BYRON’S LIFE STORY

BYRON’S LIFE STORY

As a child, Byron had the nickname le diable boiteux, or “the limping devil”—a reference to his clubfoot. His affliction made him deeply self-conscious, but it didn’t slow him down: He refused to wear a brace and still managed to excel at sports as a boy. His character at the time was described as “courageous, quarrelsome, resentful, sensitive, abounding in animal spirits … full of mischief.”

As a child, Byron had the nickname le diable boiteux, or “the limping devil”—a reference to his clubfoot. His affliction made him deeply self-conscious, but it didn’t slow him down: He refused to wear a brace and still managed to excel at sports as a boy. His character at the time was described as “courageous, quarrelsome, resentful, sensitive, abounding in animal spirits … full of mischief.”

For a university education, Byron headed to Trinity College, Cambridge, where his free spirit chafed under the strict Anglican morality. While a student, Byron achieved some notoriety with his first book of poetry, Fugitive Pieces, but the book was not a financial success, and he left university in crippling debt. In spite of his dire financial straits, he embarked on his “Grand Tour” of Europe, a trans-European trip taken by noble youth of the time. Unfortunately, due to financial difficulties and the Napoleonic wars, the trip had to be rerouted and he missed some of the traditional Grand Tour destinations in Europe. Byron instead explored Greece, Albania, and Constantinople.

Upon returning to England, Byron delivered a number of passionate speeches as a member of the House of Lords, branding himself an extremist in his views on religion and social reform. He soon left England again, this time for Italy, by way of Switzerland. In Switzerland he spent time with author Mary Shelley and her family. Both authors shared and compared their work, and one of the products of this time in Geneva became Shelley’s famous Frankenstein.

When he settled in Italy, Byron published the first two cantos of Don Juan, an epic poem, in 1819. Don Juan recounts the exploits of a famous womanizer, and it remains Byron’s best-known and most admired work. Fellow author Goethe called it “a work of boundless genius,” but it was also criticized for its apparent immortality.

When he settled in Italy, Byron published the first two cantos of Don Juan, an epic poem, in 1819. Don Juan recounts the exploits of a famous womanizer, and it remains Byron’s best-known and most admired work. Fellow author Goethe called it “a work of boundless genius,” but it was also criticized for its apparent immortality.

In addition to producing great literature, Byron was also a political activist. He aided in the Italian fight for independence from Austria, and later followed his political convictions to Greece as well, which was then in the midst of a massive struggle for independence. In an effort to aid the Greek resistance, Byron chartered the sailing ship Hercules and began giving orders to a rebel army to attack a Turkish-held fortress. Sadly he developed a feverish sickness and died before the mission could begin.

THE STORY OF HIS SEX LIFE

THE STORY OF HIS SEX LIFE

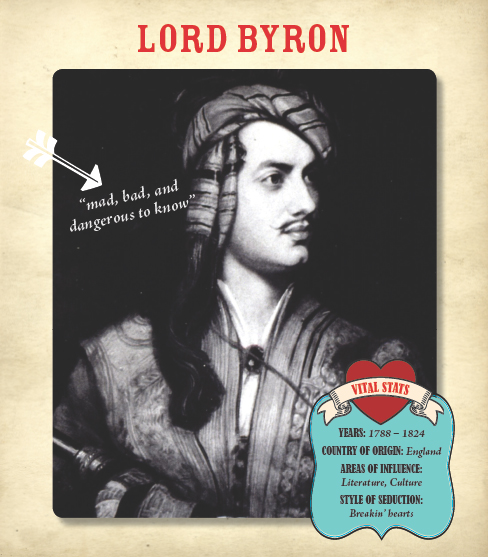

Byron married Annabella Milbanke in 1815 but carried on numerous extramarital affairs over the course of his lifetime with both men and women. In addition to the child he had with his wife (Ada Lovelace, who grew up to be a famous mathematician; see page 36), he fathered at least one other illegitimate child, and possibly many more. Furthermore, he is thought to have had an incestuous relationship with his half-sister, Augusta, who may have borne him another child. Most famous of his many paramours, however, was Lady Caroline Lamb, who notoriously called him “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.”

