«You cannot solve a problem with the same kind of thinking that you used to create it» (Einstein).

In many countries there has been a veritable explosion of diagnoses of ADHD, alias Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, probably for a number of reasons: socio-cultural, political, economic, personal and psychological. These days, society as a whole offers a pace of life that is too rapid for the biological rhythms of the body and mind, creating false idols and false objectives to pursue, with a lack of valid models with which to identify. There is often induction by contagion and imitation through TV images, movies and commercials, whose characters display personal aspirations beyond the realistic reach of young viewers. All this creates distress and unhappiness, and given the structural weakness of the individual, their evolving sense and discernment is unable to resist manipulation and standardization.

Thus, the multinational drug companies insinuate themselves into families suggesting “chemical straitjackets” for their “troublemakers”, promising happiness and serenity with a pill for every ill: Prozac®, the happy pill, Ritalin®, the serenity pill, Strattera®, the balance pill, and so on. Every problem has a pill to reach “psychic heaven”: who can resist such rapid and apparently effective solutions?

Who doesn’t have problems at the family, personal and psychological level? In single-parent families, or “blended” families with children from previous relationships, how do we combine a career, homemaking, children, partner, parents and time to relax? And if the children get sick, what do we do? Where do we find the time to listen to them and take care of them?

And here comes the diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder to relieve us of all our responsibilities, from the feeling of being inadequate, of living in a superficial and heedless manner. In fact, the more diagnoses there are, the more the disease is constructed: the more parents or teachers diagnose it. After all, there are questionnaires and anyone can administer them, and evaluate them as well! Perhaps, in the frenzy to diagnose ADHD, there is no longer any need for doctors...

As we were writing this chapter, we read an article by Moritz Nestor2 in Current Concerns3 citing the German weekly Der Spiegel no. 6 of February 2012:4

«The American psychiatrist Leon Eisenberg, born in 1922, “scientific father of ADHD”, gave his last interview at the age of 87, seven months before his death, in which he said that “ADHD is a prime example of a fictitious disease”».

In the same article we also read that, «the Swiss National Advisory Commission for Biomedical Ethics (NEK) issued a highly critical judgment on the use of Ritalin®, a drug used to treat ADHD, which states that consumption of pharmacological agents has altered the behaviour of children without any contribution from them, thus interfering with their freedom and their rights. Pharmacological agents in fact induce behavioural changes, but they are not capable of teaching children how to make these changes on their own. The children are thus deprived of the essential learning experience of how to act autonomously and empathically, which limits considerably their freedom and alters the development of their personality».5

Today we know that the brain relies on a number of factors if it is to function correctly. These influence its anatomical development and its psycho-physiological structure. These factors are worth remembering, as they are the basis of both affective-emotional balance and mental and physical health, as well as distress and illness.

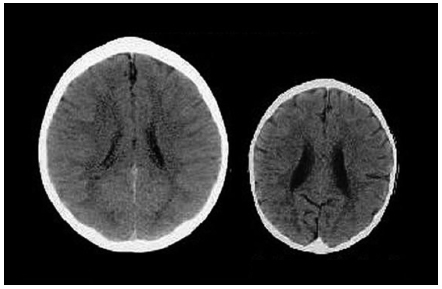

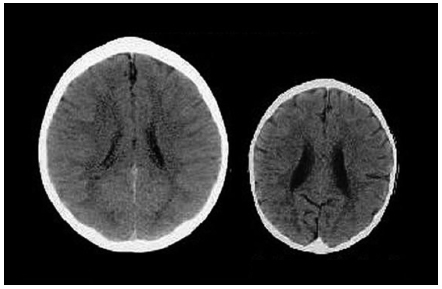

The brain on the left is that of a normal 3-year-old child, well cared for by his mother, and is significantly larger and with less dark areas than that on the right, belonging to a three-year-old who has been seriously neglected by his mother (Photo Bruce D. Perry, MD, Ph.D. / Child Trauma Academy).

Is there an alternative to the “chemical straitjacket” to help children manage their excesses and difficulties? In fact there are several. And they all begin with education or the enrichment of the training of the adults with whom the children interact.

The problem is that adult society, which should serve as a model, does NOT know how to handle its own excesses and problems, and responds to the intemperance of the child with equally intemperate reactions. We stop at the superficial level of the child’s behaviour because we have not developed enough empathy to feel what suffering is being manifested by such actions. This attitude is actually rooted in a widespread delay in accepting the paradigm shift that has been required in every branch of human knowledge since classical physics, based on solids, was replaced by quantum physics.

We have been accustomed for centuries to imagining a reality that is pre-existent to the observer, described in three-dimensional terms and believed in absolutely, in which each object is material, located in space and separated from the rest by its borders. Since the time of Descartes we have deduced being from thinking (cogito ergo sum – I think therefore I am), and we believe that there is a whole composed of parts, which therefore can always be analysed, categorized, disassembled and reassembled like the pieces of a machine. This separative vision, which excludes the interactions between the whole and each phenomenon, has had time to infiltrate into every field of knowledge, and in particular those regarding the body, made up of cells and atoms, solid and circumscribed, where illness, including mental illness, is seen as damage or “a broken machine”. As Gioacchino Pagliaro10 explains, in order to be accepted as a “science”, still defined according to the old paradigm, psychology too developed the tendency to look for trauma in a mind that is not working and to consider the mind and mental states as mechanistically dependent on the structures of the brain and nervous system. Such and such a disorder must be matched to such and such a cause in a linear fashion, and linked to this specific fragment of history. Even the psychosomatic refers to this causal and mechanistic model: if on the one hand it accepts that mind and body affect each other, sometimes widening the vision to the society in which the person is immersed, on the other it completely forgets that everything that surrounds us and permeates us, and of which we are a part, influences us and informs us, and we ourselves, in our turn, influence it and inform it.

