I CALLED ZENDIK FARM WITHIN MINUTES OF READING THE AD. THE FIRST question I asked of the upbeat-sounding man who answered was about food and farming. I was standing in a guest bedroom that doubled as my dad’s home office. “I was wondering,” I said, wrapping the phone cord tight around my fingers, “what you mean by ‘organic farming.’ I mean … why organic food is important to you. To the cooperative.”

“You know what’s happening to the earth, right?” He was both patient and urgent. Before I could shape the thoughts and impulses I’d had over the past few years into a coherent answer, he continued. “The planet is dying. There are chemicals in our air and water, chemicals in our food. The earth is being destroyed and we’re trying to do something about it.”

I was floored by this: In the almost three years since I’d become aware of these issues, this was the first time I’d had a conversation with anyone who’d captured my fears and concerns in such direct language. “How?” I managed to ask.

“Showing the way,” he said. “Providing a model for the world of better ways to live, ways that are respectful, not destructive. We try to live in balance with the earth. We conserve our resources. We rehab and build our own houses from recycled materials; we compost our food and farm waste. Growing food is a big part of it—living off the land, leaving the soil better than we found it. All of us here cooperate, we help each other by communicating honestly, being real with each other. Have you read The Catcher in the Rye?”

I was shocked by this reference to one of my favorite books from someone who’d already put into words so much of what I’d been feeling. I saw Holden Caulfield as a hero in his stance against everything “phony,” conformist, and materialistic, and I kept a copy of the book beside my bed.

“We’re trying to be the catchers,” the man said, to “preserve innocence and idealism. That’s the only way forward.”

I was hooked, so wildly excited that at the end of the call I rushed into my parents’ room looking for my mom. I could hear the swish of water in her bathroom—she had said she’d be taking a bath—and though we weren’t any more comfortable with nakedness in my family than we were discussing sex or difficult emotions, I couldn’t contain my excitement. I knocked, and she called me in; she drew up her knees as I sat on the edge of the tub. It’s a testimony to the nurture and care that she’d given me that even as I was rejecting everything about her way of life, I wanted her help and approval in doing so.

“I’m so glad,” she said when I’d finished my breathless narrative about shared philosophies and The Catcher in the Rye. But after a brief pause, she followed with some practical questions that I’d known she would ask and that I’d managed to address before hanging up the phone: Where exactly was the farm located? (In the town of Boulevard, roughly seventy miles east of San Diego.) What exactly were the terms of the apprenticeship mentioned in the ad? (The apprenticeship lasted six weeks, for a cost of two hundred dollars for room and board.) But then she added a few other questions I hadn’t anticipated. “He said ‘commune’?” she asked. Communal was the word he’d used in describing the living arrangements, but he hadn’t contradicted me when I’d asked if by that he meant a commune. I’d heard the term several times growing up, most notably in the eighth grade during a workshop on creativity that had culminated in a student performance in which we all wore 1960s-inspired hippie clothing and played a recording of the Beatles’ song “Baby, You’re a Rich Man,” with its critique of materialism, to an assembly of well-coiffed, well-to-do parents, many of whom complained to the school board afterward. The word commune referred, I’d thought, to something from the past, a history lesson, a vanished way of life.

“ ‘Commune,’ ” my mother continued, “not ‘cult’?” This was 1987, less than ten years after the mass suicide and murder of more than nine hundred men, women, and children in Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple cult. My memories of the news stories about that horrific event were graphic enough that I realized I should, in fact, try to gather more information about Zendik before leaping into a potential abyss.

