Vodka goes well with a wintery perspective. Nothing else provokes such presentiments of falling snow, except for some, the communist seizure of the state.

—Michèle Bernstein, All the King’s Horses (1960)

In Eastern Europe, vodka has been the dominant spirit for centuries. However, its popularity in the West, and particularly the United States, is a relatively recent phenomenon. It didn’t gain traction here until the latter half of the twentieth century. Consequently, vodka missed America’s Prohibition era, and the beginnings of the great writer/booze confluence of the 1920s. As a result, the literary icons of the Jazz Age were largely unaware of the spirit, and little was drunk or written about it. The Russians, of course, have been writing about vodka for eons. Although late to the party, vodka would eventually get its moment in the sun, ultimately going on to surpass whiskey and gin as the world’s top-selling spirit.

THE NATIONAL DRINK OF RUSSIA AND POLAND

As with all spirits, vodka’s early history is muddled and the subject of much speculation. With scant historical evidence to support competing claims, just about the only thing that scholars can agree on is that vodka originated either in Poland or in Russia. The spirit plays a seminal role in the drinking history of both countries, but Russia is where it has long been deeply embedded in the national psyche.

BURNT WATER

The name vodka is generally acknowledged as a derivative of voda, the Slavic word for “little water” (or the Polish woda). The first mention of vodka may have appeared in Polish court documents from 1405, but the present usage as a term for a clear ethanol-based spirit didn’t achieve wide usage in the Russian language until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Potatoes, eventually a key vodka ingredient, didn’t arrive in Europe until the sixteenth century.

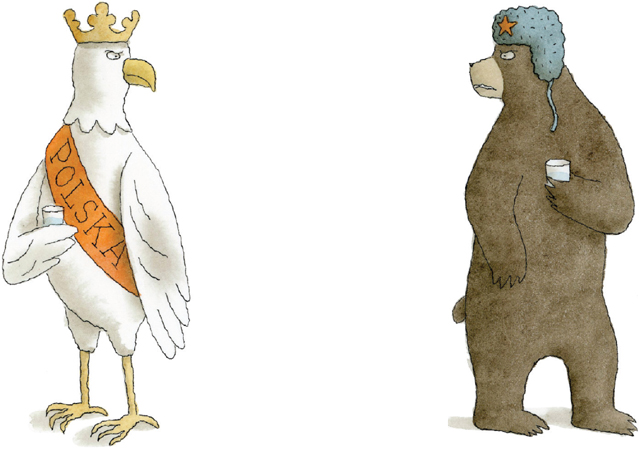

Early prototypes of the colorless spirit were distilled from a fermented mash of grain, corn, or grape must, and were produced under a variety of different names including bread wine, distilled wine, vinum crematum (Latin for “burnt wine”), and aqua vitae (Latin for “water of life”). Potatoes, eventually a key vodka ingredient, didn’t arrive in Europe until the sixteenth century.

POLISH TINCTURE

Poland lays claim to having produced an early prototype of vodka in the eighth century, but this may have been a distillation of wine—more akin to a crude brandy. The first documented evidence of grain-based wines in Russia occurred as early as the ninth century.

Applying bellows to the furnace during distillation, fifteenth century.

Later iterations of Polish vodka appeared in the eleventh century under the name gorzalka (“burnt water”—a reference to alcohol produced during the heating process in a still). Gorzalka and other vodka antecedents, like most distilled liquors produced then and throughout the Middle Ages, were intended primarily as pharmaceutical tinctures. These early, primitive grain distillates were harsh and cloudy, bearing little resemblance to modern vodka.

One of the earliest mentions of vodka in Polish literature occurs in national poet Adam Mickiewicz’s epic poem Pan Tadeusz (1834). The poem is a paean to Old Polish culinary traditions. A sample couplet:

The men were given vodka; and all took their seat,

And Lithuanian cold barszcz [borscht] all proceeded to eat.

VODKA’S EARLY MOSCOW YEARS

Ground zero for something akin to modern Russian vodka is hotly debated. According to one theory, the science of distillation was introduced in Moscow in 1386 when ambassadors from Kaffa, a Genoese colony in the Crimea, presented aqua vitae, an aqueous solution of ethanol distilled from grape must, to Grand Prince Dmitry Donskoy.

