Absinthe has a lovely colour, green. A glass of absinthe is as poetic as every other thing. What difference is there between a glass of absinthe and a sunset?

—Oscar Wilde (as told by Christian Krohg in In Little Day Trips to and from Paris, 1897)

Describing absinthe in his 1913 compendium of satirical definitions, Dictionnaire des idées reçues, Gustave Flaubert writes: “Extra-violent poison: a glass and you’re dead. Journalists drink it while they write their articles. Killed more soldiers than the Bedouins.”

Absinthe may be the most vilified, and misunderstood, spirit in the history of drink. No beverage has engendered more public hysteria, collective hand-wringing, or spurious claims. As such, the liquor also bears the distinction of being the most widely banned spirit of the last two hundred years.

And not surprisingly, thanks to its dangerous reputation, no other drink has been more romanticized or mythologized—or closely linked to the creative spirit. Numerous writers, poets, painters, and composers have all fallen under the sway of “the Green Muse.”

Poet Paul Verlaine dubbed the drink “the Green Fairy.”

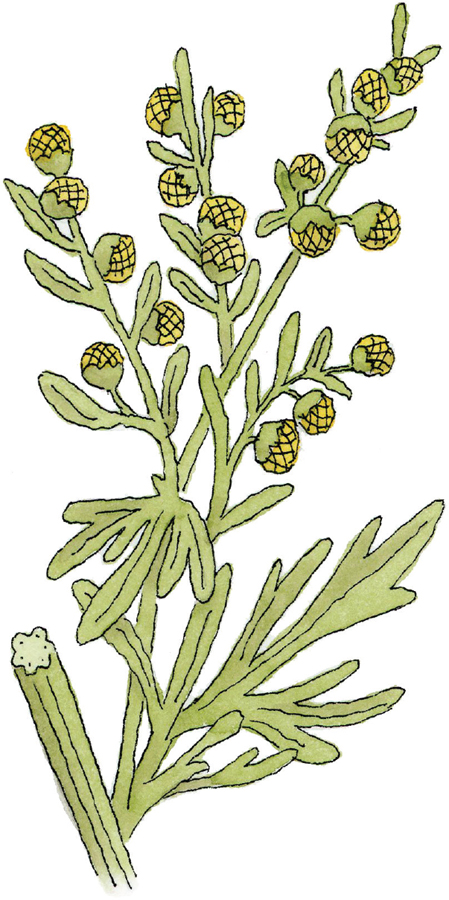

WORMWOOD

The key ingredient in absinthe is Artemisia absinthium, better known as wormwood, a woody perennial plant native to Mediterranean regions of Eurasia and northern Africa. Its distinctive green color comes from chlorophyll in the macerated wormwood leaves used to create the drink.

Wormwood.

Wormwood-infused spirits can be traced back to ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, where they were used primarily for medicinal purposes. In Naturalis historia (circa AD 77), Pliny the Elder detailed the many ailments wormwood could treat, as well as the many ways to prepare it, including a wormwood wine made by soaking the stems and leaves with grape must.

The word vermouth is derived from the German Wermut (wormwood). Vermouth, in its earliest form, was a wormwood-infused fortified wine produced in Germany and Hungary in the sixteenth century. Wormwood can still be found in some modern vermouth recipes.

But the prototype for modern absinthe would come centuries later, originating in the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel during the latter half of the eighteenth century. When French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud called absinthe the “sagebrush of the glaciers,” he was referring to Val-de-Travers, a chilly district within the canton where wormwood was plentiful.

The Swiss canton of Neuchâtel.

THE MYSTERIOUS ELIXIR OF VAL-DE-TRAVERS

Although the birthplace of absinthe is not in dispute, the individuals responsible for its creation are shrouded in myth and mystery. Scholars today are still trying to separate the messy tangle of facts from the fiction.

The most widely circulated legend involves a French military deserter named Pierre Ordinaire, who fled to the Swiss village of Couvet in Val-de-Travers in 1767. There he donned the guise of a country doctor (his medical credentials were dubious), gaining a favorable reputation after dispensing an herbal remedy composed of wormwood and aromatic plants. Many of his patients declared themselves radically cured after drinking the mysterious elixir. Another version of this story suggests that Ordinaire didn’t concoct the drink himself but co-opted the recipe from a local herbalist named Mademoiselle Henriod, who had already been selling the wormwood elixir for some time. The existence of an absinthe bottle from the time, labeled with the inscription “Superior quality absinthe extract from the single recipe of Marguerite Henriette Henriod,” supports the theory.

Marguerite Henriette Henriod.

