Government House Sydney in 1802 or before, as depicted in the picture published by F. Jukes in 1804. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

10 The Politics – Governor Hunter, Mr Dore and the New South Wales Corps

England’s war with France made for delay in Governor Arthur Phillip’s replacement arriving in the colony. It meant that the senior officers of the New South Wales Corps were in charge for a total of nearly three years. When John Hunter received his commission as Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief of the colony the document was dated 6 February 1794.1 Yet his return to New South Wales was delayed a further nine months. At the time, a French invasion of England was expected any day. The British navy was on alert for action. The war in Europe had been going badly and agitation at home for a French style of liberty was threatening civil rebellion and upsetting the British government.

When in June that year there was some good news the government made the most of it. They wanted to believe the tide of war was turning in Britain’s favour. The Royal Navy had won a major victory over the French in the Atlantic, a victory that became known as the Glorious First of June. It was a cause for national celebration. The King and Queen, Prime Minister Pitt and his senior ministers all came down to Portsmouth to welcome home Admiral Howe and the fleet.2 Captain John Hunter was on the Admiral’s flagship, the Queen Charlotte, when the victorious fleet came in. Not having his own ship at the time, John Hunter had volunteered for service under his mentor who then placed him as post captain on his own ship.3

Finally allowed to set sail in the following February, Hunter arrived in Sydney on 7 September 1795 on board the Reliance. The acting governor, Captain Paterson, and the other officers, had been expecting Hunter’s arrival for months. It had been almost a year since they knew that the next governor was to be John Hunter. Hunter formally took up office four days after stepping ashore.

His first advice on the state of the colony would have been from the man holding the fort for the past ten months, Captain William Paterson of the New South Wales Corps. But Hunter’s more knowledgeable informant was his friend from the earliest days of the settlement, the ex-marine officer and the colony’s Judge-Advocate, David Collins. Collins had been there from the start. As secretary to the governors he was the right-hand man to all three before Hunter’s arrival—Phillip, Grose and Paterson.

Collins would have been as eager for news of home as he was to apprise Hunter of the settlement’s state of affairs. The turmoil back home would have been much discussed. But for Hunter, first priority was to understand the state of affairs in the colony. The place was very different to how he left it four years earlier. When Phillip sailed home the New South Corps took charge and with that change in power base many aspects of the administration altered. But Collins was ever the loyal civil servant and rarely revealed publicly his true feelings if they carried the taint of criticism. The personal opinions he shared with John Hunter, as far as they commented upon the irregularities in the administration of the two acting governors, he never committed to writing. Despite having received permission to return home two years earlier, Collins had been persuaded to stay in the colony to assist both Grose and then Paterson. But he was tired and wished to go home. The day-to-day duties of the law courts and assisting in the administration of the colony had been a heavy burden. David Collins had been indispensable—an adviser and confidant, much appreciated for his diligence and good sense. They all had the utmost confidence in him and so did the returning John Hunter. Hunter appealed to Collins to stay on, at least for a while, so he could find his feet.

Hunter needed to understand the lie of the land. The various farming settlements were now at some distance from Sydney and communication with the seat of government always took time. Sydney town itself had grown from the wharves at water’s edge to the Brickfields (today’s Central Railway area) with timber and thatched houses and small businesses, including grog shops, along each dusty street. Most of the people receiving land grants outside Sydney and Parramatta were ex-convicts. Almost everyone was still reliant on the government for food. Although the state of agriculture had advanced, especially on farms belonging to military and civil officers, it was at a heavy cost. The officers had set up their personal enterprises using many more convicts than the rules dictated. They had a labour supply at government expense, sold their produce to the government commissary, and continued to draw their military salaries. Many convicts had finished their sentence in the previous year and were now no longer available for deployment on government service. Almost nothing had advanced in the infrastructure needed to support the colony by way of new buildings, roadways, bridges, and boats. And the maintenance of those works in place when Phillip left had been neglected. With corn and wheat crops to be harvested in the following months the storehouses were too few and too small. The colony was awash with imported spirits and wine, and robberies were occurring almost every day and night. There was a shortage in the civil establishment through sickness, death and departures, and key officers, such as the commissary, wanted to go home. The situation with the military was similar. Paterson would have quickly made it clear to Hunter that the New South Wales Corps was somewhat depleted, both in total numbers and subordinate officers. As incoming commander-in-chief, Hunter’s arm-of-control in the colony, the military, were not up to strength. On top of this, Paterson himself wanted to go home.

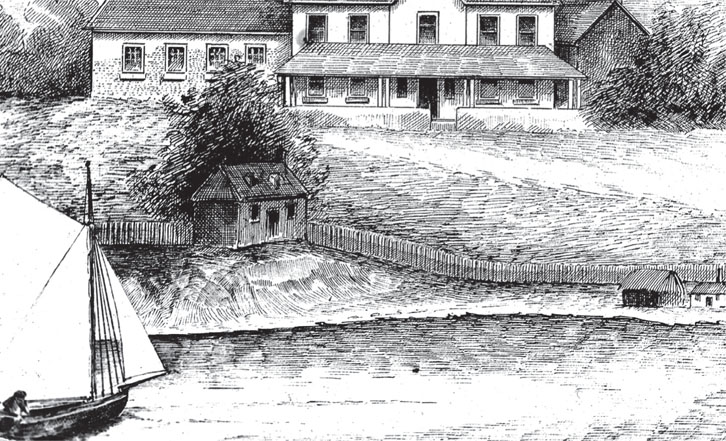

Government House Sydney in 1802 or before, as depicted in the picture published by F. Jukes in 1804. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

Government House Sydney drawn by an unknown artist. This represents the building as it was circa 1804. Courtesy of the Royal Australian Historical Society.

Parramatta was the second mainland hub of the colony and John Macarthur, by then a captain, had been in charge there. He was the regimental paymaster and Acting Governor Grose had given him an additional role, a civil rather than military one, as Inspector of Public Works. Together, these positions gave him a great deal of control over the colony’s resources of labour and materials. Macarthur certainly had influence with the acting governors, both Grose and Paterson. Receiving a 100-acre grant at Parramatta in 1793 from Grose, he set to work making a productive farm. When Macarthur deployed convicts to work gangs he made sure his own farm had an ample labour force. He was the first landowner in New South Wales to clear 50 acres of virgin land for cultivation, an achievement that gained him another 100-acre grant from Grose.

