‘Captain John Hunter.’ Engraving from a paintinh by R. Dighton. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

The Trial Outcome

This was the first time that white men were criminally charged, tried and convicted of wantonly killing Australian Aborigines. That the defendants were freed after having been found guilty has not only been an enigma but is a shameful blot on the history of black–white relations in Australia. Up to now historians have told the story only in part because the trial record does not reveal all possible about the context of events. The depositions taken three weeks before the trial are historical evidence utilized here for the first time. The correspondence between Richard Dore and Governor Hunter and an analytical approach to the criminal court records for 1799 led this author to a new conclusion—that the trial’s conduct and outcome were influenced by the breakdown in relations between Judge-Advocate Dore and Governor Hunter.

When David Collins was Judge-Advocate he did not write letters to the colony’s governors about his working arrangements with them, Governors Phillip, Gross, Paterson and Hunter. When two people are of the same mind on subjects of duty in which they have a common interest, there is no need to confirm their agreement with an exchange of correspondence. But when the two most important public servants in the colony did not agree, they resorted to writing to each other. The letters between John Hunter and Richard Dore provide evidence of a sequence of disagreements that compelled each to explain and defend his own opinion to the other. The disagreements were mainly over how far the Judge-Advocate could act independently of the Governor’s wishes. Whether it was in the matter of issuing writs, charging fees, or the verdict of the criminal court—as in the Nicholls case in particular—the conflict between the two is revealed in their letters.

For whatever reason lay in Richard Dore’s mind, he did not want to charge the five Hawkesbury men with the murder of two natives. So he wrote his note to the Governor. He asked John Hunter to tell him precisely under what government order could the charge of murder be established, or alternatively, what other offence did Hunter consider appropriate? Hunter’s reply spelled out the basis for a charge of murder. But Dore did not follow Hunter’s wishes. Having the independent authority to make the charge, he used wording the Governor had not envisaged. ‘Wantonly killing two natives’ was how he wrote it—a charge description that was not, and is not, recognized in law as a criminal offence. Using the words, but not the spirit of the government and general order of February 1796, Richard Dore gave the charge the appearance of something that contravened the Governor’s order. Dore never revealed his reasons, but it does not seem too much to conclude he intended the charge should be a less serious one than murder.

The New South Wales Corps officers played a part that is obscured from our direct view because the historical evidence necessarily focuses on the correspondence between Richard Dore and John Hunter, and between Hunter and his masters in London. That Richard Dore had, as Hunter put it, ‘taken party’ with the officers was undoubtedly true. The trial records for those cases referred back to London show that a difference of opinion repeatedly occurred between Governor Hunter’s naval colleagues and the officers of the New South Wales Corps, Richard Dore always siding with the corps officers. Governor Hunter sent to London the proceedings of five 1799 criminal trials because the jury could not agree over either the verdict (in three cases) or the sentence (in two cases). In one of those five, the Nicholls trial, the Governor intervened by holding a separate enquiry. Whenever the officers of the New South Wales Corps were on the same jury as officers of the Royal Navy their judicial opinions were at odds. In a sixth case Richard Dore and the jury of six New South Wales Corps officers believed that an attempt to smuggle liquor ashore from the Walker had been made. The men who had made that attempt were before the court but were discharged because the jurors said Governor Hunter’s watchman did not have the authority to intervene—to stop the smugglers. That decision was an open and blatant insult to the Governor’s authority. The New South Wales Corps officers and the Judge-Advocate were willing to manipulate the criminal court when it suited them to do so.

H.V. Evatt argued in his book Rum Rebellion that the vested economic interests of the officers defied the regulations of the governors of New South Wales because they had the monopoly on wealth, violence and justice.1 His argument was based on evidence, particularly from actions in the law courts during the lead-up to the overthrow of Governor Bligh, an event that took place in 1808. However, those subversive actions towards the governors started much earlier. Everett himself acknowledges the Nicholls case as demonstrating the ends to which the corps officers were willing to go in order to maintain their monopoly. It is now also clear from an analysis of the Walker smuggling case that they, together with Judge-Advocate Richard Dore, were willing to pervert the course of justice for their own ends.