Then quantum physics arrived and gave us a wake-up call: every apparent part of the Whole is both part and the Whole: is both individual and quantum field, the drop is both the drop and the ocean. The observer influences what he or she observes, and to the vision of separate objects placed in time and space is added spatial and temporal non-localization.

Information – both what I receive and what I produce – is not only related to the types of communication that we know: we are part of a field of infinite, non-directional energy that knows everything about itself at all times – many scientists are beginning to talk of a “field of quantum information” – and oriental contemplative disciplines lead us into non-ordinary states of consciousness from which the immense field of energy-information becomes consciously accessible.11

However, if consciousness is still considered from the perspective of the culture of linearity and the conception of one subject inexorably separate from the rest, how long will it take for this new vision to inspire parents, carers, therapists or teachers in the difficult task of combining and articulating instinctive emotions, rationality, spirituality, theory and practice in an harmonious way in their everyday tasks? How many know how consciousness and personality are formed, the importance of the environment for growth, and how vast is the network of information and influence of which consciousness is a part, whether we are aware of it or not? How should we deal with the great problem of transmitting this knowledge? What new dynamics underlie and influence the difficult art of becoming a “new” parent, carer or therapists or teacher? We barely know how interactions between physical development and individual consciousness, between personal rules and collective values, between changes in the natural environment and changes in the cultural environment promote changes in society’s “economies”, customs, culture and ideas. How this can be implemented correctly and rendered feasible on the level of everyday individual behaviour is still a matter of debate and research. Yet it is certain, according to the new paradigm, that we are the constantly changing product of all this, and much more.

It is now well known that the cause-and-effect model of linear causality, which until the 1950s underlay any research method, must necessarily be integrated with that of circular causality, a theoretical model that must underlie research and construct practise. Perhaps it is time to reverse course if – as claimed by Prigogine12 – the path of European culture has been schizophrenogenic. It must now be time to reflect on a way to integrate knowledge and coordinate learning.

Thus, therapeutic coordination and integrated therapy go hand in hand: there cannot be one without the other as the therapeutic element is integration itself, and that is what enhances the healing process. And here by healing we mean the ability to use lost functions and the possibility of developing talents possessed but as yet unexpressed.

Clinical and therapeutic experience tells us that most of the discomfort and psychological suffering of educators and therapists is inherent to their subjective interpretation of the child’s behaviour, conditioned by individual experiences that sometimes do not allow them to see the child’s real and natural needs or desires.

How do we find a fresh vision unaffected by past conditioning that is able to accommodate the new?

An unusual inspiration is appearing in our culture, one that takes its cue from the other end of life.

Here, the combination of one of the greatest thanatologies on the planet, the Tibetan, and more advanced studies in neuroscience has produced the empathic care of suffering, particularly that which occurs at the end of existence, which, however, has many points in common with the suffering that goes with ADHD: the dying and the child are both, for a number of reasons, eminently empathic, and the people who care about them are extremely involved in their suffering.

This extraordinary body of studies on death and dying – perhaps the most comprehensive in the world describes the mental state that dominates the end of life with unparalleled thoroughness, highlighting the quality of empathy. It is a quite different state from that which our minds are usually in when we are still in the midst of life, as it is different from the one we experience when we are dreaming.

The carer relies on this empathic quality, entering into a state of great calm and great compassion through special meditative techniques, which is then felt by the dying person by virtue of the empathy inherent to the final phase of life. “Absorbing” a state of great peace and compassion is the best guarantee of a good death, one that is not disturbed by regret, guilt, fear, matters left unspoken or unresolved. The mind can hold only one thought at a time, and if it is at peace, the rest is automatically excluded.

This form of end of life care supports the dying as well as those who love them, and even the therapists involved. It requires that you cultivate a state of empathic listening, by which we perceive the needs of others even when they can no longer express themselves in the conventional way, i.e., by talking. It is interesting to reflect on the fact that a restless or obsessive child also suffers a discomfort he cannot verbalize: the same technique of empathic listening is therefore useful here, to perceive the child’s real needs and avoid projecting onto his suffering what we “believe” could be helpful instead of what the child really wants. On p. 49 we will tell the story of Vincenzo: he knows what he needs but no one listens to him, no one lets him speak.

The person carrying out the meditative techniques of “compassion” is therefore the carer, and the recipient of the state of calm, the cared for.

In the case of our “differently active” children, the person carrying out the meditative technique is above all the adult who “cares for” and “listens to” the restless child, who absorbs the state of peace.

The empathy aroused in the carer is strongly present naturally in every one of us: it is not a quality that is acquired only at the end of life, although at that stage it becomes more acute, but is instead a characteristic of human nature itself. Or rather, not only of humans, because mirror neurons – the next topic, which is discussed on p. 25 – have been identified in some species of birds and monkeys, and we can assume that further investigation will discover their presence in all those species that rely on the empathic cohesion of the group for their very survival.

If we are born with it, empathy must be present in children (see Lipton’s studies on the brainwaves prevalent in children according to age, cited on p. 104).

And it is this that gave rise to the idea of applying the techniques of care and empathic listening for the dying from Tibetan thanatology to the suffering of ADHD children.

Empathic listening today could be better defined as “empathic and compassionate” listening, and we shall soon see what is meant by “compassion” in the great Tibetan tradition to which we will often refer.

