By 1977 I had been freelancing for almost four years, and it just wasn’t doing the trick anymore. Even though I did have my name on some of the labels, it didn’t feel like the real thing. I was getting tired of designing what was essentially someone else’s vision.

One afternoon, while having a drink with my good friend, and favorite designer, Giorgio Sant’Angelo at Bill’s Bar in the Garment District I was going on and on about how I felt as if I wasn’t moving forward in my career. I was frustrated because I wanted to do what I wanted to do, and nobody seemed willing to hire me for that. He told me flat out, “Betsey, no one is going to do this for you. You need to do it for yourself. If I were you, I would just design a line, plan a fashion show, and announce you’re back.” Coming from Giorgio, this was a major statement. He was such a gentle man, and I never saw him get his feathers ruffled. But he seemed adamant about this, so he must have meant business. Or he could have just been fed up with my complaining.

My fave, Giorgio Sant’Angelo, who told me to “Just do it!”

For at least a year I had been looking for a company that would hire me and let me design my own line while they footed the bill. I knew such companies existed because, up to a point, that was the way things worked for me when I was at Alley Cat. Puritan, their parent company, owned a bunch of different labels, and each had its own designer. I only left Alley Cat when the label folks got too controlling, because I hated that feeling of being stifled. I had been spoiled at Paraphernalia. There I worked day and night, but I could make anything I wanted, as long as it sold. Lucky for me, it did.

I knew I still could design a line that would sell. But I thought taking on the business side as well would be overwhelming. When Giorgio dared me to stand on my own, I flashed back to six months earlier, when I had gone to see Frank Andrews, my favorite psychic. He said to me, “Betsey, why don’t you just go to the beach and relax? You shouldn’t be trying to start anything new at this point in time. It’s simply not in the stars for you right now. Give yourself some time. Within six months I see you living in a new place and sporting a whole new look.”

As Frank’s words came back to me I realized the six-month waiting period was over. I should have taken his advice and just gone to the beach instead of beating myself up over my work situation. No wonder it hadn’t felt right before. Now, I looked around my loft, which I had just painted hot pink and acid green, and realized that in effect I was living in a new space. I’d also cut off my curly brown hair, dyed it black, and wore it spiky and messy, like Keith Richards. My whole look had changed. So if Frank had been right about my living space and my appearance, maybe he was right about the future of my career as well.

Giorgio’s real kick-in-the-pants advice, along with Frank’s prediction, got me thinking in a whole different way. I had never really had to pursue jobs before. They had all more or less landed in my lap. Now I was finally going to take the lead and roll the dice. The more the idea of starting my own business sank in, the more excited I got. My gears were turning as I considered how to put the pieces together into a master plan.

I knew the first thing I would need was a partner in crime. There was no way I was going to do this alone. I immediately thought of my friend Chantal Bacon.

We’d met a few years earlier when she was the rep for the brief life of my Betsey Johnson Kids line. She did a great job of selling the line, so I knew she had that part down. Currently she was repping Cathy Hardwick’s clothing line. As for the other business stuff, I wasn’t so sure, and I suspected that it might be a challenge for her. I didn’t get too hung up on that, though, because I liked the idea of winging it with a girlfriend whom I trusted, much more than hiring someone with business savvy who was no fun to be around. Also, having worked with me before, I knew she really got me and my designs.

Chantal and I clicked. We had lived kind of parallel lives on some levels. While I had experienced the swinging sixties and the boutique world, Chantal was part of the early seventies glam life, working as a model as well as on the King’s Road in London, at a boutique called Alkasura. It was pretty famous for catering to the likes of David Bowie, Bryan Ferry, Marc Bolan, and anyone who was anyone in that seventies scene. And just like me in the sixties, she had to get out before she burnt out. Which is how she found herself in New York selling my line. So we pretty much had a lot of the same sensibilities.

If I could persuade her to jump in with me, she would be the Butch Cassidy to my Sundance Kid, or a Bonnie to my Clyde. I set up a meeting for the two of us at Café Un Deux Trois, a cheap but cute place on West Forty-Fourth Street close to her apartment. I walked in not knowing whether Chantal was open to my kind of adventure. I knew she wasn’t completely happy working for Cathy Hardwick, but she needed the financial security. I sat her down, had a sip of the house wine, and summoned all the confidence I could muster. “Look,” I said, “I want to make you an offer that I think will be really good for you.” I wasn’t into negotiating, I just went in with my best offer—the two of us in a complete and equal partnership. I didn’t want to think of it in any other terms. Not only did I not want a boss, I didn’t want to be a boss, either.

