Figure 7.1 New inventions offered talk functionality beyond signaling, which adapted push buttons for telephones.

Source: Sears, Roebuck and Co., Electrical Goods and Supplies, ca. 1902. Image courtesy of Collections of the Bakken Museum.

How many of our banks and stores and oil stations have the handy, little, ever-ready button on the job for summoning aid—without the knowledge of the thug—when the unexpected hold-up man appears?1

As push-button light switches gave way to toggle or tumbler switches, so too did various constituencies begin to deliberate on the merits and limitations of push buttons in other contexts. In particular, breakdowns in push-button communication in households and offices routinely continued to occur—whether because of the willful disobedience of those receiving a call or user error, prompting modifications to buttons.2 As in years prior, many expressed indignation about the disparities between manual and digital laborers—those who toiled with their hands versus those who managed the work of others (the pushing and the pushed). Critiques focused primarily on a sense of increasing distance made more prominent by the act of pushing a button as a summons. One concerned party wrote to the Magazine of Business (1906) about a printing shop that had “almost been wrecked on such a little matter as a push button.”3 The troubled writer recounted how a manager replaced the business’s original owner, who died after thirty years of dedicated service and hands-on interactions with employees. The young manager with his “new ways” contented himself by dealing with the business through a closed office door and a series of buttons at his fingertips—keeping himself out of view from his workers. After a short time in the post, the author revealed, most of the staff quit and a notable set of clients took their work elsewhere. “It was all due to the push buttons,” the writer lamented.4 According to the piece, push-button communication had physically and emotionally separated the manager from personnel and their day-to-day operations, creating an alienating effect. Employees viewed pushing buttons to direct others’ movements as inherently disconnected from the former way of doing business that involved a kind of affective “touch” based on human contact.

A fictional account written in the same year described a scenario along similar lines, in which the president of a company, so resolute in his desire to be known only as “the Push Button Man,” caused the ruin of a business and himself by virtue of relying on the “whole organ keyboard” of buttons across his desk to keep employees at his beck and call. The story’s moral suggested that, “a push button or two on a man’s desk are doubtless excusable,” but when button pushing came to rule one’s way of doing business, everyone suffered.5

In part, these tales reacted to blatant nepotism in workplaces that led to easy promotions for some and a sense that newly appointed leaders often let their positions of status go to their heads. Indeed, an editorial (1907) about the call button used to summon railway employees made an elaborate case for the ways that push buttons could inflate a manager’s ego, causing him to lose sight of his relationship with and obligation to his employees: “With a finger board nicely arranged with numbered buttons, a certain class of men have become charmed into an exclusive egomania,” the author suggested. “The button has, by reason of its magical properties to charm, led some men to forget the courtesies of life and that all knowledge is not confined to any one man, and further, that no matter how wise, there is some one who knows more, and that person may be poor and may be humble.” In a dramatic flourish the writer concluded, “Faithful little button! you speed your message, ‘come to my office at once,’ with no idea of the heart burns and injured pride that may follow your call. Wise is the man who uses your assistance simply to dispatch business, and grows not into vanity as you run your errand.”6 Although the button seemed “innocent,” according to this observer, communication in a workplace could quickly snowball into a power struggle at the hands of a puffed-up manager. The author, here, imbued buttons with “charming properties” that seduced their pushers to use and abuse them without consideration of the human beings, whom did not occupy the same social station, at the other end of the call.

Another editorialist came to a similar conclusion, worrying that an employee promoted to a branch manager would give in to his “push button inclinations” and, spoiled by the convenience, would no longer remain an “active fighter for business.”7 Journalist Herman J. Stich (1911) referred to these managers, born out of the efficiency movement, as “push-button gents” and “buzzer-pushing maniacs,” known for being “unpopular,” “ineffectual,” and “impermanent.”8 It is important to remember, however, that this push-button act constituted a privilege offered only to some. Just as employees lamented their role in responding to the call, others remarked at the injustice that only some had access to these buttons. One woman in a newspaper editorial, for example, lamented that, although her husband could push buttons at his desk all day, sending away anyone who bored or displeased him, she asked, “Could I have push-buttons around where nobody could see me push them? Of course I couldn’t. Men just have everything their own way in this world, and I wish I’d been born a man, I do.”9 Tension persisted between accessibility and access, as well as between the idealized view of button pushers as docile, feminine creatures uplifted with a mere touch, versus their actual experiences as women in constrained social circumstances.

