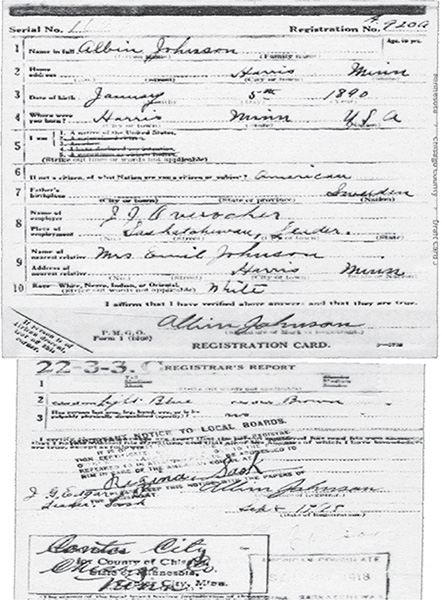

Albin Johnson’s World War I draft card. Chisago County, Registrar’s Report.

2

The Johnson Clan and the Professional Boxer

WHO WAS ALBIN JOHNSON?

Albin Johnson, the person, is almost as much of a mystery as the fire that became associated with his name. Fortunately for him, his last name lends itself to anonymity, which would come in handy in his case.

One thing we know for certain: He was a big man. Carrying his 240 pounds on a husky six-foot, three-inch frame, he was a true heavyweight, much like his brother-in-law Farmer Lodge, a professional boxer who sparred with Jack Dempsey and went toe-to-toe with world champions Jack Johnson and Primo Carnera. Born in the dead of winter on January 5, 1890, in Harris, Albin P. Johnson had light-blue eyes and sandy brown hair, according to his World War I draft card. Young Albin was by no means a scholar, but he got at least some rudimentary education as a child. In 1900, ten-year-old Albin Johnson was in school and was able to read and write, according to a U.S. Census report for that year. Years later, his future brother-in-law Harry Galpin noted in an affidavit that Albin’s formal education ended after the sixth grade.

According to the 1920 U.S. Census, Albin Johnson was living at the time with his father and mother—Emil and Cecelia Johnson—and four siblings on a farm in the Harris area. Albin was thirty years old. His occupation is listed as “laborer.” Though his mother and father came from Sweden, Albin’s native language was English, the census report notes. By all appearances, Emil and Cecelia tried to give Albin and his siblings a Christian upbringing.

Albin Johnson’s World War I draft card. Chisago County, Registrar’s Report.

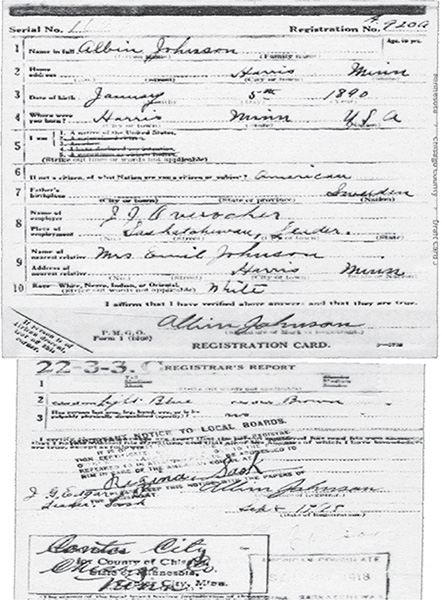

Albin’s youthful face can be seen in a 1904 confirmation class picture from the Harris Lutheran Church. Albin holds down a spot in the middle of the back row, where all the tall kids are told to stand, just a few feet away from his brother Ted. With a thick head of hair parted down the middle in the style of the day, and a stoic, serious expression befitting his Scandinavian heritage, young Albin is quite handsome. He looks like a typical teenage boy in some ways. But his piercing eyes stare back at the photographer with a serious look and a hint of sadness. His female classmates, their hair tied up with bows, occupy the front and middle rows in front of the boys. Staring at the camera with unsmiling faces and flowers pinned to their dresses, they sit primly and hold their Bibles, waiting patiently for the photographer to capture the moment for posterity. Perhaps Albin had a romantic interest in one or more of the girls—several of whom, incidentally, were named Lundeen. Or maybe he was destined from the start to become involved with another young girl named Alvira Lundeen, who was just a year old when this confirmation photo was taken.

Albin Johnson’s confirmation photo. Albin is in the middle of the back row, hair parted in the middle. Ted Johnson is in the back row, far left. First Lutheran Church, Harris.

Front and center in the photo is Pastor Linner. With thinning hair and a Bible grasped firmly in his right hand, the good reverend looks to be a man in his early to mid-thirties. He was mature enough to have some experience in the ways of the world, but not too old to have a good rapport with his young charges. Did the pastor see anything in Albin? Did he sense that young Albin may be struggling with some inner demons? Did he try to intervene in some way, perhaps take the young man under his wing? No one knows for sure.

