Perhaps nothing in the field of nutrition is more controversial than the recommendations surrounding dietary fat. How much of our diet should be fat? What kind of fat should we eat? From what foods should we get our dietary fat? These and other questions are on the minds of many people interested in improving their health through the foods they eat. And yet, even with the thousands of studies that have been conducted on dietary fat and health, there remains substantial disagreement among scientists and health practitioners about the answers to these questions. I should mention that there are a few points of agreement (e.g., trans fats raise the risk of heart diseases; omega-3 fat is essential; replacing fat with sugar and refined carbs isn’t an improvement), but it’s clear the scientific uncertainty has made much of the public vulnerable to the huckstering of self-proclaimed health gurus. Indeed, spend five minutes on the internet and you can find someone espousing the virtues of nearly every source of fat on the planet, from coconut oil to olive oil to bacon fat to butter.

This overwhelming array of opinions parallels a controversy in the field of sports nutrition, too. For many years, carbohydrate was considered the most important macronutrient for performance, especially for athletes doing prolonged endurance exercise. Over the past two decades, though, more and more studies have questioned whether this dogma is truly justified for all athletes and situations. Today, the overall evidence indicates that both high-carbohydrate and high-fat diets have their place in sports, but as with many subjects, our hyperpolarized world—partly driven by social media—has created entrenched camps of athletes and coaches who unwaveringly commit to high-fat diets even in situations where they may do more harm than good. Similarly, there are those who dismiss the potential of high-fat diets even though they may offer benefits in certain situations.

Ultimately, my goal with this chapter is to cut through some of this confusion and provide a balanced, scientifically informed perspective on the topic of dietary fat, athletic performance, and gut function. As you’ll come to see, the utility of high-fat diets—like many nutrition strategies—is context specific. First, though, I will briefly review what the heck dietary fat is and how much of it the average person eats.

FAT DEFINED

The term fat is typically used to describe triglycerides, a type of lipid. A lack of chemical polarity prevents lipids from dissolving in polar substances like water, unless you have a third substance with both polar and nonpolar features (i.e., an emulsifier) to add to the mix. This poor solubility in polar substances such as water is the unifying feature of all lipids (triglycerides, cholesterol, phospholipids, etc.), which can otherwise have rather different functions in your body. Of these lipids, triglycerides are the type found most abundantly in the diet and the human body.

Dietary fat is what makes many of our favorite foods so palatable, and that’s one reason food companies started adding sugar to many products during the height of the low-fat diet craze in the 1990s. When you remove fat from a food, it tastes like cardboard, and some extra sugar can go a long way toward keeping the food edible. For survival reasons, we probably evolved as a species to derive a certain pleasure from eating calorically dense foods, and at a whopping 9 kcal per gram, fat packs one heck of an energy punch.

Based on surveys that accurately reflect the American population, the average adult eats about 80 grams of fat each day (700 kcal’s worth), an amount that’s been fairly stable over the past four decades.1 To give some context, that’s about the amount of fat you’d find in 6 tablespoons of olive oil or almost an entire stick of butter. Bear in mind, though, the dietary fat requirements of athletes can differ greatly from those of the general public. For an ultrarunner who burns over 10,000 kcal on the day of a 100-mile race, eating the average American’s 80-gram allotment of fat wouldn’t even supply 10 percent of their energy needs. For these types of athletes, extra fat in the diet can be an efficient means of meeting energy demands without having to put away a mountain of food. That said, these athletes need to be cognizant of when fat-rich foods are eaten, because the timing of fat ingestion is key when it comes to preventing several gut symptoms during exercise, particularly those that impact the upper gut (nausea, fullness, reflux, etc.).

FAT CONSUMPTION BEFORE AND DURING EXERCISE

There are several reasons it’s usually ill-advised to wolf down fatty foods just before and during exercise. Because we evolved to readily stockpile fat during periods of energy abundance (which is basically 100 percent of the time in today’s developed world), there’s no real risk of running out of fat stores during exercise. In addition, dietary fat tends to pump the brakes on gastric emptying more than protein and carbohydrate, in large part because fat is such an energy-dense nutrient. As a rule of thumb, the more energy-dense a food is, the longer it takes to leave your stomach. Notably, protein and carbohydrate contain roughly 4 kcal per gram, or about half as much as fat.

