There’s nought, no doubt, so much the spirit calms, as rum and true religion.

—Lord Byron, Don Juan (1819)

No spirit has seen its stock rise and fall with the frequency of rum, a drink whose reputation has alternated over the centuries and decades between cheap rotgut and elegant elixir, eventually culminating in its status as a magical mixer in the twentieth century.

Sacchaurum officinarum, or sugarcane.

American colonists couldn’t get enough of it—until they decided they liked whiskey more. Rum was also all the rage at the beginning of Prohibition—until thin profit margins on the cheap spirit sent bootleggers to Canada for whiskey instead. In 1934 the resilient spirit would experience another resurrection with the opening of the Hollywood restaurant Don the Beachcomber. Its Polynesian-inspired cocktail lounge, featuring rum-based tropical drinks, would introduce Tiki culture to America. The post–World War II fascination with the South Pacific helped fuel a craze that would reach its apex in the 1960s. In the intervening years Tiki’s popularity has waxed and waned, with revivals in the mid-1990s and again today.

Cane knife used by plantation slaves.

Yet despite sporadic periods of peak popularity, rum has always played second fiddle to the hard liquor triumvirate of whiskey, gin, and vodka. This is reflected in its relatively inconsequential impact on literary drinking culture.

FROM IGNOMINIOUS BEGINNINGS TO THE SEA DOG’S HAPPY DRINK

When European colonists began arriving in the Caribbean with their muskets and stills, the raw ingredients for whiskey, wine, and beer weren’t readily available. It was only a matter of time before Old World distillation techniques would be pressed into service, making use of the region’s plentiful local crop—sugarcane.

Plantation slave.