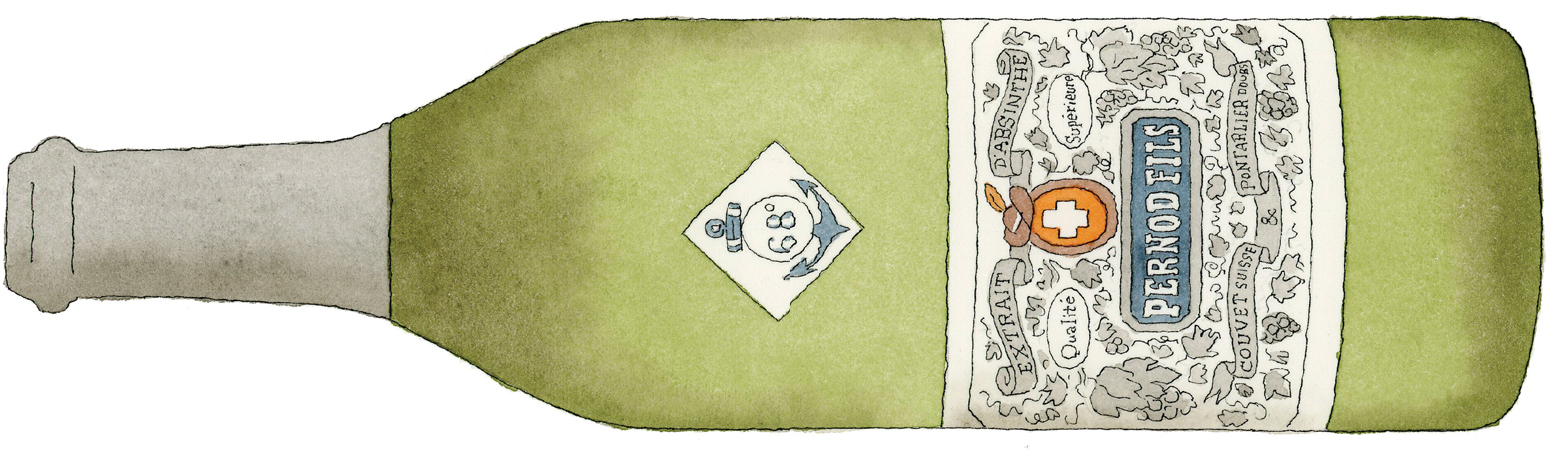

In 1798 a French merchant and customer of Henriod’s, Major Daniel Henri Dubied-Duval, recognizing the commercial potential of her elixir, established Dubied Père et Fils, the first mass-production absinthe distillery in Couvet, with the youngest of his five sons, Marcelin, and his son-in-law Henri-Louis Pernod.

Henri-Louis Pernod.

In 1802, in order to optimize the distribution of their product, Henri and Marcelin established Pernod Fils & Dubied in Pontarlier, France, near the Swiss border. After a split in their partnership in 1804, Henri joined forces with David Auguste Boiteux to established Pernod Fils & Boiteux Distillery. This would become one of the most popular brands of absinthe up until 1914, when the drink was banned in France.

FRENCH MEDICINE

Absinthe was marketed as a health tonic by Pernod and other producers, and the French military adopted it for medicinal purposes. During the French conquest of Algeria (1830–1847), soldiers were provided regular field rations of absinthe to ward off fevers, malaria, and dysentery. Of course, they were soon drinking it for nonmedicinal purposes as well. Soldiers who survived the war took their thirst for the powerful intoxicant back home with them, sparking an upsurge in production all over France.

THE GREAT FRENCH WINE BLIGHT

In the mid-nineteenth century a massive outbreak of phylloxera (a vine-eating aphid) swept French vineyards, causing the Great French Wine Blight, which nearly wiped out the country’s wine industry, causing the prices to skyrocket. The 1863 infestation was not effectively halted until the 1890s. The resulting wine shortage turned out to be a boon for the absinthe industry. Before the blight, the spirit had been a pricey indulgence reserved for the middle classes, but absinthe producers quickly stepped in to fill the wine void. Along with a massive increase in production came a sharp drop in price. The Green Fairy was suddenly accessible to a burgeoning bohemian subculture of writers, poets, and artists who could no longer afford wine.

The Phylloxera aphid as depicted in an Edward Sambourne cartoon from Punch, 1890.

THE GREEN HOUR

Absinthe helped fuel the spread of café culture throughout Europe—by 1869, thousands of cabarets and cafés existed in Paris alone. The drink became fashionable as a potent aperitif consumed in mid-to-late afternoon, and this time of day soon became known as l’heure verte (“the green hour”). Another byproduct of absinthe’s growing popularity was the street prostitution that organized around cafés and the green hour. The café, previously an institution known for political and intellectual exchange, was now becoming a center for pleasure as well.

