Training

Soldiers prepare to fight the Nation’s wars through tough, realistic and relevant training. That training pushes soldiers to their limit and beyond while maintaining high standards. This chapter will familiarize you with the system the Army uses to plan for, execute and assess the effectiveness of training and your responsibilities in making it happen. You must understand the importance of being proficient in your individual tasks so that the team can accomplish its collective tasks and mission. Force protection is a part of every operation and you can enhance force protection by knowing the rules of engagement.

Section I - Army Training Management

Leader Training and Development

Task, Conditions, and Standards

Section II - Individual Training

Section III - Force Protection

For more information on training, see FM 7-0 (25-100), Training the Force, FM 7-1 (25-101), Battle Focused Training, and AR 350-1, Army Training and Education.

For more information on common tasks and skills, see STP 21-1-SMCT, Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks, and FM 3-21.75 (21-75), Combat Skills of the Soldier.

For more information on physical training, see FM 3-22.20 (21-20), Physical Fitness Training.

For more information on safety, see FM 5-19 (100-14), Risk Management, AR 385-10, Army Safety Program, and DA PAM 385-1, Small Unit Safety Officer/NCO Guide.

For more information on force protection and antiterrorism, see FM 3-07.2 (100-35), Force Protection, and AR 525-13, Antiterrorism.

For more information on guard duty, see FM 3-21.6 (22-6), Guard Duty.

SECTION I: ARMY TRAINING MANAGEMENT

5-1. Every soldier, NCO, warrant officer, and officer has one primary mission—to be trained and ready to fight and win our Nations wars. Success in battle does not happen by accident; it is a direct result of tough, realistic, and challenging training. We exist as an Army to deter war, or if deterrence fails, to reestablish peace through victory in combat. To accomplish this, our Armed Forces must be able to perform their assigned strategic, operational, and tactical missions. Now for deterrence to be effective, potential enemies must know with certainty that the Army has the credible, demonstrable capability to mobilize, deploy, fight, sustain, and win any conflict.

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and success of liberty.

John F. Kennedy

5-2. Training is that process that melds human and materiel resources into these required capabilities. The Army has an obligation to the American people to ensure its soldiers go into battle with the assurance of success and survival. This is an obligation that only rigorous and realistic training, conducted to standard, can fulfill.

5-3. We train the way we fight because our history shows the direct relation between realistic training and success on the battlefield. Today’s leaders must apply the lessons of history in planning training for tomorrow’s battles. We can trace the connection between training and success in battle to our Army’s earliest experiences during the American Revolution. General George Washington had long sensed the need for uniform training and organization, so he secured the appointment of Baron Von Steuben as Inspector General in charge of training. Von Steuben clearly understood the difference between the American citizen soldier and the European professional. He noted that American soldiers had to be told why they did things before they would do them well, and he applied this same philosophy in his training which helped the continental soldiers understand and endure the rigorous and demanding training he put them through. After Valley Forge, Continentals would fight on equal terms with British regulars. Von Steuben began the tradition of effective unit training that today still develops leaders and forges battle-ready units for the Army.

With 2,000 years of examples behind us we have no excuses when fighting, for not fighting well.

T.E. Lawrence

5-4. Field Manual 7-0, Training the Force, points out that today our Army must meet the challenge of a wider range of threats and a more complex set of operating environments while incorporating new and diverse technologies. The Army meets these challenges through its core competencies: shape the security environment, prompt response, mobilization, forcible entry operations, sustained land dominance, and support civil authorities. Field Manual 7-0 is the Army’s capstone training doctrine and is applicable to all units, at all levels, and in all components. While its focus is principally at division and below, FM 7-0 provides the essential fundamentals for all individual, leader and unit training.

5-5. Training for warfighting is our number one priority in peace and war. Warfighting readiness comes from tactical and technical competence and confidence. Competence relates to the ability to fight our doctrine through tactical and technical execution. Confidence is the individual and collective belief that we can do all things better than the adversary and that our units possess the trust and will to accomplish the mission.

To lead an untrained people to war is to throw them away.

Confucius

5-6. Field Manual 7-0 provides the training and leader development methods that are the basis for developing competent and confident soldiers and the units that will win decisively in any environment. Training is the means to achieve tactical and technical competence for specific tasks, conditions, and standards. Leader Development is the deliberate, continuous, sequential and progressive process, based on values, that develops soldiers and civilians into competent and confident leaders capable of decisive action.

5-7. Closing the gap between training, leader development, and battlefield performance has always been the critical challenge for any Army. Overcoming this challenge requires achieving the correct balance between training management and training execution. Training management focuses leaders on the science of training in terms of resource efficiencies (People, time, ammo, etc.) measured against tasks and standards. Training execution focuses leaders on the art of leadership to develop trust, will, and teamwork under varying conditions. Leaders integrate this science and art to identify the right tasks, conditions, and standards in training, foster unit will and spirit, and then adapt to the battlefield to win decisively.

HOW THE SYSTEM OPERATES

5-8. Soldier and leader training and development continue in all units in the active and reserve components. Using the institutional foundation as the basis, training in organizations and units focuses and hones individual and team skills and knowledge. This requires all soldiers, at some level, to take responsibility for the training and readiness of the unit.

For they had learned that true safety was to be found in long previous training, and not in eloquent exhortations uttered when they were going into action.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponesian Wars

5-9. Unit training consists of three components: collective training, leader development and individual training. Collective training comes from the unit’s mission essential task list (METL) and mission training plans (MTP). Leader development is embedded in collective training tasks and in some separate individual leader focused training. Individual training establishes, improves, and sustains individual soldier proficiency in tasks directly related to the unit’s METL. Commanders plan and conduct unit collective training to prepare soldiers and leaders for unit missions.

COMMANDER’S RESPONSIBILITY

5-10. The commander is responsible for the wartime readiness of the entire unit. The commander is therefore the primary trainer of the organization and is responsible for ensuring that all training is conducted to standard. This is a top priority of the commander, and the command climate must reflect this priority. He analyzes the unit’s wartime mission and develops the unit’s METL. Then, using appropriate doctrine and the MTP, the commander plans training and briefs the training plan to the next higher commander. The next higher commander provides resources, protects the training from interference, and assesses the training.

5-11. The commander’s involvement and presence in planning, preparing, executing and assessing unit training to standards is key to effective unit training. They must ensure MTP standards are met during all training. If a squad, platoon, or company fails to meet the established standard for identified METL tasks, the unit must retrain until the tasks are performed to standard. Sustaining METL proficiency is the critical factor commanders adhere to when training small units.

NCO RESPONSIBILITY

5-12. A great strength of the US Army is its professional NCO Corps. NCOs take pride in being responsible for the individual training of soldiers, crews, and small teams. They continue the development of new soldiers when they arrive in the unit. NCOs train soldiers to the non-negotiable standards published in MTPs and soldier’s training publications (STPs), including the common task manual. NCOs provide commanders with assessments of individual and crew/team proficiency to support the training management process.

5-13. Individual and crew/team training is an integral part of unit training. Taking advantage of every training opportunity is a valuable talent of NCOs. NCOs routinely help integrate individual training with unit training to ensure soldiers can perform their tasks to prescribed standard as a team member. In this way they assist the commander in forging a team capable of performing the unit’s METL to the prescribed standard and accomplishing all assigned missions.

YOUR RESPONSIBILITY

5-14. You, as an individual soldier, are responsible for performing your individual tasks to the prescribed standard. Training is the cornerstone of success. It is a full time job in peacetime and continues in wartime. In battle, you and your unit will fight as well or as poorly as you and your fellow soldiers trained. Your proficiency will make a difference.

