Bourbon does for me what the piece of cake did for Proust.

—Walker Percy, Esquire (1975)

In drink lore few beverages can rival the colorful history or the pop-culture cachet of whiskey (aka whisky, bourbon, and scotch). The distilled spirit, made from grain mash, conjures images of feral Scottish Highlanders, grizzled western gunslingers, and hard-boiled detectives. Its literary bloodlines also run deep—the list of writers who have enjoyed the stuff is longer than any other spirit included in this volume.

THE WATER OF LIFE

The art of distillation, or the process of vaporizing and condensing a liquid to remove impurities and arrive at its essence, may have begun as early as 2000 BC in China, Egypt, or Mesopotamia. Over the millennia, distilling techniques spread to Europe, and somewhere between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries made their way to Scotland and Ireland via peripatetic monks. Scottish and Irish monasteries, lacking the proper climate for grape cultivation and wine production, turned to fermenting and distilling mash made from locally available grains, and whiskey was born. Scotland and Ireland still argue over who was first.

The Talisker Distillery on the Isle of Skye, Scotland, founded in 1830.

The term whisky derives from the Gaelic uisge beatha, meaning “water of life.” The English modified it to whiskybae, and it was quickly shortened to whisky. Whisky is the spelling used in Scotland and Canada, and whiskey is used in Ireland and America.

THE TIPSY SCOTTISH BARDS

Scotch, as whisky from Scotland would come to be known, would soon be embraced as the country’s national drink. Not surprisingly, it was consumed and adored by the country’s national poet, Robert Burns. According to legend, he took his first sip of uisge beatha at the age of twenty-two in the coastal town of Irvine in North Ayrshire, where he had moved to learn the trade of flax combing.

Robert Burns.

In his poem ”Scotch Drink” (1785), Burns cites the spirit as inspiration:

O thou, my muse! Guid auld Scotch drink!

Whether thro’ wimpling worms thou jink,

Or richly brown, ream owre the brink

In glorious faem,

Inspire me, till I lisp an’ wink,

To sing thy name!

A Scottish quaich, or traditional “friendship” drinking vessel, dating back to the sixteenth century and used by Highland clan chiefs to share whisky.

Fellow Scotsman Sir Walter Scott, author of such classic novels as Ivanhoe (1820) and Rob Roy (1817), was equally enamored of his native drink. As Scotch whisky historian Iain Russell writes, Scott “saw good Scotch whisky as a noble drink and an integral part of the idealized Highland culture that provided the inspiration for much of his writing.”

Sir Walter Scott.

Scott’s novel Waverley (1814), acknowledged as the first historical novel in the Western tradition, tells the story of a callow English soldier posted with his regiment to Scotland during the Jacobite uprising of 1745. There he is introduced to the heroic traditions, and whisky, of the Scottish Highlanders:

“The allowance of whisky, however, would have appeared prodigal to any but Highlanders, who, living entirely in the open air and in a very moist climate, can consume great quantities of ardent spirits without the usual baneful effects either upon the brain or constitution.”

Scottish Highlander.

Peat-cutting spade—smoke from peat is often used during the malting process to enhance a Scotch whisky’s character.

THE POWER AND THE GLORY OF SCOTCH

Twentieth-century writers across the pond were no less enthused by the drink of their ancestors.

Graham Greene, the preeminent British novelist, enjoyed J&B scotch whisky and soda. One of Greene’s most famous, and controversial, characters is the nameless “whisky priest” in his novel The Power and the Glory (1940). Originally published in an edition of 3,500 copies, the book is generally regarded as his masterpiece. Set in Mexico in the 1930s, the novel depicts the priest ministering to his impoverished flock while under a haze of alcohol and fear brought on by government suppression of the Catholic Church.

Graham Greene’s favorite scotch.

One of literature’s most famous drinking scenes occurs in Greene’s Our Man in Havana (1958). The novel’s protagonist, James Wormold—hapless vacuum cleaner salesman by day and master spy by night—engages an adversary in a game of checkers. He uses mini-bottles from his whiskey collection as game pieces—whiskey is on one side, bourbon on the other. “When you take a piece you drink it,” Wormold explains. The whiskeys name-checked are Johnnie Walker Red, dimpled Haig, Cairgorm, and Grant’s. The bourbons are Four Roses, Kentucky Tavern, Old Forester, and Old Taylor.

