Albin Johnson, as seen in his wanted photo. Researcher Dick Lindgren speculates that Albin made his way to “parts unknown.” Pinkerton Consulting & Investigations, Inc.

12

What Really Happened?

Assuming Johnson was guilty, what could possibly have driven a man to kill his wife and seven young children? Perhaps it was Albin’s mind-set that he could no longer support his family—and that without Albin’s support, the family was better off dead. Or as the Chisago County Press put it in an April 20, 1933 article, “It appears like another case wherein a despondent person, discouraged with life, tries the worst to make things better.” It’s not unusual for despondent folks to take out their frustrations on family members. But more often than not, the killer turns the gun on himself after doing in his kinfolk. That doesn’t appear to be the case with Johnson. If Johnson did make a run for it after committing the crime, where would he turn? He didn’t have any money and his options were limited.

One long-shot possibility is that Johnson was a victim. Maybe he landed in hot water with some ruffians, perhaps moonshiners. He didn’t have as much as a dime in his pocket. Could it be that Johnson was in debt to some unsavory characters and they took revenge on him and his family? Perhaps they disposed of Johnson’s body in a remote location to throw the investigators off track. In his 1936 affidavit, Harry A. Galpin hints at the possibility of third-party involvement. If the “unexplained bones found by relatives in a distant part of the ruins” weren’t Albin’s, perhaps it was proof that “an accomplice might have been detected,” Galpin wrote. Still, there’s little proof to back up those claims.

The more conventional view is that Johnson just slipped away. Lindgren said it would have been easy in Albin Johnson’s day to hide in plain sight. Law enforcement was pretty unsophisticated. Hobos, wanderers and highwaymen could easily blend into the crowd. Another factor: There was plenty of lawless activity at the time. The infamous Bonnie and Clyde were at the height of their notoriety. Perhaps law enforcement, such as it was, had more to worry about than a fugitive farmer from the heartland. “I imagine law enforcement had much bigger fish to fry,” Lindgren said. “Law enforcement was completely overwhelmed by what was going on.” As Lindgren put it, there were “millions of people riding the rails” in those days, desperately looking for work in the dark days of the Depression. “He could have been in Montana before they thought to look for him,” he said. Moreover, the searchers wouldn’t make anyone forget about Sherlock Holmes. At the time, the county sheriff ’s department was “an absolute joke,” Lindgren said. “The only requirement to be a sheriff was to be big and tough.”

“My personal opinion is Albin crossed the river into Wisconsin, and could have gotten help from his brothers, or hopped a freight or thumbed a ride to Duluth/Superior and went to parts unknown,” Lindgren said. “But I guess we will never know what happened. Too bad they can’t dig up the graves and do DNA and see if any parts of him are there. Never happen though.”

Another longtime area resident, Greg Strom, speculates that Johnson likely would have taken his wife and seven children out of the house one at a time. There, he could have strangled each member of the family before placing their bodies back inside the house in their sleeping positions. “Obviously they had an outhouse. Maybe he woke up one kid at a time, [and said], ‘Let’s go out to the outhouse.’…They wouldn’t have died perfectly still like they went to bed,” Strom said.

Albin Johnson, as seen in his wanted photo. Researcher Dick Lindgren speculates that Albin made his way to “parts unknown.” Pinkerton Consulting & Investigations, Inc.

Other old-timers are inclined to believe that Albin Johnson was innocent.

Muriel Kennedy Krantz Cash isn’t related to the Johnson or Lundeen families. But geographically speaking, she was as close as anyone to the fire. As a child, she lived on the farm next to the Johnson place. Her father, Ragnar Krantz, discovered the fire and then alerted the Rush City Fire Department. As of summer 2017, Muriel was still alive and well and living in the Harris–North Branch area. She still looks like the picture of health well into her eighties. She has longish, curly gray hair and a warm smile. Muriel sat down and talked about her family and the Johnson tragedy at the North Branch senior center, where she occasionally shows off her musical talents. On a warm day in July 2017, she was recruited at the last minute to play the piano in honor of a senior center worker who was leaving for a new job.

