One martini is all right, two is too many, three is not enough.

—James Thurber, Time magazine (1960)

Juniper berry.

Gin has probably sparked more literary inspiration than any liquid distillate other than whiskey, but it wasn’t always the respectable, civilized spirit that it is today. Social critics in eighteenth-century Georgian England regarded it as a plague on society—the crack cocaine of its day. In the early nineteenth century the advent of cocktails, or “mixed drinks,” in London helped rehabilitate gin’s lowly reputation.

In America, Prohibition paradoxically helped spur the Roaring Twenties—the sodden era of flappers, jazz, and art deco that followed World War I. It was a glamorous decade, when the writing life and the drinking life merged powerfully, ushering in a golden age of hard-drinking men and women of letters. Gin would be a big part of it.

DUTCH COURAGE

Gin derives its distinctive piney scent and flavor from Juniperus communis, also known as the juniper berry.

The spirit’s murky origins can be traced back to the sixteenth-century lowlands of Belgium and Holland. Genever, the Dutch ancestor to modern gin, was initially sold in chemist shops for its medicinal properties. It was used to treat a host of ailments, including gout and gallstones.

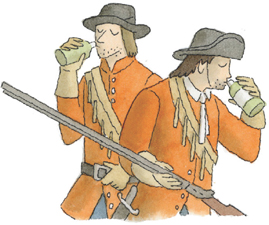

British troops fighting in the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) were given Dutch gin to warm their bodies in the cold weather and to calm their nerves before battle. The soldiers dubbed it “Dutch courage.”

Plague doctors in the seventeenth century wore beak masks (the origin of the term quack) filled with crushed juniper berries, believed to protect against the epidemic.

William of Orange, ruler of the Dutch Republic, did much to popularize the spirit in England during his occupation of the British throne starting in 1689. During his reign he boycotted imports of brandy, a popular fortified wine from archenemy France. This opened the floodgates for Dutch distillers, who were soon shipping boatloads of genever to England as quickly as they could produce it.

THE LONDON GIN CRAZE

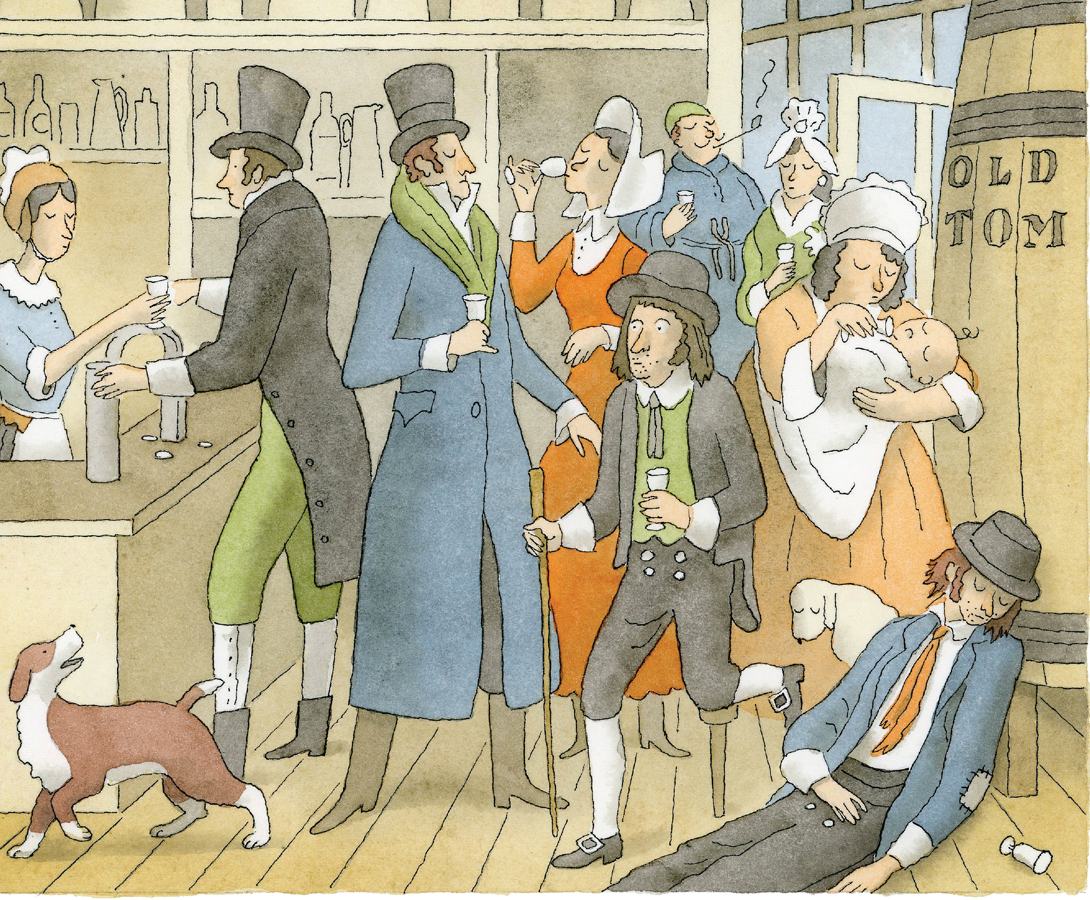

Gin, inexpensive to produce and safer to drink than London’s pathogen-laced water, became all the rage in Britain during the early eighteenth century, a period known as the Gin Craze. At one point there was one gin distillery for every four houses.

