9

Reorganizing the Financial Statements

Traditional financial statements—the income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows—do not promote easy insights into operating performance and value. They simply aren't organized that way. The balance sheet mixes together operating assets, nonoperating assets, and sources of financing. The income statement similarly combines operating profits, interest expense, the amortization of acquired intangible assets, and other nonoperating items.

To prepare the financial statements for analyzing economic performance, you need to reorganize the items on the balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows into three categories: operating items, nonoperating items, and sources of financing. This often requires searching through the notes to separate accounts that aggregate operating and nonoperating items. Although this task seems mundane, it is crucial for avoiding the common traps of double-counting, omitting cash flows, and hiding leverage that artificially boosts reported performance.

Since the process of reorganizing the financial statements is complex, this chapter proceeds in three steps. Step 1 presents a simple example demonstrating how to build invested capital, net operating profit less adjusted taxes (NOPLAT), and free cash flow (FCF). The second step applies this method to the financial statements for UPS and FedEx, with comments on some of the intricacies of implementation. The final step provides a brief summary of advanced analytical topics, including how to adjust for operating leases, pensions, capitalized expenses, and restructuring charges. An in-depth analysis of each of these topics can be found in Part Three.

Reorganizing the Accounting Statements: Key Concepts

To calculate return on invested capital (ROIC) and FCF, it is necessary to reorganize the balance sheet to create invested capital and likewise reorganize the income statement to create NOPLAT. Invested capital represents the total investor capital required to fund operations, without regard to how the capital is financed. NOPLAT represents the total after-tax operating profit (generated by the company's invested capital) that is available to all investors.

ROIC and FCF are both derived from NOPLAT and invested capital. ROIC is defined as:

and free cash flow is defined as:

By combining noncash operating expenses, such as depreciation, with investment in invested capital, it is also possible to express FCF as:

Invested Capital: Key Concepts

To build an economic balance sheet that separates a company's operating assets from its nonoperating assets and financial structure, we start with the traditional balance sheet. The accounting balance sheet is bound by the most fundamental rule of accounting:

The traditional balance sheet equation, however, mixes operating liabilities and sources of financing on the right side of the equation.

Assume a company has only operating assets (OA) such as receivables, inventory, and property, plant, and equipment (PP&E); operating liabilities (OL) such as accounts payable and accrued salaries; interest-bearing debt (D); and equity (E). Using this more explicit breakdown of assets, liabilities, and equity leads to an expanded version of the balance sheet relationship:

Moving operating liabilities to the left side of the equation leads to invested capital:

With this new equation, we have rearranged the balance sheet to more accurately reflect capital used for operations and the financing provided by investors to fund those operations. Note how invested capital can be calculated using either the operating method (that is, operating assets minus operating liabilities) or the financing method (debt plus equity).

For many companies, the previous equation is too simple. Assets consist of not only operating assets, but also nonoperating assets (NOA), such as marketable securities, prepaid pension assets, nonconsolidated subsidiaries, and other long-term investments. Liabilities consist of not only operating liabilities and interest-bearing debt, but also debt equivalents (DE), such as unfunded retirement liabilities, and equity equivalents (EE), such as deferred taxes and income-smoothing provisions (we explain equivalents in detail later in the chapter). We can expand our original balance sheet equation to show these:

Rearranging leads to total funds invested:

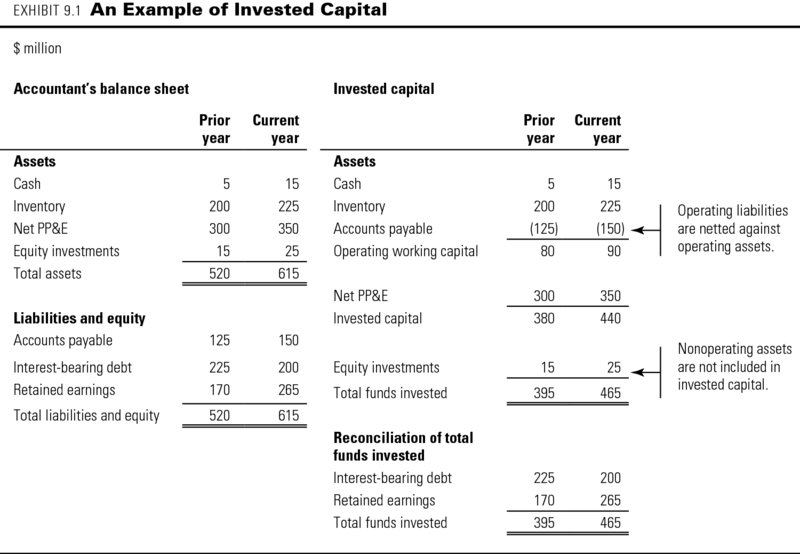

From an investing perspective, total funds invested equals invested capital plus nonoperating assets. From the financing perspective, total funds invested equals debt and its equivalents plus equity and its equivalents. Exhibit 9.1 rearranges the balance sheet into invested capital for a simple hypothetical company with only a few line items. Note how the amount of total funds invested is identical regardless of the method used.

Net Operating Profit Less Adjusted Taxes: Key Concepts

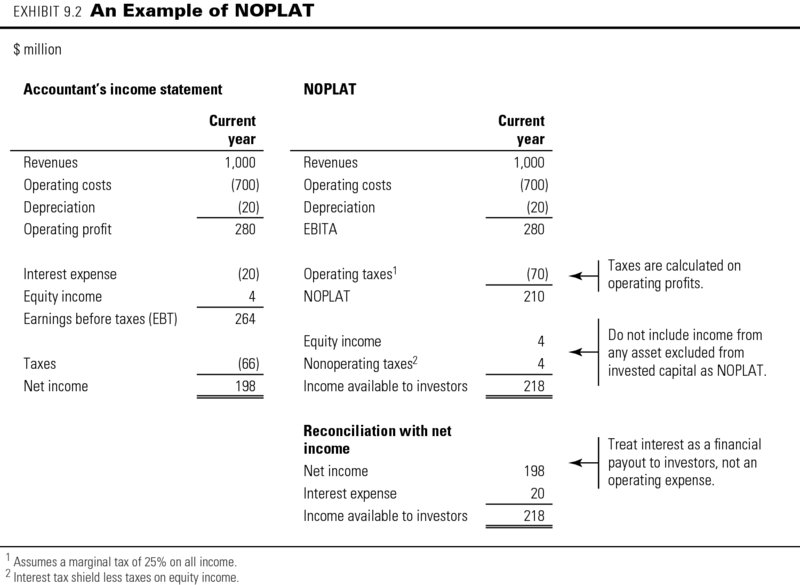

NOPLAT is the after-tax profit generated from core operations, excluding any income from nonoperating assets or financing expenses, such as interest. Whereas net income is the profit available to equity holders only, NOPLAT is the profit available to all investors, including providers of debt, equity, and any other types of financing. It is critical to define NOPLAT consistently with your definition of invested capital and to include only those profits generated by invested capital. To calculate NOPLAT, we reorganize the accounting income statement (see Exhibit 9.2) in three ways. First, interest is not subtracted from operating profit, because interest is a payment to the company's investors, not an operating expense. By reclassifying interest as a financing item, we make NOPLAT independent of the company's capital structure.

Second, when calculating after-tax operating profit, exclude any nonoperating income generated from assets that were excluded from invested capital. Mistakenly including nonoperating income in NOPLAT without including the associated assets in invested capital will lead to an inconsistent definition of ROIC (the numerator and denominator will include unrelated elements).

Finally, since reported taxes are calculated after interest and nonoperating income, they are a function of nonoperating items and capital structure. Keeping NOPLAT focused solely on operations requires that the effects of interest expense and nonoperating income also be removed from taxes. To calculate operating taxes, start with reported taxes, add back the tax shield from interest expense, and remove the taxes paid on nonoperating income. The resulting operating taxes should equal the hypothetical taxes that would be reported by an all-equity, pure operating company. Nonoperating taxes, the difference between operating taxes and reported taxes, are not included in NOPLAT, but instead as part of income available to investors.

