Hillerød.

Sustainability Reporting

Sustainability reporting was used to ensure that sustainability thinking became part of everyday business practices at Novo Nordisk. In 1989 Novo Nordisk produced its first environmental management review as part of its proactive stakeholder strategy – long before environmental reporting became compulsory for companies like Novo Nordisk. In 1994 Novo Nordisk produced its first environmental report including resource consumption, emissions and use of experimental animals. Later, in 1998, a social report was issued, and since 1999 Novo Nordisk has published annual reports on sustainability integrating environmental, social and economic concerns.21 For the first time in 2004, Novo Nordisk integrated this information with its financial results and reported a combined social, environmental and economic report – The Annual Report 2004. These reports addressed issues recommended by United Nation’s Global Compact, the Global Reporting Initiative’s 2002 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, and followed the approach laid out in the AA1000 Framework; the reports delivered a comprehensive documentation of Novo Nordisk’s ambitions, goals, initiatives, results and new targets for environmental and social responsibility.

Novo Nordisk was renowned nationally and internationally for its dedication to corporate sustainability and for pioneering new agendas and concurrent development of stakeholder relations. Recent recognition included being ranked by Corporate Knights Inc. in February 2005 amongst the top 100 sustainable companies in the world, and being ranked second in the world by SustainAbility and the United Nations Environment Programme in November 2004 for its ability to identify and manage social and environmental issues as accounted for in its sustainability report. Additionally, their Sustainability Report 2003 won the 1st prize (for the sixth time!) of the European Sustainability Awards (sponsored by the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants), and in Denmark, Novo Nordisk had won six prizes for the best annual social report awarded by the Association of Danish Accountants and the Danish business newspaper Børsen.22 In the annual image analysis reported in Børsen, Novo Nordisk had in 1992, 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2005 ranked either one or two, with a high score on the corporate social responsibility element. In 2004 Novo Nordisk was second to A.P. Møller.23

- 1.

Living our values

- 2.

Access to health

- 3.

Our employees

- 4.

Our use of animals

- 5.

Eco-efficiency and compliance

- 6.

Economic contribution

‘Living our values’ aimed to measure whether business actions are consistent with corporate values. Three performance metrics were used to gauge how well the company performs in this area; two of which were taken from an annual employee survey (eVoice) and one was directly related to the use of facilitators (discussed above).

‘Access to health’ was included as a means to ensure that the company as a pharmaceutical company was involved in promoting improvements in global health standards. Two measures were used to gauge Novo Nordisk’s presence in less developed countries.

‘Our employees’ was included to ensure Novo Nordisk maintains high standards in relation to its workforce. Four performance measures were used to gauge Novo Nordisk’s treatment of their employees; two of these measures were taken from the eVocie employee survey.

‘Our use of animals’ was included to ensure Novo Nordisk, as a pharmaceutical company was in good standing with a key stakeholder group – animal welfare groups (in particular, the Danish Animal Welfare Society). Two metrics were used to ensure the ethical treatment of all animals used in research.

‘Eco-efficiency and compliance’ was included to measure Novo Nordisk’s impact on the environment. Four performance measures were included to measure the organisation’s use of water and energy, their compliance with regulations and the implementation of ISO 140001.24

‘Economic contribution’ was more than the traditional area of financial performance – it also covered the company’s socio-economic impacts. Five metrics were used, including traditional measures such as operating profit margin and return on invested capital, but also one metric that measured how much the company contributes to the national economic capacity (total taxes as a percentage of turnover).

The Triple Bottom Line was used as a firm wide tool to ensure Novo Nordisk took actions that were consistent with operating as a sustainable company. All metrics used in the Triple Bottom Line reported aggregate performance across all business units to present the full picture. Novo Nordisk did not report Triple Bottom Line performance at a disaggregated level (i.e., for each business unit), but did provide specific and detailed data for eight major production sites.

Transparent reporting is a vital instrument for us in accounting for our performance on the Triple Bottom Line. This is where we can account for our approach to doing business in a single document and cohesively present performance, progress, positions and strategic initiatives as well as the dilemmas and key issues we face as a pharmaceutical company. Most importantly, what we present in the report is the result of our interactions and engagements with stakeholders, said Susanne Stormer,25 then manager in Corporate Stakeholder Relations and responsible for Novo Nordisk’s sustainability reporting.