To curb consumption, a series of reforms were enacted, starting with the Gin Act of 1736, which led to rioting in the streets and resulted in reputable sellers going out of business. Bootleggers thrived, often selling gin of dubious quality—sometimes flavored with turpentine rather than juniper—with colorful names such as Ladies’ Delight and Cuckold’s Comfort.

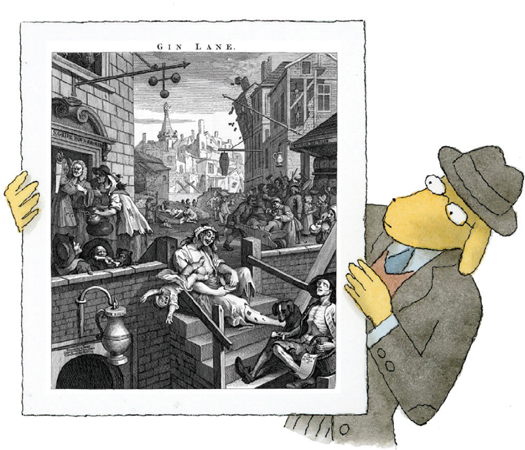

The popularity of gin among the poor contributed to its growing unsavory reputation. Dubbed “Mother’s ruin,” the spirit’s deleterious effect on the lower classes was famously depicted in William Hogarth’s satirical engraving Gin Lane (1751), sparking public outcry and further reform.

The emergence of the cocktail, or mixed drink, at the end of the eighteenth century in London helped to restore gin’s status over time, and by 1823, the hot gin twist—hot water and gin with sugar and lemon juice—was the city’s most popular drink.

Old Tom, the most popular gin style of the nineteenth century, was a bridge between the early sweet Dutch genever and later London dry styles.

Charles Dickens was a temperate drinker whose own cellar contained brandy, rum, whiskey, wine, and gin. His great-grandson, Cedric Dickens, writes in Drinking with Dickens (1998) that the famed author “loved the ritual of mixing the evening glass of Gin Punch, which he performed with all the energy and discrimination of Mr. Micawber”—a reference to the gin-punch-drinking character from David Copperfield (1850).

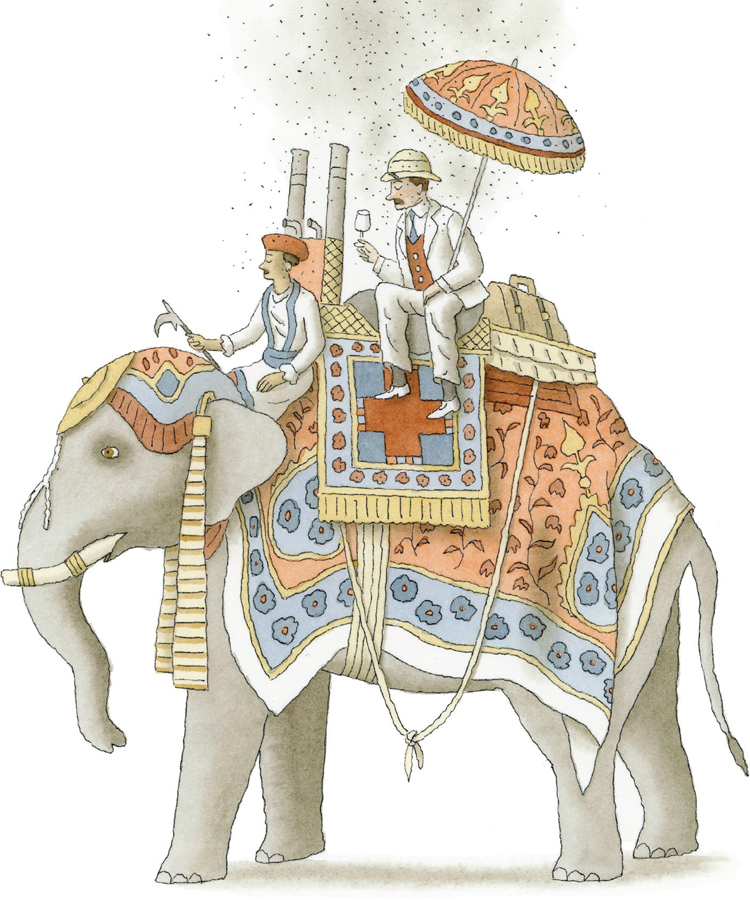

THE VENERABLE G & T

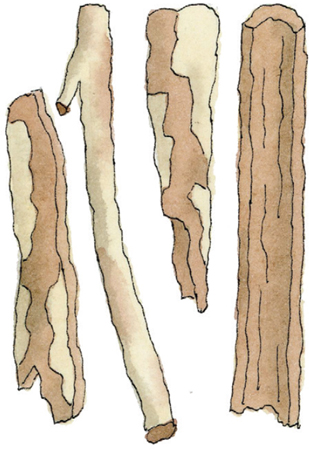

During the 1800s, the gin and tonic became the favorite drink of the army of the British East India Company. Troops stationed in India had been urged to ingest a daily dose of quinine, a powder ground from the bark of the cinchona tree, as a protective measure against malaria. Seeking to counter the bitterness of the quinine powder, officers began dissolving the substance in a mixture of sugar, carbonated water, and lime. It was only a matter of time before the concoction was combined with the typical soldier’s daily shots of gin, and the gin and tonic was born.

