CHAPTER 26

The Vital Curves

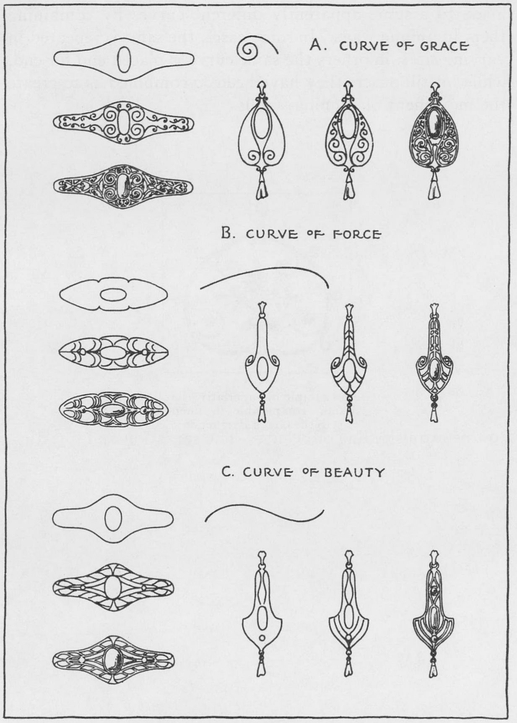

CURVED lines may be graceful, weak, or forceful, and varying or monotonous. Curves abound in nature from the humble plant to its most charming creations. We must select the lines which are most pleasing and fascinating to the eye in creating designs.

Human nature delights in variety and is intensely interested in change, especially when it occurs at varying intervals. Variety of action, work, and scenery often give buoyancy and spice to life. Human nature often craves for change; but if it occurs too frequently, we have a condition of unrest which is even more undesirable than monotony. The question arises as to how much change we can stand without reaching the point of abusing variety to such an extent that we cease to appreciate its value. This depends upon the physical and psychological conditions and upon individual differences. While the interest in a mere line does not depend on all three of the above conditions, it does rely on the aesthetic turn of mind and on temperament.

A line reaches its supreme beauty when it changes gradually with a slight increasing or decreasing variety for a certain length of its course and then makes a sudden and quick turn to the end. Such a curve is free, stimulating and graceful; it leads the eye slowly but surely for a considerable distance along a flat curve when it hastens the eye to the end with increasing and varying momentum. The changes in such a line often occur in a geometrical progression.

THE CURVE OF GRACE

The curve of grace, fig. A, page 225, may be made mechanically, by striking a series of arcs with different centers, but it can best be produced freehand with the sense of feeling as the only guide. Fig. A which typifies this curve was drawn as just explained. Nature has imprinted this curve on many forms; the nautilus shell is a striking example of wonderful grace. A careful study of the shell shows how this curve quickens its movement with increasing momentum as it winds toward the center. Here again we have exemplified an arithmetical progression of varying intervals of motion that pleases the aesthetic sense. Its graceful movement has been recognized as one possessing a supreme quality of beauty, hence its use in various applications. The Egyptians used it on their painted borders, the Greeks made extensive use of it in their decorations as a running border, the Romans employed it in their Ionic capitals and it was appreciated to such an extent as to find a happy combination with the Corinthian capital of the composite style. The Gothic craftsman of the 16th and 17th century found its ready application in iron and the precious metals. The iron grills, the large church door hinges, consoles in architecture and the metal attachments on wooden chests are but a few examples where the spiral found expression. In all the fine examples that have survived we find the spiral was executed with the utmost skill and perfection. The delicate acceleration of motion in each spiral is brought to the highest perfection in feeling and execution. The illustration on page 226 is as fine an example of a double branched volute curve in its application as can possibly be found anywhere; the acme of beauty. The curve of this ironwork should be studied and copied many times, nay, worked out in the metal before it can be appreciated. The goldsmith and jeweler of the guild made use of it in more ways than one. We find the scroll of many more turns in delicate filigree work. This is made possible by the softness of the gold or silver wire used. Oftentimes these spirals, making a double branched volute, are used in a series to make current scrolls.

