Tequila, scorpion honey, harsh dew of the doglands, essence of Aztec, crema de cacti; tequila, oily and thermal like the sun in solution; tequila, liquid geometry of passion; Tequila, the buzzard god who copulates in midair with the ascending souls of dying virgins; tequila, firebug in the house of good taste; O tequila, savage water of sorcery, what confusion and mischief your sly, rebellious drops do generate!

—Tom Robbins, Still Life with Woodpecker (1980)

Late Aztec period (AD 1350–1520) ceramic pulque vessel.

In spite of a rich history that goes back centuries to pre-Columbian times, mezcal (or mescal)—and its best-known style, tequila—remained largely unknown outside of Mexico prior to World War I.

Consequently, its backstory as a creative lubricant for modern-era writers in North America and Europe doesn’t run nearly as deep or as wide as the other spirits written about in this volume. Today mezcal and tequila are treasured symbols of Mexico’s national identity.

Mayahuel is the Aztec goddess of the maguey plant and fertility and was often depicted with many breasts—a reference to the milky sap of the plant.

THE MESOAMERICAN NECTAR OF THE GODS

The story of mezcal begins around 1000 BC with the Aztecs, Mayans, Huastecs, and other cultures in ancient Mesoamerica fermenting the sap of the agave plant, also known as maguey, to create a milky drink called pulque. According to ancient myth, the sacred beverage was bestowed upon humankind by the Aztec deity Quetzalcoatl to lift spirits. Pulque was the forerunner of modern mezcal and tequila.

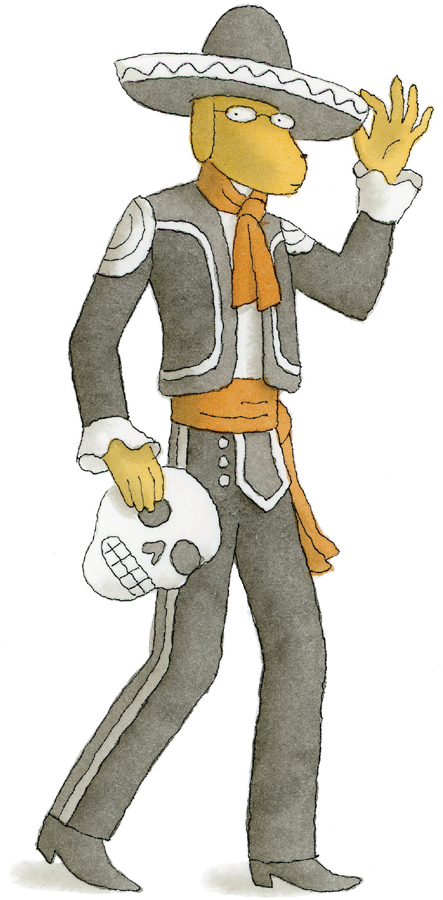

Quezalcoatl as depicted in the sixteenth-century Codex Maglabechiano, an Aztec religious document.

For more than two thousand years the indigenous people of the Aztec Empire enjoyed the drink all to themselves, until Hernán Cortés and company arrived in 1521 to spoil the party. In between raping and plundering, the Spanish conquistadors found time to enjoy the local beverage.

Hernán Cortés.

They liked it enough to attempt shipping it back to Spain, however, due to agave’s bacterial composition, the pulque soured too quickly to survive the long voyage across the Atlantic.

MEXICO’S EARLY DISTILLERIES

In the 1600s the marquis of Altamira built the first large-scale tequila distillery in what is now Tequila, Jalisco. The region’s climate and red volcanic soil were ideally suited to the cultivation of blue agave. Two of today’s largest tequila brands were originally launched in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The first, Jose Cuervo, was originally produced as mezcal wine by the Cuervo family for several decades, before José María Guadalupe de Cuervo secured from the Spanish crown the first license to produce it in 1795. Then, in 1873, the Sauza family became the first distiller to call the drink made from the blue agave plant “tequila.” Don Cenobio Sauza, dubbed “the father of tequila,” had identified blue agave as the best variety for producing the spirit.

Agave tequilana.

AMERICA—MEET TEQUILA!