We have no proof that any military officer influenced Richard Dore’s actions when it came time for him to charge the five Hawkesbury men with the offence of murder. Dore’s decision on the charge did not suit the Governor’s wishes but was more likely to have been in keeping with the preferences of his friends in the military. They would have been concerned that a murder charge could be brought when the settlers were avenging the death of two of their neighbours. Retaliation had been the common way of dealing with all kinds of problems from the Aborigines. Killing Aborigines was, unfortunately, commonplace. It is also apparent that the New South Wales Corps had only very recently protected one of its own soldiers from any repercussions after he killed an Aboriginal woman and child.

When the trial of the Hawkesbury five commenced, Richard Dore was fully aware that Hunter had discharged Aboriginal Charley from any punishment. He brought the matter up with the trial’s first witness, Constable Rickerby. The military officers would certainly have disapproved of Hunter freeing Charley— Lieutenant Hobby had sent Charley to the Governor for punishment, not for a verbal admonishment. In their eyes Hunter’s handling of the matter had been disappointingly weak. Allowing Charley to again be at large was, according to Lieutenant Hobby, risking the safety of the Hawkesbury River farming community. Richard Dore agreed. During the trial he set about exposing Hunter’s dubious handling of the Charley affair through the testimony of Lieutenant Hobby and then Corporal Farrell. Dore, together with jurors Macarthur, McKellar and Davis, knew the trial record itself could be used to damage John Hunter’s governorship. That is likely to be the reason they wanted the trial record sent back to London. Since the court agreed on a guilty verdict there was no formal reason to refer the case for review. If they sentenced the five men the case would be finalized in the colony. Furthermore, if the jurors were divided over the severity of the sentence the Governor would ask the court to make a decision—as he had in the Collins case. Hunter would still then have the prerogative to reduce the sentence if he thought it necessary. The trial record would stay in the colony, unscrutinized. The only way of ensuring the case was read by the men in the Colonial Office in London was for the court in Sydney to directly make that decision. And that was what Richard Dore and the three officers did when they voted, in unison, to send the case back for review.

The other element that no doubt influenced the corps officers in their decision, and perhaps also the Judge-Advocate, was their wish to simply frustrate Hunter’s administration. It was a declared aim of John Macarthur’s to do so. To curtail Hunter’s plan to make an example of the five Hawkesbury men was to notch up another mark in the failure of John Hunter as governor of New South Wales.

Who Killed Jemmy and Little George?

The political machinations that explain the trial outcome shed no light at all on what happened when Jemmy and Little George lost their lives. The trial evidence shows conclusively that their murder was an act of revenge by a group of settlers on the Argyle Reach of the Hawkesbury River. It was in retaliation for the recent murders of Thomas Hodgkinson and John Wimbo by Aboriginal tribesmen, associates of these young Aborigines. Once the widow Hodgkinson had identified the three Aborigines who were in Isabella Ramsay’s house as being amongst those who had agreed to accompany her husband on the hunting trip, some kind of response was inevitable. When Constable Powell arrived home, Sarah Hodgkinson was quite definite about what should be done—they should be killed. At Isabella Ramsay’s house the number of visitors grew. They were there to see Hodgkinson’s killers. Whether these three were the actual culprits seemed not to have mattered. If Metcalfe and others actually did advocate finding the real killers by using these three to confront the clan, their advice fell on deaf ears. The mob bundled the three Aborigines outside, in all probability with the intention of hanging them. Before that could be accomplished the eldest broke free and ran away. With the other two struggling and calling out, immediate action was needed. They were killed on the spot.

But precisely who fired the muskets and wielded the cutlass is not so obvious. Historians have so far assumed that the men charged with the offence and found guilty were those who committed the crime. They have used three sources of evidence about what happened. They are: first, the trial record itself; second, Governor Hunter’s January 1800 letter to Lord Portland with which he enclosed the trial transcript; and third, six paragraphs in the second volume of David Collins’ book An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales. Those paragraphs describe, in condemning terms, how and why the trial came about and how the case was referred back to London. John Hunter wrote those paragraphs, although, to date, that has not generally been acknowledged by those writing about the subject of these murders.