I ran to grab a blank legal pad from my father’s office and again perched on the edge of the tub, pen in hand. I scribbled down questions as my mother and I thought of them: Was Zendik Farm a cult? Would I be free to leave any time I wanted to? Would I be free to make phone calls any time I wanted to? Would my family be able to visit me? How far away were the nearest farms or houses? Some of these questions, we decided, I should look into myself, and some I should ask directly of someone at the farm. I headed off first to do research at the Winnetka public library, but I couldn’t find anything about Zendik Farm Arts Cooperative specifically in any card catalog or microfilm database. I did find what seemed to be useful information about communes in general. The dictionary definition appealed to me immediately—a group of people not all of one family sharing living accommodation and goods. This was what I most wanted—the possibility of finding a group with whom I could share everything, people who would understand my views and make me feel not as isolated and purposeless as I had often felt in Winnetka.

Communes in the United States, I read, actually dated back long before the 1960s: the Harmony Society founded a chapter in Pennsylvania in 1805; Brook Farm, a transcendentalist group in Massachusetts chronicled in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance, was launched in the 1840s; the Oneida Community in upstate New York, well known today for the silverware its members handcrafted, was founded in 1848. Though the social, economic, and religious beliefs of these groups varied, they shared in common the desire to build a utopia—a concept that dates much further back in time, to Plato’s Republic, written between 380 and 360 BCE, and Thomas More’s Utopia (the first actual use of that term), written in the sixteenth century. I thumbed through the dictionary to utopian and found what the man on the phone at Zendik Farm had described, what I’d been searching for ever since reading Walden and Siddhartha: advocating or constituting an ideally perfect state. One of the books I’d found contained a photo of a commune from the 1960s: a group of men and women in a desert-like setting dressed in clothes that had a vaguely Wild West, outlaw, pioneer look. Some of the men wore Davy Crockett raccoon caps, and the women all had long, flowing hair. They were young, tanned, and good-looking, all of them grinning with an air of ease and confidence that I craved for myself.

WHEN I MADE my second call to the farm, right after returning home from the library, I asked my mom to sit next to me—both to reassure her and to make certain for myself that I addressed all of our remaining questions. I was relieved that the same man from before answered—it hadn’t occurred to me that someone else might until I sat waiting while the phone rang for what seemed a long time. He responded patiently to my questions. Yes, I could leave any time I wanted; yes, I could use the shared phone in the main house any time; there were no close neighbors but there was a bus stop just a few miles away; family and friends were welcome to visit any time. “Look,” he said with a trace of humor as I reached the end of my list. “You sound like an intelligent young woman. It’s simple—if you come here and you don’t like it, you can leave. If you come here and you do like it, you can stay.” My mom squeezed my hand and nodded okay to indicate that she didn’t have any other questions.

Over the next few weeks, I felt a newfound sense of purpose as I made arrangements to go—packing up my neo-hippie clothes, picking out which books to take with me, buying the plane tickets my father insisted on making round-trip. My mother and I came up with an escape plan “just in case”: If I arrived and didn’t like it—if I had any reason to think that it was, in fact, a cult—I’d call my parents and start speaking French. Though none of us knew more than the basics, they’d know I was signaling trouble, and they’d arrange for some close friends of theirs who lived in San Diego to drive out immediately (with the police if necessary) to get me.

But from the moment I set foot on the farm, I felt certain our precautions weren’t needed. Just as I’d hoped, the thirty or so Zendik members—most of them, like myself, in their late teens and early to midtwenties—shared my concerns about the environment. We discussed these concerns at length in impassioned conversations over shared dinners of fresh-grown organic vegetables and farm-raised meats in the high-ceilinged dining room. “Jacques Cousteau says the oceans are dying,” someone would say, “and American culture responds with The Love Boat.” “One hundred unique species of life are being lost a day,” someone would say, “and nobody’s even paying attention.”

I felt a new kind of closeness not only to the group, but also to the natural world as I immersed myself in the hands-on work of gardening. Zendik Farm’s property encompassed seventy-five acres that were located less than ten miles from the Mexican border to the south and from the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park to the northeast. Much of the property was wilderness, marked only by narrow hiking and riding trails with stunning views of desert washes, wildflowers, rock formations, and boulder-strewn mountains and canyons, as well as fleeting glimpses of wildlife, including rattlesnakes, turkey vultures, coyotes, mule deer, and red-tailed hawks.

