Since Earth’s very beginning, about 4.6 billion years ago, natural forces have pummelled and scoured our planet, embellishing its surface with intricate patterns and unique shapes, a patchwork so vast and complex that it can only be truly appreciated from space. Rugged mountain chains are pushed skywards and then worn down again by the many processes of erosion. Ice breaks up rocks, water carves out snaking river valleys, and wind blows shifting sands into vast fields of rippling dunes in an endless cycle of destruction and renewal. Shapes can appear overnight or evolve over millennia, with many created by life itself. It is what makes our planet so unique; and now we humans are leaving our indelible mark, adding our own designs to the infinite variety etched onto the surface of our patterned planet.

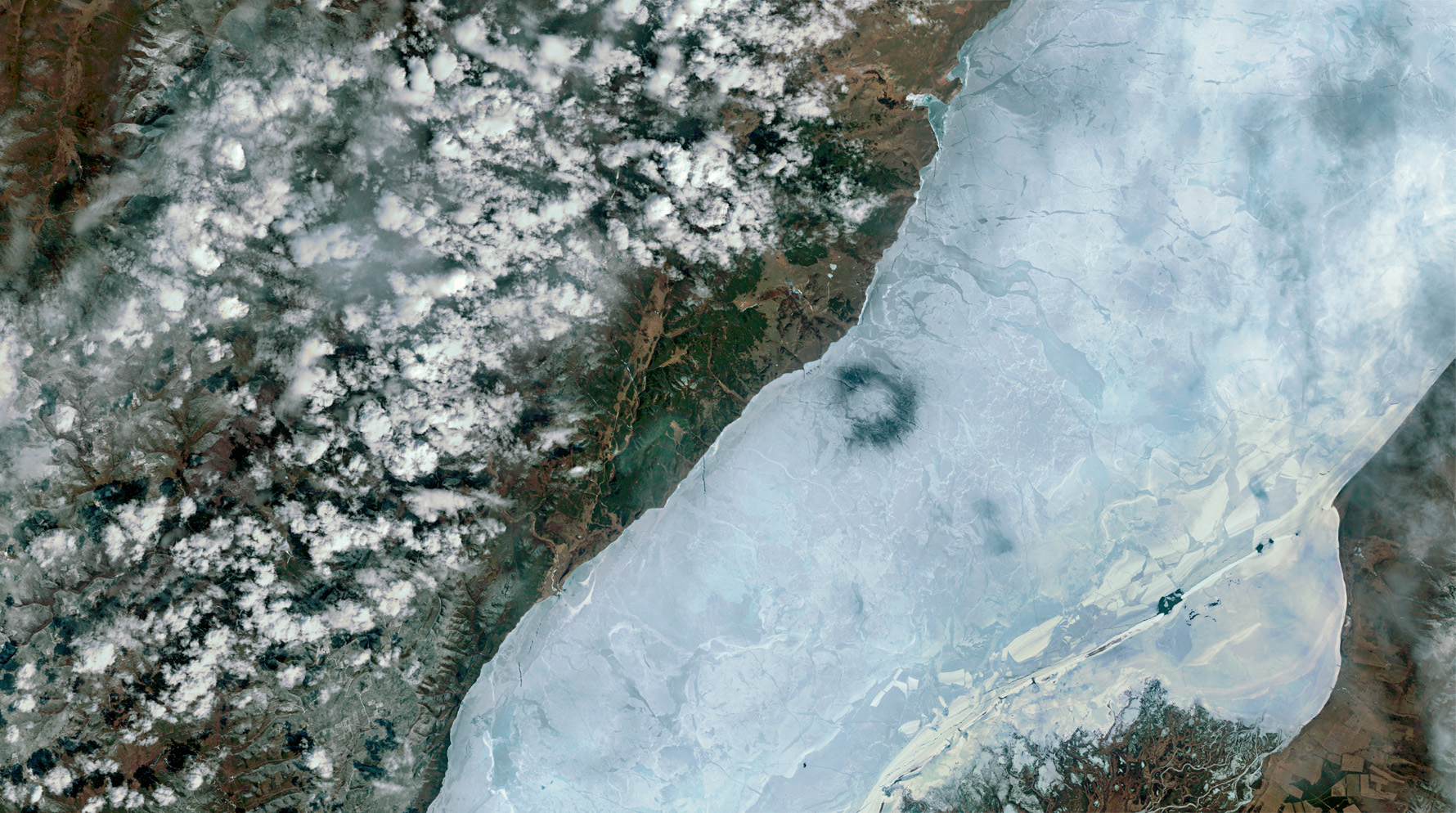

Russia’s Lake Baikal is about 25 million years old, the world’s oldest lake. It lies in a rift valley, where the Earth’s crust is pulling apart at a rate of two centimetres per year. Water fills the gap, creating a lake that is 636 kilometres long, has an average width of 48 kilometres and a maximum depth of 1,642 metres, which makes Baikal also the deepest lake in the world. It holds an astonishing one-fifth of the world’s unfrozen surface water … but this is Siberia so, in winter, its surface freezes over completely with ice up to two metres thick, strong enough to support a car.

Like any primeval lake, Baikal has its monster legends and natural oddities, but its biggest surprise is its large population of land-locked seals, one of the world’s smallest species of seal. Freshwater sub-species of Arctic ringed seals live in Finland’s Lake Saimaa and Russia’s Lake Ladoga, but it is the Baikal seal, the only separate species of freshwater seal, that has always captured people’s imagination.

British naturalist Charles Hose was one of the first to describe it for science in the early 1900s. He was on the Trans-Siberian Railway, when he stopped off at Lake Baikal. Fishermen caught three seals for him and he stored them in the luggage rack of his compartment. Two died, of course, but he dissected them, there and then, throwing soft tissues out of the train window to the consternation of the other passengers. He found them to have relatively large eyes, usually the sign of a deep diver, and larger and more powerful forelimbs and claws than most other seals, an adaptation to keep open breathing holes in the ice and for grasping prey. The biggest question, though, was how on earth did they get to Baikal in the first place?

There are several theories. Most popular is that thousands of years ago the seals came from the Arctic in the north and were cut off, but nobody really knows. What we do know is that every February their white, silky-furred offspring are born on the ice, often in dens under snowdrifts, like ringed seals. The pups emerge in spring, and wait on the ice for their mothers to return from fishing. They have to fatten up and wait until their white baby fur is shed and their grey adult coat has grown before they can hunt for themselves in the cold water. Some do not have the luxury of time.

As spring warms the lake and the ice begins to thin, a strange phenomenon occurs on Lake Baikal. Huge, perfectly shaped dark rings of thin ice form on the thawing lake. First spotted in 1999, the rings are up to 7 kilometres across and 1.3 kilometres wide, but, because of their size, they cannot be seen when standing on the ice or even from the top of nearby mountains. They are only visible from space. Using historical images from NASA and recent pictures from Urthecast’s Deimos-2 satellite, the Earth from Space team was able to examine these enormous rings and talk to scientists studying them to discover a possible explanation.

The rings have spawned their fair share of strange theories, from UFOs to shamanic ritual, and even giant bubbles of methane, but the real explanation may be more down to earth. Ice scientists believe they are created by clockwise-flowing eddies with warm water at their centre. Each year, they seem to appear at roughly the same spot in the lake, so the eddies are probably influenced by the underwater topography and water circulation. When the vortex of swirling warm water rises, it melts the ice, which thins and becomes saturated with water. It then sags and cracks, and is seen from space as a very obvious dark ring.