A fourth source of evidence is the depositions. These are the statements taken from witnesses six days after the murders and three weeks before the trial. The depositions are an additional source of evidence evaluated in the writing of this book. As some of these deponents gave evidence in the trial itself, a comparison between what they said in their depositions and what they said in the courtroom provides added insights into just what happened on the night of the murders.

The first revelation about who was involved comes from Constable Rickerby. He deposed that after the initial investigations, on Lieutenant Hobby’s order, he took five men into custody for the offences. Those five he named as Edward Powell, Simon Freebody, James Metcalfe, William Timms and Thomas Sambourne. He had, however, taken eight men into custody. The additional three were John Pearson, William Butler and Bishop Thompson. The party making the journey to Parramatta also included Constable David Brown, Isabella Ramsay and Jonas Archer. David White gave his deposition the day after all the others so he probably travelled to Parramatta separately. One of the eight men arrested, John Pearson, had already promised, probably at Mary and Jonas Archer’s suggestion, to give prosecuting evidence against the others. When the depositions were taken before Magistrate Richard Atkins, Thomas Sambourne also decided to turn king’s evidence. Atkins fixed upon a final five that should answer charges and he named them in the ‘bond’. They were as per Rickerby’s deposition list of five except that William Butler’s name replaced that of Sambourne. Five was the number of people Atkins listed, knowing he had two of the eight men in custody promising to give king’s evidence. When the trial opened Rickerby named the men he believed guilty and this time the list aligned with those who had been charged. In other words Rickerby changed his evidence. How the eighth man, Bishop Thompson, avoided being charged is not clear. Although his deposition gives no useful information, he was listed in the bond as a potential witness to appear before the court. However, he was never called. He was certainly lucky because John Pearson had named him as being amongst the people who escorted the three Aborigines out of Isabella Ramsay’s house.

The Governor was in Parramatta for several days before the prisoners and witnesses arrived from the Hawkesbury. He claimed, in what he later wrote, that he was ‘made acquainted’ with the circumstances of the murders and that he sent someone to the site where the bodies were buried.2 In his letter to Portland he said it was ‘highly necessary to have the murderers taken immediately into custody, and a court was instantly ordered for their trial’.3 It is not hard to imagine that Governor Hunter may have ordered the arrests although there is no indication in the evidence given by Lieutenant Hobby and by Constable Rickerby that he gave the order. Six days elapsed between the murders and the taking of the majority of depositions. Hunter may indeed have been the man directing Lieutenant Hobby to make the arrests.

Hunter may also have influenced Magistrate Atkins and Constable Rickerby as to the number of men that should stand trial. However, this is pure supposition, given there is no other explanation for why Atkins listed only five to be charged and Rickerby told the court he had arrested five when he had actually arrested eight.

Isabella Ramsay told the court that a crowd of people took the three natives out of her house leaving her alone, presumably alone with her children. That crowd included the eight men arrested by Rickerby and perhaps others. Witnesses for the prosecution—Thomas Sambourne and John Pearson—were amongst the crowd, as was the lucky Bishop Thompson. Witnesses did not name any others as being present when the two boys were killed. However, Sarah Hodgkinson, widow of the murdered Thomas Hodgkinson, may also have been there. Alternatively, she could have been nearby at Powell’s house, waiting to be escorted home. She almost certainly had been at Isabella Ramsay’s house earlier that evening, with Simon Freebody, in order to question the three Aborigines.

