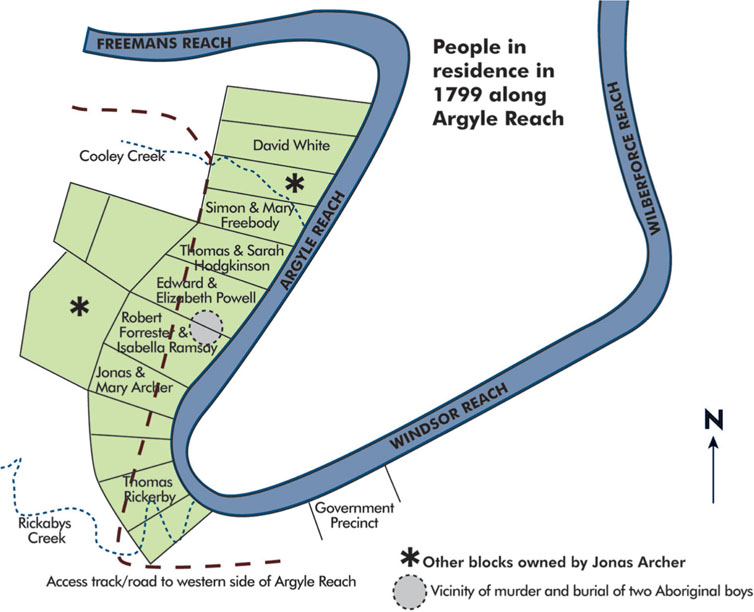

2 The Argyle Reach Settlers

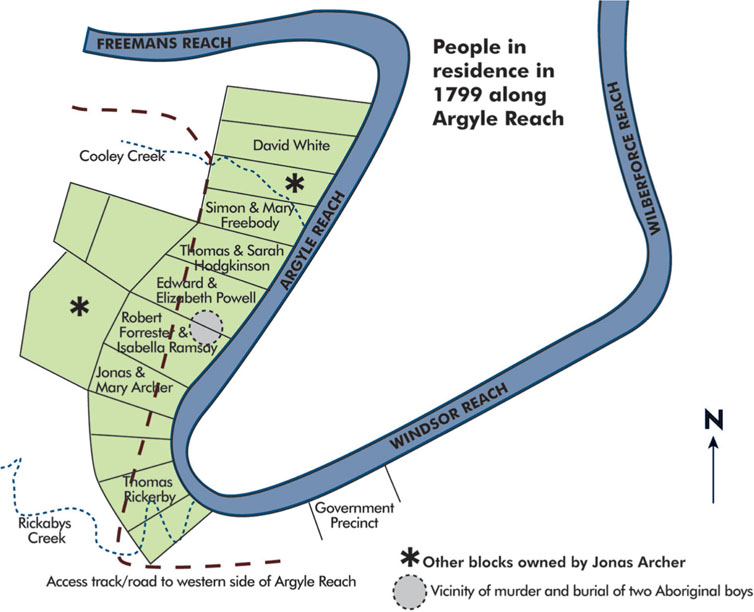

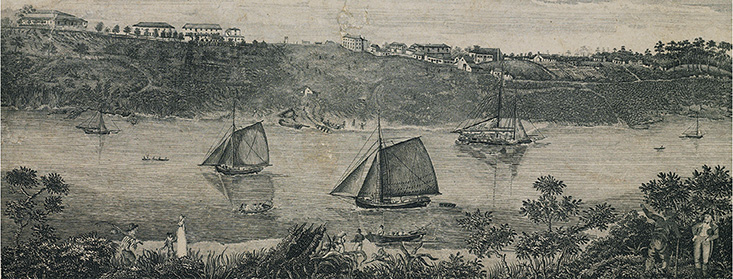

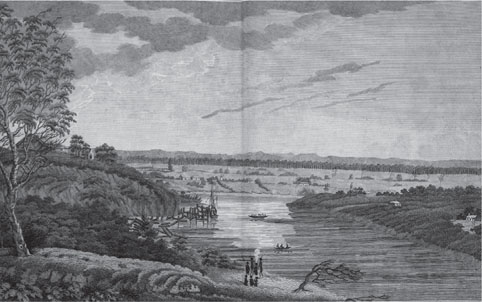

The bodies of Jemmy and Little George were buried in a shallow grave, the location of which was described by Chief Constable Thomas Rickerby when he gave his deposition. The site was about eleven rods from the houses of Edward Powell and Isabella Ramsay. Eleven rods equates to roughly fifty-five metres. The house sites can be seen from a watercolour of the Argyle Reach painted a few years later (see page 24). The artist, John Lewin, was obviously impressed by the beauty and serenity of the location. Hawkesbury historian Jan Barkley-Jack has identified Isabella Ramsay’s house as the one to the right of the ploughed land and Powell’s house with the silos next door.1

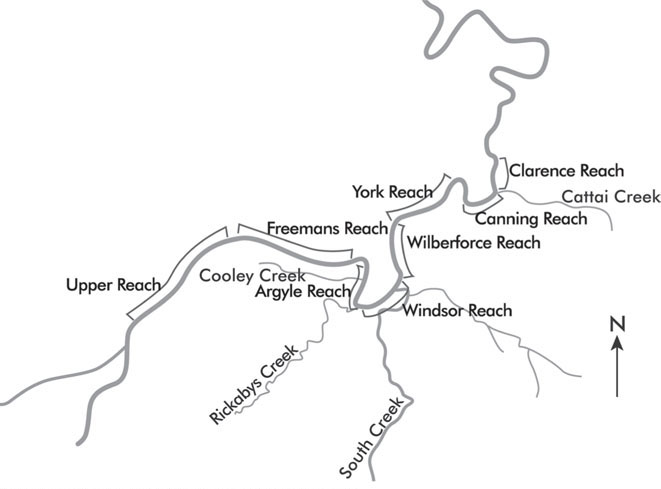

The Argyle Reach of the Hawkesbury River starts a few hundred metres west of the oldest part of the town of Windsor. The old town centre sits on a high riverbank overlooking the river, 120 kilometres by boat from the river’s mouth. Where Windsor’s oldest buildings stand is more or less where, in 1799, Lieutenant Thomas Hobby of the New South Wales Corps was stationed with his detachment of soldiers. Windsor did not officially become a town until Governor Macquarie declared it so in 1810.

