An Ancient Oasis: The Canyon's History

People may have been part of Sabino Canyon for longer than saguaros. Twelve thousand years ago, when Paleo-Indian hunters walked into the Southwest at the end of the last Ice Age, it was still a lush landscape of woodlands, marshes, and lakes, teeming with horses and now-extinct species of camel and bison. Large stone spearpoints have been found embedded in mammoth bones near the San Pedro River, seventy-five miles southeast of Sabino Canyon, but archaeologists have turned up scant evidence of the big-game hunters in the Tucson Basin. We do not know for certain if the Southwest's earliest human inhabitants ever camped on the banks of Sabino Creek.

When most of the large mammals vanished, perhaps victims of Paleo-Indian overkill, the people began to subsist on smaller game, supplemented by wild plant foods. During the thousands of years that this Desert Archaic way of life flourished (from roughly 10,000 to 2,000 years ago), the climate warmed and dried, saguaros and paloverdes moved into Sabino Canyon, and the Tucson Basin began to look more like the desert it is today. As a result, mountain canyons like Sabino, with their plentiful food and permanent water, became important to the hunter-gatherers. Archaeologists have often found their flat grindstones (metates), stone points, and other tools at canyon mouths and have tentatively identified a few Desert Archaic artifacts in Lower Sabino Canyon.

Potsherds left by Hohokam Indians

Eventually trade with distant Mesoamerican civilizations brought word of other ways of life to the Desert Archaic people, and they began to plant corn and to live in more permanent settlements. By A.D. 300 the infusion of new ideas had helped to create the sophisticated agriculturists known today as the Hohokam. Over the next thousand years the Tucson Basin's population grew as villages sprang up along the rivers and in the surrounding foothills.

The Hohokam are best remembered today as sedentary farmers, experts in irrigation, but they also kept many of the practices of their Desert Archaic predecessors. They harvested cactus fruits and agave hearts in Sabino Canyon, hunted rabbits and deer there, and used the canyon as a corridor to higher elevations where they gathered acorns and berries. For the first time, human beings began to leave abundant signs of their presence at Sabino Canyon. Today we find rows of stones west of the canyon, remnants of check dams that once caught rainwater and soil to nourish Hohokam crops of corn, squash, beans, and cotton. On the canyon floor there are pits worn in the bedrock and boulders, mortars where the Hohokam ground mesquite beans they gathered in the bosques. And scattered here and there are sherds of Hohokam pots broken hundreds of years ago, some still bearing traces of painted designs.

After A.D. 1200 a small Hohokam settlement near the canyon mouth grew into a large village whose residents farmed the floodplain of Sabino Creek, but within a century the village was abandoned as the population of the entire Tucson Basin shrank. By about 1450 the Hohokam civilization had collapsed. The causes of these momentous changes are a mystery Archaeologists have suggested climatic shifts, invasions, catastrophic disease, or social strife. Today's Tohono Oodham Indians do not know the explanation. "Hohokam" is an English rendering of a phrase in the Oodham language meaning, simply, "all used up."

On the Frontier of New Spain

Archaeologists know little about this areas inhabitants during the next two hundred years. When Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino rode northward into the Tucson Basin at the end of the seventeenth century, he met Piman Indians, possibly descendants of the Hohokam, living in a string of farming villages along the Santa Cruz River, fifteen miles west of Sabino Canyon. Kino paused to name the village of San Cosme de Tucson and the nearby Santa Catalina Mountains. Perhaps the Pimans were still visiting Sabino Canyon to harvest its many resources, but travel east of the river was becoming increasingly dangerous, thanks to some other newcomers to the Southwest: the Apaches.

The Apache Indians had arrived in this area only centuries before. A nomadic people, they mostly traveled peacefully in family groups, harvesting acorns and pinyon nuts in the mountain woodlands, hunting, and raising small crops of beans, squash, and corn. Some Apaches may well have camped in Sabino Canyon. Unfortunately for the Pimans, the Apaches supplemented this simple hunting-and-gathering economy by raiding their more sedentary neighbors.

Thimble Peak, Sabino Canyon's most prominent landmark, was known as Rock Peak in the first half of the twentieth century.

CYPRESS CANYON

The most basic question about Sabino Canyon's history is also the most puzzling: How did the canyon get its name? No one knows, but there has been no shortage of speculation.

Folk history tells us that the canyon was named after a wealthy, influential cattleman named Sabino Otero, who is said to have owned a ranch at the canyon mouth in the late nineteenth century. This popular story is absolutely true, but of another Sabino Canyon in the Baboquivari Mountains, nearly seventy miles to the southwest.

Because the Spanish word sabino is sometimes used as an adjective roughly equivalent to the English word "roan," some have suggested that Sabino Canyon was named for a horse that once grazed there, or for the mottled reddish color of its cliffs. These ideas may seem far-fetched, but no one has disproved them.