Free Cash Flow: Key Concepts

To value a company's operations, we discount projected free cash flow at a company's weighted average cost of capital. Free cash flow is the after-tax cash flow available to all investors: debt holders and equity holders. Unlike “cash flow from operations” reported in a company's annual report, free cash flow is independent of financing and nonoperating items. It can be thought of as the after-tax cash flow—as if the company held only core operating assets and financed the business entirely with equity. Free cash flow is defined as:

As shown in Exhibit 9.3, free cash flow excludes nonoperating flows and items related to capital structure. Unlike the accounting cash flow statement, the free cash flow statement starts with NOPLAT (instead of net income). As discussed earlier, NOPLAT excludes nonoperating income and interest expense. Instead, interest is treated as a financing cash flow.

Net investments in nonoperating assets and the gains, losses, and income associated with these nonoperating assets are not included in free cash flow. Instead, nonoperating cash flows should be valued separately. Combining free cash flow and nonoperating cash flow leads to cash flow available to investors. As is true with total funds invested and NOPLAT, cash flow available to investors can be calculated using two methodologies: one starts from where the cash flow is generated, and the other starts with the recipients of the cash flow. Although the two methods seem redundant, checking that both give the same result can help avoid line item omissions and classification pitfalls.

Reorganizing the Accounting Statements: In Practice

Reorganizing the statements can be difficult, even for the savviest analyst. Which items are operating assets? Which are nonoperating? Which items should be treated as debt? As equity?

In the following pages, we examine today's complex accounting through an examination of the global shipping giant United Parcel Service (UPS), and comparison with FedEx, a direct competitor. UPS struggled during the financial crisis of 2007–2009 but has since improved its performance to pre-crisis levels. FedEx also witnessed declines during the financial crisis but has not yet matched UPS's return on invested capital. This chapter sets the stage for analyzing the two companies by reorganizing their financial statements into operating, nonoperating, and financial items.

Invested Capital: In Practice

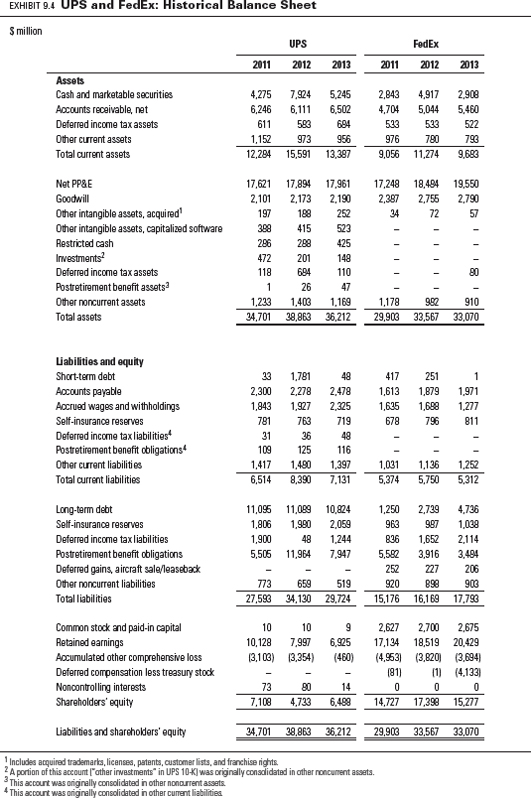

To compute invested capital, we reorganize the company's balance sheet. Exhibit 9.4 presents expanded balance sheets for UPS and FedEx. The reorganized versions presented are more detailed than the balance sheets reported in each company's annual reports, because we have searched the annual report's footnotes for information that enables the disaggregation of any accounts that mix together operating and nonoperating items. For instance, UPS's 2013 notes reveal that the company aggregates investment in partnerships and postretirement benefits within the “other assets” line item.1 Since “other assets” combines operating and nonoperating items, the balance sheet in its original form would be unusable for valuation purposes.

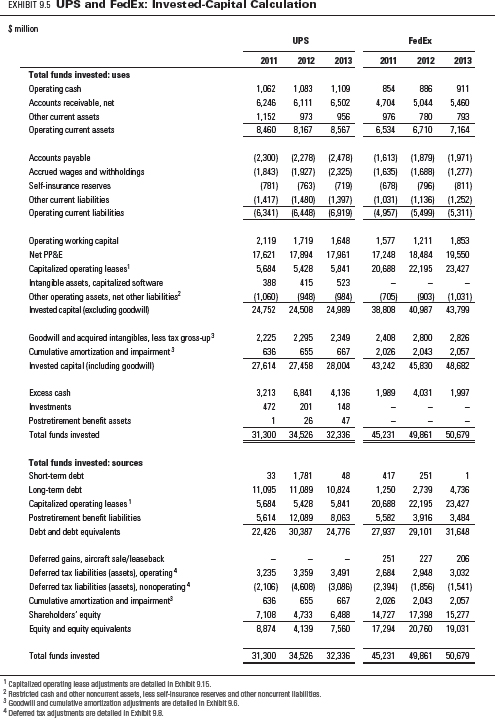

Invested capital sums operating working capital (current operating assets minus current operating liabilities); fixed assets (net property, plant, and equipment); net other long-term operating assets (net of long-term operating liabilities); and, when appropriate, intangible assets (goodwill, acquired intangibles, and capitalized software). Exhibit 9.5 demonstrates this line-by-line aggregation for UPS and FedEx. In the following subsections, we examine each element in detail.

Operating working capital

Operating working capital equals operating current assets minus operating current liabilities. Operating current assets comprise all current assets necessary for the operation of the business, including working cash balances, trade accounts receivable, inventory, and prepaid expenses. Specifically excluded are excess cash and marketable securities—that is, cash greater than the operating needs of the business. Excess cash generally represents temporary imbalances in the company's cash position. We discuss this later in this section.2

Operating current liabilities include those liabilities that are related to the ongoing operations of the firm. The most common operating liabilities are those related to suppliers (accounts payable), employees (accrued salaries), customers (as either prepayments or deferred revenue), and the government (income taxes payable).3 If a liability is deemed operating rather than financial, it should be netted from operating assets to determine invested capital and consequently incorporated into free cash flow. Interest-bearing liabilities are nonoperating and should not be netted from operating assets, but rather valued separately.

Some argue that operating liabilities, such as accounts payable, are a form of financing and should be treated no differently than debt. However, this would lead to an inconsistent definition of NOPLAT and invested capital. NOPLAT is the income available to both debt and equity holders, so when you are determining ROIC, you should divide NOPLAT by debt plus equity. Although a supplier may charge customers implicit interest for the right to pay in 30 days, the charge is an indistinguishable part of the price, and hence an indistinguishable part of the cost of goods sold. Since cost of goods sold is subtracted from revenue to determine NOPLAT, operating liabilities must be subtracted from operating assets to determine invested capital. A theoretical but cumbersome alternative would be to treat accounts payable as debt and adjust NOPLAT for the implicit interest cost.

Net property, plant, equipment, and other capitalized investments

The book value of net property, plant, and equipment (e.g., production equipment and facilities) is always included in operating assets. Situations that require using the market value or replacement cost are discussed in Chapter 10.

Some companies, such as UPS, have significant investments in software. Under certain restrictions, these investments can be capitalized on the balance sheet rather than immediately expensed. Although it is labeled as an intangible asset, treat capitalized software no differently than property and equipment; treat amortization as if it were depreciation; and treat investments in capitalized software as if they were capital expenditures.4 Only internally generated intangible assets, however, should be treated in this manner. Acquired intangibles require special care and are discussed separately.

Other operating assets, net liabilities

If other long-term assets and liabilities are small—and not detailed by the company—we typically assume they are operating. To determine net other long-term operating assets, subtract other long-term liabilities from other long-term assets. This figure should be included as part of invested capital. If, however, other long-term assets and liabilities are relatively large, you will need to disaggregate each account into its operating and nonoperating components before you can calculate net other long-term operating assets.

For instance, a relatively large other long-term assets account might include nonoperating items such as deferred tax assets, prepaid pension assets, nonconsolidated subsidiaries, and other equity investments. Nonoperating items should not be included in invested capital.5 Long-term liabilities might similarly include operating and nonoperating items. Operating liabilities are liabilities that result directly from an ongoing operating activity. For instance, UPS warranties some services beyond one year, collecting customer funds today but recognizing the revenue (and resulting income) only gradually over the warranty period. However, most long-term liabilities are not operating liabilities, but rather what we deem debt and equity equivalents. These include unfunded pension liabilities, unfunded postretirement medical costs, restructuring reserves, and deferred taxes.