Whereas buttons could conjure magical effects in other contexts, those buttons pushed for business—that required someone to reply to the summons—triggered continued outrage among the workers put out of view until needed. In the words of one fiction writer (1912):

Well, in these days the gentlemen who are so eager to be very rich have constructed a button—the corporation. It gives them their dearest wish—wealth and power. It removes responsibility away off, beyond their sight. They do not hesitate. They press the button. And then, away off, beyond their sight, so far from them that they can pretend—can make many believe including themselves—that they really didn’t know and don’t know what the other consequences of pressing the button are—away off there, as the button is pressed, people die, people starve, babies are slaughtered, misery blackens countless lives. The prosperous, respectable gentlemen press the button. And not they but the corporation grabs public property—bribes public officials—hires men they never see to do their dirty work, their cruel work, their work of shame and death.10

This notion of putting the “dirty work” out of the way by concealing it from view strikingly resonated with a broader project to make push buttons the “faces” of everything good, easy, and simple. The mess, whether it took the form of electrical wires, a servant, or an employee, could remain conveniently at a distance and out of sight. In this regard, push-button communication injured relations because it seemed to put button pushers “out of touch” from those they pushed.

Many communicative problems also stemmed from a lack of feedback, as the person pushing a button often had no way of knowing whether the button conveyed a signal from a distant location.11 A variety of technologies called “indicators” thus entered the market to create greater transparency and accountability between the button pusher and the “pushed.” Indicators often employed vibration as a form of tactile or auditory feedback. For example, one model worked “with a vibrator concealed in the base of the button and makes a clicking noise which is plainly heard by the person pressing the button. If the vibrator is not heard the person will know that the bell does not ring. Much time and annoyance is saved by this little telltale.”12 These systems in some regard allowed the button to “talk back” to the pusher to indicate whether someone heeded the call on the other end, thereby facilitating two-way communication. They also worked to ease the difficulty of communication across distance, where a pusher was not co-located with the effect of her push.

Despite the benefits of increased feedback, some, such as professor of electrical engineering Clarence Edward Clewell (1916), had begun to argue that push-button devices like annunciators “have a common inherent defect” because “they can do no more than to indicate that a party or thing is wanted.”13 He concluded, “If in addition to the annunciator signal it were possible to communicate over the annunciator wires so as to give further information, the value of the system would be correspondingly increased.”14 This perspective became increasingly common, and over time annunciator systems and electric bells with buttons largely gave way to newer technologies like “intercommunicating” systems, akin to present-day intercom systems. It seemed that “the push button is being elbowed from the high office it has long filled in commercial and domestic life,” as many began to find that “time is becoming every day more valuable, and there is a distinct saving of it when a commission can be conveyed directly to an attendant, and the preliminary summons dispensed with.”15 Although one-way communication could work as well as—or even better than—two-way communication under some circumstances, in others it posed a liability. Intercommunicating devices in closed-circuit environments thus allowed a user at one end to push a button to make an “automatic” and “almost instantaneous” call, which would allow the person at the other end to reply through a simple receiver.16 These setups eliminated the need for outside operators and were particularly advantageous when one central room—like a kitchen—could function as a hub between all other rooms.17

Although some began rewiring entirely for traditional telephones that could make outgoing calls, electrical supply companies also created and marketed affordable ($1-$2) “push button telephones” as tools for intercommunication in the early twentieth century that could fit into existing push-button bell arrangements (see figure 7.1).18 These devices “look[ed] like a push button and act[ed] as a push button” but also functioned as a “complete reliable telephone.”19 The user would not even need an electrician to perform the replacement because installing the button phone only required unscrewing the original push button without disturbing existing wiring. Electric supply companies recommended these push-button phones for “interior installation in private houses, hotels, factories and any building where it is necessary to communicate quickly with the various departments this device can be readily installed and commends itself by reason of its small size and economy of installation.”20

Figure 7.1 New inventions offered talk functionality beyond signaling, which adapted push buttons for telephones.

Source: Sears, Roebuck and Co., Electrical Goods and Supplies, ca. 1902. Image courtesy of Collections of the Bakken Museum.