There is also an intriguing tradition that Sabino Canyon was named for a plant. But which plant? In Mexico sabino is a name applied to small-fruited conifers such as bald-cypress or juniper. The best candidate in Sabino Canyon is a beautiful tree called the Arizona cypress, but most cypresses grow several miles up the canyon, where early Spanish-speaking visitors would have been unlikely to see them. Only a few small, inconspicuous cypresses grow in the lower parts of the canyon today.

But today s Sabino Canyon is not the same as the Sabino Canyon of two hundred years ago. We happen to view Sabino Canyon at an unusually warm and dry time. In the eighteenth century, when Spanish-speaking people may have first set foot in Sabino Canyon, the world was nearing the end of a cooler, moister period, known today as the Little Ice Age. Such a climate probably caused many mountain riparian plants to grow farther downstream than they now do. If there had been even a few mature cypresses in the lower parts of the canyon then, these tall, symmetrical evergreens would have been the most striking trees on the canyon floor.

It seems likely that Sabino Canyon is just one of many Arizona canyons and streams bearing Spanish names for trees — the lovely green alamos (cottonwoods), fresnos (ashes), nogales (walnuts), and sabinos that relieved the austere landscapes encountered by early Hispanic immigrants to the arid Southwest.

The largest Arizona cypress in the lower reaches of the canyon today is dwarfed by nearby ashes and cottonwoods.

When Kino arrived, Apaches were already harassing Piman settlements. After the missionaries introduced livestock to the Pimans, the raiding escalated. Spanish soldiers and Piman warriors fought back and by the late 1760s were sometimes chasing the Apaches eastward all the way across the basin. A decade later they began to turn the tables on the Apaches, seeking out and destroying their acorn-gathering camps in the Santa Catalinas and elsewhere. In the 1780s the Spaniards constructed an adobe presidio at Tucson, replacing an earlier wooden fort, and began offering free rations to Apaches who would agree to settle peacefully nearby. In 1793 the first Apaches Mansos (Tame Apaches) moved in, marking the beginning of several decades of relative peace.

Even at the height of Spanish rule, enough hostile Indians remained to make travel to Sabino Canyon risky. If Tucson stood on "the rim of Christendom," Sabino Canyon was just beyond the rim, not tierra incognita, but a dangerous place nonetheless. The situation deteriorated after the Tucson Basin became part of the newly independent country of Mexico in 1821. The Mexican government could provide neither the reliable rations nor the constant military pressure that had subdued the Apaches, who resumed their raiding.

By this time an important event in Sabino Canyon's history may already have occurred. It is possible that sometime during the late eighteenth century a military detachment rode into Sabino Canyon on the trail of Apaches and gave the canyon the Spanish name by which we know it today.

Early Ranchers

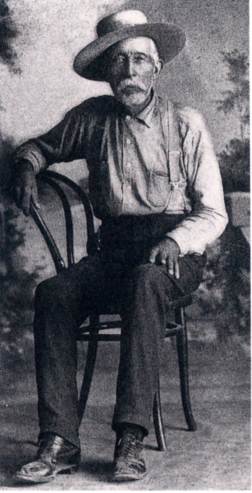

With the ratification of the Gadsden Purchase in 1854, Sabino Canyon and Tucson joined the United States. Two years later the Mexican garrison finally abandoned the old Tucson presidio, and a handful of recent American immigrants celebrated the historic occasion by raising the Stars and Stripes. Among them was a tall Virginian named William H. Kirkland, soon to become a Sabino Canyon pioneer.

In the late 1850s Tucson was not yet a boom town, but things were starting to happen. A stagecoach line connected the village to the outside world, boosting business. Ambitious merchants cashed in, supplying travelers, miners, distant army posts, and Tucson's own growing population. Surely Tucson would soon have its own United States Army garrison —a lucrative new market in itself as well as a source of better protection from hostile Indians. In this optimistic atmosphere, a few brave souls began to risk settling on the rivers and streams east of town.

Around this time Bill Kirkland built a ranch house on Sabino Creek, about a mile south of the canyon. We know almost nothing about Kirkland's ranch, but we can guess that he raised crops rather than cattle there, as an isolated herd might have offered an irresistible temptation to the Apaches. Kirkland made a good living from other ranches and a logging camp south of Tucson, and the outfit he called his "upper rancho" was probably never more than a sideline. But it was the first permanent settlement near Sabino Canyon in five hundred years.

The ranch changed hands several times in the difficult years that followed. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the army burned its forts in Arizona and headed east to fight, leaving the entire countryside open to Apache raiding. The budding economy collapsed, and many ranchers were forced to abandon their land and take refuge in Tucson. In 1866, after the war, Camp Lowell was established on the eastern edge of Tucson (near the present downtown area), but for many years this tent encampment provided little protection for distant ranches like the one near Sabino Canyon.