In a way, the rationale for limiting fat consumption during exercise is similar to the reason for restricting fiber. Undoubtedly, fatty or fibrous food sitting idly in your stomach is a recipe for gut distress. With that said, tolerance to fat ingestion—much like fiber ingestion—is influenced by exercise intensity, and athletes partaking in relatively low intensity exercise over very long periods (e.g., a 24-hour race or multiday event) don’t need to worry as much about fat causing adverse gut symptoms. A study of competitors from a 160-kilometer race supports this idea; runners consumed about 0.5 grams of fat every kilometer, equating to about 80 grams of fat over the entire race, and average fat intakes weren’t different between runners who did and did not experience digestive troubles.2

Beyond restricting fat during exercise (except possibly during lower intensity activities), avoiding greasy foods immediately before exercise is a prudent decision as well. A study of male triathletes, for example, found that fat intake during the 30 minutes prior to a half-Ironman race was greater in those who vomited or had an urge to vomit than in competitors without such symptoms.3 The most obvious explanation for this finding is a delay in stomach emptying and the release of cholecystokinin. Furthermore, a study published in the journal Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise found that only about 10 percent of the fat in a meal consumed one hour before cycling eventually got burned during exercise.4 This is because most of the fat you absorb is transported in your blood as a part of chylomicrons, which don’t readily release triglycerides to the muscle during exercise.5

While limiting fat consumption within an hour of exercise is sensible, what to do two to four hours beforehand is less clear. Carbohydrate ingestion during this window clearly improves subsequent exercise performance in comparison to fasting or to consuming an energy-free placebo, but studies that have compared feeding carbohydrate- and fat-rich meals containing an equal amount of energy several hours before exercise have often failed to find differences in performance. Several of these studies, conducted from the mid-1990s through the mid-2000s, showed that while the composition of a pre-exercise meal (fat versus carbohydrate) does alter levels of glucose, insulin, and fat in the blood, these metabolic differences don’t necessarily translate to changes in performance.6–8

Furthermore, the risk of nausea, vomiting, regurgitation, and excessive fullness from eating a high-fat meal is probably pretty low if you eat a few hours before exercise, since most of the fat will have left your stomach by the time you get going with exercise. One study fed men two meals (both 600 kcal) with drastically different fat contents (71 percent versus 7 percent) and tracked how quickly each meal vacated from their stomachs.9 Despite being equivalent in energy, it took 140 minutes before half of the fat-laden meal had emptied, contrasted against 100 minutes for the low-fat, high-carbohydrate meal. Given that most athletes don’t eat meals that are 70 percent fat, we can extrapolate that the bulk of a moderate-fat (35–50 percent of energy), moderate-energy (500–800 kcal) meal would empty from the stomach after a few hours. The theoretical representation of how the timing of moderate-to-high-fat meals impact the risk of gut symptoms is shown in Figure 5.1.

One caveat to keep in mind is that eating a fat-loaded meal that’s also an energy bomb (more than 1,000 kcal) would prolong gastric emptying time more than usual and could certainly cause gut issues. In more simplistic terms, eating an entire Chipotle burrito with extra sour cream and guacamole probably is not the savviest pre-event fueling tactic, even if you eat it several hours before hitting the start line. Remember Michael Scott’s Dunder Mifflin Scranton Meredith Palmer Memorial Celebrity Rabies Awareness Pro-Am Fun Run Race for the Cure? (If not, you really, really need to binge-watch The Office.)

figure 5.1PRE-EXERCISE FAT INGESTION

This theoretical representation shows the likelihood of gut symptoms when consuming meals at least moderately rich in fat at various points in time before exercise.

