The silent era is celebrated for its innocence. The charming picture it presents of America in the early years of the century has led people to assume that life was quieter then, gentler and more civilized. But the silent era recorded another America. It revealed the corruption of city politics, the scandal of white slave rackets, the exploitation of immigrants. Gangsters, procurers, and loan sharks flashed across the same screen as Mary Pickford, but their images have mostly been destroyed, leaving us with an unbalanced portrait of an era.

This book is an attempt to set the record straight. I believe that one day, those films which give us an accurate impression of how people lived will be regarded as precious as the most imaginative flights of fiction.

Our view of the silent era is conditioned by the minuscule number of films in circulation—films which have selected themselves by virtue of their availability. This book will show the astonishing range of subjects dealt with in that period. While few of these films made history, all of them—if only for a few moments—recorded it.

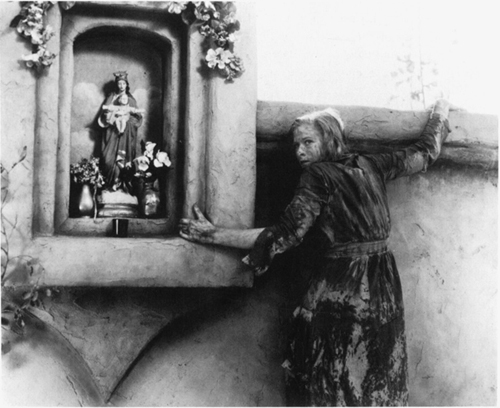

Lois Weber exposes corruption in American politics with The Hypocrites, 1915. The grafting politician is paid off by the gangster, the cop, the saloonkeeper, the madam, and the drug dealer. (The madam is Jane Darwell, of Grapes of Wrath fame.) (National Film Archive)

The early films were made to a pattern which had proved its commercial value on the popular stage. Give the audience someone to identify with, bring in “heart interest,” a pretty girl or an appealing child, and wind up with a happy ending. Into this you can mix whatever theme you want. Banal it may sound, but some remarkable films were made with this formula.

Some smothered their subject matter with glutinous sentimentality. They were old-fashioned in the worst sense. A critic of 1913 described them as exhibiting “a feeble-minded subservience for what may have served some past generation but which has no bearing on this one.”1 Other films adopted plain stories and a straightforward approach, which became the trademark for American films. Their very directness appealed to audiences, but often disturbed those in authority. Strong themes unimpaired by symbolism or sentimentality brought down upon the industry the wrath of clergy, reformers, and politicians alike.

If the subject of prostitution were to be shown, a parable set in Biblical times might (just) be acceptable to the bluenoses. Imagine their shock when upon the screen appeared modern settings, realistic playing, and equally realistic prostitutes! No matter that such films were animated by reforming zeal. What of their effect upon adolescent boys? They must be stopped.

Sadly, even these realistic films stopped short of attacking the system that led to prostitution. Melodramatic devices would place the police in the role of heroes; a love affair would end a corrupt regime in City Hall; an evil factory owner would be redeemed by a worker’s child. Melodrama was an antidote to the sting of truth.

Nonetheless, that sting sometimes penetrated the hokum, to the discomfiture of those in authority.

They took their ideas from the newspapers. The stories of many one- and two-reelers, especially those of D. W. Griffith, were adapted from current issues. Many workers, illiterate and foreign-born, read no newspapers, and the nickelodeon was thus a source of astonishment. Nickelodeons were sometimes seen as breeding grounds for crime and sedition. Surveys had shown that almost three quarters of the audience of such places came from the working class.