Farming began on the Argyle Reach in 1794, five years before the two Aboriginal teenaged boys were murdered there. The colonists who first tilled those fertile banks were a long way from any protection a township might have offered. Soldiers stationed in Parramatta were about 30 kilometres away and Sydney was another 23 kilometres further on. The Hawkesbury farming settlement was a full day’s walk to Parramatta or several days boat journey down the river, out to the ocean and down the coast to reach Port Jackson and Sydney. The first settlers on the Argyle Reach camped on their own grants of land rather than forming up into a village and walking out to work. In the first year of settlement on the upper reaches of the Hawkesbury River (the location named by the colonial authorities as Mulgrave Place), there were perhaps 118 parcels of land granted. They were granted predominantly to ex-convicts. But 33 were to soldiers who could not possibly occupy the grants at that time. Each parcel was usually 30 acres in size although the soldiers’ parcels were usually 25 acres.2 Five grants were to free settlers who were already, or about to be, discharged from navy or army service.3 For many it was farming for the first time in their lives although some had already tried farming around the Parramatta district or on Norfolk Island.

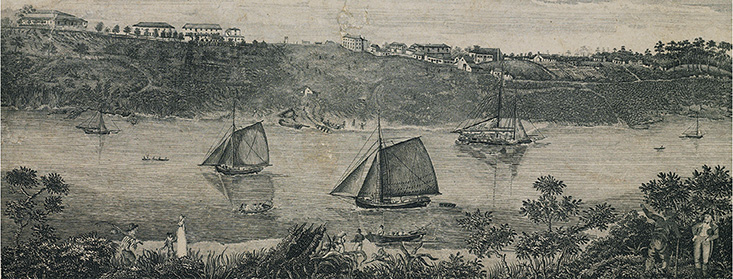

This view of the Argyle Reach shows Ross Farm (with ploughed field) owned in 1799 by Jonas Archer, Forrester’s Farm (next on the right) where the two Aboriginal boys were interrogated, and Doyle’s Farm (owned in 1799 by Edward Powell) the next on the right with two silos by the house. Watercolour by John Lewin painted between 1805 and 1812, courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

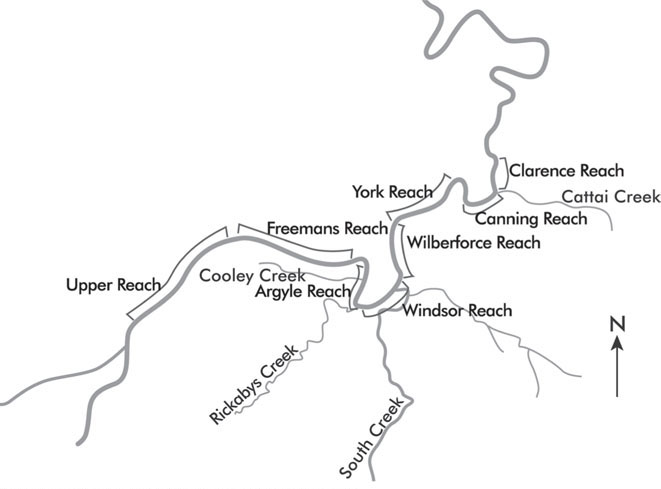

The grants were along both sides of the river covering those sections that became known as the Windsor Reach, the Argyle Reach and South Creek. Shorter sections of York Reach, Wilberforce Reach and Upper Reach (closer to present day Richmond) were also surveyed and allotted. The grantees were men given what had been promised—land grants to own and work for their own benefit. The paperwork proving land tenure was often missing for those first settlers. It was a problem left by the acting governor, Major Francis Grose, when he left the colony. Governor Hunter had to make a new list of those who had received land grants when he took over from Grose’s temporary replacement, Captain William Paterson. The Hawkesbury land grants were something special for these settlers—they could never have aspired to land ownership back in Britain. This was good agricultural soil on a fertile flood plain and it quickly showed how readily it responded to cultivation and cropping.

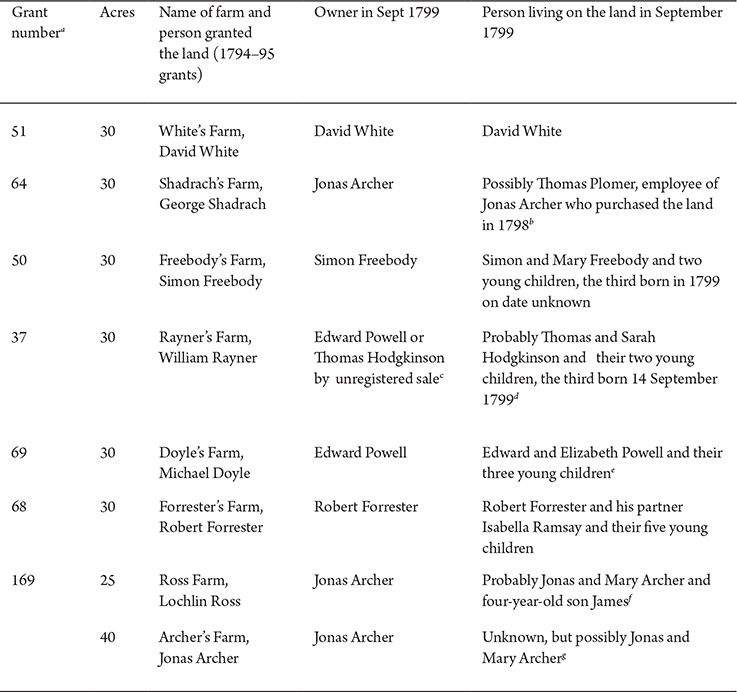

The map on page 28 shows the layout of the Argyle Reach grants and the general vicinity where Jemmy and Little George were buried. Table 1 shows who was in possession of each farm along the western riverbank in August 1799. Table 2 shows, as far as the trial and deposition records indicate, the farm owners and their labourers employed on each farm.