We do know that Albin made his home in Chisago County, which was a magnet for Swedish immigrants in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Author Wilhelm Moberg chose the East Central Minnesota county as the new-world destination for the fictitious Swedish family featured in his popular Emigrants series. In the Moberg books, the main characters are Oskar and Christina Nilsson and their children. Like the Johnsons, they struggled to get by. The winters weren’t just cold. They were bitter, intimidating and even deadly in some cases. The work never ended in the farm country, and the rewards for that hard labor were often meager. It was a story of hardship, survival and endurance. The story is set in the 1840s. Not long after, Emil and Cecelia Johnson, parents of Albin Johnson, were among the real-life Swedish immigrants who settled in Chisago County.

Chisago County is tucked in between Pine and Washington Counties on the north and south and is bordered on the east by the great St. Croix River, which separates Minnesota and Wisconsin. The county’s name stems from a Chippewa Indian word. Roughly translated, Ki-Chi-Saga means “Fair and Lovely Lakes,” according to the county’s website. Established in 1851 when Minnesota was still a territory, Chisago County attracted its first European settlers around 1680 and later became an important outpost for fur trading and the logging industry.

Swedish immigrants began to settle there in the early 1850s. In A History of the Swedish-Americans of Minnesota, published in 1910, author A.E. Strand boasts that Chisago County presented “an agreeable variety” of undulating land that was “covered with hard and soft-wood timber” and “well-watered by lakes and streams.” The county’s “lake scenery is surpassed in beauty only by some of the lakes in Sweden,” the author gushes.

According to Strand, an immigrant named Oscar Roos “could claim the honor of having been, probably, the first Swedish settler not only in Chisago County, but in Minnesota.” Roos was born in Västergötland, Sweden, in 1827 and came to America in 1850. He made his way to Minnesota via Rock Island, Illinois. One of his traveling companions, Strand writes, was Lars J. Stark, “who later also settled in this county.” The name “Stark,” which means “strong” in Swedish, would soon become prominent in the investigation of the Harris fire. But that’s getting ahead of the story.

Emil Johnson was born in Älghult, Sweden, on July 1, 1862. According to his obituary in the Rush City Post Review, Johnson was “baptized, confirmed, and received his early Christian training” there. Home to only 446 residents as of the 2010 census, Älghult is in the heavily wooded southern Swedish province of Småland. The community has a strong kinship with fire. Like the Swedish town of Orrefors, Älghult is home to a glassblowing factory, where people trained in that craft create beautiful works of art with help from molten glass and fiery furnaces.

Emil Johnson may or may not have been an artist. It’s not known exactly what he did in the old country, but it’s a safe bet that he struggled to scratch out a living. At minimum, he wasn’t hopeful about his future in Sweden. Emil was only twenty years old when he ventured across the ocean to make a new life for himself in the United States. He first stepped foot in the United States in 1882, just seventeen years after the end of the U.S. Civil War and a year after President James A. Garfield was assassinated and replaced in the White House by Chester Arthur.

Emil ended up in Harris, a Chisago County farm town fifty-five miles north of the Twin Cities. He managed to buy some farmland in the new country, and he was in love. In 1888, six years after he arrived in America, he married Cecelia Blomberg, a woman three years his senior. He was twenty-six; she was twenty-nine. Cecelia’s family owned a piece of farmland next to Emil’s land. After the couple married, they merged the farms.

Cecelia Blomberg Johnson had strong ties to the local church and a desire to serve. Poor health precluded her from serving as much as she would have liked. Cecelia was sixty-four when she died on March 20, 1924. She passed away at the Bethesda Hospital in St. Paul after an illness of several weeks. “After a serious operation, [she] had recovered to the extent that it was thought she could be removed to her home in another week,” the Post Review obituary states. “Her unexpected death was a distinct shock to members of the immediate family, who were looking for a rapid recovery.” Her death notice in the Rush City Post Review also states that she was “a member of the Lutheran church at Harris and always took active part in all church affairs whenever her health permitted….She will be greatly missed by all who knew her and loved her for her ever-ready help and kind sympathy in time of need.”

Emil outlived Cecelia by twenty-four years. The Post Review described Emil at the time of his death as a man “endowed with a strong body and sturdy character” who “contributed much to the upbuilding of this community.” Emil was a charter member of the First Lutheran Church in Harris. The Swedish immigrant had a hand in constructing the building, including the majestic bell tower, which continues to produce beautiful chimes that resonate throughout the sleepy town. Some folks who knew the family described them as pillars of the local community. They were well respected and liked, according to the obituary.

Others remember a very different Emil Johnson.

Betty Kollas, a niece of Alvira Johnson, recalls that her grandmother Christine Lundeen never cared much for Emil Johnson. Betty heard rumblings through the years that Emil had an abusive streak. “You got the idea that he was very cruel to his kids,” she said. “I had the idea that Grandma and Grandpa Lundeen didn’t like him at all.”

Floyd Pinotti, a longtime Chisago County resident who acquired the old Ragnar Krantz farm near the Johnson place, is also inclined to question the actions of the elder Johnson. “I don’t want to overstate this, but I am a grandfather,” Pinotti said in a 2018 interview. “I am a grandfather and a great-grandfather, father of seven and stepfather of two. And if anybody would say I would ever evict one of my children—that would be a catastrophe….During the Depression, when a parent would evict a son from the property who had seven kids, that’s a pretty radical thing.”

First Lutheran Church, Harris, Minnesota. Emil Johnson helped build the church. Bill Klotz.