The farm was accessed by a narrow dirt road that led up from the entrance off a main road. The first part of the property visible on the two minutes’ drive in were the vegetable gardens where I spent most of my days—two acres of wide, raised rows and standalone patches for asparagus and berries, all of it interplanted with colorful sunflowers, tithonia, marigolds, and cosmos. Beyond that was the arched entrance gate with the Dante quote, and past that, large flower beds bordered by rock walls, then the living quarters—four Quonset huts painted with bright murals, and an old rehabbed farmhouse with a glass addition made from recycled materials. Beyond the farmhouse there were several barns, enclosed paddocks, and pastures for the Alpine and Nubian goats we bred and kept for dairy, draft horses, donkeys that had been airlift-rescued from Death Valley, chickens, and turkeys. The donkeys had not been native to Death Valley; they were brought there by miners and prospectors seeking their fortunes in the early 1870s. Over the years, burros escaped or were turned loose. They adapted well—too well—to the environment. As their numbers increased, burros impacted the springs, vegetation, and the landscape through their proliferation of trails. They were airlifted out by the Fund for Animals, which was founded in 1967 by prominent author and animal advocate Cleveland Amory. The donkeys had a good life on the farm, amid other rescued and domesticated animals. Dogs and cats roamed freely, along with several geese and assertive peacocks. Louie fit right in until she disappeared after we were at the farm for about a year. We assumed she’d been eaten by coyotes. We often heard coyotes howling at night, and cats had died that way.

There were two outhouses (the house had running water and a bathroom, but we generally used the outhouses as they were more environmentally friendly), and a materials storage area (a junkyard, really) where old machinery and recycled materials such as bricks, boards, and glass from tear-downs were kept until they could be used in other projects.

The leaders of Zendik Farm liked to change locations roughly every five to ten years for reasons that I never clearly understood. They said they were seeking out a more comfortable climate and more fertile farmland; there was also the practical economic consideration of selling a property that had grown in value and buying more affordable land elsewhere, as well as the loftier stated goal of spreading the Zendik way across the country. With every move, it was hard to leave the land we’d come to know so well, and the buildings we had rehabbed and constructed by hand, but the new locations were always beautiful.

We moved from California to Texas in 1991, in a rickety caravan of dozens of trailers filled with animals and farm equipment. The new property was located in Bastrop, thirty miles outside Austin. Its three hundred acres afforded a beauty no less stunning in its way than that of the California farm. It was bounded on two sides by a U-shaped bend in a river that we often swam in to escape the intense heat; the shade trees and coolness of this spot had, in earlier centuries, made it a watering hole for buffalo and a favorite hunting ground for Native Americans. The surrounding rural countryside was lush and green, with rolling hills, woods, and lovely fields of bluebells and other wildflowers. We expanded the farming operation in Texas to include several different types of grain—field corn, oats, triticale, spelt, and millet—for a total of roughly two hundred cultivated acres. We also expanded the barn area and added more goats, bringing the total to sixty, plus a few dairy cows and pigs. The uncultivated parts of the property were rich with sprawling centuries-old pecan trees, and in the fall all of us would gather overflowing buckets of the ripened nuts.

The North Carolina property, where we moved for the milder climate in 1999, was a 116-acre farm that had been in the same family since the 1800s. It was located about forty-five miles outside Asheville in the town of Mill Spring. The farm’s specialty had been sweet potatoes—a crop, like blueberries, that thrived in the high acidity of the native soil—and in addition to an old barn and a nineteenth-century Appalachian farmhouse with a porch built on piles of craggy rocks, there were two potato-curing houses (sweet potatoes need to sit in a well-ventilated space at 85 to 90 degrees for two weeks after the harvest), all of it tucked into a lush valley with a creek running through it. We built several new structures, including a large cob kitchen and dining hall and a free-form log cabin with enormous windows. From the gardens where I worked I had an unobstructed view of a cluster of mountains that were part of the Great Smokies.