On the ice, it poses a serious threat to baby seals. Any in its vicinity could be in real danger of being forced into the icy water too soon, which could prove fatal. Even so, at the best of times, the lake’s youngsters have to learn to be self-sufficient very quickly. The rest of the ice breaks up by late spring, and their mothers leave them. Then they must fend for themselves. Three years on, the survivors will have pups of their own, and with 32,000 square kilometres of frozen lake to choose from, hopefully, they will find safer spots to rear them.

Canadian ecologist Jean Thie of EcoInformatics International was scanning the boreal landscape of the Birch Mountains plateau in Alberta, Canada, looking for signs of melting permafrost in wetlands. It is a key indicator of global warming that can be monitored with high-resolution satellite images, but during the survey he found something unusual.

‘When I took a virtual flight down the slopes of the plateau into the surrounding wetlands using Google Earth,’ he recalls, ‘I spotted some extraordinary beaver habitat. I had been looking for long beaver dams for several months, and here were an impressive series of dams fed by water running off the Birch Mountains. Where the wooded fen transformed into a bog, one particular large pond and dam stood out.

‘Fortunately this area is covered by high-resolution satellite imagery and so, zooming in, I could clearly see beaver lodges and channels. I couldn’t see streams or creeks flowing into the pond, but I spotted places where trees had been chewed down or killed by flooding.’

The dam itself turned out to be exceptionally long.

‘Using the Google Earth measuring tool, I found that it was 850 metres long, about 200 metres longer than the beaver dam near South Forks, Montana, which, until then had held the title of world’s longest beaver dam.’

The Canadian dam was more than twice the length of the Hoover Dam, and at one end Jean found evidence of two smaller dams, about 140 metres long, together with another beaver lodge. It means that, during the next decade or so, the large dam could grow even bigger, maybe as much as another 150 to 200 metres.

Jean checked the coordinates. The dam was located on the southern fringe of Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Alberta, a remote area of bogs and thick forest and scrub to the southwest of Lake Claire. Park rangers confirmed that they had seen large dams on aerial surveys, and this world-record dam had featured in Landsat 7 imagery, so they had an inkling of how long it had been in existence. Previous aerial photographs of the region showed that, although smaller dams had been constructed nearby, one did not exist on this site before 1980, so several generations of beavers might well have spent close to 40 years building the dam we see today.

Such an impressive dam is the work of experienced natural architects, and favoured trees include trembling aspen and white birch, which they fell by gnawing into the base of their trunks. The beavers then haul them into position or float them across the lake to shore up the dam. Once carefully in place, mud, rocks and vegetation help secure the structure.

Unlike beaver dams elsewhere in the world, which tend to be short and high and built across rivers and streams, the dams in this area are long and low. This is because the land here slopes gently and the water from mountain streams is slowed down during the spring melt, so there is a steady flow throughout the year, even during the drier times of the year, resulting in a better habitat. There were also wildfires prior to 1945 that had a major impact on the composition of the vegetation. Regeneration with poplar, aspen and birch may have attracted beavers to settle here, and their dams are often 500 metres long, although any exceeding 600 metres is rare.

The beavers build these dams for security. Once the dam is watertight, they construct a fortified lodge in the lake that forms upstream of the dam. They live on a dry platform of soil and vegetation inside, and enter and leave through underwater tunnels, usually at night. During the summer months, each lodge is like a castle, surrounded by a wide moat that keeps the beavers and their kits relatively safe from prowling bears, lynx and wolves.

The Earth from Space team began observing the record-breaking dam from satellites in 2017. At the time, it was still winter in Canada. Snow and ice locked in the dam, the frozen pond offering protection just as the water did during the other half of the year. There were no signs of activity at first, even though beavers choose not to hibernate; instead, they survive on vegetation they have stored in and around the lodge. But, as winter turned to spring, the ice started to melt and the team were keen to see how the beavers would cope with the changing seasons.

Earth from Space cameraman Justin Maguire flew in to see how they were doing, but the location is so remote that, even with a fully fuelled helicopter, he had barely 15 minutes of filming time.

‘It’s a vast landscape where everything looks the same, and then, suddenly, there’s this discernible shape … and it’s huge. I’ve filmed beaver dams before but this structure was something else, so much bigger than I’d imagined – really impressive.’

A quick survey revealed the dam to be covered by grass, with other plants growing up through the logs, and Justin could see that it looked solid and likely to hold back the spring melt water – important not only for the beavers, but also their neighbours. Ecologically, beavers are a keystone species, which means that although they may be small in numbers, they have a huge impact on their immediate environment, with many types of plants and animals partly or entirely dependent on the beaver-created wetland habitat. The dam slows the general water flow, so floods, droughts and erosion are less likely to occur, making it a more stable place to live. Where beavers have been hunted, biodiversity plummets.

During the 19th century, they were hunted almost to the edge of extinction, but now they are making a comeback, and satellites are essential in monitoring the recovery. In 1945, the area around Pakwaw Lake in Saskatchewan had no signs of beavers, but now it has been nicknamed the ‘beaver capital of Canada’. With over 20 dams per square kilometre, it may have the highest density of beavers anywhere on Earth.

‘It was my first discovery of exceptional beaver habitat,’ says Jean, and it led him to build a computer model that predicted where he might see long dams in the landscape. It was this that helped him to find the longest dam in Canada.

‘Even now, almost ten years after my observation, and having surveyed beaver landscapes in North America, Europe, Asia, and the southern part of South America, I have never seen anything like it.’

From Earth’s orbit, the Congo rainforest resembles the surface of broccoli. Millions of square kilometres of unbroken forest canopy stretches across tropical Africa; except, that is, in one spot in the Central African Republic. Here, the Earth from Space cameras focussed on an enormous clearing, a special place that hosts one of the forest’s big events – an elephant jamboree.

‘Cameraman Stuart Trowell and I were led in on foot by guides from the local Bayaka tribe,’ explains film director Paul Thompson. ‘They insist you make the 30-minute walk in silence, so they can pick up the sounds of any elephants close to the trail. The first sign that you are close to the clearing are blood-chilling roars and screams from the elephants, sounds that awaken something primeval in your brain, telling you to turn around and run the other way. The reward for ignoring that voice is a view that I can only compare to something from Jurassic Park, watching 150 elephants in one place.’

The elephants are African forest elephants, smaller in stature and much shyer than their savannah cousins, and they travel in smaller groups. They spend most of their lives hidden amongst the trees, but their regular diet of fruit, leaves and bark needs to be supplemented with minerals found in the volcanic soils. The elephants seek out clearings where these minerals can be accessed more easily. This means stepping out into the open, and meeting others of their own kind.

Elephants arriving are greeted by those already there. The matriarchs of each group seem to renew old friendships, and it is a unique opportunity for younger elephants to meet up and socialise for the very first time. The bulls, which live a lonely bachelor’s existence for the rest of the year, have other things on their mind. There are more females in the clearing than a bull may have seen in months. Testosterone levels are high, competition is fierce, and tussles unavoidable. Calves must keep their wits about them. Lifeless bodies have been found in the arena, accidental victims of the clash between rampaging bulls.

Socialising, however violent, is not the main draw of this grand get-together. There are essential minerals beneath their feet, and the families dig to find them, youngsters learning from their mothers how to drink up the mineral-rich water. Bulls uproot trees to clear the ground and churn up the mud, so the clearing gradually gets bigger after every party.

About 3,000 elephants are known to use the clearing, and when the Earth from Space team visited there were 173 elephants present on one particular day, along with rare western lowland gorillas, bongos and forest buffalo. The local people call the meeting place Dzanga Bai, or ‘village of elephants’, and it is not the only one. Satellite pictures reveal that elephants have created several clearings in the forests of the Congo Basin. The task now is to protect them. The ivory from forest elephants is harder and of a different colour to that of savannah elephants. It is known as hot or pink ivory, and it is highly prized. Ivory carvers prefer it.