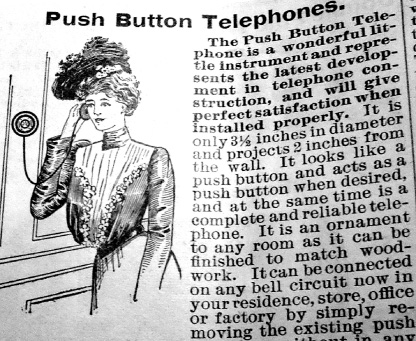

In later years as users adopted such systems, advertisements and informative articles for these telephones emphasized that the homeowner could replace the “old-fashioned” button with a “modern” one that could improve communication in one’s household without disrupting décor or previous bell-ringing apparatuses.21 Much like proponents had lauded the electric button for its ability to make housework and communication less laborious, they rallied a similar campaign for intercommunicating devices. Users were promised that they could talk to any part or person of the house by “simply by pushing the proper button” (see figure 7.2).22

Figure 7.2 Advertisements for “intercommunicating” telephones emphasized that with a simple push, a lady of the house could communicate with any member of her family without expending effort.

Source: Western Electric Company, “Western-Electric Inter-phones,” Collier’s 44 (1909): cxciv. Image courtesy of Princeton University Library via Google Books.

The Inter-phone and other products like it (such as one popular product called the “Metaphone”) capitalized on the concept that a digital commander could accomplish a task with a simple push of the finger, but they took this idea one step further by going beyond signaling through bells and buzzers to the realm of two-way talk. Push button and telephone combinations could potentially make large spaces increasingly intelligible and manageable while making a summons speedier. Indeed, according to the Electrical Magazine and Engineering Monthly, “What a convenience to send a message immediately after your signal instead of waiting to deliver it in person. These tiny telephones are cheap, so are within the reach of all.”23 Railroads increasingly made the transition to intercommunicating telephones, too, so that information could be “conveyed directly to an attendant, and the preliminary summons dispensed with.”24

Intercommunicating campaigns drew on key facets of digital command—reachability (proximity), simplicity, and a gentle touch. Slogans routinely featured reproaches for walking, and instead they advocated for sedentarism in communication as a more efficient strategy. With a Western-Electric “Inter-phone” (1910), for example, the homeowner could save wasted energy from “running up and down stairs or from room to room giving instructions to servants or members of the family” and instead could talk to any part or person of the house “simply by pushing the proper button.”25 Similarly, another manufacturer told potential consumers in later years (1922), “Don’t Walk—Push One Button Once and Talk” (italics original).26 According to the company, “The Stromberg-Carlson Inter-Communicating Telephone System eliminates those needless, wasteful steps. It makes every person, every department in the mill immediately accessible to every other. There is no need to tramp over half the mill to deliver the message.”27 These appeals to efficiency and communication across distance aimed to make pushing buttons a desirable alternative to moving about to conduct one’s business.

As with previous push buttons utilized for bell ringing, however, the intercommunicating system relied on users to negotiate how to communicate according to specific social norms; the ability to talk over the wires—two-way communication—did not inherently improve relationships or represent a “better” way of communicating; rather, it merely represented a different way of communicating.28 As with the transition from bell pulls to bell pushes, usability issues continued to manifest when telephones replaced push buttons in hotels. In one circumstance, a frustrated hotel patron came downstairs to yell at the staff, claiming that he had stood in his room for half an hour pushing a button to ring for a bellboy, only to get no response. The clerk replied that the new system of communication relied on the telephone in the “modern hotel,” and that the establishment no longer used the “old antiquated system of so many rings for this and so many rings for that,” which prompted the guest to walk away meekly.29 In another case, a hotel guest recounted:

It was the first hotel I had ever slept in. On the wall of my room I noticed the button and the sign which read, “Push twice for ice water.” I was a little scared and lonesome, but I couldn’t resist the temptation of seeing how that thing worked. So I pushed the button and stood there for ten minutes, holding the pitcher under it waiting for the water to start running.30

Stories such as this one demonstrated that, despite the seeming simplicity of buttons within reach of all, the user required specific social and contextual knowledge to push buttons appropriately. In addition to confusion, two-way talk could also reinforce hierarchical relationships, just as one-way talk could disrupt these relationships when servants or employees refused to respond as requested.