The reason for this redefinition lies in the most recent discoveries of Tania Singer, head of the ReSource Project conducted by the Max Planck Institute13 in Leipzig, Germany, confirming that the area of the brain that is activated in states of empathy is not the same as that which becomes active when you feel compassion, that is, when you wish that someone were free from suffering. Empathy alone, Singer rightly claims, is dangerous: the area of empathy is developed even in the brains of psychopaths. A torturer, for example, must know exactly how much his victims are suffering in order to inflict more suffering on them. On the other hand, what is not developed in him is the area of compassion. So when in this book we talk for brevity’s sake of “empathy”, our reader should realize that, given the goals we have set, we refer not to pure empathy, but ethically-oriented empathy, that is, guided by compassion.

Empathy is a way to know the other where we can feel what he or she feels while remaining distinct from him or her: distinct, but not distant.

The term compassion here should be understood in the sense of the contemplative tradition to which we refer, and is very different from pity, which maintains a distance between the one that feels strong, and the other, perceived as weak. It is rather the healthy desire to relieve the suffering of the other, while taking care of ourselves at the same time. The XIV Dalai Lama often defines compassion as “the inability to tolerate another’s suffering”, and Sogyal Rinpoche14 describes it in these terms:

«Compassion is a far greater and nobler thing than pity. Pity has its roots in fear, and a sense of arrogance and condescension, sometimes even a smug feeling of “I’m glad it’s not me”. As Stephen Levine says: “When your fear touches someone’s pain, it becomes pity; when your love touches someone’s pain, it becomes compassion”. To train in compassion, then, is to know all beings are the same and suffer in similar ways, to honour all those who suffer, and to know you are neither separate from nor superior to anyone».

This leads us to an empathy aimed at the common good of the two people in a relationship. While Spencer may have convinced us that the law of the survival of the fittest could justify social disparities and permeate evolution, we should remember that Darwin emphasized the combination of cooperation and competition – and not only competition – as the reason for human survival under difficult conditions. Empathic abilities are partly innate and partly cultivated, as demonstrated by a famous experiment: an educator eats with a small child, both equipped with a spoon. The educator breaks his spoon, and the child before the age of one tries to imitate him, while the child who is more than one year old comes to the rescue of the adult lending him his spoon. The Theory of Mind reminds us that at around four and a half years of age a representation of what is in the mind of the other appears in the child’s mind; and we know that after the age of seven empathy can be inhibited in humans but not in animals: in another famous experiment, bonobos stop pulling the cord that allows them to get food as soon as they realize that every time they pull, bonobos in another cage receive an electric shock.

Compassion, says Paul Gilbert,15 goes in three directions: from me to the other, from the other to me, and from me to me. And there are meditative practices for all three cases.

Empathy is a form of knowledge that leaves the door open to information that travels in a different way from that which we are accustomed in the old paradigm. In the quantum field to which everything belongs information is transmitted through a vacuum, without friction and instantly. There is no time interval between the moment when the information “leaves” and when it “arrives”.

Physicists have struggled to understand this, because it seemed that information was propagated at a speed greater than that of light. Eventually they realized that the speed was not only greater: it did not exist. It was not necessary. In the quantum field everything seems to be in contact with everything, always, so communication does not need to “occur” at a higher or lower speed, it is always present, and thus instantaneous. We can say that in the quantum field time does not exist, because time is not necessary to move within it.

This means, among other things, that to be conscious at the level of the quantum field would be equivalent to be in instant communication with everyone and everything, in fact with all the information contained in the universe, at all levels.

This extraordinary vision has now opened the door to new investigations into empathy, and further confirmation has come from neuroscience and neurocardiology.

We now know, thanks to the discoveries of Giacomo Rizzolatti, that we are all equipped with mirror neurons,16 so called because they allow us to reproduce the pain or joy of others as if they were our own. They seize from the other not the act but the intent, which is why cognition occurs not only through theoretical learning but also through direct experience, the latter being a process of immediate understanding, not imitation.

The suffering of others or their joy always becomes “mine”, even at the unconscious level. The classic example is the tightrope walker on a wire: he teeters and I, the viewer, “teeter with him”. I feel as if I am falling, even if I am sitting in the audience.

And the more empathic I am – such as the child or the dying – the more I absorb the emotional state of those around me.

Tibetan thanatology explains that the dying person becomes increasingly empathic as the senses, carriers of other processable information, gradually “turn themselves off”,17 and this makes him fragile, as a child is fragile, because of his high degree of permeability.

However, this permeability can be used to a good end in a conscious and aware way. The therapist, like the carer of the dying, can attain and deliberately maintain – thanks to meditative techniques – a state of great strength and peace, which can be felt by the other person. If we are serene, the dying (or the child) will also become serene, just as they will become tense or anxious when we are.

Perhaps we remember the principle of synchronization of oscillatory systems through resonance that we studied in high school: it is not quantum physics, only classical physics.

One example is the phenomenon of the pendulum clock, invented by Christiaan Huygens in the XVII century. Huygens was very proud of his collection of pendulum clocks. One day he noticed that all the pendulums swayed together in the same way. Intrigued, he changed their positions so that the oscillation of the pendulums was independent, but some time later he was astonished to observe that the pendulums were again swinging together in the same way. Since then, the phenomenon has been extensively studied, and we know that it covers all oscillatory systems, both living and mechanical. It is thus stated: “In an oscillatory system, the phenomenon of synchronous drag means that the element that oscillates the most drags the one that oscillates less powerfully”.

