CHAPTER 3

GROUND ZERO

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place?

— HORACE SMITH

The word trespass has far more ethical meaning than it deserves. Simply by erecting a sign saying ‘Do Not Enter’, the state or the corporation puts into your mind the idea of transgression. Go through that broken gate, squeeze your way through that gap in the builder’s fence, stride confidently past a momentarily empty security office and you become a sort of moral outlaw. But a ‘Do Not Enter’ sign might also alert you to something someone else doesn’t want you to know about.

The Endeavour Hills Secondary College was once called Doveton North Technical School. It opened in 1969 to train boys to do the jobs of their fathers by preparing them for apprenticeships – or at least for the discipline of the time clock – at the Big Three. My friend Dave, with whom I used to open the batting, went here. Today, it’s the sort of place the economic reformers don’t want you to see. Here is the epicentre of creative destruction, the Ground Zero of Professor Schumpeter’s dark vision.

The first thing you notice as you enter the school today – which you do by bending double to pass though a hole smashed in one of its doors – is the unnerving crunch of broken glass under your feet. In retrospect, it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, since the desolate playground is littered with unwanted mattresses, paint tins and other hard-to-dispose-of rubbish. Still, nothing can prepare you for what’s to come, especially when you think to yourself that this is Australia, not some American city like Detroit where people don’t really count.

In the early 1980s, when Ronald Reagan was deploying cruise missiles on the borders of the Soviet Union, a new genre of movie appeared, set in the nuclear Armageddon. You might remember some examples: Threads, The Day After, When the Wind Blows. The most disturbing thing about these movies wasn’t the physical destruction they showed but their belief that a post-nuclear society would descend into some sort of chaotic lunacy, a kingdom of the insane brought under control by a modern version of feudalism, ruled by street gangs.

Perhaps because I was fascinated by these films (a fascination which started when a teacher at Doveton High showed us Peter Watkins’ then shocking mock documentary, The War Game), the first word that comes to my mind as I enter the school building and stare down the main corridor is apocalypse. Down all four corridors of the main block – which consists of three parallel chambers about fifty metres long, connected mid-section by a shorter fourth one – every wall has been defaced by the warnings of street gangs, and literally every panel of glass smashed. Between elaborately painted tags, there are the usual obscenities and crude symbols of people being hung by the neck. In almost every classroom the walls have been roughly removed, as if some army of psychopathic home renovators had set to them with long-handled hammers. Here and there floorboards have been ripped up, the better to get to the copper wires and the recently installed fibre-optic cabling. In one of the central courtyards, a large, twisted pile of coloured tubing of various diameters is evidence of the building’s nocturnal disembowelling; perhaps there’s money in it.

Particular attention has been paid to the entrance hall, which looks like a high-street bank frontage that has been ram-raided by a truck. Next to it is a large yellow arrow, possibly put there to manage the traffic when the place was still alive with the shouts and movement of teenagers. Over the arrow, some illegal visitor – who knows, perhaps a grammatically challenged former student, now unemployed – has spray-painted the words ‘IF U WANT 2 DIE, THIS WAY, FUCKERS!’ (I’ve added the commas to make the meaning clear.) It’s not as pleasant as the slogans about flagstones and beaches the Parisian students wrote on the walls of the Sorbonne in 1968 but it’s rather more direct. In one classroom, the day’s lesson – on how to make a rebate joint, a skill that could help some youngster get a job in the building trade – is still in chalk on the blackboard.

The entrance hall – after the apocalypse …

A classroom – newly renovated …

A slogan for Professor Schumpeter …

Lessons for us all …

Perhaps the strangest thing about the insides of the now destroyed school is the feeling of newness. Between the holes and the graffiti and under the broken glass and cables, everything is in nearly mint condition. There appears to have been a very recent and major fit-out, leaving behind new classroom partitions, pristine whiteboards, rows of shattered toilets that are still sparkling white, walls yet to be turned grubby by the rubbing of teenage shoulders, and carpet not yet muddied by dirty shoes. It’s as if the whole place was scrubbed clean for its execution, like a sacrificial infant at the temple of a Mayan sun god.

