I leant against the bar, between an alderman and a solicitor, drinking bitter. . . . I liked the taste of beer, its live, white lather, its brass-bright depths, the sudden world through the wet brown walls of the glass, the tilted rush to the lips and the slow swallowing down to the lapping belly, the salt on the tongue, the foam at the corners.

—Dylan Thomas, “Old Garbo,” Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog (1940)

1940s cone-top beer can.

Unlike other spirits that have been up and down the socioeconomic ladder over the centuries, buffeted by history and changing tastes, beer has largely remained true to its working-class roots. Beer is most commonly made from malted barley, which is heartier and less susceptible to the whims of nature—bad weather and pest infestations—than the grapevine, making it easier, and cheaper, to produce.

Vintage brass bottle opener circa 1930s.

As such, beer has never enjoyed the exalted reputation of wine, and there hasn’t been the ink devoted to it that there has been to its vinous cousin. But its origins reach back just as far, and it is the most widely consumed beverage in the world after water and tea. Some would even argue that the complexity and sophistication of a modern microbrew can rival that of a fine wine.

EARLY BEER: AMBER WAVES OF SPOILED GRAIN

Beer’s beginnings likely coincided with the early transition of nomadic tribes to grain-based agrarian societies, likely going as far back as 10,000 BC. Some scholars have even suggested it was the advent of beer that turned early humans from foragers to farmers. The discovery of natural fermentation, which led to beer being brewed from cereal grains like barley, as well as wheat, corn, and rice, was undoubtedly accidental—the consequence of moist baked bread starting to spoil. In its earliest form, it was made with water and malted grain that was slowly fermented, or brewed. Hops would be introduced centuries later as a preserving agent and flavor enhancer.

Barley.

From antiquity to the late nineteenth century, beer was often a safer alternative to the unsanitary water from rivers and streams, and consequently consumed by men, women, and children alike.

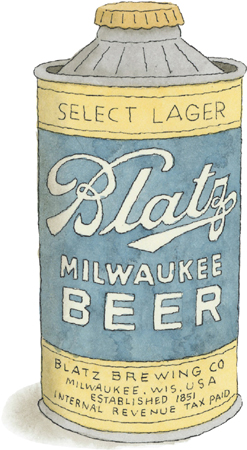

Ancient Mesopotamian gold beer cup with drinking spout.

SUMERIAN SUDS

Archeological evidence of barley beer production dates back to the Sumerians of ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iran), between 3500 and 3100 BC. Cuneiform texts found at the Godin Tepe settlement, along the ancient Silk Road trading route, feature numerous pictographs of beer.

To filter out barley hulls and other debris, ancient Sumerians drank beer through straws made from gold or reeds.

The Epic of Gilgamesh (2700 BC), a Sumerian poem that is often considered the earliest surviving work of great literature, provides the first written account of beer as a source of merriment. In the poem a wild man named Enkidu is educated in the ways of men by Shamhat, a prostitute:

“Eat the food, Enkidu, it is the way one lives.

Drink the beer, as is the custom of the land.”

Enkidu ate the food until he was sated,

He drank the beer—seven jugs!—and became

expansive and sang with joy!

The Hymn to Ninkasi (circa 1800 BC) is an ode to the Sumerian goddess of beer, and includes a description of the brewing process. Literacy was uncommon at the time, and thus singing the hymn was a way to memorize and disseminate the recipe. The priestesses of Ninkasi are generally regarded as history’s first brewers. Women were typically responsible for brewing in the home and often worked as tavern keepers as well. All levels of society consumed the beverage.

Ninkasi.

In the Old Testament’s book of Genesis, Noah took measures to ease the boredom of forty days and forty nights of rain. His provisions list for the ark included barrels of Sumerian beer.

THE BEER-AMIDS

In ancient Egypt, beer similarly soaked through the fabric of daily life. Laborers received beer rations three times a day and were often compensated with beer for their work. And as in Mesopotamia, brewing was largely the provenance of women.