The two men who turned king’s evidence, Pearson and Sambourne, gave unreliable testimonies to the court. They both failed to name those who murdered the two boys although Pearson said those who took the three Aborigines outside were the five defendants plus Thompson. All five of the defendants claimed they were not present when the boys were killed. One person only told the court who killed Jemmy and Little George. It was David White, the settler living five farms further down the reach from where the murders took place. He was not present at the murder scene but Richard Dore allowed his hearsay evidence. He said that on the evening the natives were killed, Timms and Freebody returned with Sarah Hodgkinson to her house where he, White, was waiting. He asked them what had happened. Simon Freebody told him that Butler had been holding one native who struggled free and ran away, with Powell firing a musket shot after him. Freebody said he killed another of the natives himself, using a cutlass. The third native was held by Timms and shot by Metcalfe. White’s story of what they had told him was the same in court as it was in his deposition. His words were different but the meaning was the same. In their defence statement Timms, Freebody and Butler said that White had come forward as a witness out of ‘hatred and malice’ against Powell, who had several times had to search White’s property for stolen goods. But White’s testimony was just as damaging to them as it was to Powell. When they told David White what had happened that night—and there is little reason to doubt they did tell him—they obviously had no idea there could be repercussions. In all probability David White’s testimony is the closest we get to the truth of what happened. Eight or more people were involved in taking the three Aborigines outside, probably to hang them. Powell, Timms, Freebody, Butler and Metcalfe were directly involved in the struggle that ensued some fifteen minutes after Isabella Ramsay closed her door. Perhaps that struggle happened as the hanging rope was thrown up and over the limb of a tree. One Aborigine got away and the other two were murdered on the spot. White’s deposition had not led to the five men being charged—Magistrate Atkins had already named them when White gave his deposition—but his testimony could certainly have influenced the jurors to believe they had the right men in the dock.

Isabella Ramsay, like James Metcalfe, had omitted Sarah Hodgkinson from their stories about the actions that occurred that evening. However, it was Sarah Hodgkinson who wanted the three Aborigines killed in retribution for her husband’s death. With two toddlers and a newborn to care for, she had the sympathy of the Argyle Reach community. And so Isabella Ramsay and James Metcalfe decided, perhaps the morning after the murders, to protect her from any repercussions by excluding her in their accounts of who had been present in the house. However, when Edward Powell was faced with justifying the murders he did say that it was done at Sarah Hodgkinson’s request. Sarah herself admitted her role to Constable Rickerby when he asked her the question directly. But she was never called to the court to answer for the part she played. It seems she also had the sympathy of everyone involved in the investigation.a

Who Killed Hodgkinson and Wimbo?

The historical record is inconsistent as to who were the killers of Hodgkinson and Wimbo. Jonas Archer said that Yellowgowie had told him Major White and others killed Hodgkinson and Wimbo. Archer’s labourer John Pearson told the court that the three natives in Isabella Ramsay’s house had said it was Terribandy, Major White and others. However, Metcalfe and Ramsay themselves never got further than hearing the boys say they had slept in the two men’s camp the night before they were killed and that two others had done the killing. Nobody else in Isabella Ramsay’s house that evening said they heard the natives name the killers. John Pearson’s version may well have come second-hand from his employer, Jonas Archer.

On 15 July 1804 the Sydney Gazette reported

Major White and Nabbin, the two natives lately killed at Richmond Hill, were the two identical persons who between four and five years since inhumanly and treacherously murdered Hodgkinson and Wimbo, the gamekeeper and settler on the second ridge of the Mountains, wither they had unfortunately straggled in search of the Kangaroo.

Richard Dore’s Competence

The question of Richard Dore’s competence as a Judge-Advocate is something that emerges from this saga. From a review of the cases that were referred back to London, some comment on Dore’s leadership in the criminal court is warranted. On the matter of all those split decisions, perhaps if Dore had given better guidance there would not have been so many. When it came to serving in the criminal court the antipathy between the officers of the Royal Navy and the New South Wales Corps became obvious. It was probably an historic navy–army antipathy aggravated by the fact that a naval officer held the commander-in-chief post in the colony. The army had the numbers but the navy held the command. That dynamic at play in the courtroom could provide an excuse for Richard Dore’s apparent inability to bring the jurymen to agreement. Nevertheless it is evident that, when there was disagreement, Richard Dore consistently aligned himself with the army view.

Richard Dore seems to have not understood the rule about hearsay evidence. He allowed hearsay evidence in the Isaac Nicholls case, the Chapman Morris case, and in this case of the Hawkesbury five. Whether he did not understand the rule or just chose to ignore it, we cannot be sure. He was a trained law officer but without previous experience as a barrister or judge. Governor Hunter understood when hearsay evidence had been admitted so it makes no sense that Richard Dore did not also understand.