Disembowelment …

The insides of this dying building are so breathtaking that they induce in me a variety of blood-pumping excitement; after all, it’s not impossible, and perhaps even not unlikely, that some ice-crazed adolescent might appear around a corner at any moment with a knife. It’s only when I crawl outside again that my sense of melancholy returns. There, in front of me, is an old soccer field, the grandstand burnt down and razed by council bulldozers as a safety precaution, the pitch alternately bare and weedy. Behind the main building is the vocational education block, similarly smashed and defaced. They once taught young people skills for the auto trades here; now, having decided to leave car manufacturing jobs to the Germans, French, English, Koreans, Thais and Chinese, we can safely leave public assets like this in ruins. At least the economists will be happy, because the otherwise unused land is now being put to the most efficient use their collective wisdom has been able to devise: as a junkyard.

As I walk away from the school, scale its fence and look back, I notice that it is slowly being overtaken by nature. Weeds sprout from every garden bed, concrete crack and gutter like those reclaiming the Roman forum in the famous etchings by Piranesi. Parts of the roof are disappearing; whether blown off or stolen it’s hard to tell. Soon the rain will be getting in, the walls will be getting damp and the place will be unsafe to enter. If you’ve ever read John Wyndham’s classic novel The Day of the Triffids, you’ll know that its best scene is the one where the protagonist travels back to London years after the apocalypse, only to find it reclaimed by nature, its pavements choked by spreading weeds, turf growing on roofs, tree roots undermining buildings and branches poking through smashed windows. That’s Doveton North Tech today, once proud but now an abandoned ruin, slowly disappearing beneath nature’s onslaughts.

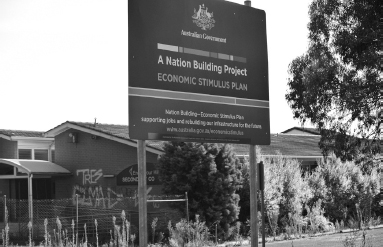

There is, however, one surface in the complex that remains untouched by the hands of the vandals. It is the sign boasting that the now completely wrecked and abandoned school received money from the stimulus plan that followed the global financial crisis. ‘Nation Building – Economic Stimulus Plan,’ it reads, in the sort of dubious English that the managerialists who devised the plan love so much, ‘supporting jobs and rebuilding our infrastructure for the future.’ It seems the school had been given a major renovation and refit just before it was closed.

A nation-building project …

Here is the Building the Education Revolution plan at work. Its inspiration, John Maynard Keynes, once said that in a recession the most rational thing to do is pay people to bury sacks full of pound notes in disused mineshafts, and then pay the same people to dig them up again. This could have been the sort of thing he meant. Having read that morning in the Financial Review that the market for collateralised debt obligations is once again booming, I muse that perhaps when the next financial crisis comes we can dig up the buried foundations of this school as yet another Keynesian make-work project.

While I’m taking photographs of the sign, a Vietnamese-Australian couple pull up in their car, taking me (again in my fluoro vest and hardhat) for a council employee. When is the council going to sell the site, they ask, because they want to buy the land and build apartments on it. I tell them I have no idea, but that some of my friends went to school here and it’s still owned by the Department of Education, and everyone knows they move at a snail’s pace. Might be years! They leave disappointed.

The strange fact that the sign remains seems a symbol of something important, although it’s not easy to say precisely what. A bureaucratic stuff-up, perhaps? Evidence, maybe, that the bureaucrats who closed the school have a strong sense of irony? Or proof that, when it all comes down to it, no one really cares what happens in Doveton, and that the destruction of places like this doesn’t even count as a source of political embarrassment? That’s my guess. What we do know is that the government public-relations expert who once commanded the sign to be raised couldn’t even be bothered to order it taken down.

I take one last look at the sign before driving off to another abandoned school site – this time my old primary school, which is in a similar state of neglect. To my surprise, I find it surrounded by a three-metre-high fence, which must have been erected after I exposed the school’s scandalous state in the national press the year before. I later take Panda back to it, and we walk across the remains of the old adventure playground where we first became friends. He tells me that at least people are listening, even if the only effect has been to encourage officials to try to hide the place from view.

As I scale the old school gate to cross the road to have a look at my cousins’ old house – which is in a state almost as shocking as that of my own old family home – I look back to the school and think of Shelley and his romantic poet friends who had something to tell us about forgotten civilisations. Around the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands of official indifference stretch far away.

If a picture paints a thousand words, then the image of a shuttered shop is an essay in social decline. You can see the shutters by day, up high, wound around their covered rollers like aluminium foil in its cardboard box. But at night they come down with a rattle and a thump, in a noisy indictment of a society that has gone wrong.