The Best Machinegunner in the 101st

Private “Tex” McMorries was a machine gunner in Company G, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, during World War II. During Operation Market Garden, the 501st landed in drop zones near the city of Veghel, Holland. On 24 September 1944 the Germans attacked to recapture the town. Private McMorries and his squad were holding a critical roadblock on the Germans’ likeliest avenue of approach to the village.

When German reconnaissance had determined that the roadblock was a weak area in the American line, they attacked. In the initial firefight the Germans poured a tremendous amount of firepower on the American position and six soldiers were wounded. The enemy advanced to within 100 yards of the position when Private McMorries opened fire with his machine gun, halting the German advance. The Germans attacked again several times but the Americans threw them back each time.

Private McMorries never received an award for his action that day. When asked about his feelings on not being recognized with an award, Tex McMorries replied, “I wanted no credit for my little part in 101st history. I am only proud that if you asked a man of Company G, 501st, who was the best machine gunner in the 101st, he will name me. That is my decoration. It can’t be worn, only felt. It is the only one I care for now.” He fulfilled his obligations to his unit and to his country. His actions as an infantryman characterized the requirements that must be possessed by all soldiers to ensure their effectiveness and ability to fight and win on the battlefield.

5-15. You received a lot of critical skills training in Basic Combat Training (BCT) and Advanced Individual Training (AIT) or in officer basic course. But in your unit you learn more skills and how to function as a member of the team under conditions that approximate battlefield conditions. To maintain proficiency and gain new skills requires continual self-development, which may take the form of training or education.

5-16. Soldier Training Publications (STPs) contain individual critical tasks, professional development information, and other training information that are important to your success as a soldier. Your MOS-specifc STP helps you maintain your task performance proficiency and it aids unit leaders, unit trainers, and commanders to train subordinates to perform their individual critical tasks to the prescribed standard. STPs help standardize individual training for the whole Army.

Gunners that can’t shoot will die.

The Battalion Commander’s Handbook

5-17. Individual tasks are the building blocks to collective tasks. Your first-line supervisor will identify those individual tasks that support your units mission essential task list (METL). If you have questions about which tasks you must perform, ask your first-line supervisor for clarification, assistance and guidance. Your first-line supervisor knows how to perform each task or can direct you to the appropriate soldier training publications, field manuals, technical manuals, and Army regulations. A good habit is to periodically ask your supervisor or fellow soldier to check your task performance to ensure that you can perform each task you are responsible for to the prescribed standard.

Training then–both good and bad–is habit forming. The difference is that one develops the battlefield habits that win; the other gets you killed.

SMA Glen E. Morrell

LEADER TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT

5-18. Competent and confident leaders are a prerequisite to training ready units. Leader training and leader development are integral parts of unit readiness. Leaders are soldiers first and must be technically and tactically proficient in basic soldier skills. They are also adaptive, capable of sensing their environment, adjusting the plan when appropriate and properly applying the proficiency acquired through training.

5-19. Leader training is an expansion of these skills that qualifies them to lead other soldiers. As such, the doctrine and principles of training leader tasks is the same as that for any other task. Leader training occurs in the institutional Army, the unit, the combat training centers, and through self-development. Leader training is a part of leader development.

5-20. Leader development is the deliberate, continuous, sequential and progressive process, grounded in Army values, that grows soldiers into competent and confident leaders capable of decisive action. Leader development comes from the knowledge, skills, and experiences gained through institutional training and education, organizational training, operational experience, and self-development. In always doing your best during training you are developing leader skills and attributes. But this won’t be enough to provide the insight, intuition and judgment necessary in combat. Self-study and training is also essential. It begins with a candid assessment of your strengths and weaknesses and then, with your supervisor, develop a program to build on those strengths and minimize those weaknesses. Often this involves reading about leadership, military history, or MOS-related subjects, for example. But it also may include other activities, such as college or correspondence courses.

The most enduring legacy that we can leave for our future generations of noncommissioned officers will be leader development.

SMA Julius W. Gates

5-21. Another great resource available to help you in self-development and leaders for training subordinates is US Army Training and Doctrine Command’s digital library at http://www.adtdl.army.mil/atdls.htm. The digital library database contains publications and additional information not included in your STP. You can access this information through the internet and through your Army Knowledge Online (AKO) account.

BATTLE FOCUS TRAINING MANAGEMENT

5-22. The foundation of the training process is the Army training management cycle. The training management cycle and the necessary guidelines on how to plan, execute, and assess training and leader development is also found in FM 7-0. Understanding how the Army trains the Army to fight is key to successful joint, multinational, interagency, and combined arms operations. Effective training leads to units that execute the Army’s core competencies and capabilities.

5-23. Training management starts with the unit mission. From mission, unit leaders develop the mission essential task list (METL). The METL is an unconstrained statement of the tasks required to accomplish wartime missions. The availability of resources does not affect METL development, but resources for training are constrained and compete with other missions and requirements. Therefore, leaders develop the long-range, short-range, and near-term training plans to effectively utilize available resources to train for proficiency on METL tasks.

5-24. Planning is an extension of the battle focus concept that links organizational METL with the subsequent preparation, execution, and evaluation of training. The planning process ensures continuous coordination from long range planning, through short-range planning to near-term planning, which ultimately leads to training execution. The commander’s assessment provides direction and focus to the planning process. Through the training planning process, the commander’s guidance (training vision, goals, and priorities) is melded together with the METL and the training assessment into manageable training plans.

5-25. Long-range training plans:

• Are about one year out for AC battalion level organizations.

• Are about three years out for RC battalion level organizations.

• Disseminate METL and battle tasks.

• Establish training objectives for each METL.

• Schedule projected major training events.

• Identify long lead-time resources and allocate major resources such as major training area rotations.

• Identify major training support systems products and services and identify new requirements.

5-26. Short-range training plans:

• Are about three months for AC battalion level organizations.

• Are about one year out for RC battalion level organizations.

• Refine and expand upon appropriate portions of long-range plan.

• Cross-reference each training event with specific training objectives.

• Identify and allocate short-range lead time resources such as local training facilities.

5-27. Near-term training plans:

• Refine and expand upon short-range plan through conduct of training meetings.

• Determine best sequence for training.

• Provide specific guidance for trainers.

• Allocate training support systems, products and services, simulators and simulations, and similar resources to specific trainers.

• Publish detailed training schedules.

• Provide basis for executing and evaluating training.

5-28. Properly developed training plans will—

• Maintain a consistent battle focus.

• Be coordinated with habitually task organized supporting organizations.

• Focus on the correct time horizon.

• Be concerned with future proficiency.

• Incorporate risk management into all training plans.

• Establish organizational stability.

• Make the most efficient use of resources.

5-29. After training plans are developed, units execute training by preparing, conducting, and recovering from training. The process continues with training evaluations that provide bottom-up input to the organizational assessment. These assessments provide necessary feedback to the senior commander that assist in preparing the training assessment.

TRAINING AND TIME MANAGEMENT

5-30. The purpose of time management is to achieve and sustain technical and tactical competence and maintain training proficiency at an acceptable level. Time management systems identify, focus and protect prime time training periods and the resources to support the training. There are three periods in this time management cycle: green, amber and red.

Green

5-31. The training focus of units in green periods is multiechelon; collective training that leads to METL proficiency. This period coincides with the availability of major training resources and key training facilities and devices. Organizations in Green periods conduct planned training without distraction and external taskings.

Amber

5-32. The focus of units in amber periods is on training proficiency at the platoon, squad and crew level. Individual self-development is maximized through the use of education centers and distributed learning. Organizations in Amber periods are assigned support taskings beyond the capability of those units in the Red period. Commanders must strive for minimal disruption to Amber units’ training programs.