Where can you find the breakdown of other assets and other liabilities? In some cases, companies provide a table in the footnotes. Most of the time, however, you must work through the footnotes, note by note, searching for items aggregated within other assets and liabilities. For instance, in 2013 UPS aggregated an investment partnership within other assets. This was reported solely in the 2013 footnote titled “Cash and Investments.” In 2012 and 2013, UPS aggregated an $896 million liability related to withdrawing from a pension plan within other noncurrent liabilities. Although the jump in other noncurrent liabilities signaled the issue, only an investigation of the footnotes pointed to the cause.

Goodwill and acquired intangibles

In Chapter 10, return on invested capital is analyzed both with and without goodwill and acquired intangibles. ROIC with goodwill and acquired intangibles measures a company's ability to create value after paying acquisition premiums. ROIC without goodwill and acquired intangibles measures the competitiveness of the underlying business. For instance, Dutch brewer Heineken6 has a better ROIC with goodwill and acquired intangibles than Danish brewer Carlsberg, but this difference is attributable to premiums Carlsberg paid to acquire breweries, not inferior operating performance. When ROIC is computed without goodwill and acquired intangibles, Carlsberg's operating performance exceeds that of Heineken. To prepare for both analyses, compute invested capital with and without goodwill and acquired intangibles.

To evaluate goodwill and acquired intangibles properly, you need to make two adjustments. First, subtract deferred tax liabilities related to the amortization of acquired intangibles. Why? When amortization is not tax deductible, the accountants create a deferred tax liability at the time of the acquisition that is drawn down over the amortization period (since reported taxes will be lower than actual taxes). To counterbalance the liability, acquired intangibles are artificially increased by a corresponding amount, even though no cash was laid out. For UPS, acquired intangibles are small, so the reduction is minor. For companies with significant acquired intangibles—for example, Coca-Cola—the adjustment can be substantial.

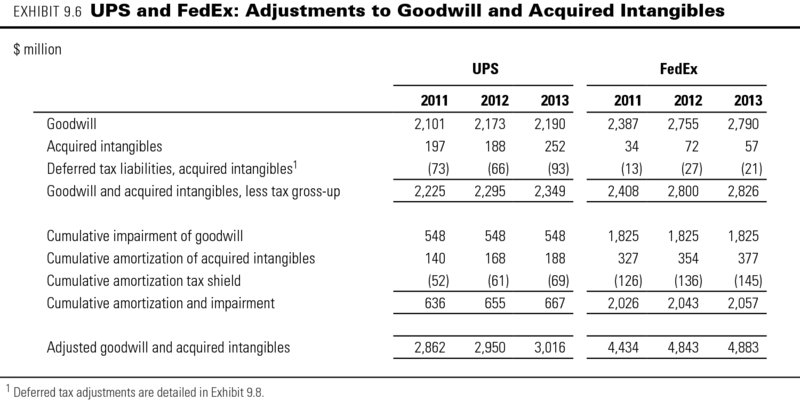

Second, add back cumulative amortization and impairment. Unlike other fixed assets, goodwill and acquired intangibles do not wear out, nor are they replaceable. Therefore, you need to adjust reported goodwill and acquired intangibles upward to recapture historical amortization and impairments.7 (To maintain consistency, do not deduct amortization and impairments of goodwill and acquired intangibles from revenues to determine NOPLAT.) In Exhibit 9.6, amortization and impairments dating back to 2003 are added back to UPS and FedEx's recorded goodwill and acquired intangibles. For example, in 2007, FedEx wrote down approximately $900 million in goodwill and acquired intangibles when it converted the acquired brand name Kinko's to FedEx Office. Failing to add back this impairment would have caused a large artificial jump in return on invested capital in 2007. The money spent on the acquisition is real and needs to be accounted for, even when the investment fails to work.

Computing Total Funds Invested

Invested capital represents the capital necessary to operate a company's core business. In addition to invested capital, companies can also own nonoperating assets. Nonoperating assets include excess cash and marketable securities, receivables from financial subsidiaries (e.g., credit card receivables), nonconsolidated subsidiaries, overfunded pension assets, and tax loss carryforwards. Summing invested capital and nonoperating assets leads to total funds invested.

Excess cash and marketable securities

Do not include excess cash in invested capital. By its definition, excess cash is unnecessary for core operations. Rather than mix excess cash with core operations, analyze and value excess cash separately. Given its liquidity and low risk, excess cash will earn very small returns. Failing to separate excess cash from core operations will incorrectly depress the company's apparent ROIC.

Companies do not disclose how much cash they deem necessary for operations. Nor does the accounting definition of cash versus marketable securities distinguish working cash from excess cash. Based on past analysis, companies with the smallest cash balances held cash just below 2 percent of sales. If this is a good proxy for working cash, any cash above 2 percent should be considered excess.8 In 2013, UPS held $5.2 billion in cash and marketable securities on $55.4 billion in revenue. At 2 percent of revenue, operating cash equals just $1.1 billion. The remaining cash of $4.1 billion is treated as excess. Exhibit 9.5 separates operating cash from excess cash. Note how excess cash is not computed as part of invested capital with goodwill, but rather treated as a nonoperating asset.

Financial subsidiaries

Some companies, including IBM, Siemens, and Caterpillar, have financing subsidiaries that finance customer purchases. Because these subsidiaries charge interest on financing for purchases, they resemble banks. Since bank economics are quite different from those of manufacturing companies, you should separate line items related to the financial subsidiary from the line items for the manufacturing business. Then evaluate the return on capital for each type of business separately. Otherwise, significant distortions of performance will make a meaningful comparison with competitors impossible. For more on how to analyze and assess financial subsidiaries, see Chapter 17.

Nonconsolidated subsidiaries and equity investments

Nonconsolidated subsidiaries and equity investments should be measured and valued separately from invested capital. When a company owns a minority stake in another company, it will record the investment as a single line item on the balance sheet and will not record the individual assets owned by the subsidiary. On the income statement, only income from the subsidiary will be recorded on the parent's income statement, not the subsidiary's revenues or costs. Since only income and not revenue is recorded, including nonconsolidated subsidiaries as part of operations will distort margins and capital turnover. Therefore, we recommend separating nonconsolidated subsidiaries from invested capital and analyzing and valuing nonconsolidated subsidiaries separately from core operations.

Overfunded pension assets

If a company runs a defined-benefit pension plan for its employees, it must fund the plan each year. And if a company funds its plan faster than its pension expenses dictate or assets grow faster than expected, under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Accounting/Financial Reporting Standards (IAS/IFRS) the company can recognize a portion of the excess assets on the balance sheet. Pension assets are considered a nonoperating asset and not part of invested capital. Their value is important to the equity holder, so they will be valued later, but separately from core operations. Chapter 20 examines pension assets in detail.

Tax loss carryforwards

Unless they are small and grow consistently with revenue, do not include tax loss carryforwards—also known as net operating losses (NOLs)—as part of invested capital. Depending on the type of carryforward, it will be valued either separately or as part of operating cash taxes. The treatment of deferred taxes is discussed in more detail in a subsequent subsection.

Other nonoperating assets

Other nonoperating assets, such as derivatives, excess real estate, and discontinued operations, also should be excluded from invested capital. For UPS, derivatives were disclosed in the footnotes but are immaterial, so no adjustments were made to the balance sheet accounts. For more on derivatives, see the comprehensive case of Heineken presented in Chapter 24.

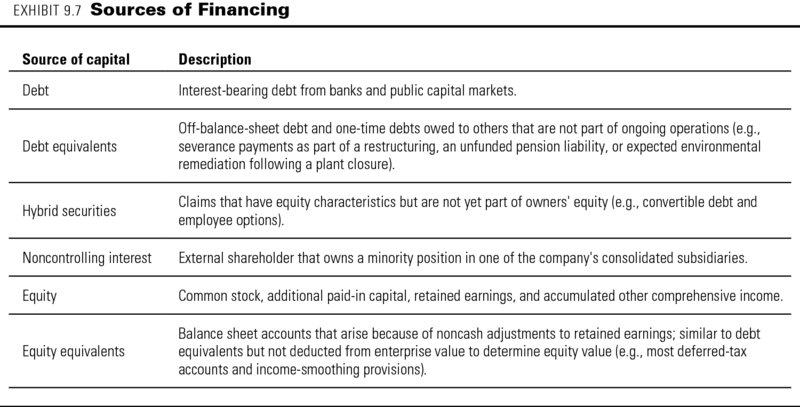

Reconciling Total Funds Invested

Total funds invested can be calculated as invested capital plus nonoperating assets, as in the previous section, or as the sum of debt, equity, and their equivalents. The totals produced by the two approaches should reconcile. A summary of sources of financing appears in Exhibit 9.7. We next examine each of these sources of capital contributing to total funds invested.