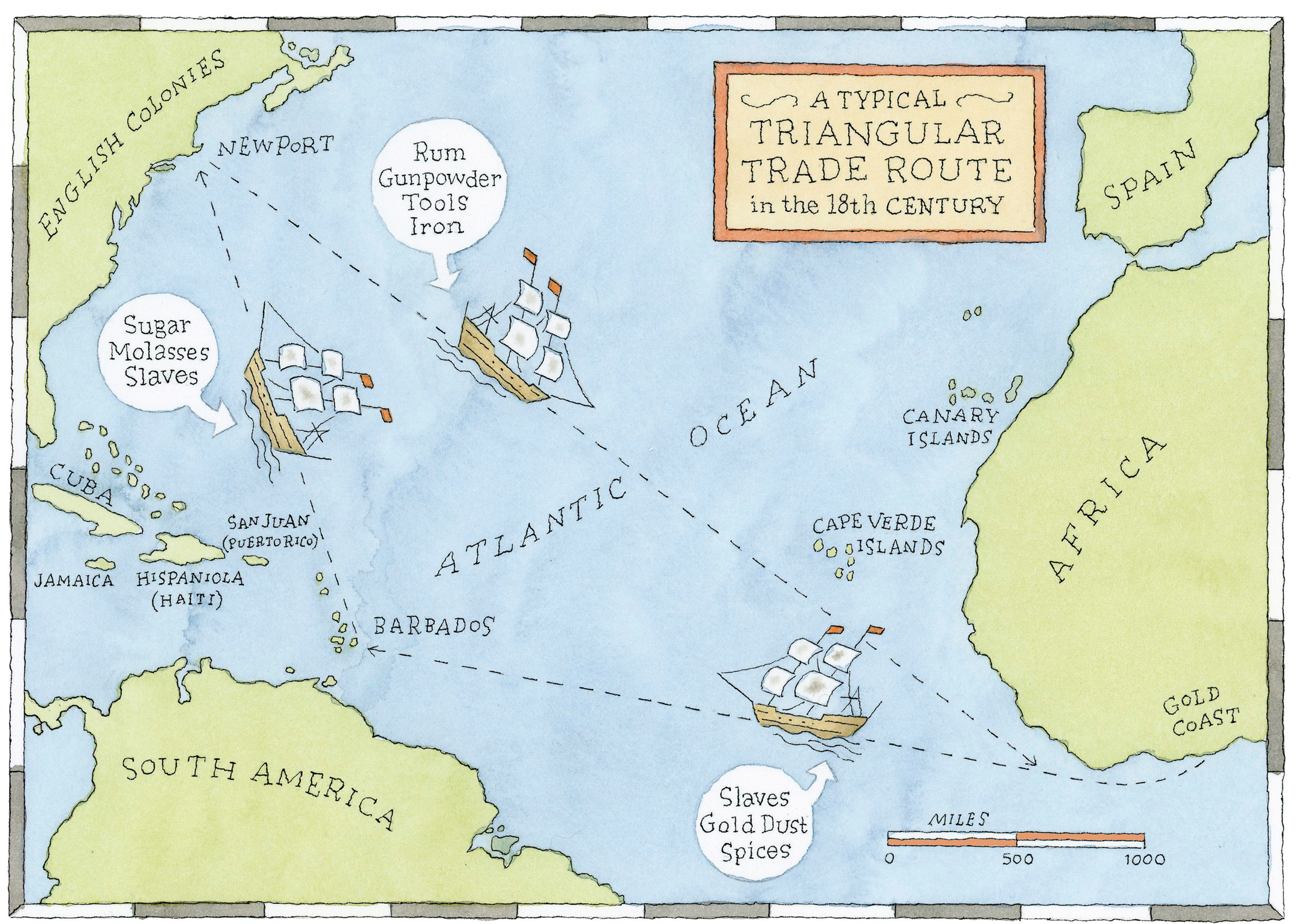

Rum production played a central role in the Atlantic triangular slave trade from the late sixteenth to early nineteenth centuries. The drink, along with slaves, molasses, and manufactured goods, was traded between West Africa, the Caribbean, the American colonies, and Europe. This accounts for the rum’s historical association with the seafaring life. Due to its wide availability, sailors and pirates operating in the Caribbean made rum their default drink of choice.

West Indies sugar baron.

The etymology of the word rum is unclear, but the first distillations of fermented molasses probably took place on the sugar plantations of Barbados, a small island in the Lesser Antilles. Prior to the discovery that molasses, a byproduct of the sugar refining process, could be fermented to generate alcohol, the sticky substance was considered a waste product and a disposal headache. As rum production ramped up, molasses soon became liquid gold.

YO-HO-HO, AND A BOTTLE OF RUM!

The writer most influential in establishing the classic iconography of pirate culture, and its association with rum, was Robert Louis Stevenson.

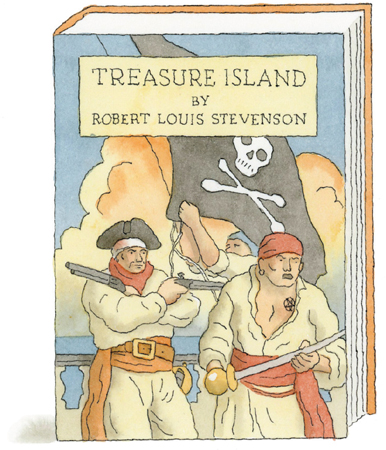

His adventure novel Treasure Island (1883) had it all: treasure maps marked with an X, chests filled with loot, skull and crossbones flags, one-legged seamen with parrots perched on their shoulders, and castaways on deserted islands. And the word rum is mentioned more than seventy times. A 1911 edition of the novel featuring the illustrations of N. C. Wyeth further cemented Stevenson’s vision in the public imagination and became the iconic Treasure Island read by generations of readers.

The 1911 edition with N. C. Wyeth’s cover illustration, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York.

In Stevenson’s time, rum was considered a crude form of alcohol (unlike the elegant wines drunk by the captain’s men—and Stevenson himself). Rum is emblematic of the recklessness, self-destruction, and violence embodied by his pirates. Early on in Treasure Island, the ailing buccaneer Bill Bones implores the young protagonist, Jim, to fetch him “a noggin of rum” against the doctor’s orders:

“Doctors is all swabs,” he said; “and that doctor there, why what do he know about seafaring men? . . . I lived on rum, I tell you. It’s been meat and drink, and man and wife, to me; and if I’m not to have my rum now I’m a poor old hulk on a lee shore, my blood’ll be on you, Jim, and that Doctor swab.”