Red

5-33. The training focus of units in the Red periods is on maximizing self-development opportunities to improve leader and individual task proficiency. Units in the Red periods execute details and other administrative requirements and allow the maximum number of soldiers to take leave. Block leave is a technique that permits an entire unit to take leave for a designated period of time. Commanders maintain unit integrity when executing administrative and support requirements i.e. Squad, Team, Platoon integrity. This exercises the chain of command and provides individual training opportunities for first line leaders.

TOP-DOWN/BOTTOM-UP APPROACH TO TRAINING

5-34. The Top-Down/Bottom-Up approach to training is a team effort in which senior leader provide training focus, direction and resources, and junior leaders provide feedback on unit training proficiency, identify specific unit training needs, and execute training to standard in accordance with the approved plan. It is a team effort that maintains training focus, establishes training priorities, and enables effective communication between command echelons.

5-35. Guidance based on wartime mission and priorities flows from the top-down and results in subordinate units having to identify specific collective and individual tasks that support the higher unit’s mission. Input from the bottom up is essential because it identifies training needs to achieve task proficiency on identified collective and individual tasks. Leaders at all levels communicate with each other about requirements and planning, preparing, executing, and evaluating training.

5-36. Some leaders centralize planning to provide a consistent training focus throughout the organization. However, they decentralize execution to ensure that the conduct of mission-related training sustains strengths and overcomes the weakness unique to each unit. Decentralize execution promotes subordinates leaders’ initiative to train their units, but does not mean senior leaders give up their responsibilities to supervise training, develop leaders, and provide feedback.

BATTLE FOCUS

5-37. Battle focus is a concept used to derive peacetime training requirements from assigned and anticipated missions. The priority of training in units is to train to standard on wartime missions. Battle focus guides the planning, preparation, executing, and assessment of each organization’s training programs to ensure its members train as they will fight. Battle focus training is critical throughout the entire training process and is used by commanders to allocate resources for training based on wartime and operational mission requirements.

5-38. Battle focus enables commanders and staffs at all echelons to structure a training program that copes with non-mission related requirements while focusing on mission essential training activities. In garrison, peacetime operations most units cannot attain proficiency to standard on every task whether due to time or other resource constraints. Battle focus helps the commander to design a successful training program by consciously focusing on a reduced number of critical tasks that are essential to mission accomplishment.

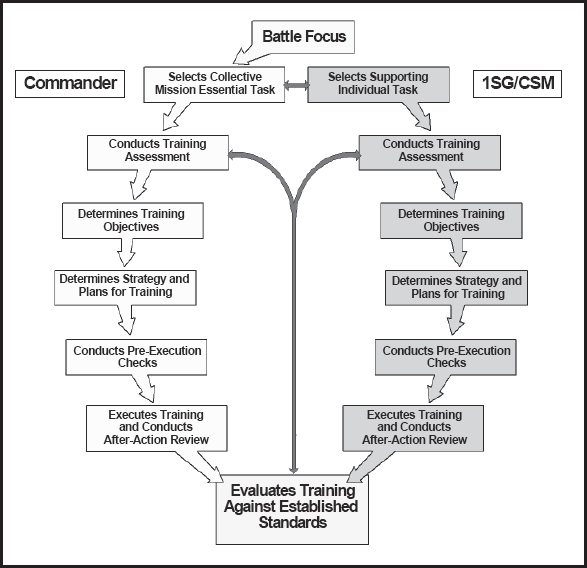

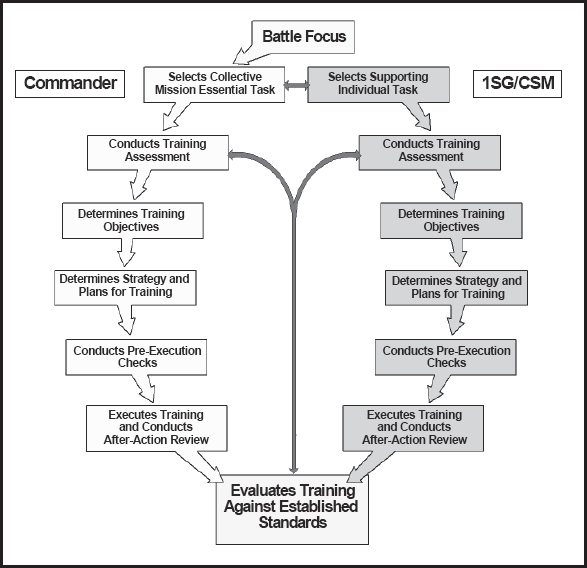

Figure 5-1. Integration of Collective and Individual Training

5-39. A critical aspect of the battle-focus concept is to understand the responsibility for and the linkage between the collective mission essential tasks and the individual tasks that support them. The commander and the command sergeant major or the first sergeant (CSM/1SG) must jointly coordinate the collective mission-essential tasks and individual training tasks on which the unit will concentrate its efforts during a given period. The CSM/1SG must select the specific individual tasks that support each collective task to be trained. Although NCOs have a primary role in training and sustaining individual soldier skills, officers at every echelon remain responsible for training to established standards during both individual and collective training. Battle focus is applied to all missions across the full spectrum of operations. Figure 5-1 shows this process.

TRAINING SCHEDULES

5-40. Near-term planning results in a detailed training schedule. Backward planning is used to ensure that all tasks can be executed in the time available and that tasks depending on other tasks are executed in the correct sequence. Training is considered “Locked In” when the battalion commander signs the training schedule. At a minimum, it should—

• Specify when training starts and where it takes place.

• Allocate adequate time for scheduled training and additional training as required to correct anticipated deficiencies.

• Specify individual, leader, and collective tasks to be trained.

• Provide concurrent training topics that will efficiently use available training time.

• Specify who conducts the training and who evaluates the training.

• Provide administrative information concerning uniform, weapon, equipment, references, and safety precautions.

5-41. Senior commanders establish policies to minimize changes to the training schedule. Training is locked in when training schedules are published. Command responsibility is established to as follows—

• The company commander drafts the training schedule.

• The battalion commander approves and signs the schedule and provides necessary administrative support.

• The brigade commander reviews each training schedule published in his command.

• The division commander reviews selected training schedules in detail and the complete list of organization wide training highlights developed by the division staff.

CONDUCT OF TRAINING

5-42. Ideally, training is executed using the crawl-walk-run approach. This allows and promotes an objective standard-based approach to training. Training starts at this level. Crawl events are relatively simple to conduct and require minimum support from the unit. But after the crawl stage, training becomes incrementally more difficult, requiring more resources from the unit and home station and increasing the level of realism. At the run stage, the level of difficulty for the training event intensifies. Run stage training requires optimum resources and ideally approaches the level of realism expected in combat. Progression from the walk to the run stage for a particular task may occur during a one-day training exercise or may require a succession of training periods over time. Achievement of the Army standard determines progression between stages.

5-43. In crawl-walk-run training, the tasks and the standard remain the same; however, the conditions under which they are trained change. For example, commanders may change the conditions by increasing the difficulty of the conditions under which the task is being performed, increasing the tempo of the task training, increasing the number of tasks being trained, or by increasing the number of personnel involved in the training. Whichever approach is used, it is important that all leaders and soldiers involved understand which stage they are currently training and understand the Army standard.

5-44. An example of the crawl-walk-run approach occurs in the execution of the infantry platoon task “conduct an attack.” In the crawl stage, the platoon leader describes the task step-by-step, including what each soldier does. In the walk stage, the platoon conducts a rehearsal of the attack at a step-by-step pace. In the run stage, the platoon executes the task at combat speed under tactical conditions against an opposing force (OPFOR). Ideally this includes multiple iterations under increasingly difficult conditions—at night, for example. Each time they practice the attack, the platoon strives to achieve the tactical objective to the standard described in the training and evaluation outline (T&EO) for “conduct an attack.”