Strangely, the actual term “gin and tonic” doesn’t seem to turn up in fiction until P. G. Wodehouse’s Right Ho, Jeeves, in 1922.

Jeeves.

To this day, the gin and tonic remains a foundational piece of the gin cocktail canon. Contemporary British novelist Lawrence Osborne describes the classic drink in his trenchant travelogue on alcohol and Islam, The Wet and the Dry (2013): “The drink comes with a dim music of ice cubes and a perfume that touches the nose like a smell of warmed grass. Ease returns. It’s like cold steel in liquid form.”

Cinchona bark, the source of quinine.

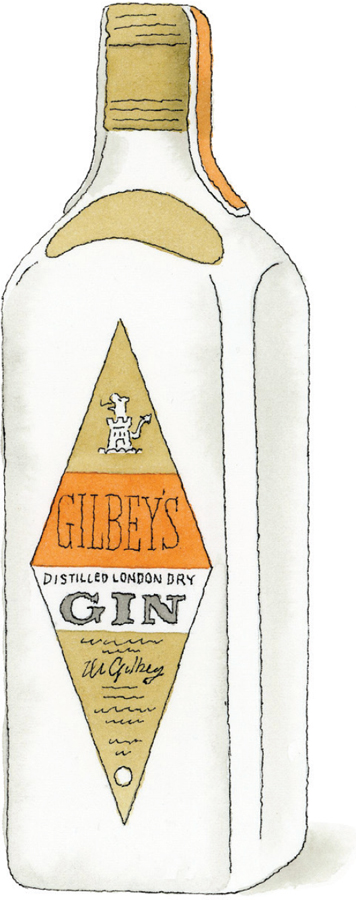

American writer John Cheever, “the Chekhov of the Suburbs,” was another heavy imbiber of the gin and tonic, referring to Gilbey’s gin as “mother’s milk.” He wrote a self-reflective short story that appeared in The New Yorker in 1953, entitled “The Sorrows of Gin,” about a little girl affected by the drinking and partying of her parents.

Cheever’s “mother milk.”

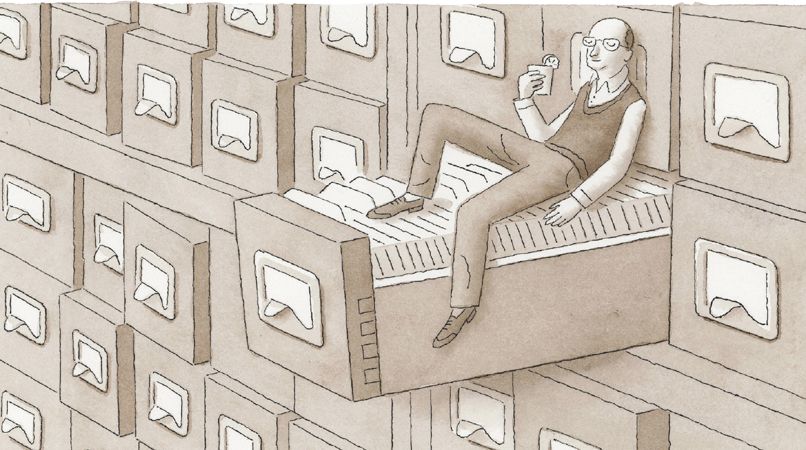

THE LUBRICATED LIBRARIAN

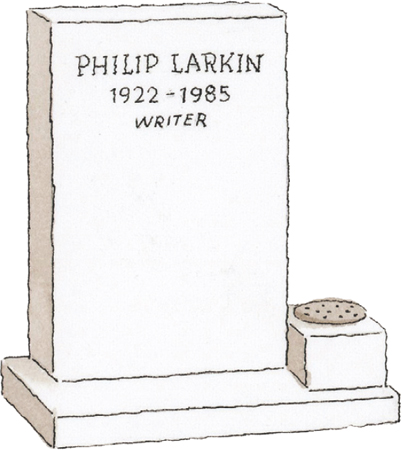

There may have been no more ardent G & T enthusiast among the literary set than Philip Larkin, the bespectacled British poet from Coventry, England. In 2001, Larkin’s longtime lover Monica Jones died, leaving behind some fourteen hundred letters from Larkin (who had died in 1985). The missives, compiled and edited by Anthony Thwaite under the title Letters to Monica, were published in 2010. Besides offering a glimpse into the mind of a famously inscrutable writer, they also confirm his affinity for gin and tonic.

