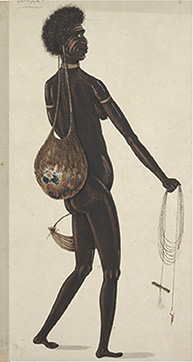

As an initiation into manhood, Aboriginal boys of about ten years of age had one front tooth removed. Drawing published in Collins’ An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Volume 1.

3 Hawkesbury Aborigines Encounter British Colonists

Part 1: Amicable Beginnings

Some of the people living on the Argyle Reach already knew the two young Aborigines who were murdered that September evening in 1799. Jonas Archer knew and named Jemmy although he did not name Little George. John Tarlington, a defence witness who gave his testimony on the last day of the trial, knew the names of both young men. Tarlington told of their involvement in a murderous attack that occurred at his own house eighteen months earlier. It is one of many violent clashes in the story of black–white relations at the Hawkesbury between 1794 and 1799. That sort of incident tends to dominate the historical record and give a somewhat skewed view of relations between the newcomers and the indigenous locals. It’s very possible however, that the friendly interactions first reported—those between members of Governor Phillip’s 1791 exploration party and the Aboriginal people they came across upon entering the upper Hawkesbury area—represent a cordiality that was more the norm.

Jemmy and Little George belonged to that area of the river, the upper Hawkesbury—a river they themselves called ‘Deerabbun’.1 David Collins, the first Judge-Advocate and Governor Phillip’s secretary, referred to the Aboriginal people living in that district as belonging to the ‘wood tribe’. However, ‘Buruberongal’ was the name used by an Aboriginal man who was within his traditional territory of the upper Hawkesbury in April 1791. Phillip’s expedition came across him as they made their way north from Parramatta to the Hawkesbury. He identified himself as Burowan of the Buruberongal.2

Phillip’s purpose on that trip was twofold. It was to find land suitable for farming and to find out if the Hawkesbury and Nepean rivers, which had been discovered separately, were actually one and the same. Two different accounts of the expedition are given in the books written by men who were amongst his party. Lieutenant Watkin Tench gave a shorter version than Captain John Hunter whose penchant for accuracy and detail far exceeded that of Tench. Two Aboriginal men from the Sydney region were with Governor Phillip’s party. Colebe and Ballederry were both Cadigal men from the coast. Soon after the party left Rose Hill (Parramatta), Colebe told them they were passing through land belonged to the ‘Bidjigals’. He thought them mostly dead of the disease (smallpox or possibly chickenpox) that had recently swept through the Aboriginal population.3 After three to four hours walking they heard an Aboriginal man calling out, apparently hunting for his dog. The small boy with him carried fire on a piece of tea-tree bark. When Colebe and Ballederry made contact with Burowan both parties were wary of each other. The introductions and an explanation of the white men’s purpose in being there took some time. Despite having some difficulty with language they were able to make themselves understood. The Buruberongal were apparently traditional enemies of the Cadigal and as far as Colebe was concerned they were bad people.

John Hunter described Burowan as being a young man carrying a stone hatchet, a throwing stick and spear, his hair ornamented with the tails of several small animals. His front teeth were intact unlike the Sydney tribesmen who had one front tooth knocked out. Burowan would not accept the invitation to join the white men at the fire. However, before parting company he obligingly pointed the way to the river. The next day the expedition moved north-west and arrived at the riverbank. There the stream was particularly wide, about 300 feet across. The party were some eighteen and a half miles from Parramatta.

The territory over which the clans of the upper Hawkesbury ranged, according to historian Jan Barkley-Jack, is thought to have included the Blue Mountains area of Springwood, Shaws Creek, Kurrajong and Yarramundi (named after the Aboriginal leader), Richmond, Windsor, down the river as far as Sackville, and over to Toongabbie.4 From the descriptions given in the 1799 trial, it appears the Aboriginal people moved about their territory in groups composed of those who were blood-related. Today, we write about these groups as being ‘clans’, each clan being made up of family and related kin. The number in a clan could be a few, or as many as 30, or even more. They sometimes coalesced with a neighbouring clan to form a large body of 100 people or more. At any one time it seems that several groups were present in different places within the tribe’s own territory. The women do not appear to have always been part of the groups communicating with the white settlers. Perhaps they hung back because of a perceived risk to their safety. Nevertheless, there were several recorded incidents when a large group raided a farm and the women and children were involved.

As an initiation into manhood, Aboriginal boys of about ten years of age had one front tooth removed. Drawing published in Collins’ An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Volume 1.

The language the upper Hawkesbury Aborigines spoke is known today as the Darug (Dharug, Daruk, or Dharruk) language and the people who spoke this language are also known by the collective name of Darug. The coastal people who lived between Port Jackson and Botany Bay spoke the same language but in a different dialect, referred to today as the Eora dialect.5 Further down the Hawkesbury was the country of the Darkinjung people who spoke a different language. Their traditional country included the Colo and Macdonald Rivers that fed into the Hawkesbury.6 The Aborigines to the north, in the Port Stephens area, spoke yet another language.