Don Cenobio Sauza was the first to export tequila to America, introducing it as vino mescal at the World’s Columbian Exposition, aka the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Debuting alongside Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit chewing gum and Cracker Jacks, the spirit garnered a total of seven awards.

A metal Christopher Columbus corkscrew, one of many souvenirs available at the 1893 World’s Fair.

In 1916 during World War I, American troops training along the United States/Mexico border made their acquaintance with tequila in the Mexican towns of Tijuana, Juárez, Nuevo Laredo, and Matamoros. The spirit received a boost in popularity during Prohibition when tequileros smuggled it across the border through south Texas, and again during World War II when it was the beneficiary of decreased overseas liquor shipments.

A decade later, in 1958, the spirit was cemented in the pop culture firmament with the release of “Tequila,” a Latin-flavored, one-word instrumental B-side single by the Champs. It would reach number one on the Billboard pop chart.

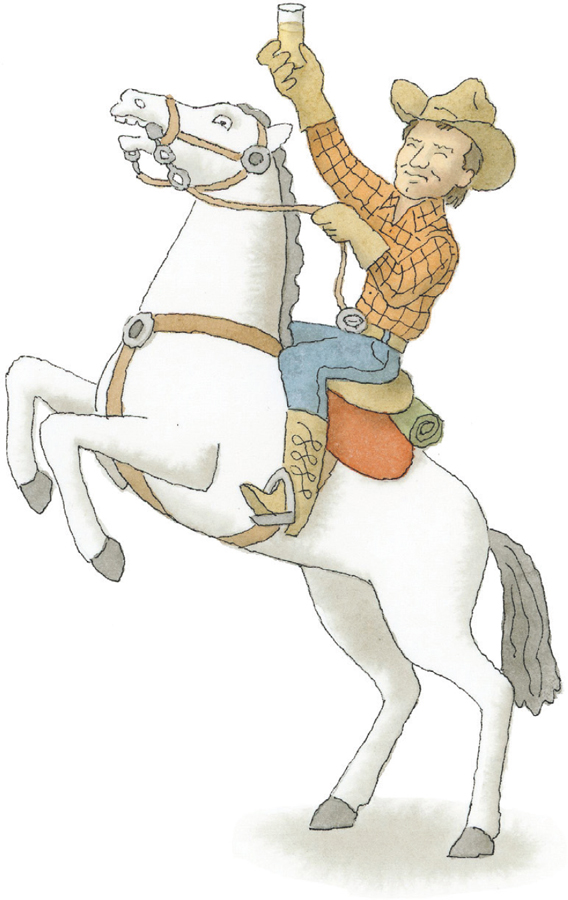

Prohibition-era tequileros—tequila smugglers—could pack fifty bottles (individually wrapped in twine bags to muffle the telltale sound of clanking glass) on a single mule or donkey.

MEZCAL MAN

In Western literature, the greatest work of mezcal-infused fiction is Malcolm Lowry’s 1947 novel Under the Volcano, which the author spent nearly ten years of his life writing and rewriting. Under the Volcano takes place on November 2, 1938, Mexico’s Day of the Dead, and details the final hours of the life of Geoffrey Firmin, a British consul living in the small Mexican town of Quauhnahuac (the Nahuatl name for Cuernavaca). Firmin is a doomed alcoholic, inhabiting a mezcal-fueled dream world that plays into the myth of the spirit’s psychotropic powers. For Firmin, mezcal not only numbs his pain, it serves as a conduit to moments of revelatory truth and beauty: “The drifting mists all seemed to be dancing, through the elusive subtleties of ribboned light, among the detached shreds of rainbows floating.”

Written in a dense and allusive prose style, with nods to T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and the daylong odyssey of Joyce’s Ulysses, the novel sits at position 11 on the Modern Library’s list of the 100 Best Novels of the twentieth century.