Like the Sumerians, the Egyptians regarded beer as a gift from the gods and believed that human beings had been taught to brew by the god Osiris. An inscription in the Dendera Temple complex from 2200 BC reads, “The mouth of a perfectly contented man is filled with beer.”

HISTORY’S FIRST INSUFFERABLE WINE SNOBS

Both the ancient Greeks and Romans liked to deride beer as inferior to its beloved grape-based counterpart. Writing about the German predilection for beer, the Roman historian Tacitus could barely contain his contempt, “To drink, the Teutons have a horrible brew fermented from barley or wheat, a brew which has only a very far removed similarity to wine.”

Despite this snobbery, beer was still widely consumed in ancient Greece and Rome. The Greek playwright Sophocles advocated a daily diet of bread, meat, green vegetables, and beer. Excavations of an AD 179 Roman military encampment built by Marcus Aurelius on the Danube have uncovered evidence of large-scale beer brewing.

Sophocles.

ZICKE, ZACKE, ZICKE, ZACKE, HOI, HOI, HOI

The Germans began brewing beer as early as 800 BC, but it wasn’t until the Christian era that the beverage truly flourished. In the early Middle Ages, beer production in Europe became centralized in monasteries and convents. This provided not only hospitality for traveling pilgrims but also sustenance for monks during fasting.

Around AD 1150, German monks introduced hops to the brewing process, thus creating the revolutionary precursor to modern beer. Hops (the flowers of the hop plant), added a spiky, citric bitterness to counter the sweetness of the malt.

The German beer stein, with its hinged lid, originated in the fourteenth century following the bubonic plague and a series of insect invasions. By the early 1500s, German law required beverage containers to be covered as a sanitary measure.

JOHN BARLEYCORN

“John Barleycorn” is an English folk song of unknown origins that dates back to the sixteenth century. The titular character is a metaphor for barley. The song details Barleycorn’s suffering and death at the hands of the farmer and the miller, corresponding to the different stages of barley cultivation (sowing, reaping, and malting). In death, this sacrificial figure is resurrected and his body, or blood, consumed in the form of beer and whiskey. Some scholars suggest that “John Barleycorn” was a pagan analog of Christian transubstantiation.

English ceramic “John Barleycorn” jug, circa 1934.

Many versions of “John Barleycorn” exist, but the most famous may be the ballad by Scottish poet Robert Burns, penned in 1782. In the final stanzas of the poem, he seems to be referring to beer, whiskey, or both:

John Barleycorn was a hero bold,

Of noble enterprise;

For if you do but taste his blood,

’Twill make your courage rise.

’Twill make a man forget his woe;

’Twill heighten all his joy;

’Twill make the widow’s heart to sing,

Tho’ the tear were in her eye.

Then let us toast John Barleycorn,

Each man a glass in hand;

And may his great posterity

Ne’er fail in old Scotland!

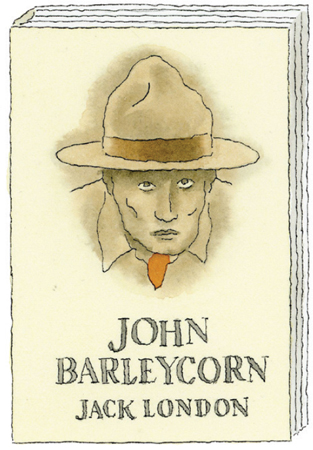

In 1913, Jack London would borrow “John Barleycorn” as the title for what he dubbed his “alcoholic memoirs,” which chronicle both his love of drinking and his struggles with it: “He is the august companion with whom one walks with the gods. He is also in league with the Noseless One [death].”

The first edition in its original dustwrapper.

London writes of getting drunk for the first time at the age of five, drinking beer from a bucket he was carrying to his stepfather at work in the fields. By the time he was in his teens, he could drink most men under the table. Early in his career as a writer, he refused to drink until he had written his thousand words a day. But that resolve slowly deteriorated, along with his health, over time. Later he had trouble writing without a drink, or as he called it, being “pleasantly jingled.”