Phillip’s party met more Aboriginal people, probably Buruberongal, once they followed the river itself. Several canoes were seen and Colebe and Ballederry, wanting to speak to the owners, bade the rest of the expedition party hide in long grass. They waited for the canoes to draw abreast but they instead pulled up short on the bank opposite. So Colebe had to call out to attract attention. An old man, apparently recognized by Colebe, answered and came over in his canoe. After some questioning Colebe and Ballederry concluded that these people were journeying to collect stones for making hatchets. John Hunter identified the old man as Go-me-bee-re, and Watkin Tench wrote his name as Gombee’ree. Colebe and Ballederry talked to him about each individual in Phillip’s party, and Gomebeere went to his canoe and fetched two spears, two stone hatchets and a throwing stick to present to Phillip. Hunter described the skilfully made barbs on the spears. They were somewhat different to those from the coastal tribes. Phillip reciprocated the gift with two small hatchets, fishhooks and some bread. Gomebeere looked at the bread without knowing what it was until Colebe showed him what to do. He then ate it without hesitation.7

Watkin Tench described Gomebeere as ‘a man of middle age, with an open cheerful countenance, marked with the smallpox, and distinguished by a nose of uncommon magnitude and dignity. He seemed to be neither astonished or terrified at our appearance and number.’

As the expedition moved along the banks of the river, Gomebeere followed in his canoe. Another canoe with a woman and child also followed. At one point Gomebeere came ashore to take the lead and show them to an easier path used by his own people. When the whole party stopped for the night two more Aborigines appeared and joined the party. Yal-lah-mien-di (Yellomundee or Yarramundi), and a boy named Jim-bah (or Deimba) had also been canoeing on the river. They soon showed that they, and Gomebeere, were intending to stay the whole evening while their womenfolk remained on the opposite shore. In the convivial time spent together they explained that their food was primarily small game and some roots of a wild yam. They were ‘tree-climbers’, according to Colebe, living by the small animals they caught. It was woman’s work to fish from the canoes, mullet being the main catch. The next day Gomebeere gave an astonishingly skilful demonstration of tree climbing. By cutting small notches little more than an inch deep, one after the other as he went up, he could climb to a great height. The ball of the great toe was inserted in the notch and held his weight as he lifted, hatchet in mouth, to cut the next notch. Gomebeere enjoyed the demonstration and, as Tench described, all the while ‘talking to those below and laughing immoderately’.8

View of Port Jackson published in 1793 by Alexander Hogg. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

During an evening socializing together around a fire the visitors happily spoke the words for different parts of the body as Tench and Hunter made notes. Gomebeere showed them the scar on his side from a deep wound and expounded to Colebe about the wars he had fought in receiving such wounds. This probably led Colebe to think of his own wounds as he asked Yallahmiendi to perform a healing on him. The latter having agreed, Colebe asked for some water and Tench handed him some in a cup. Colebe ceremoniously gave it to Yallahmiendi who took some water into his mouth, threw his head against Colebe’s chest and spat out the water. He then began to suck strongly at the skin just below Colebe’s nipple. The operation was repeated twice, and when finished, Yallahmiendi moved away a few paces, appeared to extract something from his mouth and throw it into the river. The officers were fascinated by the ceremony and examined Colebe’s chest but the skin was unbroken. Yallahmiendi had been seen slyly picking up something from the ground before throwing the object in the river. But nevertheless they were impressed. Colebe was pleased. He said that Yallahmiendi was a ‘Carradygan’ or doctor. He believed two splinters of a spear, with which he had been formerly wounded, had been drawn out. Yallahmiendi’s tribal people were all talented doctors, according to Colebe.9

The officers had enjoyed their time with these Buruberongal clansmen. Tench wrote:

The doctors remained with us all night, sleeping before the fire in the fullness of good faith and security. The little boy slept in his father’s arms, and we observed that whenever the man was inclined to shift his position, he first put over the child, with great care, and then turned round to him.10

One remarkable aspect of that first encounter between Phillip’s large group (around 21 people in total) and the Buruberongal, was the friendly openness with which they were received. Their frankness and confidence surprised the officers. When it came time for a parting it was all in friendship and good humour. Colebe and Ballederry gave them a formal slight nod of the head, but the officers shook them by the hand, which, according to Tench, ‘they returned lustily’. Perhaps it was from this encounter that some Aboriginal men of the Buruberongal began adopting names of the white men they met. John White, the Colonial Surgeon, was in Phillip’s party and we know that Major White was one of several adopted names. The likely Aboriginal pronunciation of Mister White was ‘Midjer White’, which became corrupted to ‘Major White’ when repeated by the colonists.11