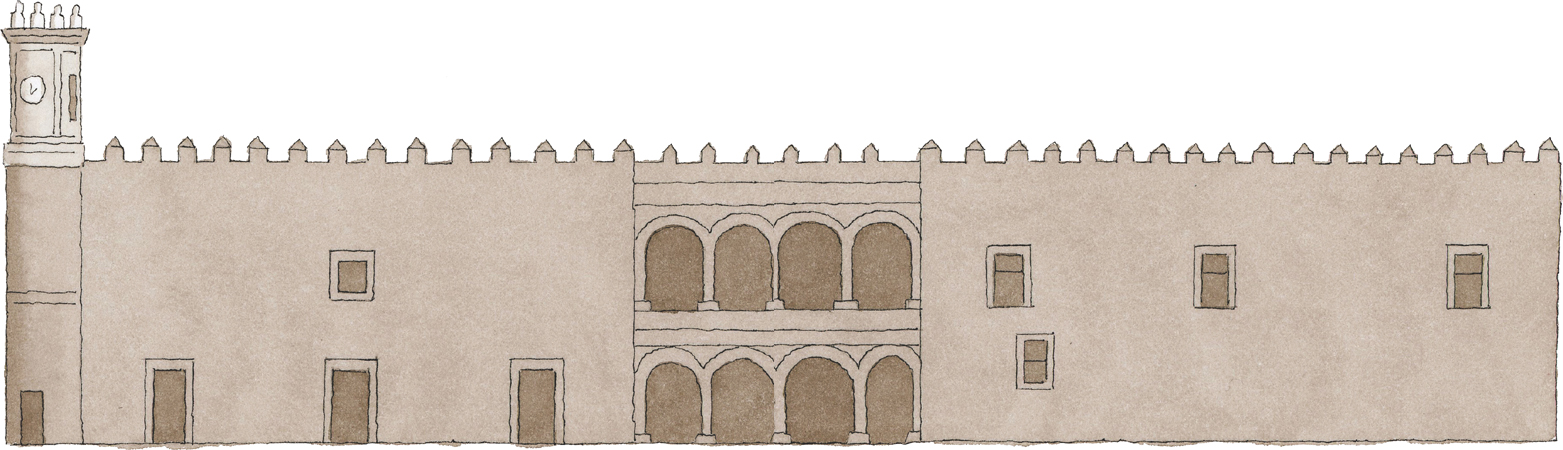

The Palace of Cortés in Cuernavaca, the fortified residence of conqueror Hernán Cortés, built in 1526.

Malcolm Lowry’s childhood hews closely to the oft-repeated story line of a young artist chafing under the restraints of a conservative, domineering father. The son of a wealthy cotton broker, Lowry spent his formative years (1923–27) at the Leys School near Cambridge, England, the setting for James Hilton’s popular novel and play Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1934). At school he discovered the twin passions that would govern his life—writing and booze. He is said to have begun drinking at the age of fourteen.

Later, in search of life experience, Lowry became a deckhand aboard a steamer to the Far East, before resuming his studies at St. Catherine’s College in Cambridge.

The twenty-year-old Lowry sent an effusive fan letter to his idol, the American poet, novelist, and fellow tippler Conrad Aiken. This would spark a lifelong friendship between the two. The title of Lowry’s first novel, Ultramarine (1933), was a playful reference to Aiken’s 1927 novel Blue Voyage, a book he adored.

Lowry likely got his hands on this British first edition, published by Gerald Howe, London, 1927.

On a trip to Spain with Aiken, Lowry met his first wife, an American named Jan Gabrial. They were married in France in 1934, but it was a stormy relationship, largely due to his drinking.

Two years later, following an estrangement and in a final attempt to salvage their marriage, the couple moved to the Mexican city of Cuernavaca in the state of Oaxaca.