One of the most important consequences, which is always valid, is that in every oscillatory system, both material and biological, maximum efficiency – the maximum performance for the least energy expenditure – is achieved when all parts are synchronous, in perfect harmony.

When the heart, main oscillator of the human body, is able to impose its rhythm, all other oscillatory systems of the body, at all levels – physical, emotional and mental – are automatically harmonized by the main rhythm. All their specific functions are thus optimized.

So far, it is not evident what this has to do with empathy, is it? But it will soon become clear.

It happens that in the presence of another oscillatory system (the heart of another person, in other words) the most powerful system – rendered powerful by being harmonious and aware, in our case – tends to drag the other, in accordance with the principle stated above. The organism of the other therefore experiences the consequences.

The bioelectricity produced by the heart is from 40 to 60 times greater than that produced by the brain and the heart’s electromagnetic field is 5000 times higher than the brain’s. In fact it is more potent than all the other organs’ electromagnetic fields. Its electrical energy not only pervades every cell of the physical body, but it interacts with that of the brain – an interaction that has allowed researchers to explain the complex effect of cardiac brain waves in greater detail.

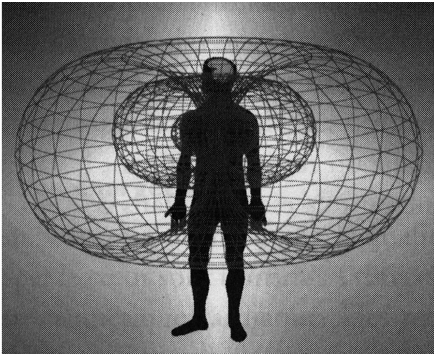

The appearance of this electromagnetic field, which in its optimal state has the shape of a perfect torus18 (see following figure), reacts to emotional states. When we are troubled – fear, anxiety, stress, frustration, etc. – it becomes chaotic and unorganized. In scientific terms this is called an “incoherent” or “inharmonious” spectrum. When one feels positive emotions such as gratitude, compassion and forgiveness, it takes on a much neater appearance, the so-called “coherent” or “harmonious” spectrum.

The electromagnetic field of the heart extends around the body up to a distance of 2-4 meters,19 therefore the information contained in heart energy is received by all the people around us.

The electromagnetic field of the heart. © HeartMath Institute.

The interesting thing is that the heart is also at the same time a brain: it contains an independent nervous system of a different material to the grey matter, and is composed of over 40,000 neurons, to which is added a dense and complex network of neurotransmitters, proteins and support cells.

Thanks to these refined circuits, the heart seems to be able to act by itself, to make decisions and take action independently of the brain. It seems to be able to learn, remember, and even perceive. 20

Your heart might therefore have a role in intelligence and the perception of reality, but what role? And what kind of intelligence resides in the heart? Language does not lie when it invents expressions that exist throughout the world, pointing to the heart as the seat of feelings (“he has a good heart”, “she is hard-hearted”, “it breaks my heart”, etc.). And in the Tibetan tradition, in which meditation training in compassion follows protocols that are strikingly similar to the therapeutic visualizations to activate the brain of the heart promoted by the HeartMath Institute, “compassion” is called nyinjé, which translates literally as “the heart that opens up”.

The neurobiologist Michael Gershon21 reminds us that we have yet another brain, the gastrointestinal nervous system, with an independent network of 100 million nerve cells located in the oesophagus, stomach, small intestine and colon, with similar biochemical reactions to those of the brain. These two brains were found to be interconnected and interacting, although the gastrointestinal brain is able to act independently, learn, remember, and is in turn neuroplastic, i.e. may change and grow, etc. It produces the famous sensations defined, not by chance, as “visceral” which in ways not yet fully explained certainly capture information present in the internal and external environment, producing well-being or discomfort. Again, we note that in all languages there are metaphors that evoke the activity of the gastrointestinal brain: “having a gut instinct”, “my guts tell me”, “I can’t stomach him”, “I feel it in my gut”.

Expressions such as “get under somebody’s skin” or “this person makes my skin crawl” can be found in many languages. This would lead us to believe that other parts of the body are able to receive information that is not necessarily related to their sensory function: the skin, for example, is linked to touch, but we have “skin-related impressions” independent from touching. Developments of the research of Italian neurologist Giuseppe Calligaris, active until 1944, are interesting in this area. His work has now been taken up by two other Italian scholars, Gandini and Fumagalli,22 who have developed a form of therapy that passes from so-called “skin patches” to “energy network”. The skin is the largest organ of the body, and transmits personal and external memories, a sort of two-way radio equipment.

Transmitting the state reached by the carer to the person being cared for is linked to the fact that both have access to the same state of consciousness, from which perceptions change drastically. We will try to describe this perceptual change.

Thus, we are “empathic animals” by nature, and we now know that the dying person, the child and the carer who cultivates his own empathy with special techniques share a privileged form of communication.

Because in our society they are not cultivated, since we prefer to orientate education to the development of logical-rational abilities, considering, wrongly, that they are more necessary for survival in our competitive society.

It is useful here to make a brief foray into the analysis of the mind that forms the central axis of Buddhist philosophy and psychology, which has also been well received by the greatest neuroscientists of our time.

Buddhism holds that all phenomena, including the mind, come with an appearance and a true nature. In this case, the recent discoveries of quantum physics seem to support the Tibetan position, the result of an empirical approach over thousands of years, since today it tells us that we are part of a single endless wave, which is by definition unlimited, has no direction, is all-pervading, capable of giving and receiving information (i.e. it is cognitive, as shown by Gisin’s experiment at CERN in Geneva in 1998),23 and the source of every phenomenal manifestation.