GROG SAVES LIVES

Grog, the archetypal drink of seafarers—and a forerunner of the modern daiquiri—was the 1740 creation of Admiral Edward Vernon of the British Royal Navy. It was essentially rum drink diluted with lime juice, and served as a safeguard against scurvy, the leading cause of naval death between 1500 and 1800. Grog provided the added benefit of keeping sailors hydrated in the absence of potable water. The name came from the admiral’s nickname—“Old Grog,” on account of the heavy weatherproof cloak he wore made from grogram, a silk, mohair, and wool material.

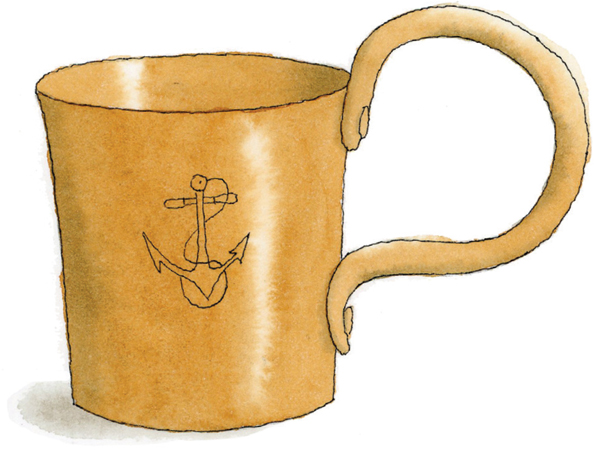

Eighteenth-century Royal Navy “½ gill” copper measuring cup—four cupfuls equaled a half pint, one sailor’s daily rum ration.

RUM AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

By the early eighteenth century, the New England colonies were awash in rum—the settlers were now distilling it themselves. Man, women, and children were drinking an average of three gallons of rum each year.

Unhappy with trade that was cutting into their own profits, the British enacted the so-called Sugar Act of 1764, effectively taxing any molasses imported from non-British colonies, and thereby disrupting New England’s booming rum economy. This measure would only serve to inflame revolutionary passions.

TROPIC THUNDER

American writer Hart Crane was a Prohibition-era modernist poet with a taste for mai tai cocktails. He was the son of a wealthy Cleveland candy manufacturer—the inventor of Life Savers—an irony not lost on those familiar with the circumstances of the poet’s death at age thirty-three.

Hart Crane.

Crane dropped out of high school at seventeen and persuaded his parents to send him to New York City, ostensibly to prepare for admission to Columbia University. Instead, he headed to Greenwich Village to make a name for himself as a poet. Ever ambitious, he proclaimed that he would “really without a doubt be one of the foremost poets in America.”

Despite his overbearing father’s nagging exhortations to get a real job, he managed to get published in several prestigious literary magazines, including The Little Review (best known for the serialization of James Joyce’s Ulysses).

The Brooklyn Bridge inspired his collection of poetry The Bridge (1930).

Like many twentieth-century American poets, he spent a good deal of time drinking rather than writing, although he was also known to combine the two pursuits. By some accounts, he preferred to write while drunk, believing it facilitated access to the mood necessary for channeling his singular, if Delphic, vision. His inability to hold down a job for any sustained period had him shuttling back and forth between Cleveland and Manhattan for much of his late teens and early twenties.

Crane’s love life was a blur of brief, often anonymous sexual encounters, mostly with men. He associated his homosexuality with his calling as a poet, using the alienation he felt, even from friends, to fuel his writing. A brief but intense relationship with a Danish sailor, Emil Opffer, inspired his poem “Voyages,” written in 1924, about the redemptive power of love.

Crane was both a contributor and an ad salesman for this literary publication.

The poet’s love of the Caribbean—and rum—can be traced to 1926, when he relocated briefly to Cuba. His evocative poem “O Carib Isle!” invokes crabs, doubloons, terrapins, and hurricanes. In a 1927 letter to his friend Yvor Winters, American poet and literary critic, he wrote, “Rum has a strange power over me, it makes me feel quite innocent—or rather, guiltless.”

Mai tai cocktail.

His parents owned a vacation cottage on the Isle of Pines, off the Cuban coast, where he wrote most of the lyrical poems for a forthcoming volume called The Bridge. In a line from the book’s poem “Cutty Sark,” Crane invokes rum as a salve for loss:

Murmurs of Leviathan he spoke,

And rum was Plato in our heads . . .