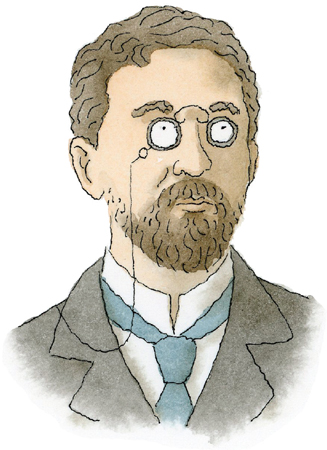

Grand Prince Dmitry Donskoy.

Another Russian legend maintains that a Russian Orthodox monk named Isidore, from the Chudov Monastery inside the Kremlin in Moscow, concocted the first high-quality recipe for Russian grain vodka around 1430, and dubbed it “bread wine.” No historical documentation exists to support this claim.

Grand Prince Ivan III, seeing an enormous revenue opportunity, established state control over vodka production and distribution between 1472 and 1478. This would be the first of many government monopolies on vodka established and repealed over the course of Russian history.

THE BIG EAGLE

In Russia a man’s drinking prowess was a measure of his virility. Teetotalers were eyed with suspicion. The eighteenth-century tsar Peter the Great, whose favorite drink was anise-flavored vodka, prided himself on his ability to drink prodigiously without getting drunk and was purportedly impervious to hangovers. As a punishment for guests who arrived late to official court feasts, hoping to avoid excessive drinking, he established what was known as the “penalty shot”—in the form of a 1.5-liter goblet named “the Big Eagle.”

In 1863 the state monopoly on vodka was repealed, triggering a drop in prices and making the spirit accessible to all classes. It soon became the drink of choice for most Russians. In the nineteenth century, Russian soldiers fighting in the Napoleonic Wars helped spread vodka across Europe.

THE RUSSIAN SHAKESPEARE

Aleksandr Pushkin, often dubbed “the Russian Shakespeare,” was the first of the country’s great writers to mention vodka in his work. The spirit’s role in Russian life is alluded to in his short story “The Shot” (1830): “The best marksman I ever met used to shoot every day, at least three times before dinner. It was as much a part of his daily routine as a glass of vodka.”

It was not uncommon in Russia for children to drink vodka, and not only during social and ceremonial functions. Early introduction to alcohol was believed to prevent alcoholism. In an 1834 letter to his wife regarding their young son, Pushkin wrote: “I’m happy to hear that Sashka has been weaned . . . the fact that the wet nurse was in the habit of drinking before bed is no great misfortune. The boy will grow accustomed to vodka.”

DOSTOYEVSKY AND THE LIQUID MENACE

In a marked departure from the West, Russian literature is relatively lacking in the glorification of drink. Many Russian writers have tended to take a dim view of the subject, in light of Russia’s long and often woeful history of inebriation.

Alcohol’s pernicious effect on the Russian soul was a common theme in the work of Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The original working title for Crime and Punishment (1866) was The Drunkards. In a letter to his editor, Andrei Krayevsky, Dostoyevsky wrote, “[The novel] will be connected with the current problem of drunkenness. Not only is the problem examined, but all of its ramifications are represented, most of all depictions of families, the bringing up of children under these circumstances, and so on.”

Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

In his novel Demons (1871), Dostoyevsky declares, “The Russian God has already been vanquished by cheap vodka. The peasants are drunk, the mothers are drunk, the children are drunk, the churches are empty.”

Not that Dostoyevsky was above enjoying the spirit himself. Mikhail Alexandrov, a friend and writing colleague, recorded the writer’s morning ritual in his diary: “Once when I visited Fyodor Mikhailovich during breakfast, I saw how he consumed simple grain vodka; he bit off some brown bread, took a sip from a glass of vodka, and then chewed it all together.”

Russians traditionally enjoy their vodka with food. One of its classic pairings is caviar.

LEO THE KILLJOY

In a closed society subject to censorship, where vodka, politics, and money have been inextricably bound for centuries, many writers have been reticent to express themselves freely on the subject of drinking. Leo Tolstoy, emboldened by his international celebrity, was not one of them.