There are no shutters above the frontages in the wealthier shopping strips, despite there being a lot more to steal; go to Albert Park, for example, and you won’t see them at all. (For this we can thank supply-side economics, which helpfully supplies depressed neighbourhoods with necessary numbers of the young, the unemployed, the drug-addicted and the idle.)

And from memory there were no shutters in our shopping strip when I was a child. It’s five minutes’ walk from my old street, and about three from my primary school. My mother worked on the cash register in the milk bar; it must have been before 1972, when she started at Heinz. Walking back into the milk bar now evokes the strangest feeling, because while it has changed completely, it has yet remained completely unchanged.

I remember the glass counters full of stock of all descriptions – lollies which we used to buy in five-cent mixed bags, tea, coffee, biscuits, cakes, breakfast cereals, cheese and cold meats. There was a big metal meat slicer, from which my mother would produce slithers of sweet ham or continental sausage into our palms when the shop’s owner wasn’t looking. A large freezer contained Peters and Streets ice creams, and cheap toys stood on the shelves on the wall behind the counter, which Mum would occasionally buy for us as small treats. It was never a fashionable delicatessen; perhaps closer to a bright and cheery 7-Eleven. But now …

The best word I can use to describe the old milk bar now is poor – in the economic sense. Looking around, it seems not a lick of paint has touched its walls for half a century. My guess is that the only thing in the place that has been replaced is the refrigerator – which was probably made in China. The floor, then brightly coloured concrete, adorned with painted footprints advertising a now defunct childhood confectionary, has been discoloured and worn down in the places of highest traffic, like the stone floors in ancient churches. The almost empty shelves are watched over by a proprietor who, I guess from the kitchen-like smells of the place, might live out the back.

On my first visit back to the shop I get chatting to the cashier. I figure she’s most likely the proprietor, as it’s hard to see how any shop as poor as this could possibly support a living wage; it has to be family-run. I tell her how my mother once worked here, and how I haven’t been into the shop for about thirty years. When I say the shop hasn’t changed much, she tells me in return that the neighbourhood has changed enormously over that time. It’s no longer safe, she said, and I should be careful walking around, even though it’s only mid-morning.

As I walk down the strip and drink my Coke, I see a policeman photographing the smashed window of one of the adjoining stores. A young man with the broken physique one normally associates with severe addiction approaches me for a strange conversation about daytime television; he soon walks off, carrying a six-pack of pre-mixed drinks. The danger seems more comic than scary; I can’t imagine feeling afraid in a place like this, where I’d felt so safe as a child, but then I don’t live there anymore. And the cause of rational fear is, after all, cumulative negative experience.

The next time I come back, a year later, the shop has changed completely. Not the décor, which is still untouched, but the food shelves, whose contents have been replaced by the cheapest junk from the crummiest factories in the world. The milk bar is now a mixed business, part milk bar, part plastic junk from Bangladesh or China. Outside, a lonely sandwich board stands on the footpath, looking like it has been painted by a child. It reads: ‘$2 Shop.’

At least there’s only one $2 shop here. At the bigger shopping strip on the other side of Doveton I count three of them, plus a charity store run by one of the bigger welfare agencies. I recognised one of the $2 shops as the baby and children’s clothing store that my aunt, Anna, had run back in the late 1960s and early ’70s. The clothes she sold would almost certainly have been produced here in Australia. A lot of my and my sisters’ childhood clothes came from there, made by women working in factories in Melbourne’s northern suburbs.

That thought reminded me of a conversation with another aunt, Ena (one of Arthur Calwell’s original beautiful blonde Baltic refugees who came here in the late 1940s), who told me how, when she worked as a salesgirl in the Dandenong Coles Variety Store back in the mid-1960s, she used to sell the very garments that her mother had stitched in a clothing factory in Bendigo. Thank God such things as clothes are all now made in Bangladesh, because the law of comparative advantage tells us clearly that there’s no need for us to make them here, and it would be a sin to contradict the law of comparative advantage.

At the end of the strip is a real-estate agent’s office that used to be a branch of the Commonwealth Bank. In its window there is a listing for one of the shops, a rather well-presented fruit and vegetable store, for sale to bids over $50,000. A whole double-fronted shop, with two car spaces, going for just north of fifty grand? In the inner city, just renovating a café or a restaurant might set you back a million.

