Chapter 09 - The Materiality of Sculpture

NANDIPHA MNTAMBO Europa 2008

Archival ink on cotton rag paper

112 x 112 cm

Image courtesy of the Michael Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town

Photographer: Tony Meintjes

© Nandipha Mntambo

Generally speaking, throughout Africa, after power had been handed over from the colonial masters to a democratically elected constituency, the classic action of the newly free constituents was to pull the old statues, symbols of the oppressors, off their pedestals. In towns like Quelimane, Mozambique, and Kinshasa, Congo, such statues can still be seen today, lying headless on the ground or bundled unceremoniously together in the corner of a forgotten yard.

In South Africa this did not happen. When the African National Congress came to power in 1994 under President Nelson Mandela, the party’s attitude was one of reconciliation and recognition that the painful history of the country should not be forgotten but assimilated into the national memory of the country. Thus, the statues of British monarchs such as Queen Victoria, Afrikaner generals like Louis Botha, and colonial entrepreneurs like Cecil Rhodes were allowed to remain on their pedestals, as if surveying the transforming country.

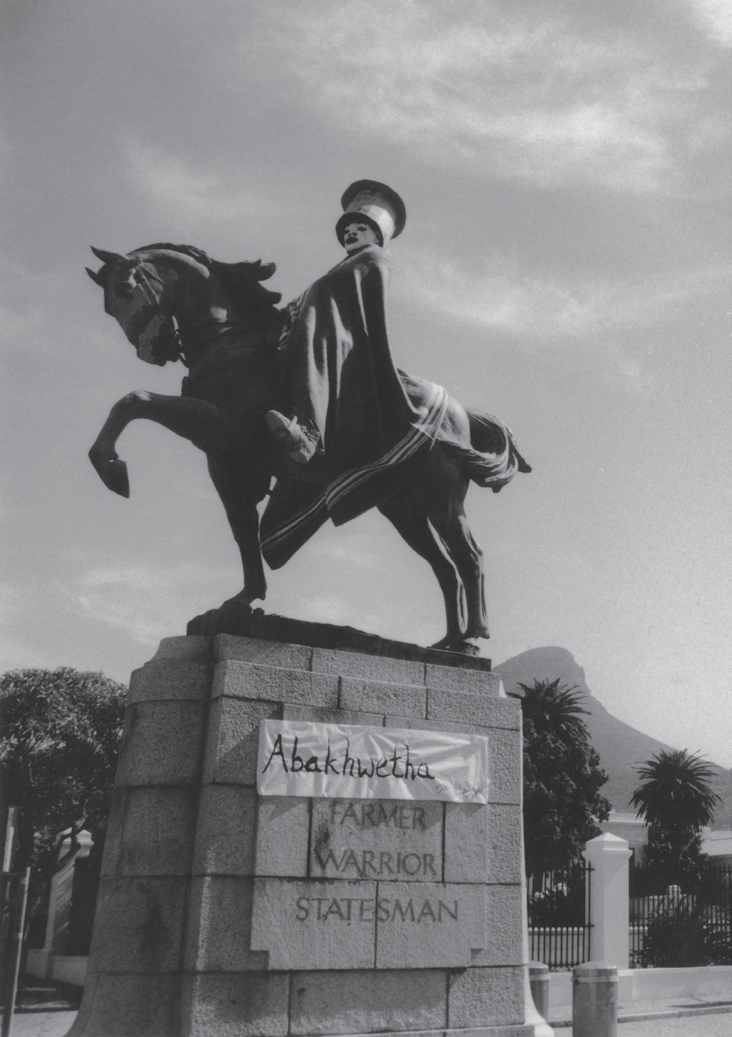

However, in September 1999, to commemorate Heritage Day, a public holiday on which South Africans celebrate their diverse cultural heritage, then-newly launched Cape Town arts organization Public Eye planned a short-term revisionist exercise on such sculptures, inviting artists to “parody, reflect on, subvert, or celebrate” any public sculpture in the city. One of these “revisions’’ made international television news: The proud equestrian sculpture of General Louis Botha, which stands—or rather prances—in front of the Houses of Parliament received a complete change of personality. Artist Beezy Bailey gave Botha’s bronze face a coating of the clay worn by young Xhosa men attending circumcision school, threw a blanket over the general’s shoulders, and made a cardboard headdress to cover the general’s cap—a simple and yet utterly transforming makeover that turned the arrogant military figure into a young black man for a few days.

