Wine is bottled poetry.

—Robert Louis Stevenson, The Silverado Squatters (1884)

Booze-ologists may quibble over which spirit is older, beer or wine, but there’s no question that wine has inspired more rapturous poetry and prose. Great literature aside, wine has inspired a cottage industry of scribes who make their living writing exclusively about the beverage. Picture the oft-derided wine critic with the golden palate, capable of detecting hints of pencil lead, saddle leather, road tar, cigar box, cat piss, and wet dog in his glass.

Regardless of which came first, it was undoubtedly a happy accident when Stone Age hominids discovered the intoxicating properties of spoiled, or naturally fermented, fruit juice. They couldn’t possibly know that what they were drinking would ultimately stir the human imagination, grease the wheels of civilization, and become the most widely written about liquid refreshment in human history.

ANCIENT GEORGIA ON MY MIND

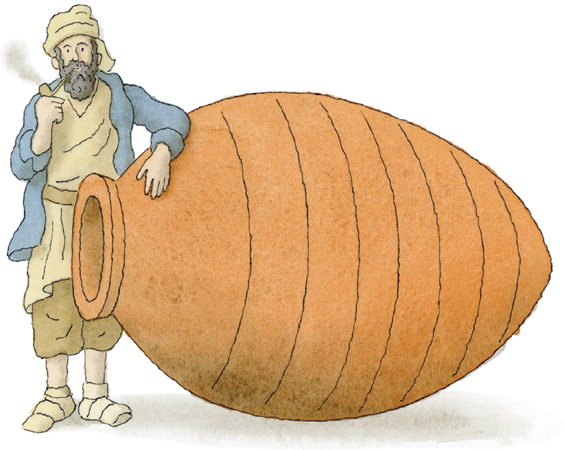

Many historians consider ancient Georgia to be the birthplace of wine. Inhabitants of the fertile valleys of the South Caucasus have been making wine for eight thousand years using an age-old method that requires no wooden barrels, vats, or monitoring systems. Instead, they used (and still use today) giant terra-cotta qvevri vessels made from Georgian clay and lined with beeswax. The pots were buried underground and filled with grapes, which were then fermented with natural yeast for two weeks and sealed for six to twelve months of aging.

The Georgian national poet, Shota Rustaveli, was among the earliest native sons to sing the praises of the region’s wines. His twelfth-century epic poem, The Knight in the Panther’s Skin (written some two hundred years before Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur), is a story of knights, friendship, chivalry, and courtly love, filled with references to the local wine culture.

Shota Rustaveli.

WILD GRAPES IN CHINESE ANTIQUITY

In ancient China, a fermented beverage using indigenous Chinese grapes appeared in the prehistoric Neolithic era, around 7000 BC, but larger-scale production of grape wine didn’t happen until the Tang dynasty (AD 618–907).

Tang dynasty silver cup.

In his poem “Xiuxi Yin,” Eastern Han dynasty poet Ruan Ji (210–263) wrote, in a testament to wine as a creative stimulant, “Once drunk, a cup of wine can bring 100 stanzas of poetry.”

Ruan Ji.

Li Bai (701–762), considered one of China’s greatest poets, wrote rapturously of wine—one of his most famous poems is entitled “Waking from Drunkenness on a Spring Day.” He would later die drunk, drowning facedown in a river while attempting to embrace the moon’s reflection.

PERSIAN WINE OF YORE

Recent excavations in Iran (ancient Persia) have uncovered pottery vessels containing tartaric acid, an indicator of the presence of wine, dating from 3100–2900 BC.

Ancient Persian drinking vessel.

According to Persian folklore, wine was discovered when a girl, despondent after being rejected by her king, attempted suicide by poisoning herself with the residue of rotted grapes. Her spirits were miraculously lifted, and the next day she reported her intoxicating discovery to the king, who duly rewarded her.

Twelfth-century Persian poet and philosopher Omar Khayyám’s verse is soaked in references to wine and the joy it brings to our fleeting existence on earth. In The Rubáiyát, the title given to a selection of his poems translated by poet Edward FitzGerald and published in 1859, Khayyam writes:

Drink wine. This is life eternal.

This is all that youth will give you.

It is the season for wine,

roses and drunken friends.

Be happy for this moment.

This moment is your life.

Omar Khayyám.