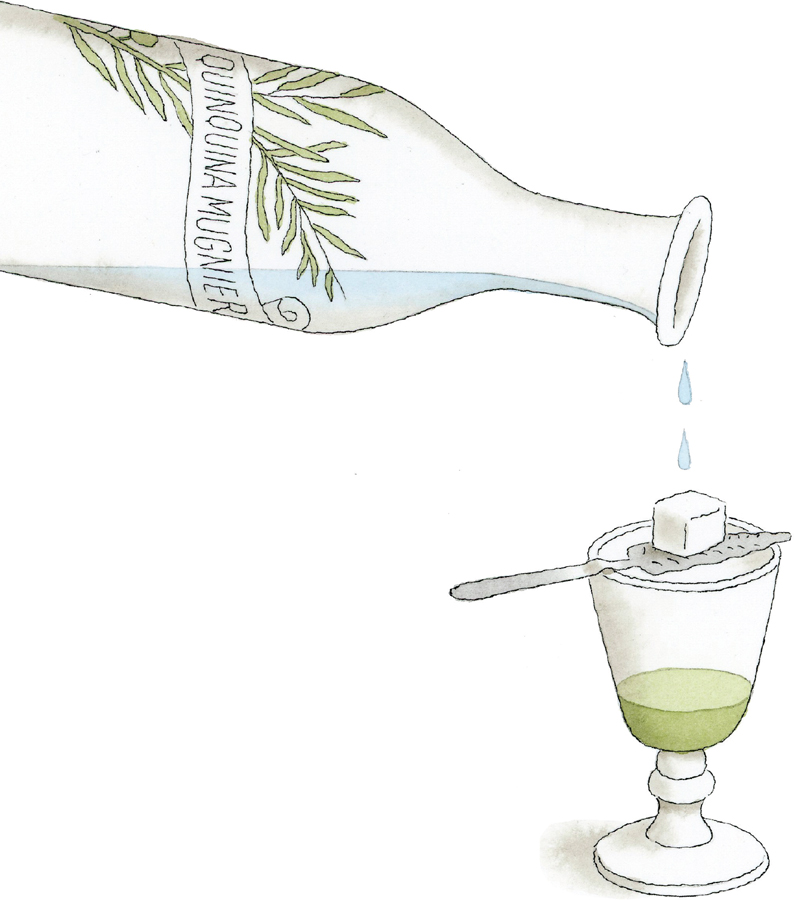

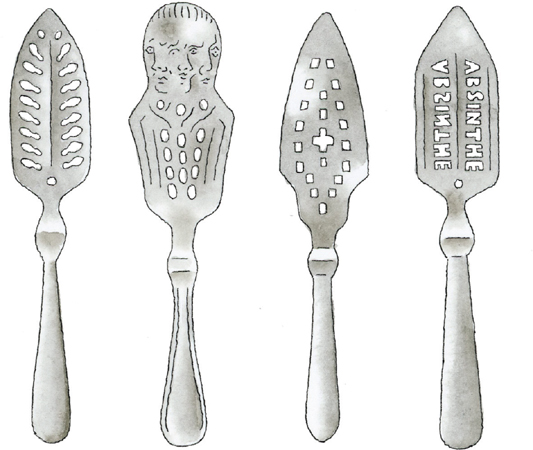

A ritual developed around the consumption of absinthe (giving rise to a fetishistic appetite for absinthe-related paraphernalia):

Part of the drink’s appeal was aesthetic—as water was added to the absinthe, the deep green color of the liquor turned milky and iridescent.

Mixologists have created numerous cocktail recipes featuring absinthe, but the basic water-drip preparation is the classic way to drink it.

Absinthe spoons.

BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY

Absinthe reached its zenith of popularity during the Belle Époque (typically dated from the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 to the outbreak of World War I in 1914) in Paris, where a constellation of distinguished writers, artists, and musicians succumbed to the allure of the Green Fairy. They were part of a revolutionary counterculture movement that rejected classical idealization in the arts in favor of a gritty realism that crossed class and gender lines.

A cancan dancer from the legendary Parisian cabaret Moulin Rouge, founded in 1889.

The French poet and novelist Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de bohème (1845), as well as French composer George Bizet’s opera Carmen (1876), did much to popularize the so-called bohemian lifestyle of the counterculture movement. The decadence and heavy drinking of many of the artists involved would eventually sully absinthe’s reputation, but it did little to tarnish our cultural fascination with the bohemian demimonde.

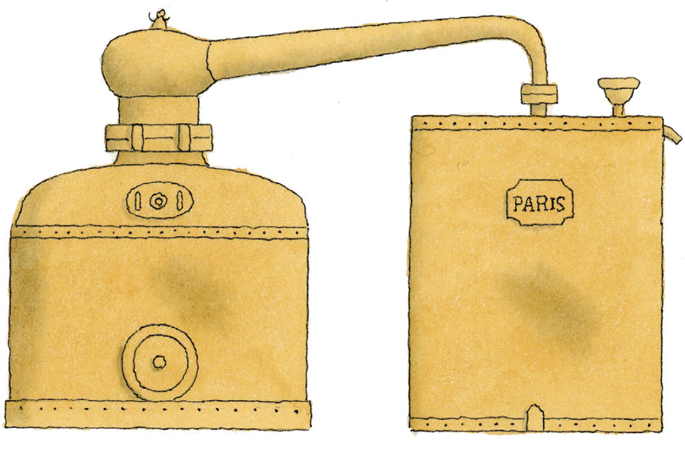

Absinthe still manufactured in Paris, 1881.

LA VIE BOHÈME: THE WRITERS AND ARTISTS OF MONTMARTRE

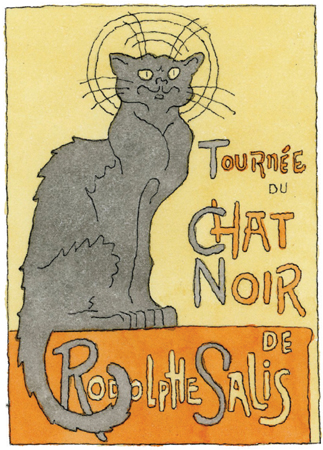

The Montmartre district of Paris, situated on a large hill in the city’s Eighteenth Arrondissement, was Europe’s bohemian epicenter. Absinthe flowed freely at Le Chat Noir in Montmartre, founded in 1881 by impresario Rodolphe Salis and considered the first modern cabaret. Paul Verlaine, Spanish painter Pablo Picasso, and French composer Erik Satie were among Le Chat Noir’s many illustrious patrons.