View of part of Parramatta, drawn by J. Eyre and published by A. West in 1813. Government House Parramatta is on the far centre left. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

Macarthur was keen to gain the new governor’s approval, particularly for the private farming ventures of the military and civil officers, of which his own was the most shining example. He invited John Hunter to come and stay for a few days on Elizabeth Farm, his property at Parramatta. One of Macarthur’s chief detractors was Richard Atkins. He had great hopes of John Hunter being able to curb the irregularities of the military administration. When, on 24 September, Hunter arrived in Parramatta to take up temporary residence with Macarthur, Atkins made a comment in his diary. It was ‘ominous’, he wrote.4

Hunter was impressed with Macarthur, his farming achievements and those of the other officers. The season was good and the crops had a luxuriant appearance. He believed the colony would soon have an excess of grain above its needs. Despite clear instructions to the contrary Hunter decided to continue the practice of allowing ten labourers for agriculture plus three for domestic duties to each officer occupying farming land. He gazetted his generous decision as a government and general order on 15 October. Those who arrived the previous year as settlers in the transport Surprise could have five convicts; the superintendents, constables and storekeepers, four; and the settlers from free people, two.5 Macarthur had convinced him that farming in private hands would put the colony on a secure footing in the supply of grain. But the British Home Secretary, the Duke of Portland, was not at all happy, and he said so by return mail as soon as he read Hunter’s intentions.6 It was a plan for private enterprise at government expense and Hunter was under orders to cut government expenditure wherever he could. Portland thought he should be using the convicts to grow government grain and not to feather the nests of individuals, government officers in the main. Unfortunately, it was not until May in 1798 that Hunter finally followed Portland’s directions and ordered a reduction in convict labour to just two at public expense.7 It applied to everyone, the civil and military officers and to all other farming people. They could keep more than two, but it would be at their own cost. Hunter still generously allowed them to draw the requisite clothing and food from the government store for the upkeep of the extra convicts they decided to keep, and to pay the value of those items back in grain or pork.

It was not any disagreement over private farming that was the cause of a breakdown in relations between John Macarthur and John Hunter. It was Macarthur’s behaviour towards others that got him into trouble—his propensity to be obstinate and take personal offence in any disagreement and his inability to see the other’s viewpoint. Within a few months Hunter had developed his own opinions on how the colony should be run and those opinions ran counter to those of Macarthur. On 24 February Macarthur wrote a letter to the Governor resigning his position as Inspector of Public Works, complaining about a lack of support for the way he wished to ‘regulate his district.’ His difficulties, he said, also came from ‘the loss of that confidence which your Excellency was once pleased to express’.8

Macarthur’s withdrawal was all the more bitter when he saw that it was Richard Atkins whom Hunter appointed to take his place. Macarthur and Atkins detested one another. Six months later a quarrel between them escalated to involve the Governor.9 It was a clash of wills that started over a soldier stealing turnips from the government garden. Atkins’ refusal to tell Macarthur the name of the soldier led to an exchange of vitriol between the two men that became a public dispute. In a fury Macarthur made accusations of dishonesty and drunkenness against Atkins, accusations that Hunter felt he could not ignore. Macarthur finally backed down from a threat to prove his list of allegations to a court of enquiry. But the attack on Atkins’ reputation then made it difficult for Hunter to give Atkins the job of acting Judge-Advocate after Collins sailed home. It was following that trouble that Hunter revealed some of his true feelings about Macarthur. He told the Duke of Portland that he had accepted, ‘without reluctance’, Macarthur’s resignation from the position of Inspector of Public Works. His opinion of Macarthur had plummeted and it was not just the quarrel with Atkins that was the reason. Hunter told Portland that he had not been long in the country when he realized that

scarcely anything short of the full power of the Governor wou’d be consider’d by this person as sufficient for conducting the dutys of his office, and that such power as he had thought proper to exercise having given cause to some complaints which had been laid before me, I saw it absolutely necessary to forbid any interference in the departments of other officers, who were respectively, as principals in their own departments, responsible to me as Governor. Such decision upon such complaints not having satisfied Mr Macarthur, he soon after desir’d permission to resign his civil appointment.

He went on to tell Portland that Macarthur realized that Hunter would come to his own decisions, and would not brook behaviour that annoyed people and worked against the peace and harmony in the colony.10

From that moment on Macarthur worked to discredit John Hunter at every opportunity and to have him recalled. He wrote a long letter directly to the Duke of Portland, when, if he had wanted to complain or give his opinions about matters, he should have done that through his own commanding officer and the Governor. He told Hunter that he was sending copies to the Duke of Portland of all the correspondence he had had with Hunter and he was intending to give Portland the benefit of his own opinions regarding the colony.11 Macarthur’s criticism of Hunter in that letter is scathing. In one paragraph he wrote:

I have declared that, unless our present errors are corrected, more serious difficulties will yet be felt; and I hesitate not to say, further, that the interest of Government is utterly disregarded, its money idly and wantonly squandered, whilst vice and profligacy are openly countenanced. I will not, however, substitute declamatory assertions for specific facts, as it is my purpose to convince your Grace that I am guided by a spirit of truth and influenced by a just sense of honour.12

This mode of operating towards the naval governors of New South Wales became something of a habit with John Macarthur. But the whole matter had rattled Hunter to the extent that he felt obliged to write to Portland himself with his own explanation of Macarthur’s troublesome nature and his impertinence in writing direct.

One of Hunter’s first actions was to reappoint the civil magistrates. Grose had replaced them with his military officers who then, alone, dictated the answers to most disputes in the colony. It had meant that the officers were not necessarily impartial in matters involving their own soldiers, with the result that justice was not always even-handed. With the military in power it gave soldiers and officers a greater licence to act in an irregular fashion when it suited their personal aims. But a simple reinstatement of the civil magistrates was not likely to change some accustomed bad habits. Hunter’s determination to deal with everyone in a fairminded manner was not to be as straightforward in the acting out as it should have been.