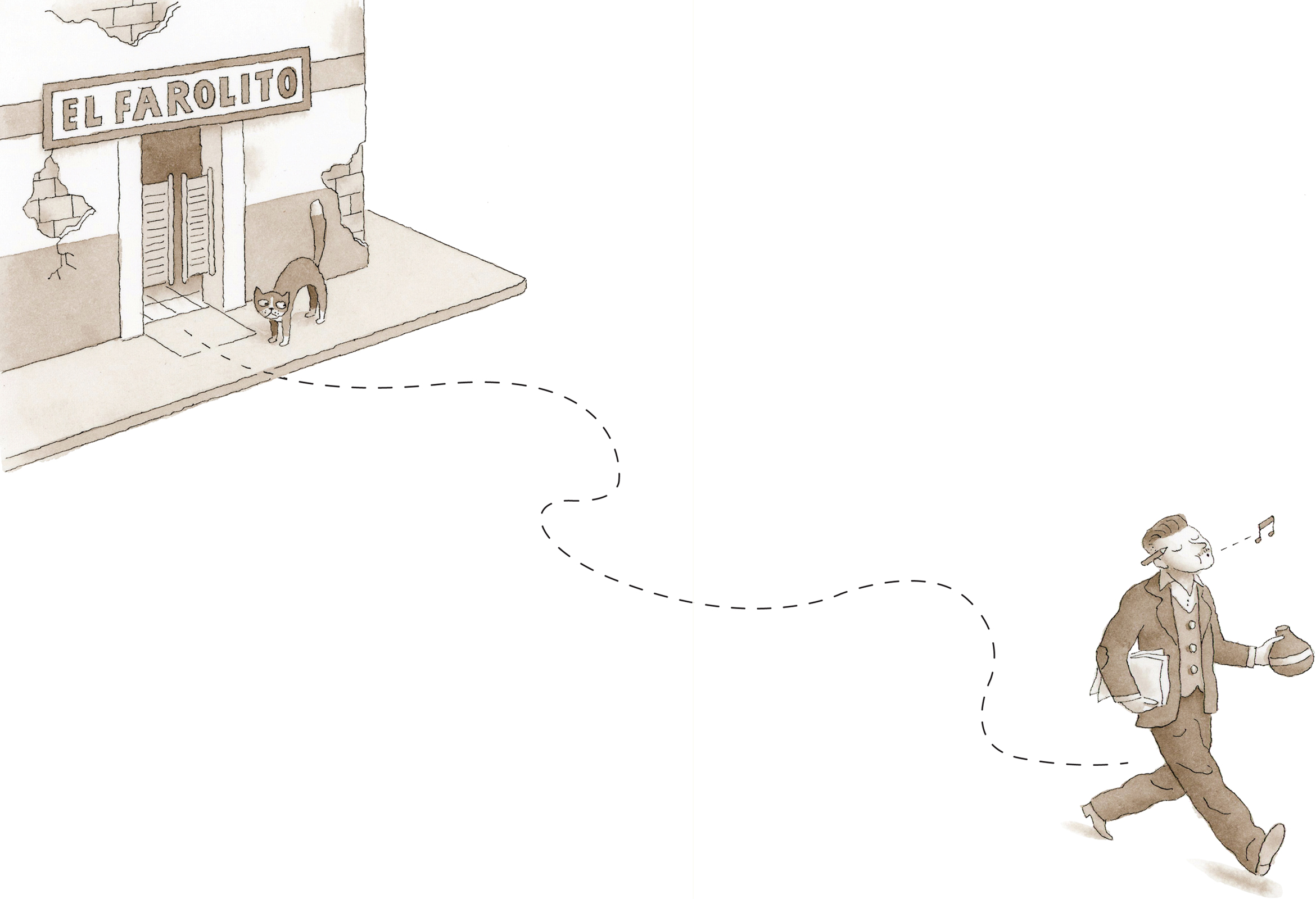

Living in mezcal’s ancestral homeland, Lowry readily availed himself of the local agave distillates. In the 1930s the spirit lacked the smoothness of modern mezcal, and in Under the Volcano the consul describes it as tasting “like ten yards of barbed wire fence.” Unlike most drunks, Lowry was a dedicated writer when under the influence, seldom leaving a cantina without at least four pages of handwritten notes.

In another passage from Volcano, he describes the consul’s view from his cantina barstool: “Behind the bar hung, by a clamped swivel, a beautiful Oaxaqueñan gourd of mescal de olla, from which his drink had been measured. Ranged on either side stood bottles of Tenampa, Berreteaga, Tequila Añejo. . . . He was safe here; this was the place he loved—sanctuary, the paradise of his despair.”

Barro negro (black clay) mezcal gourd, Oaxaca, circa 1930s.

His wife would walk out on him a year later. In the depths of despair, he was nonetheless writing with renewed vigor, developing what would become an early version of Under the Volcano. His excessive drinking eventually landed him in an Oaxacan jail, and he was subsequently deported in 1938.

Margerie Bonner.