Of note, push-button communication transpired quite differently depending on the forum and the participants involved. Ringing for servants ultimately became less common because of the more widespread adoption of telephones and as a result of changing dynamics related to service and servants in households. However, push-button signaling—building off of early uses of fire and burglar alarms—became more frequent as a tool for safety. Although household communication could be interpreted as unsatisfactory, given the delay between call and response, it represented a boon in environments like schools, prisons, navy ships, or automobiles; button pushing could marry a desire for simplicity with rapid response. The US Navy recognized this utility of pushes as a mechanism for interactions related to emergency. Call bells played a most important part in facilitating communication throughout ships, with circuits for fire warnings, general alarms, warning signals, and routine interior communication; and vessels were littered with push buttons to make signaling effortless.31 Ships such as the man-of-war “Indiana” were built to showcase the newest and best electrical devices, and electricians often outfitted them with multiple communication technologies ranging from telephones to annunciators.32 According to a report on electrical installations in the US Navy (1907), every living quarter and office should have these tools, and push buttons would “invariably” serve as the actuating switch for annunciators and bells.33

One would find electric buttons throughout the captain’s quarters (in his office, above his bed, and even in his bathroom), as well as in staterooms for employees such as junior officers, warrant officers, and the first sergeant. Others who would have access to buttons with buzzers included the navigator, paymaster, executive officer, and electrical gunner. Mess rooms, pantries, and other common areas also provided electrical communication with water-tight pushes. Ships were, in essence, electrical organisms with “numerous telephones, call bells, buzzers, together with a fire-alarm system and the necessary annunciators; the electric thermostats, general signal alarms, electric engine-telegraphs, to indicate the need of an increase or decrease in the number of revolutions per second, electric lamp indicators for various purposes, helm-angle indicators, revolution and direction-indicators, battle and range-order indicators, besides numerous other important devices.”34 Where speaking tubes were once common on these vessels, sailors found that they could not easily understand speech in the chaotic moments when they most needed comprehension. Instead, a push on a button could provide “clear, sharp strokes of a bell without mistake and without occupying too much attention.”35 Indeed, the captain of a ship need not worry about shouting his orders into the wind and could stay securely in “his nest of solid steel” and transmit his orders with a touch, hearkening back to efforts to keep digital commanders at a remove from their employees.36 Sailors could project warnings with electric horns too, made specially to withstand high-pressure and high-voltage situations.37 To maintain the many circuits required for button pushing, which connected buttons and bells across rooms and decks, naval electricians were expected to have extensive knowledge of their construction and repair.38 Among the many adopters of push-button communication tools, the US Navy certainly stood at the fore for its comprehensive use of one-touch signaling.

Around this time in the early twentieth century, other institutions began experimenting with push-button signals for laypersons in case of emergency. These devices combined the communicative purpose of push-button bells with the automaticity of consumer and factory machines. For example, educational institutions began using button-activated “Automatic Electric Clocks” that would sound alarms in every hallway and on every floor; these institutions also began practicing fire drills to prepare for an actual emergency event.39 Factory buildings likewise embraced fire alarms, with some complex ones that allowed a person to press a button marked “East” (the location in the building of the fire), which would then illuminate the letter “E” on all of the boxes in the building to alert residents.40 Yet another device married a push button with a thermometer that would automatically give notice should a room reach a danger point from fire. Its manufacturer boasted that not only did the button function as a normal push for routine communication purposes, but it could also save lives.41 Despite (or perhaps because of) the importance of alarms in these contexts, these buttons occupied a complicated position as “touch” and “don’t touch” controls—those who maintained them worried about false alarms, mischief, and misuse. As a result, emergency buttons were often put behind glass barriers. Glass could not only make buttons unavailable for uses deemed unnecessary or harmful, but they could also increase the severity of punishment for those who disturbed them, increasing charges from a misdemeanor to a felony for destruction of property.42 As with all kinds of buttons, accessibility and reachability often led to a sense of vulnerability that buttons could fall into the wrong hands.