The author of War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1873) regarded vodka not only as a poison but as a profitable instrument of suppression of the peasantry by the autocracy. In 1887 he founded a temperance society called the Union Against Drunkenness, and in 1890 he penned a famous essay titled “Why Do Men Stupefy Themselves?” In it he wrote: “The cause of the world-wide consumption of hashish, opium, wine, and tobacco, lies not in the taste, nor in any pleasure, recreation, or mirth they afford, but simply in man’s need to hide from himself the demands of conscience.”

Leo Tolstoy.

THE VODKA AGNOSTIC

Anton Chekov’s views on vodka, and alcohol in general, wavered between disdain and sympathy. The great Russian short-fiction writer decried vodka producers as “Satan’s blood peddlers”—two of his brothers were alcoholics—but he also understood the human desire for a salve against the harsh realities of daily existence. The heavy drinkers in his stories and plays are rendered with humor and compassion.

Anton Chekhov sporting his signature pince-nez.

After being admonished by his niece for drinking with his doctor, the title character of Chekhov’s play Uncle Vanya (1896) remarks, “When real life is missing, one must create an illusion.”

In Chekov’s short story “At Sea: A Sailor’s Story” (1883) one of the dissolute protagonists exclaims: “We sailors drink a lot of vodka and sin left and right because we do not know what good virtue does anyone at sea.”

THE RUSSIAN BUKOWSKI

And then there was Venedikt Erofeev, the unapologetic vodka enthusiast, known as much for his fondness for the spirit as for his writing. His early Brezhnev-era comic masterpiece, Moscow to the End of the Line (1969), depicts one of world literature’s most famous alcoholic benders. The pseudo-autobiographical prose poem recounts a vodka-soaked train journey from Moscow to Petushki taken by a recently fired cable fitter to visit his lover and young son. During the phantasmagoric trip, the narrator, Venichka, engages in philosophical discussions about drinking with fellow travelers, oversleeps and misses his station, and eventually wakes up on a train headed back to Moscow.

Venedikt Erofeev’s forward-swept hair predates Justin Bieber.

Alexander Genis, a Russian American author, describes Erofeev as “a great explorer of the metaphysics of drink. For him, alcohol is a concentrated otherworldliness. Intoxication is a means of breaking free, of becoming—literally—not of this world. Vodka is the midwife of the new reality.”

Large quantities of Stolichnaya are consumed in Moscow to the End of the Line.

TWENTIETH-CENTURY RUSSIAN HEADS OF STATE AND VODKA

Vladimir Mayakovsky, the leading poet of the Russian Revolution of 1917, famously said it was “better to die of vodka than of boredom.” Russian leaders were not united in their feelings on the subject . . .

In 1914, Tsar Nicholas II, convinced that his inebriated soldiers had cost him the Russo-Japanese War, issued a decree banning the production and sale of alcohol.

Vladimir Lenin declared that “vodka and other narcotics will draw us back to capitalism, rather than forward to Communism,” and ordered drunkards to be shot.

Joseph Stalin used vodka sales to finance the socialist industrialization of the Soviet Union.

Nikita Khrushchev’s favorite drink was pepper vodka.

Leonid Brezhnev preferred Zubrówka, a bison-grass-flavored vodka from Belarus.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s first official act as general secretary in 1985 was to launch a temperance campaign restricting access to vodka, making him hugely unpopular.

His successor, the hard-drinking Boris Yeltsin, became known for his vodka-fueled antics on the world stage.

Today Vladimir Putin is not big on hard liquor and reportedly prefers beer to vodka.

VODKA IN AMERICA

Despite the ubiquity of vodka in the United States today—one out of three cocktails ordered in the United States contains the spirit—its early stateside years were rocky. Emerging from Prohibition, Americans already had a favorite colorless spirit—gin. As a relatively flavorless competitor, vodka was a hard sell.

Following the end of Prohibition in 1933, Vladimir Smirnov, the son of the hugely successful Russian distillery founder Pyotr Smirnov, sold the name, recipe, and production rights in the United States to Rudolph Kunett, a Ukranian American. Kunett set up shop in Bethel, Connecticut, but was unprepared for America’s indifference to the liquor. After five fruitless years, he sold the business to John G. Martin, the president of Heublein Inc. for fourteen thousand dollars.

John G. Martin, the man who made vodka popular in the United States.