The iconic 1896 poster by Théophile Steinlen promoting Le Chat Noir’s troupe of cabaret entertainers.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was another regular, and he was known for keeping glass vials of absinthe in the hollowed-out custom-made canes that he carried, referred to today as “Toulouse-Lautrec” or “tippling” canes. One of his favorite cocktails was called the earthquake, a mixture of absinthe and Cognac.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

The “tippling” cane.

In Charles Baudelaire’s “The Poison,” from his 1857 collection of poetry Les fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), absinthe (the poison of the title) ranks above wine and opium:

All that is not equal to the poison which flows

From your eyes, from your green eyes,

Lakes where my soul trembles and sees its evil side . . .

My dreams come in multitude

To slake their thirst in those bitter gulfs.

French symbolist writer Alfred Jarry, best known for his play Ubu roi (King Ubu) (1896), insisted on drinking his absinthe straight, referring to it as “holy water.”

Alfred Jarry.

Guy de Maupassant partook, as did many of his characters in short stories such as “A Queer Night in Paris”: “M. Saval sat down at some distance from them and waited, for the hour of taking absinthe was at hand.”

Fellow symbolist and Dutch poet Gustave Kahn (1859–1936) expressed his devotion in free verse:

Absinthe, mother of all happiness,

O infinite liquor, you glint in my glass green

and pale like the eyes of the mistress

I once loved. . . .

The hirsute Gustave Kahn.

Edgar Degas’s famous 1876 painting L’absinthe, which hangs in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, portrays two of his friends drinking at their favorite haunt, the Café de la Nouvelles Athènes on the Place Pigalle.

In writing his novel L’assommoir, a study of alcoholism among the poor of Paris, the French writer Émile Zola credited Degas for some the book’s imagery, telling him, “I quite plainly described some of your pictures in more than one place in my pages.”

Émile Zola.

Nana, the prostitute from Zola’s novel by the same name (1880), drinks absinthe to forget “the beastliness of men.”

French poet Raoul Ponchon declares in his 1886 poem “Absinthe”:

Absinthe, I adore you, truly!

It seems, when I drink you,

I inhale the young forest’s soul,

During the beautiful green season.

Your perfume disconcerts me

And in your opalescence

I see the full heavens of yore

As through an open door.

Raoul Ponchon.

French painter Paul Gaugin, in a letter to a friend in 1897, wrote: “I sit at my door, smoking a cigarette and sipping my absinthe, and I enjoy every day without a care in the world.”

Vincent Van Gogh was introduced to the spirit by Toulouse-Lautrec and Gaugin. Historians speculate that he may have been addicted to chemicals of the turpene class—present in camphor, turpentine, and absinthe. This craving would explain his known propensity to ingest paint and turpentine as well as absinthe.

Picasso arrived in Paris in 1901 at age twenty and went on to create numerous paintings depicting absinthe drinkers, including Woman Drinking Absinthe (1901), from his so-called blue period.

One of six copies of Glass of Absinthe, sculptures cast in bronze, each decorated uniquely, by Pablo Picasso, Paris 1914.

PARISIAN PARTY ANIMALS

Absinthe mythology owes much to the tempestuous relationship between poets Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine, who cut a drunken swath through bohemian Paris. Rimbaud, the enfant terrible, would come to embody the danger, mystery, and romance associated with the liquor. Allen Ginsberg later called Rimbaud “the first punk,” and an inspiration for the Beat movement of the 1950s. Rimbaud would also influence the surrealists, and later songwriters such as Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison, and Patti Smith. Verlaine’s fame, although he enjoyed an esteemed literary reputation in his day, will forever be linked to Rimbaud.

Arthur Rimbaud.

In 1871, at age seventeen, a then unknown Arthur Rimbaud, from the Ardennes region of France, sent some of his poems to several established poets in Paris. Among the poems included in his correspondence was the now famous “Le bateau ivre” (“The Drunken Boat”), written when he was sixteen.

Paul Verlaine.

His only response came from Paul Verlaine, a distinguished symbolist poet who was fourteen years his senior. He was intrigued by the precocious young talent, and invited Rimbaud to Paris. “Come dear great soul. We await you; we desire you,” he wrote back, then sent him a one-way ticket.