Debt

Debt includes any short-term or long-term interest-bearing liability. Short-term debt includes commercial paper, notes payable, and the current portion of long-term debt. Long-term debt includes fixed debt, floating debt, and convertible debt with maturities of more than a year.

Debt equivalents such as retirement liabilities and restructuring reserves

If a company's defined-benefit plan is underfunded, it must recognize the underfunding as a liability. The amount of underfunding is not an operating liability. Rather, treat unfunded pension liabilities and unfunded postretirement medical liabilities as a debt equivalent (and treat the net interest expense associated with these liabilities as nonoperating). It is as if the company must borrow money to fund the plan. As an example, UPS announced in 2012 that it would withdraw from the multiemployer New England Teamsters & Trucking Industry Pension Fund. To be released from its obligations to the fund, UPS promised to pay $43 million per year for 50 years. This fixed repayment promise, an obligation with seniority to equity claims, is really no different from traditional debt.

Other debt equivalents, such as reserves for plant decommissioning and restructuring reserves, are discussed in Chapter 19.

Hybrid securities

Hybrid securities are claims against enterprise value that have characteristics similar to equity but are not part of common equity. The three most common hybrid securities are convertible debt, preferred stock, and employee options. The claims should be treated similarly to debt equivalents and valued separately.

Noncontrolling interest

A noncontrolling interest (formerly called a minority interest) occurs when a third party owns some percentage of one of the company's consolidated subsidiaries. If a noncontrolling interest exists, treat the balance sheet amount as an equity equivalent. Treat the earnings attributable to any noncontrolling interest as a financing cash flow similar to dividends.

Equity

Equity includes original investor funds, such as common stock and additional paid-in capital, as well as investor funds reinvested into the company, such as retained earnings and accumulated other comprehensive income (OCI). In the United States, accumulated OCI consists primarily of currency adjustments, aggregate unrealized gains and losses from liquid assets whose value has changed but that have not yet been sold, and pension plan fluctuations within a certain band. IFRS also includes accumulated OCI within shareholders' equity but reports each reserve separately. Any stock repurchased and held in the treasury should be deducted from total equity.

Equity equivalents such as deferred taxes

Equity equivalents are balance sheet accounts that arise because of noncash adjustments to income and retained earnings. Equity equivalents are similar to debt equivalents; they differ only in that they are not deducted from enterprise value to determine equity value.

The most common equity equivalent, deferred taxes, arises from differences in how businesses and the government account for taxes. For instance, the government typically uses accelerated depreciation to determine a company's taxes, whereas the accounting statements are prepared using straight-line depreciation. This leads to cash taxes that are lower than reported taxes during the early years of an asset's life. For growing companies, this difference will cause reported taxes consistently to overstate the company's actual tax payments. To avoid this bias, use cash-based (versus accrual) taxes to determine NOPLAT. Since reported taxes will now match cash taxes, the deferred-tax account—in this case related to accelerated depreciation—is no longer necessary. This is why the original deferred-tax account is referred to as an equity equivalent. It represents the adjustment to retained earnings that would be made if the company reported cash taxes to investors.

Not every deferred-tax account should be incorporated into cash taxes, only deferred-tax assets (DTAs) and deferred-tax liabilities (DTLs) associated with ongoing operations.9 Nonoperating tax liabilities, such as deferred taxes related to pensions, should instead be valued as part of the corresponding liability. To compute operating cash taxes accurately, separate deferred taxes into the following three categories, and treat them as recommended:

- Operating deferred-tax assets and liabilities: Deferred-tax liabilities (net of deferred-tax assets) related to the ongoing operation of the business should be treated as equity equivalents. For example, UPS carries deferred-tax assets related to vacation pay and accelerated depreciation, among others. They will be used to compute operating cash taxes in the next section.

- Nonoperating deferred-tax assets and liabilities: Treat deferred-tax liabilities (net of deferred-tax assets) as an equity equivalent. Nonoperating deferred taxes are deferred taxes related to nonoperating assets (such as pensions), debt (such as implicit interest), or debt equivalents (such as restructuring expenses).

- Intangible assets, gross-up: As discussed earlier, deferred-tax liabilities related to amortization of acquired intangibles should be netted against acquired intangibles.

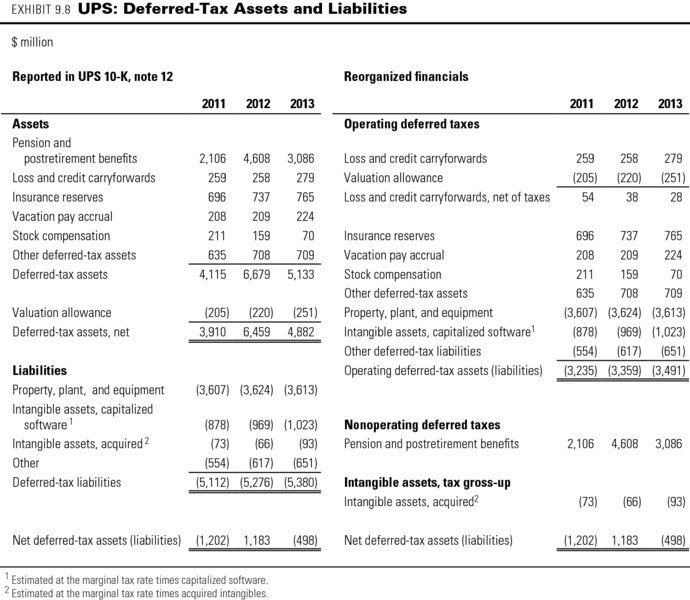

Exhibit 9.8 uses the UPS deferred-tax footnote to disaggregate deferred taxes into operating and nonoperating. To determine operating deferred taxes, start with operating related and ongoing deferred tax assets like loss and credit carryforwards,10 self-insurance reserves, vacation pay, and stock compensation. From these accounts, subtract taxes related to accelerated depreciation and capitalized software. Operating deferred-tax liabilities totaled $3,491 million in 2013.

Operating DTLs are treated as an equity equivalent in Exhibit 9.5, and the change in operating DTLs will be the basis for computing cash taxes later in this chapter. Nonoperating DTLs are also treated as an equity equivalent in Exhibit 9.5. Only DTLs related to acquired intangibles are netted against their corresponding account.