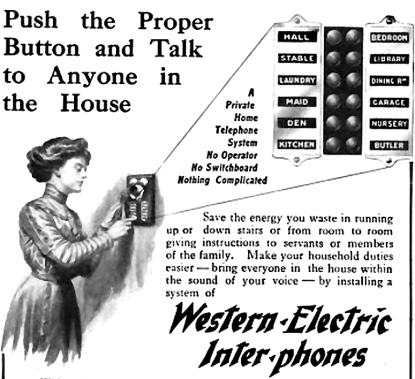

The potential for misuse did not make alarm buttons any less common, however. Numerous button-powered devices that cropped up were meant to serve as signals for police and other emergency officials; in fact, by 1915, inventors filed more than 300 patents for fire alarms alone.43 Among these, Superintendent Kleinstuber of the Milwaukee police department patented a push-button device that one could affix to a lamppost to contact police either day or night.44 An article recounting the merits of the mechanism noted that, in addition to everyday uses, buttons could also act as signaling mechanisms for railroad engineers on course for an accident.45 Fire alarm boxes began to appear routinely on streets and were triggered by a push or pull (see figure 7.3).46 As they evolved, these boxes were considered “altogether automatic” and could even ring alarms directly in the homes of firefighters.47

Figure 7.3 Fire alarm boxes featured red buttons, precursors to prevalent “panic” or emergency buttons of later years. These interfaces associated pushes with warning, danger, and instant control.

Source: “Fire Alarm Shows Exact Location of Fire,” Popular Mechanics 19, no. 6 (1913): 780. Image courtesy of Google Books.

In domestic contexts, alarms were viewed as indispensable in some homes—primarily wealthy ones, to achieve panicked communication across distance. The homeowner could employ electricity by installing a button in the master bedroom, which, when connected to all the rooms of the house, could instantly flood a room or hallway with light to impede “the enterprising burglar [who] comes-a-burgling.”48 However, these alarms did not exist without problems. Because burglar alarms required syncing up a user’s quick reaction with a properly working signal and a response from emergency officials, they were often perceived as unreliable or difficult to manage: “There are as many kinds of burglar alarms as there are burglars—some are good and some are bad, but all of them are troublesome,” author A. Frederick Collins (1916) wrote to aspiring amateur engineers in an issue of Boys’ Life magazine, a periodical for Boy Scouts.49 In addition to user error, if the button or other parts of the mechanism failed, then the alarm would become “worse than useless.”50 Users marked the threshold for failure of alarms much lower than in the case of other technologies whose functionality did not have such high stakes.

Determining when to push the button could pose a problem for the user; one did not want to “cry wolf” or incur criticism for illegitimate or reactionary behavior. One man learned the hard way when he didn’t take a noise seriously in the middle of the night: “‘I suppose there are many nervous people, with no greater cause than I have, who would push that button and have the police here in a jiffy,’” he surmised, and decided to ignore the sound and go back to sleep. Much to his chagrin, he discovered in the morning that burglars had indeed invaded the property successfully.51 The man had worried about inappropriately calling police in the case of a nonemergency; this incident drew attention to the fact that users (and nonusers) interpreted buttons in ways that fit into broader social norms. Yet avoiding the appearance of being “pushy”—forceful despite a lack of force—could come with its own consequences.

Although users often employed buttons to prevent crimes from occurring or emergency situations from spiraling out of control, others co-opted pushes for more nefarious practices. Just as a finger on the button could send a signal that would bring law enforcement officials to one’s door, that same finger could help criminals to elude their captors. Journalists often reported on instances when individuals involved in illegal activities pressed a button to signal their compatriots in an act of warning when police were nearby. This strategy most commonly behooved illegal gambling rings, poker games, and pool halls, where large groups would congregate and need to disperse quickly.52 A “sentinel” stationed outside on the lookout could provide instantaneous warning with a push no different than the one used to ring an electric doorbell, or he could step on a button embedded in the floor that would trigger an emergency red light, taking advantage of the fact that one could conceal buttons.53 Although it often took police a long time to break up these groups because of this technology, in other cases, the button acted as evidence in officials’ pursuit of a criminal. According to a report in the Boston Daily Globe, for example, a night patrolman was caught leaving his shift and entering a bank when he accidentally set off an electric bell “connected by wire with a press button fastened on top of the table in the adjoining room,” thereby leading to his capture.54

The notion of pushing in panic situations took root in the automobile industry, too, with anxiety over how to manage other drivers and pedestrians in a changing transportation landscape that put drivers at a greater remove from their surroundings. Initially, automobile signals resembled bulb horns used on bicycles. These rubber bulbs could cramp one’s hand after a time, and they required removing a hand from steering, thus potentially causing accidents. Additionally, after such great overuse, many motorists began to ignore the sound produced by bulb horns altogether.55 To this end, the electric button alternative could afford a welcome relief. Drivers adopted push-button horns slowly because—as with many electrical appliances—they were often distrusted by the public.56 These electrical accessories also varied widely in price, with high-end arrangements costing around $35 and less expensive ones in the range of $3 to $5.