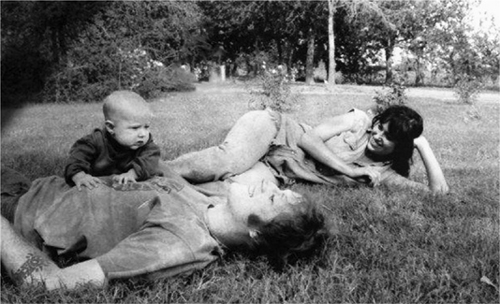

HANGING OUT AT THE FARM IN TEXAS (photo credit 4.1)

In my seventeen years at Zendik Farm, I learned more about growing organic food than I ever could have hoped to. Starting with my initial experience tentatively harvesting snap peas on my first day in California, I learned every step of the farming process through hands-on daily work: hauling huge piles of barn muck to the compost pile to preparing large barrels of “compost tea”; enriching the soil with kelp meal, gypsum, colloidal rock phosphate, and other amendments; planting wide varieties of vegetables and discovering which combinations of plants worked best together (basil planted among tomato plants attracts beneficial insects that prey on hornworms, for example; dill or fennel planted with members of the brassica or cabbage family repels cabbage worms and loopers; castor bean plants repel gophers; tomatoes and potatoes should not be planted next to each other as they’re both in the nightshade family and become more vulnerable to pests in close proximity); tending; and finally harvesting.

I learned the value of “green manure”—of planting cover crops such as alfalfa, clover, hairy vetch, and winter rye, which are then worked into the soil, to enrich it with nitrogen, improve its texture, and discourage weeds. I learned how to build cold frames, also called low tunnels, to add five to ten degrees of frost protection and extend the growing season for vegetables such as spinach, lettuce, kale, and chard, attaining year-round growth for those crops in California.

I learned other, broader lessons about organic farming as well. My friend Kare was in charge of animal husbandry, and I learned from her how to make herbal poultices and mixtures of carrot juice and molasses to help tend to sick goats. I spread feed for the chickens and held them for butchering, learning the hard way to hold very tight in order to keep them still and prevent their running around after Kare delivered the death blow to their necks. I also learned how to defeather and gut the birds. I helped rehabilitate animals that had been injured. I learned how to milk goats and how to make the kefir that was one of our main sources of dairy. And I learned the most basic and sweat-inducing of farm tasks: how to muck out a barn without throwing out your back. We grew grapes, strawberries, raspberries, and blackberries, and I learned the names of fruits I’d never heard of before—cherimoya, sapote, and guavas—and the best ways to harvest them. In California, we drove out to the orchards and organic farms around San Diego to gather those fruits, as well as figs, pomegranates, persimmons, apricots, and other fresh-picked, sun-ripened delicacies that astonished me with the depth and intensity of their flavors.

Though our ideal was to be entirely self-sustaining, we weren’t able to grow all of the organic grains, beans, and herbs we needed ourselves, so we sourced those products as locally as we could—for the cost savings as much as for environmental reasons, researching to find the local and regional suppliers for the nearest Whole Foods or other health food stores and making arrangements to order in bulk. Our diet included some goat meat, from the young male goats butchered on the farm (that was one task I chose to sit out); some red meat we ordered in bulk; the chickens that we raised and butchered; and some fish we ordered whole from area suppliers. We kept bees, and sweetened fresh-baked goods with our own honey. Overall, in the height of the gardening season, our diet consisted of roughly two-thirds foods we grew or raised ourselves, though in the winter that number might fall to as low as one-third.