Philip Larkin.

Larkin was the stereotypical fussy and repressed Englishman, whose quasi-reclusive lifestyle has been well documented. A self-styled wallower in misery, he once said, “Deprivation is for me what daffodils were for Wordsworth,” and he described himself as “an egg sculpted in lard, with goggles on.”

Larkin attended Oxford in the early 1940s. There he befriended Kingsley Amis, the two bonding over shared middle-class backgrounds, enthusiasm for jazz, distaste for English modernist writers, and a penchant for booze. They invented a game called “horsepissing” in which they amused themselves endlessly by replacing key words in famous works of literature with obscenities.

The friendship would later become frayed after the publication of Amis’s novel Lucky Jim in 1954. Although the book was dedicated to Larkin, it contained some transparent references to his relationship with Monica Jones that rankled the poet.

Kingsley Amis.

Larkin was notoriously ambivalent about his relationships with women, and he clung to the notion that his aversion to intimacy was a necessary condition for his art. He once wrote in his diary that “sex is too good to share with anyone else.” Nonetheless, at one point he managed to find himself juggling affairs with three different women, including Jones. In spite of his occasional dalliances over the years, she would stick with him.

Monica Jones.

Larkin first met Jones at University College of Leicester in 1946, when they were both twenty-four. He was an assistant librarian, and she was a lecturer in the English department. In addition to the two sharing intellectual pursuits, Jones matched Larkin’s enthusiasm for gin and tonics—at home she enjoyed them served in goblets the size of small fishbowls.

Larkin moved to Ireland in 1950 after being appointed sub-librarian at the Queen’s University of Belfast, marking the beginning of their written correspondence. They had become lovers by then, and their relationship would last more than forty years, until the poet’s death.

First edition, Faber & Faber, London, 2010.

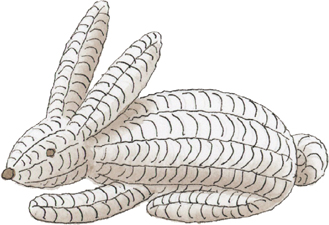

Larkin often addressed Monica as his “dearest bun” in his letters, a nod to Beatrix Potter’s bunnies, whom they both shared a fondness for. References to gin and drinking are also scattered throughout:

On Friday I “got drunk”—this is perhaps a theatrical way of saying I had two gins before supper instead of one.

I can feel my mind digging up years-old slights and getting furious over them. Only drink releases me from this bondage. I’m not the sort that gets angry when drunk.

God. Hay fever & drink. Still can’t quite taste gin, but am certainly feeling drunk. How did you think the poems looked? I like them drunk, prefer Posterity sober.

Larkin’s wicker rabbit, a gift from Monica.

He also expressed existential angst over the seeming pointlessness of his labors:

Morning, noon & bloody night,

Seven sodding days a week,

I slave at filthy work, that might

Be done by any book-drunk freak.

This goes on till I kick the bucket:

FUCK IT FUCK IT FUCK IT FUCK IT.

Later in life he would start drinking as soon as he returned home from his job running the Hull University library. He enjoyed solitary nights drinking and listening to his beloved jazz records. In a footnote to the second edition of All What Jazz (1985), a compilation of record reviews he wrote for the Daily Telegraph, he states: “Listening to new jazz records for an hour with a pint of gin and tonic is the best remedy for a day’s work I know.”

Larkin’s jazz favorites were prebop icons like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Sidney Bechet.

In his poem “Sympathy in White Major” (1974) he actually sets down in verse the instructions for making a perfect gin and tonic:

When I drop four cubes of ice

Chimingly in a glass, and add

Three goes of gin, a lemon slice,

And let a ten-ounce tonic void

In foaming gulps until it smothers

Everything else up to the edge . . .

Larkin always feared that he would die at sixty-three like his father—and he did. Delivering the eulogy, Kingsley Amis summed him up as a private man “who found the universe a bleak and hostile place and recognized clearly the disagreeable realities of human life, above all the dreadful effects of time on all we have and are.”

THE LIQUID FUEL OF THE ROARING TWENTIES

Prohibition in the United States (1920–1933) sent gin production underground. The spirit’s ease of production—unlike whiskey, it was ready to drink right away—made it popular with bootleggers. It became the most common liquor offered at the illicit drinking establishments known as speakeasies.

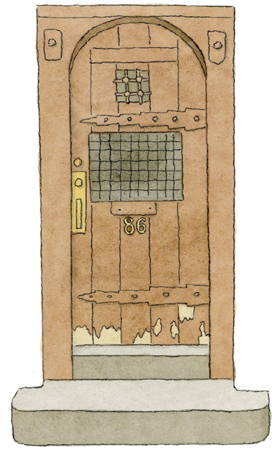

The unmarked door of Chumley’s, an original New York City speakeasy at 86 Bedford Street. Established in 1922 and still open today, it catered to a literary set that included F. Scott Fitzgerald, Willa Cather, William Faulkner, Ring Lardner, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, and later the Beat Generation.

