Over the years Cape Town sculptor Brett Murray’s work has consistently explored the complex relationships between power and its subjects, often by posing jarring binaries.

In 2007 the artist made a large wall text piece that read OSAMA BIN COHEN for inclusion in a show at the Goodman Gallery, which is in a Muslim section of Cape Town and has many Jewish clients. The gallery considered it to be too potentially offensive to exhibit. Says Murray, “The piece is called Brotherhood, so it is more about the celebration of sameness rather than an attack on difference. My objective is not to insult, it is to provoke. There are profound similarities between the Jewish and the Muslim religions. What was interesting was that the internal discussions around showing the piece were exactly the kind of discussions that I would have liked to have encouraged publicly.”

In the apartheid years the target of much of Murray’s work was the State, but recently he has leveled his sights not only on warmongers in every nation, including the United States, but on the politicians of the new South African government. His new work reflects the impression of many that these politicians’ early ideals of alleviating poverty in the country have given way to a desire to acquire personal wealth and lead an opulent lifestyle.

Murray’s 2008 exhibition at the Goodman Gallery drew parallels with the French court of Louis XVI, in which the courtiers devoted themselves to fine clothing and elaborate entertainments while the peasants starved. In Crocodile Tears, using silhouettes that recall the decadence of the eighteenth-century court immediately before the French Revolution, bewigged, becurled, and becostumed figures cut out of layers of steel coated in gold leaf cry blue tears in relentless streams that pool at their feet.

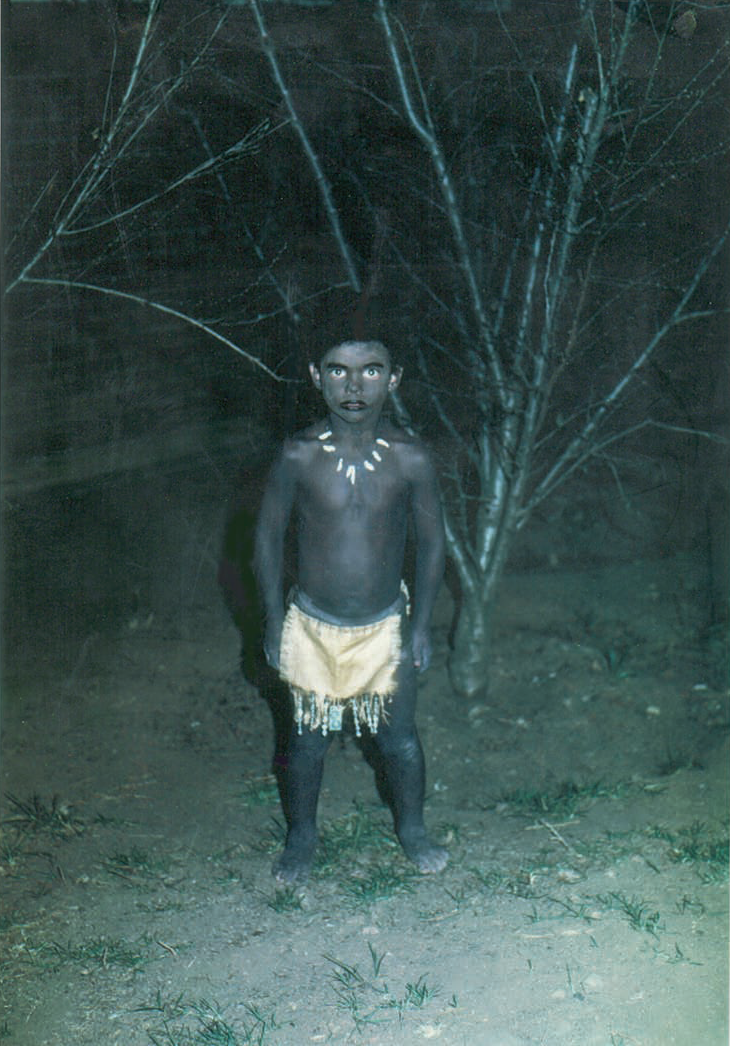

But Murray is not pointing fingers while trying to evade responsibility for his own role in society. Examining the strange complexities of being a white African, a family snapshot of the artist at six years old dressed as a Zulu warrior was used by Murray as an invitation for his Standard Bank Young Artist Award show White Like Me (2002). And on Crocodile Tears Murray again presents a self-portrait to take up his position in the cast of characters he is presenting. Renaissance Man shows the artist as serious-faced suburbanite tending his “land,” naked to the waist except for an unkempt white curled wig and blackface makeup.

“I’m placing myself quite centrally as the one who is not only throwing the stones but ducking them,” says Murray of his role as a white artist accepting complicity in the discriminatory history of his country. “I am conscious that I am present as the victim of my own satire as well as the articulation of it—I am a privileged white South African.”

Crocodile Tears 2 2008

Mild steel, paint, and gold leaf

214.5 x 118 x 10 cm

Image courtesy of the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Cape Town

Photographer: Sean Wilson

© Brett Murray

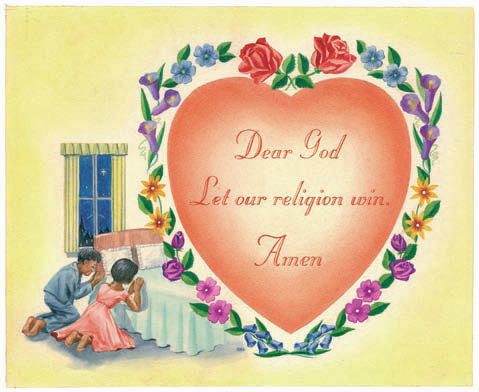

Dear Lord 2005

Digital print on cotton rag paper

37 x 30.5 cm

Edition of 15

Image courtesy of the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Cape Town

© Brett Murray

Amen 2005

Digital print on cotton rag paper

30 x 38 cm

Edition of 15

Image courtesy of the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Cape Town

© Brett Murray

Artist as Zulu, age 6 1967

Photograph

Image courtesy of the artist

© Brett Murray

The Renaissance Man 2008

1015 x 775 mm

Edition of 5

Digital print on cotton rag

Image courtesy of the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Cape Town

Photographer: Sean Wilson

© Brett Murray

Brotherhood (in studio) 2007

Metal and gold leaf

170 x 1250 cm

Image courtesy of the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Cape Town

Photographer: Brett Murray

© Brett Murray