The shared task of cooking was one of my favorite parts of communal life, with different individuals and small groups rotating through a loose schedule. I often made chicken soup from scratch with my friend Kare, boiling the bones to make a rich broth, and huge stir-fries out of onions, carrots, broccoli, greens, tofu, and ghee, as well as big heaping bowls of tossed salad. By the time we moved to Texas, I was in charge of one or two dinners a week, working closely with two other people who’d help with the prep. Though the meals themselves eventually became a source of great pain and friction—they developed into a forum for group criticism of members, like me, who violated the commune’s often unspoken rules—in my first days, months, and even years at Zendik Farm, throwing myself into the work and shared rhythms of daily life, I felt that I’d finally found my true home. I clung to that feeling far longer than I should have, long after my doubts and frustrations had started to outweigh it.

——

TWO MONTHS AFTER MY RETURN to Winnetka, the garden I had planted in my parents’ backyard was finally coming to life. After days of waiting and miles of walks with Thea in her stroller, I finally spotted sprouts from the second round of seeds we’d planted when the first had failed. Thea marveled at the arrival of the new green shoots, which gave way over time to thicker stalks and spreading leaves, bright splashes of flowers, gradually swelling fruit, and ultimately an abundance of plant life in that enclosed space that I hadn’t anticipated. I was used to the farm’s more spread-out growth, but here everything was condensed—it was a veritable mutiny of peas, cucumbers, melons, eggplants, berries, green beans, sweet and jalapeño peppers, squash, pumpkins, red onions, lettuce, spinach, kale, and chard, bordered by mammoth sunflowers, cosmos, and zinnias.

Thea and I began tending the growing plants. I applied “side dressing,” gently raking in additional fertilizer from the mix of kelp meal, bone meal, blood meal, greensand, and dehydrated manure that I’d prepared before planting to help boost nutrients and growth. I did this in particular for the eggplants, tomatoes, and peppers, which tend to have longer growing periods and therefore a higher likelihood of depleting soil nutrients. I also practiced foliar feeding—spraying liquid organic fertilizer directly onto the leaves (plants can absorb nutrients not just through their roots but also through their leaf pores) roughly every two weeks, always spraying in the early morning or late evening, when the pores were more receptive and the leaves less vulnerable to scorching from direct sun.

At the farm, the use of foliar feeding and side dressing to boost soil nutrients had been so effective that in California, in what were essentially desert conditions, we’d grown a field of corn so tall it might well have been in Iowa. There, I’d mixed up batches of “compost tea” and “manure tea”—water in which I steeped giant bags of compost or manure. To make the tea, I would fill fifty-five-gallon barrels with water and add fresh compost or manure in burlap sacks that functioned as huge tea bags, using a ratio of roughly two parts water to one part compost or manure. I would remove the burlap sacks after three to five days and then spray entire rows of leaves with the “tea” from a five-gallon sprayer strapped to my back. I didn’t need as much fertilizer for my parents’ small garden, and the mixing process itself would have been too messy, so instead I used a store-bought concentrate of fish emulsion and seaweed that I diluted and sprayed on the plants.

The work in my parents’ garden was energizing. It wasn’t just the physical labor that invigorated me. I was also glad to have something with tangible results to focus on, something outside of my mind’s swirl of anxieties. And I loved watching Thea enjoy the garden as it grew. In the beginning she walked and crawled around the “baby” plants; eventually she was looking up to observe the vining plants and flowers as they grew taller than she was, stretching her arms up high toward the tops of the green stalks as they unfurled beyond her reach.

The spinach and lettuces—green and red oak-leaf, freckles romaine, and butterhead lettuce—were the first foods ready to be harvested, and in early June, right before dinner one evening as my mom finished setting the table on the terrace, I pulled off enough leaves to fill a large bowl. I hurried inside to soak them in cold water, “hydro-cooling” them, a technique I’d learned to keep lettuce crisp and fresh. I mixed a simple dressing I’d learned to make on the farm—apple cider vinegar, nutritional yeast, tamari, and olive oil—and after drying the leaves, I tossed it all together in a bowl. My father in particular loved it, and I felt gratified when he went back for seconds.