Heightened demand for the spirit spawned the creation of “bathtub gin,” produced in private homes for consumption in hidden back rooms as well as speakeasies. Gin required water, and the large jugs used to steep the ingredients were too big to fit under a sink tap, so a bathtub tap was used.

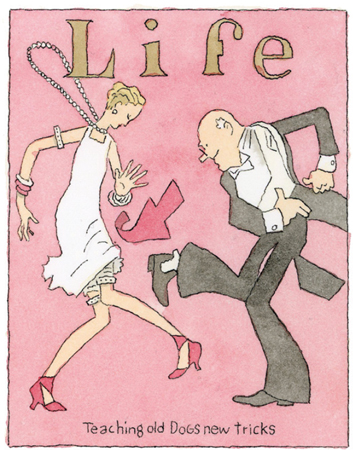

Life magazine cover art by John Held Jr., February 18, 1926.

Unscrupulous producers turned to widely available, and toxic, industrial alcohols like methanol (used in fuels, polishes, and lubricants) as a substitute for ethanol (the grain alcohol and basic intoxicating agent in all spirits). This contributed to bathtub gin’s dubious reputation—ten thousand people died from drinking bad gin and other poisonous spirits during Prohibition.

In the 1910s and ’20s the Bronx cocktail was a popular drink made with gin, sweet and dry vermouth, and orange juice. It was the kissing cousin of the equally popular rye-whiskey-based Manhattan cocktail. According to sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, and author W. E. B. Du Bois, knowing the difference between the two drinks signaled one’s drinkerly erudition and socioeconomic status. In his 1940 autobiographical work Dusk of Dawn, Du Bois describes a Brooks Brothers– clad white minister who “plays keen golf, smokes a rare weed and knows a Bronx cocktail from a Manhattan.”

THE ORIGINAL GREENWICH VILLAGE BOHEMIAN

Gin-loving American poet Maxwell Bodenheim may have been the spirit’s first Jazz Age casualty. He arrived in New York in 1915, quickly achieving a measure of critical success and appearing in poetry journals alongside Ezra Pound and Edgar Lee Masters. He was soon garnering a reputation as a dissolute and lecherous ladies’ man. His friend Ben Hecht wrote that Max was “kicked down more flights of stairs than any poet of whom I have heard or read.”

Maxwell Bodenheim.

His early success was followed by a period of rapid decline. By the end of his life, he was spending hours in his favorite booth at the San Remo Café on MacDougal Street, peddling his poems in exchange for money to buy gin.

His final, posthumously published book, My Life and Loves in Greenwich Village (1954), was a ghostwritten volume cobbled together from his drunken ramblings.

Paperback edition published by Belmont, 1961.