In October, just one month after he arrived, the high-handed ways of the New South Wales Corps were challenged in the civil court before Judge-Advocate David Collins. Soldiers had assaulted John Boston, a free settler. One of Boston’s pigs, a large pregnant sow, had got into the yard of Captain Foveaux, and was then shot dead by a soldier. When Private William Faithful shot the pig it was on the direction of the Quartermaster, Thomas Laycock. Boston ran to the yard, saw his dead pig and angrily called out the culprit as a ‘rascal’ or ‘damn rascal’. Laycock took that as an insult to any soldier and ordered Private Faithful to give Boston a ‘threshing’. Faithful hit Boston to the ground with the end of a musket directed to the head. Ensign Neil McKellar and Private William Eaddy were also present and involved. The court found in favour of the plaintiff, John Boston, and against Faithful and Laycock. The two were ordered to each pay 20 shillings to Boston for the loss of his pig.13 Boston had wanted £500 in damages, so the size of the penalty must have been disappointing. Nevertheless it was a censure, the first of its kind, albeit not very severe, against unruly behaviour by the New South Wales Corps. Private Faithful appealed to ‘a higher court’ to overturn the decision, perhaps not understanding that in New South Wales the only higher court was the Governor. But Hunter agreed with the court’s verdict. He thought that some officer had foolishly pushed Faithful to make the appeal. When Hunter reported the business back to London he expressed a hope that the case would impress upon those involved ‘a due respect for those laws by which everyone in this colony is protected in his person and property’.14

A more serious incident occurred four months later, in February the next year. A group of soldiers took it upon themselves to take retribution on a man who had reported one of them slacking off from duty, leaving his sentry post. The victim was John Baughan, a skilled carpenter and millwright. Having served out his seven-year sentence Baughan and his wife were living in a small neat cottage he had built near Dawes Point. The riotous soldiers stormed the cottage, demolished the building and its outhouses. They smashed up the furniture while holding Baughan down with an axe at his neck. The vandals then departed the scene cheering, as if something good had happened.

This grossly offensive behaviour could not be tolerated. It was a disgrace upon the regiment and a threat to peace and stability in the colony. Hunter intended to try the soldiers in the criminal court and he prepared a warrant for their arrest. But Captain John Macarthur appealed on behalf of the soldiers and asked Hunter to withdraw the warrant. He maintained the soldiers were contrite and that they would indemnify Baughan against his losses. Baughan himself, fearing further retribution if he did not agree, said he did not want the matter to go further. Hunter withdrew the warrant, although he later regretted doing so. It was an opportunity to punish the soldiers’ outrageous behaviour and the Governor, weakly, let it go. When Hunter explained his reasons to the Home Secretary, Portland was unimpressed. He told Hunter he could not imagine any justifiable excuse for not bringing the four soldiers to a court martial. He told Hunter that they should have been punished with the utmost severity.15

Hunter later heard that Macarthur’s part in this incident was hardly honourable. One of Sydney’s magistrates, surgeon William Balmain, apparently went to Baughan after the attack and questioned him. Balmain pressed Baughan to bring charges against the soldiers but Baughan was afraid to do so. When Macarthur heard what Balmain had done he challenged him with ‘malevolent interference in the affairs of their corps’. In an exchange of letters the dispute between Balmain and Macarthur escalated, almost ending in a duel. When Balmain later related the story to the Governor, Hunter felt compelled to write a memorandum about the incident.16

A few months later, in June, there was another incident revealing the superior attitudes of the New South Wales Corps officers. Richard Atkins reported it in his diary as ‘a very serious matter’ between himself, acting as magistrate, and the commanding officer at the Hawkesbury. When Atkins sent for a Hawkesbury man and woman to appear before him Captain Abbott told him that the woman was a soldier’s wife and he stopped her from going as he ‘saw no reason why she should be made a prisoner’. Governor Hunter became angry about it when Atkins told him of the incident. Hunter wrote to Abbott and threatened him with prosecution if he tried to interfere again. Atkins was pleased with that outcome. The military needed putting in their place. He added the following to his diary entry: ‘Thus at last the civil power appears to have shaken off military fetters. It is full time.’17

John Hunter’s adviser and confidant, David Collins, left the colony in August 1796. New South Wales would need a new Judge-Advocate and Hunter would need secretarial help in his office. But the next Judge-Advocate, Richard Dore, did not receive his commission until September the next year and then he did not arrive in the colony until May the following year.18 In the meantime Richard Atkins acted in the Judge-Advocate position, and although Hunter counted Atkins as a valued friend, he was not capable of filling Collins’ advisory role in the Governor’s office. For assistance Hunter appointed an aide-de-camp from the New South Wales Corps, Captain George Johnston. Johnston was the new commander of the corps after William Paterson went home on sick leave. Johnston had been a marine soldier with the colony’s founding fleet, as had David Collins.

It was the naval officers that Hunter could always rely upon for complete support. People like John Shortland who had been with Hunter on the Sirius coming to Australia and also when that same ship was lost off Norfolk Island. Shortland had sailed with Hunter back to England and then returned with him as first lieutenant on the Reliance. Henry Waterhouse, chosen by Hunter as second commander of the Reliance, had been in the Glorious First of June naval battle. Matthew Flinders also saw action in that naval operation before transferring to the Reliance. There was also George Bass, an experienced naval surgeon and navigator, much interested in exploration in the Pacific. When he heard the Reliance was being fitted out for New South Wales he obtained a transfer to her. William Kent was commander of the Supply, the ship that accompanied the Reliance to Australia. He was Hunter’s nephew—the son of Hunter’s sister Mary. When Hunter began his duties as Governor of New South Wales in 1795 he was 58 years of age. His experience had been entirely as a serving naval officer. The navy men who could support him were young in comparison. John Shortland was 26, Henry Waterhouse 25, Matthew Flinders 21, George Bass 24 and William Kent 35. The man who became his sworn enemy, John Macarthur, was then 28.

The naval officers had other things to do besides helping out the Governor. They were responsible for those few ships that were to stay in Port Jackson to bring supplies to the colony from distant places—Norfolk Island and the Cape of Good Hope. Those ships were the lifeline for the Norfolk Island settlement. But more importantly the naval officers were charged with surveying coasts and rivers of New South Wales and making detailed maps for the admiralty. The careers of George Bass and Matthew Flinders in that endeavour are still much celebrated. It was under Hunter’s direction that they made their brave expeditions. These were assignments that Hunter himself would have relished. He would have felt much more comfortable navigating the coastline—taking bearings of the headlands, sounding the depths—than he did wielding power in Sydney. When the naval officers were in Sydney they saw to the repairs of their ships and were able to devote time to any land-based duties as the Governor directed. Hunter would ask them to serve on the jury in the criminal court. However, the officers of the New South Wales Corps outnumbered their naval counterparts and so the criminal court often had a majority of military men, or even only military men, on the judicial bench.