Governor Phillip’s policy was to offer the hand of friendship, not only in the literal sense. His own behaviour was an example to the officers around him. John Hunter, in particular, gained much of his own approach to Aboriginal people from observing Governor Phillip. In the early days in Sydney the Aborigines stayed away from the settlement after several of their number were wounded or killed. Determined to carry out his Admiralty orders to forge a good relationship with the natives, Phillip decided to force the issue. With a rationale that is almost beyond current day understanding Governor Phillip decided to take the initiative: if they would not come into the settlement voluntarily he would capture one or two and impose his hospitality upon them. According to Phillip, a demonstration of superior force did not necessarily begin the relationship on the wrong foot. It was like domesticating a wild animal—you captured it by force, tied it up until it stopped struggling for freedom, while at the same time offering food and drink and other comforts. And that is what the party sent out by Phillip actually did. They grabbed two Aboriginal men by force at Manly Cove on the second last day of 1788. One escaped but they carried the other back to Sydney in their rowboat. Arabanoo was his name and he was judged to be about 30 years of age. He was delivered to Government House, Phillip’s residence, where his leg was shackled and a convict stationed to prevent his escape. He apparently soon became reconciled to his situation and accepted the friendly treatment of those around him. For a few months Arabanoo had the freedom of the settlement and came to learn the names of those officers who frequently called at Phillip’s house. Once, on meeting Captain John Hunter, he indicated he wanted to go on board Hunter’s ‘nowee’, the ship anchored in the cove. So Hunter invited the Governor to lunch on board, and Arabanoo accompanied him. Hunter was please that Arabanoo proved to be a talkative and good-natured guest. Sadly just a few months later Arabanoo died from contracting a disease that manifested itself in sores over the body. It was an epidemic the colonists thought was smallpox and it decimated Arabanoo’s countrymen all around the harbour while not affecting the Europeans.12

Phillip used the kidnap strategy again, later that same year, when Bannelong (Bennelong) and Colebe (Colby) were captured and brought to Sydney. He wanted a couple of native men to learn enough English that they could be of use in communicating his wishes to their people, in this case the Cadigal.13 Using trickery in an aggressive act of capture, followed by the soft glove of kindly friendship, served Phillip’s purpose. It demonstrated superiority while showing an intention for friendly coexistence. That these actions might also have demonstrated a capacity for treachery seemed to Phillip to be of no great importance—the unfortunate price for a desired outcome perhaps.

When an Aboriginal man severely wounded the Governor’s gamekeeper in an apparently unprovoked attack, Phillip thought a lesson of punishment had to delivered. Several witnesses had assured Phillip that his gamekeeper was unarmed and had in fact laid down his arms in a gesture of friendliness. As on many other occasions there was no attempt by other Aboriginal men to protect the perpetrator from being identified. Quite the opposite; the attacker was named as Pemullaway (or Pemulwy) by several Aborigines in the settlement. Perhaps it was because he was from a different clan, the Bejigal, of the Botany Bay district, a rival group to that of the informers. For Phillip the time had arrived to use a superior force to teach them a severe lesson. The punitive party, with supplies for several days, marched out of the settlement; two captains, two lieutenants, four non-commissioned officers, 40 privates, the surgeon and surgeon’s mate from the ship Sirius, and three persons who were with the gamekeeper when he was wounded.

Every onlooker would have understood the Governor’s intention. They were to return to the place of attack, search that part of the country for natives, capture six, or if that proved too difficult, kill six. No women or children were to be harmed. Spears and all other weapons they came across were to be destroyed and left on the ground. When they saw any natives no one in the party was to hold up their hands as this the natives understood was a gesture of friendliness. The party returned three days later having had not one fragment of success. Although they fired at a group of people at the head of Botany Bay they injured no one, and those they aimed their guns at swiftly disappeared from sight. Phillip was determined to make the point. He sent out another party with the same orders. But it too failed. Frustrated and annoyed, Phillip must have justified to those around him that the attempt was worthwhile in that it gave the general understanding to the Aborigines that the Governor was angry enough to want to punish them.14

The law was another subject that Phillip thought needed clarifying. Phillip wanted to impress upon the Aboriginal people the superior authority of the settlement’s law over Aboriginal customary law. If they would rely on the Governor handing out punishment instead of seeking their own retribution it would be a big step towards peaceful relations. To this end, when Phillip knew of a convict or soldier robbing or mistreating an Aboriginal person, he would order a flogging and invite the victim to watch the penalty being inflicted. However, an incident in June 1791, related by John Hunter, clearly shows how Aboriginal law was the only law the Aborigines would follow.15 At the newly established settlement at Parramatta several Aboriginal men were bartering the fish they had caught for bread, rice and vegetables. Phillip was pleased and hopeful that this kind of exchange might cement good and useful relations. One of the young men carrying on this trade was Ballederry. Regardless that strict orders were in place that the natives’ canoes should not be touched, Ballederry’s canoe was smashed. He arrived at the Governor’s hut in Parramatta in ‘a violent rage’. Armed for battle with his throwing stick and several spears, he had painted his hair, face, arms and breast red. Phillip tried, at length, to persuade Ballederry not to take his revenge and kill a white man. He promised Ballederry that he would himself have the offenders punished. The young man finally agreed and the guilty convicts were brought forward, questioned and punished before Ballederry’s eyes. During the interrogation, however, Ballederry’s behaviour clearly showed that it was his wish to punish the men himself. Phillip gave him some small gifts in compensation for his loss. Determined to soothe the young man’s rage for revenge he even lied that one of the guilty men had been hanged. Ballederry seemed satisfied. However, three weeks later some Aboriginal people turned on a convict who strayed some distance from the settlement. Spears were thrown and the convict was wounded in the back and side before getting away. Local Aborigines gave Phillip the names of those in the attacking party, and Ballederry was one. It was clear that this was payback for the loss of his canoe. There was no doubt. John Hunter wrote that it confirmed the general opinion—‘that these people do not readily forgive an injury until they have punished the aggressor’. British justice was not going to deputize for Aboriginal law. And what was also clear was that Aboriginal revenge justice might target any one of the offender’s group—not necessarily the actual offender.