Kingsley Amis’s appreciation for all manner of spirits is well documented, yet he held a special place in his heart for scotch. In his paean to booze, Every Day Drinking (1983), he declares: “Scotch Whisky is my desert-island drink. I mean not only that it’s my favorite, but that for me it comes nearer than anything else to being a drink for all occasions and all times of day, even with meals.”

Amis, a prolific writer, was not averse to drinking while pecking away at the typewriter. In an interview with The Paris Review in 1975 he remarked, “So alcohol in moderate amounts and at a fairly leisurely speed is valuable to me—at least I think so. It could be that I could have written better without it . . . but it could also be true that I’d have written far less without it.”

Kingsley Amis’s Adler Universal 39 typewriter.

Relative to many of his sodden contemporaries, James Joyce was a lightweight, but nonetheless he enjoyed whiskey in addition to the aforementioned wine and beer. Writing of Joyce’s proclivity for only drinking at night, his biographer Richard Ellmann remarked, “He engaged in excess with considerable prudence.”

A particularly Joycean anecdote: The writer, in failing health and stung by the underwhelming response to early drafts of Finnegans Wake, considered enlisting the aid of a coauthor in case he was unable to finish the novel himself. A prime candidate was James Stephens, not because he was best qualified but because the book cover could display their initials together—JJ&S—just like his favorite brand of Dublin whiskey—John Jameson & Son.

James Joyce’s preferred brand of whiskey.

Brendan Behan, the Irish republican poet, novelist, and playwright, consumed vast quantities of Irish whiskey, and other libations, during his brief lifetime (he died from alcohol-related causes in 1964 at age forty-one). He was a self-described “drinker with a writing problem,” and the subject of the Pogues’ song “Streams of Whiskey.”