It means the lives of these animals sometimes hang by a thread and, in 2013, tragedy struck at the Bai, when Sudanese poachers killed 26 African forest elephants. Since then, the WWF, ecologists and people living nearby have fought together to protect this special place and its precious inhabitants. It is now a growing centre for ecotourism, with visitors and film crews travelling from around the globe to join the elephant party.

‘I could only wonder at how many centuries this gathering has been occurring,’ reflects Paul, ‘and hope that it continues for many centuries to come.’

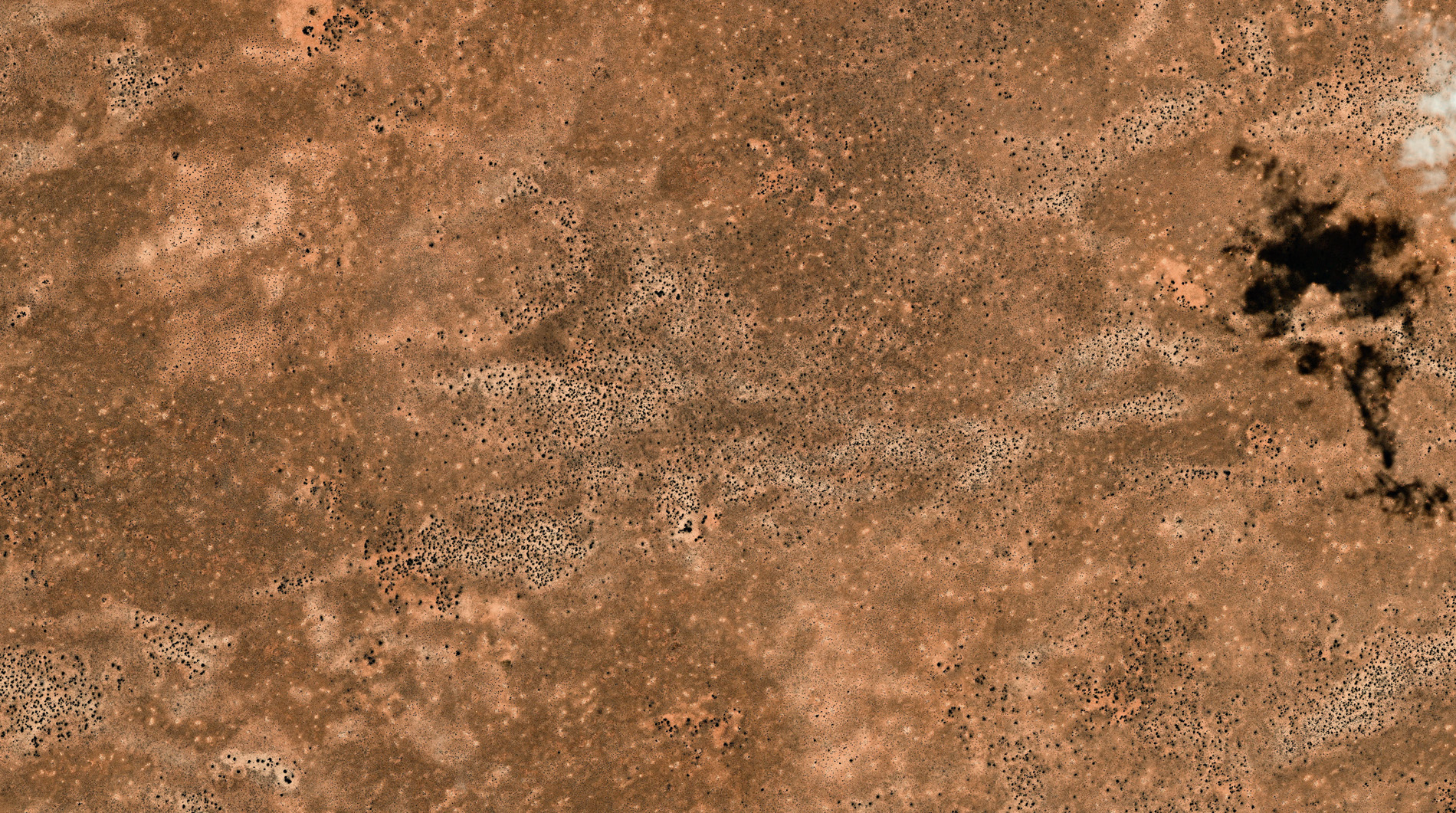

One eventful day in the Earth from Space office, the production team was looking at stunning satellite images of Uluru (Ayres Rock), when their eyes were drawn to a strange pattern. Film director Paul Thompson asked Urthecast to zoom in on South Australia, where they could see that the landscape was covered with small dark spots, spread uniformly across the ground.

‘Of course, we wanted to know what on earth they were!’

A closer look revealed them to be holes, but who was the digger? More detailed research revealed it to be a well-known Aussie resident: the southern hairy-nosed wombat. The holes are the openings to underground burrows where wombats hide to avoid the heat of the day. They only emerge when the temperature dips in late afternoon or in the cool of the early morning.

This type of wombat is more sociable than other species. It lives in large family groups with several adults sharing a warren of tunnels, with as many as 30 to 40 entrances. In most other underground species, holes like these would be escape exits, a strategy against predation, but wombats are solidly built. About 30 kilograms of solid muscle is enough to take on, say, a dingo, and the creature is faster and more nimble than it looks, so it is thought that the holes are not primarily escape routes or boltholes.

The truth is that wombats love digging. They can’t help themselves. It’s a compulsion. One animal can dig through several metres of hard soil in a night, and be responsible for over 100 holes during its lifetime, so the work of an individual and its neighbours becomes part of a larger pattern of spots that can be seen from space.