In 1929 Crane left for Paris, where his emotional baggage and drunken antics followed him. He was arrested at Le Cafe Select after a physical altercation with waiters over his bar tab. He soon returned to America and completed The Bridge.

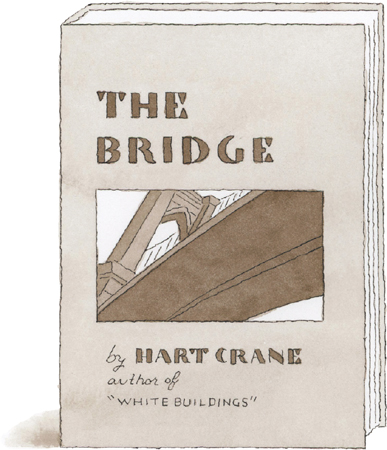

Publication of The Bridge in 1930 brought him a measure of notoriety and fame, along with some harsh critical notices. Particularly vexing for Crane were the disparaging reviews from two of his closest friends: Winters and Allen Tate (who would become the US poet laureate in 1943). This only exacerbated Crane’s growing sense of himself as a failure. Along with alternating bouts of depression and elation, his drinking worsened.

First edition, published by Horace Liveright, New York, 1930.

The Bridge would eventually be regarded by many as his crowning achievement and the greatest literary work inspired by the Brooklyn Bridge. Years later, esteemed literary critic Harold Bloom would place Crane in his pantheon of the best modernist American poets of the twentieth century. He placed The Bridge on equal footing with Eliot’s The Waste Land, even regarding Crane as the superior poet.

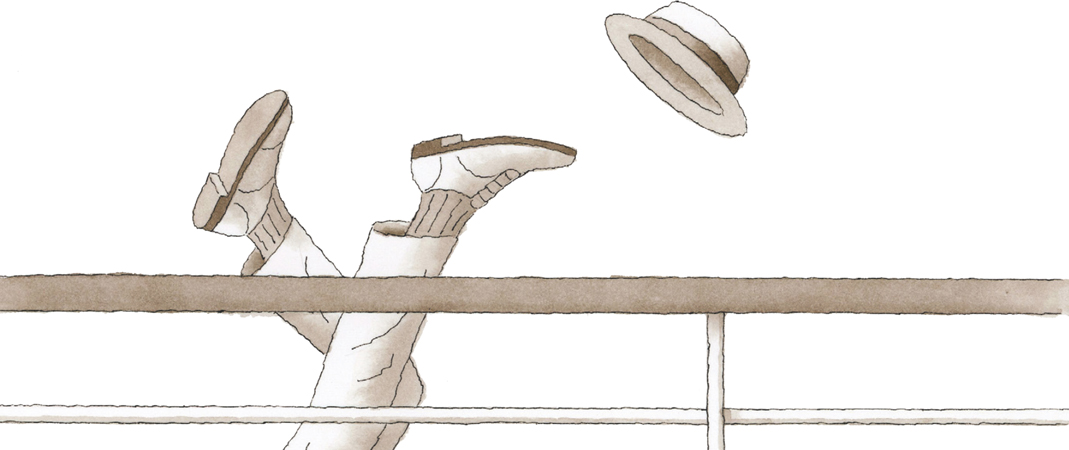

On April 22, 1932, Crane jumped over the railing of the steamship Orizaba, en route from Veracruz, Mexico, to New York, in an apparent suicide. His body was never recovered.

THE DIVA OF STEEPLETOP

In 1918, Edna St. Vincent Millay was the literary “it” girl. Her celebrity transcended literary circles—she was the Madonna of her time, flouting convention and unafraid to push the boundaries of propriety. She would become the twentieth-century archetype for the artist undone by celebrity—a cautionary tale on the fleeting nature of fame and its often destructive consequences. In her day she was said to be the second-most quoted poet after William Shakespeare. Like many writers of her day, she drank all types of liquor, but her favorite cocktail was said to be a rum-based sidecar known as between the sheets.

Edna St. Vincent Millay.