THE WHISKEY DIASPORA IN AMERICA

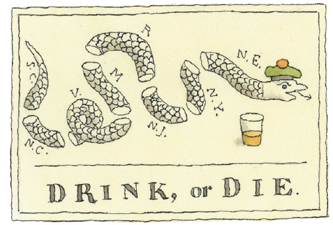

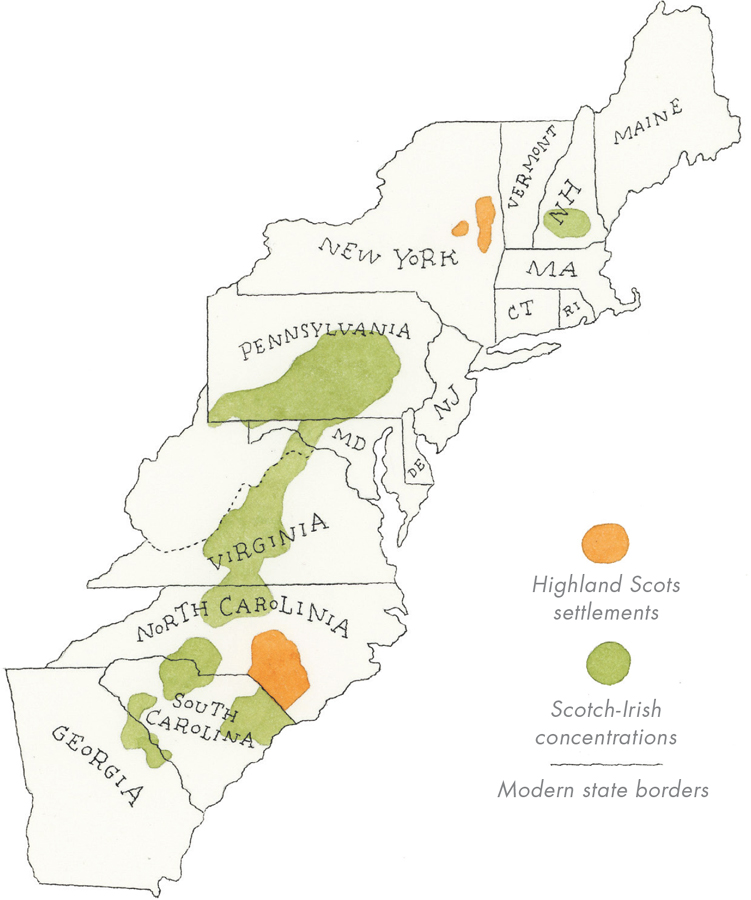

Many Scottish and Irish immigrants arrived in America during the seventeenth century to settle in the colonies, bringing their whiskey distillation know-how with them. Whiskey quickly became a valuable commodity and was used as currency during the American Revolutionary War.

Scottish and Scotch Irish immigration to America, 1700–1800.

In 1791, Alexander Hamilton imposed a federal excise tax on whiskey to help pay down the Revolutionary War debt, prompting Scottish and Irish immigrant farmers in Pennsylvania to stage an uprising dubbed the Whiskey Rebellion. Tax collectors were attacked and in some cases whipped, tarred, and feathered. By 1794, the rebellion was quelled by government militia under orders from President George Washington. The tax remained until 1802, when it was repealed by President Thomas Jefferson.

During the Whiskey Rebellion, tax collectors were tarred and feathered by farmers and distillers.

SOUTHERN COMFORT

The most popular form of American whiskey is bourbon, and its birthplace is the American South. To be called bourbon, the spirit must be produced in the United States, aged in new oak charred barrels, and made from a grain mixture that includes at least 51 percent corn.

Barrel charring breaks down the oak’s hemicellulose into sugars that are then caramelized, imparting to bourbon its distinctive flavor.

It’s generally accepted that the name bourbon came from Bourbon County in upstate Kentucky in the nineteenth century. However, bourbon historian and author Michael Veach traces the moniker’s origin to New Orleans and two men known as the Tarascon brothers. Arriving in Louisville around 1807 by way of the Cognac region of France, they began shipping local whiskey down the Ohio River to Louisiana’s port city. Demand grew for “that whiskey they sell on Bourbon Street,” which eventually became “that bourbon whiskey.”

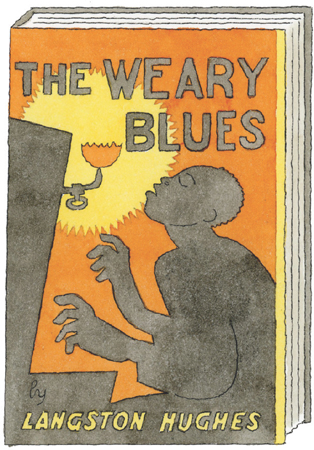

Corn whiskey, a variation made from a mash of at least 80 percent corn, was enjoyed and celebrated by the American poet, playwright, and novelist Langston Hughes, born in Joplin, Missouri. His “Hey-Hey Blues” appeared in the pages of The New Yorker in 1939:

Cause I can HEY on water,

I said HEY-HEY on beer,

HEY on water,

And HEY-HEY on beer,

But gimme good corn whiskey

And I’ll HEY-HEY-HEY—and cheer!

Langston Hughes.

Hughes’s debut poetry collection was published in 1926, during Prohibition, when he was twenty-four years old.

More than a few other southern scribes partook of the local hooch, including Louisiana novelist Walker Percy, author of The Moviegoer (1961). He appreciated the aesthetic of bourbon drinking, particularly knocking it back neat. In an article he wrote for Esquire in 1975, simply titled “Bourbon,” Walker praised the use of the spirit to “warm the heart, to reduce the anomie of the late twentieth century, to cure the cold phlegm of Wednesday afternoons.”

Walker Percy.

WHISKEY’S POET LAUREATE

William Faulkner, the southerner and celebrated Nobel laureate who declared, “Civilization begins with distillation,” was in a league of his own, and may have been whiskey’s greatest literary champion.

William Faulkner.

Born in New Albany, Mississippi, on September 25, 1897, Faulkner grew up in Oxford and would remain in the region, the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, where all of his novels were set, for most of his life.