CHRONIC HIGH-FAT DIETS AND PERFORMANCE

Although high-carbohydrate diets are a mainstay for most high-level athletes engaging in heavy training and intense, prolonged competition, interest in high-fat diets remains robust, particularly among ultraendurance athletes. Unfortunately, the cupboard of science is pretty bare on this topic, which is largely because it’s incredibly difficult to recruit participants for controlled experiments that involve multiple exercise trials lasting several hours or more. (Who’s up for staring at a lab wall and getting poked and prodded while exercising for five straight hours?) Even so, there’s some evidence that high-fat diets can improve (or at least not harm) performance in competitions that last more than a few hours.10 This is largely due to the fact that competitors in these events exercise at lower percentages (relatively speaking) of their VO2max and are more reliant on fat burning. Examples of ultra-athletes who have reportedly had success on higher-fat diets include Zach Bitter (current 100-mile world record holder) and Timothy Olson (two-time winner of the 100-mile Western States Endurance Run).

Still, there’s little reason to eat a high-fat diet if you’re regularly training for and competing in events that involve high-intensity (75 percent-plus of VO2max) exercise. This sort of pedal-to-the-metal activity relies heavily on carbohydrate burning, and while eating loads of butter, Ben & Jerry’s, and guacamole would undoubtedly upregulate your capacity to rely on fat for energy, it would also simultaneously impair your ability to utilize carbohydrate.10 A downtick in carbohydrate burning may not hurt an ultrarunner much during a 100-kilometer race, as the relative exercise intensity over that distance is lower, but it would likely slow an elite runner exercising at 75–90 percent of her VO2max for any substantial length of time. Indeed, a recent experiment led by renowned sports scientist Louise Burke showed that, in comparison to following high-carbohydrate diets, following a very-low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet impaired carbohydrate burning, reduced exercise economy, and hurt 10-kilometer race performance in elite racewalkers during an intensified three-week training period.11 To give some context for those of you who don’t closely follow racewalking, a 10-kilometer race lasts about 37–45 minutes for elite athletes. There’s obviously a big difference between a 10-kilometer race and races that last many hours, so perhaps you’re wondering at what distance or duration a high-fat diet becomes potentially advantageous. Although I can’t give you a precise threshold, races that last more than a few hours are the most likely candidates.

CHRONIC HIGH-FAT DIETS AND THE GUT

If you ever decide to shun carbs in favor of a high-fat lifestyle, what can you expect with respect to gut function and digestive symptoms? By default, most people following high-fat diets (though not all) cut back on nature’s stool bulker, fiber, primarily because fruits, starchy vegetables, and whole grains are replaced with low-fiber, high-fat foods. This avoidance of fiber leads to less stool productivity in terms of total output and the frequency with which a person answers the call of nature. In one study, total stool weight dropped by about 27 percent after participants followed a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet for eight weeks.12 In addition, participants on the low-carbohydrate diet had reductions in counts of bifidobacteria, microorganisms that are important for the health of the digestive system. On the other hand, the low-carbohydrate dieters reported breaking wind less often, which makes sense given that the products of fiber fermentation include methane, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide.

Whether these changes in gut function ultimately influence exercise performance is uncertain and likely depends on the athlete and the situation. If you’re experiencing severe flatulence, bloating, or urges to go number two during training and competition, then a high-fat, low-carbohydrate (and low-fiber) diet could reduce these symptoms. This potential benefit needs to be weighed against the growing—albeit preliminary—evidence that avoiding dietary carbohydrate and fiber alters the gut microbiome in ways that may not be optimal for gut health in the long run. Moreover, diets low in or devoid of fruits and vegetables may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and some cancers.13 And while nonstarchy vegetables can certainly be eaten in abundance on low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets, they’re sometimes neglected in athletes who aren’t vigilant with their nutritional choices.

In the end, the utility of high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets for managing gut issues may be similar to that of low-FODMAP diets. If you’re regularly bothered by excessive flatulence and bloating, then temporarily eating a higher-fat diet could, in principle, mitigate the severity of these symptoms during competition. On the other hand, high-fat diets may undermine performance during competition that takes place at or above 70–75 percent of your VO2max, especially if the event is expected to last more than 30 minutes. Much like with other nutrition strategies, athletes interested in these diets should trial them to determine their individual responses with respect to gut function and exercise performance.