Every apparently localized phenomenon is nothing but the temporary result of an array of forces that make it manifest to our eyes and our instruments; while its true nature is, in fact, a wave. Phenomena, including the body, are therefore to the wave as the mind is to the cognition of the wave, so that the true nature of minds and bodies of each type is that of an infinite field of intelligent energy, which in itself contains all possibilities and from which everything arises moment by moment, continuously changing, and obviously transcending time and space.

If, therefore, this kind of infinite cognition is the true nature of our mind, it must also be good as well as wise, since there is no wisdom in wishing evil of something that is a part of oneself.

However, the true nature of the mind, good and wise as it is, is not often seen in operation in this world of ours. Why? Because it is obscured by the appearances of the mind, by the inevitable – given their conditioned nature – productions of its dynamism. The mind cannot help but produce thoughts and emotions, most of which are quite turbulent and cause suffering. The problem, however, is not the production of the mind, but the fact that, due to a perceptual distortion, we convince ourselves that that is what we are, we identify with the production of the mind rather than its (our) true nature, a bit like a butcher identifying with his sausages... He would spend his life in fear of being eaten!

We label this very mobile gathering of thoughts, emotions, body, memories and habits “I”, identifying ourselves with something highly unreliable: this continuously changing mind, and this body, whose cells are constantly being renewed (in the time it took you to read this page you have lost more than 104 million!).24

To quote His Holiness the Dalai Lama, «The I is nothing but a mere designation». We are the ones who give it a solidity that it does not possess, and it ends up obscuring our true nature, the extraordinary non-separate awareness, which underlies the appearance or production of the mind (thoughts and emotions).

The process of distancing or distracting us from our true nature is fortunately reversible. As Sogyal Rinpoche says, «You do not need to become enlightened. Just stop being prey to illusion». Meditation techniques allow us to experience our true nature once again and, with training, to dwell in it. Here there is no separation, empathy reigns supreme, an ethical empathy, because the nature of mind is good, as we have seen.

In short, this true nature of ours is always present, even when it seems lost: it is only temporarily obscured by the perceptual distortion of separateness that usually taints our relationships with others, with external phenomena, and with ourselves, a distortion that makes each individual perceive themselves as a separate entity from the rest of the real world and from other individuals, leading us to favour dualistic relations (subject-object).

If these dualistic relationships are based on positive emotions, such as the desire to care for others, they can have positive results, such as the assistance that is offered to the sick by many associations or in hospitals, but nevertheless they are partly affected by the illusory view of separation and not based on the perspective of union, confirmed by quantum physics.

Einstein understood this very well. Despite being a fervent supporter of particle physics, he was ahead of his time when he wrote:

«A human being is part of a whole, called by us the “Universe”, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separated from the rest – a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circles of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty».25

The empathic care of suffering inspired by the Tibetan tradition starts from here: if that is our true nature, there must be a state from which it is possible to communicate with the other, transcending the separation of subject and object. The first translations into Western languages of this approach spoke of “spiritual care” to define this dimension, which is attainable but not ordinary, and is described in the different spiritual traditions all over the planet. Later the word “contemplative” began to be used, but a more precise term used today might be “empathic care”, where “care” already contains within itself the profound ethical value of this empathy.

Beyond discussions on terminology, the interesting thing is that the last decade has seen the beginning of a vast neuro-scientific and anthropological enquiry into the techniques that these traditions have developed to achieve this brilliantly intuited state. In particular, the early years of the XXI century are seeing top-level research into meditative techniques that derive largely from the corpus of Tibetan Buddhism, which reveals a particularly interesting field of study and practice, partly because it has emerged so recently from the isolation of its Himalayan enclave that it is still absolutely intact.

To try to describe the first person perception of the state we are looking for, we can say that if in the ordinary state the famous cogito ergo sum (“I think therefore I am”) prevails, which infers being from thinking, the consequentiality between the two acts is reversed in the empathic states achieved through meditative training: sum ergo cogito, “I am, therefore I think”. In the first case, we identify ourselves with our thoughts and our emotions, which are very changeable and, above all, as confirmed by the flat encephalogram, die with the body. In the second case another state is revealed experientially, which transcends thoughts and emotions and in which one can dwell stably, if only one can learn to achieve it and ignore distractions. An expert meditator is not even distracted when he relates to others by means of thought, word or gesture. It is, of course, a desirable condition in a delicate context such as that of caring for any kind of suffering, where you are constantly faced with critical situations that would otherwise elicit highly emotional states.

We wish to emphasize once again that removing the barrier between subject and object does not give rise to a state of fusion, but allows one to share with the person cared for a state in which the latter will not only be less tormented by the fear of death or other disturbing emotions, but from which he can find that he can think, speak and act. The task of empathic care is therefore to empathically restore to the other this state of profound wisdom and great compassion, in which both the terminally ill and the ADHD child, both by definition the epitome of helplessness, can sometimes find that they are more powerful than they have ever been before.

For example, the terminally ill find that in the absence of quantity of life they can have access to an unusual quality of life, a fullness that sometimes they themselves define as extraordinary, which sustains them in moments of physical pain, when they feel sad or frightened, and which grants a wider vision, where these negative feelings are no longer dominant.

Disturbed children discover that there is a state that transcends the emotions and thoughts to which they are usually attached, which continuously distract them, reducing their attention and ability to concentrate: they begin to see them as products of their minds to which they can choose not to be attached, not to adhere to, just as, after the so-called “anal phase”, they no longer feel attachment to their own poo.