One of Pinotti’s stepsons is Steve Hansmann. Though Hansmann never personally knew Emil Johnson, he also got the impression that the old man wasn’t exactly a saint. “I always heard that the grandpa, the old man (Emil), was kind of an asshole. He was super righteous, but not a nice person. He wore his faith on his sleeve but he evicted his own grandkids for crying out loud,” Hansmann said.

For his part, Dick Lindgren doesn’t find it shocking that Emil would evict his own flesh and blood. Money was important to Emil, and the elder Johnson probably counted on the rent he got from the farm, said Lindgren, a longtime Chisago County resident who now lives in Michigan. Numerous reports indicated that Albin was behind on the rent. Albin couldn’t make good on his end of the bargain. “I think Emil said, ‘Start paying or get out,’” Lindgren speculates. “It doesn’t surprise me a bit that Emil kicked them off the place. There was absolutely no money to be had. I could see that happening, where Emil said, ‘To hell with you. It’s time to let one of the other boys give it a try.’” Given his reputation as a heavy drinker and a no-account rabble-rouser, Albin may have been his own worst enemy when it came to getting his deeply religious father’s approval. “Emil was probably a pretty strict disciplinarian. He took his religion pretty seriously. It didn’t please him to see his boys acting the way they did,” Lindgren said.

Emil Johnson was in poor health for some time near the end of his life. A month before his eighty-sixth birthday, the patriarch of the Johnson family suffered a heart attack. He died shortly thereafter at Rush City Hospital. The real Emil Johnson and the public persona of Emil may well have been two different things. Perhaps there was a dual personality within that body. That could explain, in part, why the Johnson boys had a reputation as roughnecks and hooligans. Could it be that the abused children grew up to be abusive adults?

Long before Emil and Cecelia died, they started a family that eventually included four sons and three daughters. Theodore was the eldest son, followed by Albin, Hjalmer and Henry. In later years, Theodore worked at an auto plant in Flint, Michigan. Hjalmer served with honor in World War II. The daughters were Elsa, Olga and Esther. Esther went on to marry Walter Kenneth “Farmer” Lodge, a professional boxer and wrestler. Standing six-foot-three and weighing 230 pounds, Lodge was one of the more remarkable characters to cross paths with Albin Johnson and company.

Boxing writers of the era often treated Lodge with derision. In the buildup to Lodge’s fight with Luis Firpo, 1920s-era sportswriter W.C. Vreeland ridiculed the Minnesotan as a “ham of a fighter” who was willing to “be the chopping block” for the Wild Bull of the Pampas, as Firpo was called. Lodge didn’t win any championships, and he never cracked the top ten in the heavyweight rankings. Not especially popular among the fans, he often wore the black hat to the ring in the eyes of the spectators, who cheered lustily for his much smaller, grittier opponents. But he packed a walloping punch and wowed the fans with his sheer size and strength. And no one could accuse Walter “Farmer” Lodge of backing down from a challenge. During a ring career that spanned from 1915 to 1930, a golden era of professional boxing, Lodge took on all comers. He went toe-to-toe with world champions Primo Carnera and Jack Johnson and elite contenders such as Billy Miske, Bill Brennan and Firpo. Though he lost those big fights—and won only thirteen of thirty-five professional bouts in all, according to boxrec.com—he achieved some notoriety as a favorite sparring partner of Jack Dempsey, a megastar of the 1920s and one of the greatest heavyweights ever to lace on a pair of gloves. Outside of the ring, Lodge served his country with honor in the Great War, presumably fighting the Germans with the same resolve and determination he showed in the squared circle. After the war, Lodge found love in the person of Esther Johnson.

Albin Johnson’s sister could have done a lot worse when it came to finding a husband. An undated photo of Lodge from his boxing days shows a muscular country boy standing in the orthodox boxing position. He had short-cropped hair and a clean-shaven face that looked like it was carved out of Minnesota granite. He boxed professionally out of St. Paul. It was the sport’s heyday, when the legendary Dempsey ruled the ring and big guys like Lodge couldn’t resist the urge to show off their toughness in this toughest of sports. Lodge oftentimes boxed Dempsey in exhibition matches. One such match, in Baltimore, was captured on film. The somewhat blurry, black-and-white photo of the two boxers is available in the Library of Congress archives. Lodge is the one in a horizontal position. During his fifteen-year ring career, Lodge fought all over the U.S. and in two foreign countries and scored victories over the likes of Andre Anderson, “Oklahoma Kid” Harvey, “Indian Joe” Cline and Paul Samson Koerner, according to boxrec.com. Lodge’s 1930 match with future world champ Primo Carnera, another clumsy giant of a man, didn’t go as well. The Ambling Alp dispensed of Lodge in the second round. It was Lodge’s last professional bout. The Associated Press reported that Carnera “pushed Farmer Lodge, ponderous Minnesotan, about the ring like a child and then knocked him out in the second round tonight.” The ponderous Minnesotan’s ring activities weren’t limited to boxing. When he wasn’t plowing fields or taking punches on the chin, Lodge tried his hand as a professional wrestler. In February 1934, the Minneapolis Star reported that Lodge started out as a grappler, turned to boxing and then gave wrestling another shot after “too many knockouts convinced him that the pugilistic game wasn’t what it was cut out to be.”