Jack London: portrait of the artist as a young beer drinker.

London floridly describes his inebriated state: “As I say, I was lighted up. In my brain every thought was at home. Every thought, in its little cell, crouched ready-dressed at the door, like prisoners at midnight waiting a jail-break. And every thought was a vision, bright-imaged, sharp-cut, unmistakable. My brain was illuminated by the clear, white light of alcohol. John Barleycorn was on a truth-telling rampage, giving away the choicest secrets on himself. And I was his spokesman.”

THE BREWMASTER OF HAMPSHIRE COUNTY

Jane Austen was not only a beer drinker but a brewer as well. Brewing was deemed a household duty for women in eighteenth-century England, and Austen likely learned the process as a teenager from her mother while growing up in the Hampshire village of Steventon. In a letter to her sister, Cassandra, in 1808, Austen writes: “It is you, however, in this instance, that have little children, and I that have the great cask, for we are brewing spruce beer again.” Translation: You bring the kids, I’ve got the refreshments.

Spruce beer was akin to root beer (traditionally made from the roots and bark of the sassafras tree) but flavored instead with the buds, needles, and roots of the spruce tree, and containing hops and molasses. The Austen family clearly enjoyed their alcoholic beverages—they also brewed mead, a beer variation made by fermenting honey with water, and made wine.

Austen’s brew makes an appearance in her novel Emma (1815): “He wanted to make a memorandum in his pocket-book; it was about spruce-beer. Mr. Knightley had been telling him something about brewing spruce-beer.”

Austen’s exact recipe has unfortunately been lost to history, but the Jane Austen Centre in Bath, England, offers an approximation:

Jane Austen’s Spruce Beer

5 gallons water

⅛ pound hops

½ cup dried, bruised gingerroot

1 pound outer twigs of spruce fir

3 quarts molasses

½ yeast cake dissolved in

½ cup warm water

In a large kettle, combine the water, hops, gingerroot, and spruce fir twigs. Boil together until all the hops sink to the bottom of the kettle. Strain into a large crock and stir in the molasses. After this has cooled, add the yeast. Cover and leave to set for 48 hours. Then bottle, cap, and leave in a warm place (70–75°F) for five days, after which it will be ready to drink. Store upright in a cool place.

CRAFT BREWS: HOPPY DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN

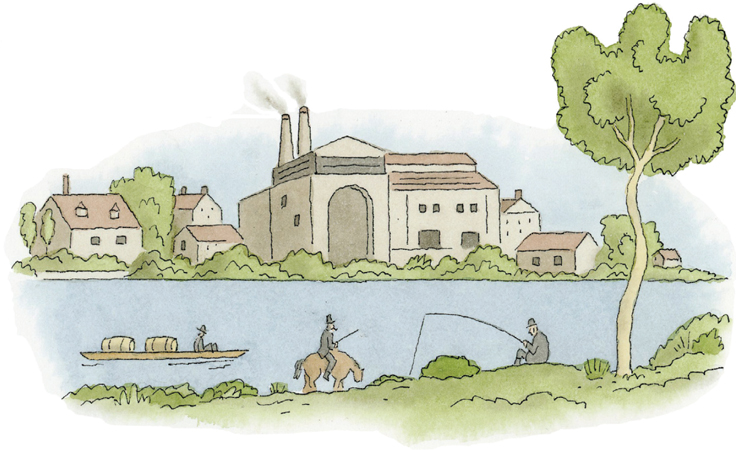

The catalyst for the American craft-brewing revolution of the latter quarter of the twentieth century, a movement that would fundamentally alter the course of the beer industry, was the resurrection of an all-but-forgotten beer style—India pale ale, better known as IPA. Today’s hop freaks owe an enormous debt of gratitude to Englishman George Hodgson, the eighteenth-century brewer widely credited for its creation.

George Hodgson.

