Chapter 08 - Punchline: A Grim Humor Holds Up a Mirror to Society

CONRAD BOTES Foreign Body 2007

Wall painting with glass roundels Oil-based paint on glass Dimensions variable

Image courtesy of the Michael Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town

Photographer: Mario Todeschini

© Conrad Botes

“Humor seeks to make light of a dark world or vice versa. It is part of our incessant, courageous struggle to create an imaginative space in which to live more fully,” wrote curator Colin Richards in his proposal for an exhibition of contemporary Pan-African art, to be shown at the 51st Venice Biennale in 2007. “Where hurt and violence can feel generalized and indifferent to the particular, humor always seems ineluctably particular and individual,” he continued. “The sense of humor also distinguishes the human animal from the purely animal. Humor may even be a sign of what it means to be fully human.”

The human and inescapable impulse to laugh is also an impulse to celebrate. In the 1980s and 90s the restrictions that the Nationalist government imposed on certain hard news items criticizing police or state action did not prevent cartoonists from doing so. In an early cartoon by Jonathan Shapiro (aka Zapiro), State President P. W. Botha is portrayed as the puppet of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, Western leaders who might give lip service to the international anti-apartheid movement but who in reality supported the Nationalist government for economic reasons and a perceived anti-Communist stance.

After 1994 the same artists and cartoonists who once exposed the brutality of the apartheid government continued to expose the new government’s weaknesses. They believe that political correctness is the antithesis of the sensibility needed to make a good cartoonist, or artist.

Shapiro, the nation’s most popular cartoonist, tells the story of receiving a phone call in the years in which Nelson Mandela was president, from someone purporting to be the great man himself. Believing it was one of his friends adopting the distinctive Mandela accent, Shapiro demanded several times that the caller identify himself. When he realized it was indeed Mandela, calling to ask for an original Zapiro cartoon for a charity auction, a shaken Shapiro started to apologize fervently for a recent cartoon criticizing Mandela. Laughing, Mandela assured him, “That’s your job, Zapiro. You must do your job.”

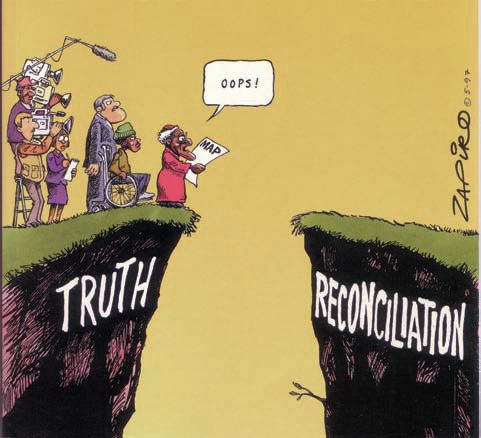

In the finest traditions of cartooning, Shapiro’s best images take a complex situation and present it as an easily understood ideogram, which remains in the mind as a signifier of the situation. When the new government announced the formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1996, to uncover and bring to light the horrors of the crimes of apartheid and the perpetrators behind them, it was with the agenda of opening up and cauterizing the wounds of the nation. Shapiro’s 1997 cartoon showing Archbishop Desmond Tutu, chairman of the TRC, staring at a faulty map indicates with total clarity the flaws endemic in the original agenda.

As part of his 2003 exhibition White Like Me, sculptor Brett Murray worked directly out of the genre of New Yorker magazine cartoons to satirize fumbling white middle class attempts to come to grips with the new social mores that pertain to a supposedly integrated society. In one of his almost six-foot-high reproductions of the cartoons, which the artist cut out of white and black Perspex, fitted together jigsaw style and sanded down to a dull sheen, two suited businessmen face each other across a table. “Are you the other or the other-other or just another other?” one asks of his companion.

Conrad Botes and Anton Kannemeyer were postgraduates in the graphic design department of the University of Stellenbosch when they published the first issue of Bitterkomix, an iconoclastic and irreverent comic book in which they lampooned Afrikaner values of church and home and portrayed graphic sex across color lines. Writing in the South Atlantic Quarterly (Fall 2004), sociologist Rita Barnard reported that at the time one university colleague declared that Kannemeyer “flings the repellent results of his filthy preoccupation with sex in the face of the public.” Simultaneously, appreciative critics declared Bitterkomix to be “undeniably part of our ‘national culture’ ” and insisted that it “belongs in the Africana section of every library.”

The tradition of the comic book is also an integral part of the art practice of Robin Rhode, who often presents the documentation of his performances as a grid of photographs that read sequentially. Using the wall on the street as his blank page, Rhode will draw an object on that wall, then interact with his own drawing, in a comic situation that grows increasingly complex and more difficult for the artist until it ends, as all the best works of this kind do, with a punch line, which leaves his audience smiling in admiration of his skill at bringing about this particular denouement while pondering on the deeper meaning of the work.

Norman Catherine’s grim humor is evident in myriad details of his paintings and sculptures, and painter Robert Hodgins has spent a lifetime deflating egos and shooting down the puffed up. Hodgins takes as his particular targets officials, businessmen of every stripe and color and anybody who might consider themselves superior in any way to anyone else. The old government may have sailed off into the sunset, but there is no shortage of targets for Hodgins’s barbs under the new dispensation.

Which brings us back to the Venice Biennale proposal by Colin Richards. Concludes Richards: “Humor is protean. It enjoys intimacy as much as spectacle. It can be acid, gentle, lyrical, bombastic. It can be a barb, a balm, a bomb. It can be monstrous and unfunny. It always embodies a smile that bites, a laugh that explodes, a grim grin.” An art world—in South Africa, Africa, and beyond—without this leavening would be dull indeed.

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

Zapiro 1987

Cartoon

Image courtesy of the artist

© Jonathan Shapiro

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

Zapiro 1987

Cartoon

Image courtesy of the artist

© Jonathan Shapiro

BRETT MURRAY

Another Other 2002

Plastic and wood

110 x 110 cm

Image courtesy of the artist

Photographer: Alex Bozas

© Brett Murray