Faulkner’s relationship to drink began in 1918, when his high school sweetheart, Estelle Oldham, married another man. Faulkner was heartbroken and turned to the bottle. He relocated briefly to New Haven, Connecticut, to stay with Philip Stone, a family friend and Yale graduate, who would become the young writer’s mentor, introducing him to the work of James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and T. S. Eliot.

Faulkner attended the University of Mississippi (“Ole Miss”) for just three semesters, receiving a D in English, before dropping out. During this period he was reportedly downing a quart of bourbon a day. Seven years later, in 1926, he published his first novel, Soldier’s Pay, which was well received. It contains the line “What can equal a mother’s love? Except a good drink of whiskey.”

Colonel Reb, Ole Miss’s controversial mascot, was retired in 2003.

In 1929 he learned that Estelle was divorcing after ten years of marriage, and she and Faulkner were married two months later, in June.

Estelle Oldham.

Later that same year his first major novel, The Sound and the Fury, was published. The jigsaw puzzle narrative and post-Joycean stream-of-consciousness technique made for difficult reading, but the book would later be hailed as a masterpiece.

1929 first edition published by Jonathan Cape & Harrison Smith.

In 1930, as Faulkner continued to drink heavily, his second acclaimed novel, As I Lay Dying, was published. Faulkner readily admitted to drinking while he worked. As he would later explain to his French translator, Maurice Edgar Coindreau: “You see, I usually write at night. I always keep my whiskey within reach; so many ideas that I can’t remember in the morning pop into my head.”

Hemingway, known for his disciplined separation of work and drink, once said of Faulkner, “I can tell right in the middle of the page when he’s had his first one.”

One of the central characters in Light in August, Faulkner’s epic 1932 novel set in the American South during Prohibition, was a whiskey bootlegger named Joe Christmas. In this passage Faulkner eloquently describes the act of drinking whiskey: “The whiskey went down his throat cold as molasses. . . . Then the whiskey began to burn in him . . . while thinking became one with the slow, hot coiling and recoiling of his entrails.”

That same year, to help pay the bills, Faulkner headed to Hollywood to work part-time as a screenwriter for MGM—a dalliance with Tinseltown that would continue for decades.

In an interview the director Howard Hawks recalled meeting the writer over a “couple quarts of whiskey” to discuss writing the screenplay that would become Today We Live, a 1933 hit movie starring Gary Cooper and Joan Crawford. Other screen credits would include To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946).

Original one-sheet movie poster.

During his increasingly frequent forays to Hollywood, Faulkner’s favorite hangout was the Musso & Frank Grill, where he was known to order Old Grand-Dad bourbon.

One of Bill’s many bourbons.

In 1936, Absalom, Absalom! was published, today widely regarded as his greatest novel. While visiting the Algonquin Hotel in New York City in 1937, a sozzled Faulkner passed out against a steam radiator, severely burning his back. When asked about his work, he would say, “Hell, how do I know what it means? I was drunk when I wrote it.”

The Algonquin incident.

In 1950, Faulkner received the Nobel Prize in Literature. Five years later he would receive the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for his novel A Fable. By then, his bourbon consumption was rationalized as “treatment” for his various maladies, including sore throats, a bad back, and general malaise.

A Faulkner tobacco pipe manufactured by Digby of London.

In 1962 he was awarded a second Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Reivers, only to die of a heart attack a month later at the age of sixty-four. A fitting epitaph would have been his prescription for a successful day of work: “The tools that I need for my trade are simply pen, paper, food, tobacco, and a little whiskey.”

THE MINT JULEP

William Faulkner certainly enjoyed whiskey straight (Jack Daniel’s and Old Crow were favorites), and a toddy—hot or cold—was a frequent companion, but his signature drink was the mint julep.

The word julep derives from the ancient Persian gulab, a rose-petal-flavored water (more commonly known in the West today as rosewater) still used in food, drinks, perfume, cosmetics, and religious ceremonies. In the Mediterranean, indigenous mint replaced the rose petals, and the drink eventually made its way to the New World, where, in the American South, it was combined with bourbon.