The London brewery Hodgson’s of Bow was founded in 1752 and situated on the river Lea, a convenient location for supplying beer to the East India Company’s fleet at Blackwall on the river Thames. The East India Company was an English trading concern and chief provider of beer, and other goods, for the British Empire in the East. In the 1780s, Hodgson’s revelation was to add dry hops as a preserving agent to the finished beer barrels, which helped prevent spoilage during the six-month sea voyages to the colonies in India. The sturdy new brew was dubbed India pale ale.

British author William Makepeace Thackeray came by his fondness for IPA naturally—he was born in India, where his father happened to work for the East India Company. He name-checks Hodgson’s of Bow in his satirical novel set in colonial India, The Tremendous Adventures of Major Gahagan (first serialized in 1838): “It amused him, he said, to see me drink Hodgson’s pale ale (I drank two hundred and thirty-four dozen the first year I was in Bengal).”

In the 1820s, Samuel Allsopp created his own version of Hodgson’s “India ale.”

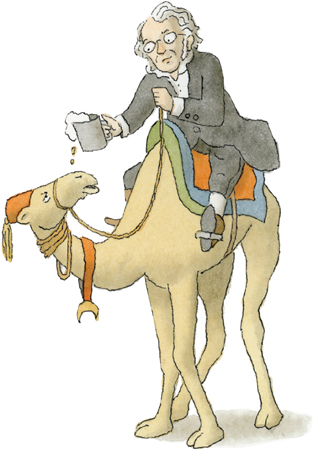

Thackeray also alludes to Hodgson’s in his most famous novel, Vanity Fair (1848), when an East India Company employee, Jos Sedley, imbibes “some of the ale for which the place is famous.” And in his Notes on a Journey from Cornhill to Cairo (1846), Thackeray was ecstatic to discover “a camel-load of Hodson’s [sic] pale ale from Beyroot [sic].”

William Makepeace Thackeray.

By the late nineteenth century, the advent of industrial refrigeration killed much of the IPA’s raison d’être. Hops were no longer necessary for increased shelf life, giving way to the light lager styles that would gain favor and predominate for the next hundred years. However, hops would later return with a vengeance, in the form of America’s craft brewing boom. West Coast breweries vying to out-hop one another would result in double and triple IPAs.

Hop flower.

VICTORIAN ERA “BOTTLED WATER”