When Richard Dore, accompanied by his young son, finally arrived on 18 May 1798 John Hunter was most welcoming. Dore was in poor health after the voyage and Hunter went to some effort to make him comfortable. In those first weeks Hunter invited Dore to dine with him in Government House every day until he was settled. He also gave Dore the bookshelf and desk that Collins had used, preserved by Hunter for the new Judge-Advocate.19 Within a few weeks Dore offered himself to Hunter as private secretary, no doubt after learning of the dual roles Collins had played. Hunter was happy to accept the offer and the appointment was announced in a general order dated 22 June 1798.

A few months later, Hunter found himself having to address complaints made to him against Dore. For the record, Hunter wrote to Dore asking him for an explanation ‘upon the subject of certain fees and demands’ made from Dore’s office.20 Dore replied he believed he was within his rights charging people for services and he justified his actions as being normal professional practice in England. Matters such as a letter of administration, or probate of a will, attracted a fee of ten shillings. When people wanted court action for non-payment of a debt the charges went up according to the size of the debt. For small debts he conducted a Saturday Court of Petty Sessions and charged one shilling for issuing a summons for recovery of a debt under £5, and two shillings for amounts over £5. Poor people did not go without the service if they could not pay, Dore said.21

When Dore took up office the civil court was busy hearing cases brought by creditors for unpaid debt. Civil court hearings had increased during the first couple of years of Hunter’s governorship. People finishing their sentences were growing ever more numerous and with that, many more people were conducting business transactions than ever before. These might be purchase of goods, payment of wages (often with spirits), sale of produce, rental agreements or sale of property. Most transactions were by way of promissory notes, particularly because of a lack of coin currency in the colony. A handwritten note promising to pay would be used as credit and often changed hands several times.

But the practice of charging fees for legal services was something new to the colony, and Hunter did not think it could be allowed. It was an imposition on the people. Permission for a schedule of fees would need to come from England, and they would decide on the amounts to be charged if they approved at all. Collins and Atkins had not added to their Judge-Advocate salaries in this fashion, although Dore claimed they had indeed done so. Frustrated by the Governor’s censure, Dore told Hunter he would rather quit his commission and return home than be barred from exercising those ‘trifling advantages which in some measure compensate’ for his toils.22

Richard Dore believed he should have the freedom to add to his salary while carrying out his commission. Perhaps that is not surprising, given that there were many in the colony at that time who had the same idea. He went too far, however, when he wrote himself one-third of moneys he collected for the issuing of 31 victuallers’ licences.23 The Governor intended the collected revenue for the building of a school for the colony’s orphans. Hunter would not abide Dore helping himself to money that was earmarked for the colony’s general benefit.

Hunter’s concerns about the Judge-Advocate had already deepened when, on 20 December 1798, two officers of the civil court complained about Dore’s behaviour that morning when the court opened for business. Richard Atkins and James Williamson were the officers scheduled to assist the Judge-Advocate on that day. They challenged Dore over the legality of a writ issued by him without the sanction of the court. Confronted in this direct way, Dore took offence. He told them he had the authority to issue the writs and the only explanation he would give would be to the Governor himself. With that he abruptly rose from his seat, took his hat and cane, bade them a ‘good morning’ and walked out of the building. The court broke up without conducting any business and without an adjournment in the normal manner. Atkins reported Dore’s conduct to the Governor as ‘highly reprehensible, disgraceful to himself, injurious to your Excellency’s authority, and insulting to ourselves’.24

Hunter was one governor who committed everything to the written record, whether he had secretarial assistance or not. He asked Atkins and Williamson to put an account of what happened in writing to him. He then wrote to Dore to challenge him on the matter.25 Dore not only continued to issue writs in this way but, unforgivably in Hunter’s eyes, he failed to answer the Governor’s letter. Atkins and Williamson again complained of Dore’s behaviour when the civil court met again. This time Atkins told Dore outright that the writs he had issued were illegal. To make sure Dore acknowledged this fact, Atkins entered a minute in the court’s proceedings noting the illegality of the writs and he and Williamson signed it. They told Hunter they believed that would be binding on the Judge-Advocate because he had no greater power than any other member of the court.26

Richard Dore, however, was keen to prove to the Governor that by his issuing the writs on his own accord he was oiling the wheels of legal practice for the benefit of the colony. He thought the best way to convince Hunter was to give proof of the support he had amongst the free and freed people in the colony, those who benefited by the civil court hearing actions against debtors in a timely fashion. Dore, or more likely his secretary, gathered no fewer than 70 signatures below a short statement about Dore’s innovative methods.27 Nonetheless the Governor would not agree.

Dore argued every point upon which Hunter tried to bring him into line. After an exchange of letters in late December it was obvious to the troubled governor that they had irreconcilable positions over their interpretation of the letters patent. The specific difference lay whether the civil court’s approval, that is, the agreement of the other two members of the court, was first required before the Judge-Advocate could issue a writ. Dore insisted he had the discretionary power and Hunter said he did not. No doubt perturbed by the man’s intransigence, Hunter decided he needed to solicit the opinion of others. He convened a meeting to investigate the meaning of the patent in question. Those present were the military officers Foveaux, Johnston, Macarthur and Prentice; the naval officers Shortland, Waterhouse and Kent; and the civil officers Alt, Balmain, Johnson and Marsden. In his statement to the officers on 15 January 1799, which he very likely read before the gathering, Hunter asked a series of questions and provided them with the original charter or patent. They all agreed with Hunter on the main point—that the writs should be made by the court when it is convened and not in advance by one person, the Judge-Advocate, acting alone. Once Hunter informed Dore of the officers’ opinions he reluctantly agreed to abide by the decision not to issue the writs on his own accord. It was a humiliation that Dore would not have taken lightly. To have all those men say he was wrong, without being present to defend his own opinions, gave Dore no way out except to admit defeat. To add to his humiliation Dore was to hear the rumours around Parramatta that Richard Atkins was shortly to replace him as Judge-Advocate. It was a rumour without basis, but nevertheless the way in which Hunter had censured Dore was harsh.