THE SHIT-FACED PRODIGY OF THE JAZZ AGE

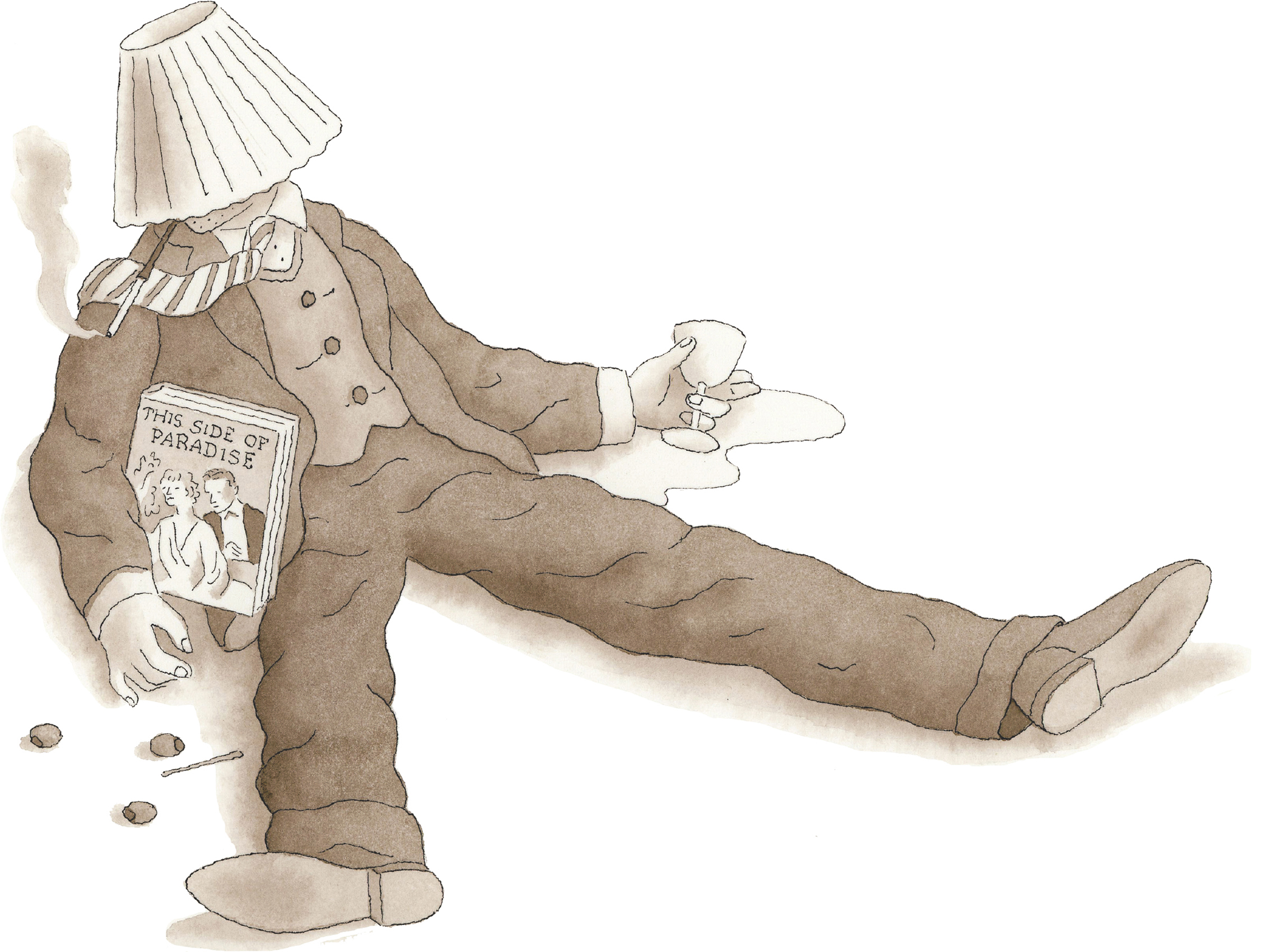

F. Scott Fitzgerald did his part to help glamorize gin. The celebrated American writer, along with his flapper wife, Zelda, encapsulated and chronicled the spirit and excesses of the era. His premature death at age forty-four was the culmination of years of hard drinking.

At the time of his graduation from Princeton in 1916, his immoderate drinking patterns were already well established. Following the 1920 publication of his wildly successful debut novel, This Side of Paradise, Fitzgerald soon acquired a reputation as a boorish cocktail-party drunk, known for hurling ashtrays and insults.

F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Ernest Hemingway would later refer to him as a lightweight in A Moveable Feast, writing that “it was hard to accept him as a drunkard, since he was affected by such small quantities of alcohol.”

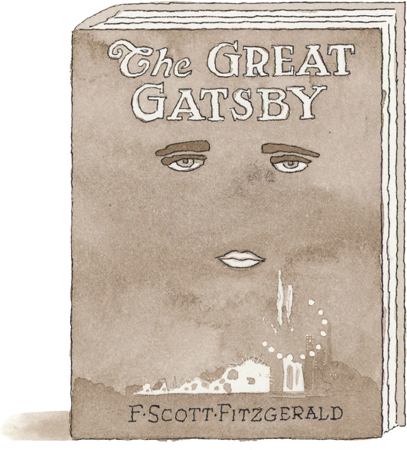

The gin rickey—gin, ice, club soda, and half a squeezed lime—was the most popular gin drink of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and a favorite of Fitzgerald’s. In a scene from The Great Gatsby (1925), the cocktail makes an appearance in a hotel room on a stiflingly hot day:

Tom came back, preceding four gin rickeys that clicked full of ice.

Gatsby took up his drink.

“They certainly look cool,” he said, with visible tension.

We drank in long, greedy swallows.

First edition published by Scribner’s, 1925. Fitzgerald, inspired by the lavish parties he attended on Long Island, began planning the novel in 1923.

Upon its initial publication in 1925, Gatsby was considered a flop, receiving mixed reviews and selling just over twenty thousand copies. Although it was never popular in Fitzgerald’s lifetime, today it is among the most beloved of American novels and continues to sell more than five hundred thousand copies a year.

Zelda Fitzgerald.

However, many of Fitzgerald’s contemporaries saw it for the masterpiece that it was. In a letter to Fitzgerald, T. S. Eliot wrote, “It seems to me to be the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James.”

Fitzgerald, whose preferred gin was said to be Gordon’s, credited alcohol with fueling his creative process. He wrote: “Drink heightens feeling. When I drink, it heightens my emotions and I put it in a story. . . . My stories when written sober are stupid.”

But the cumulative effect of years of intemperance eventually took a toll. Between 1933 and 1937, Scott was hospitalized for alcoholism eight times.

Early twentieth-century Gordon’s gin label.

Following a series of career setbacks, Fitzgerald moved to Los Angeles in 1937 to work as a screenwriter for the film studio MGM. By this time, he needed to earn money to support Zelda, who was in a sanitarium, and his daughter, Scottie, a student at Vassar. Fitzgerald’s secretary and assistant in LA, Frances Kroll Ring, wrote in her memoir of stuffing empty gin bottles into burlap potato sacks and disposing of them in a brushy ravine.

Fitzgerald died of a heart attack on December 21, 1940, at his mistress’s Hollywood apartment. His unfinished novel, The Last Tycoon, was published posthumously in 1941.