Dore was determined to oppose Governor Hunter’s wishes on a number of fronts. Hunter soon began documenting his problems with the Judge-Advocate and the letters between them show how trust and respect for each other evaporated. Thereafter Dore sided with the Governor’s opponents. He was happy to go along with John Macarthur and other officers of the New South Wales Corps in their campaign to undermine the Governor’s authority. John Hunter’s disappointment in his Judge-Advocate was well founded.

Hunter’s Interpretation of his Instructions

When Governor Hunter refused to punish Aboriginal Charley it was a decision that did not sit easily with the New South Wales Corps. Corporal Farrell’s testimony about what the Governor said when he brought in Charley might have been exaggerated. Nevertheless it does seem to represent Hunter’s idea about how the Aborigines were best punished. Farrell had reported the Governor not wanting to punish Charley because he thought it was too late to make him understand what offence he had committed. The punishment had to be immediate, or as close to immediate as possible. Hunter was not afraid to give orders for the punishment of Aborigines. He had, two years earlier for example, ordered the New South Wales Corps to hang a native in chains from a tree if they detected him robbing a settler. He knew that would frighten the Aborigines, and it would be immediate punishment.

Hunter must have had the same principle in mind when he came across Pemulwy near Botany Bay in April 1797. He did not attempt to recapture him and Pemulwy was relieved at the news the Governor was no longer angry. If he was no longer angry then Pemulwy no longer feared any retribution from him. But Pemulwy did not become a friend through this generous act of forgiveness. He continued in his campaign to dissuade settlers from remaining on their farms. Similarly, Charley continued to cause problems for the settlers in the Hawkesbury area. It seems that Hunter was giving the message: if we don’t catch you soon after you create a problem for us, then time will make us forgive and forget. It is understandable why the New South Wales Corps and the settlers might have thought that bad policy.

Perhaps Hunter had been influenced by Governor Phillip’s attitude when he was wounded in the shoulder by an Aborigine’s spear. Phillip did not seek to punish his attacker because, as Collins reported, ‘as he could not punish him on the spot, he gave up all thought of doing it in the future’.4 Hunter thought Phillip exemplary in his handling of the Aborigines and perhaps adopted the idea never to punish unless it was immediately following the attack. But Phillip’s attitude to his own attacker was based on a need to conciliate the whole tribal group who had witnessed the attack. The attack on Phillip happened because of a misunderstanding, a misreading of Phillip’s intention. Punishing the Aborigines would have been counter to Phillip’s aims at the time of befriending the whole tribe.

‘Captain John Hunter.’ Engraving from a paintinh by R. Dighton. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

Governor Phillip had also punished a group of convicts who tried to avenge an Aboriginal attack on one of their mates. In March 1789 a large body of convicts from the brick-making gang set out to punish the Aborigines who they believed had killed one of their gang. The man had been collecting a particular plant used by the men for making a sweet tea. Sixteen convicts set out, with stakes for weapons, to find the offending natives. They ended by facing around fifty Aborigines near Botany Bay. Six convicts were wounded and one killed. Phillip had the men punished for two reasons: for disobeying his order to remain in the safety of the settlement, and also for trying to revenge themselves on the natives.5

By 1799 the settlement was widespread and settlers were far flung from the protection of town or village. Perhaps John Hunter believed that by limiting acts of white retribution upon the Aborigines to immediately after an attack or a theft, that he was instituting a control measure. It would reduce bad treatment that some white people had dealt the natives—wanton acts of physical abuse sometimes extending to murder. Up to that point the only redress had been through the Aborigines’ own payback. Hunter believed the bad treatment, and the payback attacks, had to stop. He would make people understand by bringing to trial those colonists who mistreated Aboriginal people.

That the Aborigines were subjects of His Majesty and thus under the protection of His Majesty’s government was a fanciful ideal that had no practical meaning to those in the colony. But that high-minded notion had been incorporated into the instructions of all the early governors of New South Wales. Perhaps it satisfied those in the British government who saw themselves as having a responsibility to turn humane ideals into government action. This instruction remained unchanged for decades and continued to challenge successive governors of New South Wales. It was an ideal without any thought or guidance as to how it could be implemented when amity and kindness failed to keep the peace. In modern parlance it was a policy without an implementation plan.