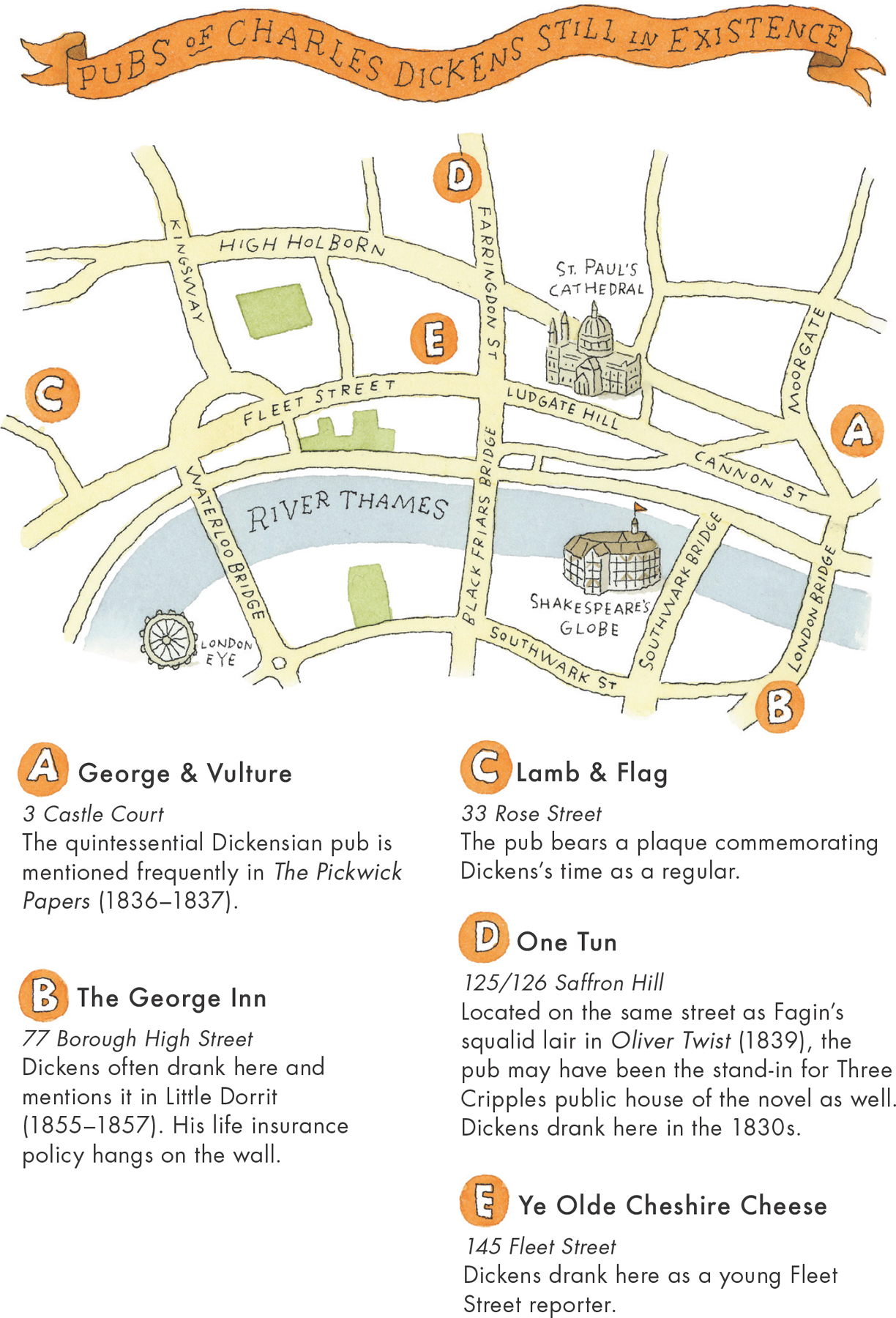

The novels of Charles Dickens, the great social chronicler of his age, are suffused with beer, pub, and brewery references. Children in the nineteenth century, as reflected in Dickens’s novels, drank “small beer” or “table beer,” as a less toxic alternative to the unsanitary water of the Thames. The butler in Dombey and Son (1848), when serving sickly Paul Dombey junior “sometimes mingled porter with his table beer to make him strong.” In David Copperfield (1850) the boy hero and narrator speaks of “going into the bar of a strange public-house for a glass of ale or porter.” In Great Expectations (1861) Miss Havisham has inherited her wealth from her father, who had owned and operated a brewery.

Charles Dickens.

DORCHESTER ALE

Thomas Hardy’s beloved hometown of Dorchester, the setting for many of his novels, was renowned for its particularly strong ales. Hardy’s appreciation for the beverage is evident in numerous passages from his work.

Dust jacket of the Modern Library edition (1950).

The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886) mentions a recipe (brew-speak dictionary required!) for the kind of home-brewed ale made in the country pubs of Hardy’s Wessex:

15 pounds pale-ale malt (M & F from England)

2 pounds light brown sugar

Hops: Chinook for boil, circa 25 HBU

Fuggles for finish, circa 1 ounce 2 mins.

Chinook ⅛ dry hop

Fuggles ¼ dry hop

Mash: 15 quarts water

Mash in 130, raise to 158°F. Hold for 1½ hours.

Sparge with 30 quarts at 170°F. Add 1 teaspoon gypsum.

Boil about 6 hours. Add bittering hops 60 minutes before the end of the boil.

Wort should be 3.5–4 gallons gravity, gravity 1.30–1.145

Yeast: 1028 w yeast.

After 7 days, rack into 5 gallon carbouy and pitch champagne yeast.

Let ferment 4–6 days, then rack into 30 gallon carbouy.

If you don’t have one, flush a 5 gallon with dry ice to remove oxygen.

