One

First Bites

I was born on the eve of war and Holocaust on August 1, 1941, at Harper Hospital in Detroit. By family legend, I began eating immediately and with prophetic zest. The exact content of that first meal is unrecorded, but I am sure it didn’t come directly from Mom. She, like other advanced women of her time, believed that science offered a nutritionally superior and more hygienic way to feed her baby than she could herself.

I was born on the eve of war and Holocaust on August 1, 1941, at Harper Hospital in Detroit. By family legend, I began eating immediately and with prophetic zest. The exact content of that first meal is unrecorded, but I am sure it didn’t come directly from Mom. She, like other advanced women of her time, believed that science offered a nutritionally superior and more hygienic way to feed her baby than she could herself.

Powdered “formula,” dissolved in water and delivered in sterilized bottles with rubber nipples, replaced the mammalian teat in millions of American households of that era. Of course, many mothers today still choose to trade the intimate mess and exposure of nursing for the technoid ritual of preparing and delivering formula to their infants: mixing, washing and sterilizing bottles, flicking the heated “milk” on their wrists to check that it isn’t too hot, remembering not to tilt the bottle too high for fear of drowning the child as he feeds, hunting for a new formula when Beloved Nipper refuses the one you started him out with.

I was not that balky kid. I never refused a bottle. Far from it. Not long after we returned home to our bastard Tudor house in the comfy Russell Woods neighborhood, I was sucking down three bottles at a feeding. At a year old, I weighed thirty pounds, and Geneva, the jovial black nanny, couldn’t force my galoshes over my chubby ankles.

Did this gorging cause the allergies that afflicted me as a toddler? Childhood asthma, sensitivity to eggs, sulfa drugs, feathers, dust—they all vanished once I began eating solid food in saner amounts. By the time I turned four, my weight had become normal for my age and height, but who can say if, fourteen years later, some molecular ghost of those bottled banquets lurking in my blood didn’t touch off the nearly fatal reaction I suffered from a wasp sting at an outdoor mixer at Brandeis University in the late summer of 1959. A wasp at Brandeis.

Tempting as it is to blame Mother for that (and so much else), the lusty appetite was all mine, a spontaneous urge as normal to me as a cry or a burp. She merely enabled it. Looking back on my writing career, I can’t help thinking that I was born hungry and unusually interested in what I put in my mouth. Nonetheless, my family life stood behind that natural inclination.

When my paternal grandfather, Barney Sokolov, arrived in Philadelphia around 1910 from Kremenchug, a dreary industrial hub on the banks of the Dnieper in what is now Ukraine, he enrolled in an engineering program at Temple University, hoping to leave behind the life he’d known as a farmhand and the training he’d had as a bookbinder in Europe. But marriage and fatherhood came quickly. My father was born in 1912. Then news of a better life in the American West led Barney away from a technical career in Philadelphia and back to the land.

Already in 1911, another immigrant Jew, Benjamin Lipschitz, who called himself Ben Brown, had begun leading some 130 other Yiddish-speaking, socialist immigrants to the state of Utah, where they formed a Zionist agricultural commune on Homestead Act land outside the barren town of Gunnison. The Clarion Colony never overcame the triple jinx of poor soil, insufficient water and undercapitalization.* But in our family, it was remembered as a heroic adventure. Baby carriages were threatened by coyotes. Even hardy shtetl products like my grandmother were unprepared for the comfortless life, despite the cordial welcome and advice they got from Mormon neighbors.