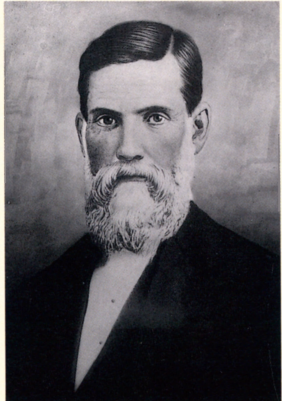

In 1873 the old Kirkland ranch was acquired by Tucson's wealthiest entrepreneur, Leopoldo Carrillo, an influential man with interests in mercantile sales, fruit orchards, real estate, and freighting, as well as cattle ranching. That same year Camp Lowell moved east to a site on the Rillito, just six miles downstream from Sabino Canyon, and the soldiers began constructing more permanent adobe quarters. By this time army campaigns and the establishment of reservations had reduced the Apache threat. Nevertheless, the next year one of Carrillo s vaqueros surprised several Apaches killing two head of cattle and barely escaped to report the incident at Camp Lowell.

William H. Kirkland, many years after he had sold his ranch on Sabino Creek. Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson.

As soon as Carrillo heard the news, he set out from town with five of his men. A mounted detachment of soldiers was already in pursuit, and Carrillo caught up with them after dark at the foot of the Santa Catalinas. The next morning they began tracking the Indians up Sabino Canyon. The going was rough, and it was evening, high in the mountains, when they finally found the Indians: twelve Apaches dressed in army uniforms and carrying passes from the White Mountain Reservation. They were on an official army mission to track down a renegade Apache named Chuntz, and they claimed the beef they had with them had been taken from hostile Indians. No one believed them, but little could be done. A month later, a company of Apache scouts, quite possibly the ones who had killed Carrillo s cattle, returned to the reservation bearing Chuntz s severed head.

ALMOST A RESORT

When city-dwellers were beginning to picnic in Sabino Canyon in the mid-i88os, Leopoldo Carrillo, by then owner of the old Kirkland ranch, was investing heavily in the entertainment of Tucsonans at a site closer to town. In 1886 he opened Carrillos Gardens, a grand amusement park just south of the city, with exotic trees, artificial lakes, a dance hall, a restaurant, and a menagerie. Now he found himself in the enviable position of owning land on a route to a newly popular mountain canyon. The results were predictable: "Leopoldo Carrillo went out to his Sabino Canyon Ranch . . . yesterday morning, to develop four large springs and run the water to one grand reservoir. This work is done preparatory to building a large hotel and baths, to be ready for the reception of guests next summer. Just what Tucson needs, and indeed, it will be patronized by people from all parts of Arizona . . ( The Arizona Daily Star,August 7, 1888).

Carrillo died two years later without having built his hotel. In a sense he had been ahead of his time. There would not be a resort hotel near Sabino Canyon until nearly a century later.

Leopoldo Carrillo. Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson: Buehman Collection.

Pleasure Parties and Picnics

Visitors to Sabino's canyon, in the foot-hills of the Santa Catalinas, report the place to be indescribably lovely, nature having bedecked the canyon in her forest beauties. As a resort for pleasure parties, the canyon is becoming immensely popular [The Arizona Daily Citizen, March 4, 1885].

By the mid-i88os, thanks to the bravery of army forces stationed at posts like Camp Lowell (by then renamed Fort Lowell), the long centuries had ended when travelers in the basin had risked their lives to Indian attack. Tucson had grown from a sleepy frontier town to a bustling city with schools, hotels, newspapers, and a population looking for new ways to spend its free time. City-dwellers discovered the beautiful canyon northeast of town, word spread, and by the time Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed the Santa Catalina Forest Reserve in 1902, Sabino Canyon was already a favorite getaway for Tucsonans.

Most visitors to Sabino Canyon at the turn of the century rode out from Tucson on horseback, or in horse-drawn carriages or wagons. One of the most popular routes was the same road we take today to Upper Sabino Canyon, but then it was a dirt track ending in a picnic ground at the confluence of Rattlesnake Creek and Sabino Creek. Beyond that point a narrow horse trail, called the Sabino Canyon Trail, or Apache Trail, wound its way up the canyon floor toward the high country. Another road led picnickers into the area we now call Lower Sabino.

When Sabino Canyon was a remote oasis at the end of miles of rutted dirt roads, a visit there was a real occasion, often planned well in advance and savored as long as possible. Typical were the day-long outings organized by the Ronstadt family, then already well known for its talented musicians and successful carriage-making business.