WHY HE MATTERS

WHY HE MATTERS

Byron was the foremost literary celebrity of his day and remains widely read even now, but his influence was nowhere more important than in overcoming—or at least lessening—many cultural taboos of the time. Throughout his hugely successful career as a poet, Byron consistently shocked Victorian audiences with his frank and graphic portrayal of sexuality and sexual acts. The writer offered no apologies and only occasionally censored his own pieces for the sake of profit.

BYRON’S ANIMAL ADDICTION

Lord Byron was a lifelong animal lover, and wherever he went he had animals in tow. It sounds charming, but you can imagine how it could present some problems for those who had the misfortune to host the notorious Lord. Here is just a sampling of some of his most famous companions.

A Tamed Bear. While attending Trinity College, Byron adopted a tamed bear and housed it in his dormitory room.

A Tamed Bear. While attending Trinity College, Byron adopted a tamed bear and housed it in his dormitory room.

A Wolf Dog. When he left university and moved to Newstead Abbey (tamed bear in tow), he found a new companion as well: a dog that was part wolf.

A Wolf Dog. When he left university and moved to Newstead Abbey (tamed bear in tow), he found a new companion as well: a dog that was part wolf.

Geese. It’s said that when Lord Byron learned that the three geese strapped in his coach to Genoa were to be slaughtered and eaten, he covertly rescued them. Uncharacteristically, however, he did not wish to keep the wild birds, and instead gave them as a gift to his banker.

Geese. It’s said that when Lord Byron learned that the three geese strapped in his coach to Genoa were to be slaughtered and eaten, he covertly rescued them. Uncharacteristically, however, he did not wish to keep the wild birds, and instead gave them as a gift to his banker.

A Menagerie. While embarking on an affair with Theresa Guiccioli, Byron kept ten horses, eight dogs, three monkeys, five cats, an eagle, a crow, and a falcon at his villa.

A Menagerie. While embarking on an affair with Theresa Guiccioli, Byron kept ten horses, eight dogs, three monkeys, five cats, an eagle, a crow, and a falcon at his villa.

As recently as 1969, a memorial for Lord Byron was placed in the Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Aside from being one of the most prolific poets of the romantic period, Byron created the figure of the Byronic hero—a trope still used in poetry as a symbol of someone of high class but little tact, irresponsible, self-destructive, and yet possessed of an unceasing zest for life and love.

BEST FEATURE: His unique personality.

BEST FEATURE: His unique personality.

Lord Byron is sometimes considered the first public celebrity. As a result of his fame, Byron pushed the limits—even wearing curling papers (the Victorian equivalent of hot rollers) to bed each night to style his hair. In addition to pushing the limits of fashion, he also played with the boundaries of art and sexuality, challenging his contemporaries’ views of what was acceptable.

HEAT FACTOR: Byron was a man of means who knew his way around the thesaurus … and the bedroom.

HEAT FACTOR: Byron was a man of means who knew his way around the thesaurus … and the bedroom.

Lord Byron was the archetype of the sexy, tortured poet. His adventurous sexuality, paired with serious athleticism in the physical prime of his early life, made him an attractive figure, in spite of his philandering. On the upside of his Casanova lifestyle, Byron’s embrace of many forms of sexual expression (minus the alleged incest) was ahead of its time and helped to set the stage for more progressive thinking on sexuality in the years to come.

Lord Byron was the archetype of the sexy, tortured poet. His adventurous sexuality, paired with serious athleticism in the physical prime of his early life, made him an attractive figure, in spite of his philandering. On the upside of his Casanova lifestyle, Byron’s embrace of many forms of sexual expression (minus the alleged incest) was ahead of its time and helped to set the stage for more progressive thinking on sexuality in the years to come.

QUOTABLES

“Friendship is Love without his wings!”

Lord Byron, Hours of Idleness

“My great comfort is, that the temporary celebrity I have wrung from the world has been in the very teeth of all opinions and prejudices. I have flattered no ruling powers; I have never concealed a single thought that tempted me.”

Lord Byron, letter to Thomas Moore, 1814

“The world is rid of Lord Byron, but the deadly slime of his touch still remains.”

John Constable, letter to the Rev. John Fisher, 1824