I was also unprepared for the bleakness of Gunnison, when I managed to piggyback it onto a working trip for Travel + Leisure magazine. I drove through town on a great-circle tour of the mountain time zone in the 1970s, that paradisiacal era when you could get off a flight at some midpoint and continue on later, for the same fare as an uninterrupted transcontinental nonstop. As a freelance writer, I maximized my work possibilities and my private travel interests by cannibalizing a Travel + Leisure ticket to California, issued to me as part of an assignment for an article on fish restaurants around the country, into two segments with a stopover in Salt Lake City. I paid local rates for a Hertz car, which I then drove south through Gunnison to Death Valley, continuing on to Mount Whitney, Reno, Pyramid Lake (Nevada) and back to Salt Lake for the flight to San Francisco. Along the way, I climbed Mount Whitney and baked a cake at the summit for a Natural History column on high-altitude baking (the batter boiled in my camper’s oven but did subside into an edible cake, which I, too nauseated from soroche, fed to an astonished hiker, who later nominated me, unsuccessfully, for a Guinness title as world’s highest baker) and did research for my biography of A. J. Liebling, Wayward Reporter, at Pyramid Lake, where Liebling had reported on the evils of aerial hunting of wild mustangs. I also spent a lurid, sleepless night at an isolated motel on a lonely stretch of Interstate 80 east of Winnemucca, kept awake by the angry shouts and then the ecstatic squeals of the couple in the next room.

My stop in Gunnison, Utah, had not been much pleasanter. The small town’s principal landmark was a prison. As I ate a toasted cheese sandwich at a lunch counter, next to a tobacco-chewing fellow in snakeskin boots, I tried to imagine my grandfather struggling to make a go of it there.

Little had changed from the bleakness the first arrivals had seen in 1911, as Goldberg noted:

As Ben Brown steered the wagon westward out of town, the colonists strained to see their land.… Although lacking in farm experience, Barney Silverman became concerned. The land sloped steeply, resembling the sides of a “large saucer.” The “raw earth,” as Isaac Friedlander described it, was bare of trees and covered with sagebrush, shadscale, and tall, thin grasses. Large patches of ground were devoid of any vegetation.… The site of the base camp was a particularly dubious place to begin cultivation. Yet, this determination was out of the Jews’ control. The stage of canal construction had dictated the initial area of farming in the southern part of the colony on some of the worst land in the tract. Silverman also noticed that no well had been dug for water.

After five wretched winters, Clarion went under. Ben Brown stayed in Utah and prospered in the wholesale egg distribution business, the capitalist opposite of everything he and the Clarion Colony had once stood for. My hapless family, now including my uncle Eugene Victor Debs Sokolov, born in Utah in 1913, the year after the socialist E. V. Debs ran for president for the fourth time, decamped to that Kremenchug in Michigan, Detroit, where we had a wealthy second cousin.

Her welcome was a hollow one. She died soon of diabetes, leaving Grandpa Barney to improvise a living on the margins of the Detroit food economy. By the time I got to know him, in the early 1950s, he was operating an old-fashioned fish market—smoked whitefish, herring in barrels—on Michigan Avenue not far from the city’s skid row. At one point, he had banged together coops in his backyard, raised chickens and sold them to neighbors during a butchers’ strike. Even after he had his own shop, he kept his hand in as an agriculturalist with a little home vegetable garden that brought him his only worldly fame. In 1950, the gardening page of the Detroit News extolled the pumpkin he’d coaxed to grow up a post. When my sister and I were taken to Grandpa’s house on our weekly Sunday visit, I ran eagerly out to the garden to see this wondrous climbing cucurbit. It was very small and wrinkled.

The fish market was equally uninspiring. And it came to a tragicomic end. Grandma Mary inherited the building and, guided by my father, rented it out, first as a doctor’s office, then as a bookstore. Or so everybody thought. Yes, the tenants did sell books, but naughty ones, and there were girls upstairs. Police eventually raided the place, and Grandma Mary, a sheltered homebody, barely Anglophone, was cited for running a cathouse.

She, too, built a life around food, chopping carp for gefilte fish, preserving Kirby pickles with copious amounts of garlic and dill in Mason jars. We would carry home bushel baskets of them every fall, and kept them in the rec room, slightly embarrassed in our half-assimilated way, by this mark of jener Welt, the old country no one ever mentioned.

Although my father’s first language had been Yiddish, which he relearned in after-school classes, the world of his grandparents meant little more to Daddy than it did to me. He did, however, join a Jewish congregation (very reformed) just before I was born, and volunteered for the Public Health Service after Pearl Harbor (the army turned him down because of a transient heart condition) to take a stand as a Jew against Hitler. And who would argue that for a young doctor to interrupt his career in order to teach other military doctors how to treat venereal disease with the revolutionary new wonder drug penicillin was not a selfless and effective contribution to the war effort? He and my miserable mother spent three nomadic years in a catch-as-catch-can life around army bases, fearful they’d be snubbed in allegedly anti-Semitic officers’ clubs, and actually were snubbed by locals in South Carolina and Texas who had had their fill of strangers on their way to war theaters in Europe and the Pacific.