Later, in the fourteenth century, Persian Sufi poet Hafiz wrote of wine as a symbol of love and the divine. Here are several stanzas from his collection Drunk on the Wine of the Beloved: 100 Poems of Hafiz, translated by Thomas Rain Crowe:

From the large jug, drink the wine of Unity,

So that from your heart you can wash away

the futility of life’s grief.

But like this large jug, still keep the heart expansive.

Why would you want to keep the heart captive,

like an unopened bottle of wine?

With your mouth full of wine, you are selfless

And will never boast of your own abilities again.

Even though, to the pious, drinking wine is a sin,

Don’t judge me; I use it as a bleach to wash the color

of hypocrisy away.

Hafiz.

DRINKING WITH THE PHARAOHS

Viniculture dates back to 3100 BC in the Nile Delta, where wine was mostly consumed at the court of the pharaohs and by the upper classes. Members of the Egyptian ruling class were often entombed with a large stash of wine to ease the journey to the afterlife.

Chemical analysis of the residue left in a jar recovered from King Tut’s tomb indicates that he had a preference for red wine. His many wine jars were labeled with the vineyard source, the name of the chief vintner, and the year the wine was made.

The Egyptians shared their knowledge of wine with the Phoenicians, who would then spread it around the world.

ODE TO A GRECIAN FLAGON OF WINE

Wine arrived in Greece via Phoenician sailors crossing the Mediterranean around 1200 BC. It played an important role in ancient Greek culture, and its glories were extolled in verse and song. Dionysus (aka Bacchus to the Romans) was their god of the vine.

For the Greek philosophers, wine and philosophy were inseparable—the symposia were more like wine parties where philosophical discussion took place. As Plato once said, “No thing more excellent nor more valuable than wine was ever granted mankind by God.”

Wine is frequently mentioned in the work of Greek playwright Aristophanes, who considered it a boon to creativity. In his play The Knights (424 BC), the character Demosthenes requests “a flagon of wine, that I may soak my brain and say something clever.”

On the civilizing influence of wine, Thucydides, the Greek historian, observed, “The peoples of the Mediterranean began to emerge from barbarism when they learnt to cultivate the olive and the vine.”

Thucydides.

IN VINO VERITAS

Ancient Roman wine jug.

The Roman Empire picked up where the Greeks left off, perfecting the winemaking process and establishing virtually all the major wine-producing regions that exist in western Europe today. They were the first to use barrels (borrowed from the Gauls) and glass bottles (borrowed from the Syrians), rather than earthenware vessels, for storage and shipping.

The Roman poet Virgil, writing down instructions to wine growers, dispensed a key bit of advice that still holds today: “Vines love an open hill.”

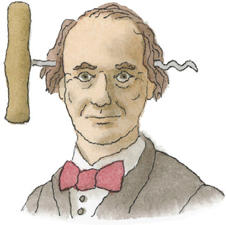

Pliny the Elder, the first-century naturalist and author of the thirty-seven-volume encyclopedia Naturalis historia, wrote extensively on viticulture, including a ranking of the “first growths” of Rome, and introducing the concept of terroir (that a particular region’s climate, soil, and terrain imparts unique characteristics to the taste of a wine). Pliny is also the source of the most famous Latin proverb on wine: “In vino veritas” (In wine there is truth).

Pliny the Elder with Roman drinking horn.

Horace, the Roman poet, was devoted to wine. When contemplating his death, he expressed more heartache over departing from his wine cellar than from his wife. Regarding poetic inspiration, he wrote, “Poems written by water drinkers will never enjoy long life or acclaim.”

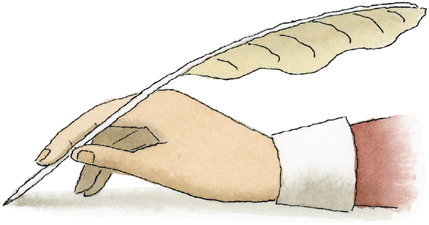

THE MERRY BARD OF AVON

In William Shakespeare’s England (1564–1616), wine was very expensive—about twelve times more costly than ale, the drink of the masses—and typically enjoyed only by the upper classes. England’s climate was not suitable for growing grapes, so most of its wine was imported from France, Spain, and Greece. Sack, a sweet wine fortified with brandy (akin to modern-day sherry) was also very popular during the Elizabethan era.