As late as 1920, a member of the Canadian Parliament declared that pictures were an invitation to the people of the poorer classes to revolt. “They bring disorder into the country. Thank God there is not a moving picture show in any town or village in my constituency, and I hope that there will not be any for a long time.”2

The movies were born into the era of reform, which (roughly) opened with the inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt in 1901 and closed with the entry of the United States into the First World War in 1917. The optimism with which it began was still evident in 1916 when a clubwoman declared, “Motion pictures are going to save our civilization from the destruction which has successively overwhelmed every civilization of the past. They provide what every previous civilization has lacked—namely a means of relief, happiness and mental inspiration to the people at the bottom. Without happiness and inspiration being accessible to those upon whom the social burden rests most heavily, there can be no stable social system. Revolutions are born of misery and despair.”3

“Mrs. Raymond (Julia Swayne Gordon) makes a secret visit to her gambling palace”—Vitagraph’s The Sins of the Mothers, 1915, written by Elaine Sterne, winner of the $1,000 New York Evening Sun Photoplay Contest. (Robert S. Birchard Collection)

If the movies never quite lived up to the reformers’ expectations—either by preventing revolution or by causing it—they did eventually become the most powerful medium of communication in the world—a universal language. In order to outdo the rivalry of the press, they had to forego what a newspaper contained—hard news, preaching, and propaganda—and become a reliable source of entertainment. Soon, even newsreels were full of hokum, extolling flagpole squatters and stunt flyers, but avoiding industrial or political unrest. In the twenties, if a film set out to educate rather than to entertain, audiences knew, by some sixth sense, how to avoid it.

“Why in the world does anybody want to see life represented on the screen as it is?” asked a Florida fan. “How can they stand to see anything so monotonous? We all see these commonplace things every day of our lives and when we go to the theatre we want something unreal and beautiful to give us courage and hope to face the trials of this drab world of ours … So please, Mr. Directors, give us not life as it is but as we would like it to be.…”4

Countless social or message pictures had played on people’s sense of outrage, and they had grown tired of feeling ashamed or indignant when they went to the movies. A producer’s wisecrack—“If you want to send a message, send it Western Union”—summed up the desire to rid the movie theatre of the problem picture. As people stayed away from war films once the war was over, so they stayed away from social pictures once the era of reform was over.

The term “progressive” at the turn of the century referred to a breed unlike the left-winger of today. It meant a reformer, an enthusiast for moral uplift, and a campaigner for liberal reform. “Muckraking” journalism flourished at this period, exposing injustices and arousing the social conscience of the movement.

Progressives were particularly concerned with the problems of the city; most shared the old agrarian idea of the city as the heart of moral corruption. And the cities were expanding at a terrifying rate.

While most progressives were opposed to monopolies, political machines, and labor unions, they were no more united in aim than in politics and are as hard to generalize about as they were to categorize. Among their number were Eugene Debs, leader of the Socialist party, and Senator Tom Watson, a populist and a racist. While some were concerned and compassionate, like Jane Addams of Hull-House, the pioneering settlement in the slums of Chicago, others were little more than moral police. When they won control, they brought liberal reform to an end. As Robert Sklar wrote, they were anxious to control access to information so the lower classes should remain ignorant of the social system in which they lived.5

Mostly middle class, invariably Protestant, and the backbone of their communities, these moral police kept a stern eye on the leisure activities of the working class. Its fondness for drink was being dealt with. Now appeared a social disease quite as insidious in its effects as alcohol—“nickel madness.” By 1910, 26 million people in the United States were frequenting the five-cent theatres every week.6

It was “the academy of the working man, his pulpit, his newspaper, his club.”7 Largely operated by the foreign-born, the craze threatened to undermine all the institutions Americans held dear. It had to be controlled by responsible people, and the most effective form of control was thought to be censorship.8 “For all of their faith in the limitless capacity of mankind,” wrote William Drew, “Progressive leaders were often quick to shield the public from ideas they considered harmful.”9

Yet many were convinced that the amazing progress of science and technology would solve the problems of society—and involved in that progress was the moving picture. They felt it should be used for propaganda, which had not yet become a dirty word. Dr. H. E. Kleinschmidt of the Tuberculosis Association described good propaganda as “mental inoculation” whose goal was “will control … through education.”10