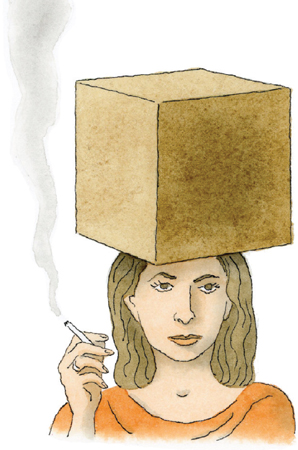

THE VERSATILE MIXER

Unlike whiskey or tequila, gin is seldom drunk neat. Most literary enthusiasts of the spirit preferred it in the form of one of its iconic cocktail iterations, such as Larkin’s aforementioned gin and tonic, or, in the case of Joan Didion, adulterated with hot water. The author described her remedy for writer’s block in the preface to Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968): “I drank gin-and-hot-water to blunt the pain and took Dexedrine to blunt the gin.”

Joan Didion.

Raymond Chandler had a thing for the gimlet. His preferred preparation for the cocktail is described in The Long Goodbye (1953), as detective Philip Marlowe recounts a bar conversation with character Terry Lennox:

We sat in a corner of the bar at Victor’s and drank gimlets. “They don’t know how to make them here,” he said. “What they call a gimlet is just some lime or lemon juice and gin with a dash of sugar and bitters. A real gimlet is half gin and half Rose’s Lime Juice and nothing else. It beats martinis hollow.”

THE RAMOS GIN FIZZ

The Ramos gin fizz was a favorite of southern playwright Tennessee Williams, the author of A Streetcar Named Desire (1947). The original recipe, created in New Orleans in 1888 by bartender Henry Ramos, calls for shaking the strainer for a full twelve minutes to create a proper foam.

Ramos Gin Fizz

1½ ounces London dry gin

1 medium egg white

¾ ounce simple syrup

½ ounce freshly squeezed lime juice

½ ounce half-and-half

3 dashes orange blossom water (also called orange flower water)

2 ounces club soda

Orange wedge

In a cocktail shaker, combine the gin, egg white, simple syrup, lime juice, half-and-half, and orange blossom water. Shake vigorously for at least 1 minute. Strain into a Collins glass with no ice, then add the club soda. The drink will be foamy. Top with any excess foam from the cocktail shaker. Garnish with an orange wedge and serve immediately with a straw.

Alvin Lustig’s 1947 book cover design.

THE MARTINI LOOMS LARGE

The relative ease of illegal gin production during Prohibition helped popularize the traditional gin martini (and a real martini means gin, not vodka), which would go on to become America’s predominant cocktail of the mid-twentieth century.

The martini had no shortage of notable enthusiasts . . .

H. L. Mencken, the American journalist and critic, waxed poetic when calling the martini “the only American invention as perfect as a sonnet.”

Probably the most famous utterance in martini lore is attributed, perhaps spuriously, to the Algonquin Round Table stalwart Dorothy Parker:

I like to have a martini,

Two at the very most.

After three I’m under the table,

After four I’m under my host.

Dorothy Parker.

At Harry’s Bar in Venice, Ernest Hemingway drank his own dry variant of the martini using a 15:1 gin-to-vermouth ratio. He dubbed it the Montgomery (after British field marshal Bernard Montgomery, who preferred going into battle with a 15:1 troop advantage).

Ernest Hemingway.

The martini was “the elixir of quietude,” according to E. B. White, who once mentioned in a letter to a friend that a single dry martini could effectively dislodge his occasional writer’s block.

E. B. White.

Patricia Highsmith, author of The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) and no stranger to the martini, began drinking as a student at Barnard College. In an early 1940s diary entry, she wrote about the vital role that booze plays for an artist because it allows one to “see the truth, the simplicity, and the primitive emotions once more.”