MEDIUM-CHAIN VERSUS LONG-CHAIN TRIGLYCERIDES

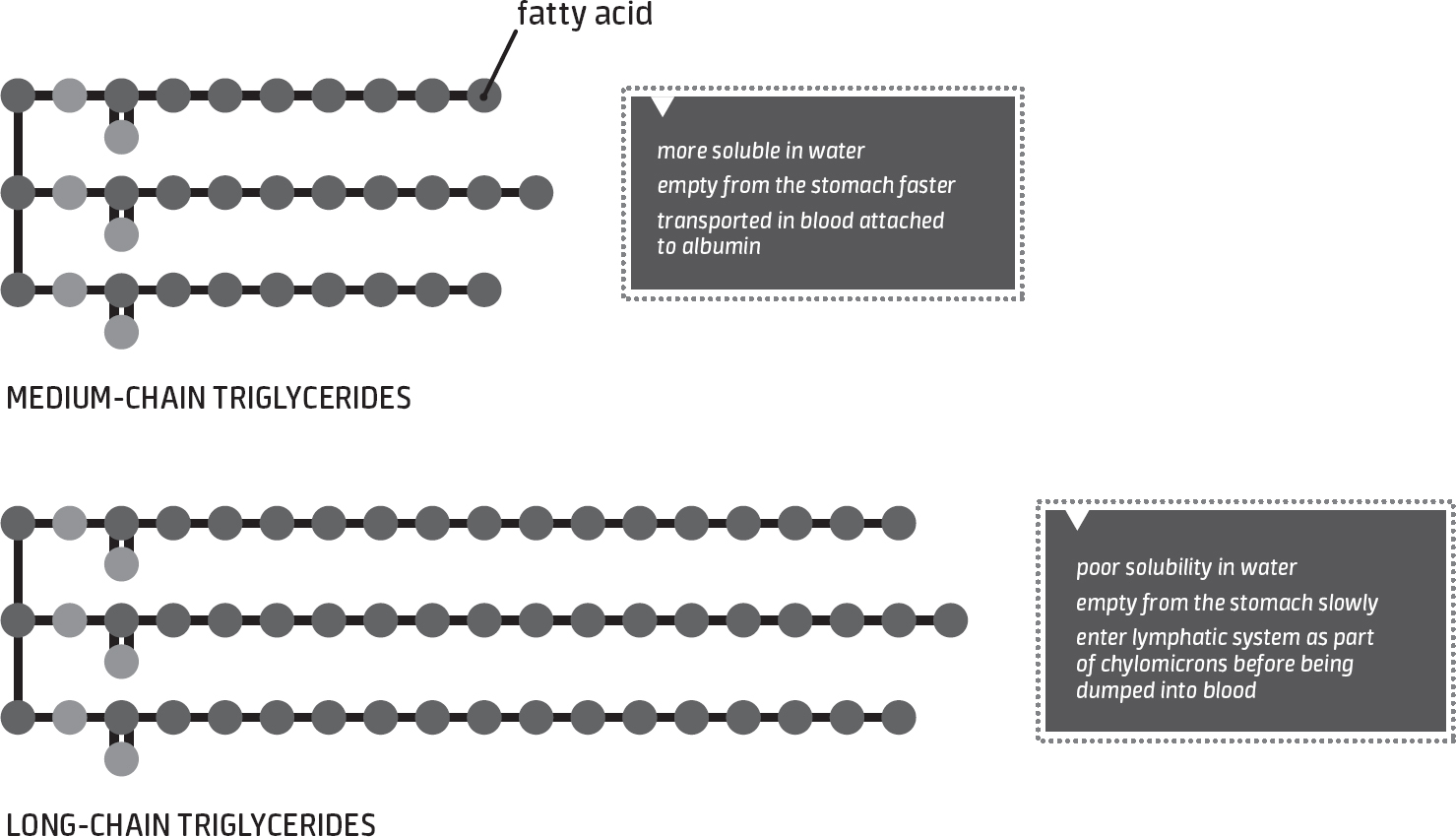

Triglycerides are made of a three-carbon molecule called glycerol, which serves as the backbone of the triglyceride molecule, and three fatty acids. These fatty acids are essentially carbon chains that vary in length from a few carbons to several dozen, and their length determines whether they are considered short-chain, medium-chain, or long-chain fatty acids. In the previous section, the discussion of dietary fat’s influence on gut function was based on the assumption that people primarily eat fat as long-chain triglycerides,5 which make up 90–95 percent of the triglycerides in the average diet. Foods rich in long-chain triglycerides include fatty fish, nuts, olive oil, and fat-rich animal meats. The remaining small percentage of dietary triglycerides comes mostly in the medium-chain variety, which have different physiological properties than long-chain triglycerides (see Figure 5.2) and are found in coconut oil and palm kernel oil and to a lesser extent in dairy products.