Muriel was only two years old when the fire happened, so she draws a blank when asked what she remembers about it. Her parents, of course, remembered it well. But they didn’t talk much about that horrific day, Muriel said. “It was too awful,” she said. “My folks were very reticent about anything. There were other things I knew that they never talked about. Not this, but in the family. Every family has some black sheep, and they didn’t talk about them either.” (To be clear, no one has ever suspected anyone named Krantz had anything to do with the fire.) Perhaps Muriel, like her parents, is simply too nice to entertain thoughts that an old neighbor was capable of such a monstrous deed. But she’s in the group that says Albin didn’t do it. So was her mother. “My mother always said that she was convinced the babies’ bones were burned up completely.…But she was always looking on the bright side of things. So she couldn’t believe that Albin would do that.”

Jeanette Johnson, Alvira’s niece, tends to believe the investigators who determined that Alvira and her children were dead before the flames consumed the house. “If they had been alive, there would have been an effort to escape the fire,” she reasons.

Even so, a surprising number of people were and are convinced that Albin was innocent. Alvira’s sister Ellen Scherer was among those on the Lundeen side of the family who gave Albin a not guilty verdict. “Albin had a sister-in-law, Mary, who was acquainted with Ellen,” Jeanette recalls. “Mary said, ‘Albin loved his family, he would never do something like that.’ She insisted. And she had Ellen convinced he didn’t do it.”

Others are skeptical of the investigators’ insistence that Alvira and the children were found in their sleeping positions—a vital clue that led to the conclusion that the victims were dead before the house went up in flames. “How can they determine that they were in their sleeping positions? When the authorities got there, there was only a corner of the house left. That whole thing would have collapsed,” a veteran of the Rush City Fire Department said at a North Chisago Historical Society meeting in 2017. “I’ve been in the fire department for thirty-one years, and I never saw that one.”

And then there was Harry Galpin, Albin’s devoted brother-in-law. Though Galpin’s scathing affidavit in defense of Johnson fails to offer concrete evidence that Albin died in the fire, Galpin did raise some serious doubts. Was there some kernel of truth in his bold assertions that the authorities and investigators were incompetent at best or corrupt at worst?

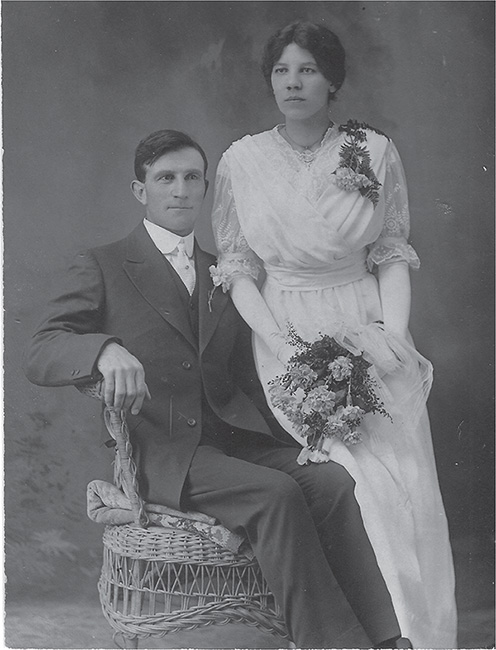

Matt Scherer and his wife, Ellen Lundeen Scherer. Ellen believed that her brother-in-law Albin Johnson was innocent. Author’s collection.

In the old days, and today in many cases, people tended to put their faith in law enforcement. County attorneys, judges, fire chiefs and medical examiners wear the white hats. They’re smart. They’re educated. And they live in the mansions up on the hill. Why shouldn’t we take them at their word when they say something is amiss with Albin Johnson? Aren’t they more credible than Johnson’s ordinary friends, neighbors and kinfolk?

Now we know better. Just look at the headlines. The officer-involved shooting of Philando Castile, for example, raised serious doubts about the actions and judgment of the accused cop. Similarly, a Minneapolis neighborhood reacted with anger and disbelief when an officer shot and killed an innocent woman, forty-year-old Justine Damond, in the summer of 2017. In 2016, a judge in Seminole County, Florida, “berated and belittled” a domestic abuse victim in the courtroom, as reported in a September 2016 Washington Post story. The judge was dressed down by the Florida Supreme Court.