Aerial photograph of the Hawkesbury River in the vicinity of Windsor. Land and Property Information. Penrith Run 3, Print 100, NSW4941 dated 20/12/2005. Source: © LPI – NSW Department of Finance and Services [2014]. Panorama Avenue, Bathurst 2795. www.lpi.nsw.gov.au

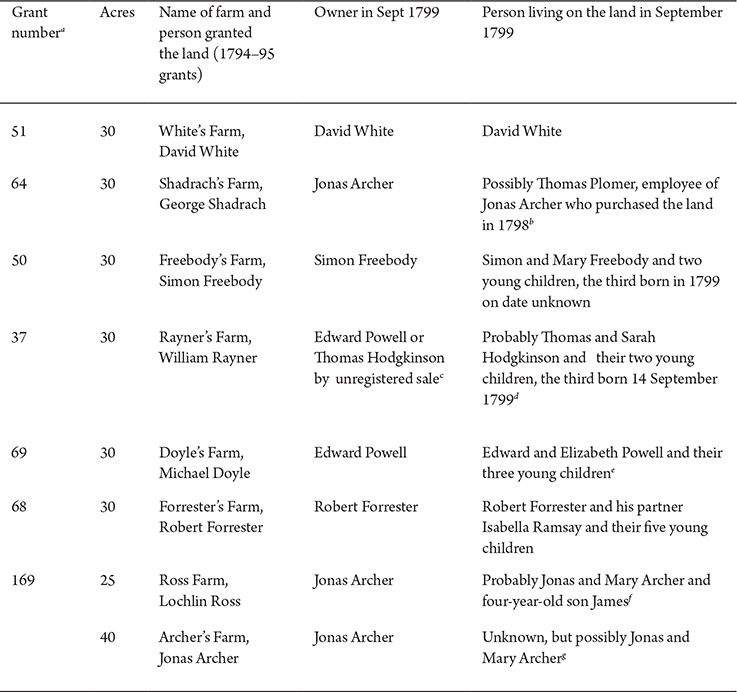

Table 1 Land Ownership and Residents on the Argyle Reach in August 1799

a These numbers indicate the consecutive position of the grant in the Land Grant Register that lists all land grants in the colony. The grant numbers are reproduced in Barkley-Jack p. 110.

b Barkley-Jack pp. 286, 342.

c Barkley-Jack, p. 165. Powell purchased 60 acres from ex-convicts Michael Doyle and William Rayner on Argyle Reach.

d Old Register Book 1 p. 4, Entry 6 dated 11 September 1822. Twenty acres of Rayner Farm, indentured to Thomas Upton by Thomas Hoskisson. This is probably Sarah Hodgkinson’s son Thomas promising part of the property to his mother’s second husband, Thomas Upton.

e Doyle granted 30 acres 3 December 1794 and was in possession in October 1794. Powell’s purchase of the farm from Michael Doyle registered as 24 February 1798.

f Purchased probably 1795 but sale registered 1798. Barkley-Jack p. 423.

g Grant by Governor Hunter to Archer registered 1800.

Table 2 Settlers and Farm Labourers on Argyle Reach at the Time of the Murders

(Four of the five defendants in the trial are identified in bold. Some of the witnesses for the prosecution are identified in italics)

|

Settlers

|

Farm labourers employed

|

Note

|

|

Jonas Archer and Mary Archer

|

John Pearson

|

Pearson usually slept at

|

| Robert Forrester and Isabella Ramsay |

James Metcalfe |

|

| Edward Powell and Elizabeth Powell |

Thomas Sambourne. Possibly also Bishop Thompson. |

|

| Thomas Hodgkinson (killed by Aborigines) and Sarah Hodgkinson |

William Timms |

|

| Simon Freebody and Mary |

Unknown |

|

| Freebody |

|

|

|

David White

|

Unknown

|

|

Four of the five defendants in the trial are identified in Table 2 as Argyle Reach settlers or employed labourers. William Butler, the fifth defendant in the trial, was share farming at the Hawkesbury. His farm was possibly on the Argyle Reach but the location is, as yet, unidentified. Butler arrived in New South Wales on the First Fleet ship Scarborough and by 1791 he was ‘free by servitude’. In that same year, at age 23, he married 17-year-old Jane Forbes who had arrived in the colony one year earlier as a convict on the Lady Juliana. Together they had a daughter and then a son but Jane died in 1795 in an unfortunate accident when she fell into a kitchen fire. In September 1799 William Butler was a 31-year-old widower with his young children probably still in his care.4

Starting from the second farm at the northern end of Argyle Reach, David White was in occupancy. In September 1799 he was 33 years old, living in a house on the farm, probably alone or with an employed or assigned (convict) worker. He had been under suspicion for stealing. His neighbour four farms down Argyle Reach, Edward Powell, in the capacity of local constable, had searched David White’s house several times for stolen goods. Powell had apparently also had cause, more than once, to take him into custody.5

The land grants along the western side of Argyle Reach showing the persons in residence when the two Aboriginal boys were murdered.