This state, which initially can be achieved only for a few seconds, becomes stable with training, and it has to do with the neuroplasticity26 of the brain. It has been shown that it activates the areas that govern the ability to act, wellbeing and compassion, etc.; and this happens at the expense of other areas responsible for stress generating destructive emotions – and, in the case of the amygdala27, also capable of weakening the immune system.28 It also brings about neuroendocrine changes, stimulating important enzymes, such as telomerase, which slows down cell aging (see p. 141).

To understand how meditation can help us face the most turbulent emotions, it is enough to think that it can apply even at the moment of death. Dying while meditating is an aim of the Buddhist and Hindu traditions, because what matters is how we are when we live and how we are when we die. There have been people who received empathic care at the end of life and passed away in perfect serenity, even if they died of lung cancer: their eyes did not show a fear of suffocating but the ability to quietly control their last breath. There was a persecuted person who understood at the end of life that his persecutors were themselves prey to particularly stubborn perceptual distortions, who no longer called them “bad” or “executioners”, but simply “ignorant”. Compassion gives the victim a power that is total, extraordinary, full of dignity, magnificent. At the end, this person even overcame the trauma of the Holocaust that he had carried with him all his life. There have been women who have suffered violence, who from the empathic state have been able to overturn their own scale of values: from judging their own rapists in terms of good/bad, they passed to perceiving them as people who are a long way from discovering their own natures. These women therefore have been able, at the end of their lives, to replace fear and hatred with compassion. “Now I am strong”, said one of them who was raped, but who came to terms at the end of her life with this experience she had never verbalized before.

From the meditative state it is therefore even possible to relive part of one’s own history in a different and liberating way, a reinterpretation of reality29 that is not negligible at the end of life, when all the knots and unfinished business of our past come home to roost, but also not negligible at a younger age, where emotions swing between the feeling of omnipotence, often guilt-inducing, and the sense of helplessness. We will describe how this was decisive for a child with ADHD, who we have named Julian, on p. 75.

Thus, dispelling many Western misconceptions, both the Tibetan corpus and scientific experiments show us how meditative states are not just private moments, mystical and silent, but measurable mental states that can be achieved through study and training, from which we can continue to think, speak, act and interact, although animated by a totally different vision of things from what we experience in our “normal” state. We have already mentioned how in a relationship with someone who is aggressive, for example, one can discover a vision of things that is not conflictual because it is non-dualistic, and thus will not cause stress. The usefulness of this state for children in distress is self-evident, as it is for those who deal with them, as is also the case with the terminally ill.

To give an idea of the changes that studies on meditative states have brought about in the dogmas of science, and also in behavioural studies, it is enough to think that the myth of the “startle response” that science considered uncontrollable, has collapsed. This is the cascade of movements of five muscles around the eye that contract in the presence of a sudden or very sharp noise or movement. It has now been demonstrated that a well-trained meditator does not perceive even a sudden sound, as powerful as a gunshot near the ear, as threatening, so that the involuntary blink does not occur.

Physicists working on the basic structures of matter have found that solid matter is made up mainly of empty space. It follows, as has been said, that anyone who uses scientific reductionism to analyse physical matter will not find any solid particle as the basis of the structure of any object that we perceive as solid. What we perceive as solid material is in fact an assembly of infinite and minute energy potential vibrating at different frequencies, called “strings”.

It is important to understand the term “potential”. The revolutionary discovery made in 1927 by physicist Werner Heisenberg was called the “uncertainty principle” because it postulates that the nature of what will be observed has only a potential form before the observation takes place. In other words, the observations and measurements conducted by researchers affect what is being observed.

What has this got to do with children with ADHD?

When researchers set their equipment to find subatomic particles, they will find particles; when the equipment is set to find electrical charges, they will find electrical charges. Researchers find what they are inclined to find. Al Siebert,30 one of the leading experts on resiliency,31 wrote:

«Psychologists and psychiatrists have not studied how their expectations influenced the person or people being studied. When [...] they looked for symptoms of mental illness, emotional trauma, or impairment, they found illness, trauma, and impairment.

Mainstream psychologists are only recently beginning to discover that when they look with positive expectations for good coping skills, resiliency, and post-traumatic growth, they find what they look for. It’s been in people all the time, but reports of such abilities were dismissed as anecdotal stories because the abilities could not be replicated in scientifically controlled settings. Resiliency-psychology research is opening psychologists to seeing a new, validating way of viewing how humans respond to adversity. Resiliency research is revealing the existence of a way of being human that cannot be understood by traditional, scientific, reductionistic methods».

In light of the above, the debate around whether ADHD, which affects many of our children by making them intolerably restless, is or is not a disease does not necessarily fall within the scope of this book, which simply takes note of the fact that the suffering associated with this kind of disorder exists and is considerable, and tries to suggest a new approach, derived, as we have seen, from the empathic care of terminal illness, which is great enough to epitomise all other suffering.

The suffering that arises from ADHD does not involve only the child, just as the terminal phase of a person’s life does not involve only the person who is dying. As John Donne would say, “no man is an island”, and all our emotions affect those around us who care for us, for better or worse.

The innovation of the approach presented in this book is threefold:

In fact there is nothing new under the sun, and as early as 1948 the research work of Bertalanffy33 and subsequent studies throughout the world have clearly shown the mutual influence between individuals and between individuals and the environment, leading to the general theory of systems, where each individual is a system, contained in several other larger systems, within others larger still. In short, everything is interdependent, interacting and intercommunicating. By changing an element of the whole, the outcome itself changes, such as when you change a number in an addition of even a thousand numbers: the result will never be the same. A butterfly fluttering its wings disturbs a star, as quantum physicists say today, paraphrasing an old Native American saying; if an individual changes, so does the entire system that contains it.