Farmer Lodge died on August 5, 1941, when he was only forty-seven years old. Esther Johnson Lodge preceded him in death eleven years earlier. According to his death notice in the North Branch Review, Lodge broke his ribs after a fall from a grain stack on his North Branch farm. He later developed pneumonia and went down for his final ten count at the Veterans Hospital in Minneapolis.

Though there’s no record that Albin Johnson ever boxed professionally, Betty Kollas, a niece of Alvira, has a hunch he might have tried his luck in the ring to make some extra cash. “That was one way a man could earn a few dollars, was to go into the ring with someone,” Betty said. “Albin was desperate for money. He would probably go into the ring. His personality was, ‘I could knock anybody out.’”

Indeed, all of the Johnson brothers were arguably every bit as rugged as their pugilistic brother-in-law. The boys were reputed to be rough and tough, and they were big lads, one and all. Some folks have whispered that the Johnson brothers not named Albin may have had something to do with the tragic fire. More on that theory later.

But one thing’s for sure: the Johnsons were big and powerful, and you were wise not to cross them. They didn’t mind taking a drink, often to excess, and it was rumored that they ran a moonshine operation in Wisconsin. Supposedly, Henry and Ted took turns getting drunk on Friday nights at a local bar. Just off Highway 61, about halfway between Harris and Rush City, folks still drive by a small, unremarkable structure that was frequented by the Johnson brothers. As the story goes, Albin and company walked five miles there to quench their thirst with alcoholic beverages—illicit servings, no doubt, because this was during Prohibition. It took some serious shoe leather to get there. And the return trip must have been a greater adventure as the boys staggered back home.

One of the brothers, in particular, is well-remembered by old-timers in the Harris–Rush City area. The name imprinted on his birth certificate is Henry Arthur Constant Johnson, but most folks in the area remember him simply as “Hank” or “Big Hank.” Born on May 26, 1894, in Sunrise Township, Big Hank Johnson was “baptized and confirmed at First Lutheran Church in Harris,” according to his death notice. He married his wife, Mary, in 1938. Nine years later, Hank and Mary made their home on the farm place that had belonged to his father, Emil. It was the same land that Albin had unsuccessfully attempted to farm and was forced to vacate just before the fire. Henry Johnson in particular was described as an irascible character. Some said he didn’t want any discourse with his neighbors. Others said he would do anything to stay on good terms with those who lived nearby, going as far as to put a bullet into his own dog to keep a neighbor happy.

Mark Ruhland, a Twin Cities resident, has a connection to the Johnson side of the family. His grandmother Mary Johnson was married to two of the Johnson brothers: first Ted, and then Henry. (It must have been quite the small-town scandal in the 1930s for her to leave one brother and then hook up with the other. It’s not clear exactly how the breakup played out.) Mark Ruhland said Mary Johnson was “not a logical thinker.” She had left Ted off and on while Mark’s mother, Audrey, was growing up. Audrey was still in school when she finally ditched Ted for good and fell into the arms of Big Hank.

By 1933, Emil had retired and moved to town. He turned the farm over to Albin. After the fire, the property sat vacant for a while, and then Big Hank Johnson took over the place in the late 1940s. He built a small house of his own there and settled in. “We remember when we went up there, when we were in grade school, they had a real tiny little house,” Ruhland recalled. “The house that my grandma and Hank lived in was a teeny little one-bedroom house. And then around the outside of the house there was kind of a low brick foundation. We remember playing on it.…My dad never told us what that was, but that was the foundation for the original house.”

Ruhland remembers both Ted and Henry in their later years. When Ruhland was a youngster, his family would head north from suburban Minneapolis to visit Big Hank and Mary once or twice a year. “I lived in Shakopee at that time. That was an eighty-mile drive up there. So we would go a couple of times a year. And we would also see Ted. He lived in Henderson,” Ruhland said.

Ted was a hardworking fellow who had a good job in his later years at a car plant in Flint, Michigan. But he wasn’t much of a conversationalist, at least not with the children. “Ted, he was a good-looking guy, tall and I think he had good mechanical skills, woodworking skills, stuff like that, that he learned over the years,” Ruhland recalled. “But he didn’t spend any time talking to us kids. He talked to my folks. We were just sort of cut loose and told to go outside or something. I don’t remember ever having a one-to-one conversation with him.”

Henry was different. He was kind of “coarse,” Ruhland recalled, but he played the guitar and kept the kids amused by doing all sorts of funny things, like wiggling his ears. “We called him Hank,” Ruhland said. “Hank was more of a friendly sort. He would do tricks and tell us jokes and entertain us a little bit. Let us ride on the horses. He would take us around the farm a little bit. So we liked Hank.”

That likable version of Hank was getting on in years. He was also sober. His demeanor, apparently, could turn ugly after a few too many alcoholic beverages. “I could see that if you poured eight beers into him, he could have been a nasty drunk, too,” Ruhland said.

