In South Africa many AIDS orphans are completely separated from their families when their mothers—who carried societal stigmas because of the disease—die. They are sent to foster parents or institutions or live on their own. The Memory Box Project, started in 2001 by the AIDS and Society Research Unit at the University of Cape Town, sought to give these children a sense of family history by helping the mother to leave behind an archive of memories. In workshops women were shown suggested materials to place in a large cardboard box: sweet messages to their children, a diary of family life, photographs with written descriptions. The activity gave the women a sense of agency and of planning, of being able to provide a tangible emotional legacy.

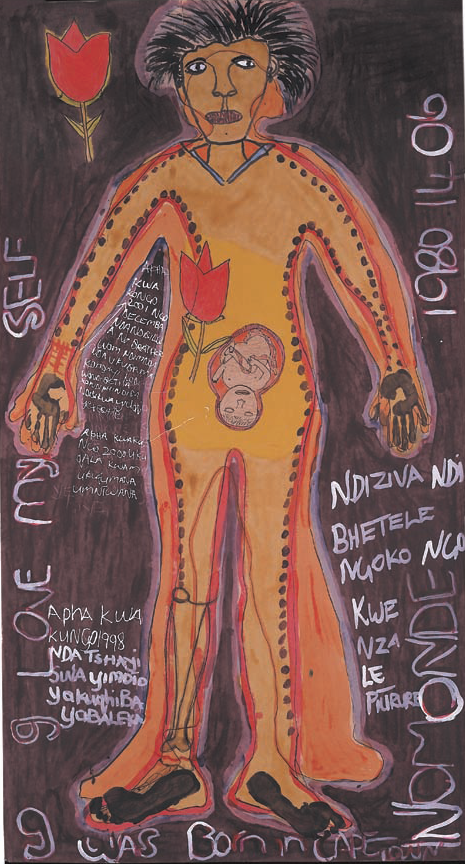

In 2002, in conjunction with the international organization Médecins Sans Frontières, ASRU founded the related Body Map Project. Jane Solomon, an artist with a history of facilitating community art projects, led members of the Bambanani Women’s Group in Khayelitsha in a process of therapeutic “body mapping” at the Khayelitsha Day Hospital in Cape Town. Each woman had her outline traced on brown paper and, using paint and other media, proceeded to draw onto her body chart the contours of her life, marking areas of pain, desire, hope, knowledge, power, and memory. The Body Maps were also used to lead the women through exercises that built a holistic understanding of HIV, including issues such as social support, nutrition, and how to access and adhere to antiretroviral treatment.

Wrote Solomon in the introduction to Long Life (Double Storey, 2003), the book that documented the project, “I was hoping the art works would turn out not merely as illustrations of the powerful stories I expected to encounter, but as something more primal and primary.” The final maps proved deeply meaningful for both participants and those who viewed them.

While many of the women were nervous about adding their names to the completed maps or having them exhibited in public, they have since recognized their role in spreading positive representations of patients coping with the disease. A number have become community AIDS activists and educators. The project has been successfully replicated in Tanzania, Zambia, and Canada.

Although the therapeutic process in and of itself was the primary drive of the project, the power and beauty of the resulting Body Maps have shifted them from the private realm into the public domain of both activism and aesthetics. Indeed, galleries worldwide have exhibited prints of the original Body Maps, editioned by the David Krut Gallery, Johannesburg and New York. These exhibitions have heightened awareness of the individual histories of women who are HIV-positive and brought home the reality of HIV, so often accessed solely, particularly in Western nations, through statistics.

Victoria

Body Maps Project 2002

Mixed media on brown paper

200 x 150 cm

Image courtesy of the AIDS and Society Research Unit (University of Cape Town) and the Bambanani Women’s Group

© The Bambanani Women’s Group

Nomonde

Body Maps Project 2002

Mixed media on brown paper

200 x 150 cm

Image courtesy of the AIDS and Society Research Unit (University of Cape Town) and the Bambanani Women’s Group

© The Bambanani Women’s Group

Nondumiso Hlwele

Body Maps Project 2002

Mixed media on brown paper

200 x 150 cm

Image courtesy of the AIDS and Society Research Unit (University of Cape Town) and the Bambanani Women’s Group

© The Bambanani Women’s Group