Edie had heard some buzz within the industry that Puritan Fashions, a huge clothing manufacturer, was backing a new store slated to open in a few months. The store was going to be called Paraphernalia, which was a boutique concept very popular in London started by a visionary young man named Paul Young.

Paul’s idea was to set up individual shops within big department stores to give a stable of up-and-coming designers such as Foale and Tuffin, Daniel Hechter, Emanuel Kahn, and Paco Rabanne a platform to sell clothes the likes of which people hadn’t seen before. It was all new, new, new! This is the model used now in all department stores, but Paul was the man who invented it. He was a retail genius and was even responsible for introducing Mary Quant to the American market during his brief stint at J. C. Penney.

Karl Rosen, the man who owned Puritan Fashions, lured Paul to New York City, in hopes that he could work the same magic there. Paul’s specific vision for New York was to cater to young, rich-girl society types and bring downtown uptown. And it wasn’t just for girls: boys could shop there, too . . . as long as they were skinny enough and didn’t mind their buttons and flies on the wrong side.

I had been working for Mademoiselle for nine months when on a Friday morning, Edie approached me to say that Paul had called her asking for names of interesting new designers. I wondered what this had to do with me. I wasn’t a designer, I just made clothes for the girls around the office and for my mail-order gig, but a real designer . . . me? Uh-uh. I certainly didn’t think of myself that way.

She went on to say that she had set up a meeting for me with Paul on the following Monday afternoon. I was shocked and told her, “But that only gives me the weekend to pull it together!”

“Oh,” she replied calmly, “I’m sure you can handle it.”

I didn’t know what to do first. I was already staying up until all hours working to keep up with my orders. How was I supposed to make anything new to show Paul!?

I had no time to waste, so I ran around the office and talked to every girl who had bought something from me. By then I had graduated from making the little crocheted tops to super-simple stretchy little dresses as well. I asked them to bring the clothes they had bought to the office on Monday morning so I could borrow them back for my interview. They were all excited for me and more than happy to help.

When I got home that night, I gathered up all the stuff I had made for myself and was kind of amazed at the amount of clothes. Maybe Edie was on to something. Maybe I was a designer.

I spent the entire weekend redrawing sketches of all the clothing I had made and did new sketches of things I planned to make, all done in crayon, which is how I always worked.

As you can imagine, the weekend passed in a blur. I think I might have slept as much as two hours each night, if I slept at all.

When I got to the office on Monday morning, all the girls whom I had asked to bring in clothes came by and dropped them off at the art department. I’d fold each dress or whatever the garment was neatly and add it to one of the suitcases I had brought in to lug them to Paul’s office.

When lunchtime arrived I was out the door like a shot to make my way to 1400 Broadway, the address Edie had given me. When I ran into her on my way out, she said, “I’d wish you luck, but you don’t need it.” Buoyed by her confidence, I briskly walked all the way to the Puritan offices.

It was an unusually hot day for so early in the summer, and I was sweating when I finally reached my destination. I was wearing one of the dresses I had made myself. It was short but not too short—that would come later. It was also brightly colored but not too bright—that would come later as well. It wasn’t at all crazy, like some of the sketches I had done. I thought it was better to err on the side of conservative . . . or at least my version of what conservative was.

I had just had my hair cut in the Vidal Sassoon style. Not that I could afford to have my hair cut at the salon. I was actually dating a hairdresser from Sassoon who gave me the haircut at his apartment. I remember he used his chrome toaster instead of a mirror to see how he was doing. With my outfit and new do, I thought I was looking every inch the savvy New York designer.

I gazed up at the tall building smack-dab in the middle of the Garment District. Edie had told me that Puritan owned the entire building as well as other buildings in the area. I think she wanted to impress upon me just how huge an organization it was. But I was more intimidated than impressed and wondered again if I really could work as a fashion designer. As intimidating as that possibility was, it was also exciting. It had been quite the crazy year. First the contest, then the eye-opening trip to London, the job at Mademoiselle, and now this interview. I must have had more than one lucky star shining down on me.

I tried not to place too much importance on the interview. I told myself to just do my best and go with the flow. Whatever happens, happens. If it didn’t work out, I’d still have my job at the magazine. Coming back to the moment, I put any negative thoughts out of my head and, holding tightly on to my two hard Samsonite suitcases, strode into the building with as much confidence as I could fake.