THE AFTER-ACTION REVIEW

5-45. The After-action Review (AAR) is a structured review process that allows all training participants to discover for themselves what happened, why it happened, and how it can be done better. The unit leader or an observer of the training can lead the discussion, but the key to having an effective AAR is active involvment by all the soldiers who took part in the training. All soldiers have a unique perspective of any given event and should contribute to the AAR.

5-46. An effective AAR will focus on the training objectives and whether the unit met the appropriate standards (not on who won or lost). The result of an AAR is that soldiers learn lessons from the training. That requires maximum participation of soldiers and leaders (including OPFOR) so those lessons learned can be shared.

Most coaches study the films when they lose, I study them when we win—to see if I can figure out what I did right.

Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant

5-47. There are four distinct parts of an AAR. First, soldiers who participated in the training review what was supposed to happen. Secondly, you have to establish what, in fact, did happen, including the OPFOR’s point of view. Then you determine what was right or wrong with what happened, with respect to applicable standards. Finally—and this is vitally important—you have to determine how the task should be done differently next time.

Hotwash—An AAR at the Combat Maneuver Training Center Hohenfels, Germany.

5-48. An AAR should occur immediately after a training event and may result in some additional training. You should expect to retrain on any task that was not conducted to standard. That retraining will probably happen at the earliest opportunity, if not immediately. Training is incomplete until the task is trained to standard. Soldiers will remember the standard enforced, not the one discussed. This same approach is useful in virtual and constructive simulation as a means to train battle staffs and subordinate organizations.

AARs are one of the best tools we have… AARs must be a two-way communication between the NCO and the soldiers. They are not lectures.

Center for Army Lessons Learned

5-49. Some training time during the week should be devoted to the small-unit leader (such as a squad leader or a vehicle commander) to train his soldiers. This enhances readiness and cohesion and it also allows the junior NCO to learn and exercise the Army’s training-management system at the lowest level. The key is to train the trainer so that he can train his soldiers. This requires the NCO to identify essential soldier and small-unit and team tasks (drills) that support unit METL.

5-50. NCOs are the primary trainers of junior enlisted soldiers. Sergeant’s Time Training (STT) affords a prime opportunity for developing first line leaders while they gain their soldier’s confidence. Active component commanders should institute STT as a regular part of the units training program. This will allow NCOs to train their soldiers on certain tasks in a small group environment.

5-51. Sergeant’s Time Training is a hands-on, practical training for soldiers given by their NCOs. It provides the NCO with resources and the authority to bring training publications or technical manuals to life and develops the trust between leader and led to ensure success in combat. In the active component, the chain of command and the NCO support channel implement this training by scheduling five continuous uninterrupted hours each week to STT. STT may be difficult for reserve component (RC) units to accomplish during a typical training assembly or even during annual training, but RC units should plan and conduct STT after mobilization.

5-52. NCOs or first line leaders are the primary trainers during STT and should strive for 100% of their soldiers present for training. Platoon sergeants assist in the preparation and execution of training and officers provide the METL resources (time, personnel and equipment) to conduct training and provide feedback to commanders. Senior NCOs should protect this program against distractions and provide leadership and guidance as necessary to the first-line leaders. NCOs conduct a training assessment and recommend what individual tasks or crew and squad collective training they need to conduct during STT. Topics are based on the small unit leader’s assessment of training areas that need special attention. Sergeant’s Time Training may be used to train soldiers in a low-density MOS by consolidating soldiers across battalion/brigade and other organizations.

5-53. Many units have their own way of conducting STT but some aspects are universal. For example, STT is standard oriented and not time oriented. In other words, expect to train on a task until soldiers are proficient in that task. In addition, all first-line supervisors maintain a file with the task, conditions, and standards for each task and each soldier’s proficiency in those tasks.

5-54. At the end of Sergeant’s Time Training, the supervisor will assesses the training conducted and makes recommendations for future training. If the task could not be trained to standard, then the supervisor should reschedule the same task for a future Sergeant’s Time.

TASK, CONDITIONS, AND STANDARDS

5-55. Task, conditions, and standards are the Army’s formula for training tasks to standard. You should learn the specific conditions and standards before training a task so you understand what is expected of you.

• Task: A clearly defined and measurable activity accomplished by individuals and organizations. Tasks are specific activities that contribute to the accomplishment of encompassing missions or other requirements.

• Conditions: The circumstances and environment in which the task is to be performed.

• Standard: The minimum acceptable proficiency required in the performance of the training task under a specific set of conditions.

SECTION II: INDIVIDUAL SOLDIER TRAINING

5-56. The competence of the individual soldier is the heart of any unit’s ability to conduct its mission. Individual training is the instruction of soldiers to perform their critical individual tasks to the prescribed standard. A soldier must be capable of performing these tasks in order to serve as a viable member of a team and to contribute to the accomplishment of a unit’s missions. Maintain proficiency in your individual tasks to build self-confidence and trust among your fellow soldiers.

5-57. Individual training is initially conducted in the training base in a formal school setting but subsequently may also be provided via distributed learning that a soldier must complete in his unit or at a distance learning site. Initial individual training is often conducted with commercial firms, by specialized Army activities at civilian institutions, and units in the field.

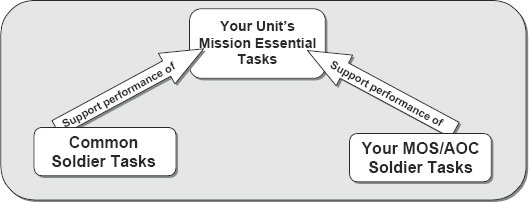

Figure 5-2. Individual Task to METL Relationship

5-58. Individual training is also conducted in the unit on tasks not trained in formal training or to sustain task performance proficiency. Army training is task based. This is how the Army ensures units and soldiers are trained to accomplish unit missions. Army units identify their mission essential tasks, the collective tasks that the unit must be able to perform to accomplish its mission. For your unit to accomplish its mission, every soldier in your unit must first be able to perform his individual tasks that support those mission essential tasks. Figure 5-2 shows this relationship between individual tasks and the METL.

PHYSICAL FITNESS

5-59. Your physical fitness has a direct impact on combat readiness. A soldier who is physically unfit for duty is as much a casualty as if an enemy bullet had hit him. When that unfitness is a result of the soldier’s own carelessness or, worse yet, of his own misconduct, he is guilty of a breach of trust with his comrades, the Army and his fellow Americans. The Army expects you to keep in top physical condition and for that purpose provides you with good food, clothing, sanitary facilities, physical training, and medical care.

5-60. Your unit’s physical fitness program is but one component of total fitness. Some of the others are weight control, diet and nutrition, stress management, dental health, and spiritual and ethical fitness, as well as the avoidance of hypertension, substance abuse, and tobacco use.

5-61. Even though soldiers are physically fit some still may become ill. Daily “sick call” is aimed at revealing and halting illness at its beginning. If you feel below par in the morning, Army doctors want to see you immediately. They will diagnose and treat your ailment before it gets worse. This is true regardless of where you are stationed. Army medical experts have made and continue to make surveys of much of the world so that they can diagnose, treat, and control the diseases found there.

PHYSICAL TRAINING

5-62. An important part of overall fitness is physical training. The objective of physical training in the Army is to improve soldiers’ abilities to meet the physical demands of war. Any physical training that results in numerous injuries or accidents works against this goal. Good, sound physical training challenges soldiers but does not place them at undue risk nor lead to situations where accidents or injuries are likely to occur.

5-63. The Army’s physical fitness training program includes the USAR and ARNG, encompasses all ages and ranks, and both male and female soldiers. Its purpose is to physically condition all soldiers throughout their careers beginning with basic combat training (BCT). It also includes soldiers with limiting physical profiles who must also participate in physical fitness training.