Balanced Scorecard

The Balanced Scorecard is the management tool for embedding and cascading the Triple Bottom Line approach throughout the organisation. The Scorecard is a vital element of the corporate governance set-up in Novo Nordisk and thus a very powerful tool to ensure integration of the sustainability approach into all business processes.26

Novo Nordisk had been using balanced scorecards since 1996; it was introduced primarily as a financial management tool. The administration of the scorecards rested with the Finance, Legal and IT department, which had a mandate to use the best management methods, of which balanced scorecards are viewed as an effective tool. The involvement of finance personnel with respect to balanced scorecards was to facilitate workshops (that is supporting management teams), assist in setting of targets, reviewing balanced scorecards, and changes to/improvements in financial management (i.e., integrating the balanced scorecard with processes).

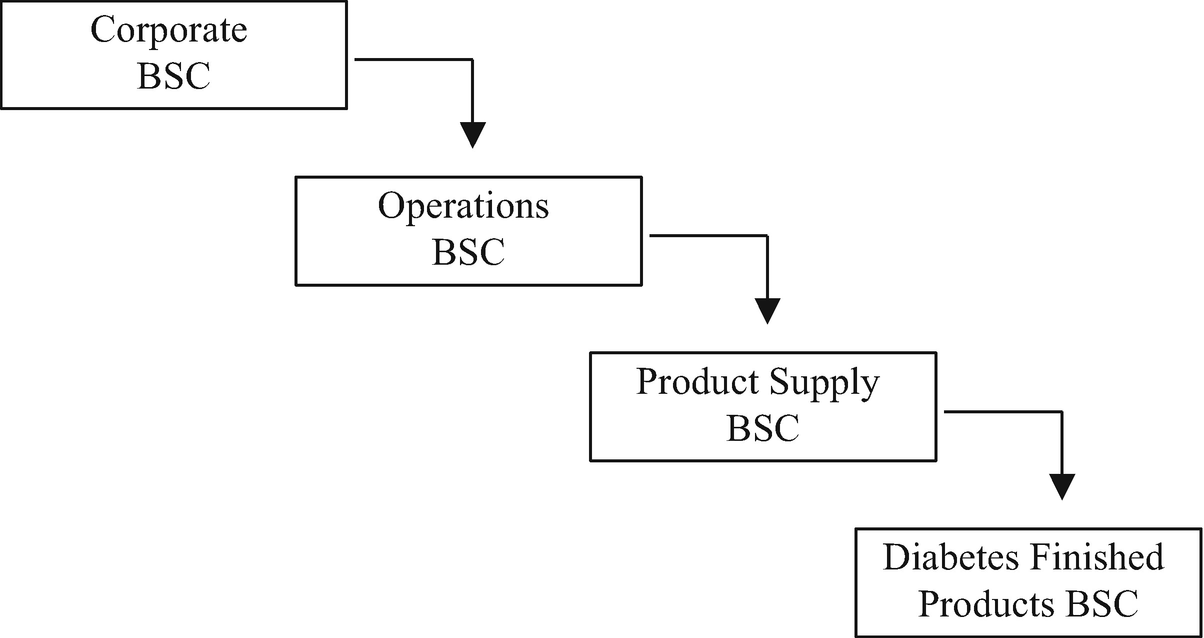

Novo Nordisk cascaded its balanced scorecard down to the business unit level, from which it translated into individual employees’ personal targets, which were set and reviewed on a biannual basis. Specifically, a balanced scorecard was prepared for the organisation as a whole; this scorecard was then cascaded down to the executive VP level (there were five executive VPs, each with their own scorecard). From this level, each of the 20 Senior VPs also had a balanced scorecard (i.e., the business unit level). From this level there was no formal mandate that the scorecards were further cascaded; however, in some business units, scorecards could be prepared for each individual sub-unit (e.g., a particular factory). In general, the sub-unit typically was evaluated on a collection of KPIs, rather than having objectives in each of the four traditional sections of a balanced scorecard.

- 1.

Increase internationalisation

- 2.

Support diversity

- 3.

Ensure talent development

- 4.

Ensure performance management

- 5.

Ensure superior company reputation

- 6.

Ensure environmental, social, and ethical performance

- 7.