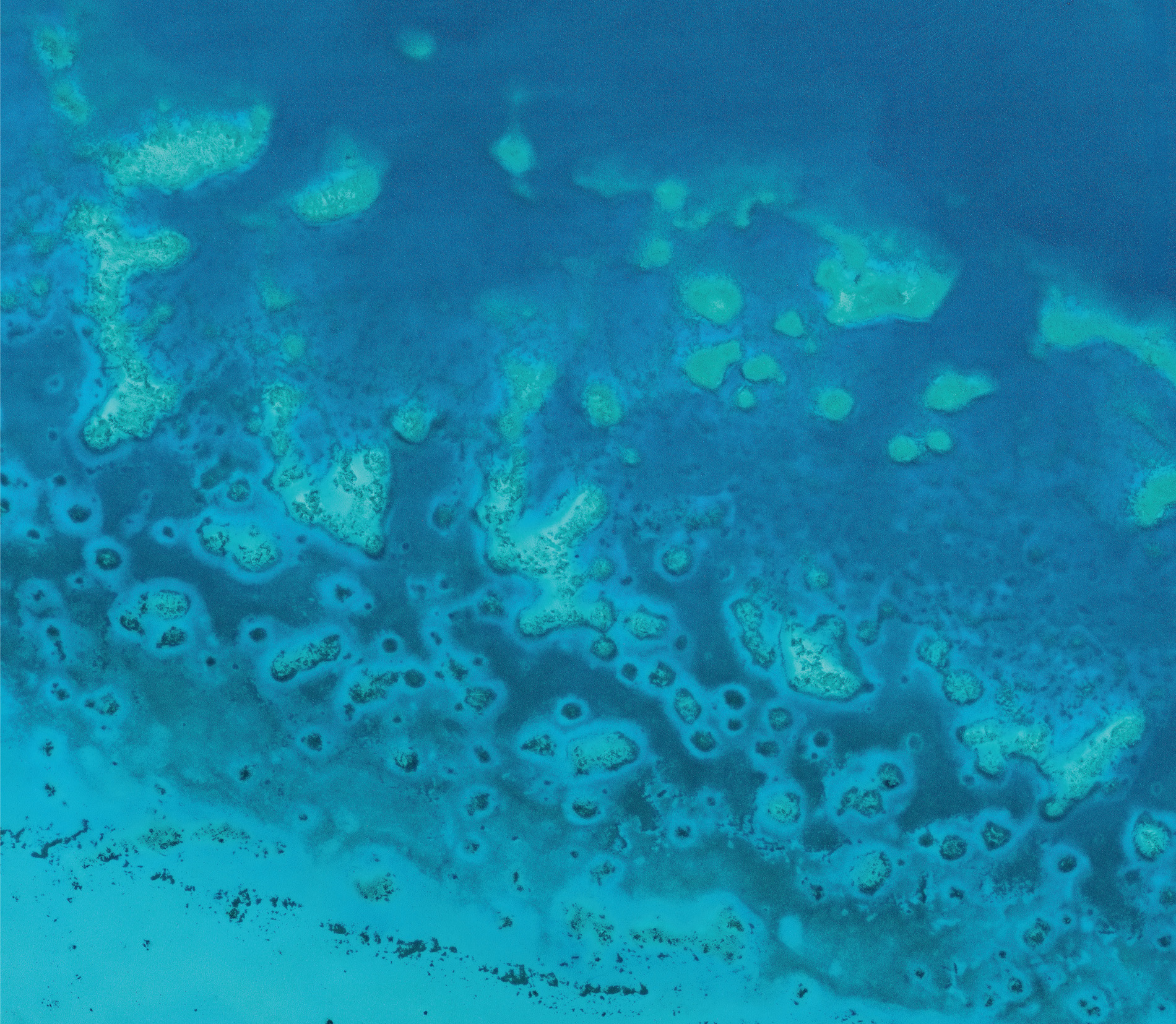

Circles are a recurrent theme when looking down on Australia. Repetitive rings of varying sizes can be spotted on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Each consists of a patch reef surrounded by a submarine meadow of filamentous seaweeds, with a clear gap of bare white sand, called a ‘halo’, between the reef and the meadow; and, the further away the seaweed is from the reef, the higher it grows.

The barren sand in the halo and the height of the seaweed is the result of fish, sea urchins or other grazers feeding close to the reef. The herbivores shelter on the reef itself, but embark on foraging excursions that radiate outwards from their central refuge. When they leave its safety, they are exposed to predators, such as sharks and groupers, so they do not venture far, generally less than nine metres from the edge of the reef, what scientists have nicknamed ‘the landscape of fear’. Their constant munching creates seaweed-free, sandy halos, and observing them is helping scientists to monitor the health of the reef.

If the top predators have been removed, say, by overfishing, the algae-eating fish, such as parrotfish and surgeonfish, make braver excursions. Predation risk is low, and so they feed further from the reef edge, causing the width of the halo of white sand to increase. If the herbivores are absent or low in numbers, the halo disappears as the algae grow back. All this can be seen from space, and so scientists can monitor the health of a tropical coral reef just by watching the size of its grazing halos increase or decrease over time.

Millions of these halo patterns appear on coral reefs all over the world, like the seagrass grazing halos off the Florida coast, and monitoring them is easier from space than on the ground. Scientists can keep watch over the world’s tropical coral reefs without ever having to enter the water … and the technique is not confined to coral reefs.

Like the patch reef halos, changes in vegetation cover in terrestrial habitats flag up the health of a ecosystem, especially the relationship between predators and prey. This can all be seen from space. It means that, again, satellites are turning out to be new tools with which we can keep a close eye on animals in the remotest and least accessible parts of the world.

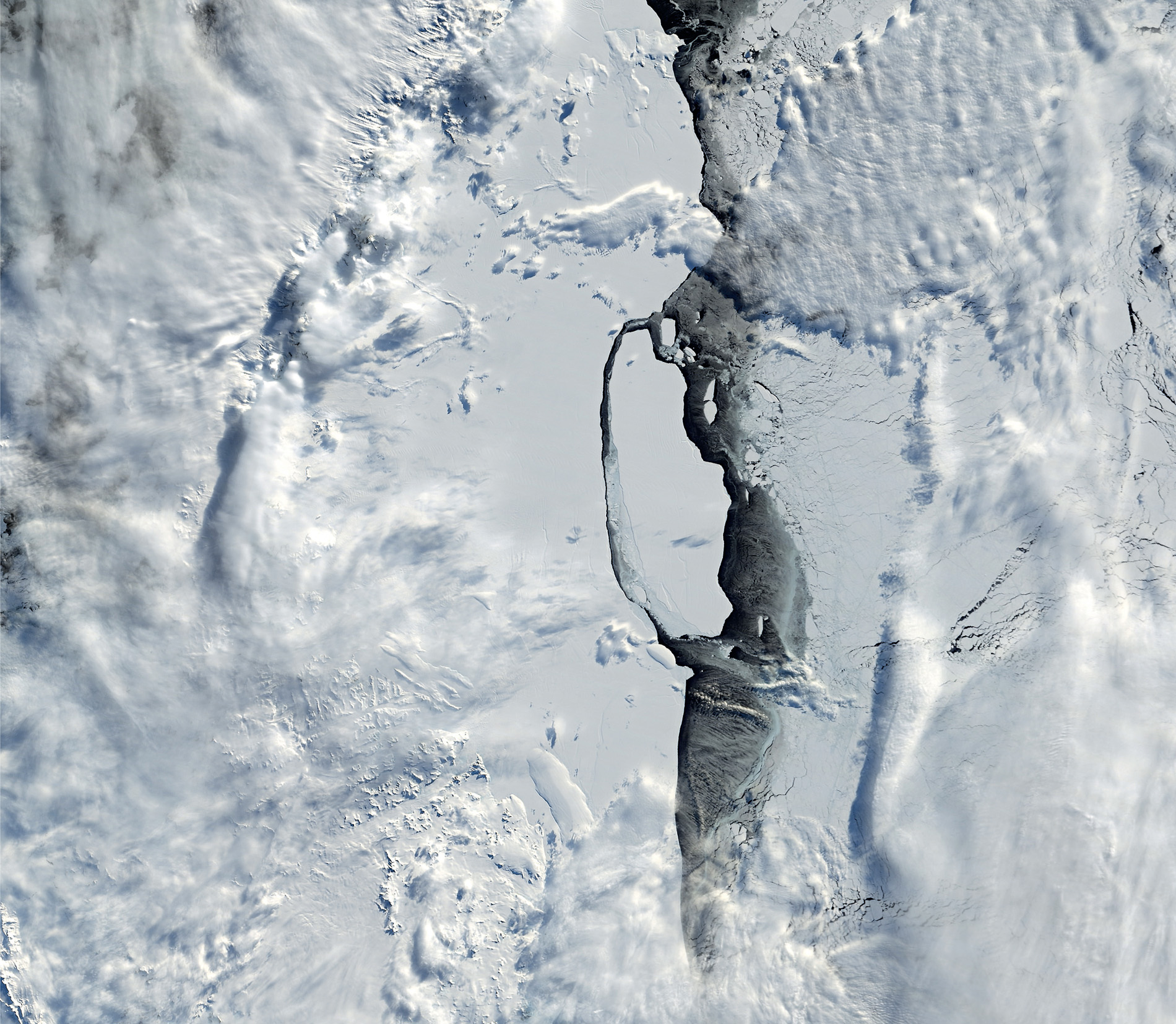

Antarctica was the last continent on Earth to be explored by humans, and even today it is difficult to reach; so much so that it was only with satellite pictures that scientists noticed an unusual pattern in the ice. It was nothing more than a very long line, but it was about to turn into something that would grab the world’s attention.