Unit Programs

5-64. There are many types of units in the Army, and their missions often require different levels of fitness. TOE and TDA units must emphasize attaining and maintaining the fitness level required for the mission. The unit’s standards may exceed the Army’s minimums. Army Regulation 350-1 authorizes commanders to set higher standards that are justified by mission requirements.

5-65. The considerations for the active component also apply to the reserve component. However, since members of RC units cannot participate together in collective physical training on a regular basis, RC unit programs must focus on the individual’s fitness responsibilities and efforts. But commanders must still ensure that the unit’s fitness level and individual PT programs are maintained. Master Fitness Trainers (MFT) can assist RC commanders and soldiers.

5-66. Soldiers everywhere must accept responsibility for their own physical fitness. This is especially true for those assigned to duty positions and organizations that offer little opportunity to participate in collective unit PT programs. Some examples are Headquarters, Department of the Army (HQDA) and Major Army Command (MACOM) staffs, hospitals, service school staff and faculty, and recruiting.

Special Programs

5-67. The day-to-day unit PT program conducted for most soldiers may not be appropriate for all unit members. Some of them may not be able to exercise at the intensity or duration best suited to their needs. At least three groups of soldiers may need special PT programs. They are as follows:

• Those who fail the APFT and do not have medical profiles.

• Those who are overweight/overfat according to AR 600-9.

• Those who have either permanent or temporary medical profiles.

5-68. Leaders should also give special consideration to soldiers who are age 40 or older and to recent arrivals who cannot meet the standards of their new unit. Special programs must be tailored to each soldier’s needs, and trained, knowledgeable leaders should develop and conduct them. This training should be conducted with the unit. If this is impossible, it should at least occur at the same time. There must be a positive approach to all special fitness training.

FIELDCRAFT

5-69. Much can be done to discipline soldiers in garrison; however, in the field, whether in training, combat or on an operational mission, whether under blue skies, in storms, cold and heat, or marching, all soldiers must endure regardless of the hardships. Fieldcraft are skills, knowledge and adaptability that helps soldiers operate in the field so as to spend less effort fighting the elements and more effort fighting the enemy. Being an expert in fieldcraft reduces the likelihood of you being a casualty due to cold or heat injuries, for example.

5-70. Another challenge for leaders is to develop and implement sleep plans that will recharge soldiers and accomplish the mission. All soldiers, but particularly leaders, are susceptible to sleep deprivation. Many poor decisions have been made by leaders who went without sleep for unnecessarily long periods of time, putting their soldiers and units at additional risk. Leaders must balance sleep and mission requirements to maintain mental alertness and physical readiness.

INDIVIDUAL COMBAT SKILLS

5-71. Regardless of where you expect to be on or near the battlefield, every soldier must be proficient in the performance of certain tasks to give him the best possible chance for survival. Listed below are selected combat tasks that are important for every soldier whether in combat arms (CA), combat support (CS), and combat service support (CSS) branches or MOSs. The inclusion or exclusion on this list of any particular individual task does not imply that other common tasks are less important or that any MOS-specific tasks are less important.

Building an individual fighting position during Operation Iraqi Freedom.

5-72. You can find the complete tasks with the performance measures in Appendix A or in STP 21-1-SMCT, Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks. Tasks, conditions and standards sometimes change, so periodically check for them in STP 21-1-SMCT and ensure that you can perform the listed tasks to the prescribed standard.

SHOOT

5-73. Action: Engage Targets with an M16A1 or M16A2 Rifle. For more information see FM 3-22.9, M16A1 and M16A2 Rifle Marksmanship.

• Conditions: Given an M16A1 or M16A2 rifle, magazines, ammunition, individual combat equipment, and stationary or moving targets (personnel or equipment) at engageable ranges.

• Standards: Detected and determined range to targets. Fired the M16A1 or M16A2 rifle, engaged targets in assigned sector of fire. Applied correct marksmanship fundamentals and target engagement techniques so that each target was hit or suppressed. Hit 60 percent or more of the targets in assigned sector of fire.

MOVE

5-74. Task : Navigate from One Point on the Ground to Another Point while dismounted (071-329-1006).

• Conditions: Given a standard topographic map of the area, scale 1:50,000, a coordinate scale and protractor, a compass, and writing material.

• Standards: Move on foot to a designated point at a rate of 3,000 meters in an hour.

5-75. Task: Move Over, Through, or Around Obstacles (Except Minefields) (071-326-0503).

• Conditions: Given individual weapon, load-carrying equipment (LCE), one smoke grenade, wood or grass mats or chicken wire, a grappling hook, wrapping material, wire cutters (optional) and a buddy. During daylight or darkness, you are at a field location, moving over a route with natural and man-made crossings and obstacles (walls and barbed wire entanglements).

• Standards: Approached within 100 meters of a suspected enemy position over a specified route, negotiated each obstacle encountered within the time designated while retaining all of your equipment without becoming a casualty to a bobby trap or early warning device.

COMMUNICATE

5-76. Task: Perform Voice Communication (113-571-1022).

• Conditions: Given: 1) One operational radio set for each member, warmed up and set to the net frequency. 2) A call sign information card consisting of: Net member duty position, net call sign, suffix list, and a message to be transmitted. 3) Situation: the net is considered to be secure and authenication is not required.

• Standards: Enter a radio net, send a message, and leave a radio net using the proper call signs, call sign sequence, prowords, and phonetic alphabet and numerals with 100 percent accuracy.

SURVIVE

5-77. Task: React to Chemical or Biological Attack/Hazard (031-503- 1019).

• Conditions: Given mission-oriented protective posture (MOPP) gear, a protective mask, individual decontaminating kits, and a tactical environment in which chemical and biological (CB) weapons have been or may be used by the enemy. You are in MOPP Level 1, and one or more of the following automatic masking criteria happens:

a. A chemical alarm sounds.

b. A positive reading is obtained on detector paper.

c. Individuals exhibit symptoms of CB agent poisoning.

d. You observe a contamination marker.

e. Your supervisor tells you to mask.

f. You see personnel wearing protective mask.

g. You observe other signs of a possible CB attack.

• Standards: Do not become a casualty. Identify chemical contamination markers with 100 percent accuracy, and notify your supervisor. Start the steps to decontaminate yourself within 1 minute of finding chemical contamination. Decontaminate your individual equipment after you have completely decontaminated yourself.

5-78. Task: Decontaminate Yourself and Individual Equipment Using Chemical Decontaminating Kits (031-503-1013).

• Conditions: You are at mission-oriented protection posture (MOPP) 2 with remaining MOPP gear available. You have a full canteen of water, a poncho, load bearing equipment (LBE), assigned decontaminating kit(s), and applicable technical manuals (TMs). Your skin is contaminated or has been exposed to chemical agents, or you have passed through a chemically contaminated area.

• Standards: Start the steps to decontaminate your skin and/or eyes within 1 minute after you find they are contaminated. Decontaminate all exposed skin and your eyes as necessary before chemical agent symptoms occur. Decontaminate all personal equipment for liquid contamination after decontaminating your skin, face and eyes.

5-79. Task: Evaluate a Casualty (081-831-1000).

• Conditions: You have a casualty who has signs and/or symptoms of an injury.

• Standards: Evaluated the casualty following the correct sequence. All injuries and /or conditions were identified. The casualty was immobilized if a neck or back injury is suspected.

5-80. Task: Perform First Aid for Nerve Agent Injury (081-831-1044).

• Conditions: You and your unit have come under a chemical attack. You are wearing protective overgarments and/or mask, or they are immediately available. There are casualties with nerve agent injuries. Necessary materials and equipment: chemical protective gloves, overgarments, overboots, protective mask and hood, mask carrier, and nerve agent antidote autoinjectors. The casualty has the following:

Three antidote treatment, nerve agent, autoinjectors (ATNAA) and one convulsant antidote for nerve agents (CANA) autoinjector.