Little is known of Shakespeare’s personal drinking habits, but as a man of means, he could undoubtedly afford to drink something other than ale. By all accounts, he was not the sodden party animal of his contemporary Christopher Marlowe, but the frequent wine cameos in his work suggest he probably enjoyed it. His characters cite many more wine varieties—muscatel, Rhine, Bordeaux, canary, and malmsey—than they do ale or beer.

VIVE LE VIN FRANÇAISE!

France, blessed with soil and climate conditions ideally suited for viticulture, has long reigned as the world’s greatest purveyor of fine wine (only to be challenged in the latter half of the twentieth century by California). Its two predominant wine regions, Bordeaux and Burgundy, produce some of the most famous and expensive wines that we consume today.

During a visit to Bordeaux in 1787, Thomas Jefferson—America’s first wine connoisseur—placed orders for 24 cases of Château Haut-Brion, 250 bottles of Château Lafite, and an unspecified amount of Château d’Yquem.

Thomas Jefferson.

In 1855, Emperor Napoleon III suggested a classification system in Bordeaux to identify the region’s best wines. Known as the Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855, the rankings established so-called first through fifth growths and remain largely unchanged to this day.

Emperor Napoleon III.

Modern Bordeaux and Burgundy lovers can be counted among the literary elite . . .

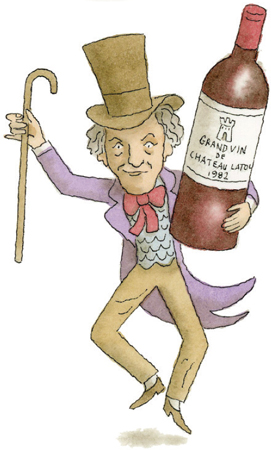

British author Roald Dahl, of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964) fame, made wine the subject of a short story that appeared in The New Yorker in 1951. “Taste” is the tale of a bet on wine vintages at a London dinner party. Dahl was an avid wine collector with a keen interest in Bordeaux and Burgundy, and a particular obsession with Bordeaux from 1982 (regarded by many as the greatest vintage of modern times).

Roald Dahl.

Comic novelist and New Yorker contributor Peter De Vries called himself a “winebibber” and was especially enamored of the wines of Burgundy: “The masculine Montrachet and the feminine Musigny offer the most exquisite communion with earth, air and sky open to man.” The witticism “Write drunk, edit sober,” which seems to have gone viral, is often attributed to Ernest Hemingway. But in fact it can be traced to De Vries. A character in his novel Reuben, Reuben (1964) says, “Sometimes I write drunk and revise sober, and sometimes I write sober and revise drunk. But you have to have both elements in creation.”

Peter De Vries.

THE MACABRE OENOPHILE

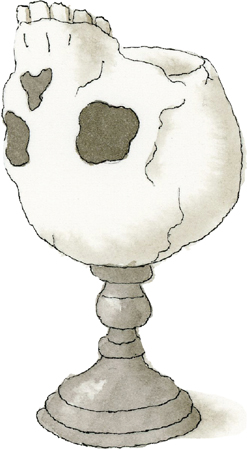

The nineteenth-century poet Lord Byron, author of the satiric poem Don Juan (1819), is known for having fashioned a drinking vessel out of a human skull that his gardener uncovered at his ancestral home, Newstead Abbey, in Nottinghamshire, England. He was borrowing a tradition dating back to Gaulish chieftains using Roman skulls as drinking goblets. Byron sent the well-preserved skull to town and reported that “it returned with a very high polish, and of a mottled colour like tortoiseshell.”

Byron had a poem inscribed on the side of the skull, prosaically titled “Lines Inscribed Upon a Cup Formed from a Skull.” In it, he meditates on the mind’s nobler purpose in death—as a bony receptacle from which the living can enjoy the splendors of claret (the British term for red wine from Bordeaux): “And when, alas! our brains are gone, What nobler substitute than wine?”

Lord Byron.

THE ADDLED OENOPHILE

When not exploring altered states of consciousness in opium dens or hashish clubs, Charles Baudelaire, the French poet, essayist, and art critic, always defaulted to wine as his intoxicant of choice.

Charles Baudelaire.

In his 1851 essay “Du vin et du haschish” (“On Wine and Hashish”), he asks, “Who has not known the profound joys of wine? Everyone who has ever had remorse to appease, a memory to evoke, a grief to drown, a castle in Spain to build—in short, everyone—has invoked the mysterious god hidden in the fibres of the vine.”