With receding glaciers and rising sea levels, the white continent is never far from the headlines, and in 2016 it was in the spotlight again. That year, scientists noticed that a major change was taking place on the Larsen C ice shelf, a thick platform of floating ice that hangs off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula bordering the Weddell Sea. They began to take a closer interest in it when the pictures showed a rift in the ice that was over 100 kilometres long and 90 metres wide. The giant crack had the potential to set loose one of the largest icebergs of modern times.

As the weeks went by, the fissure gradually lengthened and widened until this section of the ice shelf was only attached to the mainland by a short, 20-kilometre-long hinge. In July 2017, it broke free, and was named A-68.

Using high-resolution images from Urthecast’s Deimos-1 and 2 satellites, the Earth from Space production team were able to watch in detail as the crack grew and the iceberg was set loose. Icebergs break away from glaciers and ice shelves regularly, of course, without attracting international interest, but this was something else – an enormous slab of ice twice the size of Luxembourg, which weighed an estimated one trillion tonnes and, if it melts, the water released will have a volume twice that of Lake Erie, one of the Great Lakes.

While the departure of A-68 from the Antarctic will have little immediate impact on global sea levels, it does mean that the glaciers that previously discharged onto the shelf are likely to flow faster. Larsen A and part of Larsen B have broken up and gone, and if the entire Larsen C ice shelf disintegrates, and all the ice it has been holding back enters the sea, then the global sea level could rise by about ten centimetres.

Scientists are examining closely the satellite images from this region. Even though the neighbouring Antarctic Peninsula is one of the most rapidly warming parts of our planet, some researchers are at pains to point out that the calving of A-68 was part of the natural cycle of an ice shelf and not influenced, as one might think, by climate change.

Whatever the cause, an event so important in such a remote part of the world could not have been followed without satellite imagery, and, without those early pictures, we might not have known the iceberg was about to calf at all.

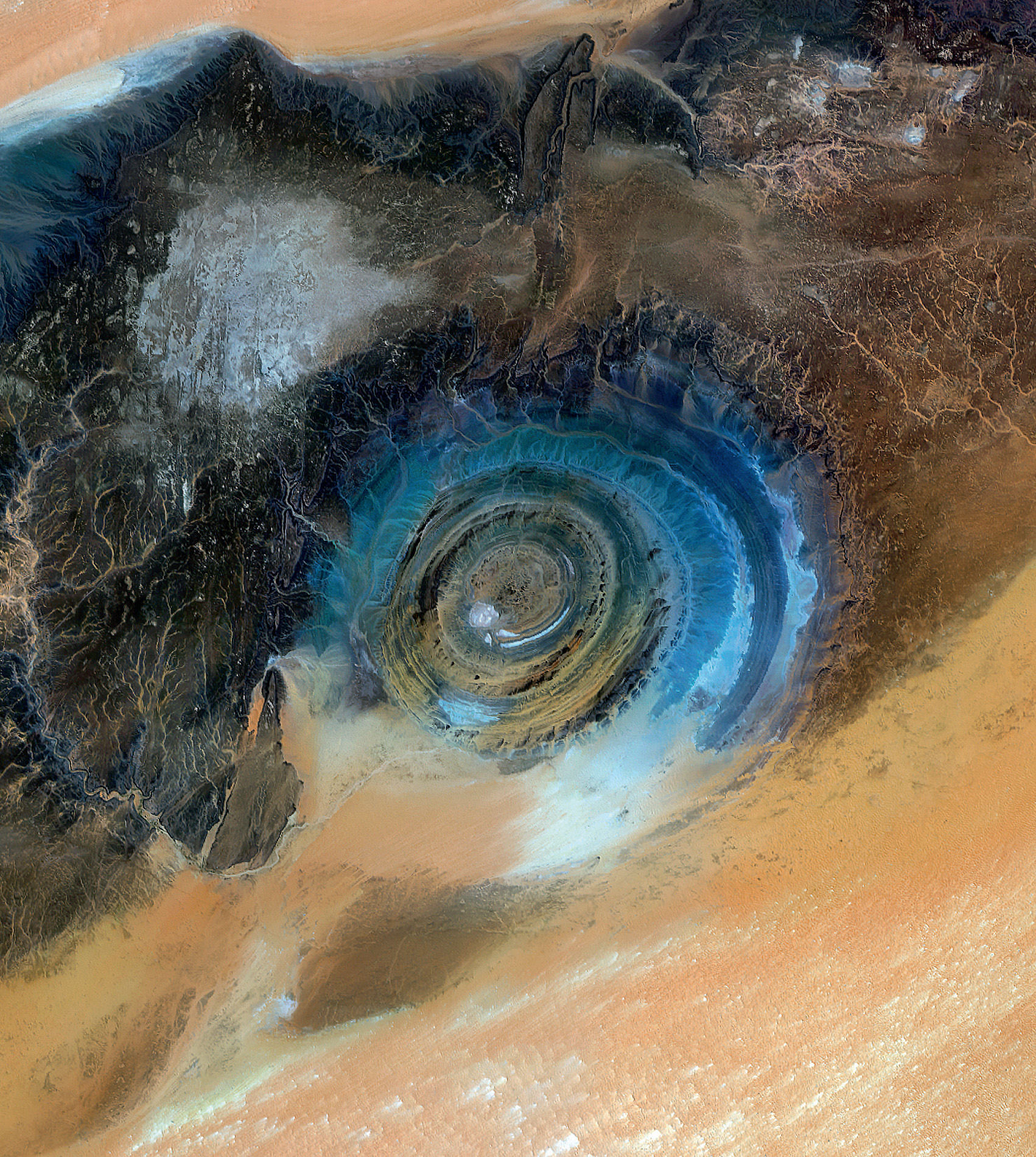

In some parts of our planet, the Earth wears its violent history on its surface, but it is only when we ventured into space and looked back that we could begin to read the story. Depending on their size, rocky bodies from outer space tend to make an impressive dent in the fabric of the Earth. In the USA, the clearly visible Meteor Crater, east of Flagstaff, Arizona, was created about 50,000 years ago when a nickel-iron meteorite, about 50 metres across, ploughed into the ground. In Canada, two circular Clearwater lakes, near Hudson Bay, are two eroded craters. Lake Manicouagan is a similar impact crater, and is clearly visible from the International Space Station, where astronauts have dubbed it ‘the eye of Quebec’. One of the most impressive features, however, must be another eye, the ‘Blue Eye of the Sahara’ or Richat Structure, as it is more formally known. But, although its shape may be similar to the others, it is probably not a crater.

The structure is hard to spot from ground level, but, when seen from a satellite, it looks like an outsized ammonite, a landmark in the featureless desert for space station crews. It is located near Ouadane in Mauritania, where it is at least 40 kilometres in diameter, and looks to all the world like an asteroid impact crater, but geologists now believe it to be an eroded, layered dome. The concentric rings are made from rocks of different ages, offering an illustrated history of the early Earth. At the centre are rocks laid down when life was getting underway, while on the outside are Ordovician sandstones over 440 million years old.

The dome itself formed about 100 million years ago, when molten rock pushed up towards the surface in an unusually symmetrical way, like a bubble. At first it failed to break through the rocks at the surface but, many years later, the dome erupted and the bubble collapsed. Erosion did the rest.

