CHAPTER ONE

Mash Up in the Mother Country

Calypso, cold winters and a black ballet company

WHEN CALYPSONIAN LORD KITCHENER stepped from the gangplank of the SS Empire Windrush at Tilbury, on 22 June 1948, he barely had a chance to feel Mother England beneath his feet before a microphone was shoved into his face. The coterie of English reporters waiting for the five hundred new arrivals from the Caribbean knew to look out for this imposing, snappily-dressed figure, whom they’d been told was a bit of singer. Never one to pass up an opportunity, Kitch, unaccompanied and apparently ad-libbing, broke into song:

‘London, is the place for me

London, this lovely city

You can go to France or America, India, Asia or Australia

But you must come back to London city …’

Captured by Pathé News, against the rusting hull of the former troopship, this cheerful, assured performance of “London Is The Place For Me” is still dusted off as an easyfit encapsulation of the start of mass immigration from the Caribbean into the UK. And, indeed, of the immigrants themselves – happy-go-lucky souls, never too far from spontaneous song. Neither assumption is particularly accurate. Not entirely the carefree, spur-of-the-moment songster he might seem, Kitch was already a big star all across the Caribbean, and had written the song during the four-week voyage for exactly this moment. For that matter, West Indians had been present in London in significant numbers since the First World War, while the Windrush itself had brought over a considerable number of Jamaican settlers the previous year. Kitch and fellow Trinidadian calypsonian Lord Beginner made the decision to pay the £28.10s passage on the Windrush precisely because they knew there was a healthy African-Caribbean music scene in London, and they could find a relatively wealthy black audience.

As a symbol of specifically musical immigration into the UK, however, Kitch’s quayside concert is priceless. For a calypso so vividly to reference the capital was a defining moment. This wasn’t simply music performed and consumed in Britain, on a strictly insular level, by immigrants and reverent aficionados; it was music that while remaining faithful to the Caribbean was adapted to fit its new setting, and found itself in a creative environment that was prepared to make efforts to accommodate it. Much like the passengers on the Windrush, who came in, got their feet under the table, got to know the neighbours, and mixed it up a bit with them. One reason the ship has assumed such significance is that 1948 marked the start of the process whereby Caribbean immigration made a cultural impression on the UK, as arrivals began to see the country as a long-term home. While staying true to who they were, they were changing how they did things, and the world in which they found themselves would never be the same again.

WHEN DISCUSSION TURNS to West Indian musicians who were active in London before the dawn of ska, the story usually begins with the beboppers of the 1950s: the likes of Joe Harriott, Wilton Gaynair, Harry Beckett and Dizzy Reece. Caribbeans had, however, been at the forefront of British jazz for almost as long as British jazz itself. Their influence is one of the great untold stories of the London scene of the 1930s and 1940s. By adding elements of their own countries’ music, players from the colonies were responsible for much of the originality in early British jazz, which otherwise, essentially, imitated jazz from the US.

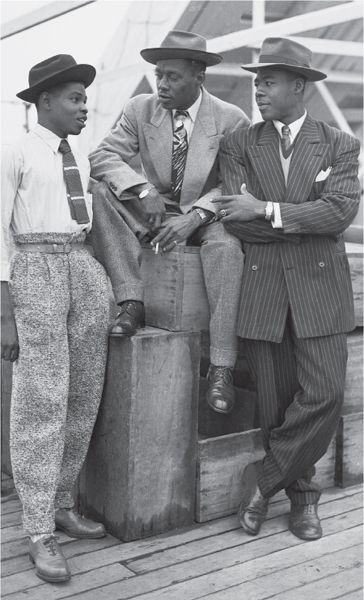

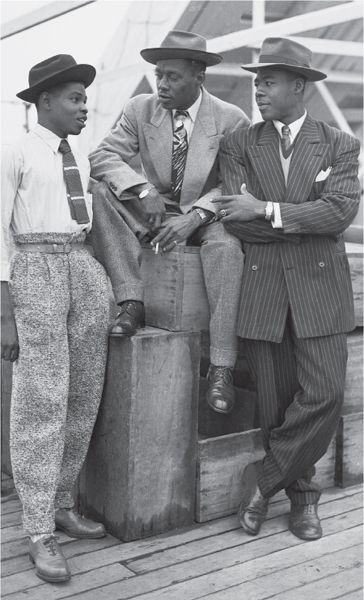

In 1948, passage on the Windrush from Jamaica to the UK cost £28.10s; the voyage has come to symbolize the start of mass immigration from the Caribbean. From the left, passengers John Hazel (21), Harold Wilmot (32) and John Richards (22) lead a style offensive on the capital.

The very first black band to make its mark in the UK, the Southern Syncopated Orchestra, brought West Indians into the British jazz world in 1919. Put together by composer Will Marion Cook in New York the previous year, the 27-piece African-American band arrived in London to fulfil long-term contracts first at the Philharmonic Hall in Great Portland Street, and then at Kingsway Hall in Holborn. Along with the all-white Original Dixieland Jazz Band, who came from the US for an extended stay at around the same time, the SSO can be credited with introducing jazz to the UK. Such was its quality that it included operatic soprano Abbie Mitchell, pianist/conductor Will Tyers, and clarinet legend Sidney Bechet – who first encountered the soprano saxophone in London, seeing one in the window of a Shaftesbury Avenue music store and buying a specially modified version.

This versatile black band made an immediate impression on straight-laced Edwardian London, then recovering from the First World War. The Prince of Wales, later Edward VIII, invited the SSO first to play at Buckingham Palace, and subsequently to headline a grand ball at the Albert Hall to mark the first anniversary of Armistice Day. With demand high, the band stayed on beyond 1920. Over the ensuing years, its original American members drifted away, to be replaced by London-based musicians who hailed from Barbados, Guyana, Trinidad, Jamaica, Antigua, Haiti, Sierra Leone and Ghana.

During the 1930s and 1940s, London’s better swing and rhumba bands were either entirely or largely West Indian – even if these British colonials frequently pretended to be Cuban, because the most fashionable dance rhythms came from the island. More than one musician of the day has maintained that Caribbean players were sought after for their trademark combination of exuberance and discipline, vital for the very swinging-est swing – a trait that later manifested itself in ska. Above all, though, as citizens of the British colonies these black players had the right to work in the UK, whereas from 1935 onwards the Ministry of Labour made it difficult for US musicians to get permits. UK bandleaders could thus pass them off as Americans, thereby greatly increasing a band’s glamour factor at a fraction of the cost of the real thing and with minimal bother.

A veritable flood of Caribbean musicians were therefore flowing into London long before the Windrush hove into view. Big bands like Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson and his West Indian Dance Band, Frank Deniz and his Spirits of Rhythm, and Leslie ‘Jiver’ Hutchinson’s All-Coloured Orchestra were in huge demand for ballrooms and wireless broadcasts. As both musician and socialite, the smooth, well-spoken Hutchinson was a particular favourite of the aristocracy. It was not unusual for him to accompany the hard-drinking Prince of Wales back to York House in the early hours to continue carousing. Recordings by the higher-profile early British black bands can be found on Topic Records’ anthology, Black British Swing.

At the same time, any number of small groups, pick-up bands and informal, shifting house bands were appearing in nightclubs of all sizes, all over London. Besides such well-known venues as the Café de Paris in Coventry Street, the Florida Club in Bruton Mews, the Embassy Club in Mayfair and the Hammersmith Palais de Danse, the West End also held a remarkable number of black-owned establishments, even before the Second World War. Soho was home to the Caribbean in Denman Street; the Nest in Kingly Street; and the Fullardo, and later the Abalabi and the Sunset, in Carnaby Street. Just outside, and somewhat tonier, were Edmundo Ros’s high-society haunt the Coconut Grove on Regent Street, and the Paramount Ballroom in Tottenham Court Road, under the apartment block Paramount Court. The latter is now an upmarket strip joint, but back then it was a big plush ballroom, owned by a Jamaican immigrant.