Hunter was not the only person to characterize Aboriginal payback as being targeted to any person with a relationship to the offender. Richard Atkins also noted in his diary in June 1792 some details of the death of an Aboriginal woman. An Aboriginal man had murdered a tribesman named Yalloway and had burnt his body. Atkins wrote:

It appears to be a general determination that the friends of the murdered person revenge his death by the murder of the Guilty person or upon any relation they may have an opportunity of doing it on. The wife of Yalloway a few days after her Husbands death met a young girl, a relation of the Murderer, and immediately took a large stone and beat her over the head till her skull was fractured in many places and she died a few hours after. Upon this being mentioned to some of the Natives they were not in the least surprised at it, but said it was a natural consequence.16

Those first few years were a bumpy ride to maintain friendly relations. Governor Phillip continued to hold out the hand of friendship and entertained many Aboriginal people at his residences in Sydney and in Parramatta. Some, like Bannelong, developed a special friendship with the Governor, one that put them in high regard with their fellow clan members. Aboriginal visitors were always treated with cordiality and given food while at his house, or for their journey when they departed. They regularly slept within his house yard, usually in a small shed. For a short period a young Aboriginal woman became, at her own request, one of the maid servants in Phillip’s household. She left of her own choice one day, shedding all her clothing as she departed while keeping a cap to keep her shaven head warm.

Out from the main settlement the spearing of unarmed colonists persisted as a problem that Phillip was unable to control. After he left the colony more farming areas opened up and relationships with the Aborigines in those new locations were sometimes volatile. At Toongabby (now called Toongabbie), the Field of Mars, Kissing Point, Lane Cove and Liberty Plains, Aborigines were paying frequent visits to settlers, asking for food and other handouts, going inside the houses, sitting and talking, sharing local information. But settlers were not always welcoming and willing to share their hard-earned produce or government rations. And their refusal was not necessarily accepted gracefully. Perhaps for the Aborigines, the settlers’ food represented the bounty of their own Aboriginal home country, bounty that was rightfully theirs, or at least should be shared amongst everyone. It was the settlers who were encroaching on Aboriginal land and failing to recognize Aboriginal rights and practices regarding food. Some settlers, once they had a firearm, were intolerant of any Aboriginal visitor, even firing upon them when they crossed their farm. When a settler impeded access to a river or to a lagoon this would have been a serious problem for people used to trapping fish and other animals in those locations.

By the time European farming started at the Hawkesbury, Aboriginal men were regarded, especially at the outskirts of settlement, as dangerous and unpredictable, capable of spearing anyone travelling alone and unarmed. In contrast, some Aboriginal people lived amongst the town folk in Sydney and Parramatta on friendly terms, donning the colonist’s clothing and appearing, at least superficially, to take on white man’s ways. Phillip had hoped the Aborigines would somehow integrate into the colony, prefer the shelter and comforts the settlement offered, and be grateful for the food, clothing and utensils given. He hoped the settlers would continue his policy of amicable relations. It was rather idealistic. Misunderstandings inevitably occurred. Some people stole valuable Aboriginal possessions such as fishing gear or spears for their own collection, objects always tradable with visiting ships. Others offered food but sometimes the Aboriginal recipients wanted more, even all the settler had on hand. And they were prepared to take it if it was not freely given. A few settlers, very few, gave Aboriginal men employment in the field in return for food and alcohol or useful items such as a blanket. Amongst some of the officers there was talk of making slaves of their black visitors. Lieutenant William Cummings was one officer who apparently tried to put the theory into practice with a Hawkesbury Aboriginal man named Charley. The slavery idea must have been discussed at length amongst the officers as Governor King mentioned it again in 1807. He was preparing a memorandum for Governor Bligh on the subject of the natives.17 Enslaving the natives was a much-discussed proposition that King rejected.

Part 2: Trouble From the Start of Settlement

At the Hawkesbury, not long after the first crops were under way in early 1794, trouble started. David Collins wrote in April of the crops at the Hawkesbury looking very promising. One man had planted and dug a crop of potatoes in three months. ‘The natives, however, had given them such interruption, as induced a necessity for firing upon them, by which, it was said, one man was killed.’18 Collins does not tell us who was involved but we can presume the ‘one man’ killed was an Aboriginal man. His diary entry marks the start of violence between the settlers and local Aboriginal people at the river.

Aggression between the two groups escalated over the next few months until finally, in January the next year, the acting governor, Captain William Paterson, sent in the troops. An analysis of the events leading to his decision reveals a chain of violence, white upon black followed by black upon white and so on, each attack being retribution for the one before. Payback was, and still is, a concept understood in all cultures.