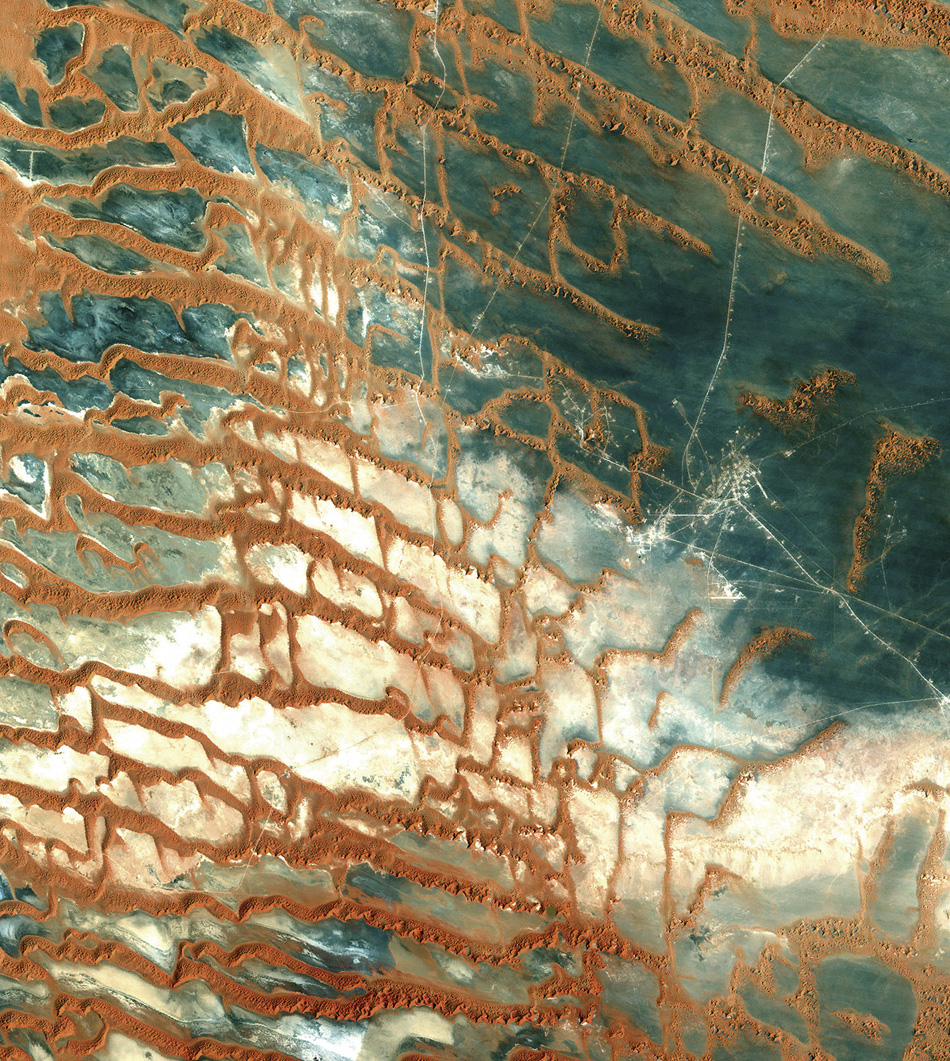

Sand dunes are Mother Nature’s kinetic art. Without vegetation to bind the sand grains, desert and seaside sands are exposed to the restless whims of the wind. At ground level it might seem chaotic, but from the perspective of space, we can see there is order. The patterns are beguiling – star dunes, crescent dunes and linear dunes – each reflecting and revealing the direction and strength of the wind. In northeast Brazil, this combination of wind, water and rock has sculpted a startling landscape.

From space, the dunes appear as a band of brilliant white that spills in from the blue of the ocean, engulfing the green of the forest. Millions of tonnes of sand have accumulated here, and every tiny grain made a similar journey. It started inland, was then washed downriver to the sea, ground up by the stormy Atlantic Ocean, washed up on the shore, and finally blown by powerful winds back onto the land. The result? About 1,500 square kilometres of brilliant white sand piled into towering dunes – the Lençóis Maranhenses, meaning the ‘bed sheets of Maranhão’.

It is a beautiful but barren and seemingly lifeless landscape. The Sun beats down from directly overhead, so there is little escape from the burning heat and the blinding sunlight reflected off the glistening white sand. The ground temperature can soar to a blistering 70°C, yet there is life here. When the Earth from Space crew on the ground arrived, they were amazed at the diversity of animals that are able to make a living in this unique landscape, and the silhouette of one of them caught their eye.

The brightly coloured, striped face, wrinkled neck and reptilian claws belong to a Maranhão slider turtle, known locally as the ‘Pininga’. It is a female and she is on a mission. With precious little water around, she has not fed for several months, but change is in the air. She is going fishing, but where is the water?

These dunes may look like a desert, but it is not one. This is Brazil, after all, with a regular rainy season, and the turtle has anticipated the coming transformation. When it rains over the dunes, the water does not drain away. Hard, impervious rock just below the sand causes it to pool in the valleys between dunes, forming hundreds of crystal clear freshwater lagoons, some up to three metres deep. Eggs, which lay dormant for several months, hatch in the pools, filling them with fish almost overnight. One fish, though, remains here all year. The wolfish rides out the dry season in damp mud, emerging at the start of the wet, and it is not the only surprise.

The female turtle heads for a flooded lagoon. While slow on the sand, she turns into a capable assassin under the water, ambushing victims that swim too close, and there are more than enough fish in this one lagoon for her to fatten up and survive another year.

When night falls, the air fills with the sounds of frogs. Members of this night chorus include four-eyed frogs. They were lying in a state of suspended animation for months, but now it is their time to mate, and for this species it is a communal affair. Dozens of males gather in the shallows and sing their hearts out, but not everyone plays by the rules. The old-timers let the youngsters wear themselves out, before letting rip.

The female frogs do not have the yellow skin pigment of the males, so there is no misunderstanding in the pool, and they are attracted to the calls of the males. The older males, who saved their energy, inevitably reach the females first, and each one hangs on tightly to his partner until the female releases her eggs. As soon as they appear, he fertilises them, and the two frogs whip up a mass of protective foam, so the developing eggs are safe from predators and that omnipresent Sun in the sky.

Mountainous areas, with their cold winters of icy winds, snow and fog, can be tough places for plants and animals to survive, but in some regions the shape of the land can bring a lifeline. At the far eastern edge of the Himalayas, the Tibetan Plateau acts as a giant heating surface that helps draw up milder air through the valleys of the Hengduan Mountains in southwest China. It enables thick forests to thrive on the high, steep slopes, creating a living space for an extremely rare animal – the black or Yunnan snub-nosed monkey, one of a genus of monkeys that have thick pink lips and an almost comical turned-up nose. It is very rare, fewer than 3,000 are thought to exist, and it is remarkable in that it lives higher than any other non-human primate.

It is a harsh place to bring up a family, but the dominant male of a group, with up to six females and a gang of adolescent youngsters in tow, needs to be savvy about how to survive up here. His group may be part of a large super-troupe or band of up to 400 individuals, and they are often on the move.

Surprisingly, when the weather turns nasty, conditions that would see most mountain animals dropping down to take advantage of more favourable conditions on the lower slopes, the snub-nosed monkeys climb up. They travel up to an altitude of 4,700 metres, sometimes above the tree line, where the solar radiation is at a maximum, their thick black fur absorbing the heat. The upper slopes are also where their main foods are to be found.

These monkeys are unusual in that they eat mainly lichens, supplemented by several other forest foods, such as frost-resistant fruits and even invertebrates. Lichens, though, take decades to regenerate, so, having exhausted one feeding site, the monkeys travel extensively to find fresh supplies. Some cover over 1,500 metres in a day, exploring a home range of up to 56 square kilometres of mainly coniferous and oak forest. They move and feed in the early morning and late afternoon, with a four-hour siesta in between.