One of the old farmers in town who was all-too-familiar with the rough-and-tumble Johnson brothers was Victor Ramberg, who had 180 acres at the bottom of the hill from the Johnson place. Like any other town, Harris had its share of colorful characters, and Ramberg certainly fit that bill. When Ramberg was well into his eighties, he inquired about purchasing some wooden posts for a fence. The fence would be exposed to the elements, so Ramberg was advised that he needed weather-treated wood to make it last. Ramberg responded, “I’m too old for that,” one old-timer recalled. “I don’t worry about treated fence posts at my age.”

Memories of Vic Ramberg put a smile on the face of another Chisago County native, Steve Hansmann. “He was a good guy—a short little Swede, with huge hands, blue eyes like Paul Newman,” recalled Hansmann, the neighbor who grew up near the old Johnson place. “Victor would visit. He gave us our first farm dog. A feral bitch he had shot was killing his chickens, and he gave us one of the pups. And he liked us. He would come out and visit,” said Hansmann, a convivial, husky man with a thick white goatee.

A World War I veteran, Ramberg took a machine gun slug in the shoulder when the bullets started flying on the battlefield at Ardennes, France. Years later, he would complain to anyone who would listen, including Hansmann, about his war wounds and the incompetent French surgeon who botched an attempt to put the pieces of his flesh back together. Hansmann was about thirteen when Ramberg pulled him over and told him all about it. “He used to tell me, he said, ‘Stevie’—he had kind of a Swedish accent—he said, ‘Come over and listen to this.’ He moved his arm like this, and you could hear it creak,” Hansmann said, making a flapping motion with his left arm. “‘You know what that is, Stevie? That’s the goddamned French surgeons who wired me up.…Those goddamned Frenchies wired me up with some baling wire.’ And it sounded like a rusty old machine.”

“He was a nice old man. I really liked him,” Hansmann added.

Ramberg had a complicated relationship with the Johnson brothers. He must have been friendly enough with Big Hank. After all, he worked the handles as a pallbearer at Henry’s funeral in 1967. But he also appeared to be taken aback by Big Hank’s temper. Having served in the Great War, Vic Ramberg was no coward. But perhaps the German soldiers were less intimidating than the big farmer from Harris.

Hansmann heard about a particularly ugly incident involving Johnson. As the story goes, a threshing crew came by, and “Henry got mad at somebody and just choked him out. The guy’s face was purple. It took four guys to pull him off.…I don’t even think he was drunk. They were working hard, those threshing crews.”

Victor may not have been choked out by Hank. But Victor “was afraid of him. I even sensed that,” Hansmann said. “My dad said a couple of times…Big Hank would come over and Victor didn’t even want to be in the same room. He [Big Hank] had a reputation. Maybe that’s why they were so isolated, too.”

But like Ruhland, Hansmann recognized that Big Hank Johnson had a softer side, especially when it came to children. “He was nice to us, and I didn’t realize this, because my sister was only four when I left home, but she loved him,” Hansmann said. “He would come by, and she would come running up and he would pick her up. He had two sides to him.”

Folks new to the area must have had a hard time keeping their Hank Johnsons straight. Besides Albin’s brother, there were multiple Hank Johnsons in the immediate vicinity, including Booze or Boozer Hank, Indian Hank and Long Hank or Lanky Hank. Booze Hank was known to go on a bender for a couple of weeks straight before deciding to sober up for a while. One of the Hank Johnsons unrelated to Albin was married to a woman named Jenny, who had a twin brother named Fritz Carlbom. (This is according to longtime Harris-area resident Jim Carlbom, in a summer 2017 discussion with the author.)

Fritz’s son, Jim, knew Big Hank—Albin’s brother—quite well. As a young man, years after the fire, Jim Carlbom worked for Big Hank, picking corn and doing other farm chores on the property once occupied by Albin and his family. Wearing a baseball cap that said something to the effect that Ford trucks are great and Chevys are junk, Jim Carlbom reminisced about Big Hank and company over a plate full of pancakes on a Wednesday morning at the Kaffe Stuga, a popular diner on the main drag of Harris. For the most part, he remembers Big Hank as a good fellow. “We used to go [to Hank and Mary’s place] and watch rasslin’ over there. Hank and Mary had a nice little place there. There wasn’t a nicer guy than Hank. Oh, my God,” Jim said, shaking his head and smiling at the memory.

That’s not to say Hank was a pushover. On the contrary, Big Hank wasn’t the kind of guy you wanted to pick a fight with, unless you could scrap like Farmer Lodge’s buddy Jack Dempsey. When the Johnson boys entered a drinking establishment, it was a bit like a scene out of the Old West, where the local tough guys push through the swinging doors and the dude at the piano suddenly stops playing. “You know, they were rough and tough guys,” Carlbom said. “When they walked in the bar, everything went quiet.…It did, because if [the other patrons] wanted their ass handed to them, they would hand it to them.”

Albin and his brothers worked for a time in the logging camps of Canada. It was physically demanding work, and they found themselves around some rough characters. Perhaps that’s where they learned to be scrappy in their own right. Lumbermen worked hard for the few bucks a day they earned in the World War I era. As The Canadian Encyclopedia puts it, the working conditions were quite dangerous and fights often broke out among the men, who lived together in tight quarters when they weren’t felling trees. “Considering the lumberjacks’ cloistered living arrangements and exacting working conditions, it is little wonder they stirred up havoc each spring upon their return to civilization. Stories of them unleashing their pent-up need to brawl, drink and carouse in places like Bytown (now Ottawa) are legendary.”