At the Royal Albert Hall, in 1942, Guyanese conductor, composer and clarinettist Rudolph Dunbar became the first black man to conduct the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

ARGUABLY THE MOST NOTEWORTHY of the pre-war West Indian influx was Guyanese clarinettist Rudolph Dunbar, who arrived in 1931. Dunbar had studied his instrument at Columbia University’s Institute of Musical Arts (later renamed the Juilliard) in New York; was involved in the Harlem jazz world of the 1920s; learned conducting and composing from Phillipe Gaubert and Paul Vidal, respectively, in Paris; and had been taught classical clarinet by Louis Cahuzac, considered the world’s leading soloist of his time. Once settled in London he fronted his own dance orchestras – the All-British Coloured Band and the Rumba Coloured Orchestra – and played alongside fellow Caribbeans including Cyril Blake, Joe Appleton and Leslie Thompson. As a sideline, he became the first black man to conduct the London Philharmonic when he led them in front of seven thousand people at the Royal Albert Hall in 1942. Dunbar also conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in 1945, and conducted in Russia, the US and Poland. Whenever he could, he’d perform works by black composers.

Being Guyanese, however, Dunbar was in the minority among London’s overwhelmingly Trinidadian musical contingent. Because Trinidad had its own unique music scene, centred on calypso, its players tended to be more evolved. Double-bassist Al Jennings came over in the 1920s, and led his own bands through the 1930s and 1940s, most notably at the Kit Kat Club in the Haymarket – in the basement of the building that until recently housed the Odeon cinema – and at the Hammersmith Palais. He returned to Trinidad after the war, where he formed the All-Star Caribbean Orchestra, only to bring them back for a long-term residency in London in 1947.

Clarinettist Carl Barriteau moved to London from Trinidad in 1937, and played with bandleader Ken Johnson. After Johnson was killed when a German bomb scored a direct hit on the Café de Paris in March 1941, Barriteau, who suffered a broken arm in the incident, formed his own West Indian Dance Orchestra. As well as entertaining British troops on ENSA tours, he performed nightclub and variety-hall gigs, and broadcast extensively on BBC radio.

Sax man Freddy Grant, who also arrived in 1937, made quite an impact on London. He was Guyanese, but might as well have been Trinidadian, having spent a long time in jazz and calypso orchestras on the island. After playing jazz with Appleton, Dunbar, Blake and Hutchinson through the 1940s, he prospered with his own bands, including Freddy Grant and his Caribbean Rhythm, Freddy Grant and his West Indian Calypsonians, Frederico and the Calypsonians, and Freddy’s Calypso Serenaders, many of which employed the same personnel. During the 1950s, while working the calypso angle in dancehalls, the supremely talented Grant hooked up as a sideline with Kenny Graham’s Afro-Cubists. He also formed a partnership with Humphrey Lyttelton as the Grant/Lyttelton Paseo Jazz Band, recording calypso-ish takes on jazz and blues favourites.

Acclaimed Nigerian composer Fela Sowande provides a vivid example of wartime London’s cultural melange. The acknowledged founding father of Nigerian classical music, a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists and choirmaster at Kingsway Hall, he could be found duetting with Fats Waller on the piano in London clubs, and was a regular in Grant’s bands, playing calypso to audiences who assumed he was West Indian.

BETWEEN THE LATE 1920s and the mid-1940s, a black intelligentsia started to find traction in London. The city became a gathering point for African and West Indian students, professionals and political dissidents. Organisations like the League of Coloured Peoples, the West African Student Union and the Union of Students of African Descent all set up shop, exchanging ideas and experiences from around the world. Much of what was discussed in London was to influence the break-up of the British Empire. Groups in the capital maintained strong links with nascent trade unions in the colonies, and many who studied in London attained political office on returning home. There was also a considerable degree of interplay between the black students and the English intellectual hipster-types who were to become the beat generation. Soho became one of the very few genuinely multi-racial, multicultural areas in Britain, where black lawyers, waiters, students, dancers, seamen, doctors and actors rubbed shoulders with cockney market traders, jazz fans in from the suburbs, pimps, prostitutes, debutantes and landed gentry.

Trinidadian singer Sam Manning arrived in London in 1934 as calypso’s first international star. His influence was much more than strictly musical. Manning had spent the 1920s in New York, recording his trademark jazz/calypso hybrids and featuring alongside Fats Waller in the original performances of the jazz musical Brown Sugar. That was where he met his partner, the show’s producer Amy Ashwood Garvey, who had formerly been married to Marcus Garvey. The couple founded the Florence Mills Social Club, a jazz nightclub and restaurant in Carnaby Street. Named after the legendary black American cabaret star, it became a gathering place for London’s Caribbean and African intellectuals, and students of the growing Pan-Africanism movement.

Given Sam Manning’s prominence as a singer, he’s often, understandably, credited with introducing calypso to London. Both in Trinidad, however, and when it first reached Britain, calypso was regarded as being as much about the playing as the singing. Indeed, the very first example of recorded calypso has no vocals: in New York in 1912, Lovey’s String Band, a ten-piece Trinidadian fiddle, guitar, banjo and upright bass outfit, cut a danceable instrumental called “Mango Vert”, which was taken to be a different style of jazz. By the time the music crossed the Atlantic in the 1930s, calypso was mingling with Latin and big-band swing as an integral part of dance-orchestra repertoires all across the West Indies, with singers seen as more or less optional extras.

Things were much the same in the UK, where players integrated quickly and relatively painlessly into the established ballroom scene. Two main factors were at work. Calypso being a deceptively complex music to play well, the musicians were of a very high calibre. In addition, dance orchestras were smoothing themselves out closer to Glenn Miller than Count Basie, with barely enough South American flourishes to justify the maracas, so this injection of Caribbean flavour spiced things up in an easy-to-follow, appropriately exotic way.

Meanwhile, London’s serious jazz clubs too were taking on Caribbean influences. With one branch of jazz busily repositioning itself from swing to bebop – complete with asymmetric phrasing, walking basslines and pork pie hats – the music’s broader fanbase welcomed the coming of calypso, thanks to the influx of Trinidadian players, as a blessing. As played by the new wave of jazzmen, calypso’s far more straightforward rhythms helped to keep bebop’s feet on the ground, while still having enough to keep things exciting.

Trinidadians Lauderic Caton and Cyril Blake, respectively a guitarist and a trumpeter, were particularly significant in both these worlds. Caton, an electronics enthusiast, built some of the first electric guitars seen in London, and is credited with introducing the instrument to British jazz, while Blake had been a member of the Southern Syncopated Orchestra. Together they formed the backbone of the house band at Jig’s Club in St Anne’s Court, between Wardour Street and Dean Street. As Cyril Blake and his Jig’s Club Band, their artful calypso-infused jazz turned Jig’s into one of London’s hottest clubs. Despite its insalubrious reputation, it wasn’t unheard of to come across the elegant likes of Fats Waller and Duke Ellington, each of whom employed Caton at some point, down at Jig’s. The pair also played alongside the likes of Coleridge Goode and Dick Katz, and in the dance bands of Bertie King, Ray Ellington and Leslie Thompson, and the ever-popular West Indian All-Stars.

Away from the mainstream, in the black dancehall world of the late 1930s, these various trends came together as hot jazz, which absorbed Latin and swing to osmose into jump jive and that newfangled rhythm & blues, all served with a generous side order of musical calypso. On this scene, the bebop revolution was far less evident – the emphasis at this point was on dancing and straightforward entertainment.

In the upmarket venue, the Paramount Ballroom, the crowd was ordinary working black London, supplemented by visiting servicemen (West Indian and American), merchant seamen on leave, a smattering of African students and musicians looking to hang out. Apart from a scattering of English women, there were virtually no white people; this ballroom scene didn’t draw the bohemian or slumming aristos found in the Soho or Notting Hill clubs, where interracial fraternisation seemed to be the latest rage.

The Paramount was much more straightforward: everyday black folks who had probably had enough of white people for that week, and wanted nothing more on Friday or Saturday night than to relax with people who looked like them. White women could get away with it, even if they risked the wrath of the disproportionately few black women there, but these dancehall crowds were liable to be openly hostile to unfamiliar white men.

With its entertainment policy, too, following West Indian rather than West End traditions, the Paramount became a totally swinging place to be. Like working people everywhere, the audience wanted a wild night out – but it had to be worth the price of admission. The Paramount’s owner, himself a Jamaican immigrant, understood that if his clientele had paid two shillings to get in, he’d better give them a half-a-crown show, and recreated the excitement of dancehalls back home with a dash of London luxury. The musicians reciprocated, too. The stage at the Paramount gained a reputation as somewhere they could really cut loose, in front of a noisily appreciative crowd – something that often came as a relief after ‘day jobs’ in more sedate mainstream situations. While the Paramount never enjoyed the profile of some of the later, more cerebral Soho clubs – because this was jazz for dancing – it was always a fertile arena for exchanging ideas. With big-name visiting players frequently turning up after hours, it hosted all manner of sitting in, showing off and experimentation.