A respite from winter’s hardships comes in spring. The young leaves on trees spice up their monotonous winter diet, and, when rhododendrons bloom, they have been seen to eat the nectar from its flowers. With frost on 280 days of the year and four to six months of snow up to a metre deep in winter, it is not an easy life. However, in this modern world, these monkeys are out of the fray as long as people do not invade their living space, hunt them illegally, and air pollution does not kill off the lichens. The area where they live is relatively inaccessible to people and includes some of the most biologically diverse parts of China. Even so, many large mammals have been wiped out in the area and the black snub-nosed monkey is still one of China’s most endangered primate species.

Asia’s longest river and the third longest in the world, the Yangtze, passes through deep gorges in Yunnan province. It has its headwaters in the snow-covered Tanggula Mountains on the Tibetan Plateau and, from space, the river looks at first to be a long silver ribbon, then mottled green and brown with silt and sediments, and finally pink with industrial pollution that spews into the turquoise waters of the East China Sea.

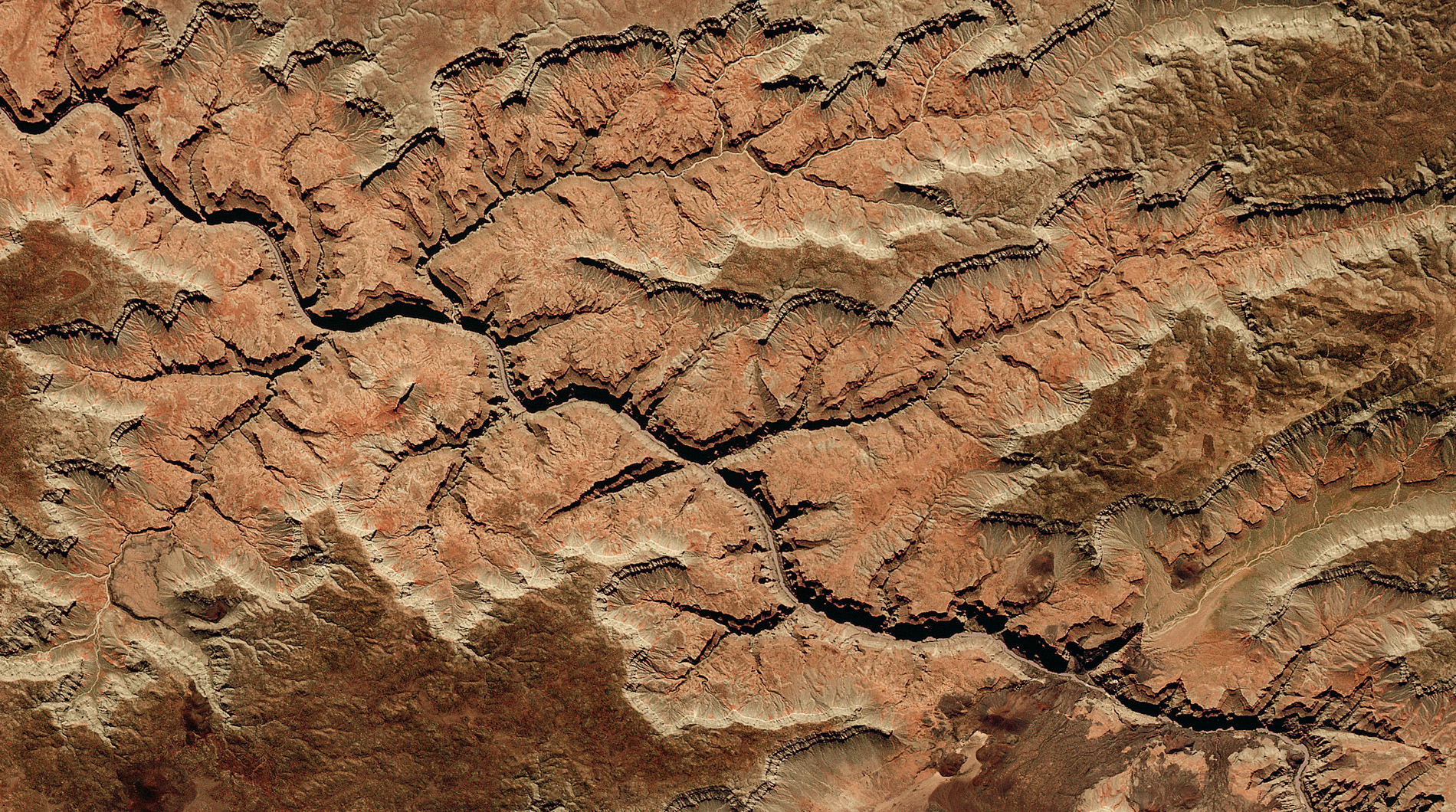

As rivers follow their journey from source to mouth, the water rides the unique contours of the landscape and reacts with the rocks and earth beneath, giving each waterway its own personality. The Brahmaputra, for example, has sliced through the rocks of the eastern Himalayas, and, together with an uplifting of the land, forms the Yarlung Tsangpo Canyon. At six kilometres deep, it is the deepest canyon in the world, far deeper than North America’s Grand Canyon. Other rivers erode the soft rocks but tumble over hard rocks in spectacular waterfalls, like those at Iguaçu, Niagara or Iceland’s Dettifoss – the most powerful waterfall in Europe.

Where the land is flatter, rivers zigzag towards the sea, and, the greater the amount of sediment they carry, the more likely they are to meander. There are also rivers that fan out, forking again and again to create hundreds of shape-shifting ephemeral islands and multiple channels. In Iceland, ‘braided rivers’ flow over open volcanic plains, picking up enormous loads of ash that builds into networks of river channels separated by temporary islands or braid bars. Wherever these rivers flow and whatever their ‘personality’, they are sure to bring life; none more so than the world’s largest river system – the mighty Amazon.

One-fifth of all the world’s river water flows down the Amazon. From its source in the Peruvian Andes to its mouth over 6,000 kilometres downstream, on average over 200,000 cubic metres of water pour into the Atlantic Ocean every second. It is more than the total discharge of the next six largest rivers combined, and its area of influence is huge. The main river and its tributaries drain 7,000,000 square kilometres of South America, the largest drainage basin on the planet, of which 6,000,000 square kilometres is tropical rainforest.

Seen from space, the network of rivers and streams can be seen winding their way across this vast area but, for much of their journey, they do not rush. At Iquitos in Peru, the Amazon is only 100 metres higher than at its mouth, the gradient being a drop of little more than two centimetres for every kilometre until the confluence with the Rio Negro, and thereafter just one centimetre per kilometre. This allows the Amazon to take its time, meandering through flooded forests and wetlands, following the path of least resistance and creating beautiful sinuous patterns when viewed from above.

Using NASA satellite imagery from 1984 to 2017, the Earth from Space team was able to build a timelapse video sequence. It reveals how the route taken by the water is not fixed, but the many tributaries to the main river change their paths as they snake through the Amazon Basin. One result of this ever-changing pattern is that the Amazon forms more of one distinctive shape that any other river on Earth. From space it is as if hundreds of horseshoes appear and disappear, each one an oxbow lake.

An oxbow is a bend in the river that has been cut off from the main flow. It can be small, just a few metres long, or enormous and several kilometres long. Whatever the size, it is a magnet for wildlife, because it has all the benefits of the river without having to constantly fight against the energy-sapping flow. It is the perfect place for giant river otter parents to raise a family, or a pod of Amazon pink river dolphins to feed. It can also be a special place for people.

Elvira is nine years old. She lives in a small community in the Peruvian Amazon. She and her friends like to explore the forest on their doorstep, but her favourite place is a little further into the jungle.

‘I always look forward to going there,’ she says. ‘It’s a magical place.’

Known to the local people as El Dorado, this special place is a huge oxbow lake, clearly visible from space.

‘The lake is the very best place for seeing lots of different animals,’ says Elvira. ‘I’ve seen river dolphins, turtles, fish and many different birds, too many to name.’