NASCENT NAPA VALLEY

In 1880 the soon-to-be famous Scottish author of Treasure Island (1883), Robert Louis Stevenson, honeymooned in Napa Valley. In The Silverado Squatters (1884), an account of his time there at the dawn of California’s wine industry, he describes the trial-and-error process of planting grapes: “Wine in California is still in the experimental stage. . . . One corner of land after another is tried with one kind of grape after another. This is failure; that is better; a third best. So, bit by bit, they grope about for their Clos Vougeot and Lafite.”

Robert Louis Stevenson.

DAVID VERSUS GOLIATH: The Judgment of Paris

A Franciscan missionary, Father Junípero Serra, planted California’s first sustained vineyard at Mission San Diego de Alcalá in 1779. Following the publication of The Silverado Squatters, the state’s wine industry had been on a long, slow climb toward respectability, with sporadic triumphs along the way.

Father Junípero Serra.

But the pivotal turning point in the history of California wine would occur on May 24, 1976. In the so-called Judgment of Paris, a wine competition organized by a British wine merchant, a cluster of California upstart wines dethroned their renowned Bordeaux and Burgundy counterparts in a blind tasting. In a blow to French wine supremacy, Napa Valley had arrived as one of the world’s great wine regions.

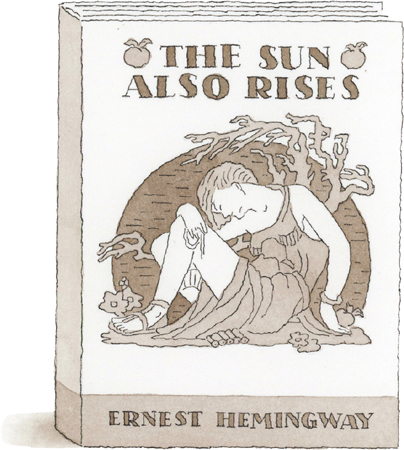

PAPA AND THE GRAPE

Ernest Hemingway is arguably the most iconic literary figure in booze lore. Hemingway was—to use a term that H. L. Mencken originally coined for himself—“ombibulous.” He drank everything and enjoyed it all.

Following the horrors of World War I, many disillusioned American writers, feeling that the arts had become increasingly underappreciated at home, emigrated to Europe as part of the “Lost Generation.” Hemingway was among them, arriving in Paris in 1921 to work as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star. It was here, in close proximity to Bordeaux and Burgundy, that his introduction to fine wine likely occurred.

In A Moveable Feast (1964), his memoir of life in Paris, he recounts a meal at home with his then wife, Hadley, in which, too poor to eat out, they drink “Beaune from the co-operative.” Beaune is the capital city of Burgundy, France’s great wine region. And it’s likely that even Beaune from a Parisian co-op was not half-bad.