Three antidote treatment, nerve agent, autoinjectors (ATNAA) and one convulsant antidote for nerve agents (CANA) autoinjector.

OR three sets of MARK I nerve agent antidote autoinjectors.

OR three sets of MARK I nerve agent antidote autoinjectors.

• Standards: Administered correctly the antidote to self or administered three sets of MARK I nerve agent antidote autoinjectors or three ATNAAs followed by the CANA to a buddy following the correct sequence. Take appropriate action to react to the chemical hazard and treat yourself for nerve agent poisoning following the correct sequence.

5-81. Task: React to Indirect Fire While Dismounted (071-326-0510).

• Conditions: You are a member (without leadership responsibilities) of a section, squad or team. You are either in a defensive position or moving on foot. You hear incoming rounds, shells exploding or passing overhead, or someone shouting “incoming!”

• Standards: React to each situation by shouting “incoming,” following the leaders direction if available and taking or maintaining cover.

5-82. Task: React to Direct Fire While Mounted (071-410-0002).

• Conditions: In a combat environment, given a tracked/wheeled vehicle and a requirement to react to direct fire.

• Standards: The vehicle has returned fire and taken appropriate action after analysis of the situation based on an order received from the chain of command.

5-83. Task: Select Temporary Fighting Positions (071-326-0513).

• Conditions: You must select a temporary fighting position, when at an overwatch position, after initial movement into a tentative defensive position, at a halt during movement, or upon receiving direct fire.

• Standards: Select a firing position that protected you from the enemy observation and fire, and allowed you to place effective fire on enemy positions without exposing most of your head and body.

OPPORTUNITY TRAINING

5-84. Opportunity training is the conduct of pre-selected, prepared instruction on critical tasks that require little explanation. Sometimes called “hip-pocket” training, it is conducted when proficiency has been reached on the scheduled primary training task and time is available. Unscheduled breaks in exercises or assembly area operations, or while waiting for transportation, provide time for opportunity training.

5-85. Creative, aggressive leaders and soldiers use this time to sustain skills. For example, a Bradley Stinger Fighting Vehicle commander might conduct opportunity training on aircraft identification while waiting to have his crew’s multiple integrated laser engagement system (MILES) re-keyed during an (FTX). Good leader books are necessary to select tasks for quality opportunity training.

5-86. Leaders, especially NCOs who are first line supervisors, must be prepared to present these impromptu classes at any opportunity. Any time the squad leader has five minutes, he should also be prepared to instruct squad members on subjects such as safety, personal hygiene, or maintenance of equipment. In addition, most junior enlisted soldiers are very capable of preparing and giving short blocks of instruction on Skill Level 1 individual tasks.

DRILLS

5-87. Drills provide small units standard procedures for building strong, aggressive units. A unit’s ability to accomplish its mission depends on soldiers, leaders, and units executing key actions quickly. All soldiers and their leaders must understand their immediate reaction to enemy contact. They must also understand squad or platoon follow-up actions to maintain momentum and offensive spirit on the battlefield. Drills are actions in situations requiring instantaneous response. Soldiers must execute drills instinctively. This results from continual practice and rehearsals.

5-88. Drills provide standardized actions that link soldier and collective tasks at platoon level and below. At company and above, integration of systems and synchronization demand an analysis of mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops, time available, civil consideration (METT-TC). Standard tactics, techniques and procedures (TTP) help to speed the decision and action cycle of units above platoon level, but they are not drills. There are two types of drills—battle drills and crew drills.

5-89. A battle drill is a collective action rapidly executed without applying a deliberate decision-making process. The following are characteristics of battle drills:

• They require minimal leader orders to accomplish and are standard throughout the Army.

• They continue sequential actions that are vital to success in combat or critical to preserving life.

• They apply to platoon or smaller units.

• They are trained responses to enemy actions or leader’s orders.

• They represent mental steps followed for offensive and defensive actions in training and combat.

5-90. Crew drill is a collective action that the crew of a weapon or system must perform to employ the weapon or equipment. This action is a trained response to a given stimulus, such as a leader order or the status of the weapon or equipment. Like a battle drill, a crew drill requires minimal leader orders to accomplish and is standard throughout the Army.

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION

5-91. Every soldier must protect the environment from damage when conducting or participating in training. This means you personally must know and take actions necessary to prevent that damage. Task performance information, such as that in the STPs, identify environmental considerations that you must take into account when performing the task. Technical manuals and other how-to books also contain information. You can also ask your leader for information and advice.

5-92. The Army has made great progress in protecting the environment while conducting productive training. It is not just the protection of wildlife or vegetation that is of concern to the Army. Many installations have sites of archaeological significance and others restrict vehicular traffic to prevent excessive soil erosion. The reason for these restrictions is to preserve the environment for future Americans.

SAFETY

5-93. Every soldier is responsible to ensure realistic training is safe; safety awareness protects combat power. Historically, more casualties occur in combat due to accidents than from enemy action. Ensuring that realistic training is safe instills the awareness that will save lives in combat. Conducting realistic training is challenging business. The goal of the chain of command is not training first nor safety first, but training safely.

Units that participate in tough, well-disciplined training, with technically and tactically competent leaders present, have significantly fewer accidents.

BG James E. Simmons, Director of Army Safety

5-94. The commander is the unit safety officer. He is ultimately responsible for unit safety; however; every soldier is responsible for safe training. This includes leaders throughout the chain of command and the NCO support channel, not just range safety officers and NCOs, observer controllers (OCs), and soldiers conducting training. Well-trained junior enlisted soldiers are often the first to observe unsafe actions or conditions.

5-95. Safety does not mean we won’t perform tasks or missions that carry some amount of risk. In fact, safe training requires recognition of the risk involved, determining the degree of risk and then applying effort to reduce the risk while accomplishing the mission. This process is risk management, and is a key part of planning all training and operations. The result of this process is that soldiers are aware of potential safety problems in a task or mission but also know that leaders have taken steps to reduce or eliminate the effects of those problems.

5-96. The purpose of training is to prepare you and your unit to accomplish missions in combat or other operations. Combat is an environment that will push you to your physical and emotional limits—and beyond. Fear, fatigue, pressure to accomplish the mission and other factors combine to raise stress to seemingly unbearable levels. That stress could cause soldiers to exhibit unusual behavior in combat. Combat stress behavior is the generic term that covers the full range of behaviors in combat, from behaviors that are highly positive to those that are totally negative. Keep in mind that such stress can occur in the combat-like conditions of operations other than war, also. There is nothing wrong in experiencing combat stress or exhibiting the resulting reactions, as long it does not include misconduct.

5-97. Positive combat stress behaviors include heightened alertness, strength, endurance, and tolerance to discomfort. Examples of positive combat stress behaviors include the strong personal bonding between combat soldiers and the pride and self-identification that they develop with the unit’s history and mission. These provide unit cohesion, the binding force that keeps soldiers together and performing the mission in spite of danger and death. The ultimate positive combat stress behaviors are acts of extreme courage and action involving almost unbelievable strength. They may even involve deliberate self-sacrifice.

5-98. The citations for recipients of the Medal of Honor or other awards for valor in battle describe almost unbelievable feats of courage, strength, and endurance. The recipient overcame the paralysis of fear, and in some cases, also called forth muscle strength far beyond what he had ever used before. He may have persevered in spite of wounds that would normally be so painful as to be disabling. Some of these heroes willingly sacrificed their lives for the sake of their buddies.

5-99. Positive combat stress behaviors and misconduct stress behaviors are to some extent a double-edged sword. The same physiological and psychological processes that result in heroic bravery in one situation can produce criminal acts such as atrocities against enemy prisoners or civilians in another. Stress may drag the sword down in the direction of the misconduct edge, while sound, moral leadership and military training and discipline must direct it upward toward the positive behaviors.