Since 1938, the cocktail has been a prominent feature of the Kentucky Derby, and in 1983 it became the horse race’s official drink. Each year, roughly 120,000 juleps are served at the race over the course of two days.

Faulkner loved the drink so much that he had his own simple recipe for it, displayed on a typewritten notecard at his Rowan Oak estate in Oxford, Mississippi: whiskey, 1tsp sugar, ice, mint served in a metal cup. A more precise version follows:

Faulkner’s Mint Julep

Leaves from 4 to 5 mint sprigs, plus sprig for garnish

1 tablespoon sugar

2 teaspoons water

Crushed ice

2½ ounces bourbon

In a metal julep cup or highball glass, gently muddle mint leaves after removing stems. Add sugar and water and fill with crushed ice. Add bourbon and garnish with a mint sprig.

A REAL-LIFE JAY GATSBY

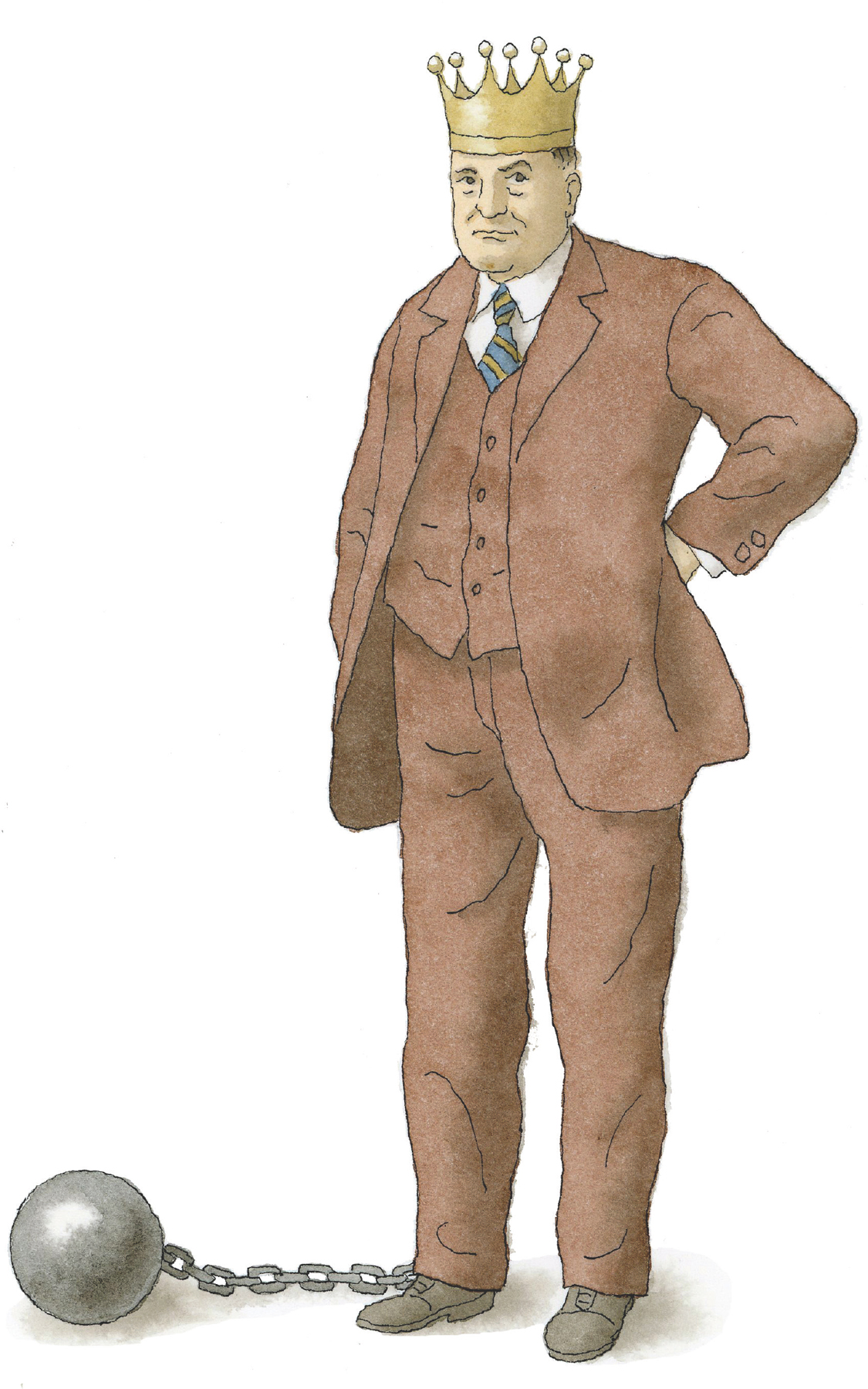

During Prohibition, one of America’s most notorious whiskey bootleggers was George Remus, known for his peculiar habit of referring to himself in the third person. Remus, a Midwest criminal defense lawyer, scoured the Volstead Act looking for loopholes that would enable him to buy and sell stockpiles of bonded whiskey (government-licensed “medicinal” whiskey available with a doctor’s prescription). He discovered that by owning distilleries and wholesale drug companies, he could legally buy and sell large quantities of alcohol and then divert them for illegal sale.

George Remus.

With organized crime controlling most of Chicago, Remus moved to Cincinnati, where 80 percent of America’s bonded whiskey was located. He quickly became enormously wealthy but was eventually caught and convicted in 1921. “The King of the Bootleggers” may have been an inspiration for Jay Gatsby, the title character in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby (1925). Fitzgerald purportedly met him by chance at a hotel in Louisville and was captivated by his larger-than-life personality.

WHISKEY SOUR

In 1925 in France, Ernest Hemingway, a fledgling writer who had yet to write his first novel, met F. Scott Fitzgerald, an established literary star three years his senior. In his Parisian memoir, A Moveable Feast (1964), Hemingway recounts an episode involving whiskey sours. Fitzgerald, feeling unwell, is convinced he’s catching “congestion of the lungs,” or pneumonia. An exasperated Hemingway tries to calm him down: “‘Look, Scott,’ I said, ‘You’re perfectly O.K. If you want to do the best thing to keep from catching cold, just stay in bed and I’ll order us each a lemonade and whisky.’”