The old Doveton Post Office is now owned or leased by some evangelical sect, which, no doubt in addition to undertaking sundry unspecified good works, believes in speaking in tongues, divine healing, a real physical hell and the imminent second coming of Jesus. They also post their BSB and account details on their website in case you want to make an electronic funds transfer to help out with the battle against Satan. Later, I come across a similar church squatting in a vandalised building in a street where an ancient factory once stood and a woman was savagely murdered last year. An economic development officer tells me that evangelical sects have targeted Doveton because of the cheap rents, and that one of the pastors here is infamous for inciting hatred of Muslims.

As I walk around the shopping centre, having bought in one of the $2 shops a $10 soccer ball for my sons (the stitching of which lasts just a few days), I think unkind thoughts about economic reformers. But isn’t it refreshing to know that they have so successfully liberated all of us from the pathetically unsophisticated lives, crummy consumer goods and poverty of our past? The unemployment rate here in Doveton is ten times that of the wealthiest suburbs, and fully two or three times that of some other very proletarian-sounding places. And we’re thirty years into an era of economic reform that was meant to make us all better off!

Then it strikes me: it’s Doveton and other places like it that have paid the price for the gains the rest of country has made. It’s only because places like Doveton are smashed up – their old communities dispersed, their factories closed, their unions broken, their skilled craftsmen forced to work two menial jobs to make ends meet, their political leaders left morally bereft and philosophically rudderless, their youngsters unemployed and drinking before midday, their cheery little corner stores turned into $2 shops, their front yards turned into scrapyards and their schools stripped of the metal from their roofs and the cables from their floors – that everyone else feels so prosperous. It’s because of all the sacrifices that the people of Doveton have involuntarily made that people in more affluent places get to drive their Audis and BMWs, build their schools new campuses in China, send their boys on cricket tours of England and their daughters on gallery expeditions to Paris, make their children the leaders of tomorrow, convert their income to capital and super, rake in franked dividends from their Commonwealth Bank and Telstra shares, shop in New York, own five investment properties, and get their accountants to arrange it all so the taxman – so willing nowadays to turn a blind eye – doesn’t know the half of it. It’s only because Doveton is down that they are up, because Doveton is poor that they are rich, because Doveton has been made to feel inferior that they can feel effortlessly superior. Every coin has a flipside, every gain has a cost; for every winning team there’s a losing one, for every Hawthorn and Point Piper and North Adelaide and Peppermint Grove there’s a Doveton.

By coming to places like Doveton, you see plainly that wealth isn’t just created, it’s distributed, and you understand that the way it’s created determines the way it’s distributed. You see that in order for the economic reformers to unchain the nation, Doveton had to be placed in chains. And it’s time Australia and its leaders owned up to the logic of what they’ve done.

We’re constantly told that this sort of thinking isn’t the way we should go; that it’s ‘class warfare’ and ‘the politics of envy’, and that it seeks to drag others down when the goal is to lift everyone up. But that’s a cheap and easy line and nothing more, because Doveton and places like it remind us that while the economy has been unchained for thirty years, the reformers’ promise of lifting everyone up hasn’t been fulfilled, and places like Doveton have actually gone backwards. If there’s been an outbreak of envy, it’s among the well-off who envy the unemployed for their dole and welfare payments, which they have savagely reduced to help even up the score.

It didn’t have to be this way. We could have modernised differently, with a little more thought for what was going to happen to the people at the bottom, the people for whom our now destroyed old society had been built. The Labor Party, at least, should have thought about this. Now it’s time to choose another way.

Shuttered shops …

Bouncing my ball, I make my way back to my car. I take out my camera and lean on the bonnet, looking over at the shops, hoping to get a shot of the shutters coming down; it’s already after five. But of course for the owners of such shops, the long day doesn’t end at the traditional closing hour.

Something about it all makes me want to rebel, but my sadness is impotent in the face of a decline so profound and irreversible. I can’t reopen the factories and give Cheryl and her workmates back their overtime, or restore my old streets, schools and shopping strips to their former, sunny glory. A writer – even one who is politically well connected like me – can do little except put words in a speech, and those are easily ignored and forgotten, even when spoken by a prime minister. How, I wonder, has it all been allowed to happen without anyone in power saying, ‘Enough’?

The answer is simple: there was a revolution. We just called it something else.