CHAPTER 36

The Finger Ring

HISTORY tells us that wearing rings was probably introduced into Greece from Asia, and into Italy from Greece. Unlike today, in ancient times they served a two-fold purpose, ornamental and useful, being employed as a key or a seal, the latter being called “sphragis,” a name given to the gem or stone on which figures were engraved.

Long ago both sexes wore rings in profusion. At the close of the 18th century enormous rings were worn. The hand of a woman presented a good collection of rings. During this period the wedding ring was unnoticed on the fingers of women, being almost completely concealed by other wide and ornate rings. So important was ring production, therefore, that its manufacture was separated from the ordinary work of the goldsmith and was made, thereby, a trade in itself.

Today, as an ornament, the finger ring is the most common form of jewelry. The design is limited in shape and area. All rings have a point of attraction either in the stone or in the decoration, the wedding ring alone being an exception. The ring form is a device to display a stone which in turn adorns the finger. This fact makes the stone the main point of interest in this form of jewelry. Some of the Egyptian and Roman rings, consisting of plain bands of metal set with roughly cut stones with extremely little if any ornament, illustrate this point. As in all forms of design the ring must comply with the principle of fitness to purpose. The part of the ring that is on the inside of the finger must be narrow enough to cause no discomfort to the wearer while the top of the ring may be light or heavy as desired. The lines forming the sides of the shank should be simple curves, admitting slight modification. When ornament is used it should be subordinated to the stone and all other interest added as decoration should lead the attention from the shank up to the stone, if there is one, in a graceful manner with ingratiating effect. The stone should be the center of interest while the decoration on the shank and around the stone might well reflect its character. If the stone is light and delicate in color the design of the ring and the decoration should be in harmony with these qualities. The stone forming part of the metal band should be thought of as such in the process of designing. The method of setting it whether by prongs, gypsy, belcher, or in a box is determined by the nature and cut of the stone. A small stone of brilliant color can be made important if set in prongs, while soft stones may be set down into the metal in a gypsy setting, to protect the stone. Large and high stones should be set in elevation so that the gem and the ring assume a mirthful, sportive air.

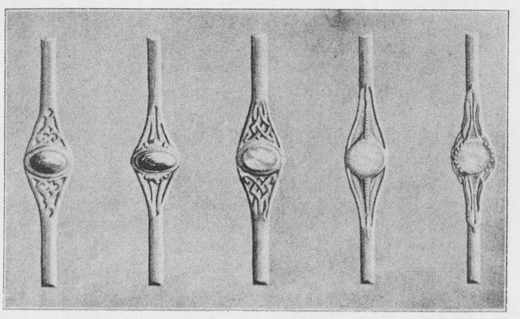

Finger rings designed in the blank

Illustrations on page 82 represent designs that can be executed by the amateur craftsman. The simplest modification of the plain band would be two or more saw-piercings on the shank, increasing in width as they approach the stone. Variations of these piercings should keep the vertical effect of the ring. Illustration on page 281 shows designs for casting and chasing. The same principles of design are involved here as in the pierced ring. We have in the first three designs an attempt to extol the qualities of the stone. The decoration is restrained and simple, neither overdone nor detracting from the interest of the gem.

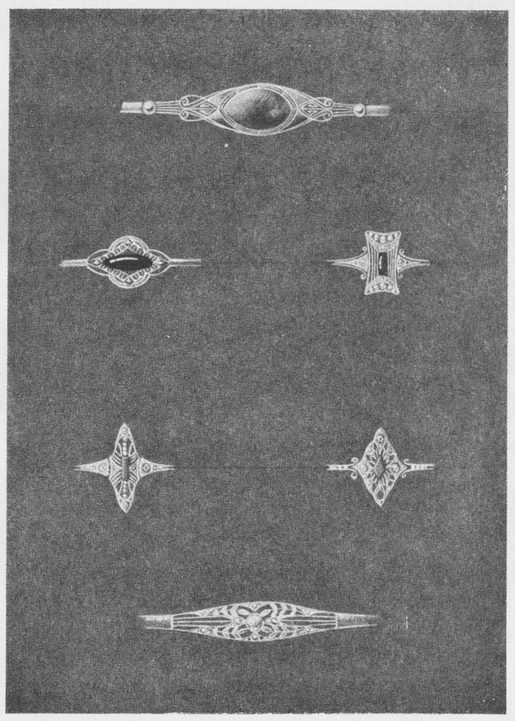

Platinum rings present a charm that is all their own. The color, hardness and rarity of platinum restricts its use. Hence, instead of the synthetic method of building on the ornament, or by carving, it is preferable from the cost standpoint to produce the design by perforation. Hence the very fine saw-piercings impart the effect of delicate wire work. When designing a platinum ring as those illustrated on the opposite page, it should be treated much the same as fine wire work.

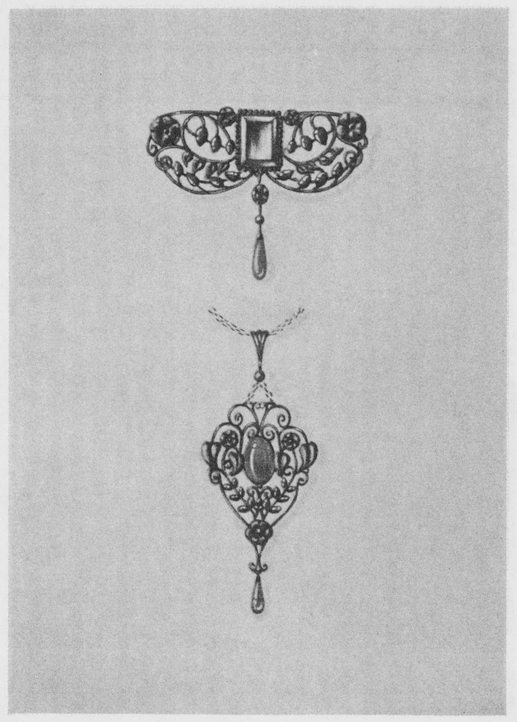

Platinum bracelets and rings designed with extreme delicacy

A leaf, a scroll, a few stones, skillfully and harmoniously arranged