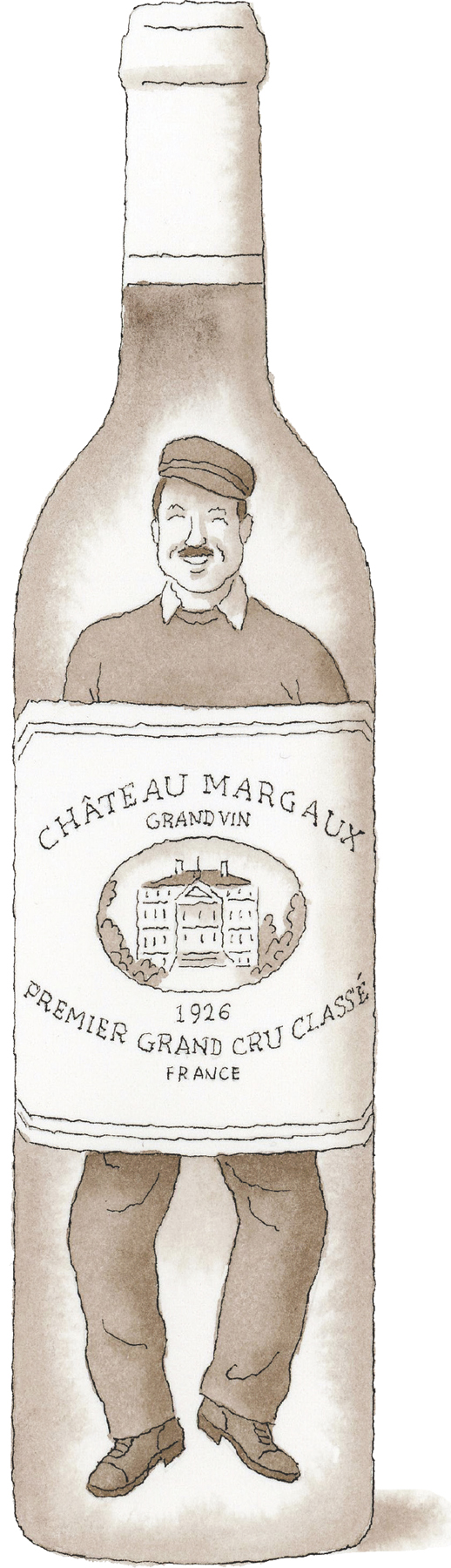

The prodigious drinking that occurs in his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises can be viewed as Hemingway’s repudiation of Prohibition in the United States. The story’s narrator, American expatriate Jake Barnes, and his circle of friends travel from Paris, France, to Pamplona, Spain, to watch the running of the bulls and the bullfights. In chapter 15 alone, seven liters of wine are shared between three people.

Hemingway and his characters didn’t mind the slower pace and fewer complications of drinking alone, either. At one point Jake says, “I drank a bottle of wine for company. It was a Château Margaux. It was pleasant to be drinking slowly and to be tasting the wine and to be drinking alone. A bottle of wine was good company.”

The classic French laguiole pocketknife with a corkscrew has been in use since 1880.

In his paean to Spanish bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon (1932), Hemingway writes: “Wine is one of the most civilized things in the world and one of the most natural things of the world that has been brought to the greatest perfection, and it offers a greater range for enjoyment and appreciation than, possibly, any other purely sensory thing.”

HAVE WINE, WILL TRAVEL

Many writers with a taste for adventure have fallen prey to wine’s allure. British author D. H. Lawrence traveled extensively throughout Italy, France, Mexico, the United States, and Australia, sampling wines along the way. But the author of Lady Chatterley ’s Lover (1928) did not love all that he tasted, and he could be an unforgiving critic. He once described a Spanish wine as “the sulphurous urination of some aged horse.”

D. H. Lawrence.

James Joyce’s favorite wine was Fendant de Sion, a fruity Swiss white made from the Chasselas grape. He must have discovered the varietal while living off and on in Zurich, Switzerland, where he wrote much of Ulysses (1922) and would later finish writing Finnegans Wake (1939).

James Joyce.

In Finnegans Wake, he likens the wine to the urine of an archduchess (apparently high praise!), referring to it in Joycean code as “Fanny Urinia.”

M. F. K. Fisher, the doyen of American food writing and author of How to Cook a Wolf (1942), spent four years as a young woman living in Dijon, France, the culinary capital of Burgundy. There she was inculcated with the glories of French food and wine.

Fisher could be effusive on the subject of wine. In the preface to The University of California/Sotheby Book of California Wine (1984) she writes: “I can no more think of my own life without thinking of wine and wines and where they grew for me and why I drank them when I did and why I picked the grapes and where I opened the oldest procurable bottles, and all that, than I can remember living before I breathed.”

M. F. K. Fisher.

The French novelist Marguerite Duras was born abroad. The daughter of two teachers, she spent her childhood in French Indochina (now Vietnam) before returning to her parents’ native country at age seventeen. Duras has said that she wrote her popular novel The Lover (1984) when she was drunk. Speaking to the New York Times in 1991, she commented on alcohol’s role in her daily routine, “I drank red wine to fall asleep. . . . Every hour a glass of wine and in the morning Cognac after coffee, and afterwards I wrote. What is astonishing when I look back is how I managed to write.”

BUKOWSKI’S BROMANCE

In a 1994 interview with Transit magazine, Charles Bukowski declared, “As a young man, I hung around the libraries during the day and the bars at night.” When asked to describe his ideal conditions for writing, he responded, “Between 10 p.m. and 2 a.m. Bottle of wine, smokes, radio on to classical music. I write 2 or 3 nights a week.”

Charles Bukowski.

In Ham on Rye (1982), his alter ego, Henry Chinaski, extolls the virtues of intoxication: “Getting drunk was good. I decided that I would always like getting drunk. It took away the obvious and maybe if you could get away from the obvious often enough, you wouldn’t become obvious yourself.”