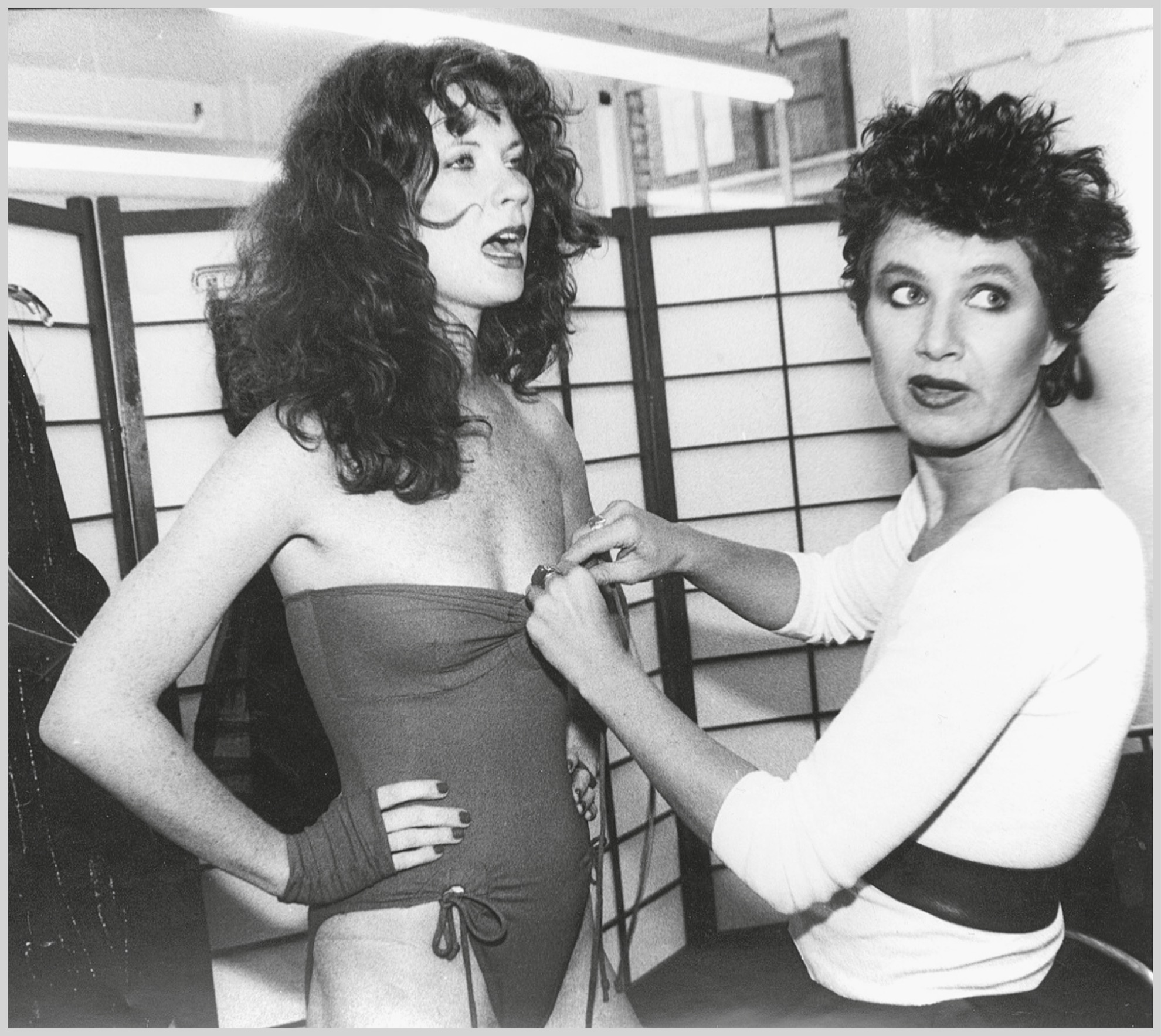

I launched into my plan, touching on my idea for “A Wardrobe in Stretch,” and about this new DuPont fabric I’d found called cotton Lycra. I explained to her that the clothes I wanted to make were the kind of stuff I wanted to wear, and there had to be lots of other girls out there who thought like I did and would want to wear it, too.

Then I took a deep breath and tried to gauge her first reactions. She had an absolute poker face, so I decided to just move ahead as if she were enthusiastic. I brought up my one reservation about teaming up with her—she was partying a lot and had a series of boyfriends who, quite frankly, frightened me. I wasn’t being judgmental. God knows I was playing the field and had my share of bad-news boyfriends, too, but I was trying to put that behavior behind me. I got very serious and told her she would have to settle down and leave all that stuff behind her if she wanted to accept my offer. I needed someone who was committed to the business first, because I was just that serious about starting a company with her.

I finished my spiel, and still she barely said a word. Chantal’s silence seemed never ending, and I found myself practicing my signature on the paper tablecloth. I was already thinking about our logo and wondering at this moment if it was doomed to be seen only by the busboy throwing it out when he cleared our table.

Finally she said, “Can I have two weeks to think about it?” I lifted my hot-pink marker from the tablecloth and stared at her. I was extremely surprised. I had thought she’d jump at the offer, but I agreed to give her the two weeks. I didn’t know anyone else I wanted to go into business with, and I couldn’t imagine failing right out of the gate—let alone disappointing Giorgio and my psychic, Frank. I had to stay positive.

During the time I was waiting for Chantal’s decision I kept myself busy by actually designing the collection. I had been experimenting with cotton Lycra and planned to create a series of basic shapes: leggings, skating skirts, long-sleeved tees, and a few pieces that could work on their own or in conjunction with the whole collection. My key idea was that the entire line would be convertible. Meaning each piece worked perfectly with all the other pieces. It was all mix and matchy. And as I had promised, it would be an entire wardrobe in stretch. Cotton Lycra is a fabric that had been used only in athletic wear. I wanted to elevate this unconventional material into something more, something new, and, I hoped, something that people would want.

I had first discovered the fabric at a factory in New Jersey when I was sourcing something much less interesting for a freelance gig. It was basically stretch cotton shot with Lycra, which gave it a four-way or circular stretch, as opposed to two-way stretch, which was all we had to work with up until then. The closest thing I had previously seen would have been the football jersey material I worked with at Paraphernalia. Using cotton Lycra for real fashion would be at the very least a novelty, not to mention supercheap to produce.

When the two-week waiting period finally ended, I walked nervously to Un Deux Trois to meet Chantal. I had my designs in a portfolio tucked uncomfortably under one arm. I arrived first and, being the superstitious person I am, sat at the same table where I had made her the offer. I had already decided that I wouldn’t order anything until I heard Chantal’s answer. If it was no, I would just leave, devastated, and have to rethink the entire situation. Her turning me down was a very real possibility.

She arrived ten minutes late and sat down. Neither of us said anything. There weren’t even any awkward hellos, and I could tell she was as nervous as I was. When the waiter came to the table, Chantal—without saying a word to me—ordered a bottle of champagne and flashed me an all-telling smile. I exhaled for the first time in fourteen days.

As soon as that cork was popped and we toasted, I pulled out the portfolio that I had been busting to share with her. She immediately understood the designs. She loved the idea of an entire collection based on cotton Lycra and was totally on board with the concept of activewear as fashion. She even said the words any designer would want to hear: “If I saw this in a store, I would buy it.”

Chantal asked for one of my markers, and we both sketched out notes, questions, and drawings that would become the seeds of our business plan. First up, our biggest expense would be a workspace and a showroom. I would also need a pattern maker. I knew how to cut and sew, but pattern making is a very specific skill. I can do it but I’m not great at it, and we needed someone with a real talent to draft for us. We started listing production personnel we’d need to hire right off. And then, of course, we would have to stage a fashion show. Because, as Giorgio had told me, once I made that decision, it would have to be full speed ahead. No backing down. I’d need to rent a venue months in advance and hire models.