Situations like that, all over London – albeit smaller – served to keep many of the West Indian players below the radar. Working in the ‘corn-fed’ dance bands, they were never considered jazz enough, while by doing their serious playing at less glamorous venues they missed out on the attention they might have otherwise have attracted.

Because it was both big, and open until five or six in the morning, the Paramount was ideal for the many men who had jobs but nowhere to live – ‘No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs’ – and could be arrested for vagrancy if caught dossing on a park bench or in a doorway. With staff turning a sympathetic blind eye, they could snatch some shut-eye on a banquette, then have a wash in the gents.

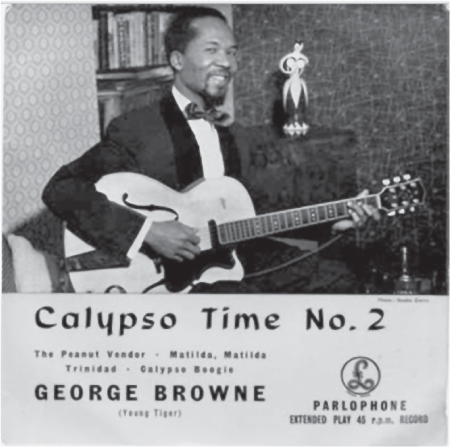

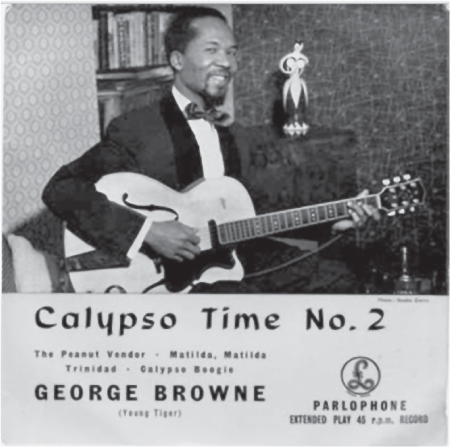

Calypso singers were always part of this London scene, especially in the ballrooms. The first to make a real mark were George Browne and Edric Connor, who arrived from Trinidad as early as 1943 and 1944, respectively. Browne was a bass player who regularly gigged with Caton. During his first year in London, he had a huge hit with the tropically festive number “Christmas Calypso”. As calypso grew ever more popular, he turned to singing full time, and changed his name to Young Tiger.

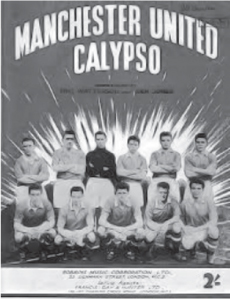

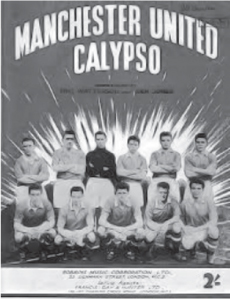

Connor, a singer, actor and music-business mover and shaker, brought over the first Trinidadian steel band to play in Britain in 1951; set up London’s first black talent agency in 1956; was the first black actor to perform with the Royal Shakespeare Company, in 1958; founded the Negro Theatre Workshop, one of Britain’s first all-black drama groups, in 1963; appeared in numerous films and TV dramas; and still found time to cut several albums. His discography includes one of the first-ever official football records, 1956’s “Manchester United Calypso”:

‘… Manchester, Manchester United

A bunch of bouncing Busby Babes

They deserve to be knighted …’

In recent seasons, Connor’s original recording has been spun before home games at Old Trafford, and taken up by the crowd as a chant.

‘CALYPSO’ COMES FROM THE WORD ‘KAISO’, an exclamation of encouragement in the Hausa language, widely spoken in West Africa. Pronounced kye-ee-soh, it meant ‘Go on! Continue!’ Plantation slaves, who were forbidden to speak to each other in the fields and thus communicated by singing, would shout it to each other as mutual support. The rhythms of many African songs are comparable with basic calypso, and were homogenised into a single form in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, adopting a few Europeanisms and instruments along the way. Jamaican mento, which retains the most original instrumentation, remains the closest to what originally came over. Kaiso-based music was prevalent throughout the West Indies, but became known as calypso in Trinidad because, so legend has it, Europeans on that island wouldn’t make the effort to pronounce the word properly.

Developing a strong narrative bent among the slaves, who used it to mock slave masters, comment on everyday life, tell tall tales and have some bawdy fun, kaiso evolved into the combination of satire, protest, innuendo, social commentary and observational comedy we know today. The sharpest calypsonians were contemporary griots, as influential as they were informative. Champions of the underclass, they frequently took the colonial government to task, and criticised the social invasion that accompanied the setting up of American bases on Trinidad during the war. Inevitably the authorities responded: songs were banned, and singers prevented from performing. Despite being exclusively based in New York, the calypso recording industry found itself officially censored – producers at the American record companies had to submit their recordings of Trinidadian singers to British government officials on the island who would – or, as was mostly the case, would not – sanction their release. Contentious titles included “The Censoring Of Calypso Makes Us Glad” – a hilarious piece of sarcasm by Lord Executor that was, of course, banned. In the face of such harassment, many singers opted for life in the UK.

BY THE TIME THE WINDRUSH DOCKED, calypso was popular enough in London to offer all sorts of opportunities. For Kitch and Beginner, it was more a case of how soon would a gig find them than how soon would they find a gig. They were celebrated artists all over the Caribbean, who were happy to front an orchestra playing big-band arrangements, but could also hold their own interacting with boisterous audiences in small clubs, backed by local players, or accompany themselves on guitar on a variety bill in music halls or between orchestra sets in a ballroom. It was not unusual for a star of Kitch’s calibre to dash around the West End playing sets in three or four clubs in a signle night.

One much-told story tells that, days after landing in England and in search of a gig, Kitch began to perform solo in a London pub, where the customers were so outraged that their noisy protests almost reduced him to tears. Supposedly, the disgruntled drinkers’ problem lay in the fact that they ‘couldn’t understand a fucking word’ of the songs. The story continues that Kitch had to risk similar humiliation in several other pubs before anybody would take any notice. While this may or may not be an urban myth, it sounds highly unlikely. Kitch arrived as a big star and didn’t need to scratch around looking for work; it’s unlikely any pub landlord without a reasonably sized West Indian clientele would have let him through the door, let alone put him on stage; and what makes a good calypsonian great is his diction and very correct use of English.

The real problem with this tale is that it crops up time and time again, and is taken to represent the truth. As such it has come to define the relationship between London and the Windrush generation of West Indian arrivals. It depicts Lord Kitchener as some exotic alien, plaintively trying to impress a host who was going to bully him for a while before reluctantly accepting that he might have something of some small value. It epitomises the idea that West Indian immigrants were in London under sufferance, had precious little sense of self worth, and existed only in relation to white English people. That might explain why it gets repeated so often, yet questioned so rarely.

The reality was that, to a large degree, Londoners didn’t know what to expect from the new arrivals or what to do with them. West Indians who endured that period speak of attitudes that varied between openly welcome, outright hostile and completely indifferent in pretty much equal measure. In the years during and immediately after the war, native Londoners made very little attempt to engage with the new arrivals. That wasn’t simply a matter of racism, although there was no shortage of that. It was more the case that the city, being naturally insular, was still recovering from the Luftwaffe onslaught and the wider implications of being at war. West Indians contributed to this lack of engagement, too. Few believed that they needed to instigate any kind of relationship with the host country, as they didn’t think they’d be here very long – maybe five years, certainly no more than ten. The worker recruitment drives across the Caribbean – London Transport in Barbados, British Rail in Jamaica, and the newly formed NHS everywhere – sold the adventure on the notion of rebuilding the Mother Country after the war, and then, job done, going home with pockets bulging with cash. Although it was rare for anybody to go home quickly, the dream was so cherished that among this generation the notion of a black British identity didn’t even begin to form. Their emotions buoyed by the Independence Fever that washed through the Caribbean from the late 1950s onwards, Jamaicans saw themselves as Jamaicans, Kitticians as Kitticians, and so forth. That said, it’s important to remember that while such nationalism promoted a certain amount of inter-island antagonism, and different nationalities tended to live and primarily socialise among their fellow countrymen, everyone was aware that they all had much more in common than they did keeping them apart. After all, it wasn’t as though most Londoners cared whether you were a Grenadian, a St Lucian or a Dominican; generally all that registered was a black face and an unfamiliar accent.

