During the second week of March 1776, General George Washington scored a major victory four months before the Declaration of Independence was signed. He forced the British to leave the city of Boston, where the spark of the Revolution had been struck.

Washington had the heavy cannons that Colonel Henry Knox and his men had valiantly brought from Fort Ticonderoga and placed into position on Dorchester Heights, a piece of hilly land projecting into Boston Harbor. He had fortified the two highest hills, Bunker and Breed’s hills, and bombarded Boston and Boston Harbor with deadly shellfire daily.

The constant American bombardment convinced General Lord William Howe, commander of the British army in Boston, that only an evacuation of the city would save his troops from a military disaster.

In the following days Howe loaded 9,000 soldiers and their supplies on nearly 100 ships and sailed away, apparently headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The remaining Boston residents wildly hailed the American victory, but Washington did not take part. Instead he stared out to sea, wondering about the real destination of Lord Howe and the Royal Navy.

General Washington could not believe Howe was really en route to Halifax. With all the troops, ships, and war material the British had at their command, a movement to Nova Scotia would be a foolish mistake. It seemed to him a more realistic possibility that Howe might risk an attempt to take New York City and its great seaport.

The loss of New York City would be a terrible setback for the Americans. To check such a potential British manuver, Washington rushed troops overland from Boston to New York City. He set his men digging entrenchments from the Battery to the northern tip of Manhattan Island.

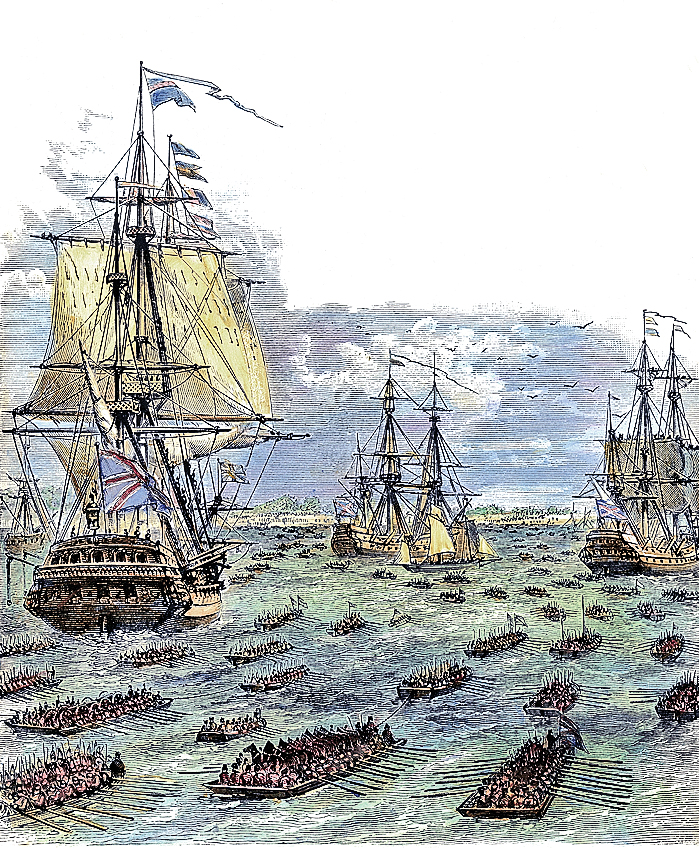

Washington had guessed right. Late in June 1776 the missing British fleet appeared. Lord Howe had more than 100 ships loaded with thousands of British and Hessian troops for an attack on New York City.

And so our story begins. . . .

In August 1776, 20,000 British and Hessian battle-hardened veteran, fully equipped soldiers, under the command of General William Howe, were landed from Royal Navy warships at Gravesend, Long Island.

They attacked and smashed through the American Force stationed on Long Island by Washington to repel any attempt by the British to take New York City. Before the overwhelming English assault, the Colonial army was forced to fall back.

The Continental Army on Long Island retreats from the British and Hessian army’s overpowering attack.