Calculating NOPLAT

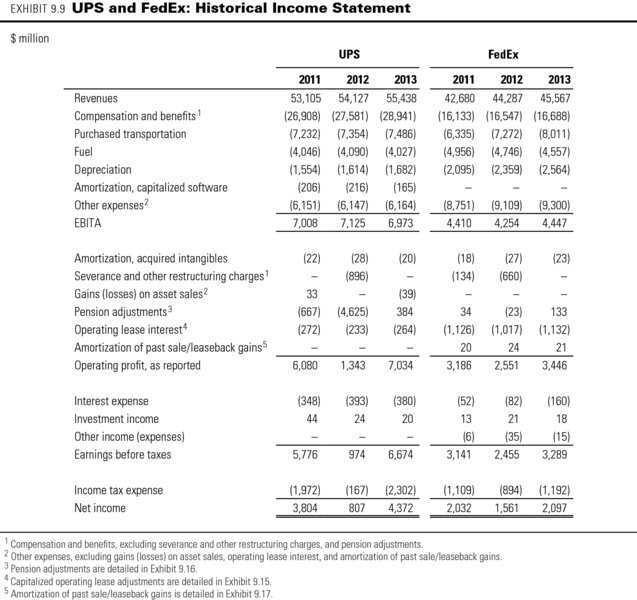

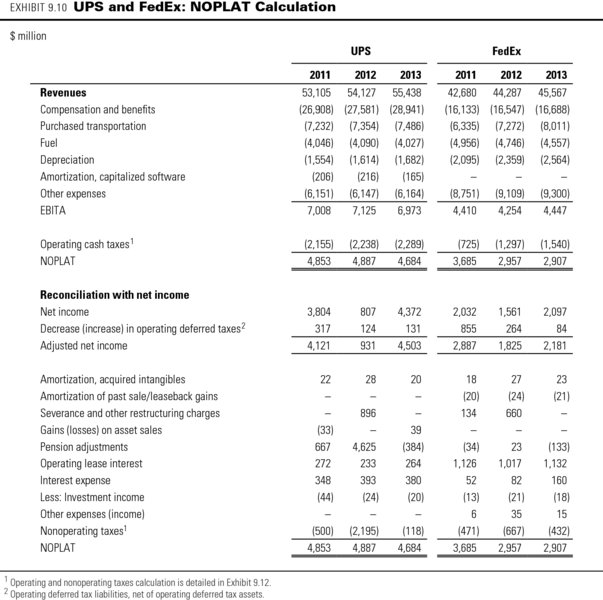

To determine NOPLAT for UPS and FedEx, we turn to their respective income statements (see Exhibit 9.9) and convert each income statement into NOPLAT (see Exhibit 9.10).

Net operating profit (NOP or EBITA)

NOPLAT starts with earnings before interest, taxes, and amortization (EBITA) of acquired intangibles, which equals revenue less operating expenses (e.g., cost of goods sold, selling costs, general and administrative costs, depreciation).

Why use EBITA and not EBITDA? When a company purchases a physical asset such as equipment, it capitalizes the asset on the balance sheet and depreciates the asset over its lifetime. Since the asset wears out over time, depreciation is included as an operating expense when determining NOPLAT as a rough proxy for the deterioration of that asset.

Why use EBITA and not EBIT? After all, the same argument could be made for the amortization of acquired intangibles: they, too, have fixed lives and lose value over time. But the accounting for intangibles differs from the accounting for physical assets. Unlike capital expenditures, organic investment in intangibles such as new customer lists and product brands are expensed and not capitalized. Thus, when the acquired intangible loses value and is replaced through additional investment, the reinvestment is already expensed, and the company is penalized twice: once through amortization and a second time through reinvestment. Using EBITA avoids double-counting amortization expense in this way.

Adjustments to EBITA

In many companies, nonoperating income expenses are embedded within EBITA. To ensure that EBITA arises solely from operations, dig through the notes to weed out nonoperating items. The most common nonoperating items are related to pensions, embedded interest expenses from operating leases, restructuring charges hidden in the cost of sales, and gains or losses from asset sales.

When a number of adjustments are required, reorganize the income statement prior to creating NOPLAT.11 In Exhibit 9.9, we separate six items that were included in the UPS and FedEx reported operating profit.12 For instance, in 2012, UPS took an $896 million charge to withdraw from the New England plan and another $4,625 million in actuarial losses to revalue its defined benefit pension liability primarily due to lower interest rates.13 Both these charges were incorporated in the compensation and benefits number reported by UPS, causing the number to spike in 2012, and reported operating profit to plummet.14 To best reflect UPS's ongoing compensation and benefits, separate these charges from ongoing activities. This separation, however, will not change the ultimate level of pretax profit or net income. The separation merely makes like-to-like comparison simpler to conduct and better reflects the underlying operating performance of the company.

Adjustments related to pensions and operating leases are briefly addressed at the end of this chapter and in detail in Part Three, which covers advanced valuation issues.

Operating taxes

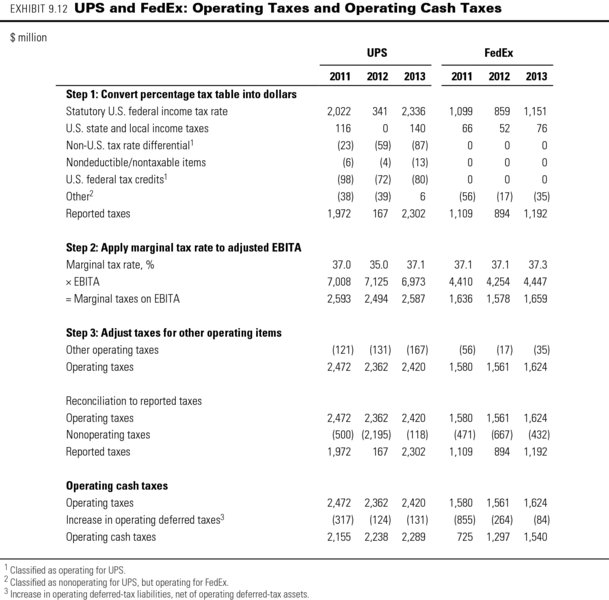

Since nonoperating items also affect reported taxes, taxes must be adjusted to an all-equity operating level. The process for adjusting taxes can be complex. Chapter 18 provides an in-depth explanation of the process we recommend for computing operating cash taxes. To estimate operating taxes, proceed in three steps:

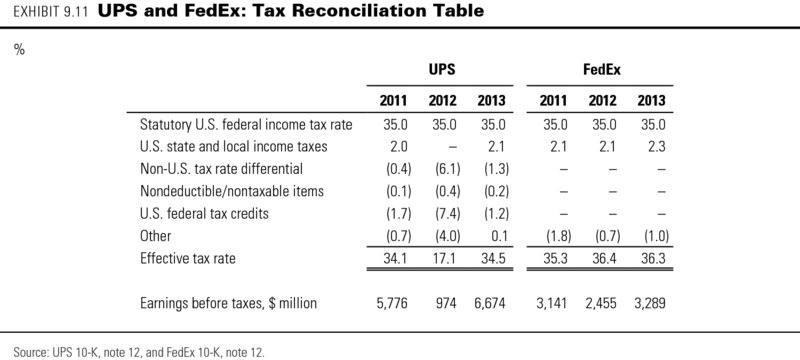

- Search the footnotes for the tax reconciliation table. For tables presented in dollars (or other home currencies), build a second reconciliation table in percents, and vice versa. To convert percents into dollars, multiply by earnings before taxes; to convert dollars into percents, divide by earnings before taxes. Data from both tables are necessary to complete the remaining steps.

- Using the percent-based tax reconciliation table, determine the marginal tax rate. The marginal tax rate equals the government tax rate paid on income (in the United States, companies pay federal and state taxes on income). Multiply the marginal tax rate by adjusted EBITA to determine marginal taxes on EBITA.

- Using the dollar-based tax reconciliation table, adjust operating taxes by other operating items not included in the marginal tax rate. The most common adjustment is related to differences in foreign tax rates.

To demonstrate the three-step process, let's examine the operating tax rate for UPS. Start by converting the reported tax reconciliation table (presented in Exhibit 9.11) into dollars.15 The results of this conversion are presented in the top half of Exhibit 9.12. To convert each line item from percent into dollars, multiply the particular line item by earnings before taxes (for UPS, $6,674 million in 2013). Earnings before taxes are reported on the income statement (see Exhibit 9.9). We use the dollar-denominated table in step 3.

Next, use the percentage-based tax reconciliation table to determine the marginal tax rate. You can use the company's statutory rate plus state or local taxes to calculate a proxy for the marginal rate. In 2013, UPS paid 37.1 percent in taxes: federal (35.0 percent) and state (2.1 percent). Use this marginal rate to compute taxes on adjusted EBITA. In 2013, taxes on adjusted EBITA equaled $2,587 million (37.1 percent times $6,973 million in EBITA).

After computing taxes on adjusted EBITA, search the dollar-based reconciliation table for other operating taxes. For UPS, the two operating taxes paid beyond marginal taxes were foreign-rate differences and U.S. tax credits.16 In 2013, foreign-rate differences lowered taxes by $87 million, and U.S. tax credits lowered the number by an additional $80 million. Therefore, lower taxes on adjusted EBITA by $167 million to determine operating taxes in 2013.17

When adjusting marginal taxes for other operating items, we prefer to use dollar adjustments rather than percentage adjustments. To see why, look at the percentages in Exhibit 9.11 for UPS in 2012. Because of the company's multibillion-dollar pension charge in that year, earnings before taxes were uncharacteristically low, making foreign tax savings and U.S. tax credits appear uncharacteristically large on a percentage basis (6.1 and 7.4 percent, respectively). As a consequence, extrapolating this tax rate for cash flow forecasting would lead to a significant overvaluation.