When I got up to the twelfth floor, where I had been instructed to meet Paul, I saw that it was an old, run-of-the-mill kind of office, a little shabby even, which surprised me, as I had expected something fancy, stylish, and chic. Oh, boy, did I have a lot to learn about the garment business!

Out of nowhere appeared a secretary, as unglamorous as the office, who led me all the way to the back of the huge, crowded space. I was further surprised to see that this big shot didn’t even have a real office, just a desk and a couple of chairs tucked into a corner between what looked like a mile of rolling racks.

I walked up to his desk and, with my nerves jumping all over the place, said as brightly as I could, “Hi! I’m Betsey.” He looked up from what he was doing, and I saw that he was a good-looking, very unbusinesslike Englishman in his early thirties. But what made more of an impression on me was what he was doing. He had piles of paper on his desk and he was doodling . . . in colored crayon! I felt a connection immediately.

He smiled at me and said, “Edie spoke very highly of you, and I’ve been looking forward to meeting you. Why don’t you show me what you’ve got.”

I heaved my heavy suitcases onto his desk and when I popped them open they practically exploded. Paul started to go through my things, slowly and hesitantly at first, and then more quickly. I convinced myself that he was trying to get through it all in a hurry before asking me to leave. He was completely silent the whole time as I absentmindedly bit my nails.

Finally, after scrutinizing my last drawing, he collapsed exhaustedly into his desk chair, looked up at me, smiled, and said, “When can you start?”

I almost asked “When can I start what?” before I realized what he meant. I was in shock. Just like that he had decided that I was going to be Paraphernalia’s newest designer.

I would later learn that that was the way it was done. Paul’s word was law. He said either yes or no, and that was it. He knew instinctively if something was going to work. There was no long approval process for anything.

When my initial shock wore off, we got down to business. He told me that his plan was to open Paraphernalia in three months and that all of my clothes would have to be delivered by then.

I would be responsible for the design and I was expected to produce the first sample. The Paraphernalia people would be responsible for the actual production, getting my designs into factories and produced. They’d decide how many of each garment would be made, organize deliveries, and so on and so on. Thank God! I would have had no idea how any of that worked.

Then, best of all, he told me that my name would be on the label. It was to read “Designed by Betsey Johnson for Paraphernalia.”

At the time I didn’t have a clue how special and unusual a thing it is to have your name on a label and I want to point this out to all of you design students out there: this is not how it usually works! People slave for years before their name goes on a label.

I wasn’t going to be the only designer. Paul told me he had already hired a few others, and I was dying to meet them. There was a girl named Deanna Litell, who was already kind of established. Her clothes were very bold, very graphic. Lots of black-and-white pieces. The others were Michael Mott, with his military-style clothes, and Diana Dew, who did fabulous electric dresses. Another designer, Joel Schumacher, was only making capes. Incidentally, if this name sounds familiar, it should. This is the same Joel Schumacher who went on to become famous for directing the movies Batman Forever, St. Elmo’s Fire, and The Lost Boys, to name a few.

Paul went on to explain that I would receive very little help from the Paraphernalia organization . . . whatever that actually was. Paul was the only person I was in contact with, and even that contact was spotty. I was to be paid a salary. I don’t recall how much, exactly, but it must have been decent, because I was able to afford a larger apartment.