In our family mythology, these were hard times, a descent into lumpenproletarian scarcity. Mother never stopped wincing over the unpasteurized Grade D milk she had seen on supermarket shelves in El Paso, home to Fort Bliss, or retelling the horror story of the Chicano boy who tried to get me to go shoot rabbits. I was three by then, and I had heard the noise of revelry by night on V-E Day in Columbia, South Carolina, not long after my neurasthenic mother had blithely chopped off the head of a chicken she’d been raising in the yard. As I watched it run around spattering blood on the bare dirt, I had no way of appreciating the spectacle as a reenactment of Grandpa Barney’s poultry caper in Detroit twenty years before.

What did I think about that chicken, my first exposure to meat production? I wish I could say that this barnyard violence troubled my soul ever after and fattened the wallets of therapists. Not so; nor have I shrunk from offing rabbits and geese when the necessity presented itself.

Mother did not continue her career as a home butcher after we left Columbia. But she did bring back one exotic culinary habit from the war. Chili.

The same Mexicans who terrified her with their low-class Thumper bagging and unpasteurized milk also fed themselves with delicious Mexican food that she and Daddy learned to love.

How did my timorous parents, who were tenderfoots par excellence, unable even to find the Chinese laundry at Fort Bliss, end up adopting a lip-stinging Rio Grande chili as their signature family dish? No, they did not attend the annual Original Terlingua International Championship Chili Cookoff in a Texas ghost town. Instead, my parents learned about Mexican food because of gonorrhea. The leading nightclub operator in Juárez, the lively town across the border, via the bridge over the Rio Grande, heard that a doctor at Fort Bliss had a miracle drug that could cure his case of the clap. He called for an appointment, and Daddy explained that the drug was in short supply and he couldn’t treat him. Even U.S. civilians couldn’t normally get it, only military personnel and their “contacts.” So unless this Mexican had had sex with a WAC, or perhaps a GI, and could prove it, Daddy wasn’t authorized to treat him.

Horacio Gutiérrez, as I will call him, had not become the leading figure in the raffish nightlife scene of wartime Juárez by accepting refusals from low-level bureaucrats, even if they were captains in the U.S. Public Health Service. He made another phone call, this time to someone at Fort Bliss who outranked my dad, and ordered him to treat Señor Gutiérrez.

He did so quite happily and cured him. From then on, all three of us Sokolovs were personae gratissimae at Señor Gutiérrez’s club. All of Juárez was officially off-limits to U.S. servicemen, but my father’s rank was high enough to get him past the MPs at the border checkpoint. So we went often, and ate and drank on the house, developing a taste for the free food on offer in unrationed Mexico. I wore my tailor-made captain’s uniform and acquired a little serape and a tiny guitar, so that I could sit in with the Mexican “magicians” when they played “Cielito Lindo” and “Amapola.” It was also the beginning of my career as a student of ethnic food and as a restaurant-world insider.

My father would have shuddered at the thought that he was preparing me for a life as a gourmet. He had no respect for friends of his who cooked as a hobby or made a big fuss about fancy food. Without exactly calling a gastronomically avid friend of his a homosexual, he made it clear to me that the meal he’d just eaten at the man’s house gave him doubts about the state of his host’s masculinity. Certainly, the fellow was wasting his time on an unserious obsession.

But then my father, a hilarious comic when the mood came upon him, felt compelled to dismiss large areas of life as “unserious,” or “making no difference in the world.” His standards for seriousness were high and self-undermining. Although he was a first-rate and successful internist, he let me know from my earliest youth that he hated the practice of medicine, considered it drudgery. The intellectual quality of routine patient care was tediously low. And he retired at the first opportunity, at fifty-eight, after twin retinal detachments brought him financial independence through disability insurance. Certainly, he never gave me a word of encouragement to follow in his footsteps as a doctor. But then he never gave me a word of advice about anything important.