By the 1910s, electric horn button products came in a dizzying array of shapes and sizes with a diverse catalog of sounds that inventors designed to make warnings quickly at hand (or at foot).57 Manufacturers built horn buttons to withstand weather and repeated use, constructing them from rubber or hard black telephone composition.58 Despite the expense of horn outfits, purchasing only a horn button cost approximately 40 to 50 cents. One could acquire this item from nearly any electrical or automobile supplies catalog and even attach a button to an existing bulb horn.59 Automobile horns actuated by push button existed as part of a broader landscape of sounds common in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many of which took on a disciplinary character—a kind of enforcement—meant to convey alerts, warnings, or danger.

Different driving contexts required appropriately matched sounds: advertisers suggested a “powerful warning signal” for city driving and a contrasting “courteous signal” for country and touring trips.60 Automobile owners could choose the horn that offered the right sound, ranging from the Klaxon , which promised to make enough noise to “awake the dead” (known still today for its infamous “ah-oo-gah” sound), to the SirenO, which provided a “short, quick blast,” to the SwarZ Electreed, which was “neither offensive nor musical, just a business-like warning.”61 Although these insistent calls of warning were lauded for their ability to penetrate surrounding noises (e.g., city traffic) in cases of imminent danger, electric horns received highly unfavorable reviews, as did many electric bells used in hotels and homes, from the population at large for the sound pollution they caused.62 Indeed, the “gentle citizen with tender nerves” would complain about “raucous, ear-splitting” noise.63 In part, one could trace offensive sounds to drivers as well as enterprising children who would seek out the horn with “unflinching” fingers for amusement, much in the vein of amusing doorbell presses or tricky streetcar pushes.64 Little boys were often blamed for manipulating automobile horns in their caretakers’ absences, with observations that “the horn is ‘honked’ by every small boy that passes by” and “at nearly all ages boys ... take especial delight in sounding the horns of unoccupied vehicles,” which was “extremely annoying.”65 Youthful hands within easy reach of buttons often victimized ears with fingers that ruled the sounds of the day. Most of the time, pedestrians, passersby, and even motorists abhorred horns for the noises they made; although the hand gesture of pushing might have seemed more polite, these sounds were perceived as rude. Still, the cacophony could be handy, for instance, when an offensively loud device with its “piercing shriek,” wired to a car door, warded off burglars trying to steal automobile parts.66

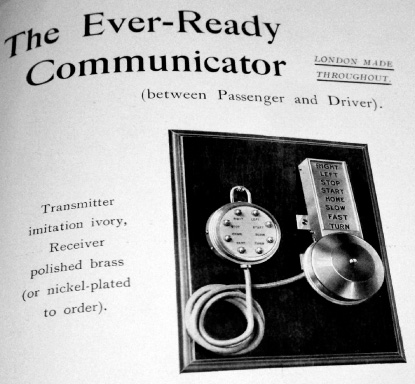

Alongside signaling to drivers and pedestrians outside of the automobile, push buttons also served numerous functions for facilitating communication between passenger and driver or chauffeur. As was the case with mansions, hotels, or railway cars, only a small segment of the population had access to these devices, and they served to manage relationships (whether successfully or unsuccessfully) between employer and employee; as with push-button managers pushing to command their staff or housewives pushing to order around their servants, buttons functioned as a way of both maintaining and overcoming distance. Electrical products such as the Ever-Ready “Communicator” promised this benefit. Made without metal parts so as not to “soil the gloves and hands of the passengers,” the Communicator worked like an annunciator; on pressing a button in the rear of the car, a word with the rider’s need would appear on the dashboard (e.g., “left,” “right,” “slow down,” “go faster”).67 The passenger could also ring a bell to gain the driver’s attention (see figure 7.4).68 Electric vehicles appointed with silk curtains, cigar lighters, mirrors, and so on for wealthy passengers also commonly featured a version of the “Communicator” or a speaking tube, as did cabs or broughams to facilitate conversation with the driver.69 Although these kinds of devices did not achieve widespread uptake, their invention speaks to concerns about communicating within private spaces while disseminating orders in traditionally hierarchical relationships. This act of digital command functioned to enforce such relationships so that the pusher need not lift more than a finger.