Lord Kitchener, seen here with a double bass, was an accomplished musician as well as a singer.

In such an environment, calypso was massively important to the new arrivals, who felt an understandable sense of disconnect with the West Indies they’d left behind. Hearing a new song was like getting a letter from home. It didn’t even matter that ‘home’ would always be Trinidad, the fact that it was Caribbean tended to override inter-island rivalries. Calypso’s traditions of wordplay and story-telling were embedded all over the West Indies, so a house party that spun calypso records, or a pub featuring a lyrically clever singer, would put you back in touch with who you were.

Almost exclusively experienced live – what records were available were imported from Trinidad, which had an established music industry – calypso functioned much like kaiso, secretly mocking those in power. The sharper wordsmiths would comment on London life and London people with in-jokes and slang that kept things pretty much closed off from anyone apart from themselves and their own crowds. The music owed its popularity to more than just its amusement value; it played a vital role in retaining a keen sense of self in difficult times. Immigrants performing for immigrants, the original London calypso singers would appear as support acts in venues like the Paramount, while also headlining in smaller West Indian clubs and turning up during popular Friday night and Sunday lunchtime sessions in such pubs as the Queens in Brixton or the Colherne in Earls Court. While every bit as exciting and ad hoc as you might find in Port of Spain, however, this was pretty much the original Caribbean form frozen in aspic with very little evolution. Ironically, that lack of reinvention became increasingly significant, as more and more West Indians came to accept that they weren’t going home for anything longer than a visit, and such snapshots from the islands meant so much more.

AS THE 1950s ROLLED AROUND, the big-time London music business began to take calypso seriously. Recording calypso in London was nothing particularly new; as far back as the 1930s, Decca and Regal Zonophone had cut sides by the likes of Sam Manning, Lionel Belasco and Rudolph Dunbar. These were for export only, however, and treated as novelties by the domestic operations. From 1935 onwards, Decca UK tried to release calypso recorded in New York by its American division, but even stars like Attila the Hun, Roaring Lion and Growling Tiger failed to ignite sales. Releases were discontinued in 1937, and all titles deleted in 1940.

By the time the Windrush arrived, most calypso recording was happening on a below-the-radar scene, which put Kitch and Beginner in the studio almost as soon as they arrived. Both cut tunes for London’s most successful calypso label, Hummingbird Records, run by expat Trinidadian businessman Renco Simmons (Trinidad is also known as ‘the Land of the Hummingbird’). Simmons would hire RG Jones’ studio in south London and record well-known calypsonians who were either living in London or passing through. He’d then get records pressed in London primarily for export to Trinidad, with supplementary sales in the capital. Back home, he retailed his records through Hylton Rhyner’s, a chain of tailor’s shops that also sold calypso records (there’s still a Rhyner’s Records in Port of Spain). In London he’d place them in the network of black-owned grocers, cafes and barbers, which had been beyond Decca’s distribution arm.

While this enhanced reputations in Trinidad, and catered to West Indian London, it had no wider impact. That all changed when Denis Preston, a suave, charismatic hipster who had been on the London jazz scene since the early 1940s, discovered calypso. Preston, who briefly dubbed himself Saint Denis, was a contributor to Jazz Music magazine and an announcer on the BBC’s Radio Rhythm Club. He was also a groundbreaking independent music producer and a savvy record businessman. It was Preston who pioneered the model of recording artists at his own expense and then leasing the results to record companies. He also hired the fledgling Joe Meek as his engineer, and built Lansdowne Studios in Ladbroke Grove in 1957.

Preston happened on calypso in 1946, when, as jazz editor of Musical Express – today’s NME, just after it dropped the words ‘Accordion Times &’ and before it added ‘New’ – he was promoting a ragtime concert in London at which Freddie Grant & His West Indian Calypsonians were halfway down the bill. Three years later, when working for Decca in New York, he came across the music again as a favourite of the dance bands in Harlem clubs. Seriously impressed, he convinced EMI’s Parlophone Records on his return to Blighty to get into the calypso business, and took Kitch and Beginner into the company’s prestigious Abbey Road studios early in 1950.

As an independent recording supervisor – the term ‘producer’ was not yet in use – Preston was not obliged to use the in-house musicians, so he backed each singer with a Cyril Blake group. Astute enough to realise that these artists understood the genre better than he did, and enough of a jazz fan to respect musicianship, he simply let them get on with it, and sat back digging the crazy sounds. Preston’s calypso sessions during the next few years faithfully reproduced the sounds of the capital’s nightclubs and black ballrooms – big- and small-band arrangements; usually percussion-heavy and Latin-jazz-based; mostly liltingly sophisticated, sometimes disarmingly rustic, yet always beautifully sung. His intelligent and deferential approach succeeded on several levels.

Requirements in the Caribbean were little different from those of expats in London, so these high-quality recordings – featuring stars like Bill Rogers and Roaring Lion as well as Kitch and Beginner, often performing songs that had been previously recorded elsewhere, and spared modification by mainstream record companies, went down very well in the West Indies. The subject matter, too, remained traditional with such bawdy lyrics as Roaring Lion’s “Ugly Woman”:

‘If you want to be happy and live a king’s life

Never make a pretty woman your wife …

From a logical point of view

Always have a woman uglier than you …’ or “Tick! Tick! (The Story of the Lost Watch)” – a hilariously ludicrous story of a woman who steals a watch and hides it in her vagina:

‘What a confusion

A fellow lost his watch in the railway station

A girl named Imelda was suspected of being the burglar

She had no purse, no pockets in her clothes

Where she had this watch hidden, goodness knows …’

While satisfying EMI’s primary objective, to compete with US companies selling calypso records in the Caribbean, these recordings simultaneously had the edge over the imports in the London market, as the singers referenced their new home. On “The Underground Train”, Lord Kitchener sang of the perils of getting distracted on the Tube:

‘Never me again, to get back on the underground train

I jump in the train, sit down on a seat relaxing mi brain

I started to admire a young lady’s face

Through the admiration I passed the place

To tell you the truth I was in a mush

When I find myself at Shepherds Bush …’

Meanwhile Beginner’s commentary on the 1950 election result, “General Election”, came complete with a stylistic explanation as an introduction:

‘Me, Lord Beginner, make this calypso in the style of the old minor calypso which we sing in Trinidad since many years.’

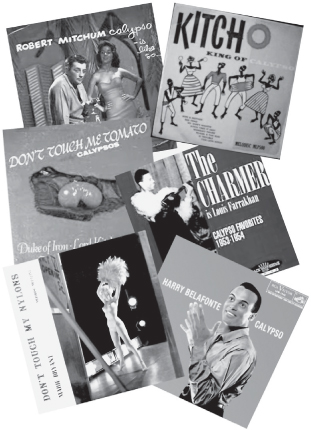

At much the same time, EMI chanced upon another lucrative sales opportunity for calypso: the UK mainstream pop market. An audience with no previous interest in calypso – Johnnie Ray, Tony Bennett or Rosemary Clooney was where it was at – had been introduced to it by the dance orchestras, and was now buying it on EMI’s readily accessible gramophone records. Other British record companies raced to add calypso to their release schedules. Not the London version, though, or even the original imported direct from Trinidad; the major labels opted for American calypso, made in America by Americans.

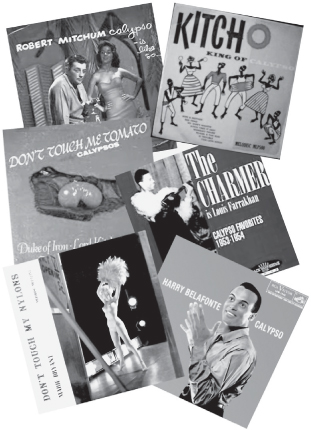

ASTONISHING AS IT MAY SOUND, calypso – or at least, a strictly white-bread version thereof – was a major force in US popular music of the 1950s. As a mainstream-friendly fad, calypso had been kicked off when Trinidad-stationed US servicemen brought it home after the war. The biggest US pop hit of 1945, the Andrews Sisters’ “Rum & Coca-Cola”, was a plagiarised version of a Trinidadian hit by Lord Invader and Lionel Belasco, from two years earlier. Despite being banned by some radio networks – because it mentioned an alcoholic beverage, not because it’s actually a song about prostitution – the record sold 2.5 million copies.

In the US, as in the UK, calypso rhythms were taken up by orchestras in ballrooms and on the radio, as part of the trend for South American experimentation. Things consolidated in 1947, when the calypso-powered, big-budget musical Caribbean Carnival became a long-running Broadway success. Into the 1950s, and boosted by the emerging American/Caribbean tourist industry, calypso became a big part of US pop music. Amid widespread disapproval of the new ‘degenerate’ teenage soundtrack of rock’n’roll, many in the music industry wishfully imagined that calypso might prove a serious rival.

Dozens of calypso records came out in the US during the first half of the decade. High-profile artists – black and white alike, and including Rosemary Clooney, Louis Jordan and Ella Fitzgerald – covered Trinidadian favourites. Nightclubs opted for tropical decor and names like the Calypso Hut or the Island Rooms, while all manner of crooners invested in flowered shirts and frayed straw hats. TV variety shows incorporated calypso-themed numbers as a matter of course, while sitcoms wrote bursts of calypso into scripts. Hollywood too got in on the act, creating low-budget, teen-oriented movies like Bop Girl Goes Calypso, Calypso Joe (starring a young Angie Dickinson) and Calypso Heatwave. The latter featured Maya Angelou – yes, that Maya Angelou – who, prior to her literary calling and social activism, had a career as a calypso singer and dancer. Indeed, she took her stage name because Marguerite Johnson was deemed insufficiently exotic.

Another improbable pop-calypsonian was the man who would later be addressed as Louis Farrakhan, National Representative of the Nation of Islam. Back in the 1950s, while still Louis Eugene Walcott, the Brooklyn-born former child-prodigy violinist turned his musical talent to singing, and recorded six well-received calypso albums under the soubriquet The Charmer. He was no stranger to controversy then, either. His 1953 hit “Is She Is Or Is She Ain’t?” – also released in the UK – told of George Jorgensen Jr, the first sex-change celebrity, who hit the US talk-show circuit after having the surgery in Denmark:

‘With this modern surgery

They changed him from a he to a she

But behind that lipstick, rouge and paint

I got to know is she is or is she ain’t? …’

Almost as remarkable was screen tough-guy Robert Mitchum’s 1957 album Calypso – Is Like So. It’s not noteworthy simply because he made it – everybody was making calypso albums by then – but because Mitchum, an accomplished singer and songwriter, insisted on making genuine, as opposed to watered-down, calypso. He recorded the album in Tobago, where he had discovered the music while filming 1957’s Fire Down Below, co-starring Edric Connor. Mitchum used local musicians, and studied the island’s inflections and colloquialisms to incorporate them into his vocals. Although his album didn’t sell nearly as well as Jamaican American Harry Belafonte’s 1956 Calypso, it remains one of the few US offerings that Caribbean calypsonians respect. Belafonte’s album, incidentally, which included “The Banana Boat Song (Day-O)”, was the world’s first-ever million-selling LP, and represented the peak of American calypso. Hardly surprisingly it began to wane when, later that year, a 21-year-old Elvis Presley appeared on the Milton Berle Show in front of forty million viewers. Suddenly, lilting Caribbean rhythms were no longer quite cutting it with the kids.

During calypso’s American ascendancy, US companies shipped records in large quantities to their UK labels. In 1957, for example, “The Banana Boat Song” was a UK hit for three different acts – Harry Belafonte, Shirley Bassey, and future actor Alan Arkin’s pop/folk group, the Tarriers. Although British audiences had previously seemed to prefer their calypso with an earthier tone, British record companies were dazzled into believing that the US music business was showing how things should be done. However, spectacularly missing the point of calypso, they pulled out as soon as sales palled – if these glamorous Americans couldn’t find traction, how could a bunch of unknown West Indians?

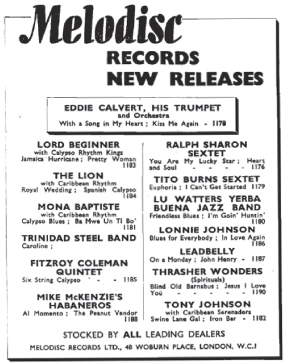

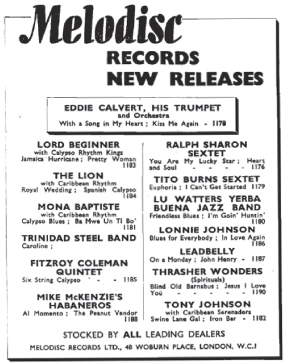

Even EMI came to think their calypsonians would never pay back any more than their export sales, so it fell to London’s thriving independent record labels to take up where they let off. Emil Shallit, an immigrant of indeterminate Eastern European origin, seized this moment to move to the forefront of the calypso market.

A CHARACTER SO COLOURFUL he deserves his own paintbox, Shallit had arrived in London just after the war. He claimed to have been an Allied spy, and that the startup capital with which he founded Melodisc Records in 1947 was a pay-off for his clandestine services. He had originally based his office in the US, licensing American jazz and blues for British release. That allowed him to do what he did best – schmooze New York hipsters. After falling out with his business partner, he decamped to London where he looked to record rather than simply licence in. The music he knew most about was black music.

Sure of his ability to go anywhere and get on with anybody – apparently, that’s what made him such a good spy – Shallit moved among the subcultures of London, and seemed innately to understand what they wanted. Time and time again, his small company was agile enough to shift from style to style on no more than his say-so. Not tied in to any particular distribution channel, he could put Melodisc records anywhere he thought they’d sell. If that meant using a cosmetics wholesaler to put the records in hairdressing salons, or a food importer to get them into African-owned grocery stores, he didn’t need a series of management meetings and a risk-assessment strategy. During the 1950s, Emil Shallit built Melodisc into one of the largest independent labels in London, while himself becoming a radical and important figure in the development of British black music.

Shallit was aware how important it was for music to be genuinely of a genre, while shrewd enough to realise that any transplanted music also needed to represent its new home. He understood that the core market had new influences and experiences to reflect, and, vitally, that any cultural crossover to a larger audience could only happen if it acknowledged those surroundings. During the 1950s, Melodisc was the first label to record West African Londoners playing highlife with contributions by West Indians. It also brought in Jamaican artists like Miss Lou to cut mento in London, backed by Jamaican players who’d been steeped in the capital’s music scene for years, and was one of the first labels to recognise the value of Caribbean jazz, promoting the likes of Joe Harriott and Russell Henderson to be bandleaders.

The backbone of the Melodisc catalogue, however, was calypso. Shallit had employed Denis Preston to produce some of Melodisc’s earliest releases at the start of the 1950s, but he proved to be more of a facilitator than proactively creative. Seeking to move the music forward, Shallit soon replaced him with Rupert Nurse, a Port-of-Spain-born multi-instrumentalist and childhood friend of Lord Kitchener, who became Melodisc’s musical director, A&R man and in-house producer. Shallit knew Nurse from the clubs, where he had played jazz, calypso and swing since arriving in the UK in 1945.

As a working musician and orchestrator, Nurse had the theoretic and practical understanding to feel confident about taking chances. Long determined to modernise calypso by applying big-band jazz and swing arrangements to a traditional framework, he’d left Trinidad after incurring the displeasure of the local musical establishment for doing exactly that. It was thanks to this musician-friendly approach, on the other hand, that Melodisc had no problem hoovering up Parlophone’s calypso roster when that company abandoned the genre towards the end of the 1950s.

Melodisc sessions took place in Esquire Records’ makeshift studio, in the basement of Bedford Court Mansions in Covent Garden. Nurse used a core of Trinidadian and Guyanese musicians – saxophonist Al Timothy was the effective bandleader, with pianist Russ Henderson, guitarist Fitzroy Coleman, trumpeter Rannie Hart and clarinettist Freddie Grant as regulars. He then brought in players like Joe Harriott, Latin-style trumpeter Peter Joachim and John Maynard on trombone to make up a bigger band sound – essentially the same unit that backed Kitch and the other singers on their bigger club dates. Nurse also introduced the steel pan into the recording sessions. That was an unusual move, as despite the instrument’s Trinidadian roots it was seldom used in calypso backing bands. Nurse simply loved its sound, and felt that its semitone capabilities added an extra harmonic layer within his jazz arrangements, giving the music instant appeal.

As Nurse’s method was entirely opposite to the standard ballroom method of sprinkling calypso-ish rhythms and accents atop standard dance-orchestra arrangements, his results were always going to be genuinely calypso. He also wrote out formal charts rather than depending on improvised arrangements. Far from restricting the players, this gave them more freedom, as it built a reliable framework within which they could operate. Suddenly, a new level of sophistication gave the melodies a whole extra dimension and depth of structure. While the rhythm section drove the momentum, supplemented with brass riffs, the melodies were so securely anchored that players could weave their own patterns. Innovative yet still making complete sense, the new approach brought calypso up to date, and made it a much more powerful means of communication. It also allowed continuity within a band if the musicians changed.

The bebop sensibilities that were always around dovetailed perfectly, giving things a London jazz flavour, and Nurse’s innate sense of swing kept the music easily accessible. Top singers like Kitch or Roaring Lion could now sing with all their energy, instead of the semi-crooning style that better suited ballroom calypso. In giving the singers free rein, Nurse knew that they would carry the calypso swing, and leave the band free to play jazz. Obvious examples of this include “Calypso Be” by Young Tiger, which ironically decries bebop and beboppers against a background that embraces it:

‘This modern music got me confuse

Tell you, friends, I’m quite unenthused

I like Pee Wee Hunt and the great Count Basie

But can’t make head nor tail of this Dizzy Gillespie …’

Similarly, Kitch’s “Bebop Calypso”, which eulogises bebop with list of recommended artists and records. A talented melody writer, Kitch loved working with his old friend Nurse. He’d sing his calypso tunes to the musician, sometimes down the phone, and the arranger would write them down and come up with the orchestration.

THE MELODISC STYLE BROUGHT CALYPSO right into the modern era, giving it an edge that impressed jazz fans while making the Caribbean music sound familiar enough for broad appeal. Musicians loved it because it gave them a chance to show off on record as well as on the bandstand. One of those players was Russ Henderson, a jazz pianist and steel-pan player who came to London from Trinidad to study piano tuning in 1951, but quickly opted for life as a full-time musician. Still active and perpetually cheerful at 87, Russ remembers backing jazz players, highlife musicians and calypsonians at Melodisc, as well recording there under his own name. He still marvels at how those sessions turned out:

‘Although there was a good live music scene in London back then, there wasn’t much recording. At the time Melodisc was really the main company doing West Indian recording, and they recorded African highlife as well, like Ambrose Campbell, so there was always a lot of African influence. They recorded jazz, too. But this was very good, it was like a big melting pot in there. Rupert Nurse had his key players – I was one of them – who were Trinidadian and West Indian musicians, mostly from a jazz background, but knew all about calypso. Then there would be other players who might be West Indian or might be African, or even English like Cab Kaye [Finley Quaye’s father, a singer and pianist born in London to a Ghanaian father and English mother in 1922]. Because we all played in the clubs together, you know how musicians are, they say to each other “Can you play this gig?” or “Can you play that gig?” So if Rupert Nurse would say he needed a trumpeter for tomorrow, you’d see somebody that evening in a club that you’d bring with you. We didn’t care where we was actually from, because we were all of us black in London.

‘It was important for the music, because at Melodisc it had a feel it didn’t get anywhere else. There was jazz and calypso mixed elsewhere, but this was calypso but played with a real jazz swing, we could solo … everything … and some of these guys were the best jazzmen in London. Also, what made it so much like jazz was that we all brought bits of our own musical backgrounds and musical tastes to the studio, and everything counted, because Rupert Nurse could organise it. We [the musicians] all understood what he was doing because that was the kind of thing we’d been trying, so it was a joint effort really. He wrote the charts, but it was down to us to interpret them in our playing.

‘It was very good for us as people too, because it brought different people together. Before I came to England I hadn’t a personal African friend. We knew of a few Africans, and we could say, “Oh he’s from Ghana”. But once I came here, I went on tour with African drummers when I travelled in 1952 to Belgium, and I recorded with Jamaicans … everybody. When you got over here, there would be the question of, “Where are you from?”, but it didn’t matter, you were Caribbean! Or you were African! We all became friends and we all learned a lot from each other – not just music, but about life. As a Trinidadian, I used to think that coming into contact with other people like that was the greatest thing that happened in my life. Making us get to know the other islands, because when I was at home you didn’t really get to know anybody else from elsewhere.

‘Really it wasn’t just for us musicians that happened, it was happening in life too. So many of the people that came to England at that time were getting to know people that they would never have met if they’d stayed at home [in the West Indies]. People socialised and worked together, and realised how they had to support each other. That everybody had something to offer the others.’

THE CROSSOVER WAS COMMERCIALLY useful too. With a great deal of to-ing and fro-ing between London and Nigeria, Ghana and Sierra Leone by musicians for studio and live work, the London recordings had a considerable influence on the development of local high-life music. West Africa, and Ghana (then the Gold Coast) in particular, had been a huge market for Parlophone’s calypso, and Melodisc followed suit. Such Lord Beginner tunes as “Gold Coast Victory” and “Gold Coast Champion” went down a storm, and he toured the region extensively. The biggest London hits were Kitch’s “Birth Of Ghana”, celebrating the new nation’s 1956 independence, and Young Tiger’s “Freedom For Ghana”; twenty thousand copies of each were exported to Africa. Young Tiger was such a star in Nigeria that when the country became independent from Britain in 1960, its new government asked him to write a national anthem – he declined. The other Caribbean islands were not forgotten either. Both Kitch and Beginner cut Jamaican-friendly songs – “Jamaican Woman”, “Sweet Jamaica” and “Jamaica Hurricane” among them – but the most striking example was Young Tiger’s “Jamaica Farewell”, in which the singer’s broad Trinidadian accent can be heard rueing the day he left his lovely Jamaica.

Russ believes that those calypsos did much to break down barriers between the immigrants and native Londoners:

‘What we were doing at Melodisc helped English people to get to know us a bit more, because they didn’t have a clue about calypso before those records Kitch started making. When we played in the big ballrooms in the West End, most of the time it was rhumbas, sambas and show tunes, because they wanted music for dancing. All they knew about calypso was songs like “Mary Ann” or “Rum & Coca Cola” that was left over from the war. We played calypso at the West Indian ballrooms or the late-night jazz clubs or a place like the Sunset, which was owned by a Jamaican, and used to have a cabaret on.

‘When Rupert Nurse added jazz to the basic calypso, it moved it to where it began to appeal to English people because they knew how to dance to it. Up until then, unless it was some dance band playing Latin or something with a bit of a calypso beat, they didn’t know what to do. After this, they figured out how to dance to it. Which was the best thing that could have happened, because it introduced the Caribbean culture to the English.’

There was no record-label exclusivity within the capital’s calypso community; under various, often hastily conceived group names, the same players would crop up recording for anyone who would pay them. For example, the singer Marie Bryant recorded the same song, “Tomato”, for two labels using pretty much the same backing band. This led to something of a boom in London calypso recording; although Melodisc dominated the market, they didn’t have it all to themselves.

With London recordings as well as tracks licensed in from the US, Decca had a considerable roster. So too did Lyragon, an independent founded by Jack Chilkes, Emil Shallit’s original partner in Melodisc. Pye Nixa built up a sizeable made-in-London catalogue, while the jazz label Savoy imported tunes it had already put out in America. Even Parlophone dipped a toe back in the waters, but with strictly comedy, pop chart-chasing fare, as they revived the comedy line they’d started in the 1950s with Peter Sellers’ “Dipso Calypso” (1955) and Ivor & Basil Kirchin Band’s “Calypso!!” (1957) – so shouty and boisterous a dance track that it needed two exclamation marks – with Bernard Cribbins’ “Gossip Calypso” (1962).

ONE OF THE MOST SIGNIFICANT developments as the music migrated from Parlophone to Melodisc was a shift in lyrical approach. While Parlophone’s output had been witty, articulate, verbally dexterous and undoubtedly of Caribbean descent, the songs tended to come at things from as all-embracing a perspective as possible. Thus Lord Beginner’s “Housewives” focussed on the problems of rationing and stretching a housekeeping budget; Kitch’s “My Landlady” bemoaned interfering proprietors; Young Tiger’s “I Was There (At The Coronation)” rhapsodised Queen Elizabeth’s Coronation parade:

‘Her Majesty looked really divine

In her crimson robe trimmed with ermine …’

Now, however, independents like Melodisc and Lyragon, which saw themselves as catering to the core audience, felt less constrained. Increasingly, therefore, the next wave of calypsos supplemented the sophisticated arrangements with more raucous and colloquial vocals. And, of course, the bawdiness factor was ratcheted up.

As the origins of calypso singing – chatting about the slave master in a way that he couldn’t understand – had required so much to be said without actually saying it, innuendo was something of an art form. Caribbean dancehall crowds loved a lewd lyric. Melodisc put out such risqué gems as “My Wife’s Nightie”, “Short Skirts” and “The Big Instrument”, but pride of place went to Kitch’s double entendre-laden “Saxophone Number 2”:

‘From the time the woman wake

She wouldn’t leave me sax for heaven’s sake

She say she like to play the tune

That remind her of the honeymoon …’

If you wanted innuendo, calypso was always happy to give you one. Singer, jazz dancer and all-round sex bomb Marie Bryant’s recording of “Don’t Touch Me Nylon” was so suggestive it prompted questions in Parliament. Meantime, her record company put a stripper on the sleeve.

While this kind of ‘Ooh err, Missus!’ humour might seem somewhat puerile from a twenty-first-century perspective, in London in 1956, two years before the first Carry On … film, it caused quite a stir. The BBC was moved to sticker a selection of discs in their library with the stark warning ‘Do not play this record!’, while Marie Bryant’s 1954 Melodisc hit “Don’t Touch Me Nylon” – a song about statically charged underwear – prompted questions in the House. Brixton’s Labour MP Lt Colonel Marcus Lipton, was so enraged that he stood up and spluttered about ‘gramophone records of an indecent character’, saying that it couldn’t possibly be ‘in the public interest that the wretched things should continue to be publicly sold.’

Incidentally, Marie Bryant was one of Melodisc’s more interesting London-based recording artists. Born in Meridian, Mississippi, in 1919, she was dancing with Louis Armstrong’s band at age 15, had a residency at the Cotton Club, toured with Duke Ellington’s orchestra for three years. and worked in films and stage shows. By the time she moved to London in the early 1950s, she had become a black superstar and one of the world’s most sought-after jazz and exotic dancers – her YouTube clips are a joy.

ANOTHER ASPECT OF THE GREATER freedom of the independent labels was demonstrated when the cheerful optimism of “London Is The Place For Me” gave way to a starker view. When the police seemed incapable of stopping racist attacks perpetrated by Teddy Boys, Lord Invader’s “Teddy Boy Calypso (Cat-O-Nine)” proposed a straightforward solution. Kitch summed up how many new arrivals felt about their treatment in the capital in “If You’re Brown”:

‘It’s a shame it’s unfair but what can you do

The colour of your skin makes it hard for you…

If you’re brown they say you can stick around

If you’re white well everything’s all right

If your skin is dark, no use, you try

You got to suffer until you die …’

He also issued a clear warning to fellow immigrants that, in London, there was none of the shadism that might have made life easier for light-skinned black people back home:

‘If you think that the complexion of your face

Can hide you from the negro race

No! You can never get away from the fact

If you not white you considered black …’

Later, on an album entitled Curfew Time, he would include the track “Black Power”.

Not surprisingly, with nosey landladies, troublesome mothers-in-law and bedroom transgressions being the same for everyone, the saucier strand of London calypsos captured a sizeable domestic audience. Such innuendo-laced numbers were not so different from the lewd music-hall comedy that lived on in theatre variety shows, which indeed often featured calypsonians. Calypso had no less enthusiastic a following among the educated elements of Britain’s post-war generation, determined not to make the mistakes of their parents. Evolving out of London’s jazz-loving, anti-establishment bohemians, and latching on to aspects of America’s folk revivalism, a UK protest movement was gathering momentum. As they preached peace and revolution from coffee bars in Soho, Fitzrovia and Notting Hill, it was an easy leap for them to ally with victims of institutionalised racial prejudice, whose singing mocked the establishment and spoke of how hard life was for black folk in the capital. In addition, the apparent spontaneity of small-scale live performances of a singer, his guitar and a witty narrative-led song precisely fit the folk-music criteria – Soho’s very underground, beat generation Club du Faubourg frequently featured calypso singers.

After the war, this influential boho crowd contributed greatly to the cultural reshaping of Britain. Forerunners of the hippies, they thought internationally, concerned themselves with philosophy as much as action, and were fundamentally anti-racist. They were responsible for CND (the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament), devising the symbol that’s now known as the peace sign (it’s the letters C, N & D in semaphore). On the anti-nuclear Aldermaston marches, from 1958 onwards, it was more or less obligatory to have a pan-round-the-neck steel band. The movement connected with the wave of Caribbean thinkers, writers and trade unionists who settled in London during the 1950s, a disproportionate number of whom were Trinidadian. Cultural heavyweights and social activists such as CLR James, Sam Selvon, Claudia Jones, John La Rose and VS Naipaul all made strong links with London’s modern intellectuals.

West End aristocrats had long since adopted calypso. too. At toney establishments like the Café Royal, the Embassy Club, and the Hurlingham Club in Chelsea, calypso performers became regulars, and they were also in demand for deb balls and Oxbridge bashes. The music had first made its mark on the royal family, with an incident involving the Duke of Edinburgh and Young Tiger at Mayfair’s Orchid Room. When the singer spotted the future Prince Philip, who was engaged to then-Princess Elizabeth, he substituted the lyrics of “Rum & Coca Cola” with some that discussed upcoming nuptials in a less-than-totally-reverent manner. The horrified club manager apologised from the stage and gave Tiger a thorough dressing-down. The next night, however, a much larger royal party turned up, with one request: ‘Sing it again, man!’ This upper-class audience received another fillip in 1955, when Princess Margaret, the Queen’s nightclubbing younger sister, took a Caribbean cruise. With the princess seeking local entertainment at every port of call, the holiday came to be known as her “Calypso Tour”, while the lagoon at Pigeon Point in Tobago was renamed the Nylon Pool after the stockings she removed to dance barefoot on the sand.

Incidentally, the two ends of London’s calypso audience presented something of a sartorial irony. Players at a West Indian club or suburban ballroom wouldn’t have dreamed of taking the stage in anything less than a suit or a dinner jacket – even in the studio, it would be unusual to even loosen the tie. Yet when they played to high society, they were expected to kit themselves out like beachcombers: flowered shirts, cutoff stripey or white trousers, and straw hats that had clearly been chewed by a donkey.

WITH ALL THIS INTELLECTUAL, Oxbridge-educated and patrician support, calypso soon staked a serious claim on the television side of the BBC. There, as the colonies’ most fully formed musical expression, it was a shoe-in when exotic music and dance was called for. Calypso’s earliest regular showing was on the hour-long, Friday-night variety show, Kaleidoscope, transmitted from London’s Alexandra Palace, from 1946 until 1953. Calypsonians would feature amid the antiques experts on Collectors’ Corner, the Amazing Memory Man and the whodunit drama segment. Set against today’s tightly-formatted TV, such a line-up seems astonishing, but in the 1940s and 1950s Britain still had a flourishing music-hall circuit where practically anything went, and on TV, ‘variety’ meant exactly that.

In 1950, Trinidadian dancer and choreographer Boscoe Holder had his calypso music and dance extravaganza, Bal Creole, screened not once but twice, in June and August. All TV was live back then, so it couldn’t be repeated, and was performed again. Similarly, the Caribbean Cabaret series featured Holder and his wife Sheila Clarke; lords Kitchener and Beginner; Edric Connor; steel bands; and all manner of London’s West Indian musicians. There were also specials, loaded with Britain’s black talent, like It’s Fun To Dance, We Got Rhythm and Bongo, in 1951, 1955 and 1958 respectively, the last of which was produced by former Sadler’s Wells ballerina Margaret Dale.

