Johannes Phokela likes to play the fool. Acting as a painterly court jester, he addresses dark subjects via satire, parody, and metaphor. The joke here is on the baroque tradition of Western painting: the baroque style is most closely associated with the Enlightenment, the age complicit with the beginnings of European colonial conquest and its happy marriage to modern capitalism.

Phokela appropriates scenes from the Baroque masterpieces of Breugel, Rubens, de Gheyn. He pares down their palettes to that of an underpainting or inserts black figures into scenes. By doing so, he is more than thumbing his nose at the colonial master: Phokela often adds the very geometrical grid that underlies Cartesian logic and modernist notions of autonomy, precisely so as to undermine its imposition of order onto experience.

Born in Soweto in 1966 and studying art at the Federated Union of Black Artists (FUBA) in Johannesburg during the turbulent 1980s, Phokela concluded his studies at the Royal College of Art in London and lived in London for many years, returning to Johannesburg in 2007.

In 2003 an exhibition spanning eight years of Phokela’s production traveled from London’s Café Gallery to Johannesburg and Cape Town. In Cape Town Phokela’s work was displayed at the Old Townhouse, which houses the Michaelis Collection, the largest local collection of seventeenth-century Dutch art, and thus a particularly appropriate venue for Phokela’s work. Critic James Gaywood wrote that Phokela “remains fully aware of his political significance, a black South African artist working in London, making paintings in the classical tradition of Western art.”

However, Phokela’s engagement with the medium of paint extends beyond this simply polemical gesture. Working in a very different style, Phokela sometimes covers an entire canvas with a series of controlled cuts, which he then stitches closed. Paint seeps and bleeds through the stitched cuts, suggesting, perhaps, a censored or concealed image.

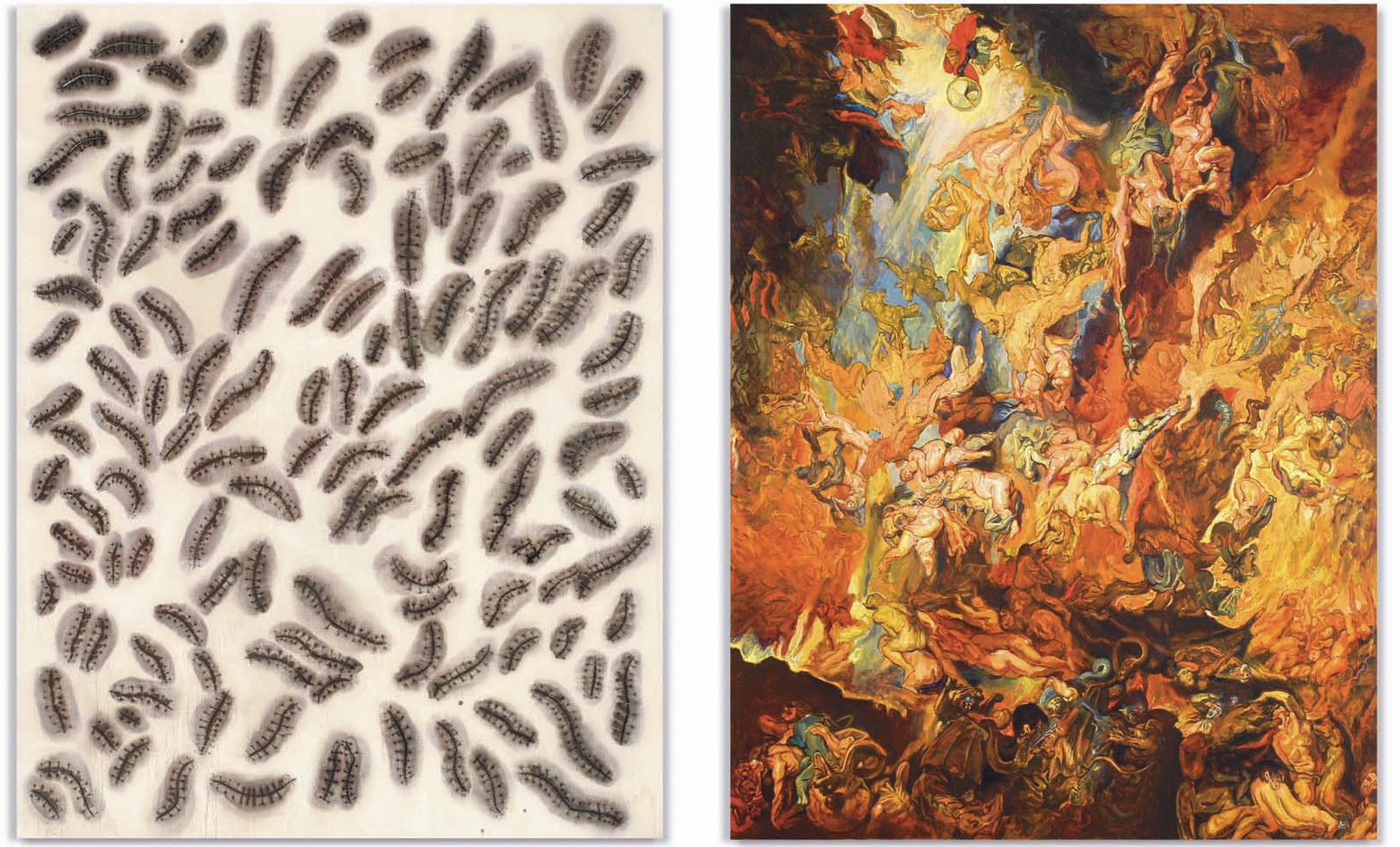

In Personal Affects at the Museum for African Art, New York (2005), Phokela showed a diptych that incorporated both these styles. One of the two paintings in Fall of the Damned (1993) is an appropriation of Rubens’s The Descent into Hell of the Damned. Phokela’s masterly depiction of falling bodies hurtling through the air to a subterranean cave is painted in grand classical style. The second painting of the diptych, installed at right angles, mimicked the falling bodies with a series of shapes or objects resembling Mopane worms, a traditional delicacy eaten in South Africa. It appeared to be a reduction of its partner to its essential compositional elements. At the same time it recalled, perhaps, the biblical phrase “ashes to ashes and dust to dust”: the state to which we must all return.

Again, in having rendered his appropriation of classical painting with consummate skill, Phokela had undercut its heavy drama with a humorous painterly response.

Fall of the Damned 1993

Diptych

Left-hand panel: oil on canvas

Right-hand panel: canvas,

rabbit skin glue, cotton twine, enamel paint

287.5 x 223.5 x 4 cm each

Collection: Museum for African Art, New York, 2004

Image courtesy of the Michael Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town

© Johannes Phokela