The list of expenses was starting to add up pretty quickly. I figured if we could somehow come up with two hundred thousand dollars we could pull it off. And I’m not just talking about the show, but actually starting the company.

As I finished the champagne, my first naïve idea was that we would go to a bank with our plan and simply apply for a loan. Isn’t that the way you start a business? So a few days later Chantal and I dressed in what we thought were very conservative outfits. That was my second naïve business idea. Conservative for us meant anything that didn’t have sequins or satin on it. We dressed head to toe in black—me with my punky chopped-up Keith Richards hair, and Chantal with her wild flaming red mane.

I set up a meeting with a banker from the Benjamin Franklin Bank, whom I had worked with when I was with Alley Cat. He always told me how impressed he was with how I handled the finances for the label. I decided to cash in on the relationship. This is how we ended up at Penn Station boarding a train for North Philly

When we arrived at the bank, good old Ben Franklin was there to meet us. Looking every inch the banker in his three-piece suit and wire-rimmed glasses, he escorted us to his desk, which was right out in the open in a massive old bank building with vaulted ceilings and marble floors. The sheer size of the place made me feel even smaller than my actual five-foot-four frame. We sat down and he asked, “Now, what can I do for you?” I repeated what I had discussed briefly with him over the phone. I told him that we wanted to start our own clothing company. I laid out our plan as best I could and told him how much money I thought we would need.

He seemed amused that we knew so little about how these things worked. He patiently explained that if we needed two hundred thousand dollars we would have to come up with half the amount and get someone to co-sign for a bank loan for the other half. Our big meeting was over in five minutes. With the wind knocked out of our sails we hightailed it back to New York and went to the café to regroup.

As soon as we sat down, out came my markers, ready for another assault on the tablecloth. I had thirty thousand dollars saved, but that left seventy thousand to go before we could get our loan. We made lists of anyone and everyone who we thought could or would lend us money. And believe me, it wasn’t a very long list. We started with our parents.

My dad had always been very supportive of me and my career. He knew I worked extremely hard and was very serious about this venture. And I had a good track record. Dad was the one who had lent me five hundred dollars to start my T-shirt business back in the Mademoiselle days, which I paid back pretty quickly. This time it would have to be a lot more than that.

Chantal was fairly confident that her mother could front her some money as well. Not that her mother was a rich lady—she wasn’t. But like my parents, she was always right there to back Chantal’s choices. This was the same woman who’d championed her daughter’s decision to give up college after six months to backpack around Europe.

So on the same day, Chantal set off for south Jersey and I headed to Terryville to lock down loans from her mom and my dad. Even with parental cooperation and my savings, we would still be short. It looked like I was going to have to say yes to Bayer aspirin. Let me explain.

A few weeks earlier I had been contacted by a representative from Bayer asking me to appear in a magazine ad. Their campaign was going to feature people from different high-stress industries. I think there was going to be a surgeon, a pro golfer, a cop, a fireman . . . and me. (How a fashion designer’s stress level compares to that of a surgeon or a fireman is beyond me.) Right from the get-go I told them I wasn’t interested. To me it seemed painfully uncool and, in a way, as if I was selling out. I mean, I was always the outsider, the hip downtown designer. Bayer aspirin wasn’t exactly the trendiest product around.

But now the money they were offering seemed too good to turn down. I vaguely remembered my mother taking Bayer aspirin when I was a kid and realized I must have taken one or two of them in my life. Who hasn’t had a headache? I called the Bayer rep back and said I would do it.

With that job I made ten thousand dollars for the company start-up, and my moral compass and street cred remained more or less intact. I can still picture the ad. Across the top of the page it said “Betsey Johnson, NYC Fashion Designer.” Beneath the type was a photo of me in one of the striped Lycra outfits from the collection that I planned on producing. I had sewn up a few of the pieces just for the shoot, figuring it would be a good marketing ploy. I was photographed sitting at a drafting table in a reasonable facsimile of a design studio with pattern pieces hanging from the ceiling and bolts of fabric draped over tables. I was rubbing my temples, and the copy read “I’m in the fashion biz and I am only as successful as my last collection. With that kind of pressure, I need a pain reliever I can count on” or something silly like that. They had asked me to feign a pressure headache, and believe me, with all I was going through, I wasn’t acting.

Chantal’s mother agreed to lend her thirty thousand dollars. My father was going to come in as an equal partner with Chantal and me for thirty thousand. With my thirty thousand dollars in savings and the ten thousand from Bayer, we had the hundred thousand dollars the bank required to loan us the balance . . . with my father co-signing. Whew—we did it!

We found a small space on West Thirty-Fifth Street in the Mary McFadden building that could be split into a workroom and showroom. Chantal, who had the perfect body, would double as my fit model and our one-person sales staff. We bought cheap red paper folding screens from Chinatown to separate the spaces. The walls were all painted white, and the floor was high-gloss red. In fact, one of Chantal’s responsibilities was to paint out the floors every Friday night. She would start in one corner and work her way toward the door, the whole time wearing stiletto heels! We kept that place clean and as neat as a pin.

The beginning—me and Chantal in our first workroom/showroom

We were both working like dogs. Chantal was still repping for Cathy Hardwick during the day, at least when we were first getting started, and I spent my days designing the clothes. We paid ourselves the tiniest salaries we could afford to live on, so we subsisted on one can of tuna fish each per day and the cheapest bottle of wine at Un Deux Trois to close out the long work shift. We made the café our workspace away from work and stayed there late into the night, always at the same table, which was covered in white paper. All the tables had white paper and a glass of colored crayons. So it was an easy, breezy workroom. We talked to each other nonstop about our progress toward launching the show. I’m sure the restaurant staff thought we were a couple, because we were absolutely inseparable.

My dad, meanwhile, was feeling a little left out. He didn’t understand the industry, or our ways of working—which were haphazard at best. He wanted to be involved in everything we were doing, and it just wasn’t realistic. He couldn’t sit with me and Chantal for hours on end discussing strategy or whatever it is we were trying to work out. Nor was he comfortable with Chantal being an equal partner. He and I had quite a few arguments about that. Then he wanted a traditionally laid-out business plan, and I used to say to him, “Daddy, the only plan I have is for all of us not to go broke.” It wasn’t long before I asked him if he would be interested in being more of a silent partner. We eventually agreed that over time Chantal and I would buy him out. I love my dad, but it just felt right for Chantal and me to be running things solo, because we were so in sync.