When times were lean, Bukowski drank cheap beer, whiskey, or vodka. But when flush with royalty checks, he switched to fine red wine. Good wine was, according to Bukowski, “blood of the gods . . . the best for creation. You can write three or four hours.”

Bukowski had long maintained a writing crush on John Fante, an obscure writer who had garnered critical acclaim with his early novels set in Los Angeles. But Fante’s work, first published in the 1930s, never found an audience, and the author spent much of his life working in Hollywood as a screenwriter. As a young man, Bukowski had discovered Fante’s books in the Los Angeles Public Library, and they were revelatory. “Fante was my god,” he said.

Fante’s reputation enjoyed a renaissance after Bukowski sent a copy of Ask the Dust (1939) to his editor, John Martin, at Black Sparrow Press. Martin was so impressed that he set out to republish all of Fante’s works, starting with Ask the Dust in 1980.

Bukowski’s last “typer,” an IBM Selectric.

Wine, an integral part of Fante’s Italian American upbringing, figured heavily in his work. He described his novel The Brotherhood of the Grape (1977) as “the story of four Italian wine drunks from Roseville, a tale revolving around my father and his friends.”

The downtown LA dive bar frequented by both Bukowski and John Fante.

THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT SHERRY

Sherry has a small, but fervent, following among certain writers . . .

The fortified white wine from Andalusia, Spain, plays a titular role in Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Cask of Amontillado” (1846). The unhinged narrator lures an unwitting victim into his home for a sip of the wine, intent on killing him over a perceived slight that happened fifty years before. Amontillado is a darker sherry variety hailing from the Montilla region of Spain.

Sherry, mixed with hot tea, was Carson McCullers’s drink of choice. The author of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1940) dubbed the concoction a “Sonnie Boy.” So as not to be conspicuous, she drank it from a thermos throughout the day while working at her typewriter. Her thermos was a constant companion during her most productive years.

Carson McCullers.

American poet and memoirist Maya Angelou, acclaimed for her 1969 autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, was also a fan. In a 1983 interview she enumerated her essential items for a successful writing session: “I keep a dictionary, a Bible, a deck of cards and a bottle of sherry in the room.”

Maya Angelou.

THE NOVELIST AS WINE WRITER

Jay McInerney, best known for Bright Lights, Big City (1984), has parlayed his passion for the grape into a sideline as a respected, if unorthodox, wine writer. Injecting new life into an increasingly stilted body of wine criticism, he has written monthly wine columns for House & Garden and Town & Country magazines. In his collection of essays, A Hedonist in the Cellar: Adventures in Wine (2006), he writes that “fermented grape juice is a far more potent catalyst for contemplation and meditation than a highball. . . . It is a sacramental beverage, a sacred and symbolic liquid.”

He often eschews the usual floral descriptors in favor of cultural references. He’s more apt to equate wine with authors and thespians than with sandalwood and pencil lead: “Bordeaux was my first love. . . . But increasingly I’m drawn to its rival Burgundy, the Turgenev to Bordeaux’s Tolstoy, and when I’m looking for sheer power and exuberance and less finesse, to the Dostoyevskian southern Rhône.”

McInerney on California Syrah: “Syrah . . . keeps threatening to become a California star, but so far its career has been a little like that of the actor Orlando Bloom, more promising than happening.”

McInerney’s beloved Château Haut-Brion: “the first growth of poets and lovers.”

THE GLORIES OF BACCHUS

What is it about wine, relative to other spirits, that has inspired such a disproportionate amount of hand-scrawled veneration? Part of its allure, aside from taste bud friendliness (it’s certainly easier to like than stronger, throat-scorching distillates), may be its inscrutability. Wine mutates in the bottle. Every wine is a moving target. The same sublime Châteauneuf-du-Pape you drank seven years ago might be plonk today. And as widely consumed as it is, no alcoholic beverage intimidates like wine—the sheer number of grape varietals, styles, and wine regions is bewildering. Thankfully, an ancillary industry of “experts” is out there to help, from wine critics who advise on the best bottles to buy to restaurant sommeliers whose highly trained noses will help you sniff out what to drink with your dinner.

Perhaps McInerney encapsulates the mystique of the beverage best when he writes that wine “can provide intellectual as well as sensual pleasure; it’s an inexhaustible subject, a nexus of subjects, which leads us, if we choose to follow, into the realms of geology, botany, meteorology, history, aesthetics, and literature.”