He summons a waiter and orders two citron pressés (pressed lemon juice) and two double whiskeys. Fitzgerald is soon feeling better. They proceed to drink two more rounds before Fitzgerald passes out and is carted off to bed.

In his description, Hemingway, never fond of sweet drinks, omits the sweetener typically included in the cocktail’s ingredients to offset the bitterness of the lemon.

Traditional Whiskey Sour

2 ounces whiskey (bourbon)

⅔ ounce freshly squeezed lemon juice

1 teaspoon superfine sugar (or ¾ ounce simple syrup)

1 egg white (optional)

Cracked ice

Maraschino cherry or lemon wedge for garnish

Shake the whiskey, juice, sugar, and egg white (if using), well with cracked ice. Strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with a maraschino cherry or lemon wedge.

HARD-BOILED AND THREE SHEETS TO THE WIND

Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett were two whiskey-loving founders of the so-called hard-boiled school of detective fiction. Chandler’s archetypal character Philip Marlowe, a private detective who appeared in many of his stories, always kept a bottle of Old Forester in his office. Chandler once said, “There is no bad whiskey. There are only some whiskeys that aren’t as good as others.” Dashiell Hammett’s most famous detective character, Sam Spade, was also a whiskey man. In The Maltese Falcon (1930), he drinks a Manhattan cocktail (whiskey, sweet vermouth, and bitters) from a cup. Hammett’s fifth and final detective novel, The Thin Man (1934), was published only months after the repeal of Prohibition. It was eagerly embraced by a public ready to drink, and scotch perfumes its pages from beginning to end.

The Maltese Falcon.

For thirty years American dramatist, screenwriter, and polemicist Lillian Hellman maintained a tumultuous on-and-off relationship with Hammett. On the strength of two successful plays she wrote in the 1930s, The Children’s Hour (1934) and The Little Foxes (1939), Hellman became the first woman to gain access into the exclusive all-male club of American playwrights.