When I announced that I was going to major in classics at Harvard, he opined that classicists didn’t make anything happen. But that was as far as he went, never offering any real opposition to the plan or even mentioning the subject thereafter.

Similarly, when I came home senior year with the news that I was intending to marry a non-Jewish woman, his reaction was one of indifference. Mother insisted that I make a special trip to see our rabbi for the first time in eight years, to tell him I was intending to marry a Christian. Dr. Richard C. Hertz of Temple Beth El tried to talk me out of the marriage. I would regret standing apart from mainstream Jewish life, he said. His trump card was that he wouldn’t officiate at the ceremony.

I had the presence of mind to point out that no one had asked him.

My father never returned to that subject, either. It would have been hypocritical for him if he had, since his background and personal convictions were irreligious, despite his nominal membership at Beth El. We did not observe the Sabbath or keep a kosher home. Neither did either set of my grandparents, although Barney and Mary Sokolov had retained a bemused nostalgia for the Orthodox practices of their European childhoods. When I was five or six, we went to their house for the only Passover seder ever celebrated in a home by our family in Detroit.

It was conducted with complete fidelity to tradition. Adult men reclined at the table on pillows and washed their hands when the Haggadah commanded them to. An older cousin asked the four questions in Hebrew, English and Yiddish.

But on all other days except that one, Jewish dietary rules were ignored, even if traditional Jewish dishes from the shtetl found a place on the table. From this liberated platform, my father and his classy if unstable bride vaulted onward to consuming treyf, unambiguously nonkosher food like ham, with a suspiciously oedipal zest.

Lobster, as rebarbatively treyf as a ham, was the emblem of their marriage. They honeymooned in Maine, tootling up the coast from lobster pound to lobster pound in a new roadster that was their wedding gift from Grandpa Joe Saltzman. Back in Detroit, one of their favorite restaurants became Joe Muer’s, the giant seafood place on Gratiot, where lobster was always an option. But Daddy was in true lobster heaven when he took me and my sister to the Maine shore in the summer of 1959. We ate our way through one lobster pound after another, starting the meal with steamed clams and then ripping apart chicken lobsters at bare picnic tables outdoors, within a sniff of the Atlantic.

Daddy never tired of telling me how he loved this “animal” dining experience. That it might be not only a transgression against the civilized dining standards Mother maintained at home but also a thumb in the eye of kashruth did not seem to occur to him. He affected indifference to Judaism, but not toward his identity as a Jew.

On one of those rare occasions when he took me on an outing that didn’t end up at a sports arena, we ate at a dingy deli called Lieberman’s Blue Room. The light was actually bluish, from overhead fluorescent bulbs. And the dish I ordered also had a bluish tinge. The budding food critic foreshadowed his later forays into exotic comestibles by ordering lungen, a dispiriting bowl of spongy, stewed lungs.

I couldn’t eat them. I don’t think I could do it easily today, but there is no risk of a test, since lungs cannot be sold legally in the United States: abattoirs no longer inspect them for human consumption.

Lieberman’s, despite its dismal decor, was a vibrant part of the old Dexter-Davison Jewish neighborhood, with its Ashkenazic immigrant flavor. When that increasingly affluent community fled an encroaching black population and resettled a few miles to the northwest, the Yiddishkeit of Dexter-Davison did not survive the move. The delis that did make it to Livernois and Seven Mile Road were sleeker and kosher in “style” only. Darby’s and Boesky’s (the family that produced the Wall Street felon Ivan, who mysteriously changed the pronunciation of his surname from the Bo-es-kee we all grew up with as customers to Bow-skee; he went to jail and the Boesky restaurants are gone) laundered the sometimes funky menu of places like Lieberman’s. No more lungen, or eiter (udder) either.

Our family ate most of its out-of-the-home meals at a group of forgettable genteel places with refined and distorted versions of ethnic food, none of it decisively phonier than what you would have found back then in most second-rank American cities, but phonier and with a shakier claim on local tradition than famous places in New York, Chicago, San Francisco or New Orleans at the time.