The next farm, known as Shadrack’s Farm, belonged to Jonas Archer who had at first rented then purchased it from George Shadrack. When land grants were recorded the name of a farm generally began as, and continued with, the name of the original grantee. So George Shadrack’s grant of 30 acres was known as Shadrack’s Farm, even after ownership changed. Aborigines attacked Shadrack and his government servant, Akers, in 1795 leaving Shadrack severely wounded. Archer probably took over the farm following Shadrack’s inability to continue. The sale of Shadrack’s Farm was not registered until 1 January 1798 although Archer probably took possession earlier.6 In July 1799 a man named Thomas Plomer was in charge of guarding Archer’s wheat crop on this farm. Archer had employed Plomer since April that year to protect the crops from straying pigs and horses.7

On the southern side of Shadrack’s Farm was Freebody’s Farm. Simon Freebody was another 1794 ex-convict grantee. Like David White two farms upstream, he had stayed the course to farm his grant. Freebody arrived in the colony on the Surprise in 1790 with a seven-year sentence given at the Old Bailey for stealing a lamb carcass from a slaughterhouse, a sentence that would have expired by the time he received his land grant. A marriage ceremony is also unrecorded for Simon and his wife Mary Wells. Mary’s seven-year sentence also would have expired by 1799 as she had arrived in New South Wales seven years before on the Royal Admiral. By September 1799 Mary and Simon were both aged around 32 years. They had a family of two daughters and one son: Ann, a toddler of two years; Sarah, a one-year-old baby; and Simon (junior) was born sometime during that same year.8

The next farm along, known as Rayner’s Farm, was home to more small children. Very probably it was the young Hodgkinson family in occupancy. This farm had been granted to William Rayner in 1794 and he worked it for at least two years, perhaps longer. The ownership of Rayners Farm in 1799 is uncertain. It could possibly have been neighbour Edward Powell although there is no record of transfer from William Rayner. But in September 1799 it was Thomas Hodgkinson (Hosskisson) and his wife Sarah and their young children who were most probably living there. Sarah had arrived in the colony in 1791 as Sarah Pigg. The couple married in 1795 and although Sarah had received a life sentence, she and her husband would have celebrated the absolute pardon she was granted in the June of 1798. Her husband was also free having served out his seven-year sentence.a Their first child, Mary, was born in late 1795, and a son, young Thomas, was born two years later. Sarah, probably in her late twenties, was again pregnant when Aborigines killed her husband in August 1799. The baby was born on 14 September 1799, just four days before the two Aboriginal boys were murdered.9

Next to Rayner’s Farm, Edward Powell and his wife Elizabeth, known as Betty, lived on Doyle’s Farm. Both had arrived in New South Wales in 1793 as free settlers on the Bellona. They married just eight days later and were soon clearing a land grant at Liberty Plains, about halfway between Sydney and Parramatta. But that area proved fairly unproductive to both wheat and maize cropping. They continued to live at Liberty Plains until February 1798 when Powell purchased Doyle’s Farm.10 In September of 1799 Edward was 37 years old and Betty 25. They already had three young children: five-year-old Sarah, Mary aged three and young Edward who was turning just one that month.

We know more of Edward Powell because he had already been to New South Wales before he returned as an immigrant settler. He had been a seaman on the Lady Juliana, the notorious ‘floating brothel’ of the Second Fleet. He seems to have taken his relationship with a convict passenger perhaps more responsibly than many others. The baby born to young Sarah Dorset was christened Edward Dorset Powell when the Lady Juliana arrived in Sydney. Although Powell and several seamen who had also formed attachments with convict women desired to stay in Sydney they were not allowed to do so. Required as crew on the homeward voyage, Powell returned to England while Sarah Dorset was sent, with her son, to Norfolk Island, there to serve out the rest of her sentence. Perhaps Powell was returning to Sydney on the Bellona to reunite with Sarah and their son, but if it was the plan it did not happen. Instead he and Betty Fish married eight days after the Bellona arrived. Within a month they were granted land alongside the Rose family at Liberty Plains. Thomas Rose was Betty’s uncle. He and his immediate family, including their niece Betty Fish, and another young women from the same town in Dorset, had answered the call for free settlers to New South Wales. Betty Fish, like Edward Powell, at the time of their marriage had already parented a child. When Betty boarded the Bellona in July 1792 she held a one-year-old baby in her arms. Tragically the baby died of ‘worm fever’ just ten days after they sailed.11

Once at the Hawkesbury, Powell took on the government job of civilian constable along with two or perhaps three other settlers. They were all under the command of the senior constable, Thomas Rickerby. Constables were elected annually by the local landholders and appointed by the governor. They had to be literate as their duties included assisting in musters and other information-gathering such as periodically listing all people working on the local farms. Under orders from the chief constable they were often busy and away from their own farms, investigating complaints, keeping the peace, or transferring prisoners from the Hawkesbury to Parramatta. Powell’s job allowed the family another assigned servant to add to the one he was already allowed. The extra pair of hands were likely to be another man to work on the farm but could equally have been a woman to help domestically, especially with the day-to-day needs of a young family.

The Forresters, a couple with five children, lived on the next farm. Their farmland was allocated to Robert Forrester as one of the early 1794 grants. Arriving in New South Wales with the First Fleet he had served out the last few years of his seven-year sentence in Sydney during those harsh years of food shortages. In 1791 he selected a Third Fleet convict, Mary Frost, for a wife but the marriage did not last. He received a grant on Norfolk Island but returned to Sydney after eighteen months. A few months later he formed a de facto relationship with Isabella Ramsay, another Third Fleet convict serving a seven-year sentence for theft. In September of 1799 Isabella was living in the house on Forrester’s Farm with Robert and their children: Elizabeth aged five, Margaret four, Robert three, John aged two and Henry who was born in March that year. Robert Forrester was then aged around 40 years and Isabella Ramsay, known as Bella, was approximately 25 years old.12