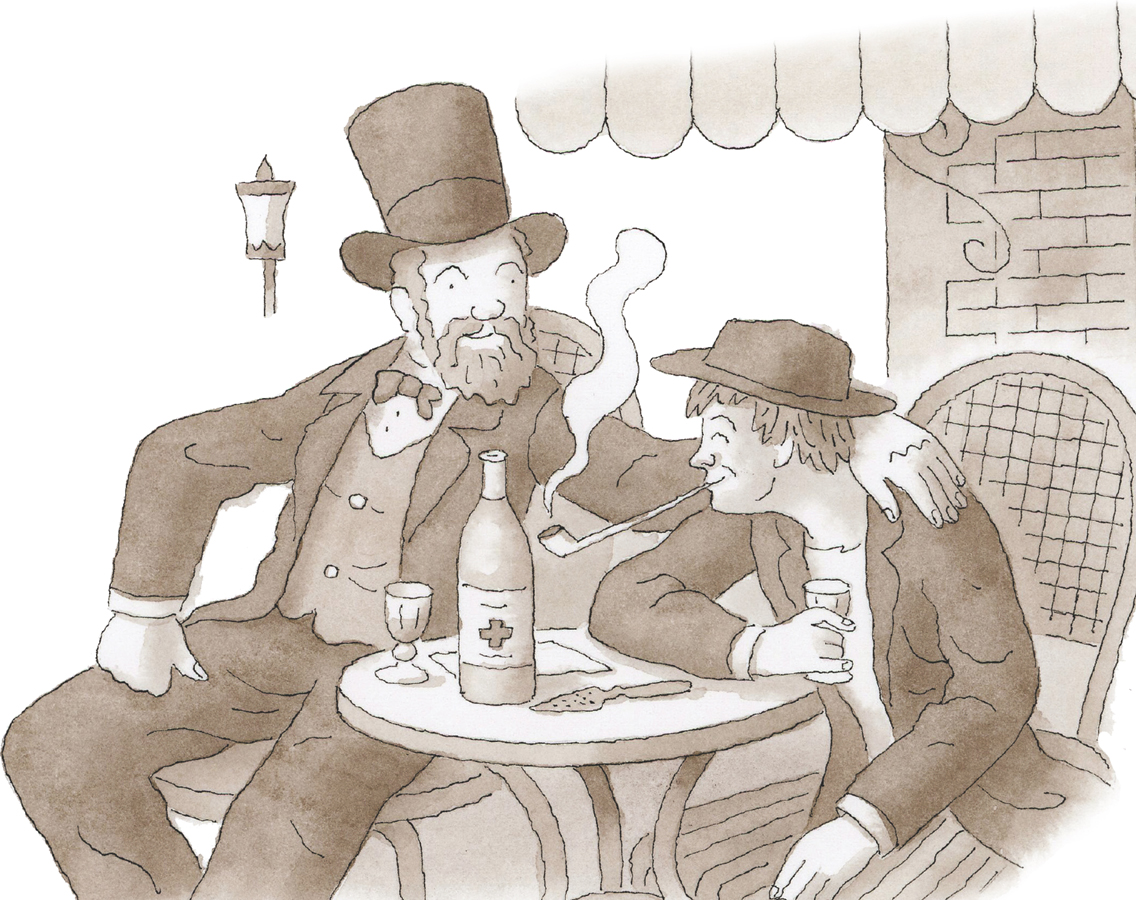

Although few references to absinthe appear in Rimbaud’s work, it is well known that he became entranced by the Green Fairy soon after meeting Verlaine. The duo became regulars at Le Café du Rat Mort (the Dead Rat Café) on the Place Pigalle in Paris, gaining a reputation around the city for their drunken antics and boorish behavior. Verlaine once said, “If I drink, it is to get drunk, not to drink.”

The ubiquitous clay pipe seen in visual depictions of Rimbaud was a Scouflaire, a popular French brand of the time.

Rimbaud considered the consumption of alcohol and other intoxicants, such as hashish, not as a recreational pursuit but as essential to his writing process. He was looking for a new poetic language. Before departing for Paris he had written to a friend: “The poet makes himself a seer by a long, prodigious, and rational disordering of the senses.” In Paris, absinthe was a readily available means to this end.

The London flat at 8 Royal College Street, where the two poets lived briefly in 1873.

Despite Verlaine’s marriage to Mathilde Mauté, he and Rimbaud engaged in a brief but turbulent love affair. Verlaine was enchanted by the younger poet’s restless genius and libertine excesses. Rimbaud, in a role reversal, saw himself as Verlaine’s mentor, urging the older poet to purge his work of its sentimental bourgeois sensibilities.

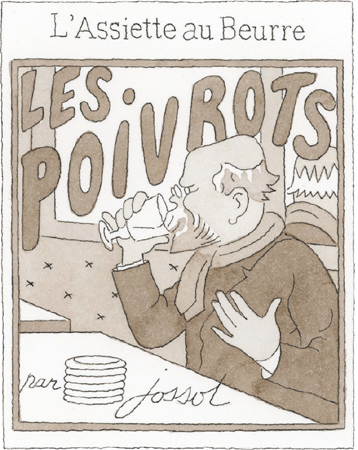

Les poivrots (Drunkards). Verlaine is depicted (by the artist Gustave-Henri Jossot) on a 1907 cover of L’Assiette au Beurre, a French satirical magazine.

Verlaine abandoned his wife and infant child in 1872 to roam around northern France and Belgium with Rimbaud. The two quarreled often, and in 1873 Rimbaud needed a break, decamping to his family’s farm in Roche. There he wrote a large portion of his extended prose poem Une saison en enfer (A Season in Hell).