The extended family piled sleepily into their wagons before dawn and started down the long dusty road toward the canyon. Along the way they passed the picturesque ruins of Fort Lowell (abandoned in 1891) and later paused in the desert to hunt quail and dove. When at last they pulled under the trees in Sabino Canyon, they cooked a delicious breakfast of wild game, with beans and tortillas prepared in advance. During the heat of the day they relaxed near the stream, picnicking, exploring, and catching up on family news. It was toward evening when the family finally packed up and headed back. The men made the journey shorter by singing and playing their guitars until all arrived home at eight or nine o'clock, tired but content.

A light-hearted moment in Sabino Canyon, 1895. Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson: photo 57816.

YELLOW AND BLACK GOLD

For a short time near the end of the nineteenth century, people were drawn to Sabino Canyon by something more tantalizing than picnics or water projects. In 1892 a small group of men, including the mining engineer and railroad entrepreneur Col. Charles P. Sykes, staked claims to five gold mines near the mouth of Rattlesnake Canyon. An electrifying announcement followed: "Tucson is on the verge of experiencing one of the biggest mining booms known to the history of Arizona. If the statements of two of the best assayers in the territory are worth anything, the mines in the Sabino Canyon are as rich as any others in Arizona" (The Arizona DailyStar, June 19, 1892).

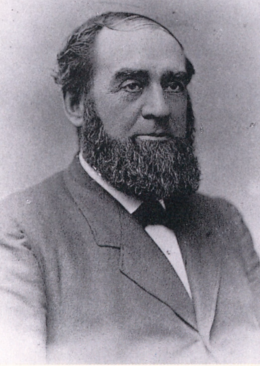

Three years later Sykes enlisted the backing of New York capitalists in forming the Sabino Gold Mining Company, and by 1897 the company had expanded its holdings to ten mines. Sadly for Mr. Sykes (but fortunately for Sabino Canyon), the claims never panned out. Today only short tunnels in the canyon walls remain as evidence of the hopeful enterprise.

The era of oil exploration was even briefer. In 1912 James F. McKale, a high school teacher fresh from Michigan, thought he had struck it rich in Lower Sabino Canyon. Years later he was able to laugh about his short career as an oil magnate. "Somebody had found a little grease on top of the water and I became a millionaire. With two or three other friends who had invested in that oil well, probably to the extent of a hundred dollars, we rented a Packard car . . . to go out there and see our property. It was the most wonderful feeling to know that I was a millionaire. I got over it shortly" (address to the Arizona Pioneers Historical Society, November 14, 1964, Arizona Historical Society).

"Pop" McKale later made his mark as a popular athletics coach at the University of Arizona.

Col. C. P. Sykes. Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson: photo 41045.

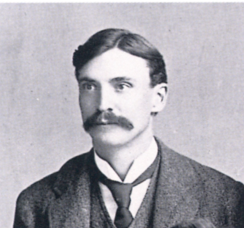

Professor Sherman M. Woodward in 1901, the year he conceived of a great dam in Sabino Canyon. Courtesy University of Arizona Library Special Collections Department.

Water for a Booming City

Meanwhile, events had been unfolding in Tucson that eventually would profoundly affect the distant mountain canyon. In the earliest days, Tucsonans had made do with water carried from springs, shallow wells, and the Santa Cruz. After 1882 water had flowed from the riverbed through an iron pipe. Enterprising individuals, realizing that even this new system could not supply the growing city forever, had turned thirsty eyes toward Sabino Creek.

In 1883 Calvin A. Elliott, a former forty-niner and merchant, posted a notice on Sabino Creek, claiming its flow for irrigation, stock watering, and furnishing water to Tucson. By coincidence, soon after that Fort Lowell began having serious problems with its water supply, and in 1886 an army engineer recommended piping water from Sabino Canyon. A few months later the army annexed the lower reaches of the canyon to the Fort Lowell Military Reservation. A heated dispute ensued, but in the end nothing came of either plan. Calvin Elliott was appointed Tucson's postmaster and abandoned his scheme, and Fort Lowell installed a steam-powered pump for one of its wells —a happy solution for the troops at the hot desert post, as the engine could also be used to power an ice-making machine.

These events were only a hint of things to come. In the last years of the century Tucsonans devised increasingly elaborate schemes for bringing the waters of Sabino Creek to Tucson, but none were carried out. Then, in 1901, Sherman M. Woodward, a young professor in the Department of Mathematics and Mechanics at the University of Arizona, formulated a plan so compelling that it would influence events in Sabino Canyon for nearly four decades.

The stream gauge constructed by Professor Woodward was a popular landmark for visitors to Sabino Canyon in the first decade of the twentieth century. Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson: photo 62886, Upham Collection.

Professor Woodward's dam site. Had the dam been built, the point from which this photograph was taken would have been submerged when the reservoir was full.