Neighbouring Forrester’s Farm were the 25 acres known as Ross Farm. It was a 1795 grant to soldier Lochlin Ross but was purchased in 1798 by Jonas Archer.13 The same year he purchased Shadrach’s Farm further down the reach.14 Archer also secured the 40 acres adjoining Ross Farm by grant from Governor Hunter.15 That property, known as Archer’s Farm, lay behind both Ross Farm and Forrester’s Farm. Born in Manchester, Jonas Archer arrived in the colony on the Atlantic in 1791. His partner, Mary Kearns, arrived from Ireland two years later on the Sugar Cane and she took Archer’s name when she started living with him. The Archer family included a four-year-old son, James, born before they moved to the Hawkesbury. Together were very successful in farming and probably trading, also at the Hawkesbury.16 In September 1799, at the time of the murders, the Archers were ‘free by servitude’ and were the most successful farmers on the Argyle Reach, having three properties under cultivation. They were probably living on the riverside Ross Farm when Mary Archer reported the murder of the two Aboriginal boys to Chief Constable Thomas Rickerby.bFarmhouses on the Argyle Reach were situated 50 or more yards back from the river. Watercolour sketches around 1805 indicate most as being simple thatched huts of perhaps two rooms with a chimneystack at one end or in a skillion (a lean-to room on the side). Walls were either wattle and daub or wide timber boards attached horizontally to upright posts. Windows opened and closed with wooden hatches or had panes of glass if settlers could afford them. The floors were invariably of trodden dirt.17 None of these houses have survived the ravages of white ants and floodwater to allow us to see them today. Living space must have been difficult for the families along the river. Not only did their small house accommodate adults and young children but it also served as the lodging place for any employed labourer, house servant or government men (assigned convicts). The first detachment of soldiers sent to the Hawkesbury, around 80 men, were also billeted with the settlers. Floor space at night was fully used.

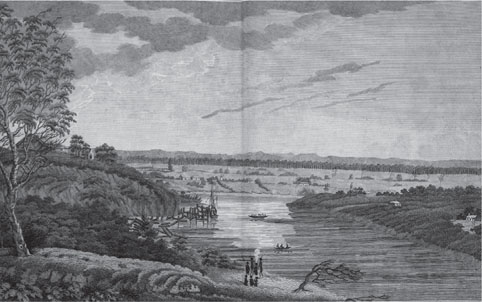

The Argyle Reach riverside farms were busy places. Clearing had begun when the grants were taken up. With the exception of Ross Farm and Archer’s Farm, all grants along the Argyle Reach had been under cultivation every season. Virtually all trees had been felled and the riverbanks cleared of undergrowth. Some settlers along the river had rolled fallen trees into the water, causing dangerous log jams that became hazardous to boats. The master of the colonial schooner, the Francis, plying goods and stores to and from Sydney, complained of the danger this posed to his vessel.18 But those problems were largely over by 1799 and craft of all sizes were now able to reliably navigate from the mouth of the river to a wharf at Windsor Reach. Several settlers had rowing boats to cross the river and move grain or small livestock to the government storehouse on Windsor Reach. A government crew of sawyers cut useful timber, and probably another work gang built the farmhouses for newly arrived settlers. Paling fences usually divided each 30 acre farm from the next, presumably not for the sake of privacy but for restricting farm animals, usually pigs and goats, from wandering outside the farm’s boundaries. Timber hutches and fenced pens served as animal enclosures. Keeping animals tied up was not always an option. Rope and cordage of any kind was virtually unavailable in the colony but by 1797 Hawkesbury settlers started using the bark of the local kurrajong tree to make rope. No doubt a technique learned from local Aborigines, the bark, once soaked in water, can be beaten like hemp, then spun and twined into a strong cord the settlers called ‘kurrajong’.19

In the five years since the beginning of farming at the river some farmers had well-developed piggeries and sold fresh pork to the government store while others had bred a few goats into a small herd. Wheat and maize were the grains taken into the government store. Regular checks were made of acreages sown and expected harvests—information that was reported to the governor. Breeding cattle was still the exclusive privilege of larger farms like John Macarthur’s Elizabeth Farm at Parramatta. Most Hawkesbury farms had a few chickens and pigs fed on leafy greens from the ubiquitous vegetable gardens. Goats came to the Hawkesbury probably initially for milking and for fresh meat although photographs taken decades later show goats being used to pull small carts. Dogs quickly became useful farm animals to have. They could help the farmer with livestock, chase down game, and, most importantly, alert the householder when strangers approached.

When government gave a land grant they also gave the new settler a start in terms of seed, equipment and stock. Each new owner received one or two animals, perhaps poultry, and seed for vegetable gardens and for the first crop, usually maize (corn). Wheat and maize seed for planting the next crop generally had to be kept from one year to the next. The alternative was to borrow or buy the grain from a neighbour or from the government grain store. It was also common practice to keep some wheat and corn for home use. A few people had a steel mill for grinding grain. It was very likely the type clamped to a table and the handle turned by hand. The government storehouse may have had such a mill as we know that Thomas Plomer was on his way to grind some corn when he saw a pig in the farm’s creek. When he tried to extricate the animal he was attacked by the pig’s owner, his neighbour Mark Flood. The incident ended in a heavy court fine for Flood and Plomer receiving the attention of the local surgeon for a head wound that had been inflicted with a pitchfork.20

‘A view of part of the town of Windsor, in New South Wales’, drawn by Philip Slager in 1813–14 and published by A. West in Sydney in 1820–21. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

Vegetable gardens were most likely located between the house and the river so that the water supply was nearby. Scooping water up with a bucket or hand operating a suction pump, as in ships, were the likely methods of bringing water up to a garden. Potatoes, parsnips and cabbage were popular vegetables and some people grew melons. Farming implements were another government supply, mostly hoes, spades or shovels, sickles and axes. Horse-drawn ploughs came later when a settler could afford the imported or locally made implement together with the ox or horse to pull it.