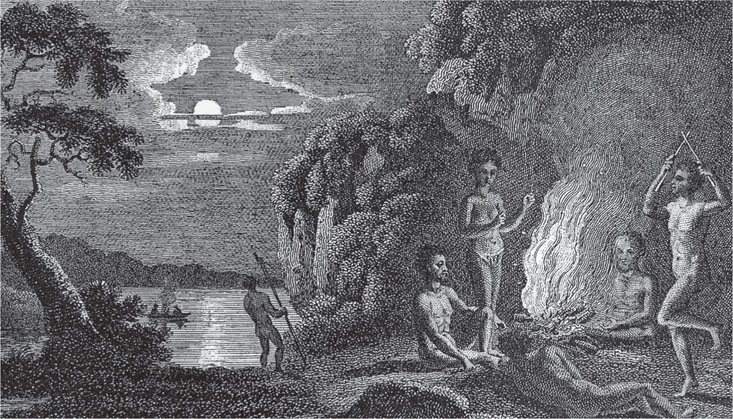

This drawing of a group of Aborigines gathered around a campfire was published at the beginning of Volume 2 of David Collins’ An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales. The text above the picture, probably written by John Hunter, reads: ‘It were to be wished, that they never had been seen in any other state than that which the subjoined view of them presents, in the happy and peaceful exercise of their freedom and amusements.’

It is interesting that it is Hunter who draws a conclusion during his own governorship that Phillip may have got it wrong—it may have been wiser to keep the natives at a distance, and in fear. Hunter believed that familiarity with the white people had brought on the evils the Aborigines suffered. If they had been kept away from the settlements, he then may have been able to deal with them without so much severity.6 It was an admission of defeat.

Hunter’s government and general order of 22 February 1796 had called upon settlers to come to each other’s aid when attacked by the natives. They were to keep the natives at a distance and discourage them from lurking about the farms. However, wantonly killing them was forbidden and could end in a charge of murder. If we assume Hunter’s order became widely known amongst the settlers one wonders if it may have led to some confusion as to how they could act. Fear of the Aborigines could well have played a pivotal role when trouble arose. A settler afraid of the local tribe might well have considered firing a musket at an approaching group of armed Aborigines. He was discouraging them from being on his farm. How far should he let them approach before he fired? Would his firing the gun be a wanton act? Or could he claim he was provoked?

It is clear from the trial evidence that many settlers had friendly relations with the local tribesmen. If Hunter’s government and general order of May 1796 meant that the settlers should change their approach to the local Aborigines—discourage them from entering the farms—then it failed on that score. People such as Jonas Archer, John Tarlington and Thomas Hodgkinson continued to try and keep a good relationship with the local clansmen. What might have been the challenges for a settler who changed his stance with the Aborigines—telling them he could not longer be friendly and accept their visits— telling them they were no longer welcome?

‘The different views & landscapes which appear from the banks of this river are extrem’ly beautiful and wou’d much amuse a good painter.’ John Hunter to Joseph Banks, 20 August 1796. Papers of Sir Joseph Banks at the State Library of New South Wales, Series 38.03, p.3. This view of the Hawkesbury River is from the sketchbook of John Andrew Bonar, who went to Australia in 1857. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

Although Hunter’s order did not specify how defensive actions should be carried out it is clear that retaliation, both before and after Hunter took over as governor, was officially condoned and sometimes directly ordered. Parties of soldiers had pursued Aborigines and indiscriminately killed them. Settlers were sometimes incorporated into a punitive party or they initiated their own hunt for the offenders. Given that attacks from the Aborigines were frequently by surprise and retaliation was not immediately possible, the question of distinguishing between retaliation and a wanton act of killing would be potentially difficult. It seems the only person in the colony who was particularly interested in making this distinction was the Governor. As successive governors were charged with the responsibility of seeing that the Aborigines were protected, the issue would continue to plague them for decades. The way the policy operated, it was a farce. Governor Hunter’s own words to Portland (2 January 1800) give an indication of the challenge inherent in a policy of sanctioned retaliation. Hunter was reporting the murder of the two native boys at the Hawkesbury River saying that it had happened

notwithstanding Orders have upon this subject been repeatedly given pointing out in what instances only they were warranted in punishing with such severity.