The air was starting to cool as we finished eating; my mother had brought out a jacket for Thea, who sat in my lap. Feeling Thea resting against my chest and looking at my parents as they sat relaxed in their chairs, breathing in the air that carried the heavy scent of earth and vegetation from the garden, I felt something close to happiness for the first time since I’d been home. “I can’t believe I’m actually here,” I said. “With you …” My voice caught.

“I can’t, either,” my father said. “We never imagined this.” My mom nodded, smiling back at me, and I felt in that moment that she understood—they both understood—that I was talking about more than just this moment: that I meant the ways they had supported me all along, and how the path I’d followed when I’d left was the one that had ultimately brought me back home.

AS THE BACKYARD GARDEN yielded more and more food, I started to regain some of the weight I’d lost, feasting on fresh tomato and cucumber salads, grilled eggplant slices, and berry smoothies. I was sleeping somewhat better, too, and finally felt strong and rested enough to answer some of the phone messages left by childhood friends who were still in Chicago, including Pammy Swartchild and Mollie Karger, friends since nursery school who’d heard of my return through the inevitable small-town information network. My relationships with my friends from Winnetka had become strained over the previous seventeen years. Some of them had tried to stay in touch, writing letters and occasionally calling. Mollie had even visited me once in Texas. My sister, Hallie, had been the most persistent in staying in touch, calling regularly and visiting whenever she could at all three locations. But the commune’s leaders implicitly discouraged too-close contact with anyone who didn’t live there.

Family and friends were always “welcome” to visit at the commune, but the leaders—Arol, a former actress in her forties, and Wulf, a failed sometime beat poet and novelist in his sixties—insisted on passing the final judgment on everyone and everything. Visits from friends and family would often be followed by Arol and Wulf’s “honest,” supposedly definitive commentary. My father was dismissed as “Daddy Warbucks”; my mother as a “typical guilt-inducing mother.” Outsiders who didn’t share the commune’s bohemian aesthetic were labeled “uptight” and (the commune’s ultimate insult) “square.” These comments pained me, but I didn’t voice my objections because there was so much I loved about my life there, and I understood from early on that if I directly crossed the leadership, I would be forced to leave.

Even minor disagreements could cost you. Arol played favorites among the group’s members, giving and pointedly withholding her approval. For my first year or so, after Arol had welcomed me on my first day, I had very few one-on-one interactions with her. But on the night I received my dad’s phone call telling me that Mark had killed himself, Arol, who had heard the news, invited me upstairs to the suite that she and Wulf shared in the main farmhouse.

Their space had the feeling of a private zone or sanctuary: People entered only by invitation. I walked upstairs with a sense of occasion. Arol and Wulf each had their own bedroom, next door to each other just past a small seating area at the top of the stairs. Beyond that, there was another bedroom and a small kitchen with a wall of windows looking out on the breathtaking high desert scenery. The décor was more bohemian than hippie—dark-toned couches with bright, multicolored throw pillows covered in Indian prints. On the kitchen walls was a collage of pictures, including multiple photos of Arol when she was an actress in her twenties in Hollywood (she’d had a minor role on the 1960s TV show Petticoat Junction)—dramatic, beautiful images capturing the full force of her charisma, which, I thought, had only grown since then. There was a photo of a beatnik Wulf from the late 1950s, working at his old-fashioned typewriter while living on the Left Bank in Paris. There were other pictures from the early days of Zendik Farm, which had been started outside Los Angeles in 1969 as a commune for young artists, primarily musicians, who wanted to “drop out” of mainstream society. The photos showed people with long hair and dresses, large floppy hats, hand-carved instruments, and a classic sixties school bus painted dark purple. Drugs had been a big part of early farm life, and during the first decade of Zendik Farm, its members were “raw fooders,” eating only vegetarian, uncooked foods. By the time I arrived in 1987, the drug use was waning and the group had incorporated cooked foods and occasional meat. A few months after my arrival, the group decided en masse to collectively quit smoking both marijuana and tobacco and to wean themselves off caffeine and alcohol in order to be healthier and more productive.