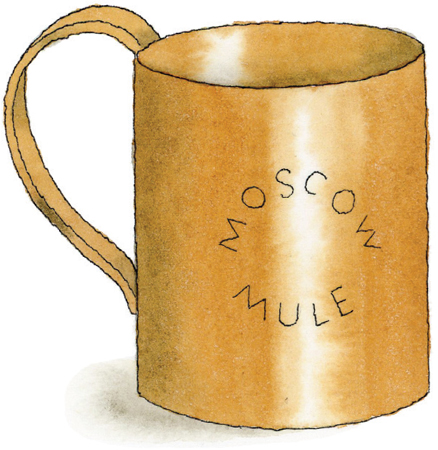

Sales remained flat for several years, but in 1941, Martin traveled to Los Angeles and met Jack Morgan, owner of the Hollywood restaurant the Cock’n Bull. Morgan had a surplus of British ginger beer he’d been unable to sell. With two products on their hands that nobody wanted, they tried mixing vodka with ginger beer, and the result was the Moscow mule. The cocktail’s instant success was the American foothold the spirit needed. Bartenders suddenly saw its enormous potential as a neutral mixing agent.

One of Martin’s marketing gimmicks was to serve the Moscow mule in a copper mug.

THE VODKA TONIC

Unlike their Eastern European counterparts who drink vodka neat, most Western devotees have preferred the spirit diluted with another beverage, or as the active ingredient in a cocktail.

American writer and Beat Generation icon William S. Burroughs, who once said, “Our national drug is alcohol,” was often spotted in later years consuming his signature vodka and Coke.

The most enduring vodka mixer has been tonic water. Christopher Isherwood, the English American novelist, worried about drinking too many of them. The author, whose Berlin Stories (1945) is set in the boozy, libertine years leading up to the rise of Hitler, was acutely mindful of the potential long-term damage to his health. In his posthumously published diaries (1996) he often begins his entries with “Today I’m going to stop smoking and drinking vodka tonics.”

Christopher Isherwood.

Another fan of the vodka tonic was Pete Hamill, the hard-drinking NYC journalist who was a regular at the Greenwich Village tavern the Lion’s Head. At the legendary literary bar Hamill traded stories with the likes of Frank McCourt, Seamus Heaney, and Norman Mailer. In his memoir A Drinking Life (1995), Hamill writes: “I don’t think many New York bars ever had such a glorious mixture of newspapermen, painters, musicians, seamen, ex-communists, priests and nuns, athletes, stockbrokers, politicians, and folksingers, bound together in the leveling democracy of drink.” But at thirty-eight, Hamill acknowledged the toll on his body and mind and hung up his shot glass for good. His last drink in 1972 was a vodka tonic.

Several blocks away from the Lion’s Head (shuttered in 1996) in Greenwich Village was the legendary White Horse Tavern, a literary stomping ground in the 1950s and ‘60s for such notables as Jack Kerouac, Anaïs Nin, James Baldwin, Norman Mailer, and Hunter S. Thompson.