He retreated to Los Angeles, where he continued to work on drafts of Volcano. He hired an agent to shop the manuscript around, but it was rejected by twelve publishers. In the midst of these struggles, he met and fell in love with Margerie Bonner, an aspiring mystery writer. When Lowry’s American visa expired, he crossed the border to the north, eventually settling in a squatter’s cabin in Dollarton, British Colombia. Bonner soon followed, and they were married on December 2, 1940. Despite marital tensions, the nearly fifteen years the couple spent in Canada would be the happiest of Lowry’s life.

Lowry devoted himself exclusively to revising his magnum opus, with considerable editorial assistance from Bonner. “We work together on it day and night,” he wrote to Aiken. By the end of 1944, the final draft was complete.

J. G. Posada’s Day of the Dead Calavera Oaxaqueña (Skull from Oaxaca), 1910.

Under the Volcano was finally published in 1947 to wide acclaim, and its stature would only grow with time. Lowry, hailed as a successor to Joyce, enjoyed a moment of fame but was soon lost in alcohol again. In a letter to Margerie’s mother he wrote, “Success may be the worst possible thing that could happen to any serious author.”

First edition, Reynal & Hitchcock, New York, 1947.

He worried that he might never write another book as good as Volcano, and he was right—although he continued to work on other books, he would never be published again.

The couple kicked around Europe for a year, where his drinking bouts took a darker turn—he nearly strangled Margerie in France. They returned to Dollarton in 1949, where Lowry briefly sobered up and cowrote a screenplay for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night. MGM was interested, but the film was never produced. They left Dollarton for good in 1954, eventually settling in Sussex, England, where Lowry received treatment for his alcoholism. Margerie had to be treated for nervous exhaustion and was chronically unhappy.

Death would claim Lowry on June 26, 1957, under mysterious circumstances. His wife found his body upstairs in the cottage they were renting in the village of Ripe, and an autopsy revealed alcohol and barbiturates in his system. The coroner stated the official cause of death as “misadventure”—an accident.

The White Cottage in Ripe.

Those close to Lowry believed that suicide was out of the question. In 2004, Gordon Bowker, writing in the Times Literary Supplement, suggested that Margerie, after enduring years of Lowry’s boorish behavior, may have played a role in his death. She had long been in the habit of plying him with vitamins to alleviate his hangovers. It would have been easy, Bowker asserted, for her to administer a fatal dose of drugs, instead of vitamins, to the unsuspecting writer.

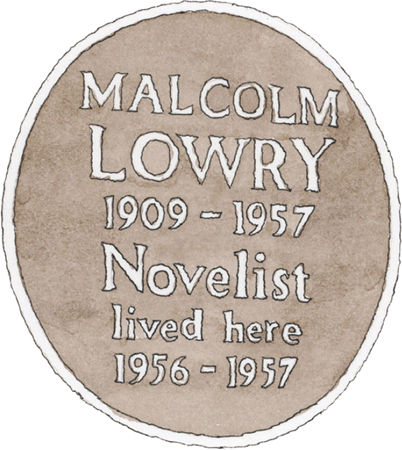

Lowry’s epitaph, which he wrote for himself, read:

Malcolm Lowry

Late of the Bowery

His prose was flowery

And often glowery

He lived, nightly, and drank, daily,

And died playing the ukulele.

Reflecting on his own excesses, Lowry also once wrote, “The agonies of the drunkard find their most accurate poetic analogue in the agonies of the mystic who has abused his powers.”

Commemorative plaque on the White Cottage.