At Toongabby, about fifteen miles from the farms at the Hawkesbury, a large number of Aborigines were helping themselves to cobs of corn directly out of a government field. Watchmen, stationed for the protection of the field, told how they saw the natives picking the cobs and filling sacks to carry away. They fired their muskets towards them and then chased them. After some miles the watchmen found and killed three, or so they claimed. They told an embellished story in Sydney, as though it was a heroic battle of pursuit. Having suffered no injury themselves, their story was received with some incredulity. But the watchmen paraded a grisly trophy, ‘a testimonial not to be doubted’—the head of one of those they had killed.19

A few months later, at the Hawkesbury, settler Robert Forrester killed a young Aboriginal boy on the Argyle Reach farms. News of the incident reached Sydney and the story was disturbing— some of the settlers had seized the boy and tortured him by dragging him repeatedly through a fire, or hot ashes, severely scorching the boy’s back. Though bound hand and foot he was then thrown into the river and fired upon with the purpose of killing him.20 Such behaviour from ex-convicts towards the natives was not to be tolerated. An enquiry was called and Lieutenant John Macarthur took evidence on the matter in Parramatta on 17 October.21 There were only two people giving evidence. One was Robert Forrester, the man who admitted to shooting the boy. The other was Alexander Wilson, a settler on Windsor Reach, who related what Forrester had told him after the event. It was, Wilson said, that Forrester was:

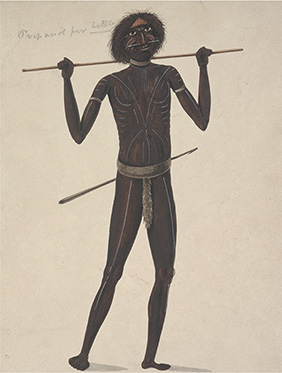

‘No. 1 Wife’

‘Broken Bay Jemmy’ 1817

‘Prepared for battle’

Drawings of Aboriginal Australians circa 1813–19 attributed to R. Browne. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

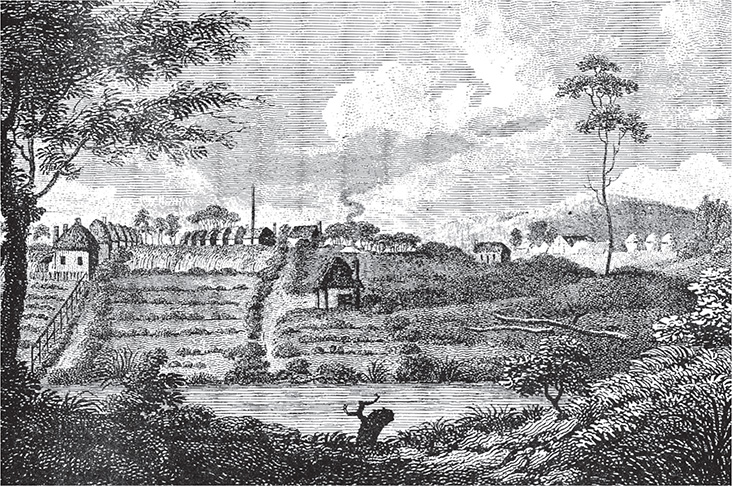

‘A western view of Toongabbe’, published in 1798 in David Collins’ An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Volume 1.

induced to it from intreaties [sic] of humanity the boy having been previously thrown into the river by the neighbouring settlers, with his hands as tied, that it was impossible he could swim to the opposite shore.22

So according to Wilson, Forrester had killed the boy as an act of mercy.

Forrester himself gave a fuller explanation. He said a large party of natives had appeared at the back of his farm. He raised the alarm with his neighbours and together then went out to watch the group. On their way they met a native boy coming towards them. They thought he must have been coming in to find out what firearms the white men had. They took the boy prisoner, tied his hands behind his back and delivered him to Michael Doyle, who was to take the boy to his hut. Not long afterwards Doyle cried out that the boy had escaped and jumped into the river. Forrester and a man named Twyfield immediately ran to the river and saw the boy swimming. Forrester said he was then

prevailed on to shoot the boy by the importunities and entreaties of all around lest the boy should get back to the Natives and induce them to an attack by discovering there was no more than one musket in the whole neighbourhood.

As far as Forrester knew, the boy had not been ill treated in any manner other than what he had said. Alexander Wilson’s evidence, as far as it differed from his own, Forrester said, was false.

It is worth looking at how Wilson’s evidence differed from Forrester’s. There are two points. Firstly, that people, Forrester’s neighbours, had thrown the boy into the river rather than the boy having jumped into it. And secondly, that Forrester shot the boy as an act of mercy rather than to stop him returning to his clan. In the versions of both men there were other people at the side of the river when Forrester fired his musket. But Forrester’s version excludes any torture of the boy, except that of capturing and tying him up. Wilson’s version implicates others in some form of ill-treatment (they threw him in the river) and also in the murder—as accomplices—if they encouraged Forrester to shoot at the boy.