While most others had planned small dams near the mouth of the canyon, Woodward proposed a huge structure at a completely new site, more than three miles farther upstream, where the canyon narrows abruptly to a spectacular, sheer-walled gorge. (The location is about a mile beyond the end of the present road in Upper Sabino Canyon.) Woodward quickly claimed the necessary water rights, surveyed the dam site, and soon had a gauge constructed to convince potential investors that the stream flow was adequate. In 1904 he moved on to another university, but by then others were committed to his plan. Two years later they formed the Great Western Power Company and bought out Woodward s interests in the project.

The new company's plans rapidly grew more ambitious. By 1907 they included not only a 300-foot concrete dam at Woodward's site in Sabino Canyon, to create a large reservoir, but a smaller dam and reservoir in nearby Bear Canyon as well. An elaborate system of pipes, aqueducts, generating stations, and transmission lines would supply both water and electric power to the city of Tucson and open up thousands of acres in the Tucson Basin to irrigation.

ROADS TO THE PINE COUNTRY

At the turn of the century Tucsonans were already riding the rugged Sabino Canyon Trail (laid in 1896-1897 ) to camp, hunt, and escape the desert heat in the cool pine forests of the Santa Catalina Mountains. When the more direct Plate Rail Trail was finished in 1912, Tucsonans quickly adopted it as the new route of choice. A few years later John Knagge, together with his teenage sons Ed and Tom, took over a burro train serving the growing number of mountain cabins. The train became a traveling general store for vacationers in the Santa Catalina Mountains. The Knagges hauled families up the Plate Rail Trail at the end of May, kept them supplied all summer, then hauled them back down again at the end of August. They also carried provisions for miners, lumbermen, and forest rangers, and in December the braying burros trudged down Sabino Canyon loaded with Christmas trees.

The new trail was excellent, but travel on the back of a burro already seemed out-of-date to a populace that had become infatuated with the motorcar. In 1915 county voters approved a bond issue to build an automobile road up Sabino Canyon, but the project was delayed when a new estimate more than doubled its cost. Meanwhile, a road was completed up the north side of the Santa Catalinas in 1920, and Sabino Canyons burro train fell victim to progress. In 1931 a new survey for a southern road was made. Surprisingly, the Sabino Canyon route, long assumed to be the best, was rejected in favor of one starting up the slope several miles to the east. Federal prisoners began laying the present Hitchcock Highway in 1933 .

On the Sabino Canyon Trail, 1910. Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson: photo 8821.

In 1910 laborers began tunneling through the massive rock wall at the Sabino Canyon dam site, so that the stream could be diverted while the dam was raised. The old Sabino Canyon Trail, winding back and forth across the creek, was not suitable for delivering men and heavy materials to the dam site, so the company built an entirely new route, called the Plate Rail Trail, high on the eastern canyon slope.

But while the men worked, the stream gauge was telling a discouraging story. An extreme drought had dried out the creek, and the charts showed that had the dam already existed, the reservoir would have been nearly empty. Plagued meanwhile by water rights disputes, the company collapsed.

Although the Great Western Power Company never built its dams, it left its mark on Sabino Canyon. By 1912 the Plate Rail Trail had been extended up the mountain and a telephone line had been strung beside it. Eventually, the route came to be called the Phoneline Trail. You can still see remnants of the poles and wire today. At the old dam site the uncompleted diversion tunnel penetrates 125 feet into the canyon wall, and heavy iron eye-bolts rust slowly where they were driven into stone by determined men many years ago.

An Old Idea Revived

In the two decades following the collapse of the Great Western Power Company there were several attempts to resurrect the Sabino Canyon dam, but it took the upheaval of the Great Depression, with its huge government relief projects, to bring Professor Woodward s idea back to life.