SHAKEN NOT STIRRED

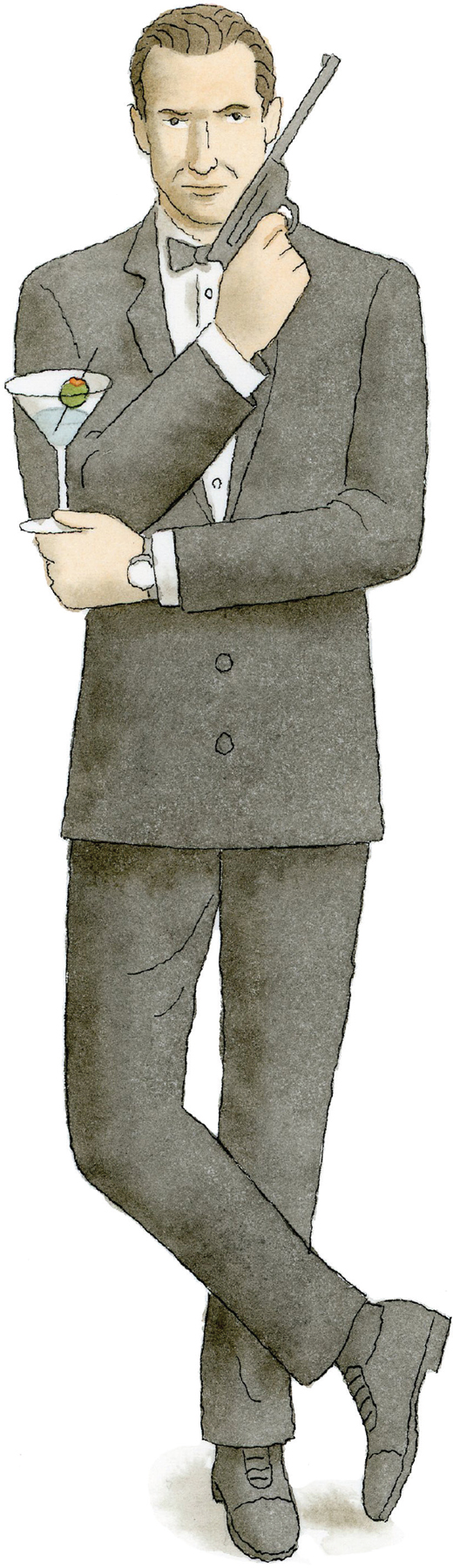

Novelist Ian Fleming would inadvertently boost vodka sales in the 1960s when his fictional British Secret Service agent James Bond transitioned to the silver screen. In the films Bond’s signature drink was the vodka martini, shaken not stirred. Prior to Bond, ordering a martini meant a gin martini. Shaking, so the theory went, would “bruise” the gin—but apparently vodka wasn’t so delicate.

However, the Bond of Fleming’s books wasn’t quite so adamant about vodka—he often ordered gin martinis as well. In the first title of the series, Casino Royale (1953), Bond orders a vesper, containing both vodka and gin, with precise instructions to the bartender: “Three measures of Gordon’s [gin], one of vodka, half a measure of Kina Lillet. Shake it very well until it’s ice-cold, then add a large thin slice of lemon peel. Got it?”

Ian Fleming’s James Bond.

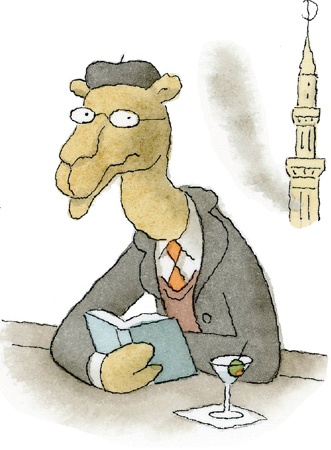

Contemporary novelist and fellow Brit Lawrence Osborne also enjoys a well-made vodka martini. In The Wet and the Dry (2013) he revels in the danger associated with drinking in the largely dry countries of the Middle East. Sitting in Le Bristol Hotel in Beirut, with an armed soldier stationed outside the revolving glass doors, he describes the inconspicuous bar as “an exercise in discretion,” before slipping into his vodka martini: “Salty like cold seawater at the bottom of an oyster, the drink strikes you as sinister and cool and satisfying to the nerves, because it takes a certain nerve to drink it.”

SCREWDRIVER

The screwdriver—orange juice and vodka—was Truman Capote’s tipple of choice. The author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958) and In Cold Blood (1966) referred to it as “my orange drink.”

According to Victorino Matus, author of Vodka: How a Colorless, Odorless, Flavorless Spirit Conquered America (2014), the cocktail got its name from American oil rig workers in the Persian Gulf in the late 1940s. While on the job, they discreetly added vodka to their orange juice and stirred with the closest implement on hand—a screwdriver.

Screwdriver

Ice

2 ounces vodka

Orange juice

Orange wedge for garnish

In a highball glass with ice, pour in the vodka and fill with orange juice. Garnish with the orange wedge.