5-100. Examples of misconduct stress behaviors range from minor breaches of unit orders or regulations to serious violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). Misconduct stress behaviors are most likely to occur in poorly trained and undisciplined soldiers. But these behaviors can possibly occur in good, even heroic soldiers under extreme combat stress. Misconduct stress behavior can be prevented by stress control measures, but once serious misconduct has occurred, it must be punished to prevent further erosion of discipline. Combat stress, even with heroic combat performance, cannot justify criminal misconduct.

5-101. Combat stress reaction is common, predictable, negative, emotional and physical reaction of normal soldiers to the abnormal stressors of combat. By definition, any such reactions interfere with mission performance or well being but can be treated. These reactions do not include misconduct stress behaviors. They range from fear, anxiety and depression in minor cases to memory loss, physical impairment and even hallucinations in the more severe cases. On the lower end of the scale the behaviors are normal and common signs. As behaviors become progressively more severe in their effects they are warning signs of serious problems. Warning signs deserve immediate attention by the leader, medic, or buddy to prevent potential harm to the soldier, others, or the mission.

5-102. Warning signs do not necessarily mean the soldier must be relieved of duty or evacuated if they respond quickly to helping actions. However, soldiers may need evaluation at medical treatment facilities to rule out other physical or mental illness. If combat stress reaction persists and makes the soldier unable to perform duties reliably, then further treatment such as by specialized combat stress control teams, may be necessary. But prompt treatment close to the soldier’s unit provides the best potential for returning the soldier to duty.

Just because you’re trained for something doesn’t mean you’re prepared for it.

Anonymous

5-103. No training will completely prepare you for combat, but with proper training, discipline and unit cohesion you will be able to do your job and function as a member of the team. Stress in combat is unavoidable, but you can minimize combat stress reaction by continuing to do your job and talking to your fellow soldiers and leaders. Remember that your buddies are under the same stress. They experience many of the same feelings as you do so just talking about it can help them, too. Previous combat experience does not immunize a soldier from the effects of combat stress, either. For more information about the causes, effects, and treatment of combat stress, see FM 6-22.5, Combat Stress.

SECTION III: FORCE PROTECTION

5-104. The operational environment demands that all soldiers are proficient in certain combat tasks. This environment does not have rear areas that are free of enemy interference. We must expect and plan for a potential adversary to oppose Army operations from deployment to the conclusion of the fight, and beyond. For this reason it is vitally important soldiers take positive steps in force protection to minimize vulnerability to terrorist acts.

5-105. Force protection is action taken to prevent or mitigate hostile actions against Department of Defense (DOD) personnel (to include family members), resources, facilities, and critical information. These actions conserve the force’s fighting potential so it can be applied at the decisive time and place, and incorporates the coordinated and synchronized offensive and defensive measures to enable the effective employment of the joint force while degrading opportunities for the enemy.

A Military Police soldier inspects a vehicle entering an Army installation.

5-106. Force protection is a security program to protect soldiers, civilian employees, family members, information, equipment, and facilities in all location and situations. This is accomplished through a combination of antiterrorism, physical security, and information operations; high-risk personnel security; and law enforcement operations, all supported by foreign intelligence, counter intelligence, and other security programs.

5-107. Force Protection does not include actions to defeat the enemy or protect against accidents, weather, or disease. The goal is to protect soldiers, DA civilians, their family members, facilities, information, and other material resources from terrorism. The objectives of force protection are to deter incidents, employ countermeasures, mitigate effects, and to recover from an incident.

5-108. The scope of force protection includes pre-incident, incident, and post-incident task and activities. The achievement of a comprehensive program requires that the full cycle of planning, preparation, execution, and continuous assessment be accomplished before, during, and after the threat event. A complete force protection operation crosses the entire spectrum from pre-incident to post-incident. Force protection is everyone’s business. Be vigilant!

5-109. Standard descriptions of force protection requirements and states of readiness are called force protection conditions. There are five force protection condition levels: Normal and ALPHA through DELTA. Each has specified force protection tasks or security measures listed in AR 525-13, Antiterrorism. Army installations supplement these with specific actions for that installation. Force protection conditions are usually set by Army major commands but may be altered by installation or local commanders, based on local conditions, with higher approval.

5-110. How units conduct force protection may be different in a combat environment only in the specific tasks performed. Regardless of location or activity, the operational environment requires force protection awareness throughout the Army. It doesn’t matter whether you are moving, resting or actually fighting. Be alert for indications of terrorist activity or surveillance and anything that seems out of place.

TERRORISM

5-111. Terrorism is the calculated use of unlawful violence or threat of unlawful violence to instill fear; intended to coerce or to intimidate governments or societies in the pursuit of goals that are generally political, religious, or ideological. Terrorism has four key elements:

• It is premeditated—planned in advance rather than an impulsive act.

• It is political—designed to change the existing political order.

• It is usually aimed at civilians—not at combat-ready troops.

• It is carried out by subnational groups—not by the army of a country.

5-112. Every soldier has some role in fighting terrorism. Usually these are actions in an installation or unit antiterrorism (AT) plan. As a minimum, you should know what the likely terrorist threat is for your area. You should know who to call if you see or hear something that “isn’t quite right.” What would that be? Something that appears out of place: for example, a van parked across the street from an entry control point that reappears at the same time for several days. Reporting such unusual activity may seem an overreaction but is prudent. If it is an innocent citizen who just happened to be there by coincidence, no harm done. But if it was something more, then you may have saved lives. Remember when reporting, just like in giving a spot report by the SALUTE or SALT format, be accurate and as detailed as possible without adding any speculation.

6th Battalion, 52d ADA deployed in early 1996 to Southwest Asia (SWA) on a scheduled theater missile defense rotation. The unit was trained and evaluated in all facets of its mission and well prepared for it, but no more so than any other unit. Weeks passed, force protection condition (FPCON) levels fluctuated, and soldiers were tested time and time again. Staying focused was the watchword. Everything was clicking, and the unit was like a boxer getting instructions from the referee. The referee tells you to break from the tie-up but protect yourself at all times. Boxers have gotten knocked out on the break.

By the early summer of 1996, the battalion’s rotation was coming to a close. Months of ups and downs in FPCON levels didn’t break this disciplined, confident unit’s morale. But at 2230 on the night of 25 June 1996, an explosion sent everyone in the Khobar Towers complex scrambling. Some scrambled for their lives and others to tend the numerous wounded. A large bomb had detonated just outside of the cantonment area, destroying and damaging buildings and sending window glass throughout the compound. Nineteen US Air Force airmen died and hundreds were injured.

But the combat lifesavers and medics of Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 6-52 ADA quickly transitioned to their wartime mission. That mission was to help save lives by "evaluating casualties" and treating and caring for the wounded. But "treat mass casualties," a task performed so well by the unit on its external evaluation, was no longer a training task. It was real. Competence and confidence showed on the stern faces of the soldiers as they and others carefully looked through the debris for survivors to evaluate, treat, and evacuate from the horrible scene. A long day consequently turned into a very long night. Soldiers and airmen worked together as if they had been training for years and everyone did more than his or her part. Guard shifts doubled and sometimes tripled to ensure security was complete.

Later, SGT David Skinner, a combat medic for the battalion, was asked if he was afraid of the possibility of another bomb going off. "You didn’t have time to think about another bomb. We get paid to save lives and that’s what we tried to do." He praised the courage and dedication of the combat lifesavers that stood side by side with the medics. For the actions of the soldiers that night and through the next early morning hours, 6-52 ADA received the Army Superior Unit Award.