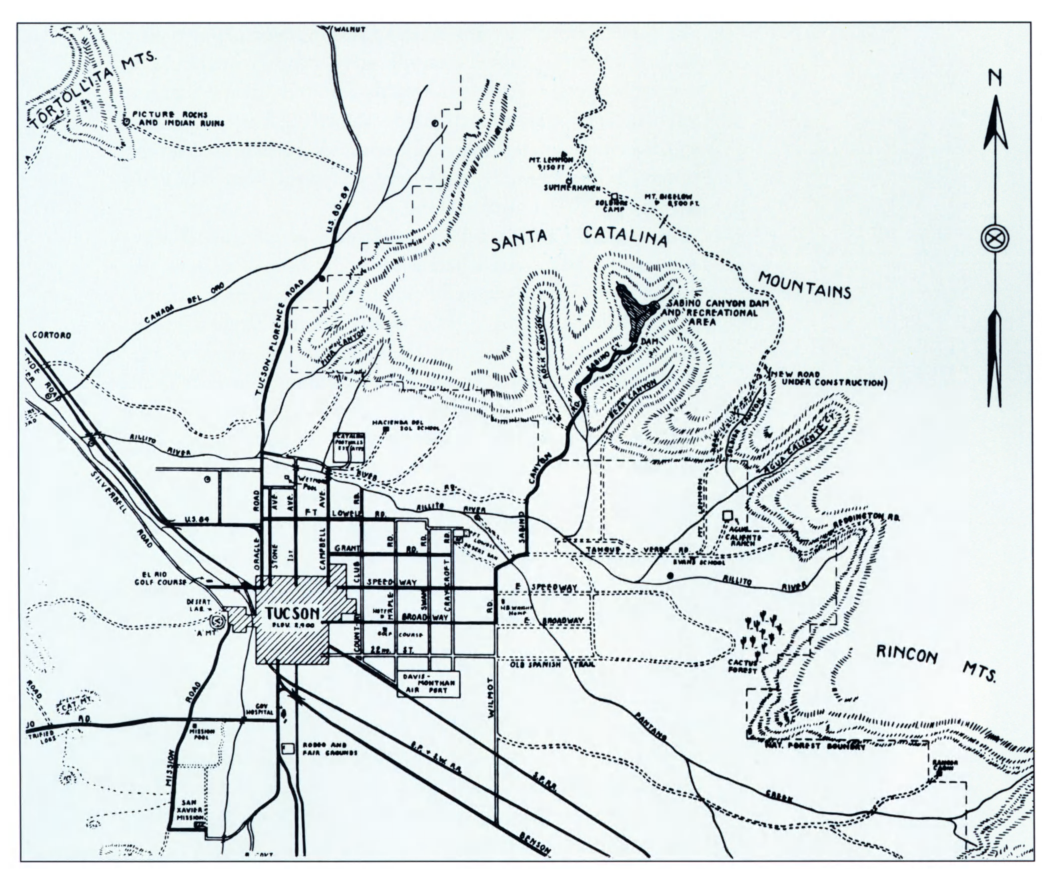

In 1933 the Tucson Chamber of Commerce began energetically advocating a federal dam at Woodward's site in order to boost the city's faltering economy. By this time Tucson had developed other sources of water and electricity, so in its new incarnation the dam would provide neither. What the city needed now, or so many believed, was tourists. The Chamber envisioned a great lake in Sabino Canyon, a recreationist's paradise with boating, fishing, camping, and cabins. Streamside camping and picnic grounds would be created downstream along a picturesque access road. The route would cross the creek nine times over rustic stone bridges, each of which would also act as a small dam and form an inviting recreational pond.

A promotional map published in 1936, prematurely showing the huge dam and reservoir that were never completed in Sabino Canyon. Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson: map 678.

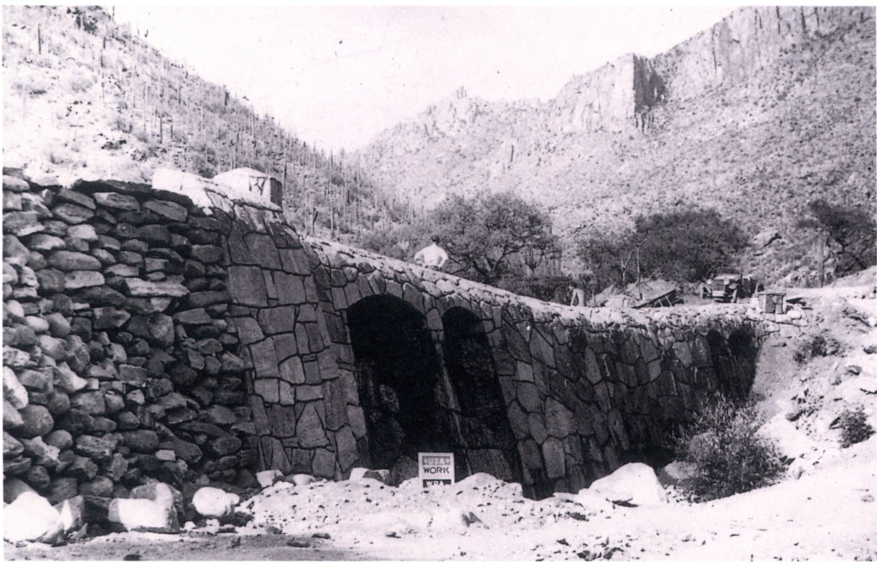

In fall 1934 laborers for the Emergency Relief Administration, or ERA, began blasting out new roadbed beyond the old picnic grounds at Rattlesnake Canyon. The workers were homeless transients who had been uprooted by the nation's economic crisis and drawn to Tucson by its warm climate. Pleased to be doing productive work in beautiful surroundings, the men laid out two hundred yards of roadbed in the first week. Within a month, Tucsonans were applying to the Forest Service for lakeside cabin permits. The next year, after four bridges had been built, men from the Works Progress Administration took over. The Chamber of Commerce and the Sunshine Climate Club printed a map showing the "Sabino Canyon Dam and Recreation Area" as though they already existed. The route from the city was surfaced so that Tucsonans would be able to drive to the lake entirely over paved roads. The last of the nine stone bridges was finished, and the road began climbing the eastern canyon wall in the final approach to the dam site.