Lillian Hellman.

And she was no slouch as a boozer—she enjoyed drinking scotch neat out of a wineglass. Whiskey was typically considered a man’s drink, but Hellman was one of several notable exceptions. As was her longtime friend Dorothy Parker, who settled on scotch as her drink of choice after flirtations with gin martinis and champagne.

Dorothy Parker.

PANDORA IN BLUE JEANS

In the mid-1950s an unknown, bedraggled housewife from New Hampshire with a penchant for whiskey would shock the American public with her debut novel, which became an explosive best seller and one of the most controversial novels of the twentieth century. It would spawn a movie and a long-running television soap opera. It was Peyton Place by Grace Metalious. Metalious would become wealthy and famous overnight, as well as an unwitting feminist trailblazer, inspiring women all over America who were chafing under the restrictive social norms of the Eisenhower era.

Born into poverty on September 8, 1924, in the mill town of Manchester, New Hampshire, as Marie Grace DeRepentigny, Metalious was of French Canadian ancestry. She was raised in a ramshackle cottage near the Merrimack River, the same river that flowed south through Lowell, Massachusetts, the hometown of French Canadian Jack Kerouac.

Grace Metalious.

Metalious’s parents separated when she was eleven, and words were her refuge from a troubled home. At eighteen, despite dreaming of a different life for herself, she married her high school sweetheart, George Metalious, and settled into her presumptive roles as homemaker and mother-to-be.

The couple later settled in Gilmanton, New Hampshire, where George had been offered a position as a school principal, eventually having three children. Metalious focused seriously on her writing, often working up to fourteen hours a day while shirking her domestic responsibilities.

Her writing area was always immaculate, but the rest of the house was a pigsty, and her children were often neglected.

Metalious was the antithesis of the demure New England housewife: she smoked, drank whiskey, used salty language, and wore baggy flannel shirts and jeans, all of which drew sidelong glances from her incredulous neighbors. She drank to deal with her emotional isolation. Her favorite watering hole was the Tavern Hotel in the nearby town of Laconia (a model for Peyton Place), where she enjoyed Canadian Club whiskey with ginger ale and a lemon twist.

By the spring of 1955, Metalious had the first draft of a manuscript, with the working title The Tree and the Blossom, but it was rejected by all the major publishers for its racy content. It eventually landed on the desk of Kitty Messner, the president of Julian Messner, Inc. Messner loved everything about the book except the title and wanted it changed to the name of the town where the novel was set—Peyton Place. At age thirty-two, Metalious had a book deal. The novel, published in 1956, was an instant sensation and turned her into a celebrity overnight. It chronicled the dark secrets and sinister machinations lurking beneath the placid surface of a seemingly respectable New England town. Its lurid depictions of sex, rape, public drunkenness, murder, incest, abortion, and suicide imperiled the Norman Rockwell–like image of 1950s New England.

1956 first edition published by Messner.

Critical reviews were mostly negative, with one notable exception—the New York Times Book Review praised Peyton Place for taking a stand “against the false fronts and bourgeois pretensions of allegedly respectable communities.” To cope with the pressures of her newfound fame and notoriety, Metalious started plowing through multiple packs of unfiltered Parliaments a day and drinking heavily.

Grace’s 1951 white Cadillac convertible.

For the inhabitants of Gilmanton, the novel struck too close to home. Grace was threatened with libel lawsuits, her kids were harassed, and George lost his job. Her marriage soon cracked under the pressure. The scandalous book was condemned by sanctimonious politicians and denounced from the pulpit. Metalious defended herself: “To talk about adults without talking about their sex drives is like talking about a window without glass.”

The remaining seven years of Grace’s short life would be a whirlwind of lavish spending, Hollywood parties, numerous affairs, and copious amounts of whiskey. Having gone through most of her money, Grace went on to grind out three more novels before succumbing to cirrhosis of the liver at age thirty-nine. Toward the end, doctors believed she had been drinking a fifth of whiskey every day.

Peyton Place remained on the New York Times best-seller list for fifty-nine weeks, making it the top-selling novel of the twentieth century, just ahead of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind (1936).