The next big decision that we had to make in sync was where to stage our first show. I really liked St. Clement’s Church on Forty-Sixth Street between Ninth and Tenth avenues. A section of the building was an art and performance space—I think you could refer to it as off-off-Broadway—that was the perfect size for me. It held only about 150 people, so it wouldn’t feel cavernous and empty if no one showed up, which was one of my biggest fears. And it had a proper proscenium stage, which I liked so much better than the typical runway. They rented the space out for charity events. We got if for five hundred dollars.

When I brought Chantal with me to see the church, there was a show featuring the artist Red Grooms, whom I loved, but we quickly realized that the space was booked up months in advance. They did have one date available for rent—August 10, my birthday. Again the stars were aligning and I saw it as a sign that we were on the right track. Chantal also saw the potential for a great launch there, and together we enthusiastically said yes right on the spot.

St. Clement’s was located in a very sketchy area really close to the entry to the Lincoln Tunnel, a neighborhood notorious for prostitution. Girls would solicit guys in cars right by the tunnel entrance, and the guys would take them through to a no-tell motel on the Jersey side. I always wondered how the girls got back.

After we left the church we walked over to a corner, looking for a cab. Chantal was wearing a long, tight pencil skirt, leather jacket, fishnet stockings, and high heels. I was in a very similar outfit. Soon a cop came up to us and said, “All right, girls, move along.”

Chantal looked at me and said, “He thinks we’re hookers!” She was shocked. But I was kind of flattered. I thought those girls looked great!

My concept for the show was, not surprisingly, a bit unusual. Since there was no proper runway, I decided we would stage it like my dance school recitals had been presented, with all the girls appearing at the same time. The theater had a small orchestra pit, where I would lay out the entire line flat on the floor. When the curtain came up, the girls would be standing in a row, wearing either bathing suits or body suits. They would step down off the stage into the pit, dress themselves, and then change outfits right in front of the audience.

With this choreography, if that’s what you could call it, I was making the statement that cotton Lycra could work for all types of garments: a wrap dress, a dolman-sleeved jacket, a crop top, a bikini, a tight body-conscious dress, and a fit and flare—everything. The collection was completely unlike anything that was being offered in the mainstream at that time. I was giving people something they didn’t know they wanted—basically it was activewear as streetwear as fashion, which was unheard of back then. It’s everywhere now.

Prepping for my first fashion show

Even though the girls would be practically naked in front of a crowd, there was no question of modesty, because most of the models I hired were strippers, and a few were even girls from the Lincoln Tunnel entrance. I knew the strippers from the Garment District where they worked during the day as fit models. I met the hookers when we came to check out the church and theater. They were all pretty and had great bodies, which is why I didn’t mind the cop’s comment earlier. Plus, they really rocked their skimpy outfits out there as they worked by the tunnel.

And the curtain goes up. They’ve got legs!

I had done fashion shows before at Paraphernalia and twice a year with Alley Cat.

But it’s a whole different ball game when you’re spending your own money. You have to get very creative. Hiring strippers and hookers and actresses and salesgirls from hip stores was an aesthetic choice but also an economic one—we definitely couldn’t afford real models hired from an agency.

There was a lot to do, and Chantal and I did so much of it by ourselves. Right up to the last minute I was cutting and sewing. Only a couple of nights before the show, I was still way behind schedule, and out of desperation I had to enlist Chantal to help me cut garments. I had been up for two days straight and was starting to get loopy. Chantal has many, many talents, but cutting out garments is not one of them. She made such a mess of some simple circle skirts that it looked as if a shark had been at them. I ended up cutting them into shorter skirts rather than waste precious fabric. When I got upset about having to do the extra work and about the potential waste, she burst into tears. It’s very out of character for me to lose my patience, but that’s just how frazzled we were.

We had moments where we really doubted that we could pull it off, and if we did, what then? What if nobody liked the clothes? What if nobody bought them? We tried not to get too hung up on the what ifs and just went full speed ahead, fueled by tuna fish and not much else.

When August 10 finally arrived, I was a nervous wreck. I hadn’t slept; the clothes were barely finished; I wasn’t sure if the stage setup would work. I wasn’t sure about anything. No one was cooperating. The models were all over the place. The lighting guys were nowhere to be found. The DJ was late. Finally, I went down to the stage and just crumpled to the floor, sobbing beyond control. Suddenly everyone stopped what he or she was doing and snapped into shape. In no time the stage was lit, the models were partially dressed, and people started to stream into the room. At least my worst fear hadn’t come true—we would play to a full house.

I’d sent out invitations to absolutely everyone I had ever met. I still had some contacts from Paraphernalia and Alley Cat and was grateful that they’d agreed to share their lists with me. Edie Locke from Mademoiselle did the same. Every seat was filled, and there were even people lining the back of the theater. The great turnout may have been partly due to our starting off with a show for the holiday season—there weren’t many competing shows. Another brilliant suggestion from Mr. Sant’Angelo.

As soon as I got all the girls positioned and had all the clothing in place, I cued the lighting guy and the DJ, who were both friends of mine. I called in a lot of favors to put on this show and now I could stand back and see if they paid off. I’d like to say that the show went off without a hitch, but a lot of the time the girls looked as if they didn’t know which end was up. There was a lot of fumbling, dropping of clothes, and more than a few “wardrobe malfunctions.” But the girls were all having so much fun that none of the mistakes read as such, and they only added to the general kooky atmosphere that I was looking for.

The audience really got caught up in the spirit of the show, considering how out there it was and by the finale they were on their feet cheering and applauding. Chantal and I were over the moon, and we both took a bow together.

Directly after the show it was back to the workroom. I hadn’t made any arrangements to have the clothes sent back, so we packed the rolling racks ourselves as best we could, and the models wheeled them back. This was the start of another superstitious tradition, one I continued for years.

Once back at the showroom Chantal and I toasted each other, and I told her right there, midsip, that I was leaving the next morning for two weeks in Mexico. She choked on her champagne and just looked at me and started laughing and said, “Oh, very funny! You’re joking, right?” “No,” I told her, “I’m serious. I’m done. It’s your turn. Now we gotta sell this shit.” She looked like a deer caught in the headlights. I told her she had nothing to worry about. The show had gone great, the crowd seemed to love it, and there were plenty of buyers there. We even got on the cover of Women’s Wear Daily. I told Chantal I would see her in two weeks. I had no intention of checking up on her. Equal partners, remember? She could go away on her own trip as soon as the selling was done. Which, confidentially, it never is.