Most women convicts in the colony were assigned as servants to settlers or the civil and military officers. De facto partnerships arose from many of those assignments. The Archer, Freebody and Forrester couples were examples. Among the officer ranks the assignment system also offered more possibilities than just the master–servant relationship. One officer euphemistically referred to the practice as taking ‘a Lady into keeping’, albeit their expectations were more than for a tidy house with meals on the table.21 De facto partnerships and children were often the natural result. For the officers this was viewed as acceptable behaviour given their circumstances—far from the disapproval of friends and family back home, including their own wives. But these relationships were rarely written about and certainly go completely unacknowledged by diarists such as David Collins, the colony’s first Judge-Advocate. Collins was being careful as he wrote his diary for future publication. He had a wife back in England and a de facto relationship with a convict woman in Sydney, a woman who bore him two children. This lack of openness makes it difficult to explore the lives of women convicts assigned to officers in the early settlement. They are largely hidden from our view by the reticence of the officers to reveal their living arrangements. Sometimes when those same officers left the colony they made arrangements for their partners and children that reveal to us something of the obligations and affections they developed. The clergymen of the colony had a different view. Those women living in a de facto relationship they might have called a concubine. But where a woman might change her mind about which house she wanted to keep, they were more likely to condemn her as a whore.22

For the Argyle Reach settlers in 1799 there was as yet no school at the Hawkesbury. With the numbers of young children increasing there must have been talk along the river about the looming need for one. Between the five family units described above, there were fifteen children. The baby boom along the Argyle Reach was typical of what was happening all around the Hawkesbury settlement. The count of children at the river in June that year was 148 plus five orphans while the total number of women of all ages was only 114.23 Finding a wife and starting a family was what many new grantees might have hoped for when they started farming—a partner to share their bed and their burden. The odds, however, were against them when the numbers of women were comparatively so low.

The nearest church was in Sydney and some made the journey for a baptism. Closer to home were several houses licensed to sell spirits, one being as close as the Coach and Horses Inn licensed to Thomas Rickerby on his grant at the bend into Argyle Reach. The Cross Keys Inn lay in the south-east corner of the government precinct, and another, The Bush Inn not far beyond. The Hawkesbury had a reputation with those who chronicled life in the colony as a place where settlers squandered their hard-earned produce in barter for liquor, where drinking and laziness went hand in hand and little could be expected from the low life who lived there.

Another view of the kind of trouble that arose from time to time at the Hawkesbury comes from the magistrates’ hearings in Parramatta. Common complaints heard by Magistrate Richard Atkins or the Reverend Samuel Marsden were: breaking and entering, stealing food or clothing or other possessions from houses or barns, receiving stolen goods, passing a forged bill or promissory note, and absconding from work. Sometimes it was a soldier slipping away from duty, more often it was a convict taking his leave of a work party or running away from his assignment. Men absconding into the bush, sometimes to live within an Aboriginal community, became a problem. They would steal food and clothing from settlers’ huts or commit robbery on the roads. If brought to court the least charge was that of being a rogue and a vagabond, serious enough to attract an extra sentence in a chain gang or banishment to the Coal River (Newcastle) coalfields. Common assault, wife beating and occasional murder went to trial in the criminal court in Sydney if the evidence looked strong enough for a conviction. The assault on Thomas Plomer by Mark Flood is an example of how white on white violence was dealt with. Violence of other hues—white on black—was a serious issue for the governor’s control of the penal colony. Until the murder of the two Aboriginal boys, the criminal court failed to convict anyone for harming an indigenous Australian. Black upon black violence was Aboriginal business, a spectator sport for white people and not a matter for the colonial courts.

Drinking and gambling took its toll at the Hawkesbury although there is no reason to think these activities were more frequently indulged in than in the other farming districts.24 Accumulating debts, however, was for farming settlers almost impossible to avoid. The colony’s officers (civil and military) had a monopoly in purchasing goods from visiting ships and that meant that all imported goods were expensive. Wine and spirits, tea, sugar, tobacco, crockery, cooking utensils, soap, clothing and any drapery items were, when available, sold at premium prices. It meant that farming families found it difficult to stay out of debt. Wine and spirits flowed freely into the colony after the founding governor, Captain Arthur Phillip, sailed away. Liquor soon became the usual way of paying labour and another necessity the farmer had to purchase. The trading chain of wholesaler to retailer, and sometimes yet a second retailer, meant that goods could pass through several hands, each time gaining a mark-up. By the time settlers purchased the goods at the Hawkesbury the price was exorbitant. Some people sold their crops in advance of the harvest, an undertaking with obvious inherent risks. Perhaps the Argyle Reach settler David White had taken that gamble. In June 1798 he appeared in the Judge-Advocate’s office to answer a complaint that he had not fulfilled a contract regarding the sale of his crop.25 Luckily the complainant was lacking evidence to support his claim and the matter was dismissed. Robert Forrester had also been in trouble over debts two years previously. He had borrowed money but had to collect some owed to him before he could settle.26

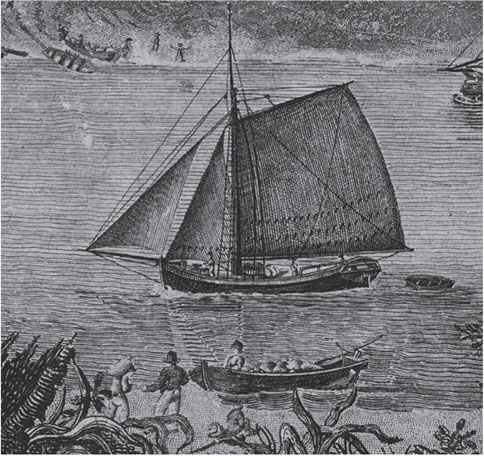

People loading bags of produce into a boat and, on the other side of the river, unloading the produce and carrying it up the bank to the government storehouse. Part of a view across Windsor Reach drawn 1813–14 by Philip Slager and published in 1820–21. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

A few farmers took even greater risks with debt. Notwithstanding the fact that Hunter banned the trading of grain for spirits, some did sell their grain to traders in exchange for liquor to pay their farm workers. A further obstacle to farmers was the way in which the government storekeeper at the Hawkesbury operated. Settlers complained that he gave preferential treatment to selected settlers when he had limited space to receive into the store.27 Those left without a ready market for their grain were compelled to sell at reduced prices to traders and speculators. In 1798 the settlers told the Governor that the same person purchasing at the forced discount would turn around and sell the grain to the government store at the proper price.28