TEQUILA VERSUS MEZCAL

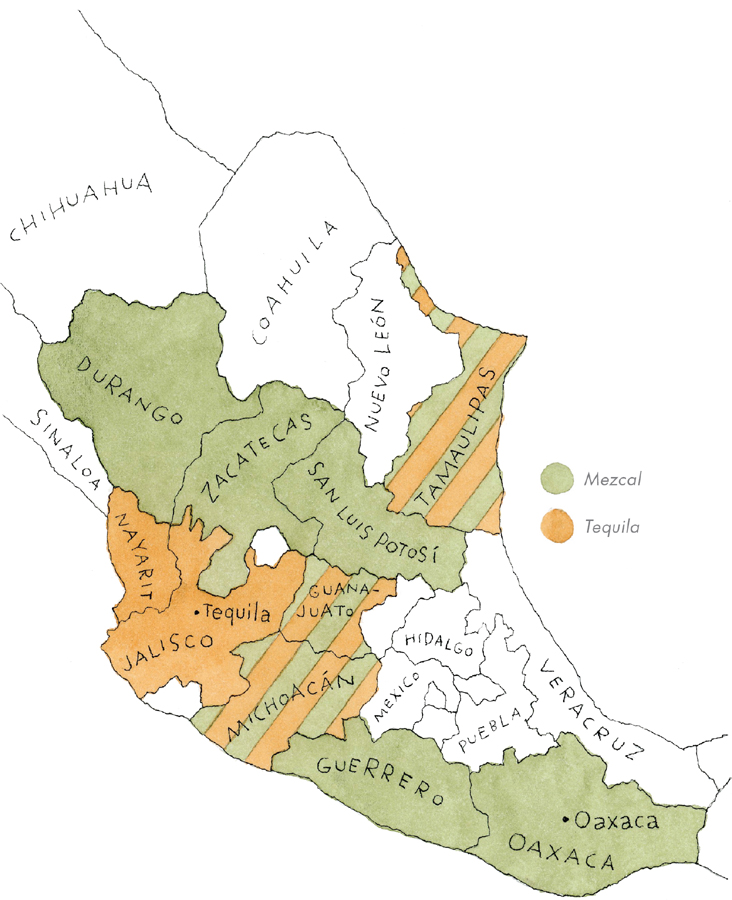

The word mezcal comes from the Nahuatl (the Aztec language) mexcalli, which means “oven-cooked agave.” Mezcal is any agave-based liquor. Tequila is a type of mezcal, in the same way that scotch and bourbon are types of whiskey. Tequila must be made from blue agave, while mezcal can be made from more than thirty different varieties of agave, or maguey.

Tequila is produced in five different regions of Mexico, but primarily in a specific area surrounding the city of Tequila in the state of Jalisco. Mezcal is produced in nine areas of Mexico, with much of it being made in the state of Oaxaca. Mescal de tequila was the first mezcal to be codified and recognized by its geographic origin and the only one recognized internationally by its own name. Both spirits are made from the harvested core of the agave plant, or the piña, but they are distilled differently. Modern tequila is most often produced by slowly steaming the agave and then distilling it several times in copper pots.

A jimador harvests agave plants using his primary tool of the trade—a coa de jima (harvesting hoe). The piña, or heart of the plant, is used for production of mezcal and tequila.

Today’s artisanal mezcal is made using traditional methods—the agave is wild-fermented in open vats and distilled in clay pots after being charred in underground pits. These pits are lined with lava rock and filled with wood and charcoal, imparting the distinctive smokiness for which mezcal is known.

Ron Cooper, the Southern California artist and mezcal importer credited with helping to boost mezcal’s resurgence, describes the difference between steaming and charring this way: “In tequila, it’s like starting with a boiled onion . . . in mezcal, it’s like starting with a roasted, caramelized onion.”

The esteemed Mexican writer and journalist Elena Poniatowska, when asked in a 2015 interview whether she preferred tequila or mezcal, replied, “Tequila. I’m from the old guard.”

Mezcal and Tequila regions of Mexico.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

Tequila had a brief, if sordid, association with the Beat Generation. Two of the literary movement’s most iconic figures, Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs, spent considerable time south of the border. Kerouac, who once said, “Don’t drink to get drunk, drink to enjoy life,” enjoyed margaritas. Burroughs often drank tequila as an exotic alternate to his usual vodka and Coke.

William “William Tell” Burroughs.

In 1951, Burroughs and his common-law wife, poet Joan Vollmer, were living in Mexico City, where they had gotten into the habit of drinking cheap tequila throughout the day. On September 6, during a night of heavy drinking with friends, a plastered Burroughs brandished a handgun and declared to his wife, “It’s time for our William Tell act.” Vollmer, laughing, placed a glass of gin on top of her head. Before anyone could raise an objection, Burroughs took aim and fired, striking her in the forehead. Her death, ruled an accident, would haunt the writer for the rest of his life.

Joan Vollmer.