If we, as parents, educators or therapists and carers change, the child will also change.

2 <www.currentconcerns.ch/index.php?id=1608>.

3 International Swiss online publication dedicated to independent thinking, ethical questions, the promotion of international laws for respect of the public and human rights <www.currentconcerns.ch>. See also <http://www.current-concerns.ch/index.php?id=1608>.

4 Jörg Blech, “Schwermut ohne Scham”, in Der Spiegel, no. 6/6.2.12, pp. 122-131.

5 Human enhancement by means of pharmacological agents, Opinion no. 18/2011, Bern, October 2011. <goo.gl/4bSMOL>.

6 Bruce D. Perry, M.D., Ph.D./Child Trauma Academy.

7 The article about this study was published in the Medical Daily and is available in English at: <goo.gl/RkrdiI>.

8 “Circadian” derives from the Latin circa diem and means “around the day”. It is an endogenous rhythm that manifests itself roughly every 24 hours, but is capable of adapting to a number of external signals, the most common being daylight. “Ultradian” rhythms refer to cycles or phases that are repeated within the 24 hour period, like the dilation of the nostrils or the arrival of the appetite, or those of the cyclical 90-120 minute phases studied by those researching sleep patterns.

9 Physicist and philosopher, Ernst Mach (1838-1916) was also a neuroscientist ante litteram.

10 Italian psychologist and psychotherapist, for many years professor of Clinical Psychology at the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Padua, director of the UOC of Clinical Psychology at that AUSL in Bologna and founder of both the Italian Society of Psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology and the International Association for Research into Entanglement in Medicine and Psychology (AIREMP). His publications include: Mente, meditazione e benessere, Tecniche Nuove, Milano 2004 and, with E. Martino, La mente non localizzata. La visione olistica e il Modello Mente-Corpo in psicologia e medicina, UPSEL Domeneghini Editore, Padova 2010.

11 See Alan Wallace and Brian Hodel, Embracing Mind, Shambhala Publications, Boston 2008.

12 Ilya Prigogine (1947-2003), Russian chemist and physicist noted for his theory of complex systems.

13 The ReSource Project, where ReSource means to “return to our source” but also “to develop one’s skills”, is a longitudinal study of Eastern and Western methods of training the mind. The project is still underway as this book goes to press. The head of the research is Tania Singer, director of the department of Social Neuroscience at the Max Planck Institute. For eleven months, 200 participants have been engaged in a wide range of mental exercises that aim to improve attention span, self-awareness, mental and physical health, the healthy regulation of emotions, caring for oneself, compassion, empathy and perspective. The main purpose of the training is to improve participants’ mental health and social skills, reducing stress and promoting lucidity and the level of individual satisfaction, as well as leading to a deeper understanding of the point of view, values and actions of others.

The project obviously has no religious connotations, and has been developed by a team of scientists, psychotherapists and expert teachers of meditation. You can follow the developments on the website <http://www.resource-project.org>, in English and German. At a congress at the Mind and Life Institute in January 2013 on “Mind, brain and matter”, Tania Singer announced the new discoveries in research still in progress. A recording of the entire meeting, which lasted for several days, is available on Yahoo in English under the heading “Mind and Life XXVI: Mind, Brain and Matter”: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l4xRgIhTGeo&index=6&list=PLOafJ4rP1PHwafTGL23zXK29kn-JsXMbMg>.

14 Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Harper Collins, New York 1992, 10th Anniversary Edition, p. 204.

15 Paul Gilbert is the head of the Mental Health Research Unit of Derby University in the UK, where he teaches Clinical Psychology. He has spent the last two decades developing CFT (Compassion Focused Therapy), which recently became particularly interesting with the development throughout the world of Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness approach, increasingly used to treat mental problems such as depression, stress and stress-related insomnia. Recently, along with the Buddhist expert Choden, he has published Mindful Compassion, Robinson, London 2013, in which he combines practices of training in Mindfulness and those related to training in compassion.

16 Matteo Rizzato and Davide Donelli, I Am Your Mirror. Mirror Neurons and Empathy, Blossoming Books 2014.

17 See Sogyal Rinpoche, op. cit.

18 «In mathematics, a toroid is a doughnut-shaped object, such as an O-ring. It is a ring form of a solenoid. Its annular shape is generated by revolving a plane geometrical figure about an axis external to that figure which is parallel to the plane of the figure and does not intersect the figure. When a rectangle is rotated around an axis parallel to one of its edges, then a hollow cylinder (resembling a piece of straight pipe) is produced. If the revolved figure is a circle, then the surface of such an object is known as a torus» (Wikipedia).

19 The measurements of the HeartMath Institute refer to a distance of 2 meters, but the Tibetan tradition does not suggest any such limit. While Westerners try to sit in the last row when attending a course with a meditation master in order to be able to exit without disturbing anyone, Tibetans try to occupy the first row, aware that the closer you are to someone who reaches a certain meditative state – in this case, the teacher– the more you can take advantage of the “oscillator effect”, and enter the same state as the trainer (although of course the tradition does not use the same terms from neurocardiology and physics).

20 To find out more, visit the HeartMath site: <goo.gl/ISiW4W>. On the same subject: Silvia di Luzio, Start With The Heart, BlossomingBooks 2014; various studies, including that by HeartMath, can be found in “Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine”, July/August 2010, vol. 16, no. 4.