Dore’s acceptance of defeat was reluctant and not without a final barb. His opening paragraph in a letter to Hunter on 22 January reads as follows:

As no part of our correspondence on the subject of the Patent seems likely to remove the obstacles which have occur’d in the construction of it, I shall give your Exc’y no further trouble than merely to observe it appears rather extraordinary that the tenor and meaning of so important an instrument shou’d have been misconceiv’d for such a series of years, and by so many able and intelligent officers, and now only begun to be understood because the Judge-Advocate has in his professional character offer’d an interpretation of it which your Exc’y is not disposed to allow.28

A copy of Hunter’s final letter to Dore on this subject was included (as enclosure no. 17) with the letter of complaint he wrote to the Duke of Portland. Hunter was totally fed up with the whole story and that tone clearly comes through in the letter. He finished by saying ‘Our ideas seeming to differ so very widely in points of some consequence’. And this was the reason the Governor gave to conclude Dore’s employment as his personal secretary.29

It is interesting that he refrained for so long from dismissing Dore from a position requiring such a high level of trust and personal confidence. Hunter must have already doubted Dore’s integrity when two months earlier, on 9 November, he was preparing a duplicate copy of a despatch. Hunter noticed some extra sentences in his letter to the Duke of Portland that he himself had never written. The unauthorized paragraph lies within Hunter’s letter to Portland dated 25 May 1798. In it Dore attempts to ingratiate himself into Portland’s good opinion through fabricating Hunter’s good opinion of Dore:

It has given me the greatest satisfaction to find that your Grace has sent out a professional gentleman of the law in the capacity of Deputy Judge-Advocate to this settlement. Such a character was highly essential to the interests of this colony, and, independent of my personal regard for Mr Dore, I have, in honor of your Grace’s recommendation, appointed him my secretary, and he will in future have the regulation and direction of my dispatches to your Grace.30

On noticing the extra sentences Hunter immediately wrote to Dore stating that no such statement had been authorized, and that it was incorrect in any case as no such mention of Dore had been made to him by the Duke of Portland. Dore replied that Hunter had verbally authorized the statements, but in a further exchange of private letters between the two Hunter could not recall doing so.31

Hunter would have liked to send the errant Judge-Advocate home but he thought he did not have the authority to do that. He was very disappointed in Richard Dore. He had hoped for the kind of assistance and dedication to service exemplified in David Collins. Hunter explained to Portland that Dore’s intentions to do his duty for the good of the colony were diverted, soon after his arrival in the colony, by the influences of certain people. The result was that Dore actually aided the traders in pursuing their debtors. This was to the detriment of the farmers in particular, and the colony in general. Hunter surmised that it benefited Dore as it did the traders, as by paying Dore a fee for issuing a writ against a debtor he facilitated the trader’s success as he did his own. One consequence of Dore’s issuing writs for arrest in advance was that people were detained in gaol until the matter came before the court. In one case the detainee was a convict who was withdrawn from public labour on account of his failure to pay a debt, a debt that Hunter maintained he should not have been able to enter into. Hunter was concerned at the withdrawal of the man’s labour from the benefit of the colony, and all at the discretion of Mr Dore.

It appeared to Hunter that some people, unnamed, were playing a double game with the Judge-Advocate. The very people Dore considered his friends were the same people who, in other places, said his conduct was improper.32

The problems Dore was bringing to Hunter’s governorship were set to worsen in the following months. This time it was over Dore’s management of the criminal court. Hunter expressed his concern in another letter to Portland (dispatch 40) also dated in the Historical Records of Australia as 21 February 1799, but actually written between 6 April and 22 May. The issue was over the court having found Isaac Nicholls guilty of receiving stolen property. Hunter told Portland that the dealers in the colony had influenced the Judge-Advocate to the extent that he was prepared to favour their malicious cause against Nicholls.33 Whether by mistake or design, Dore had admitted hearsay evidence without comment on its admissibility. The trial resulted in a verdict of guilty by four votes to three, the four being the three New South Wales Corps officers, McKellar, Hunt Lucas and Bayly, with Dore making the fourth and casting vote. The three not guilty votes came from the naval officers, Flinders, Waterhouse and Kent.

So there it was—a split between the officers of the New South Wales Corps and the Royal Navy, with Richard Dore aligning himself with the officers of the corps. Hunter was outraged at what he believed was a misuse of the court for the malicious purposes of the traders and their ‘ruinous traffic’. He refused to confirm the sentence—fourteen years’ transportation to Norfolk Island with work for government in the common gaol-gang until the time of Nicholls’ embarkation. In a style that had become all too familiar to the Governor, Dore, purporting to have the agreement of the other magistrates, ordered the sentence be carried out immediately. On Dore’s order Nicholls was chained and confined to gaol, without waiting for the Governor’s approval. As commander-in-chief, John Hunter had the executive responsibility to approve or disapprove a sentence of the criminal court. But Dore had sent Nicholls to gaol before the Governor’s wishes were known. It was an affront to the Governor’s position that Hunter felt sharply. He was still seething with anger when he wrote to the Home Secretary the following words:

This man, my Lord, has us’d the authority of the other magistrates without their knowledge to support his views of snatching out of my hands an essential part of the executive authority of the Governor. Your Grace I am convinced will pardon my expressing myself rather warmly upon such occasion, but I declare, my Lord, that had an opportunity been within my power I shou’d have order’d him to return to England. It is evident he is influenc’d by a party to act as he has done, and such appearances will be ever dangerous to the peace and tranquillity of the settlement. The people see the prevalence of such a party, and as many seditious characters are to be found amongst us, I conceive such appearance injurious to his Majesty’s authority and government.

Isaac Nicholls was chief overseer of government labour gangs in and around Sydney. Through diligent and reliable work since the expiry of his convict sentence, he had gained the respect and appreciation of Governor Hunter and Captain George Johnston, Hunter’s aide-de-camp. Dore had allowed hearsay evidence in the trial and Hunter thought that had unfairly damaged Nicholls’ defence. Allowing hearsay evidence was a practice that Hunter said would, if it continued, be the ruination of the colony as there were many disreputable characters ready to give it.