THE MARGARITA

Kerouac was likely introduced to the margarita during his 1952 bus trip from the Arizona border to Mexico City, and he would return to Mexico a half dozen times in the fifties and sixties. He told Allen Ginsberg that sitting along the coast in Mazatlán “was one of the great mystic rippling moments of my life.”

Jack Kerouac.

Prior to the 1940s, few people outside of Mexico had ever heard of tequila. One of P. G. Wodehouse’s characters once ordered “a shot of that Mexican drink they call—no, I’ve forgotten the name, but it lifts the top of your head off.” The margarita would change all that.

Nobody knows for certain who invented the cocktail, but innumerable tales abound placing its origins anywhere from Acapulco, Tijuana, Ensenada, or Juárez in Mexico, to Galveston or San Diego in the United States. One popular legend maintains that it was created by Mexican restaurant owner Carlos (Danny) Herrera in 1938, for a Ziegfeld Follies showgirl named Marjorie King. She was allergic to all forms of alcohol except tequila but couldn’t drink the spirit straight. To make it more palatable, Herrera added salt and lime.

Hollywood starlet Marjorie King on the cover of a vintage French tabloid magazine.

Cocktail historian David Wondrich believes the margarita evolved from a cocktail called the daisy—a popular drink in the 1930s and ’40s involving gin or whiskey, citrus juice, and grenadine served over shaved ice. The original tequila daisy included orange liqueur, lime juice, and a splash of soda. The first stateside mention of a “tequila Daisy” appeared in the weekly Iowa newspaper the Moville Mail in 1936, by editor James Graham, who was recounting a visit to Mexico. The first appearance in print of a recipe for a drink called a “Margarita” appeared in a December 1953 issue of Esquire. The ever-popular frozen, or blended, margarita (anathema to purists!) owes its existence to the popular kitchen appliance used in the 1950s—the Waring blender.

The Classic (Unblended) Margarita

Ice

1 ounce Cointreau, triple sec, or other orange liqueur

2 ounces Blanco tequila

¾ ounce freshly squeezed lime juice

Kosher salt around the glass rim (optional)

Lime wedge for garnish

Add the ingredients to a shaker filled with ice and shake. Strain into a chilled cocktail glass filled with fresh ice and with salt (if using) around the rim. Garnish with a lime wedge.

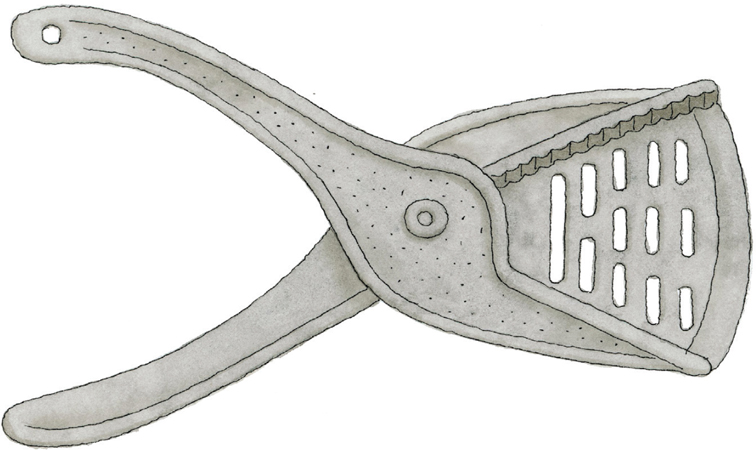

Vintage cast aluminum lime squeezer, circa 1940s.

EL BOOM

The 1960s and ’70s saw an explosion of Latin American literature known as El Boom. One of the key figures, along with Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa, was Carlos Fuentes, Mexico’s grand man of letters.

Carlos Fuentes.

In his best-known novel, The Death of Artemio Cruz (1964), he employs mezcal as a sort of cultural truth serum. Exposing the failed promise of the Mexican Revolution, the titular character, through a series of alcohol-induced flashbacks, remembers atrocities he committed as a young soldier in the name of the cause: “In the dark he felt for the bottle of mezcal. But it would not serve forgetfulness but to quicken memory. He would return to the beach and rocks while the white alcohol burned inside him. . . . Liquor was good for the exploding of lies, pretty lies.”