When I returned to New York, I was sunburnt, rested, and eager to get started on my next collection. I couldn’t wait to get to the showroom to see how the line had performed. When I arrived at nine a.m., Chantal had already opened, and the place looked as if it had seen some action. She was relieved to see me, but the news wasn’t great. Buyers had come to look at the collection, but there were practically zero sales. Pat Field had bought a handful of styles for her store on Eighth Street, but that was it. We now faced new worst fears coming true. The stuff was a little too far out.

The lack of interest in the line surprised me because the show had been so well received. All the papers were saying stuff like “Betsey is back!” But when that initial wave of praise passed, it seemed as if no one actually wanted to wear the clothes, which in my heart of hearts I truly didn’t believe could be true.

I was furious about the lack of sales. I knew the designs were good and I knew in my gut that the time was right. Maybe we just didn’t know how or where to look for the right buyers. I don’t know how much more I thought she could have done. I wanted Chantal to call all of her old clients from her time at Cathy Hardwick. But they were hardly the same customers for my clothes.

That night we went back to Un Deux Trois, and I planned to have it out with Chantal. I wanted to discuss the sales situation and was ready to blame her, but she was having none of it. She would apologize, and that was it. She wouldn’t give me the fight I wanted, and I mistook that for a lack of interest. It was the first time we had ever had a major disagreement. To this day I feel awful for lashing out at her. I was just as much to blame, or should I say, neither of us was to blame. We simply were ahead of our time and hadn’t found “our girl” yet.

A few days later, as luck would have it, the good people from Fiorucci paid us a visit, right out of the blue. Their buyers had been at the show and only now had a chance to come see the line. Fiorucci was a boutique on Fifty-Ninth Street, right around the corner from Bloomingdale’s, but it was miles away in terms of concept. It wasn’t a big department store but a huge, crazy boutique, disco-sexy in a very Italian, European way—making it the most happening place at the time. It was owned by the great Elio Fiorucci, who created what he called the “New Happy Sexy Girl.”

Fiorucci was the one store that could really get us off the ground, and its blessing could mean everything. It was also validation that I was on to something, that I was doing something right. They placed such a large order that they even suggested giving us our own section in the store and launching it with a party and live models in the windows. Of course, this was right up my alley as we had done the same thing lots of times at Paraphernalia.

Coming down off such a high wasn’t easy, but I had to start in on the second collection right away so that it would be ready in time for the next six-month fashion cycle. I realized very early on in my career that the whole fashion business is like a roller coaster that you really love: as soon as one ride is over, you get back on for another.

With the second collection I knew I wanted to remain true to what had worked the first time around, but I also wanted to expand on the idea. So I designed a line that retained most of the basic shapes and fabrication and added a few more. The big change was the color—I wanted to try a very different palette. Where before it was punk-rock black and white or red and white or all black, this collection would be turquoise and black and hot pink and black. And after seeing the B-52’s at CBGBs, with Kate Pierson and Cindy Wilson wearing Day-Glo bathing suits onstage, I was like, Yup, that’s what I’m gonna do. That would be my twist for this collection.

Out and about with Chantal after my Spring ’80 fashion show

With my old friend Robert Mapplethorpe in 1985 just a few years before he passed away from AIDS. Such a tragedy. He was brilliant!

Neither Chantal nor I knew anything about projecting how many of each garment to cut.

I had never had to worry about that aspect of design before. At Paraphernalia we were only cutting in small numbers—as many as could be sold in one week at our one store. At Alley Cat I had nothing to do with production. The garments were mass-produced, and an entire department was responsible for that end of it. Now that we were on our own, determining production numbers was a real wake-up call, and one that we should’ve anticipated.

Chantal came up with a formula based on no particular kind of reality. She figured that if we had even two customers in every state, then we needed to cut a hundred pieces of each style. See? Like I said, based on nothing. But she figured we had to base our logic on something, so we weren’t just pulling numbers out of thin air. I understood and agreed with that thinking.

Well, we blew it. The collection was a complete failure. We had a couple of small stores in New York City buy a few pieces, but not enough to make even a small dent in our inventory. For the most part, nobody wanted this pink and turquoise collection. Even with our huge success with the first collection, Fiorucci didn’t come knocking this time. I guess people weren’t ready for Day-Glo, which, granted, is pretty much impossible to wear. Chantal could not sell it to save her life—our lives!

This time I knew better than to blame Chantal. We discussed it like adults and decided that she and I would fly to Europe and literally go door to door, from boutique to boutique, and try to offload the collection. Based on our success at Fiorrucci, we knew we were big with the Italians, so that’s where we went. We eventually sold a lot of our inventory at heavily discounted prices. I wanted both of us to go into the shops and chat up the clothes, but Chantal knew better. She was a Taurus and therefore much more practical than me. She made me wait down the street while she struck the deals. I would have practically given the clothes away.

This second collection taught us both a very valuable lesson, one that I’ve carried with me for the rest of my career: you are only as good as your last sale. Nobody buys something because they liked what you did a couple of seasons ago; that would be insane. You have to move on, and you have to keep going with something different and salable.

I may have been feeling way too many growing pains and running low on cash, but I have always been in my own way a businesswoman. Or, should I say, in one way or another, I have always been in business—as far back as I can remember. Literally as far back.

Remember when I was four years old I charged for dance classes and recitals in the backyard. When I was fourteen, I ran my own dancing school. I designed and sold T-shirts and dresses at Mademoiselle. I opened Betsey Bunky Nini. I wasn’t gonna let a little thing like one far-out collection get me down. I was going to keep going.