Arol’s room was long and narrow, with a wall of windows looking out toward the rocky outcropping of Rattlesnake Mountain. Its most unusual feature was a claw-footed bathtub set along the opposite wall from the queen-size bed. There was no bathroom upstairs, but there was running water both to the kitchen and that tub; on later occasions, I’d talk to Arol as she bathed, with an ease and comfort with her body that was quite different from how I’d been raised. That night, Arol wore a handmade lightweight poncho-type top with loose-fitting pants; Wulf wore the patchwork bathrobe he often wore even during daylight hours (because of his emphysema and chronically bad health, he rarely left their living suite). We didn’t talk directly about Mark’s suicide, but I knew that was why they’d invited me upstairs. Their invitation meant a great deal to me. It was a mark of acceptance and approval, a sign that they were drawing me closer. They talked about the weather and the harvesting tasks to be done the next day (it was September, and there was a large amount of work ahead) and about their dogs (they always kept at least half a dozen, unleashed and forever jostling around the farm and their suite). They spoke with a kind of familiarity that made me feel at home. Arol and Wulf seemed to share my belief that the wider world was false, materialistic, destructive to the earth, and inauthentic. The word zendik, I’d learned shortly after my arrival, was Sanskrit for someone who was a heretic or outlaw, someone who did not follow the established order. These people were doing the very thing I believed had to be done to make the world a place where creative people like Mark would choose to live.

I don’t remember what I said in our conversation that night, but soon afterward Arol drew me closer and began giving me more responsibility—not only in the garden but also on the business and activist side of the farm’s operation. I was proud that she had seen something in me, but I was also aware that there was a dark side to her praise. Of all of Zendik Farm’s unwritten codes, one of the most pervasive was eschewing privacy. The only phone we could use for personal calls was located in the living room, the farm’s central social gathering place. We were almost never alone when talking to friends and family, and we felt constantly monitored: Any excess of warmth we showed to an outsider was taken as proof that we valued the wider world too much and weren’t fully committed. There was always bound to be someone listening who would pass on news of any questionable behavior to Arol, whose playing favorites encouraged competition and a certain amount of backbiting. I was criticized so sharply for the particular warmth I showed Hallie in phone calls (“Maybe you’d be more comfortable back home in Illinois with her”) that over time I called Hallie less often, and toned down my enthusiasm in conversations with her and other outsiders. Eventually, my friends stopped calling.

AROL AND WULF’S “TREEHOUSE,” ZENDIK FARM, AUSTIN, TEXAS, 1995 (photo credit 4.2)

I WAS SORRY FOR the distance I’d allowed to grow between us, but when I called Mollie Karger back not long after my return home, she dismissed my concerns and invited Thea and me to a gathering of friends and their children at her home in Chicago. Pammy and her children would be there, as would Joanne, a friend of ours since fifth grade who was visiting from New York.

Mollie lived in a contemporary house she’d designed in the city’s Lakeview neighborhood. The forty-five-minute drive from Winnetka took us down Sheridan Road and then to Lake Shore Drive, past the glittering sweep of high-rise apartments and office buildings overlooking Lake Michigan. After so many years of living in rural locations, I felt uncomfortable in that steel and glass landscape, which made me all the more nervous about facing my old friends. My mother, whom I’d asked to come at the last moment, pointed out the lake and bright-colored sailboats to Thea with determined cheerfulness.

If Mollie and the others were surprised to see my mom with me, they didn’t show it. Mollie smiled excitedly when we arrived, and Pammy and Joanne jumped up from the couch to hug us. Thea shyly clung to my legs as they greeted her, and clung still tighter when Mollie rounded up the children to introduce them. “She just needs some time to warm up,” I said apologetically.