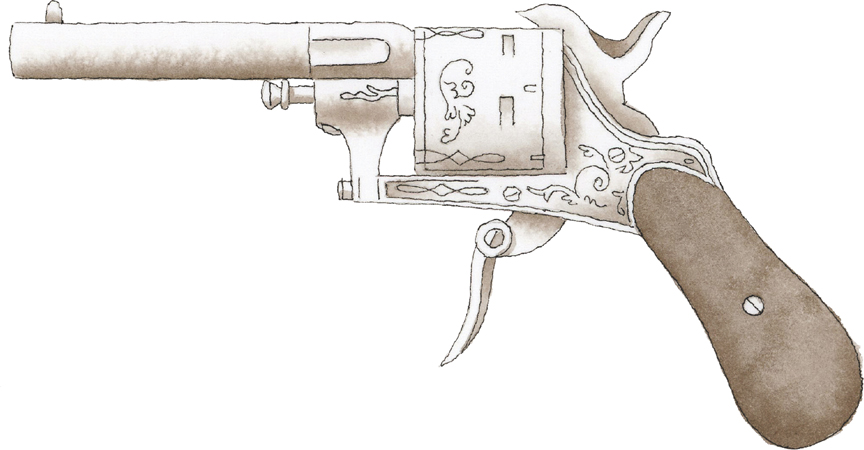

Several weeks later he rejoined Verlaine, and they traveled together through London and Belgium. Their stormy relationship ended violently in Brussels when Verlaine, in a drunken jealous rage, fired two shots from a revolver, wounding Rimbaud in the left wrist. Verlaine was arrested and served two years in prison, where he renounced his bohemian life and converted to Catholicism.

The most famous gun in French literature—the Lefaucheux revolver that Verlaine used to shoot Rimbaud—was sold at Christie’s auction house in 2016 for $460,000.

For the next two years Rimbaud worked on his groundbreaking suite of prose poems, Illuminations, before abandoning poetry altogether at age twenty-one. He then disappeared, wandering around the Horn of Africa on foot and supporting himself as a trader and an arms dealer. He succumbed to bone cancer in Marseilles at age thirty-seven.

Rimbaud’s complete works were published in 1895 under Verlaine’s supervision, making the deceased poet famous. Absinthe remained Verlaine’s truest companion until the end of his days. He died an alcoholic, and in poverty, in Paris at the age of fifty-one.

ABSINTHE IN AMERICA

The sazerac.

Absinthe found its way to America in 1837, by way of “the Little Paris of North America,” New Orleans. It was first served at a saloon called Aleix’s Coffee House, which became known around town as the Absinthe Room. Later, in 1890, it was officially rechristened the Old Absinthe House. The bar eventually became a local landmark, where the sazerac, a Cognac/absinthe concoction regarded by some drink historians as America’s oldest cocktail, was served to the likes of Mark Twain, William Thackeray, Walt Whitman, and Oscar Wilde.

THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GREEN

Oscar Wilde occupies a central position in absinthe lore due to several memorable descriptions of the drink that are attributed to him. However, none of these quotes can be traced to anything he wrote but rather to hearsay from friends and other writers.

Oscar Wilde.

Wilde fled to France in 1897 following his release from prison in England on indecency charges. The famed author of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) and The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) was not known to be a heavy drinker, and was likely introduced to absinthe in his adopted country.

One of Wilde’s most famous musings on the subject is recounted by his friend Ada Leverson, in her book Letters to the Sphinx from Oscar Wilde: With Reminiscences of the Author (1930). It concerns how absinthe alters the imbiber’s perception of the world: “After the first glass you see things as you wish they were. After the second, you see things as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.”

Among the many myths that continue to circulate around Edgar Allan Poe is that he was a heavy absinthe drinker. Absinthe consumption may dovetail with the unhinged-artist narrative, but no evidence exists to suggest he drank it, or was even aware of it.

DEVIL IN A BOTTLE

By the late 1800s, absinthe’s rise in popularity was accompanied by increasing hysteria and opposition to the drink as a societal menace. Much like the PCP epidemic of the 1970s, or the Reefer Madness panic of the 1930s, all manner of wild and erratic behavior was ascribed to its alleged psychoactive properties. The spirit, containing a chemical toxin called thujone (the active ingredient in wormwood oil), was believed to disrupt the central nervous system.

An 1869 pharmaceutical journal in London quoted from a Pall Mall Gazette article detailing the ill effects of absinthe drinking:

After a while the digestive organs become deranged. . . . Now ensues a constant feeling of uneasiness, a painful anxiety, accompanied by sensations of giddiness and tinglings in the ears; and as the day declines, hallucinations of sight and hearing begin. . . . his brain affected by a sort of sluggishness which indicates approaching idiocy . . . in the end come entire loss of intellect, general paralysis, and death.

It has often been suggested that the ingestion of thujone, by way of absinthe consumption, may have exacerbated Vincent Van Gogh’s psychosis, thus precipitating the infamous ear-slicing episode of 1888. The truth may never be known, however, the incident was later used as propaganda in the anti-absinthe campaign.

Vincent Van Gogh.

English novelist Maria Corelli’s Wormwood: A Drama of Paris (1890) follows a promising young Parisian man who falls prey to absinthe’s seductive, and ultimately ruinous, powers. The novel’s lurid tale of debauchery, murder, suicide, and addiction pandered to British Francophobia, as well as the public’s fascination with fin-de-siècle Parisian decadence.