The industry, seeing all reformers in the guise of censors, wanted nothing to do with them, even though films were made of many subjects close to the reformers’ hearts, such as prohibition and child labor. D. W. Griffith was particularly contemptuous of them. In 1913, he made an extraordinary film called The Reformers, or the Lost Art of Minding One’s Business. A candidate for mayor, with his wife, campaigns around town11 on an antivice platform, closing saloons and theatres. Safe at home, their adolescent children read racy magazines and imbibe alcohol, and (by implication) the daughter is seduced by the local wastrel. Keeping children ignorant seldom keeps them innocent, says Griffith. And if you close the saloons, liquor will circulate in secret. Two of his reformers are obvious homosexuals, and Griffith goes so far as to show prostitutes, dressed as pious churchgoers, continuing to ply their trade. (Three years later, he struck reformers even harder with Intolerance, causing such shock and distress that on its reissue it had to be amended.) Yet Griffith, whether he liked it or not, was part of the progressive movement, and many writers have called him a reformer himself.

The relationship between reformers and the industry deteriorated to the point of open warfare. In 1921–1922, during the Fatty Arbuckle and William Desmond Taylor scandals, the moral police—particularly clubwomen and church groups—summoned such power that they made the industry fear for its survival. It was dependent on the family audience, so it had no alternative but to create a figure-head, a sort of Moses with a fresh list of commandments. But by that time, the political climate had changed and the movies reflected the new conservatism. Social films were fading away.

“As the poor became less important as the mainstay of the movies,” wrote Lewis Jacobs, “the ideals and tribulations of the masses lost some of their importance as subject matter for the motion picture. Patrons of the better-class theatres had more critical standards, more security in life, and different interests.… Pictures began to be devoted almost exclusively to pleasing and mirroring the life of the more leisured and well-to-do citizenry.”12

In all my years as a silent film historian and collector, I had found so few social problem films that when I contemplated this book, I wondered if there was enough material. But as I began to dig, and as my generous fellow historians William Drew, George Geltzer, J. B. Kaufman, and Q. David Bowers sent me material from America, I became overwhelmed by the sheer number of such films. I never dreamed they had been produced on such a scale or had taken so radical a viewpoint. While it proved frustrating to have to leave out so many fascinating films, the research has given me a new insight into, and a new enthusiasm for, the period.*

So many social films were made that a reviewer talked of a plot being “typically sociological.”13 (A large proportion were three- and four-reelers, which seem to have perished in greater numbers than one-reelers, or even features.)14 Yet by the late silent period, social films were almost unknown. On the rare occasion a writer tackled a problem drama, he could be sure that his brainchild would be unrecognizable if it failed to be slaughtered first.

Sam Ornitz15 wrote a story about an unmarried mother for Josef von Sternberg; as he described it at the time, “She’s been seduced and has a baby, which is the only thing she lives for. In fact, to provide for it she is at last driven to the streets. Then one of these interfering societies—America is lousy with them—steps in and has the baby taken from her. Says she isn’t fit to bring it up. Why, they might as well tear the heart from her. The rest of the play shows the girl’s attempts to drag herself back to social responsibility to get the child again.”16

Von Sternberg’s scenario writer, Jules Furthman, fresh from his triumph with The Docks of New York (about a sailor and a prostitute) wanted to change the story, which angered Ornitz.

“Look here, Sam,” said Furthman, “We’ve just done a story with that kind of atmosphere in it; we can’t do two, one after the other, exactly alike.”

He and von Sternberg decided to set it in Vienna, in its prewar glory. And Furthman felt that the heroine could hardly be a streetwalker: “We’ll just have to make it so she’s poor and can’t nourish the kid properly.” Then came another creative bloodletting: “You know, old man, this unmarried-mother stuff won’t go with the great American public, so we’ll have to make it seem like she was seduced by the young man of the house.…” And so the realism was smoothed away, and the picture ended up artistically impressive but completely escapist. Never mind; The Case of Lena Smith was a success and Sam Ornitz was promised a thousand-dollar bonus. “So I have to keep my mouth shut,” he said, disgustedly, “because I’ve got a wife and kids over here.”17

Esther Ralston in Josef von Sternberg’s The Case of Lena Smith, 1929. (National Film Archive)

By this period, the star system was in full swing, and a “star vehicle” was hardly the right conveyance for burning issues. In the early days, by contrast, a well-known player would often be happy to tackle a difficult subject, regarding it as a challenge.