While the Earth from Space film crew was there, Elvira was about to add another animal to her list.

‘They’re coming from so far away,’ she exclaims. ‘I hope they are safe, and get here OK.’

And, to spot the new arrival, she listens carefully.

‘I can hear it,’ she cries. ‘There it is!’

An aircraft comes into view, its precious cargo closely guarded. It is a floatplane and it lands on the river, its cargo is unloaded.

‘Let’s go, let’s see.’

Elvira pushes to the front of the crowd.

‘I want a closer look.’

It’s an Amazonian manatee, a close relative of the gentle animals that ancient mariners once mistook for mermaids. This is one of five brought here to start a new life in the safety of the oxbow lake. They are the largest mammals in the Amazon but, despite their size, they are rarely seen. They feed on aquatic vegetation, only surfacing to breathe once every five minutes or so. They are easy targets for hunters, who kill them for their meat, but these are the lucky few that have been rescued and rehabilitated. For Elvira, it is a chance to get a really good look at a creature that is usually hidden.

‘You might live your whole life here and never see one, so it’s amazing to be able to be so close.’

One of the manatees was found at a village nearby, but now it is to be released back into the wild, and Elvira is about to play a leading role.

‘On the count of three,’ a voice shouts. ‘One, two, three.’

And Elvira helps ease the manatee into the water.

‘Hopefully they’ll be safe and happy here at El Dorado. I’ll try and visit them, and maybe there will be more manatees here in the future.’

Elvira’s optimism is welcome. There are thought to be no more than 30,000 of these animals in the entire Amazon river system, according to IUCN, but nobody is certain because the river water is so murky and the animals so difficult to spot. The trend, however, appears to be downwards. Faced with increased boat traffic, drowning in fishing nets, oil spills, habitat loss, climate change, reduction of vegetation in waterways, and illegal hunting, Elvira’s manatee is an important individual in the fight to save this shy and secretive species.

When our ancient ancestors first abandoned a nomadic lifestyle, stopped relying on hunting and gathering, and put down roots to farm domesticated animals and grow crops, those first farmers inevitably settled close to a waterway. It caught on. Even today, most of our major cities – London, Paris, New York – are beside rivers. Water, after all, is vital to keep us healthy. It’s also essential to quench the thirst of all those animals and to grow all those crops; at least as long as you could get the water to them. If you could not rely on sufficient rain, a bucket was probably the first solution, but the scale was wrong. Then one enterprising soul had a brilliant idea. You can’t bring crops to the river, they thought, but you can bring the river to the crops, and irrigation was born. Now, irrigation, along with different methods of farming, is responsible for some of the most striking man-made patterns on the face of the Earth.

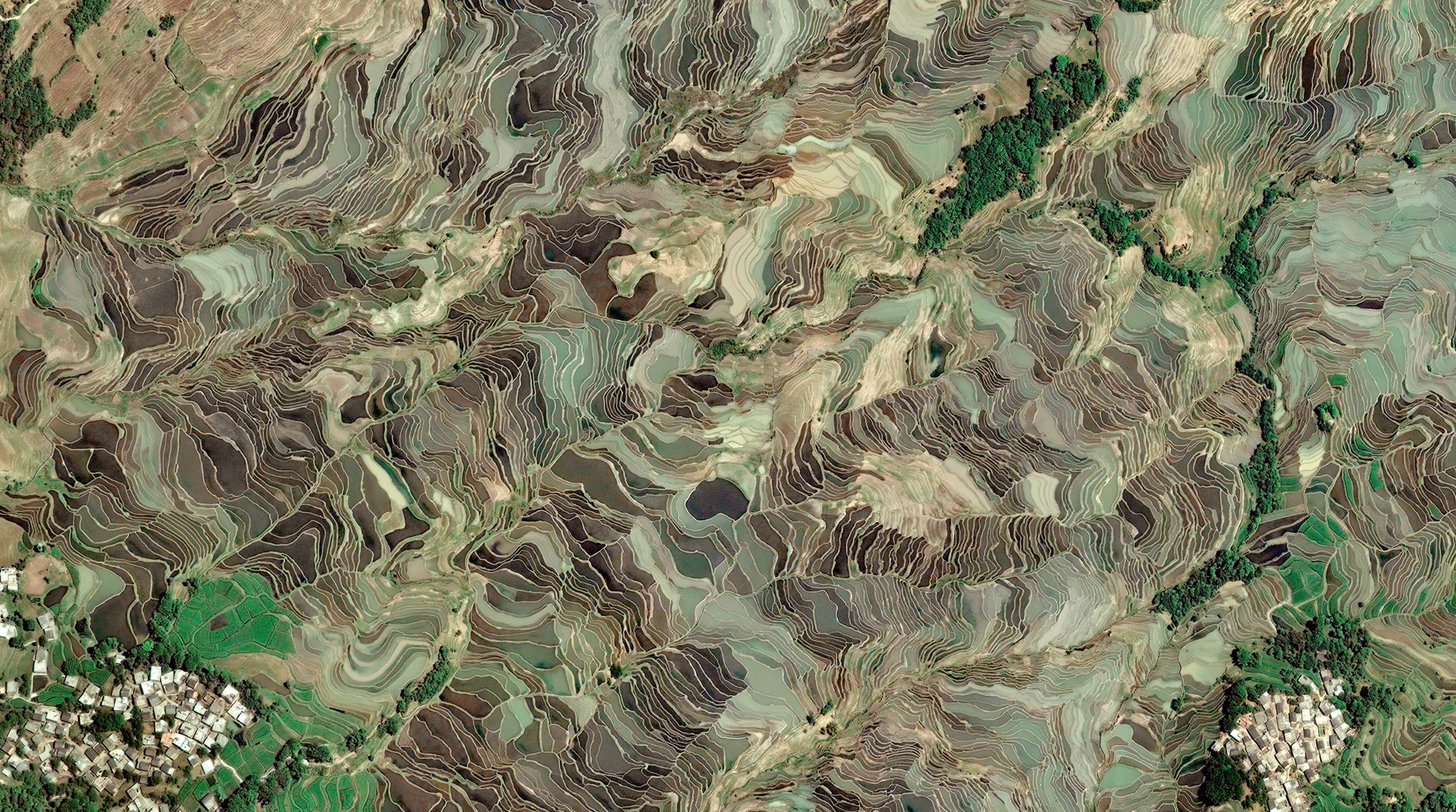

In Brittany, an irregular patchwork of small fields harks back to land use in the Middle Ages. In Minnesota, large square fields reflect the way early 19th-century farmers made best use of their new farm machinery. In Bolivia, fields have a radial pattern. Each has a small community at its centre, which is surrounded by fields set out like the spokes of a wheel. In Thailand and China, thin strips of rice terraces are fed by irrigation canals and follow the contours of the hills and, similarly, the tightly packed slender fields in Sudan are separated by man-made channels. Look from space at the USA, however, and you will see the most impressive pattern of all: thousands of circles covering the Mid-West like a patchwork quilt.

Variegated green and yellow circles appear where a single moving and rotating arm of water sprinklers irrigates circular patches of crops. The different colours are due to crops being at different stages of growth. However, no matter how tightly they are packed, there are always gaps in between, and the bigger the circles, the bigger the gaps. Conservationists are putting them to good use.

The bobwhite quail is one of the New World quails, only distantly related to the more familiar Old World quails, and, all across North America, populations have been thinning due to disappearing habitat, down by as much as 80 percent in some places. To help reverse the trend, the National Bobwhite Conservation Initiative has been encouraging farmers to plant native grasses and forbs in the triangles between irrigated crop circles as a habitat for quail. Already, quail populations are beginning to bounce back. America’s farmers really are making a difference.