As I said, we sold a lot of the overstock, but not all of it. We still had bags of stuff and no clue what to do with it. Enter that lucky star I keep mentioning. I happened to run into Annie Flanders on the street one day. Annie was an old friend and the style editor of a small downtown magazine called the SoHo Weekly News and a big supporter of my work since the very beginning. I filled her in on what was going on with me and my predicament. She thought the only logical decision would be to open a shop. She said that she was constantly running into girls who loved my stuff and wanted to know where they could buy it, and it just made sense to have my own store. Also, she added, I wouldn’t be at the mercy of someone else’s (i.e., boutique owners’) whims. I could call all the shots. Of course, this last bit appealed to me. It was a good idea, but opening a store sounded like such a huge undertaking. We certainly didn’t have the bucks to do anything remotely like that. I decided to let the notion sink in for a while.

A few days after we ran into each other, Annie called me very excited and told me she knew of the perfect location. A used clothing shop had just closed on Thompson Street in Soho. She knew Soho like the back of her hand, and it just so happened she was friendly with the owner of the building and knew he was worried about finding another tenant, as the space was really small and awkward. This was 1979, before the western edge of Soho was happening. It was still very sketchy, and you could easily get mugged in broad daylight. But I didn’t let that bother me.

By this point I had filled Chantal in on the idea, and she was on board. A few days later we went to check out the space. Annie wasn’t kidding. It was more like a phone booth than a proper store. Still, we made a deal with the owner on the spot and signed a month-to-month lease. We were told we could move in right away. I think we may have been the first-ever pop-up shop.

Once the lease was signed I got right to work decorating the place. I used the hundreds of fashion sketches I had saved from Paraphernalia and Alley Cat to paper the walls. We bought some cheap chrome rolling racks, and I hired some of the girls who had modeled for me to work as salesgirls. They graciously agreed to get paid on commission, and some of them even bartered their time for clothing. Thank God, because our small arsenal of cash was dwindling fast.

Given the dangerous neighborhood we were in, I worried about the girls’ safety as most of them were strippers and definitely looked the part. I didn’t have to worry for long. The store was located right next door to an Italian social club, and the guys who hung out on folding chairs in front kept an eye on them. Not in a creepy way. But in a loving, sweet, and protective way. Nobody walks by an Italian social club and harasses anyone!

Annie’s prediction was right on the money. People flocked to the store, and I had to work day and night to keep it stocked. Annie was so enthusiastic that she wrote a story about the shop for her paper, even featuring us on the cover with the headline “I’ve Seen the Future and Its Name Is Betsey Johnson!” Lucky for us, the New York Times was on strike that week, so the SoHo Weekly News got much more prominent placement on newsstands all over the city. Business went through our tiny roof.

It was actually a riot to watch traffic in and out of the store from across the street. If we had more than two customers at a time, the salesgirl working that day, decked out head to toe in striped Lycra of course, had to step out onto the sidewalk. Those girls spent a lot of time outside. And before long they were joined by more customers, waiting their turn to go inside and shop.

Spring 1979 model with my dear, dear friend Bill Cunningham

First collection with girlfriends and Chantal (far right)!

After about six months it was crystal clear that we had outgrown the little space and kept our eyes open for a new one. Word of mouth had brought girls to our seedy little block in Soho, so we didn’t want to stray too far. And we didn’t. Without doing any research at all I found what we were looking for right up the street. This time a pet shop had recently gone out of business, and I immediately jumped on the chance and called the real estate agent listed on a poster in the window.

Now we were going to have to sign a real lease and plunk down first and last month’s rent as well as a one-month security deposit. Our tiny shop had made money, but we always had to put that cash back into the business to keep the store stocked. We pocketed as little as we could afford, just enough to pay our own rents and to keep eating. It was all about the store.

With this new move, Chantal and I would once again be living on tuna fish. With us it was always one step forward two steps back. But we were fighters who really believed in what we were doing. We were the little engines that could.

Now it was time to put my thinking cap on again and figure out how to decorate this much larger space. I really didn’t have many options, and I thought to myself, Okay, Betsey, what is the cheapest way to decorate? And then it came to me: color. The cheapest and easiest way to decorate is with paint. And the most effective way would be to do it in the most hit-you-over-the-head way possible. I thought about the loft I was living in at the time, the one I had recently painted hot pink. Hey! That would work for the store as well. I painted the walls and ceiling the same shade and bought more black-and-white peel-and-stick tiles for the floor. That’s how the formula I would wind up using in my stores for many years came about. It may have been born of desperation, but it looked great!

For my last little bit of decorating I hung up an original portrait that Andy Warhol had done of me years earlier in the back room of Max’s Kansas City. (Oddly enough that was one of the handful of times I had actually met Andy. As I said much earlier, I was not a fan of going to the Factory.) It was a crude drawing done on a cocktail napkin but it was signed. I’d had it framed way back when and never knew quite what to do with it. The wall behind the cash register seemed like the perfect spot to show it off. It hung there for about three days before someone stole it. Shit!

How to Meet, Marry, and Divorce in Three Months: Husband Number Two

Not long after opening the Thompson Street store, I found I was spending a lot more time in Soho than ever before. Being a creature of habit, I started getting my morning coffee every day at a café down the street from the store called the Cupping Room. Always the same, black with two Sweet’N Lows, paper cup to go.

There was a really cute guy named Jeff who worked behind the counter as a burger flipper. He had long, curly, flopsy-mopsy hair and huge brown eyes. I got chatty with him and flirted on a daily basis. Eventually, I started getting my coffee to stay. After about a week or so we were dating.

I may have been focused on my new business and my first store, but I could always find time for romance. And why not? The balance between business and pleasure has always been super important to me.

The relationship with Jeff was no big deal. In fact, it was the most lightweight, superficial thing you can imagine. Dating him was like having a vacation boyfriend—adorable to look at but nothing at all to talk about. I didn’t even care that we weren’t having great sex, because he was just so great to look at, and that was enough.

That said, and before I knew what was happening, he moved in with me at my loft on Church Street. You know how it goes, they start staying over more and more and going home less and less, until you realize they haven’t gone home for weeks, and then they tell you they gave up the lease on their apartment.

Lulu was five years old at the time and true to form she absolutely hated him. She could always spot a phony a mile away even at that age. I, unfortunately, was not born with that gene. She saw something in him that I was too lovestruck (or blind) to notice.

One late night not long after Jeff formally moved in, he came home absolutely drunk out of his mind, stumbled into my Japanese folding screen, and sent it crashing to the floor. Shouting and muttering, he started throwing anything breakable. Half asleep, I wondered whether it was my porcelain dolls or my vintage art glass that he was hurling across the loft. Not that it mattered. Lulu had been sleeping next to me and just then woke up terrified.