The historical record doesn’t indicate how much brawling, drinking and carousing Albin did in his lumberjacking days. But there’s reason to believe the man from Harris and his brothers held their own when the going got tough. “They were so damn strong. They were fighters,” Carlbom said. “I mean, if somebody wanted to fight—they lived a rough life in the logging camps up there. You took care of yourself. They had a lot of strength there. Hank used to show me how strong he was. Right up to the end he was splitting wood.”

Carlbom tells a story about a group of neighbors who, against their better judgment, risked having their asses handed to them by Big Hank—and failed spectacularly. As the story goes, the fellows got liquored up to the point they were brave enough to challenge Hank to a fight. One of the drunks ran halfway across a field toward Big Hank’s place before the booze got the best of him and he passed out mid-stride. “He woke up about two hundred, three hundred feet away from the house. He got so goddamned scared he shit his pants and ran all the way home,” Carlbom said with a laugh. If officers of the law had managed to track Albin down, perhaps they would have reacted in a similar manner, minus the part about soiling themselves. “I’m sure if the sheriff would have seen him he would have run the other way, too,” Carlbom said.

The Johnson brothers weren’t the only tough guys in the Harris area. A number of years later, another brawny fellow in town put his muscles to good use to help a cow that had fallen and couldn’t get back up. No doubt, the story has been embellished over the years. But as legend has it, the strongman lifted the cow with his bare hands while his friends retrieved a sling.

That same gentleman did a different kind of heavy lifting in a local bar after some other patrons unwisely started to give him and his friends a hard time. “There were six guys in there that started to give them hell, trying to start a fight. They always pick on the big guy. He walked up right between them and patted them on the back so hard he pushed them right down the bar [and said], ‘How you guys doing?’” Carlbom said. “There was no more fight in them.”

Carlbom recalled that Hank had a strong sense of honor, as well as a reputation as one of the toughest characters in town. After being told that his dog had made a meal of some of the neighbor’s chickens, Hank took decisive action. “Hank went outside with him and said, ‘Is that the dog, there?’ Yup. Hank reached up in the corncrib there, pulled out his gun and…Bam! He says, ‘We don’t want trouble with the neighbors.’ And he loved his dog,” Carlbom said.

While at least one of the Johnson boys was willing to kill his own dog to stay on good terms with a neighbor, Albin wasn’t capable of taking out his wife and seven children. At least that’s what Fritz Carlbom believed. “They said that Hank’s brother killed them and everything else. But I don’t know. My dad never believed that. He never believed that. He knew them real well,” Jim said.

Big Hank died on October 31, Halloween, in 1967. He was seventy-three years old. He’s buried alongside his wife, Mary, at Rush City’s First Lutheran Cemetery. The modest graves are just a few steps from the final resting place of Alvira Lundeen Johnson and her seven children.

No one will ever know what sorts of secrets Big Hank may have taken to his grave. But Jim Carlbom has an idea of what Hank would say about the Harris fire if the big Swede could rise out of the cold ground for a day.

Hank Johnson always claimed that the searchers didn’t look hard enough for Albin’s remains after the house burned to the ground, Carlbom said. Furthermore, Big Hank tried to make the case that Albin was in the house when the flames consumed the wooden structure. Hank theorized that the farm dwelling went up in flames so quickly, and the heat was so intense, that there wasn’t much left of the bodies afterward. “[Big Hank] said, ‘That old house was all built out of white oak, and it just about cremated him.’ That’s what he thought. It burned so hard,” Carlbom said.

What do folks remember about Albin? Because he has been gone for so long, there aren’t all that many surviving stories about him, other than some wild urban legends. More on that later. But according to some folks who were around when he was still alive, he had a reputation as a somber, surly man who seldom spoke and was capable of literally taking candy from children. That description seems to match up with the unsmiling, glowering mug portrayed on his wanted poster. “He was morose all the time,” said Jeanette Johnson, Alvira’s niece. “Never looked happy, never had a smile on his face.” Elsie Anderson, who lived near the Johnson family at the time of the fire, described him in a 1992 interview as “a mean man.” Elsie’s daughter, Mae Oscarson, remembered him as an introverted character who “never said a word.”

Entrance to the First Lutheran Cemetery, Rush City, Minnesota. Bill Klotz.

Jeanette Johnson heard stories of folks who felt sorry for Albin’s family. At times, the shopkeepers would send candy home with Albin to give to the kids. But by the time he got home, the treats were gone. “He would eat the candy and throw the bag away before he got home,” she said. “Evidently somebody had called Alvira and asked them if they got the candy. ‘No,’ she said. ‘They never got any candy.’”

It’s not clear what Alvira Lundeen saw in Albin, who was fourteen years her senior. “I never heard about why she was attracted to him,” Jeanette Johnson said. But the Lundeen and Johnson families lived close to each other in the Harris area. Schoolhouse dances, with a backdrop of music from fiddlers and accordion players, brought people together to have a good time. The atmosphere was festive. The homespun music was comfort food for the ears. Perhaps Alvira and Albin got better acquainted at one of those social functions.