The cost of farm labour certainly contributed to debt. The Hawkesbury farmers laid out their costs to the Governor and pleaded with him not to reduce the price of grain into the store. They claimed that to produce one acre of wheat yielding, on average, 25 bushels, the cost was around £13 5s 9d. And if you included the initial cost of clearing the ground an additional cost was £6 10s per acre.29 When the government was paying only eight shillings a bushel for wheat into the store the money received on one acre would have been just £10, not enough to cover costs.30 Hunter finally relented and in December that year allowed wheat grain in at ten shillings a bushel saying he would definitely reduce the price the next season.31

Regardless of accumulated debts most settlers continued farming. No doubt many put their own labour into the enterprise rather than paying others at every turn. Certain jobs require more hands for short periods. When only hand tools are available many hands are needed to reap the wheat, pick the corn, carry the harvest to the barn, stack and thresh, or remove the husks. With only 98 male convicts in the settlement most farmers did not have this source of free labour. People like David White, Simon Freebody and Robert Forrester may have lost their assigned convicts some time in 1796. Edward Powell, by virtue of his job as constable, was one farmer on Argyle Reach with the cheap labour of an assigned convict. Most farmers had to employ help, at least for those peak times. Wives were probably a help but in a limited fashion if they had babes in arms or a toddler pulling at their skirt. Very likely neighbours helped each other in a cooperative way. You helped your neighbour reap his wheat or pick his corn if he did the same for you. The women probably had similar arrangements. Perhaps one would make butter or cheese for several families while another would bake bread in return. Child minding might also have been done in a cooperative way.

View of the Hawkesbury showing the main wharf in an un-finished or demolished condition. Drawn by Captain Wallis of the 46th Regiment and published in 1820. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

Some aspects of life along the river require our imagination to fill in the gaps where the records are silent. It is one thing to deduce the nature of day-to-day activities and to weigh up the difficulty of challenges we know they faced. It is another to know their hopes and aspirations, their regrets and sorrows. How often did thoughts of their families back home in Britain occupy their thinking? Letters might give some insight. We have three such rare gems that relate to one of the Argyle Reach settlers. Received by Thomas and Jane Rose, they were written by members of Jane’s family in Dorset. Thomas Rose was Betty Powell’s uncle. Betty had married Edward Powell and the couple were on the Argyle Reach in 1798. Two of the three letters reveal something of what Betty had written home to her own mother.32

A boat carries cattle and owners across the Hawkesbury River. Detail from a drawing by Captain Wallis, etching published in 1820. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

The first letter, dated 10 March 1798, begins: ‘I received a letter from you, and your sister Elizabeth received a letter also from her daughter [Betty Powell nee Fish]’. The writer relates how they are fearful of a French invasion at any moment and how the taxes were so great they were ‘hardly to be borne’. Thomas and Jane Rose must have asked for some things to be sent out but Jane’s parents say they do not trust the goods would be delivered so they do not send anything. Then Betty is mentioned more directly. ‘Betty Fish gives the place an exceedingly good character and make no doubt but they shall make their fortunes and I hope you will the same.’

So Betty had expressed her optimism in a letter to her mother, written most likely sometime in late 1795 or early 1796, as her family received it around August 1796. Betty and her husband Edward Powell would then have been farming at Liberty Plains.

The second letter is undated but probably written in late 1797 or early 1798. At that time England was expecting a French invasion and there was a drive to arm as many people in the country as possible.33 ‘We have now horses and men called yeomen cavalry and another sort called provincial cavalry for the defence of the nation.’ The letter gave more news of heavy taxes for the war effort and again referred to another of Betty Fish’s letters home:

Betty Fish’s letter was very particular to her mother and could wish of her mother being able to come over and settle as they have a great prospect of doing well there, and far beyond what they should ever been able to do in England. I am sorry that I cannot receive one comfortable letter from you, but all grumbling and full of complaints. I hear you have a good track of land and you must expect it will take time to clear it, but consider what a fine thing land of your own is and pray be content and pray for your health and God’s blessing yourselves as I and your mother do for you.

While people back home were feeling oppressed under the weight of the war effort, Betty’s letters must have given comfort about their prospects on the other side of the world. Whether Betty was as sanguine about their opportunities once they were at the Hawkesbury, we can only guess.

As the year 1799 opened, a dry summer parched the farms along the Argyle Reach. Another year of drought limited their harvests and the high price of goods and labour meant most were in debt. A more serious challenge came upon them in March suddenly and unexpectedly. Heavy rain in the mountains flowed into the river in such volume that the water rapidly overflowed the banks. It had done so on several earlier occasions, but not to flood the whole plain as it did this time. The peak height was recorded as 50 feet above the usual river level. A map of the 1806 floodwaters, a flood that had its peak at 47 feet, shows the riverbanks of Argyle Reach sitting above the flood level although water covered the backs of the farms, away from the river. In this March 1799 flood the extra three feet probably made for inundation of the whole of the Argyle Reach farming land. Governor Hunter told the British Home Secretary, the Duke of Portland, the raging water was ‘so powerful it carried all before it’. A few men in rowing boats heroically rescued people from the ridges of their houses. Water covered most dwellings and the whole country, Hunter wrote, looked ‘like an immense ocean’.34

The upper Hawkesbury River areas settled by 1800

Hunter was sceptical when he told Portland, ‘Some say the natives foresaw it and advis’d the inhabitants’. Despite the disaster being a surprise, only one man lost his life. The Argyle Reach families were able to evacuate their farms to the higher ground before floodwater cut them off. Those across the other side of the river had to negotiate the river itself to escape to safety. The flood carried away poultry, pigs and other livestock. A large measure of the last harvest was swept away, as was much of the contents of their houses.35 It would have been a sorry sight—a couple of hundred people, men, women and children, standing on the high ground of Windsor Reach, looking out across that ocean of water, at their feet the few possessions they had quickly gathered up before abandoning their homes. Behind them stood the government precinct with the commanding officer’s house, the barracks, the two inns and a few small houses. Below them the water swirled, including where the government grain store had stood.