Reconciliation of reported taxes

To reconcile NOPLAT to net income and free cash flow to cash flow available to investors, it is necessary to compute nonoperating taxes. Nonoperating taxes include taxes paid on nonoperating income, tax shields from interest expense, and other nonoperating taxes from the tax reconciliation table. Determine nonoperating taxes by computing the difference between reported taxes and operating taxes. For instance, UPS had a net $118 million tax shield from nonoperating items in 2013 (see Exhibit 9.12).

Operating cash taxes

We recommend using operating cash taxes actually paid, if possible, rather than accrual-based taxes reported.18 The simplest way to calculate cash taxes is to subtract the increase in operating deferred-tax liabilities (net assets) from operating taxes. Exhibit 9.8 separates UPS's net operating DTLs from its net nonoperating DTLs. UPS's net operating DTLs have been rising steadily over the past few years, so reported taxes slightly overstate actual cash taxes. Subtracting the annual increase (or adding the decrease) in operating deferred taxes gives cash taxes.

In 2013, operating taxes were decreased by $131 million at UPS because operating deferred taxes rose from $3,359 million to $3,491 million, as reported in Exhibit 9.8. Using changes in deferred taxes to compute cash taxes requires special care. As discussed in the section on invested capital, only changes in operating-based deferred taxes are included in cash taxes. Otherwise, changes in deferred taxes might be double-counted: once in NOPLAT and potentially again as part of the corresponding item.19

Similar to other accounts, deferred-tax accounts rise and fall as a result of acquisitions and divestitures. However, only organic increases in deferred taxes should be included in operating cash taxes, not one-time increases resulting from consolidation. For companies involved in multiple mergers and acquisitions, a clean measure of operating cash taxes may be impossible to calculate. When this is the case, use operating taxes without the adjustment for cash.

Reconciliation to Net Income

To ensure that the reorganization is complete, we recommend reconciling net income to NOPLAT (see the lower half of Exhibit 9.10). To reconcile NOPLAT, start with net income, and add back the increase (or subtract the decrease) in operating deferred-tax liabilities. Next, add the expenses (or subtract the income) for any adjustments you make to operating income, such as severance charges, lease interest, and pension adjustments. Next, add any nonoperating charges (or subtract income) reported by the company, such as interest expense and investment income. Finally, subtract nonoperating tax shields computed when determining operating taxes.

Free Cash Flow: In Practice

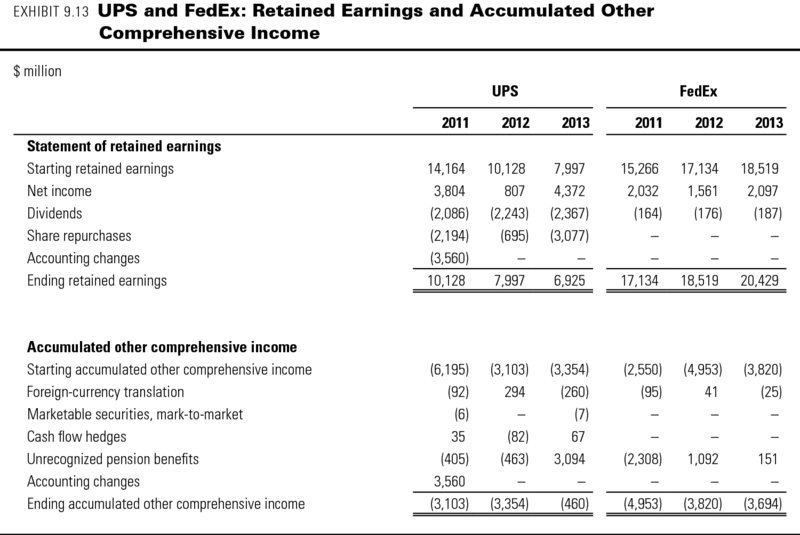

This subsection details how we build free cash flow from the reorganized financial statements. To make further adjustments specific to free cash flow and its reconciliation, the statement of retained earnings and statement of accumulated other comprehensive income are also required. Exhibit 9.13 reports these for UPS and FedEx. Free cash flow is defined as:

Exhibit 9.14 builds the free cash flow calculation and reconciles free cash flow to cash flow available to investors for both UPS and FedEx. The components of free cash flow are gross cash flow and investments in invested capital. If possible, investments in invested capital should be separated into organic investments and investments made through acquisition.

Gross cash flow

Gross cash flow represents the cash flow generated by the company's operations. It represents the cash available for investment and investor payout without the company having to sell nonoperating assets (e.g., excess cash) or raise additional capital. Gross cash flow has two components:

- NOPLAT: As previously defined, net operating profits less adjusted taxes are the after-tax operating profits available to all investors.

- Noncash operating expenses: Some expenses deducted from revenue to generate NOPLAT are noncash expenses. To convert NOPLAT into cash flow, add back depreciation and amortization.20 Only add back amortization deducted from revenues to compute NOPLAT. For UPS, we add back the amortization of capitalized software, which had been deducted to compute EBITA. Do not add back the amortization from acquired intangibles and impairments to NOPLAT; they were not subtracted in calculating NOPLAT.

Investments in invested capital

To maintain and grow their operations, companies must reinvest a portion of their gross cash flow back into the business. To determine free cash flow, subtract gross investment from gross cash flow. We segment gross investment into five primary areas:

- Change in operating working capital: Growing a business requires investment in operating cash, inventory, and other components of working capital. Operating working capital excludes nonoperating assets, such as excess cash, and financing items, such as short-term debt and dividends payable.

- Net capital expenditures: Net capital expenditures equal investments in property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), less the book value of any PP&E sold. One way to estimate net capital expenditures is to add the increase in net PP&E to depreciation.21 Do not estimate capital expenditures by taking the change in gross PP&E. Since gross PP&E drops when companies retire assets (which has no cash implications), the change in gross PP&E will often understate the actual amount of capital expenditures.

- Change in capitalized operating leases: To keep the definitions of NOPLAT, invested capital, and free cash flow consistent, include investments in capitalized operating leases in gross investment. Capitalized operating leases are discussed later in the chapter.

- Investment in goodwill and acquired intangibles: For acquired intangible assets, where cumulative amortization has been added back, you can estimate investment by computing the change in net goodwill and acquired intangibles. For intangible assets that are being amortized, use the same method as for determining net capital expenditures (by adding the increase in net intangibles to amortization).

- Change in other long-term operating assets, net of long-term liabilities: Subtract investments in other net operating assets. As with invested capital, do not confuse other long-term operating assets with other long-term nonoperating assets, such as equity investments and excess pension assets. Changes in equity investments need to be evaluated—but should be measured separately.

Since companies translate foreign balance sheets into their home currencies, changes in accounts will capture both true investments (which involve cash) and currency-based restatements (which are merely accounting adjustments and not the flow of cash into or out of the company). Removing the currency effects line item by line item is impossible. But we can partially undo their effect by subtracting the increase in the equity item titled “foreign-currency translation,” which under U.S. GAAP and IFRS is found within the statement of accumulated other comprehensive income.22 By subtracting the increase, we undo the effect of changing exchange rates.

Another effect that contributes to the change in balance sheet accounts is restatements due to acquisitions and divestitures. In some cases, the company will report line-by-line adjustments, enabling the acquisition or divestiture to be separated from the organic change.23

Cash Flow Available to Investors

Although not included in free cash flow, cash flows related to nonoperating assets are valuable in their own right. They must be evaluated and valued separately and then added to free cash flow to give the total cash flow available to investors:

To reconcile free cash flow with total cash flow available to investors, include the following nonoperating cash flows:

- Nonoperating income and expenses: Unless you can net the account against a change in a corresponding asset or liability (because it is noncash), include nonoperating income and expenses in total cash flow available to investors, not in free cash flow.24

- Nonoperating taxes: Include nonoperating taxes in total cash flow available to investors.25

- Cash flow related to excess cash and marketable securities: Subtract the increase (or add the decrease) in excess cash and marketable securities to compute total cash flow available to investors. If the company reports unrecognized gains and losses related to marketable securities in its statement of other comprehensive income, net the gain or loss against the change computed previously.