A valiant rearguard delaying action by Delaware and Maryland Continentals, commanded by General William Alexander, Lord Stirling, allowed the retreating Americans enough time to safely reach General Washington’s entrenchments at Brooklyn Heights.

General William Alexander, Lord Stirling. Lord Stirling leading his brave troops in battle against the British and Hessians at Long Island.

The British continued their assault on the Americans. With his back to open water and outnumbered, Washington was in danger of losing his whole army. He ordered his men to gather all the boats they could find and bring them to the East River at dusk. Colonel John Glover’s regiment of Massachusetts fishermen began the enormous task of transporting the American troops at night in a rainstorm to Manhattan Island. It was done so quietly the enemy never knew it was happening. The Americans got away with all their guns, horses, food, and ammunition. Washington took one of the last boats to cross as the foggy dawn lifted, and Howe and the Redcoats found Brooklyn empty.

The British pressed their assault on the Americans, forcing General Washington to retreat from his positions in Manhattan, leaving Fort Washington, on the New York shore, and Fort Lee, on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, to defend themselves against the entire British army and navy. The two forts fell to the Redcoats in quick succession with the loss of large quantities of valuable supplies and 2,600 American officers and men taken prisoners.

Map showing the area of General Washington’s retreat through Long Island, Manhattan, and New Jersey.

Having lost Long Island, Brooklyn, and Manhattan to the enemy, Washington realized General Howe’s next target would be the capital of the Revolution, the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His plan called for reaching Pennsylvania before the British.

On November 12, 1776, Washington led 3,000 men across the Hudson River into New Jersey. General Lord Cornwallis, commanding 10,000 British and Hessian troops, quickly followed, confident they’d catch and destroy the Americans in a short time. Pursuing the rebels relentlessly, they did not allow them to rest.

The weather turned cold and a steady chilling rain fell heavily. Weary, disheartened, sick, poorly equipped, with losses from death and desertion growing daily, Washington’s little army retreated westward across New Jersey. A pursuing British officer wrote, “Many of the Rebels who were killed were without shoes and stockings, and several were observed to have only linen drawers, also in great want of blankets, they must suffer extremely.” They did. But still they struggled onward.

General Washington and his army retreating across New Jersey.

Charles Cornwallis, British general, on November 25, 1776, set off across New Jersey with 10,000 men, determined to catch Washington, he said, as a hunter bags a fox.

Barely keeping his exhausted army ahead of the onrushing British, Washington reached the Delaware River on December 8, 1776. He ordered his troops to seize and destroy all the available boats in the area, except those he needed, then they crossed into Pennsylvania.

With the river between his troops and the British army, Washington halted the retreat and turned his tired, ragged army to face the enemy. Utterly exhausted, freezing, and starved, they awaited the next move by the Redcoats. It started to snow . . . large pieces of ice began to form and float downstream. Fortunately for the Americans, General Howe decided his army would not take the field in the dead of winter. Why bother? According to all reports there would be no rebel army left to face his men come spring.

As 1776, a year of terrible suffering and humiliating defeats, drew to a close, the American cause seemed doomed. The Revolution was crumbling.

Washington’s troops encamped along the Delaware River in 1776. They suffered greatly from lack of winter clothing, food, and shelter.

Thomas Paine, an Englishman who came to America because he believed the colonists’ revolt against English rule to be right.

Thomas Paine, the author of the very popular pamphlet Common Sense, joined Washington’s army as a volunteer. During the retreat across New Jersey he wrote a very powerful essay, “The American Crisis.” It impressed Washington so much he ordered it read before each regiment.

It began: “These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in the crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”

Washington sadly wrote to his brother John, “I think the game is pretty near up. . . . You can form no idea of the perplexity of my situation. No man, I believe, ever had a greater choice of difficulties and less means to extricate himself from them.”

General George Washington, commander in chief of the Continental Army.

