HEMINGWAY’S LIFE STORY

HEMINGWAY’S LIFE STORY

Hemingway was born and raised in the Chicago suburbs. His father and mother, a physician and a musician, respectively, were fairly well-off, and by age four, the toddler alternated his time between playing the cello, hunting, and fishing. As a teenager, however, Hemingway ditched the classical instrument and doubled-down on the wilderness portion of the curriculum, and nature eventually became an important theme in his work.

Hemingway was born and raised in the Chicago suburbs. His father and mother, a physician and a musician, respectively, were fairly well-off, and by age four, the toddler alternated his time between playing the cello, hunting, and fishing. As a teenager, however, Hemingway ditched the classical instrument and doubled-down on the wilderness portion of the curriculum, and nature eventually became an important theme in his work.

While still a student, Hemingway began to flex his literary muscles as a journalist for his high school newspaper and for the school yearbook, Tabula. With those accomplishments— however modest—on his résumé, he was able to move and find work at the Kansas City Star, whose style guide played a major role in developing his voice as a writer: “Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English.”

In 1918, Hemingway left the States for Europe, which was then embroiled in World War I. He served as an ambulance driver and Red Cross volunteer in Italy, where he was wounded while on duty. In return for saving a fellow soldier’s life, young Hemingway received the Italian Silver Medal of Bravery. Yet, not even six months in the hospital could slow him down, as he quickly fell in love with his caretaker, Agnes von Kurowsky. She agreed to marry him but then ran off with a less-vulnerable Italian officer. In all of his ensuing marriages (save the last), Hemingway would wind up abandoning his wife before she had a chance to abandon him. In a way, his advice to overcome writer’s block paralleled his strategy for love: “The best way is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next. If you do that every day … you will never be stuck.”

While recovering at home from his war injuries, Hemingway began writing stories of loneliness— the isolation of the forests, the solitariness of soldiers in battle—and with that, his fiction career commenced. He also accepted a position at the Toronto Star in order to gain a real-world income, and eventually worked as a foreign correspondent in France, where he moved with his first wife, the redheaded Hadley Richardson. While reveling in both the grit and the glory of 1920s Paris, he secured a drinking partner in James Joyce, a proofreader in Ezra Pound, and a mentor in Gertrude Stein. After drinking deeply from the cup of life in Europe, the young couple moved back to Toronto in 1923, where Hadley gave birth to their first son while Ernest published his first book, a collection of stories called Three Stories and Ten Poems. Hemingway yearned for the quicker tempo of a big European city, however, and the couple soon returned to Paris—where they were then divorced.

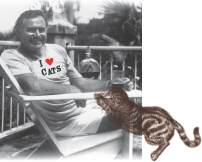

Hemingway’s wanderlust got a little out of hand during his second marriage to Pauline Pfeiffer. Together they went from Key West to Wyoming, Kansas City (where his second son was born), Cuba, East Africa, and finally the Caribbean, where he went on a self-guided boating tour. Soon after, he began covering the Spanish Civil War and World War II while simultaneously working on the draft of For Whom the Bell Tolls. It was around this time that he also began cultivating a cat lady–esque existence in Cuba (complete with dozens of actual cats, of course).

In 1954, Hemingway was falsely reported dead after surviving two plane crashes while on safari in Africa. His receipt of the Nobel Prize for literature in October of the same year was tainted, in his opinion, by the proximity of the two events. In a foreboding acceptance speech, Hemingway wrote of life as an author: “For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.” The curmudgeon spent much of the rest of his life bedridden with various alcohol-related ailments, such as liver disease and hypertension. In 1961, Hemingway followed in the tragic footsteps of his father, brother, and sister by committing suicide.

In 1954, Hemingway was falsely reported dead after surviving two plane crashes while on safari in Africa. His receipt of the Nobel Prize for literature in October of the same year was tainted, in his opinion, by the proximity of the two events. In a foreboding acceptance speech, Hemingway wrote of life as an author: “For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.” The curmudgeon spent much of the rest of his life bedridden with various alcohol-related ailments, such as liver disease and hypertension. In 1961, Hemingway followed in the tragic footsteps of his father, brother, and sister by committing suicide.

THE STORY OF HIS SEX LIFE

THE STORY OF HIS SEX LIFE

A tryst in the City of Lights wouldn’t be complete without a little romantic drama. Hemingway’s time in Paris certainly had that, as his literary star was rising just as his marriage was falling apart— due in part to an affair with Vogue writer Pauline Pfeiffer.

In the style of every reality TV show there ever was, he later in life proposed to his third wife, Mary, while still married to his second wife, Martha. Hemingway wouldn’t stand for panned reviews of both his latest relationship and his latest work, so—always an author first—he composed the draft of The Old Man and the Sea in a marathon eight weeks.

WHY HE MATTERS

WHY HE MATTERS

Though his reputation for boozing sometimes overshadows the legacy of his literature, Ernest Hemingway was a Lost Generation (a phrase he borrowed from Gertrude Stein for one of the two epigraphs in The Sun Also Rises) novelist perhaps most notable for the high school English favorites For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea. Hemingway was seriously rolling in literary swag, winning the Pulitzer for fiction in 1953, then the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954. Indubitably in the “bad boy” category, the writer was a rugged veteran of two World Wars and three ex-wives, and he had a lifelong obsession with bullfighting. His wartime prose humanized the soldiers of World Wars I and II and is still read in classrooms today to better understand the turbulent history of this period.

BEST FEATURE: His manliness.

BEST FEATURE: His manliness.

It may have been exaggerated in his work, but the overwhelming manliness of Hemingway’s pursuits—fighting men, fighting bulls, catching fish, chasing submarines, writing about wars and brawls and brutality—did nothing to detract from the appeal of his square-jawed masculinity. He had his problems, his cats, his insecurities, and his exes, but he also had a real thirst for life and for thrilling experiences. For a good time, call Ernest Hemingway. Just don’t marry him.

HEAT FACTOR: Too hot for words—or for extraneous adjectives, anyway.

HEAT FACTOR: Too hot for words—or for extraneous adjectives, anyway.

He was a bombastic, insecure, bipolar man—but man, did he live a full life. A date with Ernest Hemingway was a date you wouldn’t soon forget, but a marriage to the literary icon was much more problematic, as a rule. Still, in terms of sheer masculine handsomeness, he’s hard to beat.

IN HIS OWN WORDS

“I love sleep. My life has the tendency to fall apart when I’m awake, you know?”

“There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

“I drink to make other people more interesting.”

“There’s no one thing that’s true. It’s all true.”