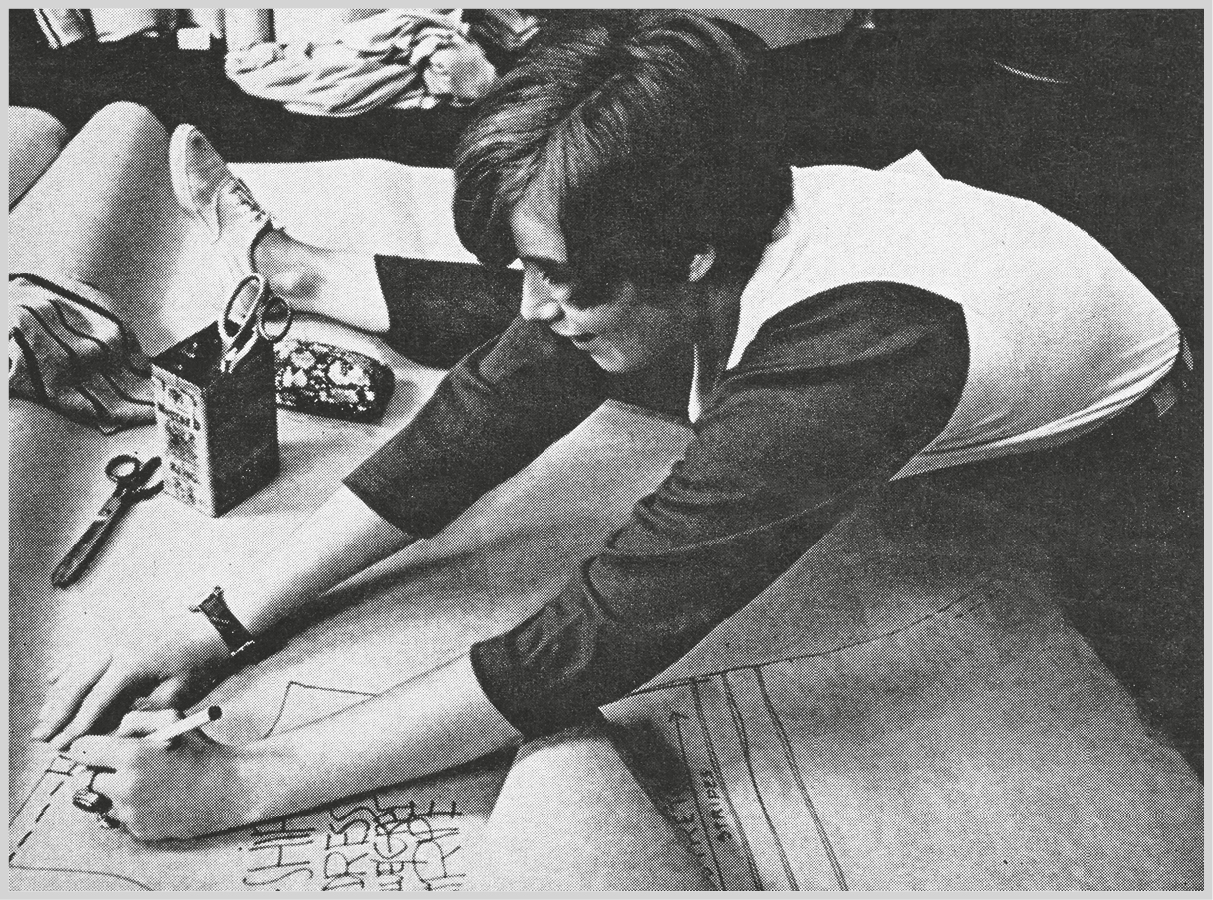

They did set me up with a small workroom in another one of the Puritan buildings and hired me a pattern maker. She was a beautiful hippie-dippie Greek girl named Tulah, who ended up working with me off and on for most of the rest of my career. And thank God for that. Until then I had been winging it—doing patterns my own way, which worked because my dresses at that time were very simple. I’d lie down on the floor on top of the pattern paper and just trace my own body with a crayon. Real pattern making is actually a quite specific skill, and very tricky. You begin by looking at a fashion illustration and interpreting what each of the lines and curves means. You apply these interpretations to a sheet of thin tissue paper and come up with a series of shapes that you cut out, and then you move onto pattern paper, which is more substantial. Then, and only then, do you trace the pattern pieces onto the actual fabric you’ll be using. Whew! I was glad I was going to have someone doing it for me.

Typical me! On the floor in my Paraphernalia workroom.

A trio of my Paraphernalia looks

After spending eight hours in the workroom, most days Tulah and I would continue making the patterns at my apartment at night. I was expected to pay for my samples myself, out of pocket, and get reimbursed later, which I thought was a little odd. In fact, the way they handled the whole business side of things seemed strange. But what did I know? I had nothing to compare it to. I just assumed that was how the garment business was run.