The early social films often contained precious historical evidence. Some were shot in the slum districts of the big cities; others featured the very people at the storm center of controversy. They were not always popular with exhibitors or even audiences, but they were endured, for a while, as a child endures castor oil.

“I don’t like such things,” complained a reviewer of In the Grip of Alcohol (1912). “I don’t believe the motion picture playhouse the place to see gruesome, heartbreaking tragedies. I wouldn’t want my little boy to look at that set of films. But that it teaches a terrible lesson, and may perhaps be a terrific force for good, I am not prepared to deny.”18

A film like In the Grip of Alcohol could only have been made in the early years. Once prohibition had taken effect, scenes of people drinking—indeed any violation of the Volstead Act—had to be treated with the utmost discretion. Those early years, before 1919, were the richest source for social films, which is one reason why there are fewer firsthand interviews in this book than I would wish. The pioneers of the social film have long since gone. Fortunately, some talked to the trade press, and one or two left memoirs. Occasionally, I was able to talk to those who had worked with them. But most left nothing, not even their films.†

The makers of the early social films—George Nichols, Barry O’Neil, Oscar Apfel—were not lionized as were popular directors of later years. Many were stage people, reaching the end of their careers. Few continued making films into the twenties.

Only one filmmaker in America devoted an entire career to making what were known as “thought films.” That filmmaker was a woman, Lois Weber, who worked as a reformer within the industry. Born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, and educated in Pittsburgh, her ambition was to cultivate her voice in New York. Her parents refused, so she ran away, with eight dollars, only to find her music instructor had gone abroad. Too proud to return home, she endured the kind of poverty she so vividly captured in her films. At one point she had to sing in the street for food. She spent two years as a social worker in the slums of Pittsburgh and New York and worked as a missionary among the prisoners on Blackwells Island.20

Eventually, she joined a musical comedy company, became an actress, and met her husband, Phillips Smalley.21 But she never forgot the immigrants and their struggles. “I came suddenly to realize the blessings of a voiceless language to them,” she said.22 As a filmmaker she decided to make what she called “missionary pictures.” Some of these she made with her husband (both were Christian Scientists), but she was always the dominant partner. “I like to direct,” she said, “because I believe a woman, more or less intuitively, brings out many of the emotions that are rarely expressed on the screen. I may miss what some of the men get, but I will get other effects that they never thought of.”23

Lois Weber, the “picture Missionary.” (Kobal Collection)

The range of subjects Weber tackled was as astonishing as the speed with which she produced them. Suspense (1913) outdid Griffith in its technical wizardry.24 Civilized and Savage (1913) had Smalley as a white man nursed to health by a black woman (Weber), who, her task complete, sets out to find his wife.25 The Smalleys handled a story about Jews with great care, even calling in an advisory body of rabbis, who objected only to the title, The Jew’s Christmas (1913).

In 1915, Weber created her first sensation, The Hypocrites. A four-reeler made the previous year for Bosworth, it was held back because of its inflammatory treatment. Using an allegorical style, with multiple exposures, to flay politics, big business, and the church, it further shocked the establishment by having a naked girl play the figure of Truth. Audiences flocked to see the nudity and were then obliged to sit through the moral lesson, upsetting to many of them. The nudity was filmed so innocently than few boards of censors could ban it. There were several attempts; the Catholic mayor of Boston demanded that Truth be draped, so clothes were allegedly painted, frame by frame, onto the film!26

After making films about such subjects as families destroyed by scandal mongering, Weber and Smalley played together in Hop, The Devil’s Brew (1916), a drama of opium smuggling.27 Where Are My Children? (1916) was unique: a film attacking abortion which nonetheless defended birth control.