- Cash flow from other nonoperating assets: Repeat the process used for excess cash and marketable securities for other nonoperating assets. When possible, combine nonoperating income from a particular asset with changes in that nonoperating asset.

Reconciling Cash Flow Available to Investors

Cash flow available to investors should be identical to the company's total financing flow. By modeling cash flow to and from investors, you will catch mistakes otherwise missed. Financial flows include flows related to debt, debt equivalents, and equity:

- Interest expenses: Interest from both traditional debt and operating leases should be treated as a financing flow.

- Debt issues and repayments: The change in debt represents the net borrowing or repayment on all the company's interest-bearing debt, including short-term debt, long-term debt, and capitalized operating leases. All changes in debt should be included in the reconciliation of total funds invested, not in free cash flow.

- Change in debt equivalents: Since accrued pension liabilities and accrued postretirement medical liabilities are considered debt equivalents (see Chapter 20 for more on issues related to pensions and other postretirement benefits), their changes should be treated as a financing flow.26

- Dividends: Dividends include all cash dividends on common and preferred shares. Dividends paid in stock have no cash effects and should be ignored.

- Share issues and repurchases: When new equity is issued or shares are repurchased, four accounts will be affected: common stock, additional paid-in capital, treasury shares, and retained earnings (for shares that are retired). Although different transactions will have varying effects on the individual accounts, only the aggregate matters, not how the individual accounts are affected. Exhibit 9.14 refers to the aggregate change as “Repurchased (issued) shares.”

Advanced Issues

In this section, we summarize a set of the most common advanced topics in reorganizing a company's financial statements, including operating leases, pensions, capitalized research and development (R&D), nonoperating charges, and restructuring reserves. We provide only a brief summary of these topics here, as each one is discussed in depth in the chapters of Part Three, “Advanced Valuation Techniques.”

Operating Leases

When a company leases an asset under certain conditions, it need not record either an asset or a liability. Instead, it records the rental charge as an expense each period and reports future commitments in the notes.27 To compare asset intensity effectively across companies with different leasing policies, include the value of the lease as an operating asset, with a corresponding debt recorded as a financing item. Otherwise, companies that lease assets will appear “capital light” relative to identical companies that purchase the assets.

Companies typically do not disclose the value of their leased assets. Chapter 20 evaluates alternatives for estimating the value of leased assets. Here we describe a common approach: multiply rent expense by an appropriate capitalization factor, based on the cost of debt (kd) and average asset life:28

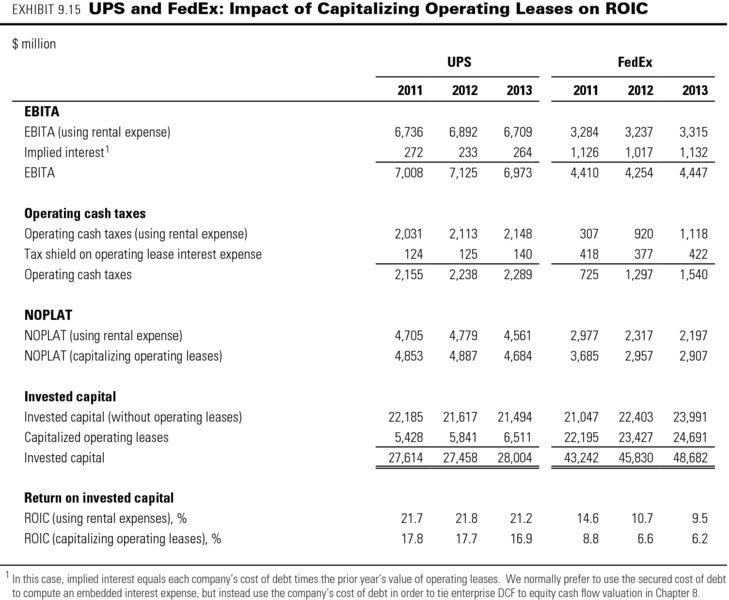

For UPS, if we apply the 5.3 percent cost of its debt (AA-rated debt) and assume an asset life of 20 years, we can convert $575 million in 2013 rental expense to $5.4 billion in 2012 operating leases.29 Exhibit 9.15 presents the resulting adjustment for operating leases for UPS and FedEx. When capitalizing operating leases to estimate invested capital, also make sure to eliminate the interest cost embedded in rental expense from operating profits. For UPS in 2013, Exhibit 9.15 shows that $264 million in embedded interest is added back to reported EBITA to compute total EBITA.

Also, operating taxes are adjusted to remove the associated tax shield. This raises both the numerator (NOPLAT) and the denominator (invested capital) of ROIC. For most companies, capitalizing operating leases lowers a company's ROIC. For UPS in 2013, ROIC drops from 21.2 percent to 16.9 percent, and for FedEx, it drops from 9.5 percent to 6.2 percent. The reduction in FedEx's ROIC actually reduces its ROIC below its WACC.

Whether or not you capitalize operating leases will not affect intrinsic value as long as it is incorporated correctly in free cash flow, the cost of capital, and debt equivalents.

Pensions and Other Postretirement Benefits

Following the passage of FASB Statement 158 under U.S. GAAP in 2006, companies now report the present value of pension shortfalls (and excess pension assets) on their balance sheets.30 Since excess pension assets do not generate operating profits, nor do pension shortfalls fund operations, pension accounts should not be included in invested capital. Instead, pension assets should be treated as nonoperating items, and pension shortfalls as a debt equivalent (and both should be valued separately from operations).31 Reporting rules under IFRS (IAS 19) differ slightly in that companies can postpone recognition of their unfunded pension obligations resulting from changes in actuarial assumptions, but only as long as the cumulative unrecognized gain or loss does not exceed 10 percent of the obligations. For companies reporting under IFRS, search the notes for the current value of obligations.

FASB Statement 158 addressed deficiencies concerning pension obligations on U.S. balance sheets, but not on income statements. Pension expense, often embedded in cost of sales, aggregates the benefits given to employees for current work (known as the service cost) and the interest cost associated with pension liabilities, less the expected return on plan assets as well as a portion of the revaluation of pension assets and liabilities due to changes in interest rates and the value of the pension's portfolio of investments. Only the service cost is an operating cost. So operating costs and profits and must be adjusted to exclude any other pension items.

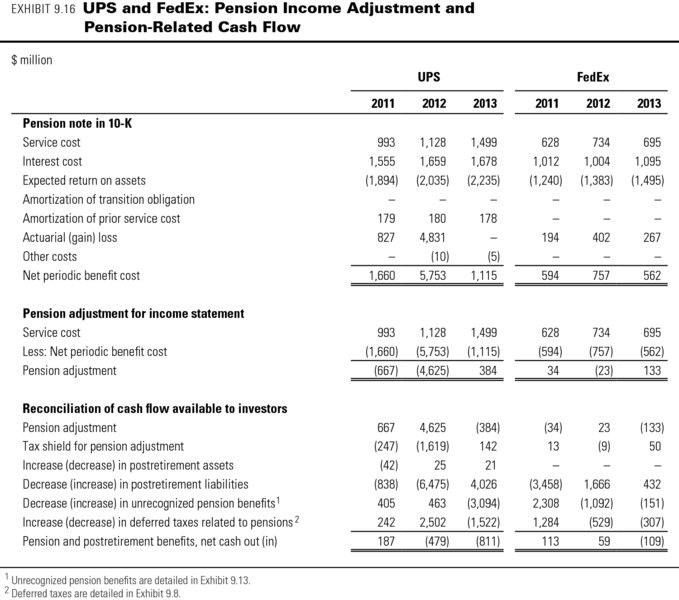

Exhibit 9.16 calculates the pension adjustment using the pension note from the UPS and FedEx 10-Ks. In 2012, the pension expense for UPS was $5,753 million. This expense was embedded in compensation and benefits on UPS's income statement. Yet the majority of this expense was because of actuarial losses due to revaluation of the pension liability as a result of lower interest rates. Therefore, it (and other nonoperating items) should be removed from compensation and benefits, so only the service cost remains. As can be seen in Exhibit 9.16, UPS has generated higher service costs over the last three years, whereas FedEx has been holding the service cost relatively constant.

Chapter 20 provides more detail on how to adjust NOPLAT for pensions and how to factor under- or overfunded pensions into a company's value.