After a few days the floodwater receded and left a replenishing layer of silt across the ground. As the soil dried the settlers and their men got to work planting wheat seed issued under Hunter’s orders. He was hopeful of bountiful harvests for the next couple of seasons. But no sooner had the grain germinated than a plague of caterpillars arrived and ate the new shoots. Pressure was on the Governor as he was deluged with applications for clothing and bedding. He had none to supply but told Portland, two months after the event, he would do all he could to relieve the settlers’ distress.

By mid-1799, the Hawkesbury farming area had grown to have a white population of almost one thousand. That represented one-fifth of the population of the New South Wales penal colony on the mainland. They were spread along the river for over 30 kilometres. The farms occupied a significant and important part of the traditional home of Aboriginal people. They were used to camping, fishing, hunting and gathering food along those same riverbanks. The settlers and their farming practices interrupted that traditional activity.

The usually peaceful relations with the traditional landowners could suddenly and unpredictably change. Evidence from the trial of the five Hawkesbury settlers for killing the two Hawkesbury Aborigines reveals how some settlers encouraged good relations with local tribesmen who plainly knew their own country well. It was to the settler’s advantage to maintain peaceful and cooperative relations and be tolerant when Aboriginal people crossed the farm or called at the farmhouse door for something to eat. But fear of attack must have pushed some people to be on their guard with a musket at the ready. During those first five years of farming settlement (1794–99) the settlers killed Aboriginal people with a frequency that made it almost commonplace. According to a man named Francis Molloy, during his four and a half years as acting surgeon at the Hawkesbury, by October 1799 there had been 26 white people killed and another thirteen wounded.36 No count was ever recorded of the number of Aborigines killed, but Governor John Hunter thought it would have been many more.37 However, the colony’s relations with the Aborigines of the upper Hawkesbury area had begun peaceably. Governor Hunter knew that himself. He was part of Governor Phillip’s exploratory party when they had their first encounter.

Drought, flood, insect plague and the high cost of goods and labour did not deter the settlers of Argyle Reach from continuing to try and make good. But a challenge of a different kind awaited some of them after the flood had gone, after the caterpillars had disappeared and the next wheat crop was in and growing. The murder of their neighbour Thomas Hodgkinson and his companion James Wimbo would lead to their act of retribution, the consequences of which placed Edward Powell, James Metcalfe, Simon Freebody, William Butler and William Timms before a criminal court in Sydney.

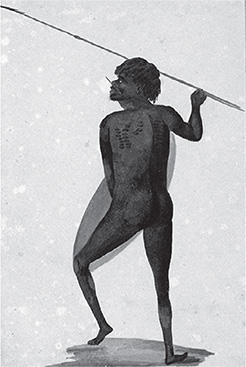

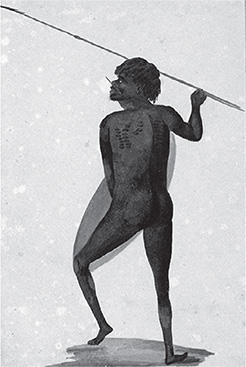

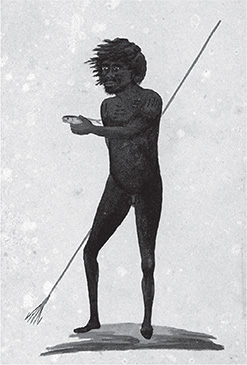

Aboriginal man with shield, spear thrower and spear, in action

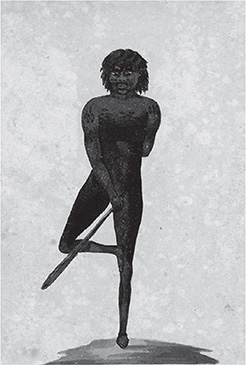

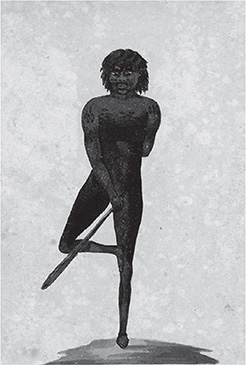

Aboriginal man with club

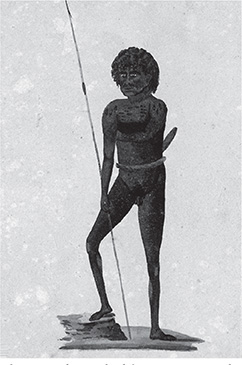

Aboriginal man holding a spear with a throwing stick in his belt

Aboriginal man holding a five-pronged fishing spear and offering a fish

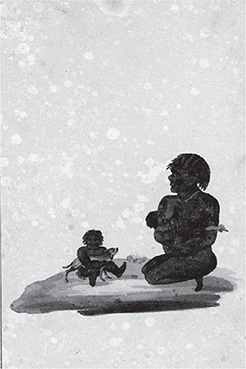

Aboriginal woman in canoe fishing with a line

Aboriginal woman suckling a baby with another child holding a dog

Drawings of Australian Aborigines, pre-1806, attributed to George Charles Jenner and W.W. [William Waterhouse]. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

a Thomas Hodgkinson’s sentence had been completed either by 1794 or 1798, the records being unclear as to whether he was the Thomas Hodfkiss/Hodgkins who arrived on the William and Ann in 1791 or the Thomas Hodgkins who arrived on the Britannia the same year.

b Lewin’s watercolour picture (p. 24) shows a house on Ross Farm although the date of that painting is at least six years after 1799.