Curiously, Weber referred to such films as heavy dinners. “Anything that promises red lights will crowd the box office,” she said in 1918. “I don’t want to produce that type of play. I want to give the public light afternoon teas—that is what I term the light, artistic production, the one which charms the eye, leaves a pleasant fragrance behind it, and which is accompanied by music of just the proper sentiment.”28

Fortunately, she had made several heavy dinners by that time, including Shoes (1916), a parable of poverty inspired by a paragraph in a Jane Addams book about a working girl who, after months of resistance, “sold out for a pair of shoes;”29 The People vs. John Doe (1916), an anticapital punishment saga; Even As You and I (1917), which showed how a young couple resisted temptation—until drink dragged them down;30 and The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1917), a salute to Margaret Sanger and her birth-control campaign.31

Lois Weber continued to make social films well into the Jazz Age, when she suffered the rejection of audiences. She and Phillips Smalley were divorced in 1922—he had become an alcoholic—and her company failed. She made a few more pictures, one of which, The Angel of Broadway (1927), combined the cynicism of the twenties (nightclub parodies of the Salvation Army) with the commitment of the reform era (social work in the slums). It was her last silent film, and by 1930 she was managing an apartment building.32

She made a minor film in 1934 and died in 1939, the same year as Phillips Smalley. Both were forgotten. Neither talked, as far as is known, to any historian, nor did they leave their memoirs. So most of their memories have been lost, along with most of their films.

Some of those who made social films were unaware they were doing so. An example is Raoul Walsh, who made Regeneration for Fox in 1915. The story, based on fact, of an Irish gangster reformed by a girl from a settlement house, is one of the most effective social films of its era. Yet it is clear, both from Walsh’s memoirs and from my own interview with the man, that he never thought of it as such, but as a strong story which he told with as much punch and realism as he could. It was the same with King Vidor. He did not regard The Crowd (1928), arguably the finest silent social film, as a work of social or political value at all. The theme fascinated him, and he persuaded MGM to let him go ahead and make it. “I didn’t know it was a social film,” he told me with an ironic smile, “until people like you told me.”

Even Mrs. Wallace Reid, whose most significant social film was Human Wreckage (1923), a treatise against drug addiction, was uncertain of the term:

“I was making what they call … not problem pictures, but I mean pictures of that kind.”

“Social films?”

“Yes, more or less, but I tried to do it with a plot which was interesting enough to hold people. And I tried to give them a message at the same time.”33

I must admit that the term “social film” is imprecise and even misleading. (It is such a useful one, however, that I shall continue to employ it.) In Hollywood, with its painful memories of McCarthyism, the term is confused with “socialist.” Willis Goldbeck grew angry when I used it. I hoped that as a screenwriter, journalist, and later director, he would give me an illuminating explanation of why so few social films were made in the twenties. But he bridled at the question. “We made entertainment until the liberal element came along,” he snapped. And he wanted nothing more to do with anyone who could ask such a question.

One thinks of Hollywood people as frivolous and apolitical; some of them undoubtedly were. Colleen Moore told me there was very little interest in politics in the twenties: “We were only interested in Paramount, Universal, MGM—who was president of them, not who was president of the United States.”34 Yet when Judge Ben Lindsey visited Hollywood in the late twenties, he found the same interest in the great social and economic problems that he had met at the table of Jane Addams of Hull-House in Chicago.35

At that period, however, such problems were not the kind of thing anyone thought of making films about. With America in control of the film markets of the world, its product had to appeal to an international audience. American social problems like prohibition were of little interest to Europe, while wider issues—poverty, strikes—stirred up uncomfortable fears about Bolshevism and were therefore avoided.

Such films were made, however, if not always by the film industry. The most extreme—and extraordinary—example was The Passaic Textile Strike (1926), produced by the embattled strikers themselves and used to raise money to sustain the strike. It was the discovery of this film which finally led to the writing of this book. For years, I had regarded it as a book which I would write “one day.” Without seeing The Passaic Textile Strike, I felt it was not worth starting. But when I visited New York’s Museum of Modern Art in September 1983, curator Eileen Bowser told me that the film had been found in the collection of Tom Brandon. A few moments later, I was watching it, and a few weeks later I was talking to one of the organizers of the strike, who had also played a role in the film. Subsequently, Eileen Bowser and Charles Silver, Supervisor of the Film Study Center, made available many documents from the Brandon collection which proved invaluable.