Most of the fat you ingest within hours before exercise isn’t burned for energy. Because they’re insoluble in water, long-chain triglycerides from food must first be incorporated into chylomicrons before they can be dumped into your blood. Even before chylomicrons enter your blood, however, they first go through your lymphatic system. From there, they ultimately reach the blood circulation at veins located under the collarbone. Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), in contrast, are more soluble in water and don’t need to be incorporated into chylomicrons before being dumped into blood. Instead, fatty acids from MCTs—which typically range from 6 to 10 carbons long—can enter your blood directly and are usually transported bound to the protein albumin.5

Another major difference between long-chain and medium-chain fats is the rate at which they exit your stomach. A seminal study in Great Britain showed that fatty acids equal to or longer than 12 carbons are more potent than shorter fatty acids at hindering stomach emptying.14 Receptors in your small intestine detect these long-chain fatty acids and tell your body to release hormones such as cholecystokinin that slow the release of chyme from your stomach.15 This is likely an adaptive response that’s intended to prevent too much semidigested food and energy from being dumped into your small intestine all at once.

These differences in the digestion and metabolism of triglycerides led some researchers to speculate that ingesting MCTs would be a good way to boost fat burning during exercise without causing gut problems. A little over a dozen studies conducted between 1980 and the early 2000s—several of which were led by physiologist and Ironman triathlete Asker Jeukendrup—fed athletes variable amounts of MCTs either before or during exercise in an attempt to favorably alter metabolism and performance. While some of these studies showed that ingested MCTs can be burned during exercise, the majority found no differences in overall fat metabolism, nor did they find improvements in performance.5 What’s more, large single doses of MCT oil (perhaps more than 2 tablespoons), or smaller dosages (about 2 teaspoons) taken every 15 to 20 minutes during exercise, can cause nausea, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea. In one of the earliest studies on the topic, exercise physiologist John Ivy and his colleagues found that 100 percent of their subjects developed abdominal cramping and diarrhea when 50 grams or more of MCTs were fed an hour before exercise.16

figure 5.2TRIGLYCERIDE CHAIN LENGTH

In comparison to long-chain triglycerides, medium-chain triglycerides empty from the stomach more quickly and are absorbed directly into blood circulation.

These digestive side effects can ultimately blow up a performance on race day, as was shown by a later study out of South Africa.17 Cyclists completed two roughly five-hour trials, one of which involved consuming a 10 percent carbohydrate beverage, while the other involved consuming a 10 percent carbohydrate plus 4.3 percent MCT beverage. After four and a half hours of cycling at a moderate intensity, performance was assessed by having the cyclists complete a set amount of work as fast as possible. While few gut symptoms were reported when the cyclists consumed the carbohydrate-only drink, half of them complained of such symptoms when MCTs were added to the beverage, and these symptoms probably contributed to the additional time that was required for them to complete the performance test when receiving the MCT beverage (14:30 versus 12:36 minutes).

It’s not completely clear why MCTs wreak havoc on the gut at high doses, but it may be because they increase osmolality in the lumen. Just like with carbohydrate malabsorption, a surge in osmolality can trigger fluid secretion into the lumen, leading to a bad case of the trots. Intriguingly, a person’s ability to handle MCT ingestion may improve over time with repeated exposures over several days or weeks.18, 19 Starting with small doses (say, 2 teaspoons per day of MCT oil) and increasing by that same amount every couple of days may further improve gut tolerance.20

Even if tolerance to MCT ingestion can be improved, there are still no scientific data that strongly justifiy consuming MCTs before or during exercise. As a result, it’s probably best if most athletes focus instead on established strategies for augmenting performance—carbohydrate ingestion, caffeine ingestion, and proper hydration, to name a few.