Washington and his exhausted army were encamped on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River at a place called McKonkey’s Ferry. At Trenton, on the New Jersey side of the river about nine miles downstream, was Colonel Johann Rall with 1,400 battle-hardened professional Hessian soldiers. Washington pondered over his maps and plans in his headquarters. He looked out on the river with its floating blocks of ice, and the snow-covered hills, and his desolated men gathered around campfires freezing and hungry. He had to do something. The terms of militia enlistments would run out on New Year’s Day, and many of his troops would leave with it. It was late December. He had only a few days open to him. He called his staff together for a council of war to outline his plans. He would take his little army across the river and attack Trenton. The officers were enthusiastic about his plan and decided to cross into New Jersey late on Christmas night when they knew the Hessians would be celebrating and least likely to expect any action by the Americans. So very determined to succeed at their task were these men that the passwords “VICTORY OR DEATH” were chosen for the attack.

“The evening of the 25th I ordered the troops to parade in back of McKonkey’s Ferry, that they might begin to pass as soon as it grew dark, imagining we should be able to throw all over, with the necessary artillary, by 12 o’clock, and easily arrive at Trenton by five in the morning, the distance being about nine miles.

Late in the afternoon on Christmas day the Colonial troops were ordered to move. They made their way down to the riverbank, where, in shivering silence, they started loading the boats. Fifty big artillery horses balked at being led onto the boats. They snorted and stamped on the ground with their hooves, rearing up because they were very nervous. Eighteen cannons, weighing a few hundred pounds each, had to be loaded and tied down so they wouldn’t move once the boats started their journey across the ice-choked river. If a horse made a violent movement or a cannon broke loose from its mooring, the boat, which was overcrowded with troops, would capsize and all on board would perish because of the freezing water.

Colonel Knox had charge of loading the boats. It was a slow, cold job lasting until three o’clock in the morning. Finally they got under way. It was pitch dark. Complete silence was called for. Only the sound of the oars pushing the water and the ice cakes bumping the sides of the boats could be heard. There was no talking or cursing or smoking allowed.

But the quantity of ice made that night

The Delaware River on Christmas night 1776 was a torrent of rushing water blocked with large pieces of ice. The weather was extremely cold, with a biting wind and a driving sleet storm covering everything with a coating of ice. The Hessians, upon viewing the condition of the river, could not imagine anyone daring to cross it on a night such as this. They retired to their quarters to partake in hot meals and drink rum.

Things were different on the Pennsylvania side of the river. Washington ordered all of the “Durham” boats that had been seized and hidden away brought out to the embarkation point. These boats were like oversized canoes, sixty feet long, eight feet wide, shallow draft, pointed at both ends. They were very hard vessels to navigate under the best of conditions, and a perilous means of conveyance for troops and their equipment in the dreadful weather of that night.

A Durham boat

impeded the passage of the boats so much that it was three o’clock before the troops took up their line of march

Colonel Henry Knox, artillery commander of the American army, wrote of the crossing in a letter to his wife on December 28, 1776; “The floating ice on the river made the labor almost incredible. However, perseverance accomplished what at first seemed impossible. About four o’clock the troops were all on the Jersey side.”

To handle the boats in the crossing of the Delaware, Washington once again called on the reliable Colonel John Glover and his regiment of hardy fishermen from Marblehead, New England. These were the same men who had prevented the retreating American army from being destroyed by the British when they ferried the entire Colonial force of 9,000 men, artillery, horses, and heavy equipment aboard flatboats across the East River at night without the British forces’ hearing a thing.

but as I was certain there was no making a retreat without being discovered, and harassed on repassing the river,

Already three hours behind schedule, with nine miles yet to cover over ice-glazed roads, Washington still waited at the landing point until all his men, artillery, horses, and equipment were safely ashore.

Then Washington assembled his troops and began the march to Trenton.

I determined to push on. . . .

An American officer wrote. “It will be a terrible night for the men who have no shoes. Some of them have tied old rags around their feet; others are barefoot, but I have not heard a man complain.” It was said you could follow the trail of the Colonial soldiers’ march toward Trenton by the blood from their bleeding feet on the snow and ice.