Figure 7.4 The “Communicator” managed relations between chauffeur and passenger by facilitating communication across distance.

Source: Ever-Ready Corporation, Eveready Motor Accessories, 1910. Image courtesy of the Warshaw Collection of Business Americana—Electricity, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

An uptick in drivers and sales of automobiles in the twentieth century mandated thinking about modes of signaling while on the road, particularly when drivers and passengers—or drivers and other drivers—were increasingly separated from one another.

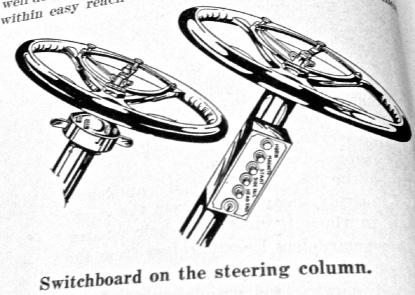

Inventors and manufacturers of automobiles argued for the necessity of push-button operation as a luxury feature as well as a safety tool in terms of accessibility. In similar fashion to the arguments made for push-button lights to counteract unwieldy, groping movements in darkness, automobile manufacturers depicted a hand in control and freed from its former exasperations—no “fumbling” of fingers and no “searching” (see figure 7.5).70 Early electric horns commonly featured a quite simple push-button design; a push button embedded in a steering wheel would trigger an electric bell mounted to the underside of the car’s carriage. Pressing the button with the thumb of one’s left hand would engage the signal.71 Although some automobiles would feature a horn in this central location, motorists might choose to set up additional buttons at various places in the car to manipulate the signal.72 No standardization existed for where horn buttons should be located across all automobile dashboards; this variability sometimes made it more difficult for drivers to acclimate to a new vehicle and understand its controls.73 Some advocated for “centralized control” as a necessary feature, but wondered, “Will it come? Yes, if the public says so. And then it will be the quest of ‘button, button, who’s got the button’?”74 Advocates for placing horns right in the center of the steering wheel looked to the public to generate demand, and they appealed to drivers’ safety concerns and need for instant accessibility.

Figure 7.5 Buttons embedded in steering wheels or their columns were designed to make control always at hand and to become a seamless part of the driving experience.

Source: S. P. McMinn, “The Car of 1915: Some of the More Important Changes Ushered in with the New Year,” Scientific American (January 2, 1915). Image courtesy of the Warshaw Collection of Business Americana—Electricity, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

An ad for a Ford accessory horn set the scene for what dangers could befall the driver without an easily touchable and reachable horn:

Thick traffic—a child trying to cross in front of the machine—driver can’t reach the horn button in time—and then! Too late! Why isn’t the Ford horn button placed where it is on other cars—in the center of the steering wheel—where it can be easily, handily reached? This is the device that puts it there!75

Likewise calling on safety and focusing on reachability, the popular Tuto horn spawned a smaller version called the “Tutoette,” which featured thumb control from the steering wheel so that it was “always at instant command and without reaching for it.”76 Advertisements that focused on push-button control for horns emphasized their dependability, quick response, and effortless touch. They told potential purchasers, “One touch of the finger does it,” with only slight finger pressure required for easy manipulation of a button that would always be “on.”77 The quality of reachability figured importantly in these configurations because they equated excessive (or any) reaching with danger.