The seventh bridge in Upper Sabino Canyon, nearing completion in 1936. National Archives photo 69-NS-30160.

But in their enthusiasm most Tucsonans were overlooking an essential fact: No funds had been allotted for construction of the dam itself.

In late summer 1936 the Army Corps of Engineers held a public hearing in Tucson to settle the fate of the Sabino Canyon Dam. The meeting room was packed. One after another, citizens and government officials testified unanimously in favor of the project. A month later the Corps issued its anxiously awaited report. It concluded with a recommendation that the dam be built, provided that "local interests are willing to contribute $500,000 toward the project." This last sentence was the death knell for Pima County's greatest relief project. The county had offered to contribute only $600. Construction of the access road halted a mile short of the dam site.

Brass plaque on a bridge in Upper Sabino Canyon

Anglers on the dam in Lower Sabino Canyon, 1939. Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson: photo 7259.

We had almost lost Sabino Canyon. The Great Western Power Company's dam would have diverted the entire flow of Sabino Creek outside the canyon, drying up the stream and destroying its precious aquatic and riparian habitats. The effects of the Depression version of the dam would have been more insidious. By eliminating flooding and providing a nearly constant year-round discharge into the creek, it would have drastically disrupted the ecology of the riparian communities downstream. Fortunately for the future of Sabino Canyon, Professor Woodward's dam site was put out of reach of engineers when it was included in the Pusch Ridge Wilderness in 1978.

A New Recreation Area

The New Deal left more in Sabino Canyon than a road to nowhere. After the WPA took over the work in Upper Sabino Canyon, the ERA turned to building roads and campgrounds in Lower Sabino. Meanwhile, the Civilian Conservation Corps (ccc) had also been working on recreational facilities and had constructed a new ranger station just west of the canyon. In June 1937, after the demise of the great dam at Professor Woodward's site, the ERA'S transient laborers began building a much less grandiose structure in Lower Sabino Canyon. The following spring two thousand Tucsonans turned out to hear the speeches at the dedication ceremony, held to the strains of a combined junior high school orchestra. It was far less than they had hoped for, but Sabino Canyon finally had a dam after all.

The tiny lake was instantly popular. The centerpiece of the new Sabino Canyon Recreation Area, it regularly filled with swimmers, and fisherman crowded the dam angling for stocked bass and sunfish. Today the lake has long since silted in, and only a shallow pond remains. Trees have grown up in the sand, and Sabino Lake is now a favorite destination for birdwatchers from around the country.

The 1930s saw the beginning of heavy use of Sabino Canyon. The number of visitors skyrocketed after World War II, as Tucson's population boomed. The Forest Service responded by building new facilities and closing the canyon at night, but it was not enough. On busy days the canyon walls rang with the sound of automobile horns, and the air reeked of exhaust.

The era of the private car in Sabino Canyon ended unexpectedly in 1973, when the canyon was temporarily closed to cars for repairs and improvements to facilities. Visitors walking or bicycling in smelled the clean air, heard the quiet, and urged the Forest Service to close the gates permanently to traffic. Others objected, and there were angry debates in the editorial pages of Tucson's newspapers. In the end the Forest Service compromised with a shuttle bus service. Since 1978, when the first shuttle ran in Sabino Canyon, the shuttle has itself become a popular tourist attraction.

CAMP LIFE

Laborers employed by the Emergency Relief Administration during the Great Depression constructed many of the facilities we see today in Sabino Canyon. Life in their small camp in Upper Sabino was less than luxurious, but residents like Bill Griffin, grateful to be working during those difficult years, laughed at trying conditions. "Rain! . . . In some of the tents we had all of an inch of water on the floor and two inches on the beds with a continual promise of more to come. I was warned not to put my hand on the wet canvas as that would cause it to leak. Leak? I came dern near drowning —and I didn't touch the d—d canvas. It's fun to lie on ones bed and look up at the water streaming down the outside (and inside) of the tent, and to count the tadpoles and pollywogs, along with fish worms and wondering whether the next fish to slide down will be a trout or a perch" (TheOasis, October 11, 1935, Arizona Historical Society).

The Emergency Relief Administration camp in Upper Sabino Canyon, after wooden roofs had replaced the leaky canvas covers over the laborers cabins. Courtesy Coronado National Forest.