“When we were kids, all the social activities took place in the schoolhouse,” Jeanette Johnson recalled. “My sister [Betty], she was just a tiny tot. But she knew this [Swedish folk song] ‘Nikolina.’ She stood on this stool there and sang ‘Nikolina.’ And then, those that had instruments could play. My father [Fred Peterson] had a little concertina and somebody else had a violin, and they cleared the chairs aside and had a dance on the floor. That was the center of social activity.”

For the Johnson brothers, it’s a good bet that the booze flowed freely at those social gatherings. But their dad was more straight-laced. Emil Johnson was considered a pillar of the community. Perhaps Alvira saw some good there. Maybe she thought Albin would take care of her.

Alvira Lundeen was united in marriage with Albin Johnson on December 16, 1922, according to county records. She was nineteen years, one month and one day old when she became Mrs. Albin Johnson. Albin was a few weeks shy of his thirty-third birthday. Christine Lundeen, Alvira’s mother, didn’t approve of the marriage. Maybe that was because Albin was fourteen years older than Alvira, the baby of the Lundeen family. Or perhaps she had a sense that Albin was capable of being violent. “Grandma had no time for him. She was very disappointed when Alvira married him. She just did not like him,” Jeanette Johnson said. “And that’s what mother [Freda Peterson, Alvira’s sister] said, too….Neighbors around there said that he… never smiled, never had a kind word to say to anybody.”

But not everybody saw it that way. Others described Albin as a hardworking man who was devoted to his family. He may have been down on his luck and a bit surly, but he was a good soul at heart, his defenders insisted. A reporter for the Chisago County Press was willing to give Albin the benefit of the doubt. In April 1933, the Press reported that Albin was “in his usual frame of mind” before the fire, “working hard for his family and taking an interest in his occupation.”

At least one neighbor, Caroll Ramberg, was among those who took a kindlier view of Albin. Ramberg apparently told another neighbor, Floyd Pinotti, that he had proof Albin was innocent. As Ramberg understood it, Albin was sitting in a bar called the Old Wagon Wheel at a time that “would have made it impossible for him to commit the murders,” Pinotti said in an interview. “He was convinced that Albin didn’t commit the murders.”

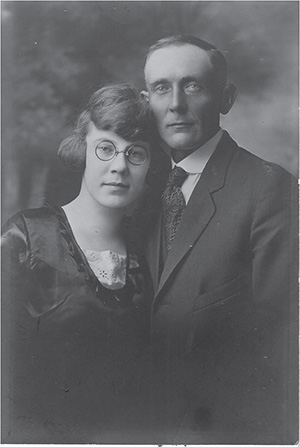

Freda Lundeen Peterson, left, and her sister Alvira Lundeen Johnson. Freda had a bad feeling about Albin Johnson. Author’s collection.

Albin’s brother-in-law, Harry Galpin, steadfastly defended the embattled man, going as far as to write a rambling, notarized affidavit that accuses law enforcement and public officials of covering up what really happened on April 11, 1933. Galpin claimed the authorities railroaded an innocent man. As far as Galpin was concerned, Johnson had died in the fire. The investigators, he claimed, either flat-out lied about key facts in the case, such as the conclusion that Johnson’s body wasn’t found, or they had some other nefarious motive for hiding “the truth” about the incident.

Two years before the fire, Albin’s name appeared in the local paper in connection with another incident: the botched robbery of the State Bank of Harris. But in this case he was just an innocent bystander. Albin was a customer in the bank at the time. The cashier was G.J. Stolberg, a relative of the judge who would later play a prominent role in the Albin Johnson case. As the Brainerd Daily Dispatch reported it, Bernard Blackfelner wounded cashier Stolberg when the bank employee “refused to obey the command to ‘stick ’em up.’” As Stolberg “made a dash for a rear room of the bank to call authorities,” the robber shot Stolberg in the arm, the newspaper reported.

The chase was on, and it soon got serious, as the authorities fired on the fleeing bandit in the towns of Wyoming and Forest Lake. After his car broke down in Forest Lake, Blackfelner was forced to “flee on foot for the nearby woods,” where he was apprehended by two “garage men,” the story continues. In the end, Blackfelner portrayed himself as a lovelorn young man who just wanted some cash to entertain the lady friends in his life. “Girls would not have anything to do with a fellow who doesn’t have a car and plenty of cash,” the robber whined, as quoted in the Daily Dispatch. “I had only 25 cents when I went to the Harris Bank this morning.…I wasn’t drunk. I just wanted the money to show a couple of girl friends a good time.”

Albin Johnson probably wasn’t concerned about entertaining any lady friends. But, like Blackfelner, he didn’t have much in his bank account. Like so many others of his era, Johnson struggled to support his growing young family. The Johnsons lived in a simple farmhouse, which lacked modern amenities that folks take for granted today.