5-113. Level I antiterrorism training is required for all soldiers and DA civilians. Army Regulation 525-13 and Department of Defense Instruction 2000.16, DOD Antiterrorism Standards require this annual training. You can accomplish this training online using the DOD Antiterrorism Training System at http://at-awareness.org. Soldiers and DACs traveling outside the 50 United States, its territories and possessions for any reason must have an AOR update within two months of travel. Military and DAC family members must receive antiterrorism awareness training within 12 months of travel, on official orders, outside the US, its territories and possessions.

5-114. The purpose of the annual antiterrorism training is to increase your awareness of terrorism and to improve your ability to apply personal protective measures. The training includes the following subjects:

• Terrorist operations.

• Individual protective measures.

• Terrorist surveillance techniques.

• Improvised explosive device (IED) attacks.

• Kidnapping and hostage survival.

• Explanation of terrorism threat levels and Force Protection Condition (FPCON) system.

5-115. You may also receive antiterrorism training from a certified Level II antiterrorism instructor. The Army’s goal is that all personnel are aware of the terrorist threat and adequately trained in the application of protective measures. Antiterrorism training should also be integrated into unit collective training at every opportunity.

5-116. You, your family, or your neighborhood may be terrorist targets; therefore, be prepared to alter your routine to disrupt surveillance. You should know where to go if communications are disrupted. Your installation and unit should have a force protection and antiterrorism plan. In these plans are instructions for implementing higher levels of security and what individual soldiers should be aware of. These plans also inform soldiers and DACs of where to go in the event of an attack or emergency and provide guidance on protecting family members and visitors on the installation. Critical tasks of installation plans include the following:

• Collect, analyze, and disseminate threat information.

• Increase antiterrorism in every soldier, civilian, and family member.

• Maintain installation defenses in accordance with force protection conditions (FPCON).

• Conduct exercises and evaluate/assess antiterrorism plans.

RULES OF ENGAGEMENT AND RULES FOR THE USE OF FORCE

5-117. Rules of engagements (ROE), rules for the use of force (RUF) and the general orders help soldiers know how to react in difficult situations before they arise. The ROE are directives that describe the circumstances and limitations for military forces to start or continue combat engagement with other forces.

5-118. The ROE are normally part of every operations plan (OPLAN) and operations order (OPORD). The ROE help you in obeying the law of war and help prevent escalating a conflict. Know the ROE and actively determine if any changes to the ROE have occurred. The ROE will be different with each operation, in different areas, and will change as the situation changes. In no case, however, will the ROE limit your inherent right to self defense.

5-119. A thorough understanding of the specific ROE gives soldiers confidence that they can and will react properly in the event of an attack or encounter with local personnel. Confident soldiers do not hesitate to properly defend themselves and their fellow soldiers. Likewise, confident, disciplined soldiers will not take action that violates the ROE. In both cases, confident soldiers protect lives and demonstrate professionalism, both of which have positive effects on the local population and for the overall Army mission.

Rules of Engagement

Company D, 1st Battalion, 41st Infantry, was assigned to Task Force Eagle as part of Operation Joint Endeavor. Power struggles taking place in Republika Srpsk sparked violent clashes in northeastern Bosnia-Herzegovina. One such clash involved D Company.

On 5 September 1997, about 110 angry Serbs boxed in 60 soldiers from D Company, guarding a checkpoint in Celopek, north of Zvornick. Twenty-five of the US soldiers faced 70 Serbs to the south of the checkpoint, while another 25 faced 40 Serbs to the north. The angry Serbs, throwing rocks, bottles, and light fixtures, punched at least three of D Company’s soldiers and attempted to drive vehicles through the roadblock. At one point, as an automobile attempted to break through, the crowd surged forward. The soldiers, well disciplined through rigorous training and armed with a thorough understanding of the ROE, held their ground and focused on the mission. The crowd finally backed off after an hour and a half when the commander ordered his troops to load their weapons and the Serb police arrived to assist.

The soldiers of D Company accomplished their mission while displaying enormous restraint—the result of the discipline that had been strengthened in their training. But for that discipline and confidence, the incident might well have resulted in disaster, not only for the soldiers, but also for the diplomatic mission they were assigned to enforce. They were confident in the training they had conducted prior to and during deployment and in their leadership. Their discipline in adhering to the ROE allowed them to diffuse the situation using appropriate force and resulted in the protection of the unit, the soldiers, and the civilians.

5-120. A useful acronym for remembering some of the basics of the ROE is RAMP.

• R—Return Fire with Aimed Fire. Return force with force. You always have the right to repel hostile acts with necessary force.

• A—Anticipate Attack. Use force if, but only if, you see clear indicators of hostile intent.

• M—Measure the amount of Force that you use, if time and circumstances permit. Use only the amount of force necessary to protect lives and accomplish the mission.

• P—Protect with deadly force only human life, and property designated by your commander. Stop short of deadly force when protecting other property.

5-121. Rules on the use of force are escalating rules for US military personnel performing security duties within the United States. Like the ROE, RUF may vary depending on the operation and location, so be sure to understand the RUF. These rules primarily limit the use of deadly force to specifically defined situations. You have the inherent right of self-defense and the defense of others against deadly force. But use only the minimum force necessary to remove the threat. Deadly force is only used as the last resort, typically as follows:

• For immediate threat of death or serious bodily injury to self or others.

• For defense of persons under protection.

• To prevent theft, damage, or destruction of firearms, ammunition, explosives, or property designated vital to national security.

5-122. When the situation permits, security personnel utilize escalating degrees of force. The degrees are defined as follows:

• SHOUT—verbal warning to halt.

• SHOVE—nonlethal physical force.

• SHOW—intent to use weapon.

• SHOOT—deliberately aimed shots until threat no longer exists.

• Warning shots are not permitted.

5-123. Your training should include ROE or RUF. This should include classroom type instruction that states what the rules are but also should be a part of field training. For example, a field exercise could include situations training soldiers on what to do if a large group of local civilians appear outside the unit perimeter. In this way, soldiers can gain experience in handling potentially hostile crowds while complying with the ROE.

Guard Duty

5-124. We can’t leave the subject of ROE and RUF without a word on guard duty. Guard duty is important. It is a mission common to tactical and garrison operations and key to physical and operational security. It is also important in antiterrorism. A sentinel at a guard post is protecting his fellow soldiers and may be the first line of defense against enemy soldiers, thieves, spies, or even terrorists. It is for these reasons you should take guard duty seriously and approach it with the same professionalism that you do all your other duties. The General Orders are:

• General Order Number 1: I will guard everything within the limits of my post and quit my post only when properly relieved.

• General Order Number 2: I will obey my special orders and perform all my duties in a military manner.

• General Order Number 3: I will report all violations of my special orders, emergencies, and anything not covered in my instructions to the commander of relief.

THE MEDIA

5-125. While not directly a part of force protection, interaction with the media has an impact because potential adversaries can get useful information about you, your unit, your mission, or even your family through news reports. Commanders will implement operational and information security programs to defeat terrorists’ efforts to gain information, but in nearly every case, such programs involve knowledgeable and positive action on the part of individual soldiers.

5-126. The media, that is, the civilian news gathering organizations of the world, have a job to do—report what they see to the world. There are times when the media will be interested in your unit or your family members. Deployments and reunions are always newsworthy events that will attract press attention, and so will gate closures or reports of casualties. But every operation and every installation has specific guidance for speaking with the media. That guidance will tell you what are appropriate or inappropriate subjects to comment on and is intended to help you maintain operational security. In any case, you should have your commander’s authorization to speak with a member of the media before doing so, particularly when the topic relates to the Army or the Department of Defense.

5-127. The military as an institution and the media have had their ups and downs, but the rapport between individual soldiers and members of the media has almost always been excellent and you should do your best to keep that up. America benefits from a well-informed public. While you do not have to speak if you do not feel comfortable, if you do communicate with someone from the media, keep the following general rules in mind: