By the time printmaker Azaria Mbatha left the Evangelical Lutheran Art and Craft Centre (which had now moved from Mapumulo to nearby Rorke’s Drift) to return to Sweden in 1969, he had trained fellow artist Namibian John Ndevasia Muafangejo in the technique of linocutting.

Like Mbatha, Muafangejo showed a particular affinity for the linocut process, often incorporating text and thus adding a layer of narrative to his images. His style is quite distinct, with rich and energetically worked detail. With a Muafangejo print, one is always aware of the very human artist behind the image, a factor that has contributed to their immense popularity in South Africa. His subjects were stories from the Bible, current events as reflected in the press, reconstructions of historical events, and commentaries on his own personal experiences.

In An Interview of Cape Town University in 1971 (1971, page 27) Muafangejo portrays a scene from an interview at the University of Cape Town, where he was applying to study art. In the image he is the sole black person in the room, seated on one side of a table flanked by white academics, pens in hand as if drawn weapons. He was rejected, and he then returned to Rorke’s Drift to take up a residency there.

The ELC at Rorke’s Drift was one of the few facilities offering art training to black artists in South Africa, and in the later years that it was operational, 1967 to 1972, many of the most important black artists to emerge in the following decade trained there, like Bongiwe Dhlomo, who has since become an important visual arts administrator in South Africa, and artists Kay Hassan and Sam Nhlengethwa.

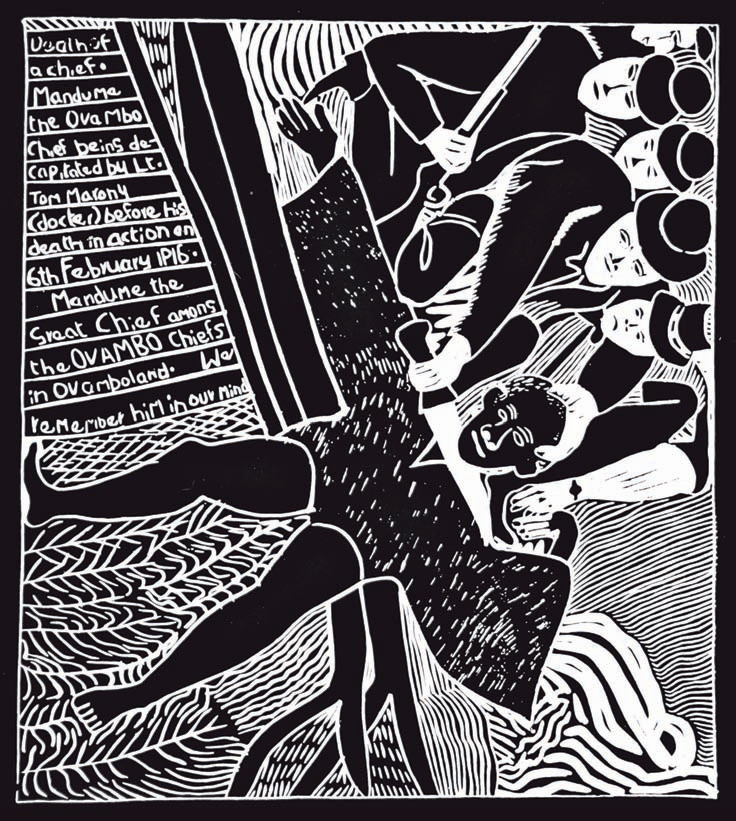

Muafangejo is considered to be one of the country’s greatest printmakers, and his work has continued to be widely exhibited in such exhibitions as Okwui Enwezor’s The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1954–1994, on which his linocut Death of a Chief (1971) was shown.

This harsh critique of colonialism portrays the 1916 killing by British officers of Chief Mandume of the Ovambo tribe. Under Mandume the Kwanyama were the last of the Ovambo peoples to steadfastly resist and remain independent of colonial forces, but the Germans, Portuguese, and South Africans acted together to bring about his downfall. Muafangejo shows the unbalanced chief with arms outstretched, sliding diagonally down the print toward the viewer. Muanfangejo was a Kwanyama.

After he left Rorke’s Drift, Muafangejo returned to Namibia, where he died prematurely in 1987 of a stroke at the age of forty-four. Through such works as Death of a Chief and by virtue of the enormous influence he has had on ensuing generations of printmakers, the artist lives on.

Death of a Chief, Mandume 1971

Linocut

37 x 33.2 cm

Collection: Orde Levinson

© John Muafangejo