Improve our collaboration with key stakeholders in diabetes care worldwide

The Use of the Balanced Scorecard at Diabetes Finished Products

One of the key business units at Novo Nordisk was Diabetes Finished Products (DFP). This group was responsible for the production and distribution of all products related to the treatment of Diabetes. In 2004, the group produced 807 million units of its four key products (Penfill® 3 ml filling, Prefilled 3 ml total, Penfill® 3 ml blister, and Insulin vials).27 There were approximately 3100 employees, spread across eight sites and DFP headquarters. Appendix 6 provides the organisational chart for DFP. Specifically, there were five production sites (three in Denmark, one in the United States, one in France); moreover, Novo Nordisk was expanding with another production facility in Brazil. Additionally, there was a logistics unit, and a manufacturing development unit that worked to take new products to mass production. Eric Drapé was the Senior Vice President of Diabetes Finished Products. Eric was a pharmacist by training, and had been with Novo Nordisk since 1990. He had been in his role since January 2004; his previous position was as a site manager (VP) at the French production facility.

Cascading of the balanced scorecard

To illustrate how specific critical success factors (CSF) were cascaded through the organisation, Appendices 7, 8 and 9 describe the KPIs, the KPI definition and the 2005 target for three CSFs for Operations, Product Supply and Diabetes Finished Products. The three CSFs illustrated were those that were most closely aligned with the social and environmental issues in Novo Nordisk’s Triple Bottom Line.

The first CSF (Appendix 7) is to ensure environmental, social and ethical performance. With respect to DFP only one KPI was included, EPI performance, which was intended to measure the relation between total yield of product and consumption of water and energy. Further up the organisation, the emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) was also measured. Noticeably missing from the corporate balanced scorecards28 were any KPIs which measured social and ethical performance – most likely a reflection of the general difficulty of defining meaningful and quantifiable social indicators at a corporate level.

The second CSF (Appendix 8) was a focus on supporting diversity and social responsibility. Throughout the organisation three KPIs were used. The first was intended to ensure that each level of the organisation supported diversity and ensured equal opportunities to its employees. The second was the number of employees that had evaluated progress according to the OA. Finally, was a metric which focused on the functioning and value of the Job Transfer Centre, which was a centre that had been established in connection with the company’s global sourcing strategy, according to which new jobs were created abroad, not in Denmark. The Job Transfer Centre assisted Novo Nordisk employees in those units that were facing staffing changes to find a new job within, or outside Novo Nordisk.

The third CSF (Appendix 9) was to ensure talent development. Similar to the previous CSF, the use and number of KPIs was consistently applied throughout the organisation. Specifically, two KPIs were used. The first was the utilisation of talent pools with respect to the filling of new or vacant VP positions. The second KPI was the results of the section of questions on an annual employee survey (eVoice) which aimed to gauge perceptions of employee development.29

The primary benefit [of the balanced scorecard] is to secure that people are aligned to the strategic goals of the company, and that they are not working for something which is not necessary to work for. We have full alignment, and that’s very convenient and comfortable.30

Eric was responsible for the 2005 DFP balanced scorecard, which had 27 KPIs: three in Finance, 12 in Business Processes, eight in People & Organisations, and four in Customers & Society, (Appendix 9 illustrates the CSFs, CSF rationale and KPIs for DFP’s 2005 balanced scorecard). There was no formal cascading of this balanced scorecard to the seven VPs. Nevertheless, each site was responsible for, and evaluated on, the majority of KPIs that were in the DFP balanced scorecard (each site is evaluated on approximately 20 KPIs).

The formal monitoring of the sites was done on a monthly basis. Specifically, data on all KPIs was calculated and updated into Novo Nordisk’s IT system (PEIS), and each site manager had to prepare a monthly report which explained any deviations from targets. Additionally, any deviation that was significantly large (gaining a red designation in the system) must be answered with a specific action plan. Eric also had informal discussions with his VPs every one to 2 months. The purpose of these meetings was to gauge how performance is proceeding. In addition to the monthly monitoring and informal discussions, Eric met each of his site managers twice a year as part of a formal Business Review. The purpose of these meetings was to discuss the monthly action plans, but also to discuss the overall site’s balanced scorecard.