As far as meeting the other designers, I never even saw them, as we were all working in separate locations. Paraphernalia wasn’t run like a big creative lab, but just encouraged each of us to do our own thing. Do what we loved and what we were good at, and maybe keeping us apart was Paul’s way of making sure that each of us did just that. More than likely, judging from Paul’s “office” situation, they just stuck each of us wherever they had the space. I did meet Joel Schumacher once when he stopped by my place to pick up some fabric or something or other from me. All I ever remember Joel making was flamboyant capes.

Without any input from the powers that be, I had to figure out for myself how to get things done. I did reach out to D.J., and with her help I sourced lots of different kinds of fabrics; I designed one dress I called “Silverfish.” It was a basic shift shape made out of silver lamé fishnet. I also found a great faux suede out of which I made something I called my “Story of O” dress. It was a little A-line with large, strategically placed brass grommets sewn into it, exposing your skin underneath.

These would all go on to be hugely popular and great sellers. They even inspired a brilliant ad campaign that included taglines like “Do you dare wear Betsey’s Story of O dress?” or “Do you Silverfish?” But my favorite ad was one that was headlined “Are You Confused Enough for Paraphernalia?” It listed about a dozen insane questions. My favorites were:

“Are you getting obsessively caught up in your Dynel hairpieces?”

The “Story of O” dress and me already doing my splits

“Can you bear the strange din of your Betsey Johnson noise dress?”

“Are you discovering a new crueler you when you wear leather, nail-heads and aluminum?”

“Do you think A Dandy in Aspic should become a summer dish?”

The ads were so hysterical and groundbreaking and so quintessentially sixties. I don’t know who came up with the concept, but Paul Young had the genius to find him or her.

Another early piece I did was something I called the “Julie Christie” dress, which was just my basic T-shirt design to which I added a starched collar and cuffs and little buttons up the front. It wasn’t originally called the Julie Christie, but I dubbed it that when she wore it on the cover of Mademoiselle after she had won the Oscar for her role in the movie Darling. This was huge exposure for me. Julie Christie was the It girl of the moment. The magazine had brought in clothes from a whole bunch of designers, and she chose mine.

The Julie Christie gig wasn’t a fluke. Paul had lots of Hollywood connections as well as New York society ones. In fact, to me it seemed as if there was no one he didn’t know. He even got the French actress Anouk Aimée to ditch the Chanel outfits she was so famous for wearing and switch to mine. Not too shabby! Paul had a way of putting his connections to work . . . literally. He had the genius idea to hire Susan Burden as the store’s manager. Susan was a well-known socialite and good friends with Joan Kennedy, so there were also intriguing political ties.

For the opening of Paraphernalia, I really didn’t have a specific plan. I designed a ton of stuff, but there was no cohesive collection, no color story, no theme. All of my pieces were random one-offs. They were things I loved and believed in and wore myself. And Paul was fine with that.

I had done all of my design work months earlier, made the patterns, and produced the samples, which I handed over to one of Paul’s people to do with what they would, and before I knew it the three months of waiting had flown by. I couldn’t wait to see my designs all in a row on a rack in a store.

Just three days before the opening I got a call from Paul, which was unusual as I hadn’t had much contact with him at all. I’d mostly been dealing with his production people. He sounded upset, and I figured it must be the stress as he was probably going nuts gearing up for what was going to be quite the unique store opening. Paul had taken me on a tour of the unfinished space just one week earlier, and even in its unfinished state I could tell it was going to be unlike any other store people had seen before. It was a big, stark white box with lots of mirrored surfaces and chrome. It was like stepping onto a spaceship or into the future. It was on Madison Avenue at Sixty-Seventh Street, strategically located right next door to Vidal Sassoon—another brilliant move on the part of Paul. He figured after a girl got her hair done she’d want to complete her new look with a new outfit.

I was about to find out that Paul wasn’t suffering from preopening jitters. He laid it on me right away: “Betsey, something got screwed up at the factories. Your clothes will not be ready for the opening. I’m so sorry.” I couldn’t believe it. I had worked really hard and been so looking forward to the big night, and now this. The wind was knocked right out of my sails. I felt as if I had just been punched in the stomach.