Legitimacy of the Defence

The five men found guilty of wantonly killing two Aborigines undoubtedly believed the charge was unjust. Jemmy and Little George, despite their youth, were Aborigines who had attacked and killed white settlers in the past. They had murdered Nicholas Redman and also attacked and wounded others. Thomas Hodgkinson and John Wimbo were also, possibly, their victims. Sarah Hodgkinson thought it more than possible. The execution of these two lads by the Argyle Reach settlers was, they believed, deserved. Yes, the killing had been deliberate but they believed it was within the bounds of current orders and government policy, although Lieutenant Hobby maintained otherwise. Hobby had ordered those on the burial party to kill any Aborigines on the way out or the way back. The time frame is not clear, but Jemmy and Little George were killed very soon after the party returned, perhaps a day or two at the most. Although nobody admitted to firing the musket or wielding the cutlass, they understood the killing was a deliberate act of retribution, and it was justified— Jemmy and Little George had earned their fate.

Ex-sergeant Goodall asked how should he act in future if Aborigines were to attack him again. But he knew that self-defence legitimized killing Aborigines. The unspoken question was this—were he to pursue the natives who attacked him, could he then be charged with a crime?

Had Powell, Metcalfe, Timms, Butler or Freebody been asked the question directly they would have conceded that the two boys were not in an act of provocation at the time. On that point the naval officers were agreed—the absence of provocation at the time made the killing a wanton act of murder. Had the charge been murder they certainly would have been found guilty on that basis. Jemmy and Little George were not in an act of provocation at the time—the only defence that could have excused murder.

How did the colonists view these events? A search for any evidence of popular reaction to the trial has revealed almost nothing. People like Goodall were confused about how they should act in future. That the five men found guilty of killing Jemmy and Little George were released back to their farms would seem to have wiped away the potential public impact of the guilty verdict. The letter of one convict who arrived in Sydney in July 1799 reveals a view that may have been shared by other people at the time. Since the trial was in October that year, William Noah was amongst the colony’s populace when the verdict was brought in and the prisoners released. He wrote notes on various aspects of life in the colony. We know the foundations of the new gaol were laid late in 1799 and the building was nearing completion when Noah wrote his rather lengthy description of what it was like to live in New South Wales.7 Regarding the law and how it worked he wrote the following:

If guilt of Thieving or Forgery or Criminal Offences you have a Hearing. If it is against you Commitd to Prison for a Criminal Court Orderd by the Judge where he sat as in England. The Jury being Composd of the Heads of Army and Navy. here is no Counsil nor Lawyers to Rob you & If your Case Comes to a Point of Law the criminal is respited & the Case sent to be Desided at Home by the Judges.8

William Noah thought that the court’s inability to finalize a case was over ‘a point of law’. It seems both Governor Hunter and the officers of the New South Wales Corps were successful in the one matter they agreed upon—playing down their differences to the public.

However, some people in the colony did recognize the behaviour of officers in the criminal court for what it was. In one of his early letters back to London Governor King recommended some changes to the criminal court’s jury composition. He suggested that if some of the civil officers—there were then six civil officers in the colony—were also called upon for jury duty it would address the complaints of colonists that the military officers were not always impartial in their judgments.9

a Sarah Hodgkinson’s plight received some attention from Governor Hunter. He must have agreed to a plan to improve her situation as he granted her 60 acres of land closer to Sydney town, at Petersham Hill. (Reference: HRA, Series 1, Vol. 2, p. 463). Nevertheless she kept an interest in the Hawkesbury farm as part of it was later sold under her son Thomas’ name to Sarah’s second husband, Thomas Upton. (Reference: Registers of assignments and other legal instruments, Book 9, page 4, entry 6, 11 September 1822)