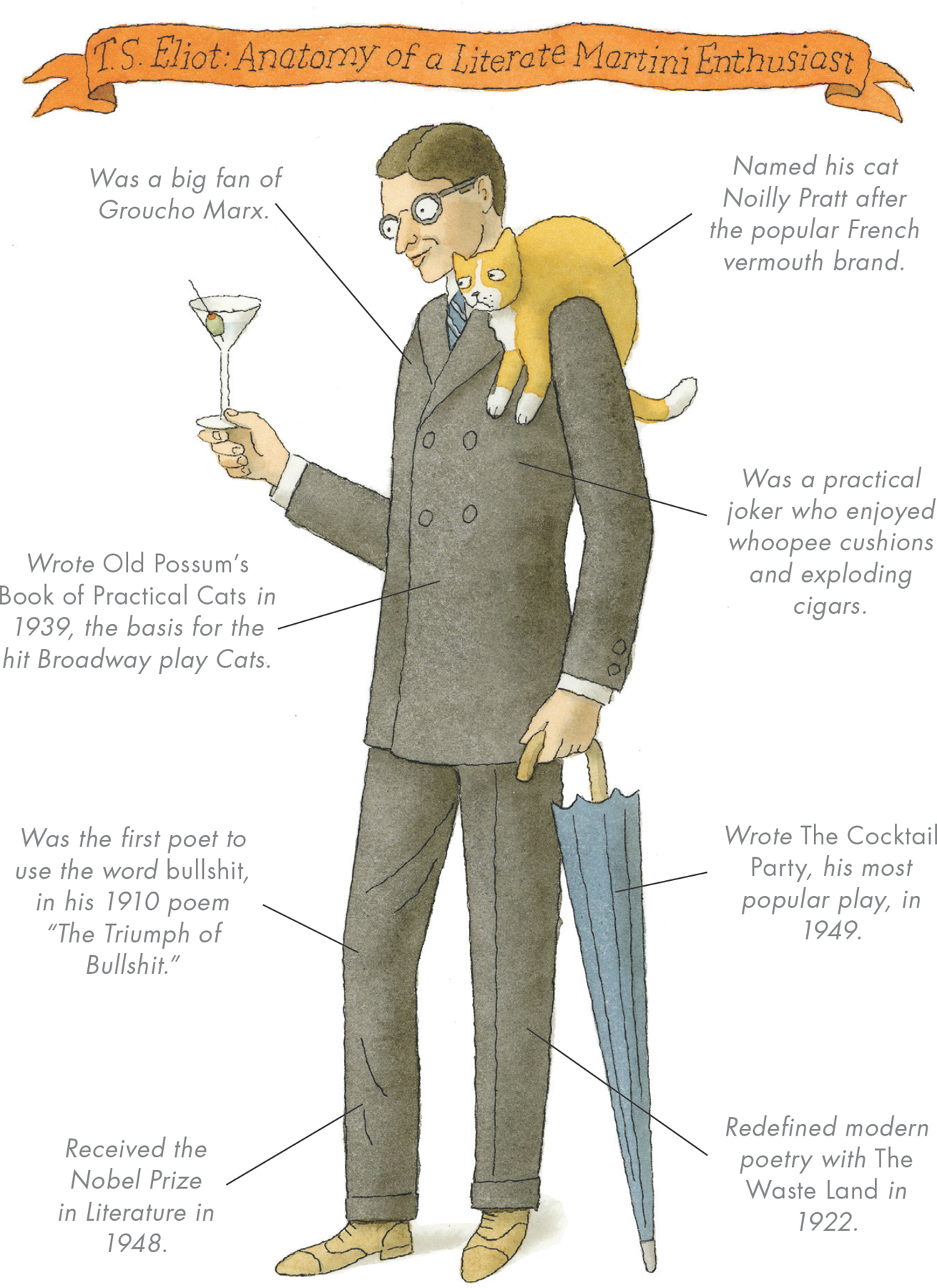

When asked by an admirer about the source of his inspiration, T. S. Eliot replied, “Gin and drugs, dear lady, gin and drugs.” He would also proclaim, “There is nothing quite so stimulating as a dry martini cocktail.”

In The Letters of T. S. Eliot, he describes how he wrote the monologue to the verse drama Sweeney Agonistes: “I wrote it in three quarters of an hour after church time and before lunch one Sunday morning, with the assistance of half a bottle of Booth’s gin.”

THE CLASSIC DRY GIN MARTINI

As with most legacy cocktails, the martini’s origins are disputed. Some drink historians believe that the cocktail’s name comes from the Italian vermouth brand Martini & Rossi, which was first marketed in 1863. Others contend that it evolved from a cocktail called the Martinez, which was served at the Occidental Hotel in San Francisco in the early 1860s and named for a nearby town. Another theory traces the martini back to the Knickerbocker Hotel in New York City around 1912.

The “proper” ratio of gin to vermouth in a martini has changed over time as taste preferences have moved to the dryer end of the spectrum (less vermouth). In the 1930s the ratio was 3:1, in the 1940s it was 4:1. By the late twentieth century, it was not uncommon for a bartender to spray just a mist of vermouth into the glass with an atomizer.

Noël Coward, preferring his martinis extremely dry, once declared, “A perfect martini should be made by filling a glass with gin, then waving it in the general direction of Italy (the producer of vermouth).”

Gin Martini

Cracked ice

2½ ounces London dry gin (such as Bombay, Beefeater, or Gordon’s)

½ ounce dry vermouth, preferably Noilly Prat

Green olive for garnish

Fill a cocktail shaker or mixing glass with ice. Add the gin and vermouth. Stir well, about 20 seconds, then strain into a martini glass. Garnish with the olive.

The most iconic glass shape in cocktail history.

BOTANICAL MANIA

Gin, like all traditional spirits, has benefited immensely from the modern craft-cocktail movement. At its core gin is juniper-infused vodka, but after that the botanical variations of gin are endless. Bombay Sapphire kicked things off in 1987, creating the first commercial gin to depart from the classic juniper-forward “London dry” style with a recipe of ten ingredients including almond, lemon peel, orrisroot, and grain of paradise.

Since then innovative microdistillers have run wild, incorporating unusual new botanicals such as white pine, Oregon grape, cumin, lavender, saffron, marionberries, coconut, and seaweed. Faced with sampling the sheer number of disparate gin offerings available today, writers of yesteryear would have been hard-pressed to find time in front of the typewriter.