An equine sculpture that also reflects on South African history in a very different way is Willie Bester’s Trojan Horse III. The piece recalls a notorious incident in Cape Town in 1985 in which police hid in crates on the back of a truck to entrap stone throwers, then jumped out and shot at bystanders. In his work Bester cut and welded his Trojan horse from old bed coils, a tin hat, springs, gas canisters, bicycle bells, and all manner of odd bits of materials unearthed from junkyards and from scrap merchants.

This use of secondhand materials is characteristic of much of the sculpture produced in South Africa, partly for economic reasons, but more important, found materials already have a history, which are layered into the new work. Rather than stemming from an anti-art impulse, Bester’s use of spades, parts of medical cabinets, tools, children’s shoes, fragments of dishes, or old anti-apartheid signs should be seen as authentic pictorial research, a building up of historical energy that could not be achieved by using new materials.

While Paul Edmunds, too, works with secondhand materials—walking the streets of Cape Town, loosening the black and white plastic cable ties that once secured posters to poles, asking his studio mates not to throw Styrofoam mugs away—his obsessive practice requires that whatever he is collecting at that moment has to be the right version of that object. Through patterning and repetition and recycling goods in his artwork, Edmunds explores concepts of good environmental practice.

To re-create a key architectural feature of the lost mixed-race suburb of District Six, demolished by the apartheid government in the late 1970s, Kevin Brand ordered seven tons of rejected cardboard to rebuild the Seven Steps, a meeting place he remembered from childhood. As part of the District Six Sculpture Project of 1997, Brand located his cardboard steps right on their original site.

Also addressing an urban history, in his case, Johannesburg, Stephen Hobbs uses low-tech materials to present a concept of the fast-moving, collapsing and regenerating, endlessly enticing city that is regarded as the powerhouse of Africa.

Wim Botha may use some extremely unconventional materials to carve his sculptures, but the nature of the material he uses is intricately linked with the meaning of the piece. In his long series of book pieces, Botha has accumulated quantities of such publications as official government gazettes, bibles, and dictionaries in four of the eleven official languages of South Africa, and prison release papers and other documents to use as unconventional carving blocks. These publications are bolted together by threaded steel rods to form the block in a way that would allow the information to be available once again should the carved sculpture ever be disassembled. Says Botha, “It is important to me that the possibility of a partial recovery of the text exists.”

This desire to pass on information, even in a constricted form, is shared by Willem Boshoff, whose seminal piece is The Blind Alphabet (1991–95), which privileges blind people over the sighted. Boshoff encloses his small wooden sculptures, each of which illustrates an obscure descriptive word ferreted out of a dictionary, into a pedestal with a closed lid embossed in Braille. Boshoff’s firm instruction is that a sighted person may only view the sculpture in the company of one who is blind and can lift the lid, read the Braille, and explain the derivation of the sculpture to the viewer.

Coded information hovers again enticingly in the immaculate woven structures of Siemon Allen, seemingly erected to create a mirrored barrier between the viewer and the rest of the space. Allen uses old videotape in his weavings, both for their techno gleam and for the provocation of letting the audience know that on this unspooled tape stories and images once existed that will never again be screened.

Working in a different sphere from her white male peers, Nandipha Mntambo selects the organic and the sensual as both subject and medium. She molds cowhides to casts of her body to make suspended forms that suggest an interrogation of both traditional concepts of femininity and the long traditions of owning cattle in Africa.

Alan Alborough normally works with very clean and pristine industrial materials for his playful and enigmatic pieces. For Heathen Wet Lip (1997) the artist used preserved elephant ears to reflect again on the heritage of the white man in Africa.

Doreen Southwood re-creates the curtain of her grandmother’s house in steel, fabricating the intricate brocade designs in tiny steel nuts and bolts held by magnets to a pale blue steel sheet.

And Jane Alexander builds upon her considerable reputation to create a cast of sculptural characters who travel around the world like a troupe of actors, adapting their performance to the situation and location in which they find themselves.

Expensive materials are not on the shopping list for the artists who make sculpture and installations in South Africa. For them, whatever is close at hand, whatever carries a former history or an associative context is potentially of interest as an element in a powerful new work.

BEEZY BAILEY Abakhweta 1999 P.T.O. Sculpture Project, Cape Town Blanket, clay, cardboard, existing statue of Gen.

Louis Botha Image courtesy of the artist

Photographer: Beezy Bailey

© Beezy Bailey