I didn’t waste a minute. I grabbed Lulu, and we raced out the door in our nightgowns, got into a cab, and hightailed it up to Chantal’s apartment, where I knew there was a place on her couch for us. She always welcomed me when I needed a safe haven.

The next morning Jeff called, apologizing profusely. He was crying and saying it would never happen again and, like a fool, I believed him. I forgave him. But Lulu never did.

And it’s probably no surprise to anyone that this wasn’t the only time he got drunk and went berserk in my home. But I was a sucker for his making it all up to me the following day. After one such episode—no better or worse than any other—he asked me to marry him. I have no idea why I said yes, but I did.

I certainly had marriage on the brain, because that’s what I was designing at the time—a collection for an entire wedding party: the bride, the bridesmaids, the hot ex-girlfriend, and, of course, the flower girls. In my head, getting married now made perfect sense, and Jeff just happened to be in the picture with me. Maybe at some level I thought getting married would be good for business. What an idea—showcasing my latest collection at my own wedding.

When I married John Cale, it was at City Hall. This time I wanted the big church wedding I’d always dreamt of as a little girl. I chose the beautiful Unitarian Church of All Souls uptown on Lexington Avenue for the ceremony. The interior is all pristine white, just gorgeous, very traditional, and just made for a wedding.

After the wedding of what would end up being a (thankfully) very short marriage

It all should have been perfect. My father walked me down the aisle. Chantal and Sally were my maids of honor, the girls from my store were my bridesmaids, and Lulu was my flower girl. Each of them was wearing a different dress from my “bridal” collection. Lulu’s was an exact copy of mine, which was made of shiny white spandex with a full sweeping skirt, layers of crinolines underneath, and the most ridiculously huge puffed sleeves you could imagine. Right before the ceremony I sewed inflated balloons into those giant sleeves. When the minister pronounced us man and wife, I whipped out a giant hat pin and popped them! Don’t think the irony is lost on me at what a prophetic sign that balloon popping was! A real omen of things to come . . . very soon.

After the ceremony it was off to downtown for the reception at a great big loft/event space called Schmidt’s on Broome Street in Soho. The room wasn’t fancy at all, so we had decorated it the day before with hundreds of white balloons and miles of white tulle draped from floor to ceiling. It certainly looked festive, even if the mood was exactly the opposite.

Lulu was miserable all day. I have a picture of the two of us at the reception in which she’s crying and I’m consoling her. Aside from her not wanting me to marry Jeff, someone had given her a beautiful bride doll, and one of the out-of-control guests had ripped it out of her hands and tore the legs off it. My heart just melted as poor Lulu couldn’t make sense of why someone would do that. Thank God my family was there. In the middle of all the downtown craziness they were a big comfort for her, a bit of normalcy in the midst of my wacky world.

During the reception Jeff spent no time with his new bride. I felt as if he was even going out of his way to avoid me. A few people, including Chantal, pulled me aside to say that they thought he might be high. I told them that of course he wasn’t high—he was just nervous. Which is ridiculous, because no newly married man nods off at his own wedding because of nerves. Once again, I had my blinders on. I didn’t want to know what was really going on. Besides, I wouldn’t have known how to process something so unthinkable, even though I’d been through it before.

Also, I was too caught up in the actual party, which was more like a media event than a wedding reception. I had hired a DJ from the Mudd Club, and it was loud, probably too loud. It seemed as if all of downtown had shown up. Not that they were invited. Word got out and people just crashed.

For a celebration, the general atmosphere was strangely uncomfortable. You had my Connecticut family members trying to mingle with the downtown crazies, and it just didn’t work. Even worse, not one of the guests seemed to believe in the marriage. They just assumed it was some sort of joke. To top it off, I hadn’t ordered nearly enough food, and everybody was starving. I was at the center of it all, of trying to make it work, and it was exhausting. But somehow I got through the last farewell, and at eight o’clock Jeff and I left for our honeymoon.

We were catching a plane to Puerto Rico, but by the time we reached JFK, Jeff didn’t look so well. After takeoff he went completely quiet. Something wasn’t right. He was sweating and irritable. I thought he was coming down with the flu and actually felt bad for him. I couldn’t wait for the four-hour flight to be over so I could get him to a doctor.

When we finally landed and he tried to walk off the plane, he crumpled, and it seemed that something was seriously wrong with his back. With the help of a couple of stewardesses I managed to get him into a cab, but he insisted on going to our hotel instead of a hospital. He kept saying that he would be all right if I could just find him some pain pills.

I spent the next couple of days crisscrossing the island with him looking for a doctor who would write him a prescription. I had to do all the driving as Jeff was in no condition to do so, and I hated driving. I’m a country driver at best, and even that kind of driving I’m not thrilled with. At this point he was shivering, sweating, and getting nastier by the minute while I tried to keep upbeat and accommodating. But after the second day I had had enough.

I came to my senses and put two and two together. The warnings from everyone at the wedding, the flu symptoms, and now this back nonsense: He was going through withdrawal, not back spasms.

We did finally manage to get him pain pills through a recommendation from the concierge at our hotel. I put Jeff to bed and went into the other room to call my friend Tony, who lived in my building back home. Lulu had been staying with my parents, and I asked Tony to get her and bring her down to Puerto Rico to stay with me. He was a dear friend and agreed to do it. My revelation of Jeff’s drug addiction came as no surprise to him.

I made a plan to send Jeff packing as soon as he could pick himself out of bed. The next day he woke up and asked for orange juice, and I told him we were through. I didn’t even bother mentioning the drugs. He was so fucked up on pills that he didn’t seem to hear me or maybe he just didn’t care. But he did leave without causing a scene.

Lulu arrived the next day with Tony. She was thrilled that Jeff was out of the picture and that it was just going to be the two of us again. Tony stayed for a couple of days to make the trip worthwhile, and I was glad for pleasant company again.

When Lulu and I returned home, Jeff and his things were gone from the loft, thank God, but so were a lot of my things. I noticed that quite a bit of the jewelry I had brought back from India over the years was missing. I was furious but mostly at myself. Jeff was a junkie without any real money of his own, just a burger-flipping salary and tips. Where else would he be getting money for drugs?