In addition to being evaluated on the balanced scorecard, Eric’s (and his VPs) bonus compensation was also tied to balance scorecard performance. Appendix 10 provides Eric’s Performance Index for 2005. As shown, Eric was compensated based on 13 KPIs (two in Finance, three in Customers, six in Processes and two in People & Organisation). The weighting scheme worked as follows: if Eric achieves each target, he received a score for that KPI of 100. If he exceeded the target, then the score for the particular KPI was greater than 100; if he did not achieve the target, then the score for the particular KPI was less than 100. Each KPI score was multiplied by its respective percentage weight (e.g., 15% for Investments). The achieved index score was equal to the sum of the weighted scores across all of the KPIs. For Eric, the amount of bonus he received was 50% dependent on his achieved index score and 50% dependent on the achieved index score of Product Supply. For each VP in DFP, their bonus calculation was similar, except each VP only had ten KPIs influencing their bonus calculation. Of these ten, some were mandatory (across all sites) and some were voluntary (agreed between Eric and each VP). The voluntary KPIs tended to be related more to social objectives, as they were geared towards addressing issues which reflected the local environment. The payment of the bonus to each VP was 50% dependent on their achieved index score, and 50% dependent on the achieved index for DFP. Finally, Novo Nordisk used stretch targets in that in 2005 to receive a full bonus Eric (and his VPs) must have had an achieved index score of 105 (if targets were only hit (i.e., not exceeded) then only a 50% bonus was paid) (Appendix 11).

Conclusion

As illustrated Novo Nordisk was prime example of one organisation that included sustainability as an integrated part of its strategy, and attempts to consider it in all of its business decisions. To help managers consider sustainability in all of their business decisions, the company had adopted the Novo Nordisk Way of Management as one of their primary operating tools. Included in the Novo Nordisk Way of Management were three pillars that should help to operationalise Novo Nordisk’s corporate objectives: the facilitators, the annual (sustainability) reporting and the balanced scorecard. The significant question that remained, however, is to what extent each of these pillars was effective in influencing behaviour at the operational level.

Epilogue 2015

Ten years can seem like a lifetime. Especially when working in a dynamic business in a rapidly changing environment. Similarly, the field of research into sustainability in business practices has evolved dramatically since this case was written.

By the entry into 2015 Novo Nordisk had grown significantly and had become the most valuable company in Scandinavia, and even surpassed the Volkswagen group, measured by market capitalisation. It had enjoyed more than 10 years of double-digit sales growth, maintained competitive operating growth rates, expanded its global operations and almost doubled the number of employees. Yet, the company retained its culture and values, rooted in the Scandinavian tradition, and many of its senior managers remained in the company, albeit not necessarily in the same positions. They would often grow with the business, thereby reinforcing the values and behaviours that were seen as the right thing to do.

When the long-standing CEO, Mads Øvlisen, stepped down and left his desk to Lars Rebien Sørensen there had been concerned voices expressing doubts whether he could fill the shoes of his predecessor, and whether the strong company values would live on.

Indeed, Lars Rebien Sørensen had a rough start, faced with the South African court case, but in that situation, and in many that would follow, he demonstrated that his leadership style was formed through many years of working in the organisation. And so his intuitive reactions in times of crisis would always be consistent with the values that the company had lived by for generations: essentially these were about acting responsibly and striking the right balance, respecting the integrity of business partners and other stakeholders, fairness and good old-fashioned decency.

By 2006, Mads Øvlisen had left Novo Nordisk, but had made his mark after 34 years in the company, of which 19 years in the role as CEO. And through their partnership while he was chairman of the Board and with Lars Rebien as his CEO successor, a step was taken that would ensure the longevity of the company’s commitment to the Triple Bottom Line principle: In connection with an update of the company’s Articles of Association (the bylaws) a proposal was presented for adoption at the Annual General Meeting in 2004 to include a sentence in the clause ‘objects’: “The Company strives to conduct its activities in a financially, environmentally, and socially responsible way.” The proposal was, unsurprisingly – given the majority vote of the owner, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the broad support from both institutional and private shareholders – adopted. The Triple Bottom Line principle had been institutionalised and was as of then safeguarded, regardless of who would be in the CEO chair.

The intent was to send a very clear signal to investors and other business partners that this is how the company is managed, and will make decisions accordingly. It also specified to people working in Novo Nordisk the philosophy that would guide their decisions and actions, and emphasised the need to get the balance right, particularly when faced with difficult dilemmas.