Colonel John Glover. Glover’s Marblehead men ferrying the American army across the Delaware River into New Jersey.

This made me dispair of surprising the town, as I well knew we could not reach it before the day was fairly broke,

December 26 dawned peaceful and quiet in the little town of Trenton. The Hessian soldiers and their commander, Colonel Johann Rall, had celebrated Christmas by drinking rum and dancing with the town ladies until early predawn hours and now they slept soundly.

The weather remained horrible, the roads were slick and treacherous; the men and horses constantly fell and the cannon were almost impossible to move.

Halfway to Trenton, Washington ordered his army to split in two. One half, under General John Sullivan, was to proceed on the lower River Road, the other half, commanded by General Nathaniel Greene, was to take the upper Pennington Road. Sullivan reported the rain had soaked his troops’ muskets. Washington ordered General Sullivan to tell his men to use their bayonets. He was resolved to take Trenton.

I formed my detachment into two divisions, one to march by the lower or River Road, the other, by the upper or Pennington Road. As the divisions had nearly the same march, I ordered each of them, immediately upon forcing the out guards to push directly into town, that they might charge the enemy before they had time to form.

General Nathanial Greene, commander of the American troops that approached Trenton on Pennington Road.

The upper division arrived at the enemy’s advance post exactly at eight o’clock, and in three minutes after I found from the fire on the lower road that that division had also got up.

The out guards made but small opposition, though their numbers were small, they behaved very well keeping up a constant fire from behind houses.

At 7:30 a.m. the Americans rapidly approached the outskirts of Trenton. Suddenly an American advance guard ran into a Hessian picket on Pennington Road. Upon seeing the advancing Colonials, he turned and ran for the town shouting, “Der Feind! Heraus! Heraus!” (The enemy! Get up! Get up!)

But it was too late. Musket shots from Sullivan’s division signaled their attack at the lower end of town and Washington was leading Greene’s division as they ran into the upper end of town shooting and shouting their passwords as they ran toward the Hessian enemy; “Victory or Death!”

The Hessians try to form up and battle the Americans but they fail against the Colonials’ onslaught.

We presently saw their main body formed, but from their motions, they seemed undetermined how to act.

The Hessians were slow in rousing after their festive Christmas evening. They rushed into the streets, but still in a daze from their partying, they staggered and tumbled over one another, falling in the wet snow and mud. The Hessians were unable to form ranks.

Colonel Rall was awakened from his drunken sleep by the shouting of his men and the American cannons and musket fire. He unsteadily rushed into the street. He was helped on his horse and, waving his sword, shouted, “Vorwärts! Vorwärts!” (Forward! Forward!) His men formed once and tried to charge into the town.

Being hard pressed by our troops, who had already got possession of part of their artillery, they attempted to file off by a road on their right leading to Princeton, but perceiving their intention I threw a body of troops their way which immediately checked them.

But Colonel Knox rolled his cannons into position and swept the streets with artillery fire. The Hessians were mowed down like wheat.

Finding from our disposition that they were surrounded, and that they must inevitably be cut to pieces if they made any further resistance, they agreed to lay down their arms.

When Rall himself was shot down, mortally wounded, the demoralized Hessians’ resistance ended and they threw down their arms in surrender.

The number that submitted in this manner was 23 Officers and 886 men . . . our loss is very trifling, indeed, only two officers and two privates wounded.

Two hundred Hessians escaped and fled. The Americans took 886 officers and men prisoners of war. Another 106 Hessians were killed or wounded. Washington asked for a list of his casualties and was told four men wounded, two officers and two privates.

A fantastic victory indeed.

Colonel Rall, seriously wounded, is held up by his officers as he surrenders his sword and his army to General Washington.

General John Sullivan, commander of the southern section of Washington’s army that attacked Trenton from River Road.

General Henry Knox, artillery commander for Washington’s army.