Then he asked me if I had anything that I could get into the store. I swallowed hard, not wanting him to know how upset I was. I told him that I had some stuff and that in the next few days I could make a few more pieces. He said something like “Good girl!! I knew I could count on you.” And that made me feel a little better . . . not much, but a little.

When the big night of the opening arrived—September 16, 1965, to be exact—I toyed with the idea of not going. I figured I could use the excuse of my clothes not arriving on time, which was true enough, but the real reason I didn’t want to go was that I couldn’t imagine being in the same room as all of the beautiful models who had been invited. There was talk that even Twiggy was going to be there! I felt that I was way too heavy to be standing next to these types of girls. Also, in spite of my chic Sassoon haircut, I never did quite convince myself that I passed for a hip young fashion designer. I assumed that the other designers for Paraphernalia looked like the models who wore their clothes, but how would I know? Remember, I had never met them.

Of course, in the end I did drag myself to the opening. Luckily, by the time I got there, the store was so jam-packed with people that no one even noticed me. It was every inch the “happening” that Paul had said it would be. He hired Andy Warhol to produce the event, and Warhol in turn got The Velvet Underground to perform. He also got Pattie Boyd, Marisa Berenson, and Jean Shrimpton to walk around the party modeling clothes while go-go dancers shimmied in the store windows amusing the large crowd out on the sidewalk trying to get in.

The whole thing was loud, loud, loud! All of the other designers were proudly showing off and talking about their clothes to anyone who would listen while I skulked around anonymously, feeling out of place. I had practically nothing there to show off. I had nothing to do. I stayed for about a half hour before sneaking out, getting on the subway, and going home, where I had a nice long cry.

The next morning I was up early and at the studio at eight o’clock, just as I had been every other day before the opening. I was ready to put that depressing evening behind me and just keep going.

My clothes were delivered a couple of days later, and I finally was able to see my things in a store setting. I almost cried again, I was so proud of how everything looked, especially the label. However, when I went back to the store a few days later I was concerned: most of my stuff was gone. The racks were practically empty. Hysterically I asked the salesgirls what had happened to my clothes. They looked at me like I was crazy and said, “Well, they were sold, of course.” I didn’t know what to say. I mean, obviously, I was elated. To think girls whom I didn’t even know were running around town in my stuff!

Paul even called me that night to congratulate me on my “sell-through,” which I learned was retailese for “my stuff sold.” The production people also called, asking when they could get more samples. All of a sudden it was like, Okay, time to get serious. We never followed what I now know is a proper design schedule. In the real world you design and produce so many collections per season. There are two seasons per year—fall and spring. At Paraphernalia we designed stuff constantly. If it was summer we produced summer clothes; in winter we produced winter clothes and so on . . .

Twiggy in Betsey!

Anouk Aimée in my long-john nightshirt dress made of silvery jersey

In my messy workroom

I didn’t actually go to Paraphernalia very often, but I remember Paul coming into the store one time I did happen to be there. It was a cold December day, and he went off the rails when he saw that there were no coats in the store. So you guessed it. I rushed back to the studio and designed a bunch of coats. Tulah and I worked on the patterns that night, and the samples were ready in a couple of days. Paul had coats in the store just in time for the first blizzard of the season. This experience taught me another retail term, “wear-now.” The people who shopped at Paraphernalia were definitely not the types who planned ahead. There was a popular saying at the time: you go to Paraphernalia for clothes to wear out on Saturday night and throw out on Sunday morning. We were definitely a wear-now store.

Rock bands, artists, hip downtown kids and their uptown wannabe counterparts came to shop at Paraphernalia or just hang out. It was the only place to get the far-out kinds of clothes they wanted to wear. And it was unisex! Which was a totally unique concept for the time. With the exception of department stores, men and women had previously shopped at completely separate places.