Hunter was so convinced there had been a miscarriage of justice that he held a court of enquiry into the evidence. The verdict of those men—four civil officers and one naval officer (Samuel Marsden, Thomas Laycock, James Thompson, James Williamson and George Bass)—is not given in the minutes of their proceedings. If it was that they confirmed the original majority verdict of guilty then it was of no use to Hunter. Perhaps this was the case—they had confirmed the original verdict—and is the reason Hunter did not use the royal prerogative and declare Nicholls pardoned. Hunter also asked the three naval officers who served in the criminal court to write down their views of the evidence. As they reviewed the trial proceedings it was clear to Waterhouse and Flinders that Nicholls could not have committed the crime when and how it was alleged he did. All three naval officers restated their belief that Nicholls was innocent and that much of the trial evidence was unreliable as it was hearsay.

Hunter assembled all the information to send to the Home Secretary. He was as thorough in his complaint writing this time as he had been about the matter of the writs. The documentation included a covering letter of his own, the Nicholls trial proceedings, minutes of the court of enquiry, the opinions of each of the three naval officers who served in the trial, and letters to and from the Judge-Advocate.34 Also included were the proceedings of the two other criminal cases and associated letters. Both cases were related to Nicholls’ arrest for receiving stolen goods.

One was the trial of John William Lancashire. He was found guilty in another split decision of the court. It was again a four to three verdict—the military plus the Judge-Advocate making four, the naval men three. But, unlike Nicholls, Lancashire’s was a capital offence, that of passing a forged bill. The split decision of four to three in a capital case meant the proceedings had to go back to England for a ruling. Lancashire petitioned the Governor for mercy and also wrote to Captain Kent asking him for help. In the letter to Kent he said that a junior military officer, one Ensign Bond, had come to him in gaol and pressured him to admit having given false evidence in the Nicholls trial, evidence that favoured Nicholls’ defence. If Lancashire admitted to receiving money from Nicholls in payment for the false testimony, then Captain Macarthur would take Lancashire’s petition to the Governor. It would, Ensign Bond promised, be the means of saving Lancashire’s life. But Lancashire refused to change what he had said in court.

Macarthur went to the gaol to follow up. He brought the Reverend Richard Johnson along as a witness and scribe for Lancashire’s confession. Macarthur promised he would ask the Governor for mercy on Lancashire’s behalf if he signed a statement admitting false testimony to protect Nicholls. But Lancashire again refused to go along with it. Reverend Johnson later wrote to Hunter explaining what happened and saying that he himself was not party to Macarthur’s intention at the time. He had gone along at Macarthur’s request out of thinking it was his duty.35

It seems that Macarthur tried to intervene to get the outcome he wanted. This time it was in an effort to revise the evidence in a way that supported Nicholls’ guilt. His motives were never spelt out in the historical record but the fact that he made an attempt to interfere appears to support Hunter’s opinion that Macarthur was involved in a plot to get rid of Nicholls. Nicholls’ original seven-year sentence for stealing had expired in 1797 and, as a free man, he was on his way to establishing business ventures. He had already begun farming in the Concord district with the assistance of two convict workers allowed to him instead of a salary as an overseer. He had also obtained a spirit licence and opened an inn on busy George Street, Sydney.36 On the road to business success, a clash with those parties in Sydney involved in trading spirits was certainly a possibility.

The other March trial record that Hunter sent back to England was that of William Collins.37 He was the unlucky one of four men charged with the capital offence of breaking into a warehouse and stealing a large quantity of tobacco. (Nicholls was supposed to have later received the stolen tobacco.) Collins was found guilty with a vote of five to two, a sufficient majority for sentencing. This time one of the three naval officers on the bench, Matthew Flinders, had given a guilty verdict when his two naval colleagues had voted not guilty. But Flinders did not think the crime warranted the death penalty and he said so when he gave his vote. The Judge-Advocate and the other three officers—military officers— wanted the death penalty. As Flinders was out of step on the sentence Dore referred the matter to the Governor. But Hunter said it was a matter for the court to decide. Dore interpreted Hunter’s answer as giving him the freedom to finalize the matter. He handed down the death penalty to Collins regardless of Flinders’ previous objection. Hunter nevertheless decided to stay the execution and to send the trial proceedings back with the others for the review of the law officers at home. Even though five out of seven had voted guilty (the requirement for sentencing in a case of a capital offence), only four had voted for the death penalty. Hunter therefore withheld his confirmation of the sentence and instead referred the matter for others to decide.38

The whole matter was a mess that had taken up a great deal of time for all concerned. Hunter was getting nowhere in curbing the officers trading in spirits and now it seemed that justice in the courts could also be perverted to their ambitions. The Judge-Advocate had shown a disregard for the legal protocols expected of him and a propensity to insult the Governor’s position by trying, in the Nicholls case, to deny him the prerogative of reviewing the sentence.

John Hunter had lost confidence in Richard Dore and Dore knew it. The bare fact must have demoralized the Judge-Advocate. No doubt Dore’s ill health also ate away at his readiness to apply himself to a hefty workload. In his correspondence with Hunter, he pleaded innocence of purpose and surprise at being misunderstood. In his last letter to Hunter regarding the latter’s decisions to send back the proceedings of all three trials he expressed his hurt and resentment.39

I have observed of late, with much concern, that the style of your Excellency’s letters to me has not been such as I conceived myself entitled to, whilst rectitude and Integrity were the leading principles of my conduct – far from ever having a thought of offending you, Sir, either as Governor of this territory, or a private Gentleman, I owe I am at a loss to discover from whence your prejudice (or perhaps your displeasure) has originated – nor had I the most distant Idea when I came into this Territory that I should in my Official Situation meet a style of language here which I have been wholly unaccustomed to in England.40

The New South Wales Corps officers serving on the bench in the Nicholls trial were more confronting with Hunter. Richard Dore had told them what transpired when he met with the Governor about the Nicholls case. He had told them the Governor wanted a copy of the trial proceedings and was going to hold a court of enquiry into the verdict. No doubt Dore was annoyed. As he related Hunter’s intentions he may have embellished the facts, as the officers reacted angrily. In the letter they wrote to Hunter, they—McKellar, Hunt Lucas and Bayly—took umbrage. They were offended that Hunter thought they had not diligently carried out their role as officers of the court.41

They objected to Hunter making criticisms of their verdict. They said he had made ‘animadversions’ (meaning remarks by way of criticisms or censure), and they repeated the word in a haughty defence of their own integrity. They claimed he had ‘harshly and unjustly treated’ them. They said the court of enquiry had confirmed their own verdict—that Nicholls was guilty. The minutes of the court of enquiry, however, did not actually include any final decision. The fact that Hunter did not dispute what the officers said seems to indicate that they were correct—the court of enquiry had confirmed the guilty verdict.