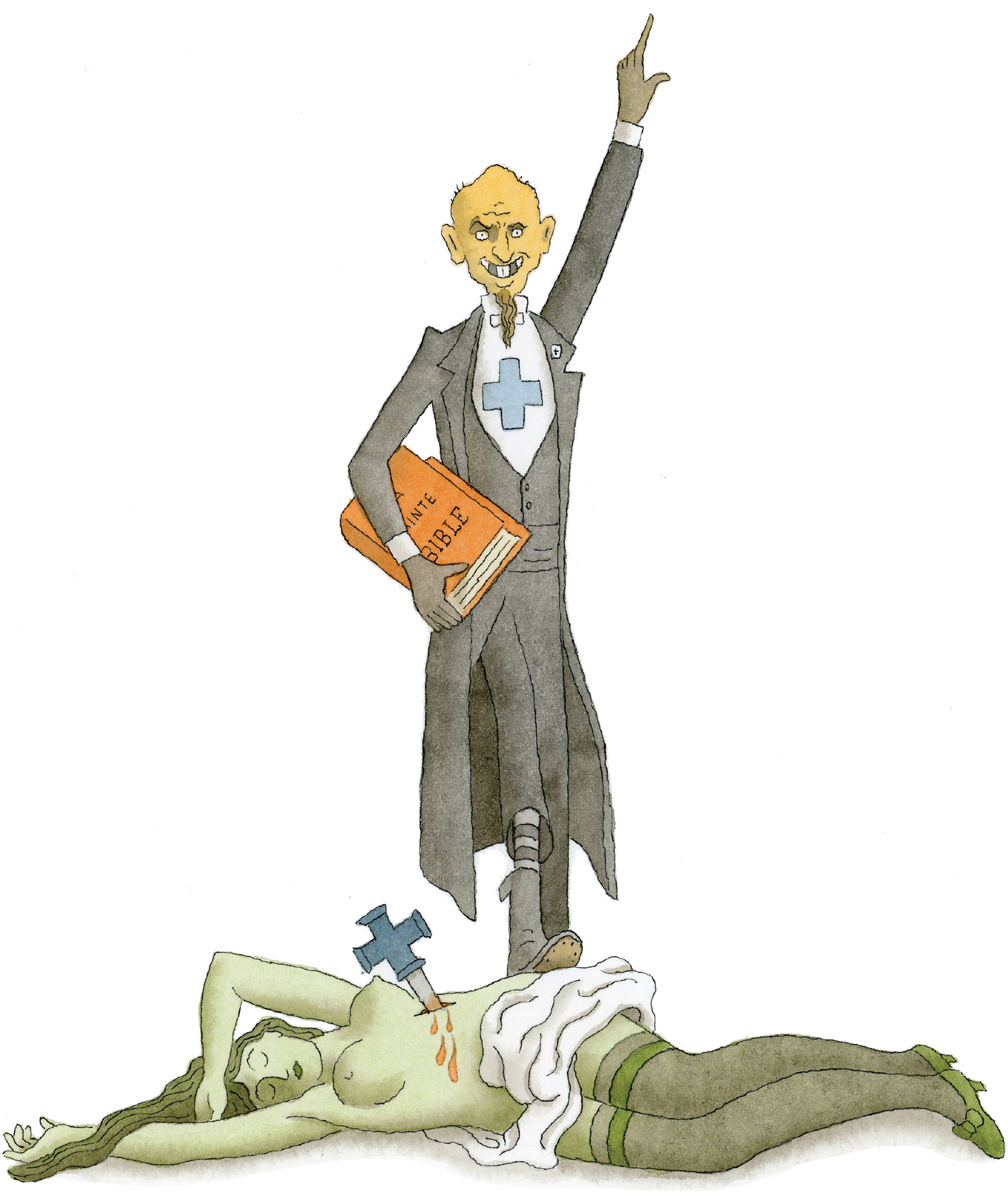

“Absinthe is death!,” a poster by F. Monod, 1905.

In 1905 a Swiss farmer named Jean Lanfray shot his wife after a day of drinking wine, Cognac, and absinthe. The press sensationalized the crime, dubbing it “the absinthe murder.” Europe’s temperance movement seized upon the incident and demonized the spirit as not only a health peril but a moral contaminant. The panic that ensued led to petitions calling to ban the liquor. Belgium outlawed absinthe in 1905, followed by Switzerland and the Netherlands in 1910 and the United States in 1912. France tried raising taxes on absinthe in hopes of depressing demand (in 1907 the spirit contributed sixty million francs in taxes to French coffers), before finally succumbing to a ban in 1915.

After being forced to comply with anti-wormwood laws, absinthe producer Pernod created his famous pastis in 1922, still popular today. It retains the anise character of absinthe but without the wormwood.

The Slain Green Fairy, from a 1910 satirical poster by artist Albert Gantner, critical of the ban on absinthe in prohibitionist Switzerland—the blue cross was the symbol of La Croix Bleue, a powerful temperance organization.

HEMINGWAY AND ABSINTHE

Absinthe could still be obtained illicitly in Paris following the ban, but Ernest Hemingway most likely made his acquaintance with the spirit while working on assignment in Spain, one of the few European countries where it remained legal.