Dry hop with hop bag for 2 weeks.

Remove hop bag, let sit an additional month.

Bottle: There may be a little carbonation. Add some champagne yeast when bottling.

Use corn sugar to prime: About ⅓ cup.

Thomas Hardy.

In 1968, Eldridge Pope Brewery in Dorchester, which first opened its doors in 1831, released a Thomas Hardy’s Ale (at 11.7 percent alcohol by volume—the strongest beer produced in England at the time) to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of the British author’s death. Printed on the label was Hardy’s description of a strong Wessex ale from his novel The Trumpet-Major (1880): “It was the most beautiful colour that the eye of an artist in beer could desire; full in body, yet brisk as a volcano; piquant, yet without a twang; luminous as a autumn sunset; free from streakiness of taste; but, finally, rather heady.”

THE TALL-TALE HEART

A poem known as “Lines on Ale” (1848) has been attributed, perhaps apocryphally, to Edgar Allan Poe. As the story goes, Poe wrote the poem at the Washington Tavern in Lowell, Massachusetts, to settle his bar tab, and the “original” copy hung on the wall of the tavern until about 1920. However, some scholars believe the tale to be a hoax foisted on the public by a mischievous bartender.

LINES ON ALE

Fill with mingled cream and amber,

I will drain that glass again.

Such hilarious visions clamber

Through the chamber of my brain—

Quaintest thoughts—queerest fancies

Come to life and fade away;

What care I how time advances?

I am drinking ale today.

STOUT FRIENDS

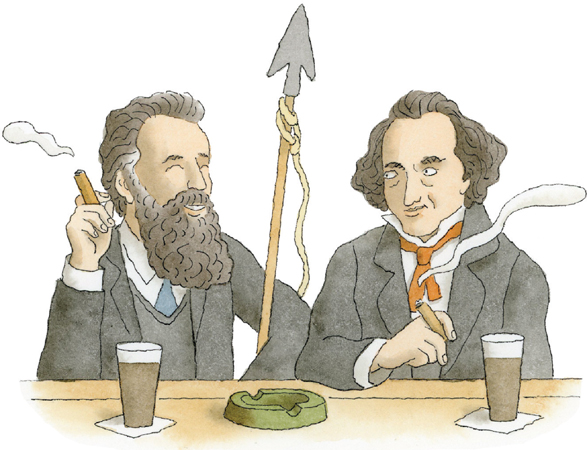

Moby-Dick (1851) author Herman Melville clearly enjoyed the social bond among drinkers. Based on journal entries of both men starting in 1850, he and Nathaniel Hawthorne, of The Scarlet Letter (1850) fame, developed a convivial relationship over many drinking sessions.

Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

In 1856 Melville visited Hawthorne, who was living in England after being appointed US consul in Liverpool. In a journal entry dated November 10, after traveling together by train to Southport, Melville wrote, “An agreeable day. Took a long walk by the sea. Sand & grass. Wild and desolate. A strong wind. Good talk. In the evening Stout & Fox & Geese.” Fox & Goose was a local pub.

After exploring a cathedral in Chester on November 15, Hawthorne writes in his own journal that the two men “sat down in a small snuggery, behind the bar, and smoked cigars and drank some stout.”

Stout, or porter, originated in London in the early 1700s. It’s a dark beer typically made with unmalted barley roasted in a kiln.

THE BOOZE CRUSADER

H. L. Mencken, the caustic American journalist and social critic, was a staunch defender of alcohol during Prohibition, asserting that it was the drys, not the drinkers, who were the real savages. “Pithecanthropus erectus was a teetotaler, but the angels, you may be sure, know what is proper at 5 p.m.”

H. L. Mencken.

1920s temperance poster.

He enjoyed all manner of alcoholic drinks, but beer was his passion, and Czech pilsner was his gold standard. At one point he made a pilgrimage to Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, declaring it “home of the best beer on earth and hence one of the great shrines of the human race.”

Pilsner Urquell, introduced in 1842, is the original Czech pilsner.