The three officers insisted their letter be also sent back to London with the trial proceedings, the minutes of the court of enquiry and every other relevant document. Their final rejoinder perhaps did make Hunter think twice. They said they hoped that Hunter’s intervention, using his executive power,

may not be productive of dangerous consequences, and in future form a restraint upon officers who may be called upon to sit as members of a Criminal Court, and may induce criminals to persevere in their iniquitous practices, by observing the differences which so unaccountably arise between the judicial and executive power.

At this point in his governorship, April 1799, Hunter was in real trouble. His letters to Portland, almost from the start of his term as governor, plead his difficulties in gaining control of the problems that beset his administration. In the following few months Hunter was dogged in compiling all the relevant documents to his current problems. It made for evidence as much in defence of his own actions trying to stop a miscarriage of justice as it was about showing Portland the resistance he faced in trying to do so. The only direct support he could muster appears to have come from the naval officers who served as members of the court. There would have been serious discussions in Government House between Hunter and his naval colleagues Waterhouse, Kent, Flinders and Shortland over the conduct and attitudes of the Judge-Advocate and the New South Wales Corps officers involved in these trials. The naval officers stood by John Hunter and supported the process he took over the whole affair. No doubt they agreed that if he laid the whole mess in front of the Secretary of State the Governor’s actions would be vindicated.

But if Hunter was looking for an understanding and sympathetic ear from the Duke of Portland, it was too late. It was success Portland wanted from Hunter. The Governor was there to use his position of power to tackle and solve the problems, not to bleat about how difficult he found them. John Hunter was not to know that Portland had already made up his mind to recall him, although he did not write to Hunter about that decision until November that year.42

As Hunter was battling over the Nicholls case, the Duke of Portland was considering a letter of complaint about Hunter’s administration. It was an anonymous letter but from someone in New South Wales with credibility. It claimed that the price of necessary goods in Sydney had lately doubled; that the military officers were purchasing spirits and goods and retailing them at exorbitant prices to settlers and convicts alike; that the same kind of traffic was carried on from Government House although the Governor himself was not accused; that officers and favoured individuals were given preference in depositing large quantities of grain into the store while those producing small amounts were refused and forced to sell at low prices to hucksters. Portland wrote to Hunter asking for an explanation.43 Those assertions were hurtful to Hunter’s reputation with the Home Office. They were, however, based on fact and Hunter had an anxious time, when he finally received the letter, in defending himself. His own steward, Nathaniel Franklyn, had been trading rum out of Government House during times Hunter was away in other parts of the colony. When Hunter investigated and the matter became public, Franklyn, sadly, committed suicide.44

A few months after the Nicholls debacle, in October, the criminal court met to hear the case of the five Hawkesbury men charged with killing two natives. When Hunter sent the proceedings back to London for review he also sent back the records of two more trials.45 One was the trial of a man named Chapman Morris, charged with forging a note for payment of £23 over the signature of the man in charge of the Commissariat, James Williamson. Morris was found guilty of the forgery but it was another split decision—four guilty to three not guilty. The trial took place on 16 and 17 December 1799, but this time it was with six New South Wales Corps officers sitting on the judicial bench together with the Judge-Advocate.46

The prosecution was based on James Williamson’s opinion about the promissory note. But the defence testimonies cast doubt on the reliability of Williamson’s memory regarding this and other transactions. The Reverend Samuel Marsden gave evidence that a man had told him that Morris had forged the note. It was hearsay evidence and the Judge-Advocate allowed it. Richard Dore did not comment on, or rule out, the admissibility of Marsden’s testimony. Again he was ignoring the hearsay rule. Morris was very thorough in his own defence, bringing witnesses who showed that Williamson’s testimony was unreliable. Although the officers’ deliberations were never included in the record, it does appear that Richard Dore did not show the leadership required regarding admissibility of evidence. Perhaps that factor led to the verdict being split.

The other trial sent back by Hunter was held on 16 December immediately before the Chapman Morris trial and the same officers served on the bench. Two mates belonging to the transport ship Walker, George Parker and Nathaniel Marshall, were charged, at the Governor’s request, with ‘Disobedience of His Excellency’s Port Orders, obstructing an Officer in his Duty and other misdemeanours.’47

Governor Hunter had placed one of his own boatmen, a convict by the name of John Roycroft, on watch from a boat alongside the Rocks area of Sydney Cove. He was to watch that no spirits were landed from the Walker without a permit. If an attempt was made he was to seize the spirits. Early on Sunday morning, about one or two o’clock, Roycroft saw a boat going ashore and hailed for it to stop. But it did not and Roycroft followed as it went back out to the ship. He caught up as it reached the side of the Walker. A cask was being hauled up into the ship. Roycroft reached over the side of the boat and laid his hand on two casks, announcing that he was seizing them in the King’s name. He was sure they contained spiritous liquors. By rubbing his hand over the bungs of the casks he confirmed it. When Roycroft announced it was gin, one of the two sailors, Parker, called for pistols. Parker threatened Roycroft that if he did not go from alongside he would ‘blow his brains out’. Understandably, Roycroft quit the scene and rowed ashore without the casks.

He must have reported the incident and identified the two sailors to the Governor as Hunter had them arrested and charged. Other witnesses were called but their evidence is missing from the HRA account of the trial. Parker and Marshall pleaded the evidence was circumstantial since there was no proof that liquor was in the casks, or that they had attempted to land them. They said Roycroft was incapable of providing evidence as he was a convicted perjurer with a sentence of seven years. The fact of his crime and sentence was admitted by Roycroft to the court and confirmed by the Provost Marshal.

The master of the Walker showed the court a copy of the ‘Charter-Party’, the document of agreement between the ship’s owners and the Ministry of Transport. The document specified that the master and crew would not land any spirits or other commodities in New South Wales without a permit from the Governor. A penalty of £1000 could be recovered in the case of a breach of the agreement.