WHERE I’M DRINKING FROM

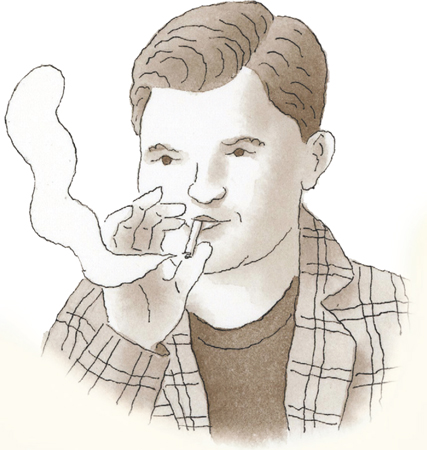

Raymond Carver was called the “the Chekhov of Middle America” by the Times of London. Carver, whose spare prose did much to reinvigorate the American short story in the 1980s, was also, for most of his adult life, hopelessly in the thrall of vodka. But unlike so many of his alcoholic forebears, he was eventually able to walk away from it.

Carver grew up in the small town of Yakima, in eastern Washington, where his father worked in a sawmill. Both of his parents drank, and he got his first taste of alcohol as a child. In a 1983 interview with the Paris Review, he recounted the experience:

“In the cabinet under the kitchen sink, [my mother] kept a bottle of patent ‘nerve medicine,’ and she’d take a couple of tablespoons of this every morning. My dad’s nerve medicine was whiskey. . . . I remember sneaking a taste of it once and hating it, and wondering how anybody could drink the stuff.”

Carver started smoking in his early teens to help combat a weight problem. His parents often bought him his own carton so he wouldn’t mooch from theirs.

His first published story was called “Pastoral,” which appeared in the Western Humanities Review in 1963. He was thrilled that Charles Bukowski had a poem in the same issue.

While teaching in Iowa in 1973 with fellow Chekhovian inebriate John Cheever, Carver later wrote that “he and I did nothing but drink. . . . We met our classes in a manner of speaking, but the entire time we were there . . . I don’t think either of us ever took the covers off our typewriters.”

John Cheever, “the Chekhov of the Suburbs.”

According to his biographer, Carol Sklenicka, Carver drank vodka at his dining room table while correcting the printer’s galleys for his first book of short stories, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? (1976).

First edition, 1976, published by McGraw-Hill, New York.

Carver’s drinking wrecked his first marriage, to Maryann Burk Carver. In her 2006 memoir, What It Used to Be Like: A Portrait of My Marriage to Raymond Carver, Maryann recounts a drunken episode where he cracked her over the head with his vodka bottle, nearly killing her.

In 1977, after two visits to a recovery center and three to a hospital, Carver gave up drinking. His friend Douglas Unger, the American novelist, has said, “Ray confessed several times that he wasn’t sure if, in sobriety, he would ever be able to write again.”

In fact, his final eleven years sober turned out to be his most productive, culminating in the publication of his landmark collection Cathedral (1984). Included in the collection was the award-winning story “Where I’m Calling From,” which focuses on an alcoholic at a “drying-out facility.” J.P., the narrator, invokes Jack London’s story “To Build a Fire” as a metaphor for recovery—he can either freeze to death or choose life by building a fire.

First edition, 1983, published by Alfred E. Knopf, New York.

Reflecting back on his drinking in the Paris Review interview, Carver said: “Of course there’s a mythology that goes along with the drinking, but I was never into that. I was into the drinking itself. I suppose I began to drink heavily after I’d realized that the things I wanted most in life for myself and my writing, and my wife and my children, were simply not going to happen.”

In his essay “Raymond Carver and the Ethos of Drinking,” David McCracken remarks that in many of Carver’s stories his characters paradoxically rely on alcohol to treat the very problems caused by their alcohol dependence. He writes: “In Carver’s fictional universe, drinking gives many characters a sense of stability through which they can evaluate their lives, even if this stability is fleeting.”

Carver, also a heavy cigarette smoker, died in 1988 of lung cancer.

Carver referred to the version of himself during his drinking days as “Bad Raymond.”

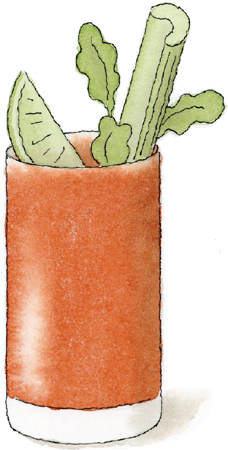

THE BLOODY MARY

Industrious writers who drink heavily inevitably must contend with the biggest obstacle to resuming work the next day: the hangover. Ernest Hemingway and Raymond Carver preferred the “hair of the dog” approach, usually in the form of a bloody mary.