That decision paved the way for further integration of sustainability thinking into business practices. First, the company’s reporting – which had hitherto like many other companies consisted in a financial report as the legal document and a supplementary, voluntary sustainability report – was merged into one document. This was presented to, and approved by the Board, as the logical consequence of the decision to emphasise the Triple Bottom Line in the bylaws. Some were concerned it would be the death to sustainability reporting, and with that the company’s leadership position, while others were convinced that this would be the future of corporate reporting.

In 2009 Lars Rebien Sørensen found it was time to revisit the Novo Nordisk Way of Management, which had been used since the mid-1990s as the guide for managers on the company’s values-based approach to doing business. In light of the company’s growth, particularly outside of Denmark, time had come to do a sanity check to assess if a revision was needed. He travelled to meet with employees and stakeholders in all corners of the world and came back with a strong conviction that the values were very much alive and that the Triple Bottom Line was important to employees and stakeholders alike. So he and the management team worked together to update and simplify the document that was quite lengthy, and in 2010 announced a renewed, much shorter Novo Nordisk Way. A short credo-like stosryline of the purpose and mission of the company, supplemented with 10 statements, so-called essentials, on the behaviours that should be expected of people working at Novo Nordisk. And it was emphasised that this was not intended for managers, but for every employee.

While the wording was changed, most of the contents remained, and so did the management system around it. Including the function of the facilitators to ascertain the extent to which the values are being put into action, the principles of remuneration, the stakeholder engagement approach, and the responsible business practices across the value chain. Over time, management control and reporting systems became more sophisticated, and much effort was invested in upgrading the quality of social and environmental data so they could stand the test of being represented in the Annual Report side by side with financial data that were subject to the strictest international standards for internal controls. Integration came at a cost, and a clean-up of data points was begun to ensure that data were robust and similar in scope. Social and environmental reporting became more streamlined over time, and more aligned with strategic business priorities.

In parallel with these internal changes the sustainability agenda matured, too. While originally companies would typically be pressured by stakeholder groups to adapt criticised practices that were considered harmful to people, communities or the environment, regulation took over, complemented by soft law and voluntary initiatives, often made by industry sectors rather than individual companies. Responsibility had become common practice and a floor was set for expectations of ‘good behaviour’ by companies in Denmark and abroad, not least facilitated by the growing adoption of the UN Global Compact’s principles for responsible business.

In 2010 Novo Nordisk framed a new strategy that would divert from the issues-based approach of the past decade, described in the case. Now focus would be on continuing the integration by making the business case to demonstrate how the Triple Bottom Line approach generates value – for the business and for stakeholders. As it happened, this was an act of foresight; the efforts preceded the concept of shared value articulated by Professor Michael Porter of Harvard Business School, which gained significant traction in boardrooms and business school classrooms.

The strategy was to create, capture and communicate value by using the Triple Bottom Line. To articulate an approach that combined rationales such as retaining the social contract (licence to operate), promoting smarter and more sustainable solutions (competitiveness) and experimenting with innovative and collaborative initiatives to address systemic challenges (game changers). And, most importantly, to bring it all to life in everyday practice, so that there would be consistency between ‘what we say’ and ‘what we do’. And it appeared to be successful, for as the business continued to grow, so did the company’s reputation, brand value and influence. Still, it was important to have a team to support, align and drive efforts to be a sustainable business. And, importantly, with a mandate to challenge current practices. That was, and is, the role of the Corporate Sustainability team.

Many lessons have been learnt, and although by now almost a cliché, one should be reminded that sustainability is a journey with no end destination. To Novo Nordisk, sustainable business means prospering as a result of doing business that is responsible and profitable. This is what guides decision-making, and this is what is built into the performance management and reward systems described in this case. Then and now.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely want to thank Novo Nordisk A/S for inviting us to collect data and for checking facts and figures for this case study. From Novo Nordisk we also want to thank Lito Valencia, business analyst in Finance and Business Integration, Hanne Schou-Rode, VP of Knowledge, IT & Quality in Corporate Stakeholder Relations, and Eric Drapé, SVP in Diabetes Finished Products for their time and constructive reflections. And we appreciate the valuable input to the case from professor Niels Mygind, Copenhagen Business School, Stephanie Robertson, Lene Hougaard Pedersen, Henrik Nielsen, research assistant at Copenhagen Business School, and Henrik Melgaard. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge financial support from Copenhagen Business School, London Business School and the Academy of Business in Society (ABIS).