When I was fifteen, I was happy to be fed overcooked pasta at Mario’s, or greasy French-fried frog’s legs at Fox & Hounds, the pseudo-British roadhouse in goyish suburban Bloomfield Hills. Years later these forays provided me with a baseline of well-meant culinary fraud against which to see how the real thing in France or Italy stood out as sharply different from the culinary dishes we ate on those Sunday nights out in the Motor City of the ’50s.

Detroit was a backwater, but it did have two unique places to eat, one raffishly elegant and nationally acclaimed. The other was an eccentric burger joint disguised as a railroad train. I never ate at either one of them until I was in high school, and never with my family.

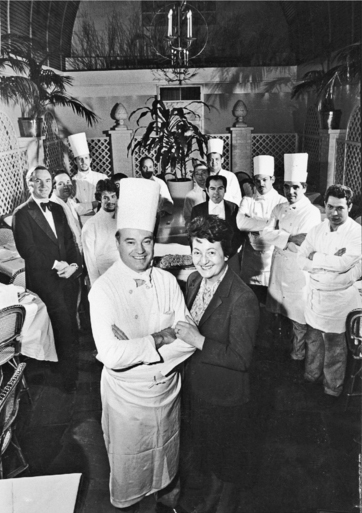

At the high end was the London Chop House, an eclectic downtown watering hole run by Les and Cleo Gruber, pals of James Beard’s (he named their glittery ‘21’ Club clone one of the ten best restaurants in the nation in 1961) and authors of an excellent guide to the restaurants of the world. The Chop House attracted Detroit’s big shots, car guys and real estate honchos, exactly the crowd my glitz-shy parents shunned. They would, however, consent to eat across the street at the Grubers’ less brash Caucus Club. Neither of the Gruber kitchens were temples of gastronomy. They didn’t offer much more than top raw materials—beef, lobsters, lake fish—plainly prepared and sold for top dollar. You’d get your name monogrammed on the matches at the table, but the food chef Pancho Vélez cooked for both places was full of shortcuts and off-the-shelf flavorants. According to the food-history blogger Jan Whitaker, Pancho did not hesitate to jazz up carrots with maple-flavored syrup or to stir onion powder into mashed potatoes.

At the other end of the culinary scale, a retired adman named Bill Brooks served unremarkable hamburgers on a dreary stretch of Woodward Avenue somewhere between the city limits and Birmingham to the north. But Brooks was a true snob, unlike Les Gruber, who would serve anybody who’d pay his freight. You couldn’t eat at Bill’s unless he approved of you.

First of all, you had to be plugged in enough to know that the locomotive-shaped building with no sign on it was a restaurant. Then you had to understand that the chef-owner, a gray-haired recessive, had a microphone concealed near the locked, bell-less front door. Initiates would stand there calling out their names and pleading to be admitted. If he agreed and felt like working that night, Bill would buzz you in to a dark and ill-kempt vestibule that led to a small semicircular counter. The proprietor would emerge from his little hidden kitchen, make a stab at a congenial greeting and take your order.

Before long, an electric train rolled out of an opening in the kitchen wall on the track that ran along the counter. Your burgers sat on little flat cars. Bill stopped the train several times so that the flat car with the appropriate burger came to rest right in front of the person who’d ordered it.

I knew that this food, and the rest of what we were getting in local restaurants, was mediocre stuff. I had, after all, been to Chicago many times—twice with my family and on several other occasions while changing trains on my way to Camp Kawaga, near Minocqua, Wisconsin. So I knew what you got in a really big city at legendary addresses (Barney’s, the stockyard steak house, and the slightly more sophisticated Fritzel’s, a showbiz magnet in the Loop famous for “continental” dishes like chicken Vesuvio and steak Diane), and at the nationally known Polynesian “gourmet” chain Don the Beachcomber. We even passed through New York City once on our way back from that Maine idyll. But my first glimpses of high-end food, more or less authentically prepared, were at home.