The first thing I did was change the locks, and the second thing I did in my paranoiac state was to gather up my remaining good jewelry in a giant pile on my bed. I broke every piece apart to remove the stones. I stashed them in a sturdy purse and grabbed a taxi to my Soho store. There, I took the gems and one by one glued them to these crazy embellished frames that decorated the space. I thought that by hiding them in plain sight they would be safe. They were safe, all right, so safe, in fact, that I forgot all about them until years later when someone at my showroom was cleaning the frames and the jewels started to pop off!

I knew I needed to divorce Jeff, but I had no idea where to find him so he could be served with papers. I asked all of our mutual friends, but no one had seen him. It was as if he had disappeared. That is until I heard from his lawyer. Jeff was suing me for damages. We had been married for all of one week, and he somehow thought that he had the right to half my money. He even claimed he had some absurd right to my vintage 1950s living room furniture.

At first I was outraged but calmed down when I realized this was just the desperate act of a drug addict. I knew his lawsuit couldn’t go very far, and it didn’t. I got a lawyer of my own, and the letters from his lawyer stopped pretty quickly.

After our divorce was finalized, I never heard from Jeff again, at least not directly. I was in touch with his sister, whom I had actually become close to. She called to tell me that not long after I dumped him, he had gotten himself clean. He was married and had a couple of kids and was living in Florida, working for his father. I was glad to know that and I was sincerely happy for him.

A few years later I heard back from his sister. She called to tell me that Jeff had picked up the needle again and had died of an overdose. You hear that story too often, and I was especially sorry to hear it now.

You’d think I would’ve learned a thing or two from the behavior of all the druggies I was around in the sixties, never mind having been married to a junkie once before.

So met, married, and divorced, all within a three-month span. It may sound pathetic to some, but the way I see it is, I made a mistake but I corrected it quickly.

I’d be lying if I said I really loved Jeff. I barely knew him and what I did know about him—apart from his looks—I didn’t even like. But I fell so easily and readily that it seemed I was always “in love” with someone or other. When I was really into a guy, I would always do anything for him. This time I just took it too far.

It’s strange because in all other areas of my life it’s always my way or the highway. But where men are concerned? I will admit to having a blind spot.

Expanding

The new store proved to be just as popular as the first one. And I think the customers appreciated that there was now enough space that they could actually try on the clothes, and I know the salesgirls appreciated not having to spend time on the sidewalk. It wasn’t long before we had enough money to open a second store—this time way up on the Upper West Side, on Columbus Avenue.

I never gave a thought to having a store outside New York City, where I felt I could keep my eye on things. But after opening Columbus Avenue, we started hearing some buzz about Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. As luck would have it, the girl who was running the Columbus store was interested in moving out west, and a plan just seemed to fall into place.

At my 60th Street store

We found a real estate agent in LA, and before long she found us a great location that we could afford. I let my West Coast–bound Betsey girl go out ahead and set up the store. The plan was for me to then go out a few days before the opening and paint murals of my fashion sketches as I wasn’t comfortable with anyone else’s decorating the space. The sketches looked like very stylized pinups wearing my clothes and saying sassy things through speech bubbles. The decor was sort of a grown-up version of what was in my tiny little shop. I didn’t finish my work until late in the night the day before the opening, and we had to leave the doors open all day because the place reeked of paint. In spite of the smell people turned out in droves, and the opening was a success. The next day I jumped on the first flight right back to New York.

After the Melrose opening it took us a whole year before we were able to open another store—this time on Newbury Street in Boston, which was the only place to be in that town. The store was located downstairs in an old brownstone. It was supersmall, but we figured it was better to have a small shop in the right location than a bigger one in the middle of nowhere. I will say this, whatever city we opened in, we always managed to be right in the thick of things.

After Boston it was down to Florida, and then back out to the West Coast. In the following few years, before we knew what hit us, we were sitting on a mini empire of ten stores, and a few years later the count was up to twenty. Neither Chantal nor I ever had the notion of conquering the world one store at a time. It just seemed to happen organically. And our system worked for us. As soon as we had enough money in the bank we’d open a store. That was all the business model we needed. I began to feel like the Mildred Pierce of retail. There is a line in the movie where Mildred says, “Everywhere you went I had a restaurant.” In my case, everywhere I went I had a store.

We never had a blanket visual policy in the company as far as the windows were concerned. For each new store opening I’d still go in a few days beforehand, decorate and paint myself silly until I was about to drop, host the opening party, and fly right back home, usually on the red-eye. Through the stores I amassed an army of what I always referred to as “Betsey girls”: a group of like-minded gals who got me and were enthusiastic about the clothes. Apart from that, the girls’ only mandate was which clothes to feature in the windows. As far as propping, they always knew what felt right. They were also our own little in-house focus groups, giving us constant customer feedback. We could find out in an instant what was selling and what wasn’t, what people were asking for—that type of thing. My pink ladies really helped me keep my fingers on the pulse of what was going on in the real world. In that regard I think we were unique. But what did I know? We still worked so far out of the real world of fashion that I had no idea how other companies operated, which I was fine with and so was Chantal. Neither of us had ever followed trends and had no desire to start now. What we were doing was working and if something ain’t broke, why fix it?

As for the New York stores, I loved to drop in when I could and do the window displays myself. Of course, like with everything else there was no budget to get fancy, which was never my style anyway. I’d look for anything decorative that caught my eye—like pills, for example. I could buy them in bulk in the wholesale stores that were all along Broadway in Midtown. A huge bottle of colorful capsules cost just five dollars, and it took only a few of those bottles to make a visual impact. I went to the Columbus Avenue store after closing, armed with only a hot glue gun. I stuck pills all over the window, scattered some on the floor, and even put them in all the mannequins’ hands.

My timing, in this case, could not have been more off. I have never been one who keeps up with news stories. If I had been, I would have known about something called “the Chicago Tylenol scare.” For those of you who are not old enough to remember the incident, in 1982 someone had laced bottles of Tylenol on the shelves of Chicago drugstores with cyanide. Seven people died, including a twelve-year-old girl. The incident spawned many copycats, leading to even more deaths.

Needless to say, my seemingly harmless and whimsical little window design didn’t go down well with anyone. We received letters, and customers were outraged. I removed the offending pills and made a mental note to stay on top of current events.