Those stories are reminders that anyone can mess up. Perhaps Harry A. Galpin realized that when he dove headfirst into the Johnson case, trying desperately to clear the name of his embattled, missing brother-in-law. Maybe Galpin was ahead of his time. Or maybe he was just blinded by his own interest in standing up for the honor of his sister’s husband.

A good case can be made that the investigation into the fire and presumed murder was sloppy and incomplete, but the facts seem to indicate that Albin Johnson snapped and killed his family. The family had just been kicked off the farm, and their options were limited. It would have been quite a coincidence that the house just happened to go up in flames at precisely that moment of desperation.

As to the skepticism about the evidence that Alvira and the children were found in their sleeping positions, it should be remembered that the investigators were very clear about where the bones were found. Specifically, “remains of five of the children were found huddled near one of the doors and the mother’s body lay [beside] the crib of the baby,” the Chisago County Press reported on April 13, 1933. “Bones of another child were found in a corner of the cellar directly below where the kitchen stood.”

The Chisago County Press offers more details. “The body of the mother, Mrs. Alvira Johnson, and the tiny babe [James]…were found in a bedroom located in the southeast corner of the house. The bodies of five of the other children were found together in an adjoining room, and the body of the oldest boy [Harold] was found in the northwest corner of the kitchen,” the newspaper states.

In a 2018 interview, fire consultant Nyle Zikmund, former chief of the Spring Lake Park–Blaine–Mounds View Fire Department in suburban Minneapolis, said there’s a chance that the family members could have been rendered unconscious from carbon monoxide poisoning. But it’s more likely that the mother and seven children were lifeless before the fire started, as investigators concluded in 1933, he said. Fires are noisy, and it seems “extraordinary that everybody slept through it. That seems highly improbable,” Zikmund said. “You wake up from heat, too. Heat wakes you up, noise wakes you up. And I have never seen scientific evidence that your olfactory senses don’t work when you sleep.”

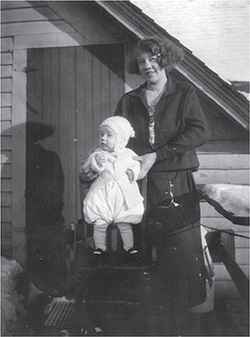

Alvira Lundeen Johnson and Harold. Alvira’s body was reportedly found in a bedroom. Harold’s remains were in the kitchen. Author’s collection.

What about the potentially incriminating evidence? Wennerberg said that “two pistols and rifle” found at the scene may have been used to slay the mother and children. Pinotti saw the kerosene can in the evidence locker. More important, of course, is what they didn’t find: any trace of big Albin Johnson, dead or alive.

Zikmund said investigators can rule a fire “suspicious” even if they don’t have enough evidence to prove arson. In this case, “you are firmly entrenched on the suspicious pedestal because you’ve got way too many unexplained and abnormal behaviors,” he said.

An old neighbor of the Johnsons’, the late Elsie Anderson, was clearly suspicious of Albin Johnson and his motives. Mrs. Anderson, who was an adult at the time of the fire, knew Albin personally. In a 1992 interview, Mrs. Anderson said she was certain that Albin Johnson had hopped a midnight train to Canada, where he had previously worked as a logger and a farmhand. Her husband, Jack, was good friends with Fred Peterson, Alvira’s brotherin-law. Elsie’s daughter, the late Mae Anderson, was similarly persuaded. Unlike today, a man in 1933 could quite easily run away and assume a new identity, she reasoned in a 1992 interview with the author. Perhaps that’s exactly what the fugitive farmer managed to do.

Good theories. But in the end, that’s all they are—theories, assumptions, conjecture and best guesses. Betty Kollas, Alvira’s niece, sums it up nicely: “There are a lot of things that could have happened. And I don’t think anybody knows for sure,” she said.