Mother was an excellent and ambitious cook. Her repertoire was built on the German Jewish kitchen of her prosperous childhood in Detroit. Anyone who has looked at The Settlement Cook Book knows what we ate. The author, Lizzie Black Kander (1858–1940), gave cooking classes in a settlement house in Milwaukee to young immigrant Jewish women from eastern Europe. Her goal was to help these greenhorns cope with America. So in her lessons she combined German and Jewish specialties such as Bundt cakes and matzoh balls with more “American” recipes like blueberry gingerbread and salmon loaf. There was also a section called “Household Rules,” a compendium of useful tips, such as how to maintain an icebox (a real one, with blocks of real ice; we had one like that ourselves at some point during World War II, stocked by an actual iceman, who cameth with large scary tongs).

Over the years and through many editions, Mrs. Kander actually increased the Jewish content of the book, perhaps sensing that much of her audience was, like my mother, already significantly assimilated and in need of grounding in the Jewish culinary heritage. Mother’s own repertory far exceeded the limitations set by Mrs. Kander. She would boast that she could cook dinner for a month without ever repeating a dish.

Since we were entirely unobservant at home, dietary rules played no part in what we ate. My father was the only one of us with any trace of the shtetl, and he was an unhesitating adventurer at table. So my mother had a free hand to broaden her horizons as a cook, a project she conducted with help from Gourmet magazine.

I never ventured into her kitchen, except after dinner to dry dishes on the maid’s night out. It was Mother who boiled the artichokes and deep-fried the eggplant slices, trimmed the sweetbreads and whisked together the hollandaise for the asparagus.

Wine did not appear in our house until I was in high school, a bottle of pinkish Almaden, which loitered half-drunk in the refrigerator for many days. You may take this as a vestige of Jewish tradition if you like. I was in college when my father told me he had just seen his first alcoholic Jewish patient.

Mother kept active in the kitchen well into her eighties, always picking up new recipes. (The spicy pecans of her invention coincided with the craze for Asian fusion in the 1980s world-at-large.)

When I left home for two years of boarding at Cranbrook School in Bloomfield Hills, a half-hour drive north of our last house inside the city of Detroit proper, I had been exposed, without realizing it, to a fairly broad spectrum of foods and food ideas, and I was inclined by my home training to opt for novel things to eat when they were on offer. Cranbrook, an architecturally magnificent complex built for a Detroit newspaper millionaire by the Finnish genius Eliel Saarinen, taught me many things—Latin poetry, English hymns, French-kissing—but it was an interruption of my alimentary education.

School food is school food is school food. I do, however, remember with affection a dessert we called anti-gravity pudding, because you could invert the dish and its contents would not fall onto the table. Cranbrook also taught me how to clear the entire service for a table of twelve on a single tray without dropping a glass or a saucer on the endless walk to the kitchen, past twenty-four tables of malicious teenage boys hoping you would lose control of your cargo. The trick was to load the tray on a sideboard so that most of the weight was piled on one side. Then you knelt beside it, slid the heavy side over your shoulder and stood up, very carefully. With practice, the tray could then be held with one hand, on the underweighted outer side, while the free hand swung smugly at one’s waist.

It is also true that I learned to appreciate rum before graduation, but I don’t count that as the beginning of real connoisseurship in the beverage department. Especially since my coindulger and I consumed the stuff with Coke and then got sick in a YMCA room far from school.

I didn’t learn much about food at Harvard, either. My college diet consisted of more school food punctuated with cheap eats at restaurants in Cambridge and Boston. To be fair, you could, and I did, try whale steak at Chez Dreyfus. Chez Jean on Shepard Street introduced me to rillettes and other traditional French bistro food. There was gussied-up New England fare at Locke-Ober. But like a whole generation of future American food lovers, I discovered the gastronomic me on $5 a day (and often less) bumming around Europe after freshman year, in the summer of 1960.

Armed with $1,000 from savings and gifts, I joined an unofficial student invasion of the Old World, which had still not entirely rebounded from two world wars and an intervening economic collapse. This meant that dollar-holding ephebes like me could afford to eat every night in charming Left Bank bistros like Julien et Petit or La Chaumière. And if you were actually me, an inchoate food obsessive smothered by thirteen years of anti-gastronomic formal schooling, you devoured not only the artichaut à la barigoule (including the fonds, which you saw French diners at nearby tables extracting from the leaves and broth) but the concept of an orderly food heritage—a cuisine. After a summer of assiduously feeding off menus written in a language as traditional as the Homeric Greek I’d just learned to read at Harvard, I had signed on, without consciously knowing it, to a lifetime of passionate interest in filling my mouth and brain with as much of this previously undreamed of culinary material as my late start and physical distance from the source would allow.