At age nineteen, Millay was encouraged by her mother to enter a competition sponsored by The Lyric Year, an annual volume of poetry. Millay’s poem “Renascence,” widely considered the best submission, was not awarded the top prize. The ensuing controversy made her a teenage cause célèbre.

A vintage Vassar College pennant, circa 1920s.

While making her mark at Vassar College, Millay would sneak away from her dorm to visit Manhattan speakeasies, establishing a reputation for her drinking prowess. She was soon invited to recite her poems at literary salons around the city.

Bearing witness was Louis Unter-meyer, an established American poet and critic, who remembered, “There was no other voice like hers in America. It was the sound of the ax on fresh wood.” Millay graduated in 1917 with a bachelor of arts degree and moved to Greenwich Village, the center of postwar New York’s burgeoning bohemian scene. That same year she published her first volume of poetry, Renascence and Other Poems.

First edition, published by Frank Shay, New York, 1922.

A Few Figs from Thistles (1920) was her breakout success, taking her celebrity status to new heights. The book was considered controversial for its progressive feminist leanings. It contains “First Fig,” one of her most famous, and prescient, poems. The short verse embodies the “live fast, die young” ethos that would epitomize the Roaring Twenties:

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

The public adored her, and her readings were cultural events. Befitting a poet-diva of the Jazz Age, she was an omnivorous drinker, a smoker, and a sexual adventurer, taking both male and female lovers. During extended reading tours across the Atlantic, she hobnobbed with Constantin Brancusi and Man Ray in Paris.

As her popularity continued to surge, she won the Pulitzer Prize in 1923 for her fourth book, The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver.

Among her many suitors was noted American critic, journalist, and fellow rum enthusiast Edmund Wilson, who once compiled a list of 104 terms for “drunk” in his “Lexicon of Prohibition” (1927). Wilson once proposed to her, but Millay, fearing a dreary life of domesticity with him, declined.

But Millay was, as Wilson put it, growing “tired of breaking hearts and spreading havoc.” She married Eugen Boissevain, a Dutch businessman, in 1923. He was a doting husband who, in a role reversal for the period, gave up his career to help manage hers. He was unthreatened by her progressive views and apparently willing to look the other way during her numerous extramarital peccadillos.

Millay lived at 75½ Bedford Street, New York City’s narrowest house, from 1923–24.

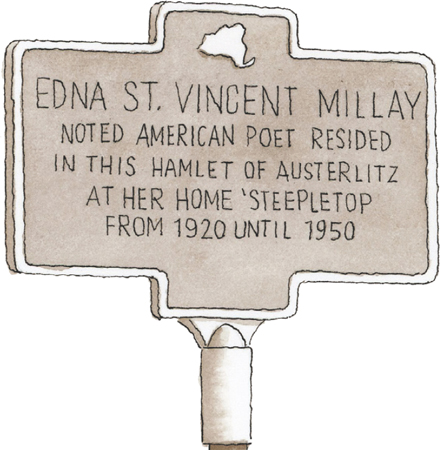

Seeking refuge from the chaos of living in Manhattan, the couple bought a country home, christened “Steepletop,” in upstate New York near the town of Austerlitz. There they hosted legendary parties. The grounds included an outdoor bar called “the Ruins,” a spring-fed swimming pool for skinny-dipping, and a badminton court. Millay would live here for the rest of her life.

Steepletop.

She continued to write, but by the early 1930s, the fire was starting to dim. Her work was becoming less personal and more socially conscious. Critics were growing less receptive, and her physical beauty (a key driver of her success) was on the decline. In 1936, following a car accident that left her in severe pain, she became addicted to morphine and increasingly reliant on alcohol and other drugs.

Historical marker on Route 9 in Austerlitz, New York.

Millay withdrew from friends and the public. As she became increasingly helpless in the face of her addictions, Boissevain was also her enabler, procuring drugs and alcohol upon request.

Eugen Boissevain.

Among the artifacts in the Millay collection at the Library of Congress are itemized monthly statements from two pharmacies in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, between 1940 and 1945. These include cases of Fleischmann’s gin, Taylor’s vermouth, Teacher’s Scotch, and Berry’s rum, as well as Demerol, Nembutal, Benzedrine, and codeine. As both the quantity and quality of her writing faded, along with her fame, Millay was eventually able to ease up on the drug use but not the booze.