The popular creation story for the drink is that, in the 1920s, bartender Fernand “Pete” Petiot first mixed vodka and tomato juice at Harry’s New York Bar in Paris.

In 1934, after Prohibition, Petiot helmed the King Cole Bar at New York’s St. Regis Hotel, where he introduced a similar drink consisting of vodka, tomato juice, citrus, and spices. The hotel’s owner, Vincent Astor, objected to the name bloody mary, so the drink was initially dubbed the red snapper.

A comedian named George Jessel also claimed to have created the drink, at the Palm Beach restaurant La Maze in 1927. The name purportedly arose when a socialite spilled the drink down the front of her white gown, exclaiming, “Now you can call me Bloody Mary, George!”

Another popular, and uncorroborated, theory holds that the cocktail’s moniker was borrowed from the murderous sixteenth-century persecutor of Protestants, Queen Mary Tudor.

Yet another debunked myth attributes the drink’s genesis to Hemingway. He may not have created it, but he did concoct his own recipe, as recorded in Ernest Hemingway: Selected Letters, 1917–1961 (1981). His version calls for a pitcher because “any smaller amount is worthless”:

Ernest Hemingway’s Bloody Mary

Ice

16 ounces good Russian vodka

16 ounces chilled tomato juice

1 tablespoon Worcester sauce (Lea and Perrins)

1½ ounce freshly squeezed lime juice

Celery salt

Cayenne pepper

Black pepper

In a pitcher half filled with ice, mix the vodka and tomato juice. Add the Worcester sauce and stir. Add the lime juice and stir. Add small amounts of celery salt, cayenne pepper, and black pepper. Stir and taste. If too powerful, weaken with more tomato juice. If it lacks authority, add more vodka.

He adds at the end: “For combatting a really terrific hangover increase the amount of Worcester sauce—but don’t lose the lovely color.”

SWEDEN AND ABSOLUT VODKA

Although Sweden did not adopt the designation of “vodka” until the 1950s, it too had been producing the spirit for centuries under the name brännvin (“burn-wine”). The country’s most famous brand, Absolut, was founded in 1879 by Lars Olsson Smith.

Lars Olsson Smith.

In 1979, under the guidance of entrepreneur Peter Ekelund and master distiller Börje Karlsson, Absolut was rebranded for a global launch that would alter the face of the spirits industry. Due in large part to the company’s ingenious advertising campaign, vodka in general would eventually eclipse scotch, gin, and wine in units sold worldwide.

YEARNING FOR THE GOOD OLD DAYS

Like Misha Vainberg, the protagonist in his best-selling novel Absurdistan (2006), Gary Shteyngart likes his vodka. Shteyngart was raised in Leningrad before immigrating to New York City at age seven, and true to his Russian roots, he prefers to drink vodka neat. His favorite brand is Russian Standard. “It doesn’t have a story about how it’s been triple-filtered through a diamond in a rhinoceros’s asshole, but it gets the job done.”

Gary Shteyngart.

In a 2006 interview with Modern Drunkard Magazine, Shteyngart laments the demise of the literary drinking tradition:

It’s so hard to be a writer these days. It’s so antiseptic. We’re this sterilized profession, we all know our Amazon.com rankings to the nearest digit. . . .

. . . There are so few people to drink with. The literary community is not backing me up here. I’m all alone. . . .

. . . The world I live in, in my mind, is still the world of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway. And Dostoyevsky. Drink it all away or gamble it all away at the drop of a hat. That doesn’t exist anymore.”

THE TASTELESS TITAN

Lawrence Osborne observes that vodka has become “the most successful man-made drug of all time.” Yet, despite its current supremacy as the world’s largest internationally traded spirit, drink purists (and writers outside of the Russian sphere of influence) have never really warmed up to it.

Vodka connoisseurs notwithstanding, the drink’s popularity lies not in what it possesses but in what it lacks—flavor. Proudly wearing its tastelessness on its sleeve, vodka has never inspired the hushed reverence associated with other fine spirits. Kingsley Amis, in Every Day Drinking, bemoans the underwhelming impression vodka leaves on the palate, explaining that it’s “for the benefit of those second-rate persons who don’t like the taste of gin, or indeed that of drink in general.”