With Michael Mott, Paul Young, and some models wearing our designs

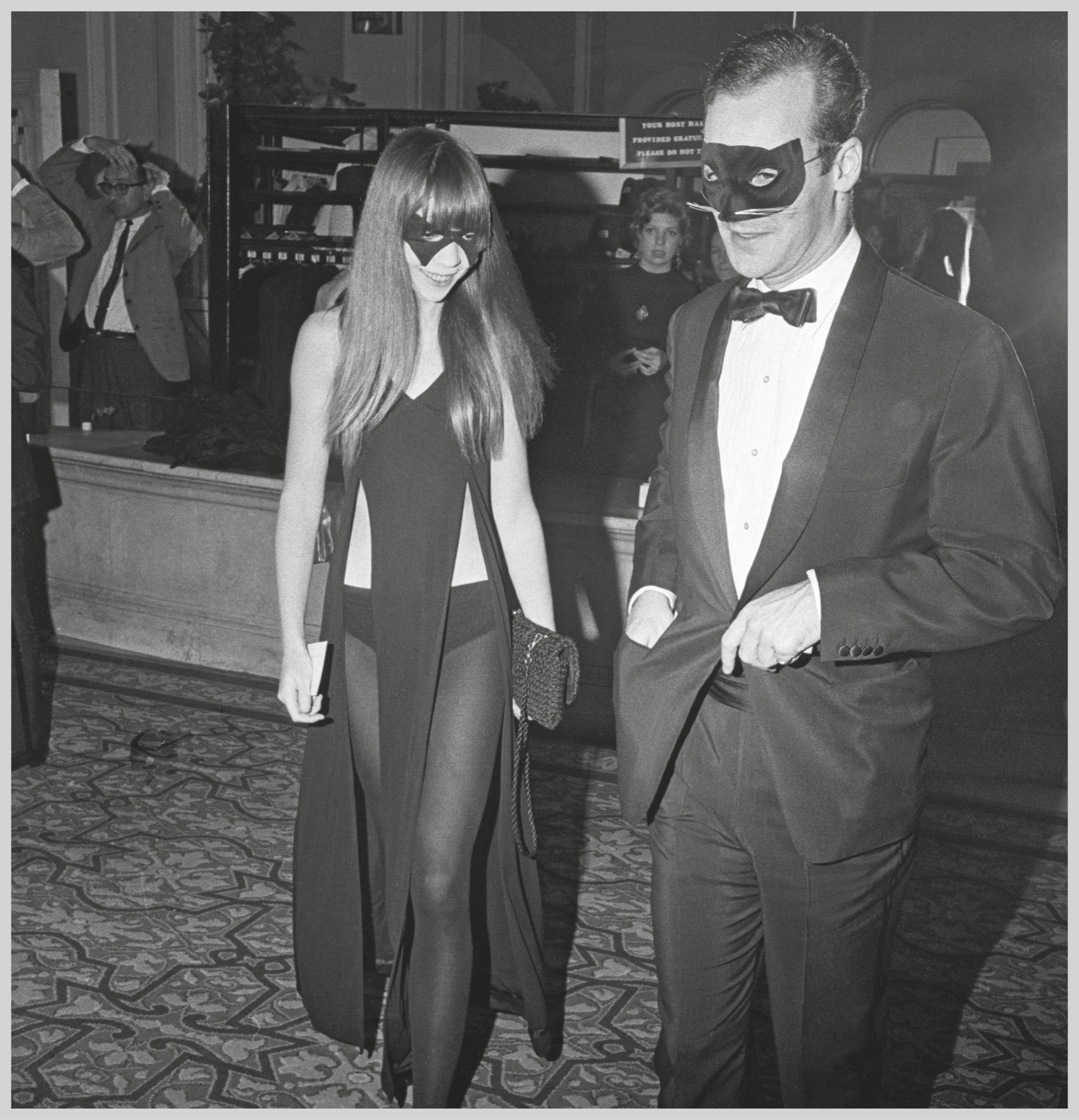

Penelope Tree in the outfit I designed for her to wear to Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball in 1966

Veruschka in my Enkalure nylon bathing suit

This was a dream job for me if ever there was one. And it wasn’t just a one-way street. Paraphernalia was very good for me, but I was also very good for Paraphernalia. I consistently outsold all of the other designers in the store. I may not have made the most money for the company, because right from the get-go I designed with one eye on creativity and the other on affordability. I told Paul that I didn’t want any of my clothing to cost more than ninety-nine dollars, which I equated to the cost of a weekend in Puerto Rico. That was the yardstick I used; very scientific.

And believe me, as hard as I was working I also took many ninety-nine-dollar weekends in Puerto Rico!