The court was cleared and the officers on the bench, Captains George Johnson, John Macarthur, John Thomas Prentise, Lieutenants John Piper and Anthony Fenn Kemp, Quartermaster Thomas Laycock, and the Judge-Advocate Richard Dore, deliberated over the evidence. Their conclusion was that there had indeed been an attempt to land spirits, in a clandestine manner, from the Walker. They believed there was ground for action against the ship’s owners for a breach of the charter-party. However,

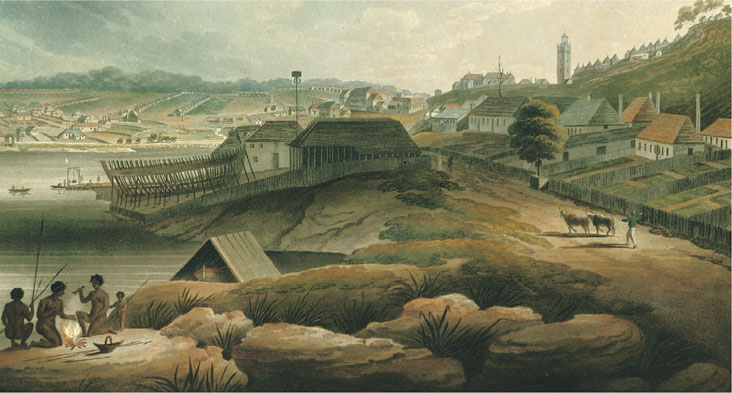

Sydney Cove as it was around the time of the attempted smuggling trial (December 1799). A government wharf is centre left. In the foreground are the rocks from which Governor Hunter’s boatman, Roycroft, set out in his rowing boat to intercept the smugglers. The courthouse has been identified as the building just below the row of convict houses on the far top right. From a picture drawn in 1802 or before and published by F. Jukes in 1804 with a key to the buildings. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

there was no Proof before the Court that Roycroft was regularly Authorized to make any seizure, and as the Manner of his going alongside the Walker, unaccompanied by any other Person, was extremely irregular and improper the Court acquit the prisoners.

This result does appear to be quite extraordinary. The officers and Judge-Advocate decided there was a case to answer but that the ship’s owners were the ones responsible. The court had the perpetrators there in front of them, but acquitted them. And the reason they discharged the two prisoners?—that the man Governor Hunter had placed on sentry to stop any smuggling of spirits was acting improperly. Surely if there was any doubt of Roycroft’s authority in this duty, the Governor, had he been asked, would have confirmed it. Instead the court decided there was enough evidence to fine the ship owners back in England, yet not enough to find the two mates guilty.

Why did John Hunter think he needed to place his own boatman on sentry duty to stop the smuggling of spirits? The only rational answer is because he had no confidence in any soldier of the New South Wales Corps being willing (given that their order would have to come from one of their own officers) to perform this duty. If the military were up to their necks in the trading in spirits, and they were, then they were not the ones who would stop the smuggling. Hunter’s only recourse was to place someone else, in this case one of his own boatman, under his own direct order to stop the spirits coming in. And what was the result? The criminal court mocked the Governor’s effort.

The court’s decision was in direct opposition to Hunter’s control. But Hunter’s surrender to their verdict seems meek. The account published in the HRA indicates that four other witnesses were called but it does not include their evidence. The microfilm record is more complete.48 Those witnesses were John Croft, a private in the New South Wales Corps; William Smith, another private in the corps; James Worth, third mate of the Walker; and John Sinclair who had been on the deck of the Walker. A fifth man, Cornelius Hemmings, was called but his evidence was considered inadmissible for a reason not given.

Privates Croft and Smith were on duty as sentries the night the encounter took place. Croft was at the government wharf and Smith at the storehouse nearby. Both saw the boat coming towards the shore from the Walker. Croft said that he challenged the boat but it did not stop. On hailing it a second time the boat put back to the Walker. He then saw Roycroft in pursuit in his boat. He knew Roycroft had been stationed there to watch the Walker. Smith gave a similar account and both soldiers said they heard a voice declaring ‘are you come to rob the ship’, ‘bring me my pistols’ and ‘I’ll blow your brains out’.

The Walker’s third mate, James Worth, was on the ship’s deck and he gave a similar account. He said there were five casks in the boat and believed them to contain rum, but he didn’t know who owned them. He heard but did not know who it was who uttered the call for pistols.

The fourth witness, John Sinclair, said he was on the Walker’s deck and he helped bring the casks up while the encounter with Roycroft was going on. The prisoner Parker had called for pistols and had threatened Roycroft. He didn’t know what was in the casks but estimated their capacity as about thirty gallons.

The evidence was clear that there had been an attempt to land spirits but that Parker and Marshall had put back to the Walker when they were challenged to stop. Nevertheless the court discharged the prisoners and called Roycroft’s attempt to carry out the Governor’s order as ‘irregular and improper’.

The officers must have congratulated themselves on outsmarting the Governor. Richard Dore had willingly gone along with them. Indeed John Hunter acknowledged they had the better of him. Not in his letter accompanying the trial proceedings back to London, for in that he commented only on the need to bring the case before the court. But in the letter to Portland one month later he admitted he could not stop liquor coming into the colony. Another ship, the Minerva, had arrived in Sydney carrying a variety of much-needed goods and a large quantity of spirits. The civil and military officers had chartered the ship to bring the goods without any knowledge or permission from the Governor. Once the ship had arrived in Sydney they told Hunter that the spirits were to pay the labour on their farms. Hunter told Portland: ‘To oppose it being landed, my Lord, will be in vain on my part, for the want of proper officers to execute such Orders as I might see occasion to give.’49

And so Hunter granted permission for the landing of all the goods, including 50 legars (the equivalent of 9000 gallons) of spirits.50 He accepted the officers’ argument that the supply of these moderately priced goods somehow cut across the monopoly that would otherwise result from ‘adventurers’. John Macarthur, William Balmain and James Williamson signed the letter requesting permission to land the goods. Perhaps Hunter thought the officers’ argument had some merit as he also received a petition from eighteen people, predominantly ex-convicts, asking permission to buy goods out of the Minerva. They quoted the prices they would pay, significantly less than in the past. Their list included butter, sugar, casks of beef and pork, glass, linen, shoes, rum and port wine. It is not clear whether the prices they were to pay were to the officers who owned that portion of the cargo or to the master of the ship.51

John Hunter had given up trying to control the importation of wine and spirits. Not only was he giving tacit approval for its importation but he was also purchasing the same liquor for the government store. It was to be used as part of the recompense to superintendents, constables, watchmen and other middleorder government men. That was the way things were done in the colony, similarly in the navy, and Hunter never attempted to change the practice.

Although Hunter did not know it, the Duke of Portland’s letter recalling him to England was already crossing the oceans to New South Wales.