SCOTCH VERSUS BOURBON: THE YANKEE WHISKEY CONNOISSEUR

The American writer, adventurer, and irascible humorist Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known by his nom de plume, Mark Twain, was a devotee of his native spirit, American bourbon (Old Crow being his favorite)—until he discovered scotch whisky.

Mark Twain.

During a trip across the Atlantic to England in 1873, he was introduced to a scotch and lemon juice cocktail. Captivated by the beverage, he wrote home to his wife, Livy, from the Langham Hotel in London: “Livy my darling, I want you to be sure & remember to have in the bathroom, when I arrive, a bottle of Scotch whisky, a lemon, some crushed sugar, and a bottle of Angostura bitters.”

The beloved author of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) would eventually start drinking his scotch neat, enjoying it in tandem with his pipe or cigars, and calling it “my pet of all brews.”

HITTING THE BOTTLE WITH GENE, NORM, AND MR. GONZO

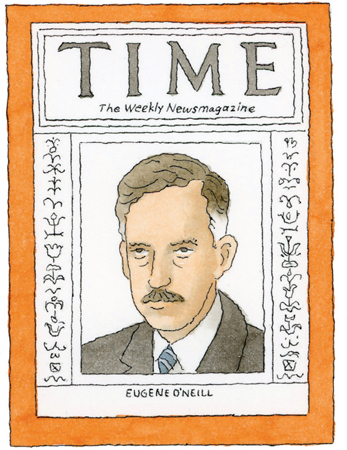

The prolific playwright Eugene O’Neill is exhibit A for the case that writing and drinking, though not necessarily at the same time, enhance productivity. Anointed “America’s Shakespeare,” he drank whiskey like a fish—and produced sixteen new plays in his first decade of writing professionally. Along the way he managed to land on the cover of Time and collect a Nobel Prize in Literature and three Pulitzers.

O’Neill on the cover of Time magazine, February 13, 1928.

He wrote what he knew—his work is filled with alcoholic lowlifes. In The Iceman Cometh (1939), his whiskey-swilling alter ego, Jimmy, professes, “I discovered early in life that living frightened me when I was sober.”

The pugnacious novelist Norman Mailer had little to say on the subject of alcohol when queried about it, but his reputation as an inveterate boozer was well known. He enjoyed bourbon but never scotch: “I’m an American writer, I drink bourbon, an American drink. . . . That’s the difference between a great writer and someone who’ll never be a great writer—someone who knows the difference between Scotch and bourbon.”

Norman Mailer.

For Hunter S. Thompson, the “gonzo journalist” and author of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1972), mind alteration was a way of life—booze, marijuana, LSD, amyl nitrite, cocaine, ether, and mescaline all found their way into his system. But like Twain, he had a deep appreciation for both bourbon and scotch—Wild Turkey to write and Chivas Regal scotch to read the morning papers. He called Chivas on the rocks his “snow cone.” Thompson’s advice for fledgling party animals: “Sleep late, have fun, get wild, drink whiskey and drive fast on empty streets with nothing in mind but falling in love and not getting arrested. . . . Res ipsa loquitur. Let the good times roll.”

Hunter S. Thompson.

THE MOST COMPLEX SPIRIT ON EARTH

Throughout recorded history, whiskey has remained a hard-liquor stalwart, impervious to fluctuating booze fashions. For drinkers who prefer their liquor neat, the clear spirits—vodka and gin—simply can’t compete with a premium whiskey’s Technicolor assault on the nose and tongue. Unlike whiskey, vodka and gin don’t age, a necessary precondition for olfactory and taste bud nirvana.

The quality and breadth of whiskey offerings available today is mind-boggling. The traditional whiskey-producing countries no longer have an exclusive claim to the title “best in the world.” It’s difficult to imagine what Robert Burns would have made of modern Japanese single-malts that consistently beat those from Scotland in blind taste tests.

George Bernard Shaw, who wasn’t actually much of a drinker, may have summed up the spirit’s universal appeal best when he declared, “Whiskey is liquid sunshine.”