If Forrester and his neighbours had been afraid of attack it would seem that killing the boy was taking a big risk, an act that could inflame the boy’s family rather than soften any hostile intentions. Just as strange is the idea that the Aborigines, if they were contemplating attack, would send a young boy to find out the state of the settlers’ preparedness. Is it likely the boy would have been capable of assessing how many muskets might be placed around the different huts? Did Forrester tell the boy or somehow show him that he held the only musket? Unlikely. It comes back to the credibility of Forrester’s explanation— that letting the boy escape posed a bigger risk than did killing him. David Collins wrote in his diary that many people still considered it ‘a tale invented to cover the true circumstance, that a boy had been cruelly and wantonly murdered by them’.23 Forrester’s story wasn’t believable then, and it hasn’t gained credibility since.

But no other witnesses appeared before Macarthur’s enquiry, nobody willing to give any different story. And so the matter went no further. What might have actually occurred before Forrester fired the fatal shot at that boy in the river? What is more probable? Perhaps the boy was caught stealing vegetables, or a chicken, or corn from a barn. Perhaps there was no ‘large party of Natives’ at the back of his farm. Perhaps, whoever caught the boy, Michael Doyle, Robert Forrester or someone else, decided he needed to be taught a lesson. The tale of torture over a fire, throwing him in the river and shooting him fits more with a lesson of cruel punishment delivered in anger. But that is all supposition now, as it was then when David Collins and other officers in Sydney also discussed those ‘disturbing reports’. Whatever happened, Collins thought the settlers ‘merited the attacks which were from time to time made upon them by the natives.’24 Though others might also have disapproved of what had occurred at the Hawkesbury, official resolve to grub out the guilty parties was not a priority. Macarthur had followed orders and conducted an investigation but it had been a cursory one and nobody was charged.

Soon after the death of the boy, the group of Aboriginal men attacked two men on an Argyle Reach farm, just a few hundred yards from the Doyle and Forrester farms. George Shadrack and his servant John Akers were surprised when Aborigines burst into their hut and badly beat and speared both of them before they could call for help. Akers was so badly hurt he almost died of his wounds.25 But it wasn’t until February the next year that the reason for the attack became clear to the authorities in Sydney. The attack was meant for Forrester, Doyle and a man named Nixon, in revenge for the murder of the young boy. An ex-convict, John Wilson, related this information to the officers in Sydney when he arrived there from the Hawkesbury. Wilson had been living with the local Aborigines. It was his idea of an alternative to finding employment in the colony. He had developed an intermediate language between his own and his Aboriginal companions, and he claimed to understand their grievances. They had given him the name Bun-bo-é but none of them had adopted his name in exchange, as Aborigines were in the way of doing with other Europeans. Wilson said the natives had threatened to kill the three men in revenge. But they had actually attacked Shadrack and Akers by mistake. Mistake or not, they were acting out their own form of justice, and Shadrack and Akers were lucky to escape with their lives. Collins thought that no good would come from Wilson continuing this wandering association with the wood tribe. There was even the possibility that he might side with the natives in attacks on settlers. To prevent Wilson from returning to the Hawkesbury, the government surveyor took him on an exploratory trip up the coast to Port Stephens in the colonial schooner.26

Wilson had made it clear. The September attack on Shadrack and Akers was, in all likelihood, revenge for the murder of the Aboriginal boy. His information adds another name to the list of those implicated in the boy’s death—that of Nixon. The list as we know it is Robert Forrester and Michael Doyle, both settlers on Argyle Reach, Nixon (probably William Nixon, convict worker) and, according to Forrester’s own evidence, Twyfield—that is, Roger Twyfield, a settler whose grant was at the bend into Windsor Reach.27

The violence continued. A few days after the attack on Shadrack and Akers, a group of Aborigines came into the farms grabbing provisions, clothes, and whatever possessions they could lay their hands on. If it was a raid to persuade the settlers they could not stay, it failed on that score. Instead there was a quick response by those settlers the Aborigines had raided. They gathered up the available firearms (presumably by this stage more than the one musket as Forrester had earlier claimed) and followed the raiders. When they found them, the sound of gunfire cracked across the plain, and seven or eight Aboriginal people lay dead.28 If women and children were amongst the killed, it was not recorded. But the determined action put that Aboriginal group in retreat. They fled away from the settlers’ farms, and very likely into the hills, as they were not sighted again for some time.29

Acting Governor Grose, frugal in his reporting, made no mention of the matter in his dispatches. However, the settlers’ actions received David Collins’ approval, albeit given with regret. ‘This mode of treating them [Aborigines at the Hawkesbury] had become absolutely necessary, from the frequency and evil effects of their visits.’ He went on to declare that the settlers had brought on the problems by their own misconduct—having fired wantonly upon the natives, and when the natives scattered, leaving children behind in their haste, the settlers had detained the children in their huts and not returned them despite the ‘earnest entreaties of the parents’.30 It is unclear as to when this behaviour Collins writes of had occurred. Perhaps it happened during the settlers’ pursuit of the group that had raided their huts. More likely it referred to an earlier encounter. When and how it occurred we have no further details. However, Collins’ words evoke a pitiful image—Aboriginal parents returning to a farm hut, keeping their distance but making their quest understood, pleading, wailing for the return of the child they had left behind when they ran in fright from the gunfire.