I feel drawn to the subject of social films not only because I have been a film historian for so long, but because I have a degree of sympathy for everyone’s point of view. When I was a filmmaker, I made what might be called social pictures. I saw for myself how hard it was to attract audiences. As a filmgoer, I tended to betray my own aspirations and head for the enjoyable rather than the educational. This paradox may have something to do with my background. Although I was born in England, my father came from Southern Ireland, with its rich tradition of theatre and storytelling. But his father came from the Protestant North, with its puritan distaste for entertainment. Without knowing it, my father passed on both traditions to me. So I understand the censor and the prohibitionist, while sympathizing with the rebels who fought against them.

I am sometimes asked why I stick so rigidly to the silent film. Were no worthwhile social films produced in the thirties? Of course there were. But many books and articles and even documentary films have covered this area, whereas hardly anything has been written about the silent social films, resulting in a dismissal of the period.‡ Thanks to recent revivals, the silent era has at last been accepted as a rich source of artistic innovation. But social films? “By and large,” said one historian, “ ‘social issue’ films did not make an appearance until the thirties.”36

Mill girls on the picket line: The Passaic Textile Strike, 1926. (Museum of Modern Art)

Historians can be forgiven for avoiding the period because so many of the films are “unavailable for study,” i.e., lost. But I am also a film collector, and the first rule of the collector is never to give anything up as “lost.” My book The War, the West and the Wilderness led to several of the “lost” films discussed in its pages coming to light. This book has already had a similar result, including the recovery of a Lois Weber film, recut for European release.

There are some films which I suspect would replace many of the accepted classics if only we could see them. Yet the most promising title—like the suffragist film Eighty Million Women Want—can nonplus the most devoted film scholar, while a commercial gangster film from the Fox studio can stand among the most impressive achievements of the entire period.

It would be cynical to say that a title has to appear in print before it is taken seriously, but often a description of the plot alerts the memory of an archivist. (If you know of any old films in their original state—35mm nitrate—I urge you to get in touch with me c/o the publisher.)

If more of these social films could be rediscovered, what a panoply of American history they would represent!

KEVIN BROWNLOW

Postscript

In The War, the West and the Wilderness, I made an attempt to list all those films I understood to be lost. Since then, I realize that this was a waste of time. Until all the archives of the world fulfill their obligation and publish lists of their holdings we will never know what survives and what doesn’t. A partial list has been printed by the Federation of Film Archives (FIAF), but I am told it can only be consulted by “authorized” people. A number of archives refuse to reveal the contents of their vaults. We will never know what we have lost. Nineteen-ninety inaugurates the last decade of nitrate—much of it has lasted well beyond the fifty years predicted for it. It is not expected to last into the new century. Yet still many archives are nothing but vast depositories, lacking the finances to copy their fast-decomposing nitrate. Unless the archive movement can be properly funded to make the best possible copies of its precious original prints, posterity will judge us harshly.

K. B.

* I have not dealt with the longest of all, Erich von Stroheim’s Greed, originally forty-two reels. For one thing, so much has been written about it; for another, in its cut version the social elements were largely honed away. I have kept my references to Intolerance and The Birth of a Nation to a minimum, since definitive studies exist on both, one written by William Drew. (D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance, McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640.) I have been obliged to cut a section on films about blacks for reasons of length—but far better studies of the subject have been written by Thomas Cripps and Daniel J. Leab.

† Luckily, other voices from the past have much to say on their own account: the reviewers for the trade papers, fan magazines, and newspapers. Their opinions are less important than the attitudes they unwittingly display. Wherever possible, I have quoted verbatim both the review and the story of a film, the description of the time being so much more resonant than a paraphrase.19

‡ Kay Sloan has since written The Loud Silents, Origins of the Social Problem Film (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988).