Betty Kollas, Alvira’s niece, was only four when the house went up in flames, but she remembers visiting the site years later with her mother and father. She was ten or eleven at the time. Perhaps it was just a child’s imagination running wild, but she recalls that the place gave her the creeps. Young Betty couldn’t wait to get out of there. “I got this bad feeling. I was just freezing to death. I told Mom, ‘I want to go home.’ I had this horrible feeling. We didn’t waste any time up there. We took off,” she recalled, still shuddering at the memory more than eight decades later. Previously, when the Johnson family was still alive, she remembers at least one visit to the place. “I was pretty young. And I do remember being over there once,” Kollas said. “They kept water in big barrels in the house. And somebody lifted me up and showed me that it was water in these barrels. I just panicked. I remember that. I don’t think they had a pump close to the house.…We never kept any water in barrels.”

Lack of indoor plumbing was the least of the family’s problems. It was 1933, and the Great Depression was in full swing. Maybe that accounts for Albin Johnson’s angry disposition.

American farmers were used to hard times by then. During the 1920s and into the 1930s, a combination of rising debt, falling prices and lower real estate values proved to be a triple whammy for farmers. In Minnesota, from 1926 to 1932, more than 1,400 farms with roughly 258,000 combined acres fell into foreclosure, according to the Minnesota Historical Society.

Hitting the pause button on farm life, the family lived in the Twin Cities for a time. Betty Kollas gets the feeling that Albin wasn’t enthused about busting sod or raising cattle for a living. “Albin wanted to work away from the farm. He didn’t want to do farming,” she said.

Unfortunately for the Johnsons, things didn’t work out in the big city. It wasn’t long before Johnson and his family returned to Harris. Albin apparently made a good faith effort to find gainful employment. His brotherin-law, Matt Scherer, tried without luck to get Albin hired in the Rush City flour mill where Matt worked. Either the mill had no openings or the mill bosses simply weren’t interested in adding Albin to the payroll. It was one of many setbacks.

Johnson and his family settled into the farmhouse owned by Emil, his father. Bad luck, a disastrous economy, poor weather, lack of ability as a farmer or some combination of those factors proved to be Johnson’s downfall. “Those were tough years; 1933 was the depth of the Depression,” said Ruhland, the Twin Cities resident with family ties to the Johnsons. “The weather was bad, too. And that soil up there is not top-grade soil for farming. So I can see why they may have had a hard time of it. A lot of farmers probably were struggling at that time.”

Albin’s brother Big Hank took over the farm in the 1940s. Henry milked about a dozen cows and perhaps had some chickens and pigs, local researcher Dick Lindgren said.

People in those parts didn’t have much in the way of cash crops in those days. Maybe they grew enough corn to feed the animals, and that was about it. In essence, it was subsistence farming. “They didn’t have corn that would grow worth a damn that far north,” Lindgren said. Kollas said even the best farmers would have struggled to make a go of it on land that wasn’t suitable for crops. The family did have some cattle and a stretch of pasture for the animals. “I couldn’t imagine anybody farming on it. Part of it was swampland, part was a hill. You can’t grow much on a hill,” said Kollas, who owned and operated a ranch in Oregon with her husband, Bud.

Matt Scherer and Ellen Lundeen Scherer with their children. Matt tried to get Albin a job at a Rush City mill. Author’s collection.

Kollas said the county tried in vain to make the land more productive for farmers. “There was this humungous ditch that came right past [the Johnson] place,” Betty recalled. “I think the county was putting in a ditch to try and drain the water from that land, so it could be suitable for farming. And then they got this humungous storm that washed the dickens out of everything. It didn’t work out very well.”

When he was a kid, Hansmann could see the old Johnson property from his yard. Big Hank Johnson was still milking cows by hand there when Steve’s family was around in the 1960s. “He milked eight or ten cows by hand. They still had canned milk,” Hansmann said. “He had some crops, raised a hog or two to butcher and chickens—just a stereotypical little farmer.” But the farm has “never had good crops,” Hansmann said, shaking his head at the memory. “Never. There’s a lot of clay. The corn would always be stunted, crappy, weedy.”

For Albin, things hit bottom in 1933, when Emil Johnson evicted his son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren from the house. The family placed its belongings on a wagon, presumably a horse-drawn vehicle because the Johnsons were too poor to own a truck.

The St. Paul Dispatch reported on April 12 that Albin had visited a brother-in-law, Fred Peterson, a day before the fire. Peterson told the newspaper that Albin had said he was “practically set for the moving” and that he, Albin, had “located a farm home near Rush City.”

An April 13, 1933 story in the Chisago County Press implies that Albin was moving off the farm of his own free will. According to the story, “Mr. Johnson had decided to move off the farm, which was owned by his father, Emil Johnson, and intended to go to another farm place near Rush City.” But the story contradicts itself in the next sentence, which states that Albin had “received instructions from his father to leave 10 days ago and was packing a load Monday night.”

Freda and Fred Peterson. Fred was one of the last people to see Albin before the fire. Author’s collection.

“Can you imagine? It was Albin’s father that chased them out,” Jeanette Johnson said. “They had no place to go.”

As of Monday, April 10, the move appeared to be imminent. The family was, by all accounts, ready to say goodbye to the old farm place. The Johnsons had “beds, furniture, and other household goods in a wagon which stood outside the home and was also burned,” the Chisago County Press reported. The wagon stood on the property in the early morning hours of April 11, 1933.

That’s when the fire was discovered.