A commemorative stamp, issued in 1981, honoring Millay.

When her husband died suddenly of lung cancer in 1949, a grief-stricken Millay retreated from public life, seldom venturing away from Steepletop. In widowhood she became even more dependent on alcohol to get through her days.

On the morning of October 18, 1950, Millay’s crumpled body, still in nightgown and slippers, was discovered at the bottom of her staircase with a broken neck after an apparent fall. She had likely been working and drinking late into the previous night. She was fifty-eight.

In her notebook, at the time of her death, she had circled in pencil the last three lines of a new poem she had just written:

I will control myself, or go inside.

I will not flaw perfection with my grief.

Handsome, this day: no matter who has died.

BETWEEN THE SHEETS

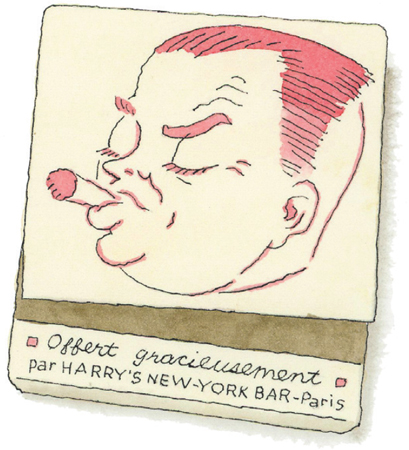

Invented during Prohibition, the between the sheets is a rum-laced variation on the classic sidecar cocktail. Its creation is usually credited to Harry MacElhone of Harry’s New York Bar in Paris in the early 1930s. It’s a credible assertion considering MacElhone’s penchant at the time for creating provocatively named cocktails—he was also responsible for a drink called the monkey gland.

Vintage Harry’s New-York Bar matchbook cover featuring Harry MacElhone’s caricature.

However, cocktail mythmakers often prefer a tantalizing story to the truth: a persistent rumor was that the drink’s name was coined by Edna St. Vincent Millay after some late-night drunken mischief involving Edmund Wilson and poet John Peale Bishop. True or not, many sources concur that the cocktail was among her favorites.

Between the Sheets

1 ounce light rum

1 ounce Cointreau

½ ounce lemon juice

1 ounce Cognac

Cracked ice

Lemon twist for garnish

Shake ingredients well with cracked ice, then strain into a chilled cocktail glass and garnish with the twist of lemon.

PROHIBITION RUMRUNNERS AND CUBA

Rum smuggling has a long and colorful history dating back to the sixteenth century when pirates, evading British ships, were running the stuff from the Caribbean to the heavily taxed American colonies. The term rumrunning would not enter the popular lexicon until the beginning of Prohibition.

Prohibition-era rumrunner.

The risk/reward ratio was high for Prohibition smugglers. To avoid coast guard patrols, captains would run without lights at night, often through dense fog. It was not uncommon for a rumrunner to sink after hitting a sandbar or a reef, often littering a nearby shore with hundreds of rum bottles.

For Prohibition-era East Coasters, pre-Castro Cuba was a rum mecca. In 1926, to entice thirsty neighbors from the north, the Bacardi company, based in Cuba, created ad campaigns—cosponsored by Pan Am airlines—exhorting Americans to “leave the dry lands behind.” Between 1916 and 1926, American travel to Cuba doubled from roughly 45,000 to 90,000 tourists a year. Havana quickly became a playground for the rich and famous, and soon a favorite destination of Ernest Hemingway.

Uncle Sam being flown from Florida to Cuba by the iconic Bacardi bat from a vintage 1920s Prohibition era ad.

PAPA DOBLE

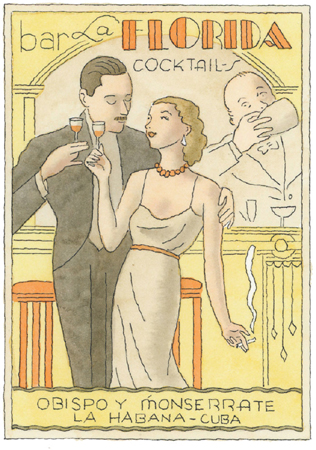

Ernest Hemingway’s abiding reverence for alcohol across the entire spectrum of spirits is unrivaled. But in the public imagination, the cocktail most closely identified with him is the daiquiri. After a morning workout pummeling the keys of his typewriter, Hemingway would escape the encroaching Havana heat by walking the ten minutes between his room at the Hotel Ambos Mundos to Bar La Florida (affectionately referred to by its diminutive, El Floridita), the famous Cuban watering hole.