In 1957, the Beeb screened the second series of The Winifred Atwell Show after outbidding ITV who had broadcast the first ten episodes of the variety series. Trinidadian Atwell had arrived in London in 1946 to study classical piano at the Royal Academy of Music, where she became the first woman to gain that establishment’s highest grading. At the same time, she became one of the brightest stars of the capital’s concert hall circuit as she supported herself by playing ragtime jazz and boogie-woogie. Such was the success of what began as a sideline, she became the first black artist to have a number one hit and sell a million records in the UK; and she remains the only female instrumentalist to have topped the UK singles charts (with “Let’s Have A Party” in 1954). Atwell’s playing will be familiar to British snooker fans of a certain age, as it’s her recording of “Black and White Rag” that was the theme tune for BBC TV’s long-running snooker show Pot Black. She made a follow-up series for the BBC, then took the show to Australia where it was broadcast during 1960 and 1961.

Another early instance of the Beeb’s commitment to multiculturalism came when Young Tiger was broadcast singing his celebratory calypso “I Was There (At The Coronation)”, on the very evening of the event. The speed with which the song went on air saw it lauded by the broadcasters as the perfect example of the calypsonian’s art of improvisation. It didn’t seem to occur to anybody that, as with Kitch’s Tilbury performance, the song had been written in advance – three weeks previously, when Tiger read newspaper reports of the coach’s route, and what Her Majesty what be wearing. How else could Parlophone have had copies in the shops the next day?

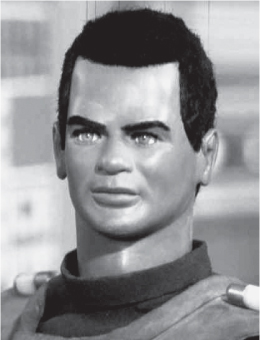

WHEN CALYPSO MADE ITS MOST significant impact in the UK, the man responsible was Cy Grant. He had come to England from British Guyana when he joined the RAF in 1941, and served in a bomber crew during the war. After his plane was shot down, he spent two years in a POW camp, classified by the Nazis as ‘of indeterminate race’. He qualified as a barrister on demob, but found employment opportunities limited in London’s institutionally racist legal system. Driven by a fierce sense of social justice, he took acting and singing lessons, and set out to use the performing arts to promote attitude change.

In the wake of immediate success on the folk-singing circuit and regular acting work on TV and stage, Grant was given a television chat show on ATV in 1956. Hosting For Members Only, he’d intersperse his interviews of newsworthy figures with singing and playing the guitar. Grant’s quick intelligence, drama-school diction and rich baritone got him noticed by Tonight, a daily, early-evening BBC show that covered current affairs in an ultra-relaxed fashion – the first flowerings of television satire. Grant was signed up to sing the day’s news highlights as a calypso composed that afternoon, with lyrics co-written by the incisively witty political journalist Bernard Levin. These clever, cutting, frequently hilarious songs returned calypso to its slave master-mocking kaiso roots, and it became the accepted language of musical satire.

Cy Grant provided the voice for Captain Scarlet’s Lieutenant Green. Yes, Green was black all along.

A huge hit, this was also the first time a black person had appeared regularly on national television (For Members Only was only shown in a couple of ITV regions). Grant stayed for two years, before quitting in case people thought it was all he could do. In the 1960s Grant scored another first for a black actor, as the voice of Lieutenant Green in the puppet drama Captain Scarlet And The Mysterons.

As satire grew better established, and comedy ever more biting, it became almost unthinkable not to include a humorously scathing calypso in the mix. The most vividly remembered example formed part of the BBC’s That Was The Week That Was in 1964, which was groundbreaking in its merciless lampooning of political and establishment figures. No one on the programme cared if technicians or studio equipment came into shot, and as the night’s final broadcast it was open-ended, continuing until the team decided to stop. Keith Waterhouse, John Bird, Peter Cook, Dennis Potter, Bill Oddie, Kenneth Tynan, John Betjeman and several future Pythons were on the TW3 team – and so too was Lance Percival. A middle-class white lad from Kent, Percival had spent the mid-1950s in Canada, where he’d achieved fame singing calypsos as Lord Lance – laid-back calypso-style (flowered shirt and stuff) from the neck down, monocle and top hat above. His actual performance was far more conventional, his singing was top class, and Trinidadian calypsonians still talk with reverence about his lyrical talents. Percival’s role on TW3 was to take suggestions shouted from the audience, usually concerning current events, and make up and sing a calypso.

The segment was a major success, and he continued to supplement his career as a comedy actor by singing calypso in cabaret and on TV. In 1965 he notched up the biggest hit by a British calypsonian, when his version of “Shame And Scandal In The Family” reached number 37 in the charts. When Tonight and TW3 were giving calypso its largest British audience, however, the music had for around half a decade ceased to count as a pop style. That wasn’t anything to do with calypso itself, more the environment in which it found itself. By the end of the 1950s, rock’n’roll had pretty much swept away everything in its path, with the likes of Cliff, Adam Faith and Johnny Kidd leading the homegrown wave. When Lance Percival was doing his thing, the Beatles had released three albums, and the Supremes were spearheading the arrival of Motown on British shores.

Calypso’s new popular context even served to work against it, as the public were seeing the genre purely as comedy, not a pop style to be taken seriously. Anywhere outside the satirical environment, that gave it novelty status, a perception heightened by an obviously Caribbean art being delivered by a pasty white boy. To be fair, though, calypso had done itself no favours, as there had been little musical advancement since Rupert Nurse’s sessions at the start of the 1950s.

WHEN, CRUCIALLY, THE JAMAICAN recording industry got underway at the end of the 1950s, JA boogie (the island’s take on R&B) and ska took over London’s West Indian scene. This happened almost overnight, thanks to the Jamaican-owned sound systems that had previously played American R&B, jazz and calypso, and the large Jamaican audience that was poised, waiting for something of its own to dance to. By now, half of all Caribbean immigrants in London were from Jamaica.

A steady stream of Jamaican recordings was already being informally imported into London when Emil Shallit got involved in 1960. Never slow to spot a developing trend in an ethnic market, he launched the Melodisc subsidiary label Blue Beat, dedicated to Jamaican music. Shallit travelled to the island to make deals with the biggest producers for UK rights to their material. He transferred the resources that would otherwise have gone into calypso into ska instead, and marketed it to exactly the same audience. He also hoovered up many of the same players for his London ska sessions. Suddenly ska became the official soundtrack of black London; and entirely understandably, many Trinidadian calypsonians, Kitch included, went home for good when their island gained its independence in 1962.

EVEN THOUGH IT CEASED TO HAVE MUCH SWAY beyond specialist circles, London calypso did not die out. When soca – a modern, danceable fusion of soul and calypso – emerged during the 1970s, the music got a considerable boost in the capital. The London Calypso Tent at the Notting Hill Carnival, and the junior calypso competitions held during Black History Month, remain lively affairs. The Association of British Calypsonians, formed in 1991, maintains links and exchange programmes with the Caribbean. Calypso in twenty-first-century London has evolved into a far more world-embracing scene, with performers likely to have roots from anywhere in the Caribbean or even Africa, and its subject matter tends to deal with global rather than parochial concerns.

While calypso may not have made as deep an impression as reggae or funk, the very fact that it established itself as part of mainstream British entertainment marked a historic cultural moment. It represented the first time in the United Kingdom that an immigrant group had expressed its relationship with its new home in song, and developed a style that had absorbed that environment. For the first time too, an imported musical style made a significant impact on the domestic music industry. Calypso had not merely existed in immigrant or left-field environments, speaking more about ‘back home’ than ‘new home’. In a two-way process, both host and arrival musical cultures had borrowed from each other with a healthy degree of respect.

A mere fifteen years after the Windrush docked, this truly marked the beginnings of Britain as a culturally multicultural society. It indicated an acceptance for new arrivals on a social level, and a genuine curiosity as to what they had to offer. That didn’t end with calypso. The fact that the more genuine side of the music had shown itself to have domestic appeal set something of a precedent. Ever since then, the British, and Londoners above all, have shown a consistent appetite for imported music, provided it has some meaning and substance.

The success of calypso served as a blueprint for the musical integrations that were to occur over the next fifty or so years. And that in turn says a great deal about attitudes towards ‘newcomers’ in the capital. As one of those two celebrated Windrush passengers predicted in his 1952 recording, “Mix Up Matrimony”:

‘With racial segregation I can see universally

Fading gradually …’