21 Michael Gershon The Second Brain, HarperCollins, New York 1998

22 Samantha Fumagalli and Flavio Gandini, Dermoreflexology. How To Talk With Our Unconscious Through Our Skin, BlossomingBooks 2014.

23 At CERN in Geneva at the end of the 1990s, the physicist Nicolas Gisin continued Aspect’s work and demonstrated that two objects, even if separated by many miles, can form a single entity. This opened up new avenues of research. He was able to prove that two photons sent along optical fibres in opposite directions, 18 km apart, move in harmony, simultaneously making the same choice. What did the information travel on? Certainly not on the light, which travelled only a few centimetres in the time in which the information between the two photons covered the 18 km that separated them.

Gisin had no alternative but to confirm Aspect’s hypothesis, i.e. that the photons shared a common fundamental reality, a wave of energy (and as such it is unlimited and present everywhere simultaneously). We do not know if he dared to add that the wave must also possess a cognitive nature, cognition being summarized as giving and receiving information.

24 Between 50 and 100 billion cells die in a human being every day. Taking the average as 75 billion, 104,166,666 cells have been lost in the two minutes that it would usually take to read a page!

25 Albert Einstein, Ideas and Opinions, Crown Publishers, New York 1954.

26 A concept recently introduced in neuroscience, which indicates the ability of the brain to change its structure in response to a variety of intrinsic or extrinsic factors i.e. thinking, learning and life experiences, which also affects the genetic heritage.

27 The amygdala (Latin, corpus amygdaloideum) is an almond-shape set of neurons located deep in the brain’s medial temporal lobe.

28 Britta K. Hölzel, James Carmody, C. Karleyton Evans, Elizabeth A. Hoge, Jeffery A. Dusek, Morgan Lucas, Roger K. Pitman, and Sara W. Lazar, Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala, 2009, available online at <goo.gl/z7Gkbi>.

Italian studies on the impact of meditation on stress and the immune system are still rare. Early research includes two pilot studies on staff at Parma Hospital, awarded the Premio Terzani for the Humanization of Medicine: Daniela Muggia, Accompagnamento empatico fondato sulla tradizione tibetana in contesto ospedaliero: due studi, 2008. Published online at <goo.gl/OZssi3>.

29 Outcomes of the Shamatha Project include a longitudinal study in which many of the most eminent neuroscientists of our day are still involved. A test on facial expressions measured the reinterpretation of reality by 30 participants trained in meditation for three months (with six hours of meditation and two hours of discussion per day) and 30 people in the control group. The facial expressions of the participants were filmed while watching interviews of soldiers returning from Iraq, and researchers examined all the frames one by one in search of Ekman’s famous “microexpressions”. It turned out that expressions of sadness were equally frequent before and after the meditation retreat, while those of anger, contempt, disgust, initially as frequent as those of sadness, were radically reduced. The attention of the scientists then shifted to the latter, and the participants were subjected to another test. The researchers gave them a story to read and a list of definitions of emotions, and asked them to write down, as they read, which of these emotions they experienced. Their facial expressions were filmed and compared with the definitions they wrote, and it emerged that even the sadness was not the same thing as before: the facial expression was actually sad, but this term was used differently. It meant “sympathy” and “suffering” rather than the emotion of sadness itself. It thus became clear that in a trained mind the facial expression of sadness had different connotations, empathic concern for the fate of the other, which is the basis of compassion in the Buddhist sense of the term.

30 Al Siebert, The Resiliency Advantage, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco 2005.

31 “Resiliency”, from the Latin resilire, “to spring back”, “rebound”, is a term that psychology has borrowed from technology, where it defines a material’s power or ability to return to the original form, position, etc., after being bent, compressed, or stretched. In computing, where the use of this term is even closer to the way it is used in the field of psychology, it is often associated with disaster recovery, i.e. the ability of a system to adapt to changing conditions of use, making it able to dispense the services it would perform in normal circumstances. In the case of man, it indicates the ability to deal with crisis situations, to recover readily from illness, depression, adversity, and the like, and to come out even stronger than before.

32 Mandala is a Sanskrit term that can be roughly translated as “wheel”. It represents the universe so as to highlight the interdependence of all its parts and the dynamic equilibrium that results from this. It has a centre and a circumference, often inscribed in a square with four “doors of entry”. The psychologist David Fontana interprets its symbolic nature as an aid to «access progressively deeper levels of the unconscious, ultimately assisting the meditator to experience a mystical sense of oneness with the ultimate unity from which the cosmos in all its manifold forms arises». Jung, on the other hand, saw the mandala as a representation of the unconscious self, using it to identify both emotional disturbances and the path to regaining the Totality.

33 Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901-1972) was an Austrian biologist, as well as the founder of general systems theory. He joined the Circle of Vienna and in 1945 published his major work, General Systems Theory, predicting the change of paradigm that we are finally discussing today. He wrote among other things: «The basic change I would venture, first, is the replacement of the image of man as robot by that of active personality system [...] that is, a dynamic order of parts and processes. Mental dysfunction is a system disturbance rather than a loss or disturbance of single functions [...]. The robotization in modern society actively suppresses spontaneity or creativity; no wonder that either neurosis or socially unacceptable behaviour – tantrums, drug addiction, vandalism, and crime as an outlet – is the result». Quoted in: W. Gray, F. J. Duhl, N. D. Rizzo (ed.), General Systems Theory and Psychiatry, Little, Brown & Company, Boston 1969. This quote has been retranslated from the Italian version of this book.