A Bar La Florida 1934 cocktail menu.

According to the writer’s niece, Hilary Hemingway, it all began in the early 1930s with a fateful call of nature. In an interview with NPR, she describes how he “went into the Floridita to use the restroom one day. People in the bar were bragging about the daiquiris that were being served there. So he ordered one and took a sip. Ernest asked for another one, this time with ‘less sugar and more rum.’ And that’s how the Papa Doble, or the Hemingway daiquiri, was born.” The bartender, Constantino Ribalaigua, named the modified drink in Hemingway’s honor. Hemingway would become a fixture at the bar after moving to Cuba in 1932.

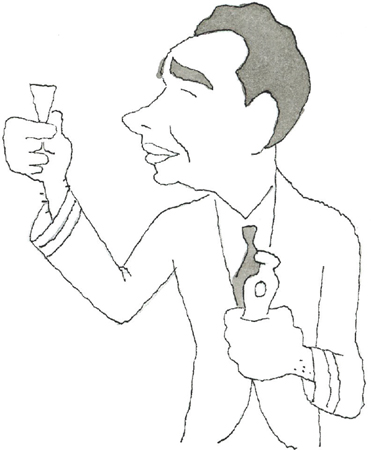

Constantino Ribalaigua as depicted in his 1939 cocktail menu.

In a letter to his third wife, Martha Gellhorn, in 1943, he wrote from Havana: “Everything is lovely here at the Nacional and the only thing lacking is you dear if you could only see the view from my room looking out over the beautiful gulf stream and Oh those daiquiris that nobody makes like old Constantino.”

The Bacardi rum logo, circa 1900.

Hemingway once boasted of knocking back seventeen of Constantino’s daiquiris over the course of an afternoon in 1942.

Papa Doble (the Hemingway Daiquiri)

Ice

2 ounces light rum (Hemingway probably drank Bacardi)

½ ounce freshly squeezed grapefruit juice

½ ounce freshly squeezed lime juice

¼ ounce maraschino liqueur

Fill a cocktail shaker halfway with ice. Add the rum, juices, and maraschino liqueur. Shake vigorously for at least 30 seconds, then strain into a chilled cocktail glass.

The daiquiri is only one of many iconic rum cocktails that enjoy popularity today, along with the mojito, the piña colada, the cuba libre, and the high-octane zombie.

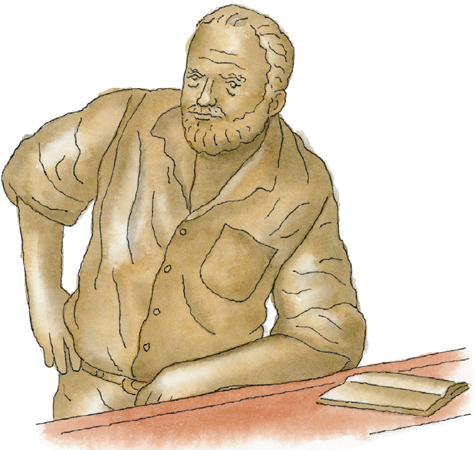

The life-sized bronze statue of Hemingway installed at the end of El Floridita’s bar in 2003, sculpted by Cuban artist José Villa Soberón.

YOUNG AND COMPLEX

Rum will never have the cachet, or price tag, of a fine whiskey, tequila, or red wine, because the spirit’s aging process doesn’t generally exceed more than a year of barrel mellowing. True to its lawless reputation, rum’s provenance and production methods are largely unregulated and, as a result, quality can be all over the map.

Yet the best expressions of the sugarcane distillate can be as complex and rewarding as a fine single-malt scotch. Hemingway also enjoyed the spirit neat (as he did most of his brown liquors). In the first chapter of A Moveable Feast, he orders himself a Saint James rum at his local café, “feeling the good Martinique rum warm me all through my body and my spirit.”