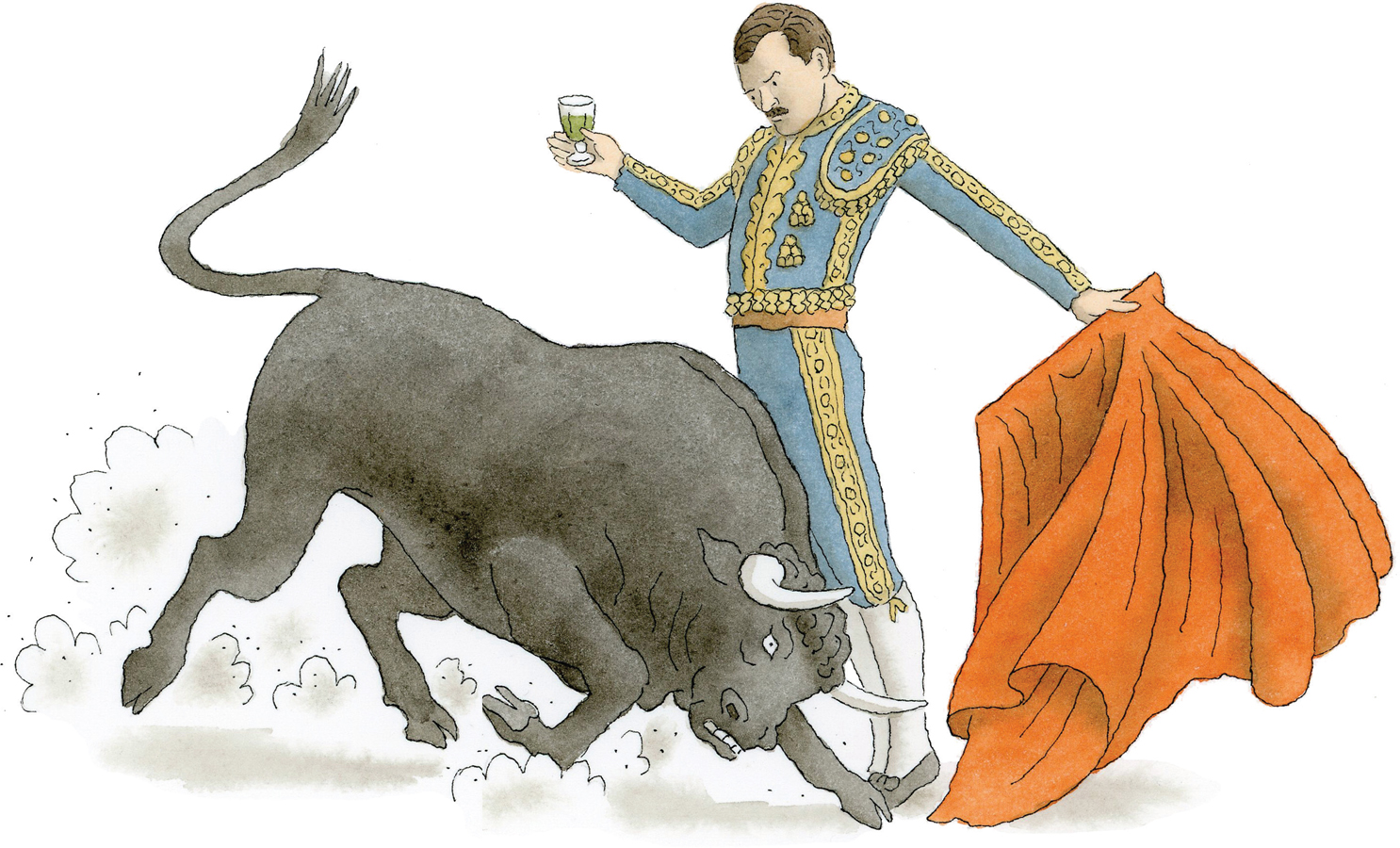

The Green Fairy makes an appearance in The Sun Also Rises—the smitten Jake Barnes drinks absinthe to numb the pain following Lady Brett’s tryst with a Spanish bullfighter.

First edition, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1940.

Hemingway would enjoy absinthe while working as a journalist covering the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s. And the spirit again finds its way into his novel inspired by the experience, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940)—his character Robert Jordan sips absinthe from his canteen as a respite from war: “One cup of it took the place of the evening papers, of all the old evenings in cafés, of all chestnut trees that would be in bloom now in this month . . . of all the things he had enjoyed and forgotten and that came back to him when he tasted that opaque, bitter, tongue-numbing, brain-warming, stomach-warming, idea-changing liquid alchemy.”

A 1935 book entitled So Red the Nose: or—Breath in the Afternoon, a compilation of cocktail recipes by famous authors, included a recipe from Hemingway called “Death in the Afternoon.” The drink took its name from Hemingway’s 1932 book of the same name about Spanish bullfighting: “Pour one jigger absinthe into a Champagne glass. Add iced Champagne until it attains the proper opalescent milkiness. Drink three to five of these slowly.”

An editor’s note at the end of the recipe states, “After six of these cocktails The Sun Also Rises.”

THE GREEN FAIRY REVIVAL

Changing attitudes have led to the relaxation and overturning of laws banning absinthe. In 1988 the European Union made the spirit legal again, so long as thujone content did not exceed ten milligrams/kilograms. The modern absinthe revival was sparked in the 1990s when British importer BBH Spirits, recognizing that the United Kingdom had never formally banned the spirit, began importing Hill’s Absinth from the Czech Republic. This “Bohemian-style absinthe” had little resemblance to classic absinthe but paved the way for brands more faithful to original recipes.

In 2005, Switzerland, absinthe’s country of origin, made it legal again to manufacture and sell the spirit (after years of bootlegged production). In 2007, under pressure from distillers and distributers, the United States became the last major Western country to lift the ban. In late 2007 the first American absinthe brand, St. George Absinthe Verte from the St. George distillery in California, made its debut, opening the door for the numerous microdistilleries around the country that now produce it.

Absinthe’s heyday as an enigmatic bohemian muse is long over, but today it enjoys a modest resurgence as both fabled icon and hipster curiosity.