I pulled Thea into my lap as I sat down on the couch. Mollie led the conversation as Pammy and Joanne joined in, trying to include me as though I’d never left. No one asked me any intrusive questions or spoke to me in a tone that implied there was anything unusual about my life or current situation. There was no way they didn’t know that I was back home living with my parents, and that my once vaunted ambitions hadn’t turned out as planned. But everything about their ease of manner and light, casual tone was intended to show me that I wasn’t judged by them for any of it—that I was accepted.

Their good intentions left me feeling almost worse than if they had been appraising or skeptical. They weren’t judging me, but I’d been judgmental of them during all my years away; I’d viewed myself as superior, a “warrior for the cause” of saving the world. And while my own life had been unraveling, they’d been accomplishing tangible things: They all had careers, husbands, houses, and resources, as well as an air of confidence about their choices and in themselves that I lacked.

After we’d been there a short while, Mollie rounded up the kids to head downstairs to a playroom. They were all happy to leave the adults, barely bothering to look back at their mothers—except for Thea, who shook her head fiercely.

“It’ll be fun, sweetie,” I assured her.

“No!” she cried out.

“It’s okay,” I said. “Look, the other kids are all going.”

She shook her head again, clinging to my leg and repeating, “No!”

“Mommy will be right here.”

She started crying loudly, angrily, and I scooped her up, giving an apologetic smile to my friends as I headed down to the basement playroom with her. She quieted when she saw I wouldn’t leave, gradually letting herself be drawn by one of the older children into playing with a set of blocks.

I found myself upset, not by Thea’s behavior in itself—she’d rarely let me out of her sight since we’d been back—but by what I was worried my friends thought of me as a mother. A bad mother—that had been one of the sharpest criticisms I’d faced at Zendik Farm, a phrase that still echoed in my mind. On the farm, parents were sharply criticized when their children acted out. It was considered a reflection of the parents’ own emotional dysfunction. Children were expected, as soon as they could, to work alongside adults, doing everything from tending the gardens and animals to cleaning and cooking. Anthropologically, the theory went, this was how early humans developed; only in modern civilization did children come to be spoiled and coddled away from their natural state.

Most crucially, parents were discouraged from having “too close” bonds with their children. It was for my bond with Thea that I’d received the harshest criticism. Although parents were always held accountable for their kids’ behavior, children were seen as the children of everyone in the group; close parent-child bonds were believed to interfere with the child’s bonding with the community as a whole. In retrospect, after reading about the attitudes toward child rearing both of early experiments in group living like the Oneida community and later arrangements such as kibbutzim, I’ve come to understand that these beliefs are not unusual for such groups. But at the time, I took very personally the criticism and punishment I received for the close connection I’d formed with Thea, including my “exile” to the cabin with her. And whatever the logic of or justification for the punishment, it just did not work for me. Nothing changed my behavior. From the moment of Thea’s birth, I felt an intense love for her and couldn’t hide my strong desire to hold her or the fact that my eyes went first to her in any group or room. She was mine, and no well-intentioned or wrong-headed theory could or would change that.

Even before she could talk, Thea had also resisted efforts by commune members to interfere with our bond. Each set of parents had a small cadre of about six people on the farm, mostly younger women, who would regularly help take care of a baby or toddler. By the time she was about ten months old, Thea could identify our group caretakers and, when she saw them approach, would thrust out her hand in rejection while uttering a defiant shrieking sound. She often refused to quiet down until I’d carried her away.

My mother sought me out in Mollie’s basement playroom. Reading my mood, she gave me a reassuring squeeze on the shoulder. “Thea’s just moved halfway across the country,” she said calmly. “She just needs time.” For all the progress I felt I’d made since coming home, I realized that I needed time, too.