Sabino Canyons Future

For thousands of years Sabino Canyon offered precious food and water to hunter-gatherers and farmers. In the last century and a half Tucsonans have come to the canyon seeking ranch-land, water, electric power, and gold. Most recently we have sought the quiet pleasures of nature and a retreat from city life.

In the 1980s Tucson's expanding suburbs reached Sabino Canyon. On crowded weekends today, visitors may see more of each other than of wildlife. A century after city-dwellers began spreading their picnic cloths under the cottonwoods, Sabino Canyon faces the same uncertainties as popular natural areas throughout the country. Will we "love it to death"? Or will we preserve Tucson's oasis to delight and inspire us into the twenty-first century and beyond?

Children on a field trip to Sabino Canyon. Courtesy Sabino Canyon Volunteer Naturalists.

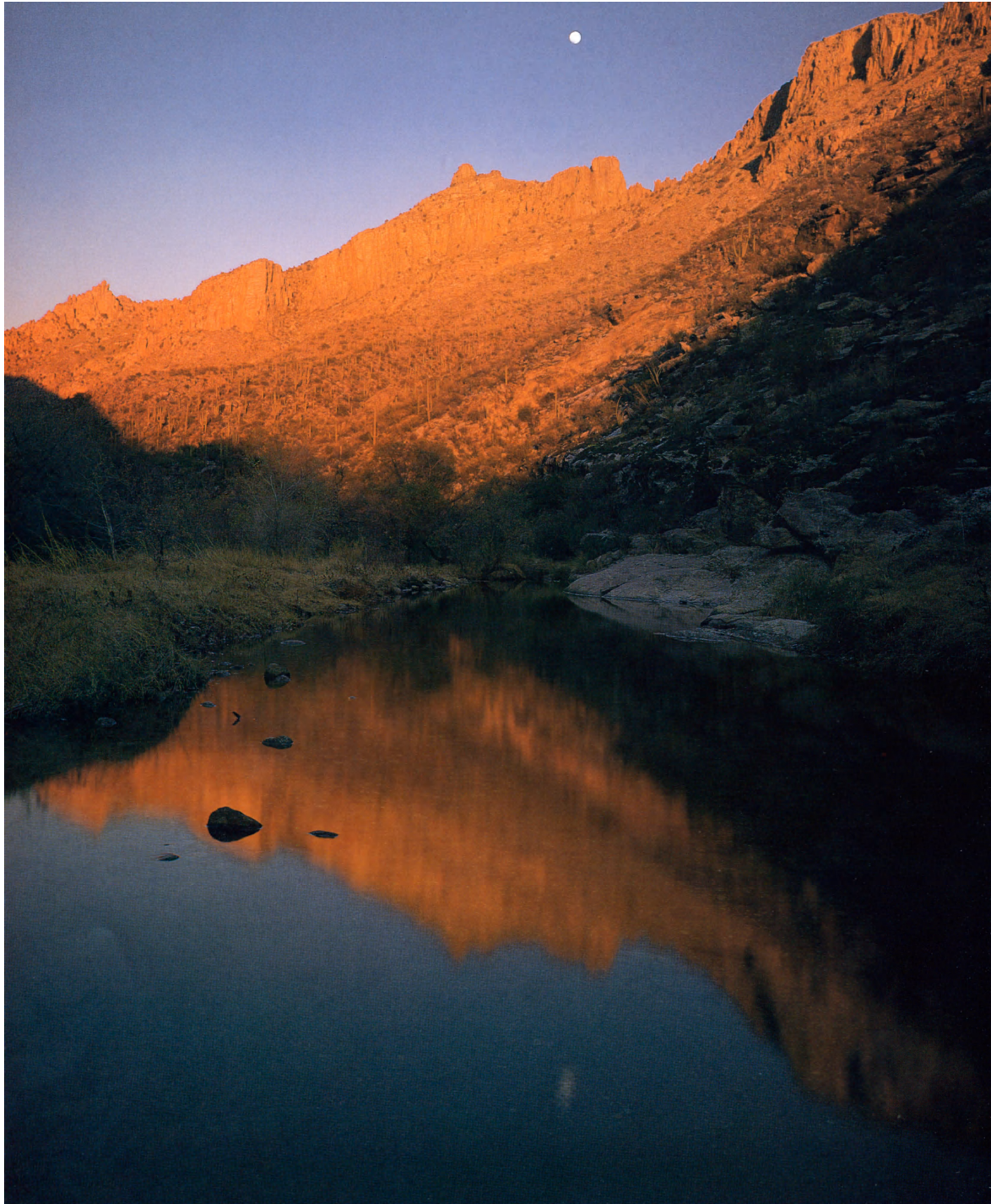

Mid-winter moonrise