There was no follow-up investigation this time. The killing of seven or eight Aborigines in retaliation for the raid was seen as a legitimate defence of their farms—regrettable, but condoned. However, it was not a measured response, not an ‘eye-for-an-eye’ retaliation. The Aborigines had not wounded anyone when they pillaged the farms. This was killing Aboriginal people to protect property. Collins gives us insight into how the authorities viewed these matters. Cruel torture of a native would not be tolerated but killing them to protect property was acceptable.

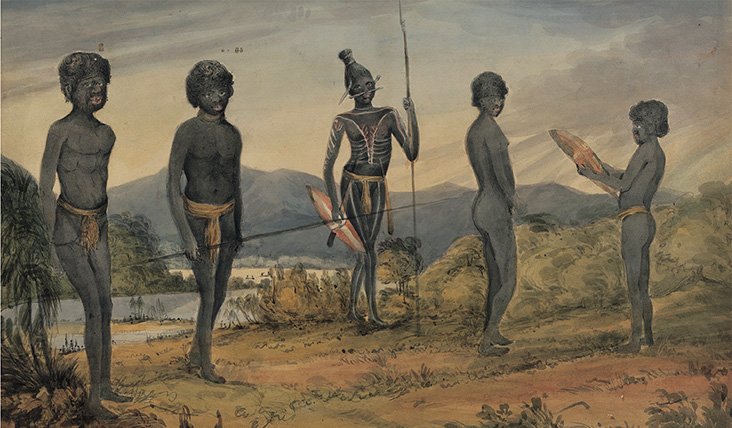

This drawing depicts Aboriginal people probably gathered to watch a fight, the man in the centre being one of the combatants. It is from an album of original drawings by Captain James Wallis and Joseph Lycett circa 1817–18, published 1821. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

By January 1795 Collins was reporting another European wounded by the wood tribe at the Hawkesbury. Historian Jan Barkley-Jack suggests the man may have been ex-convict settler Joseph Burdett whose grant was remote—at the most southern end of a row of grants on South Creek. If it was Burdett, he later died of his wounds. His land grant was reissued to Corporal Farrell, a Hawkesbury soldier who later gave evidence in the trial of the five Hawkesbury men.31

Collins mentions it only secondary to other violence, this time not directed towards Europeans, but among the Aborigines closer to Sydney. Two native women were murdered one night, another shockingly attacked and raped by several men in what Collins presumed was inter-tribal violence.32 In the same period, in the farming districts, several young Aboriginal boys happily worked with the hoe preparing the ground for grain crops. As encouragement or perhaps in payment, two or three of them received government rations.

The colonists in Sydney and all farming districts must have been aware their relationships with Aboriginal people were inconsistent from one area to another, and from one tribal group to another. There was no overall leadership between the tribes, no one group representing all. In Sydney, Aborigines sought friendships with the townsfolk while settling their own inter-clan or personal disputes in their usual manner. That could take the form of a vicious attack, particularly on their own women who would suffer damaging blows from their menfolk, blows that were often directed to the head. If there was a dispute between men it was sometimes settled by traditional fighting in which honour was at stake, the honour of both the wrongdoer and the wronged. At an appointed time the fight would begin with the combatants’ bravery on display before witnesses. In Sydney these fights became something of a spectator sport, with both colonists and Aboriginal people watching with interest.

Keeping the peace between settlers and the local Aboriginal community was only one of the challenges for the officers charged with running the colony. New South Wales was, after all, a place of banishment, a penal colony, but one which was expected to become self-sufficient. The gaol in Sydney, and the gaol gangs there and in Toongabby, were used to control and punish the worst characters. Most convicts were not in any gaol but were assigned to a government work gang, or to officers or settlers. Those in work gangs could be readily recognized by their clothing, known as convict slops: a striped cotton shirt and loosely fitting trousers made of calico, duck or canvas. But those in assignment were often indistinguishable from free people. Outside the towns of Sydney and Parramatta there was little or no government supervision. Soldiers of the New South Wales Corps were stationed in Sydney and Parramatta but the farming districts were generally without military or administrative oversight. It was impossible to ensure any of the Governor’s orders were received, understood and obeyed by the people in those districts. Assigned convicts often ran away. Some tried to leave the settlement all together, to escape to China, believed to be just over the mountain or down the coast. The theft of a boat, supplies and arms most often ended in the return of half-starved men dragging themselves back to the settlement. Very occasionally, escapees were rescued from certain death through being accidentally discovered at some remote location. Hiding on any ship that was about to depart the harbour was the most favoured escape ploy. Others took to their heels and ran away to the Hawkesbury settlement. Collins believed the settlers there were sympathetic and likely to harbour the vagabonds.