THE WORM

Tequila never had a worm. But certain mezcals, usually from Oaxaca, are sold con gusano (with worm). The worm in question is actually a moth larvae that feeds off the maguey plant, and its presence indicates an inferior product. The mezcal worm is believed to have been a marketing gimmick that began in the 1940s and 1950s to boost flagging mezcal sales in the wake of tequila’s growing popularity. Spurious claims of increased virility and hallucinations after swallowing the worm only added to the mystique.

A cartoon gusano rojo (“red worm”) that appears on several brands of cheap Oaxacan mezcal.

ON THE RESERVATION

Native American author Sherman Alexie, whose collection of short stories and poems War Dances (2009) won the 2010 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, often writes of the toll alcohol has taken on the indigenous American community. Raised on the Spokane Indian Reservation in the east of Washington State in a family rife with alcoholics, he fell into the same pattern and as a college student was often drinking a fifth of tequila a day.

Sherman Alexie.

In a 2009 interview with Big Think, Alexie responded to a question about whether alcohol helps or hurts writers: “So there’s certainly a lot to be said for my desperate years . . . my active alcoholic years as being the source of some pretty good work, for being the source of the two books that established and made my career. But the thing is, it’s unsustainable. . . . If you are using substances to fuel your creativity, you’re going to have a very, very short artistic life.”

He stopped drinking at twenty-three.

GRINGOS ON THE BORDER

Sam Shepard didn’t write paeans to tequila, but he, along with his characters, was known to enjoy it. A bottle of the stuff is a constant companion for Eddie, the cowboy protagonist with a drinking problem in his 1983 play Fool for Love.

Sam Shepard.

Cormac McCarthy drops mezcal into his punctuation-averse prose throughout his borderland novels.

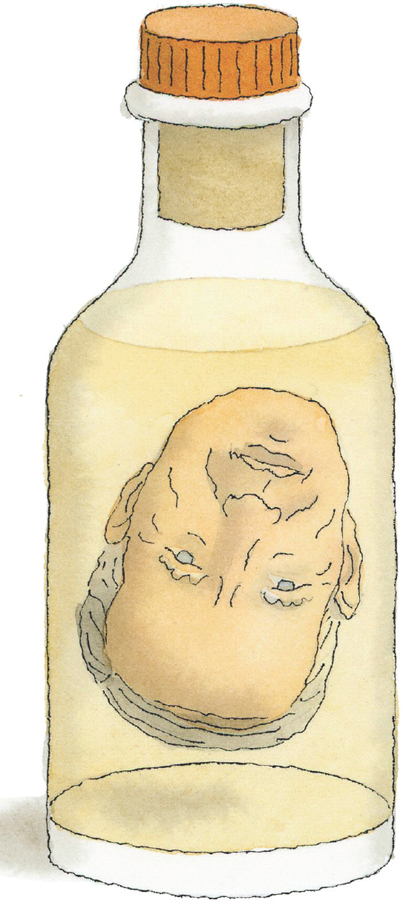

In Blood Meridian (1985) a man’s severed head is publicly displayed in a Mexican plaza floating in “a glass carboy of clear mescal.” The young cowboys of All the Pretty Horses (1992) share many bottles of the spirit. In one scene a Mexican police captain tells a story: “I was with these boys and they have some mescal and everything—you know what is mescal?—and there was this woman and all these boys is go out to this woman and they is have this woman.”

Cormac McCarthy.

In The Crossing (1994), the protagonist Billy Parham refuses to drink mezcal: “You want to drink that stinkin catpiss in favor of good american whiskey . . . you be my guest.”

SALT AND LIMEY

Today, agave-based liquors are riding an unprecedented wave of popularity—trendy bars and fine liquor stores offer an array of small-batch sipping tequilas and terroir-driven mezcals, aged to varying degrees of complexity and refinement. Just as sushi’s growing popularity triggered the overfishing of bluefin tuna, today’s mezcal boom threatens to overharvest rare, wild agave varieties.

To see how far this drink has come since its humble beginnings as a cheap corrosive for the impolite, one has only to read Kingsley Amis’s notes on tequila in Every Day Drinking, published in 1983: “Unlike other spirits, it’s never advisedly drunk on its own,” he wrote, before describing the conventional mode of consumption known to Spring-breakers everywhere: salt on the back of the left hand, lime in the right, shot glass of neat tequila at the ready.