GUINNESS IS GOOD FOR YOU

Since its beginnings in 1759, when a thirty-four-year-old Arthur Guinness signed a nine-thousand-year lease on a run-down property at St. James’s Gate in Dublin, Guinness stout has remained one of the most iconic brews in all of beerdom. Forget the bottle or the can—Guinness on tap is the only way to drink it. Any well-versed beer drinker is familiar with the time-honored serving ritual. A proper pour means filling the pint glass two-thirds full. The bartender then walks off, allowing it to “surge and settle” for a few minutes, before returning to fill it the rest of the way. The customer drinks only when the line between the foamy head and the black beer has achieved peak contrast.

Statue of Arthur Guinness in his hometown of Celbridge in County Kildare.

James Joyce, whose own preference for wine has already been noted, called Guinness “the wine of the country” and made numerous references to the Guinness family and Ireland’s national drink in his work.

In Ulysses (1922) the Guinness brewery is a passing thought in the mind of Leopold Bloom: “Be interesting to get a pass through Hancock to see the brewery. Regular world in itself. Vats of porter, wonderful. Rats get in too. Drink themselves big as a collie floating. Dead drunk on the porter.” Joyce also mentions the great-great-grandsons of Arthur, Lord Ardilaun and Lord Iveagh.

The unadorned first edition of the controversial novel published in 1922 by Sylvia Beach in Paris.

In Finnegans Wake (1939), “A Visit to Guinness’ Brewery” is listed among the essay topics for the Earwicker children, Shem, Shaun, and Issy.

The St. James’s Gate entrance to the Guinness Brewery.

Legend has it that Joyce submitted his own idea for an advertising slogan to the company—“Guinness—the free, the flow, the frothy freshener”—but like so many booze anecdotes, this story has been discredited. In a 2011 article in James Joyce Quarterly, Catherine Gubernatis Dannen concludes that the story was concocted for a 1982 Guinness advertisement to capitalize on the connection between the Guinness Company and the “Joyce Industry.”

James Joyce.

Nonetheless, it’s unlikely they would have replaced their already familiar slogan, “Guinness is good for you.” In Finnegans Wake, Joyce writes, “Let us find that pint of porter place . . . Benjamin’s Lea . . . and see the foamous homely brew, bebattled by bottle—then put James’s Gate in my hand.” He also puns on the famous slogan with the phrase “Genghis is ghoon for you.”

Guinness poster, 1929.

THE BEER MILKSHAKE AND GOD’S VOICE

In John Steinbeck’s 1945 novel Cannery Row, the main character, Doc, loves beer so much that somebody comments, “Someday [he’ll] go in and order a beer milkshake.”

Doc obsesses about the idea and eventually gets up the nerve to order one, making up a recipe for the server on the spot. “Put in some milk, add half a bottle of beer. Give me the other half in a glass—no sugar in the milkshake.” Steinbeck’s bit of tomfoolery proved prescient—seventy years later, beer shakes could be found on chain-restaurant menus.

John Steinbeck.

The American Pulitzer Prize–winning writer Anne Sexton, a pioneer of confessional poetry, favored martinis but enjoyed a beer with lunch. She opens her poem “For Eleanor Boylan Talking with God” (1962) with the line:

God has a brown voice,

as soft and full as beer.

MEN AND BEER

Nobody knows for sure what biological or social factors play into beer’s overwhelmingly male appeal. Some taste scientists maintain that women have higher taste sensitivities and are less tolerant of bitterness. Society has also decreed that it’s not “manly” to drink sweet and fruity “girly drinks.” Strangely, Hemingway, the prototypical manly man, didn’t pay much attention to beer. Going against type, he even enjoyed fruity cocktails like the daiquiri, albeit without the sugar.

A few beer-swilling alpha males:

In his 1947 crime novel I, the Jury, Mickey Spillane introduced the world to detective Mike Hammer. Among hard-boiled gumshoes, Hammer was an aberration—unlike his whiskey-swilling compatriots, he favored beer. In later novels Hammer drank Miller Lite (which Spillane just happened to be a pitchman for).