A first move to bring some control measures to the Hawkesbury came in January 1795 under Captain Paterson’s orders. Francis Grose had departed the colony in November and the next in command in the New South Wales Corps, Captain William Paterson, had taken interim command. He fully expected the next governor, naval captain John Hunter, to arrive back in the colony any day. In late January Paterson sent the colonial schooner, the Francis, to the Hawkesbury with provisions for the settlers and a grain mill for their use. A storehouse was to be built so the government could receive corn and wheat harvested on the farms. On board was a military guard, their officer instructed to ‘introduce some regulation among the settlers’. The authority of this presence was to prevent, according to Collins, more ‘enormities which disgraced the settlement’.33 By ‘enormities’ he was probably referring to the cruel treatment of the Aboriginal boy four months earlier. Sergeant William Goodall was probably the non-commissioned officer on board the Francis who was sent to take charge. He and ten privates formed the detachment left at the river.34 Until a commissioned officer was posted, Goodall received his orders in writing, from time to time, from Captain John Macarthur at Parramatta. The Francis carried materials and craftsmen to build a wharf and small storehouse, both of which were completed within a couple of weeks. The schooner then landed the provisions and put them under the care of the newly appointed storekeeper, William Baker.

There were also more officers, of both the military and civilian sort, on board the Francis. They had made the excursion to the Hawkesbury for the purpose of selecting eligible spots for farms for themselves. They looked around the river settlement and admired the luxuriant growth of the Indian corn. On return to Sydney they gave glowing reports of the state of the crop, the potential for excellent yields, and the picturesque appearance of the farms with well-stocked kitchen gardens.35 They selected the section of the river just upstream from the Argyle Reach. It came to be called Freemans Reach. Along each bank surveyor Grimes marked out 25-acre grants for ordinary soldiers. These were blocks that the officers would purchase and consolidate into larger holdings. The Judge-Advocate, David Collins, was one of those participants and he may have been on the Francis on that excursion. Certainly the commissary officer John Palmer was part of the group. Palmer, Collins, William Baker, Edward Abbott (military officer), John Livingston (civil officer), and John Stogdel (ex-convict in business with John Palmer) all availed themselves of the opportunity to purchase and consolidate parcels of soldiers’ grants. The sales were signed-off by the acting governor a few months later.36

It was the start of a significant increase in both the number of grants and settlers in the upper Hawkesbury River district. Coincidentally there was an increase in convicts receiving their freedom at the end of their sentence. Some of these people started travelling to the Hawkesbury area for work. At this time there were around 400 people at the Hawkesbury, the farms extending for twenty miles along each side of the river.

In March, Aboriginal men killed a second Hawkesbury settler. He was Thomas Webb, a First Fleet seaman who had returned to Sydney as a settler on the Bellona, the same ship bringing Edward Powell, Elizabeth Fish and the Rose family. Webb abandoned his farm at the Liberty Plains area to take up a more promising grant several miles downstream from the Windsor Reach. Unfortunately he was more isolated and vulnerable there. He had barely begun the work of clearing his land when Aborigines plundered his hut and then followed up with a personal attack that left him badly wounded. Webb was unable to recover and died from his wounds some weeks later, probably in Sydney as it was there he was buried.37 His headstone gave a message to his brother Robert, a farmer settler in Parramatta.38

In Memory of

Thomas Webb

Who departed this life May 1795

Forbear dear Brother

Weep not in vain

On Hawkesbury banks

By Natives I was slain

Webb would not have had a crop to pick, but many others did. The corn harvest was soon under way and it was a good one. In late May the colonial schooner was loaded at the Hawkesbury settlement with 1100 bushels of good quality Indian corn to carry back to Sydney.39 About the same time a group of soldiers were travelling up the river in a small boat when an Aboriginal man threw a spear in their direction. It failed to find its mark and so may well have been just a warning. Not so for two other men farming on Canning Reach almost opposite Thomas Webb’s farm. Joseph Wilson, ex-convict settler, and his labourer, a freeman named William Thorp, were gathering in the cobs when a large party of Aborigines attacked. Whether they resisted and surrendered their harvest to the raiding party is unknown, but they both died at the scene. What they faced was not an uncommon occurrence when corn was ripening in the fields. The natives would, according to Collins, arrive in a large group with blankets and nets to carry off the cobs, just as had occurred at Toongabby the year before. They ‘conducted themselves with much art,’ he wrote, ‘but where that failed they had recourse to force, and on the least appearance of resistance made use of their spears or clubs.’40

News of the death of Wilson and Thorp reached Sydney by road around the same time that Webb was being buried, 21 May. It was at this time that the acting governor decided to take further action to protect the Hawkesbury settlers. They were threatening to abandon their farms unless they received firearms to protect themselves. Paterson could not, and would not, issue the guns. There may also have been an element of pressure from another quarter in Paterson’s decision, as now there were officers’ farms to protect. Whatever the trigger, the officers believed that the attacks had reached a point that threatened the viability of the settlement at the river. In consequence, the grain supply for the colony was also at risk. Collins went so far as to call it a state of ‘open war’. To secure the farms and protect the settlers the military presence there (one sergeant and ten soldiers) was not enough. Paterson decided to send troops from Parramatta to drive away the natives. According to Collins the orders were specific:

to destroy as many as they could meet with of the wood tribe (Be’-dia-gal); and, in the hope of striking terror, to erect gibbets in different places, whereon the bodies of all they might kill were to be hung.41