Capitalized Research and Development

In line with the conservative principles of accounting, accountants expense R&D, advertising, and certain other costs in their entirety in the period they are incurred, even when economic benefits resulting from such expenses continue beyond the current reporting period.32 This practice can dramatically understate invested capital and overstate return on capital for some companies. Therefore, you should consider whether it would be effective to capitalize and amortize R&D and other quasi investments in a manner similar to that used for capital expenditures. Equity should be adjusted correspondingly to balance the invested-capital equation.

If you decide to capitalize R&D, the R&D expense must not be deducted from revenue to calculate operating profit. Instead, deduct the amortization associated with past R&D investments, using a reasonable amortization schedule. Since amortization is based on past investments (versus expense, which is based on current outlays), this approach will prevent reductions in R&D from driving short-term improvements in ROIC.

Whether or not you capitalize certain expenses will not affect computed value; it will affect only the timing of ROIC and economic profit. Chapter 21 analyzes the complete valuation process for R&D-intensive companies, including adjustments to free cash flow and value.

Nonoperating Charges and Restructuring Reserves

Provisions are noncash expenses that reflect future costs or expected losses. Companies record provisions by reducing current income and setting up a corresponding reserve as a liability (or deducting the amount from the relevant asset).

For the purpose of analyzing and valuing a company, we categorize provisions into one of four types: ongoing operating provisions, long-term operating provisions, nonoperating restructuring provisions, and provisions created for the purpose of smoothing income (transferring income from one period to another). Based on the characteristics of each provision, adjust the financial statements to reflect the company's true operating performance:

- Ongoing operating provisions: Operating provisions such as product warranties are part of operations. Therefore, deduct the provision from revenue to determine NOPLAT, and deduct the corresponding reserve from net operating assets to determine invested capital.

- Long-term operating provisions: For certain liabilities, such as expected plant decommissioning costs, deduct the operating portion from revenue to determine NOPLAT, and treat the interest portion as nonoperating. Treat the corresponding reserve as a debt equivalent.

- Nonoperating provisions: Provisions, such as restructuring charges related to severance, are nonoperating. Treat the expense as nonoperating and the corresponding reserve as a debt equivalent.

- Income-smoothing provisions: Provisions for the sole purpose of income smoothing should be treated as nonoperating, and their corresponding reserve as an equity equivalent. Since income-smoothing provisions are noncash, they do not affect value.

The process for classifying and properly adjusting for provisions is explained in more detail in Chapter 19.

Other Adjustments

In addition to the most common adjustments for leases, pensions, R&D, and provisions, a company may have other items that require adjustment. These adjustments arise from an uncommon line item on the income statement or balance sheet and, given their rarity, require thoughtful judgment based on the economic principles of this book.

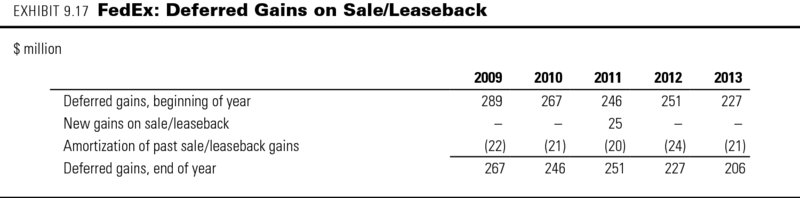

In the case of FedEx, the company recognized $206 million in deferred gains from aircraft sale/leaseback in the liability section of its 2013 balance sheet (see Exhibit 9.4). Should this item be treated as operating? Or perhaps as a debt or equity equivalent? From a valuation perspective, it doesn't matter how to classify the item, as long as it is treated consistently. It will, however, have an impact on our perceptions about return on invested capital and ultimately value creation. A deferred-gains account arises from the gain on selling an aircraft above its book value. If the same plane is then leased back from the buyer, the company cannot recognize the one-time sale as income, but instead must lower the annual rental expense over the life of the contract. Since cash flows in but retained earnings do not rise, a liability is recognized. Accounting standards are concerned about a spike in net income cause by a financial transaction, but we believe a distortion in rental expense is worse, since this lower rental expense is noncash and could distort the perspective of rental expense going forward. Therefore, we choose to undo the transaction.

In order to adjust EBITA, the change in deferred gains must be estimated year by year. These estimates are provided in Exhibit 9.17. To reorganize the balance sheet, we treat the account as an equity equivalent. To reorganize the income statement, we increase the rental expense by the amortization expense and increase nonoperating cash flow by the deferral amount.

Using Judgment with Adjustments

Not every advanced issue will lead to material differences in ROIC, growth, and free cash flow. Before collecting extra data and estimating required unknowns, decide whether the adjustment will further your understanding of a company and its industry. An unnecessarily complex model can sometimes obscure the underlying economics that would be obvious in a simple model. Remember, the goal of financial analysis is to provide a strong context for good financial decision making and robust forecasting, not to create an overly engineered model that handles unimportant adjustments.

Review Questions

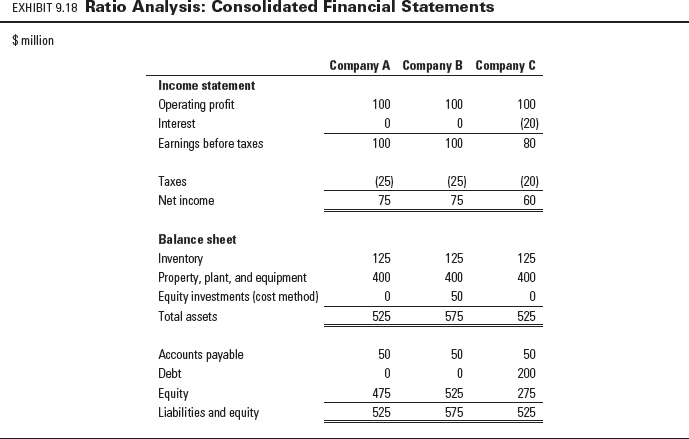

- Exhibit 9.18 presents the income statement and balance sheet for Companies A, B, and C. Compute each company's return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and return on invested capital (ROIC). Based on the three ratios, which company has the best operating performance?

- Why does the return on assets differ between Company A and Company B? Why do companies with equity investments tend to have a lower return on assets than companies with only core operations?

- Why does the return on equity differ between Company A and Company C? Is this difference attributable to operating performance? Which better reflects operating performance, return on assets or return on equity? Why?

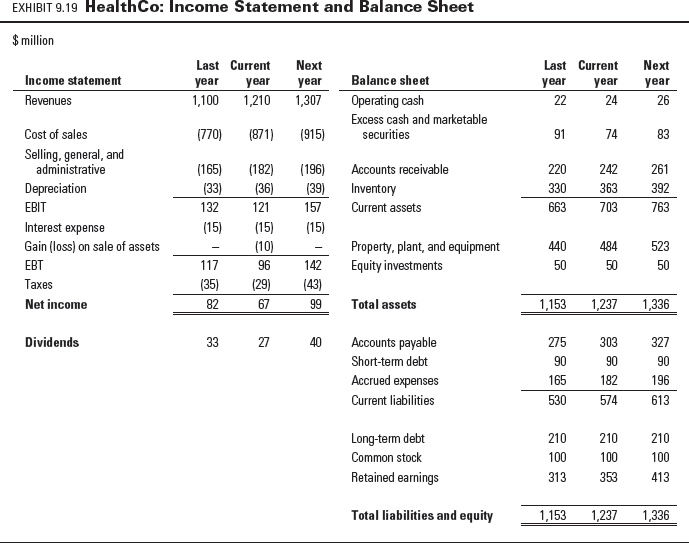

- Exhibit 9.19 presents the income statement and balance sheet for HealthCo, a $600 million health-care company. Compute NOPLAT, average invested capital, and ROIC for the current year and future year. Assume an operating tax rate of 30 percent. If the weighted average cost of capital is 10 percent, is the company creating value? In which year is the firm performing better? Why?

- Using the reorganized financial statements created in Question 4, what is the free cash flow for HealthCo in the current year and next year?

- Many companies hold significant amounts of excess cash, or cash above the amount required for day-to-day operations. What would happen to the ROIC for HealthCo if you included excess cash in its calculation? Why should one exclude excess cash from the calculation?