Mickey Spillane.

Norman Mailer, author of The Naked and the Dead (1948), describing his workday in a 1964 interview with The Paris Review, said, “In the afternoon, I usually needed a can of beer to prime me.”

When times were lean, Charles Bukowski would default to beer. In 1988, Life magazine asked some noted scientists, theologians, artists, and authors to ponder the meaning of life. Bukowski’s response:

For those who believe in God, most of the bigger questions are answered. But for those of us who can’t readily accept the God formula, the big answers don’t remain stone-written. We adjust to new conditions and discoveries. We are pliable. Love need not be a command or faith a dictum. I am my own God. We are here to unlearn the teachings of the church, state and our education system. We are here to drink beer.

Charles Bukowski (at right).

RUSSIAN HOPS

Russian poet and novelist Boris Pasternak, best known for Doctor Zhivago (1957), expressed obeisance to beer’s distinguishing ingredient in his love poem “Hops” (1953):

Beneath the willow wound round with ivy,

We take cover from the worst

Of the storm, with a greatcoat round

Our shoulders and my hands around

your waist.

I’ve got it wrong. That isn’t ivy

Entwined in the bushes round

The wood, but hops. You intoxicate me!

Let’s spread the greatcoat on the ground.

—translated by Jon Stallworthy and Peter France

Boris Pasternak.

ALL WORK AND NO BEER MAKES JACK A DULL BOY

The American master of horror and suspense Stephen King loved his suds but mostly drank at home. Now sober, he told The Guardian in 2013, “I didn’t go out and drink in bars, because they were full of assholes like me.”

Stephen King.

He regards his most famous book, The Shining (1977), as a confession. The story, about a drunken father who wants to kill his own kid, grew out of his own feelings of antagonism toward his children when he was drinking. Writing the book was a way to get it out of his system.

The 1980 paperback edition featuring art from the Stanley Kubrick movie poster.

During King’s drinking days, he revealed in Writer’s Digest, “I like to write when I’m drunk. I’ve never had any particular problem writing that way, although I never wrote anything that was worth a dime while under the influence of pot or any of the hallucinogenics.” In those days he considered drinking a boon to his craft: “Writers who drink constantly do not last long, but a writer who drinks carefully is probably a better writer,” King has said.

B IS FOR BEER

When American novelist Tom Robbins, author of Even Cowgirls Get the Blues (1976), saw a Frank Cotham cartoon in The New Yorker with the caption “I doubt that a children’s book about beer would sell,” he decided to take up the challenge.

The result was B Is for Beer (2009), which, in Robbins’s own words, helped give kids “a clearer understanding of why their dad keeps a second refrigerator in the garage, and why he stays up late out there on school nights with his shirt off, listening to Aerosmith.” The book undoubtedly appealed to adults as well and has gone on to sell a respectable 45,000 copies.

IN BEER WE TRUST

Today beer aficionados are luxuriating in a golden age of brewing. With increasingly complex and offbeat offerings, modern microbrewers continue to push the limits of what beer can be, moving it farther and farther away from the insipid lagers of yore. Among the quirky selections that an intrepid beer adventurer might encounter on modern liquor store shelves: avocado honey ale, pizza beer, doughnut chocolate peanut butter banana ale, coconut curry hefeweizen, bacon coffee porter, and oyster stout (as in bull testicles).

Beer snobs (previously an oxymoron) now have reason to rejoice. Modern brews have been quietly ascending to the rarified heights usually reserved for fine wine and whiskey. Cicerones, the beer equivalent of wine sommeliers, are now happy to pair your Buddha bowl with the perfect organic sour beer, and many restaurants now tout beer-tasting menus.

Venerated American sci-fi author Ray Bradbury was—true to form—ahead of his time when he summed up the beverage’s highbrow/lowbrow appeal in his 1955 short story collection, The October Country, writing, “Beer’s intellectual. What a shame so many idiots drink it.”

A cicerone.