THE CURVE OF FORCE

The curve of force, fig. B, page 225, occurs profusely in nature as a supporting element. Its seemingly straight part implies strength, it gives the feeling of being able to give great support. It is found in many plants, ranging from the blade of grass to the contour of the tall elms. It is the beautiful curve that the skyrocket describes as it leaves the ground in an almost vertical direction, increasing its curve to the top as it loses momentum, until from lack of force it quickly takes a downward direction producing the same curve once again in the reverse. The eye delights to follow it as it ascends high into the sky, not only because of the path it describes, but also because of the varying speed it generates. This curve is also to be found in the oval and the ellipse, but is absent in the circle. It will readily be seen that the circle lacks variety because, by reason of its sameness of curvature, any part of its circumference can be superimposed on any other part, hence its monotony of curvature. It continually changes direction; at every point on the circumference the change is unvarying since it eventually returns into itself. The curve of the circle is not a free curve as it is controlled by a center. It is seldom found in nature except in the cross section of stems, stalks, and tree trunks. Ruskin calls it the finite curve, while the free curve of the oval and the ellipse he designates as the infinite and immortal curve of beauty.

We find the curve of force used by the people of past generations; the Egyptians recognized it in the lotus bud, and papyrus, they found a direct application in their capitols; the Greeks showed their fondness for it as is evidenced by the contour of their vases, the antifix, akroter and in many other sculptural ornamentations. It did not escape the keen eye of the Romans, as we find it used profusely on their painted vases, their capitals, arches, and even their small common bronze utensils. The curve of force is capable of so much variation and offers endless possibilities. The ingenious designer can easily imagine the reverse curve of this line and make it readily applicable to many forms and contours. Such a line makes an “S” curve and by changing its proportions it can assume infinite variety as is shown on page 225, fig. C, it may assume such a perfection as to make what Nogarth regards as a curve of beauty.

THE CURVE OF BEAUTY

We have observed this line in the rolling hills of the country as they merge one into the other; we recall it in the upward sweep of active flames and in the rolling waves of the high seas. We find it throughout the contours of the human figure when in profile. The artist in recognizing this line of beautiful movement and fine proportion has not failed to use it in his own expression of thoughts and emotions. Master Painters like Giotto, Michaelangelo, and Titian, not only made frequent use of it as the main structural lines of their theme but the composition of a single figure or drapery was made to echo the movement. Corot made frequent use of it in a horizontal position. His points of attraction and general massing of darks cause the eye to move unconsciously in the path of such a curve. The grandeur of his whole composition is largely due to his success in making the elements conform to this exquisite line of beauty. The sensation and joy stimulated by the subtle movement of such curves can be likened to the rhythms of a great symphony.

It is the province of jewelry design to use anything that is grand and ennobling. Employing the most precious metals, bits of exquisite colored enamels, gems and pearls of the rarest specimen, it only seems compatible with the above to make use of the line of beauty as a means of unifying metal and stones. Thus the artisan may express his inner feelings and emotions in the mediums just mentioned as the artist does with paints, brushes and canvas. The jewelry craftsman, however, cannot use curves of an intricate kind if he would observe the use to which his product is to be put. It limits him to simple and restrained lines with a variety of the most subtle kind. Hence his sensitiveness to so fine a curve as herewith described.

The designs on page 225 show the application of these three fine curves in brooches and lavalieres. They have been made to assume apparently different curves by combining them in unique ways. In some cases, the same is repeated in varying sizes, in others the same curve is placed end for end, while in still others they have been so combined as to create the movement of running scrolls.

The use of these three curves give simple designs of good line arrangements and fine relationships

An example of superlative scroll design, comparable in fineness to the Greek Parthenon