In the case of manual gear shifting, too, formerly the driver was “obliged to take her eyes from the road, release her hand from the steering wheel and grope vainly for a shifting lever, upon the movement of which her very life may depend.”78 However, with a Vulcan Electric Gear Shift, the Cutler-Hammer Manufacturing Co. promised that groping would be relegated to a practice of the past. It didn’t matter what kind of hand pushed the button, and economy of that hand’s movement—no lost motion—meant that push-button activities were meant to fade into the background of driving experiences.79 These products and the ads that accompanied them proposed that buttons did not warrant a great deal of the driver’s attention, and they did not require frequent repair or adjustment.80 Manufacturers sold buttons as a seamless part of the driving experience, with the features of digital command as a cornerstone of their appeals. Numerous accessories to automobiles reimagined hand modalities, moving from a model of manual strength to the gentle touch at the tips of the extremities.81

Looking at inventors’ patents related to push-button automobiles reveals a similar pattern of concern for handiness, reachability, and avoidance of the dangers of groping. Inventors often cited gloves as a barrier to easy button-pushing practices, noting that “it is practically impossible or at least inconvenient to operate the button without removing the glove or mitten from the hand.”82 Designs to remedy this problem made a button larger and more visible so that it “cannot be missed when it is looked for, or felt for, as is more usually the case.”83 Additionally, inventions made buttons increasingly movable so that fingers could strike them from any angle or direction.84 In the case of automobile horns, a desirable button would respond to “pressure from any direction on the top or sides ... so that the chauffeur can use his elbow, as well as his fingers, to sound the horn.”85 How hands (and other body parts) would push buttons fit importantly into creating new push-button products, as did the question of drivers’ attention to the road and the extent to which they needed to see before they pushed. Indeed, “with many of the old type of buttons, the operator always has to take time to look at the button,” Ray H. Manson (1919) observed in his patent for a horn operated entirely by touch.86 Concerns about driver distraction were routinely cited in patent applications, and a widespread belief indicated that touching could take the place of seeing to make the driving experience safer.87 Beyond automobiles, too, push buttons were viewed as indispensable tools of safety because of their accessibility, such as emergency buttons on factory floors.88

As prognosticators looked to the future of automobiles, they imagined digital command with closely grouped controls. Writers for the Electric Railway Journal enthused that on learning about recent advances in automobile technology, “We no longer saw an electric car platform cluttered with a controller, brakes, door and step levers, sander rods, gong pedals, circuit-breaker handles and all the other impedimenta that are accepted necessities of the present-day car.”89 Rather, “What we saw in their place was a neat little benchboard on which were buttons or keys with names indicating the several devices, and an attractive young lady seated in a comfortable chair playing on these keys as on an organ!” Describing a cockpit-esque dashboard made for bodily comfort and convenience—with an attractive female operator—this ideal of digital command prioritized both reachability and simplicity.

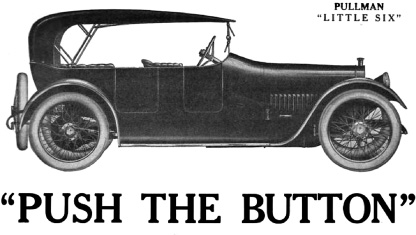

Likewise, manufacturers further emphasized how buttons would eliminate needless gestures and reduce many hand movements to a single-touch operation. Pullman boasted of its “Little Six” vehicle, “It has been aptly termed the ‘Push-the-Button Car.’ ... We do not ask the driver to shift gears, start the motor, or do anything but ‘Push The Button.’” Referring to the Kodak slogan, the ad concluded, “The gasoline and electric current will do the rest.”90 The company idealized how buttons could reduce a series of manual gestures to one button-pushing finger, delegating the “rest” to the car. To push a button in this context meant not to do anything at all, an appealing notion for individuals intent on eliminating bodily effort from technical experiences. Fetishizing the finger (usually the pointer finger or thumb) served a vital function of reimaging hands that could delegate their labor to others and to machines (see figure 7.6).

Figure 7.6 An advertisement for Pullman’s “Little Six” vehicle emphasized button pushing as the only skill needed to operate the vehicle.

Source: “Pullman ‘Little Six,’” Motor World 39 (April 15, 1914): 63. Image courtesy of University of Michigan Library via Google Books.

This common depiction of an extended finger was repeated across industry promotions, symbolizing the forcelessness of the digital commander’s movements in conjunction with a powerful machine. Advertisers had determined that buttons were “good for” almost any situation, but in practice users seemed to accept them more as panic buttons than as conveyors of messages in day-to-day labor relations. Where the urgent nature of communication via button could justify a forceful demand for presence—a push for immediate attention—in other circumstances, these pushes represented an injurious imbalance of effort between pusher and pushed.