The strong dollar also bought cheap travel, first by air and then by rail, to every other corner of Europe my meager cognitive map of the continent suggested as a destination. The Eurail Pass was my carte blanche to Spain, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Italy and even Greece. In only thirteen weeks, I chugged through a kaleidoscope of European capitals and second cities, spending the days in museums and the evenings at restaurants that functioned as survey courses in European cooking.

On an early August evening, I boarded not the Orient Express but a by-blow named the Simplon-Orient Express, because it passed through the Simplon Tunnel from Switzerland to Italy and then continued on through Yugoslavia to Athens. After four dismal, sooty, hungry nights on the train, I was back in my element, imbibing the food of Greece—the plethora of mezes, the lamb in all forms and, outstandingly, the supernal melons in the garden at the Byzantine monastery of Hosios Loukas in Boeotia.

Later that summer came the raspberries in Venice and Florence and Rome, lamponi, served with cultured, vaguely sour, thick cream or with sugar, but never both, unless you asked nicely.

So by the end of that thirteen-week sojourn in Europe, I had seen the Mona Lisa and the caryatids at the Erechtheum, St. Paul’s Cathedral and the Rembrandts in Amsterdam. But what had been planned as a cultural “grand tour” on a student budget had turned into a voyage of gastronomic discovery, a self-taught survey course on the cuisines of Europe, with cultural landmarks crammed in between meals.

The most important research project came almost at the end of the “course.” I went to Maxim’s in Paris. It had three stars in Michelin, but an eighteen-year-old American with $20 could eat there as if he were King Farouk. I ordered caneton aux pêches, duckling with peaches, not oranges. The menu said the dish came right out of Escoffier. Now, I thought, I was in touch with the highest and best a person could experience, a variation on a great French dish by the greatest of chefs; classic. And like those other classic monuments of European culture, from Aeschylus to the mansarded roofs of the Louvre, this culinary monument, and all the hundreds of classic dishes I’d met with, were part of a tradition that had gelled for the ages.

And you could eat it. Again and again.

With cuisine, as with classical literature, you had a fixed text, or at least an archetypal recipe to which all those dishes I was eating arguably pointed back, just as the surviving manuscripts of Catullus and Plato, altered by scribal recopying over the centuries, had a common ancestor. From this premise arose the concept of culinary authenticity, of getting things right in the kitchen, reproducing the foods of France or Italy just as innocents abroad like me and thousands of other young American travelers experienced them on their home grounds, guided by experts like Julia Child or Marcella Hazan, meticulously faithful to tradition. But as a firmer sense of the history of cuisines came over me, I slowly came to see that the food I’d eaten in contemporary Europe had evolved throughout the modern period. Certainly the food of Europe before Columbus, tomatoless and potatoless, was nothing like the European food universe we knew, with its salades de tomates, potages Parmentier, and on and on and on. You couldn’t even push back the dawn of authenticity as far as 1850, once you began looking at cookbooks and other documentation of food eaten in the nineteenth century and comparing it with the food of our day. This turned out to be true even for societies assumed to be glacially traditional, such as China and India.

But in the summer of 1960, it was bliss to believe that the cuisines I had been informally studying on a shoestring in restaurants all over western Europe were as immutable as the conjugation of Latin verbs.

I walked back from Maxim’s to my Left Bank fleabag, stopping at a café for a game of pinball (le flipper). By then I knew the drill. First you asked the cashier for change—de la monnaie, if from a five-franc note; more often, you exchanged a franc coin for five twenty-centime pieces, cinq pièces de vingt, worth about four U.S. cents each, enough for five games (parties). Then you wormed your way next to the crowd of spectators around the Gottlieb pinball machine and plunked a coin down on the glass, asserting your right to play next.

One night I surpassed myself, flipping and nudging my way to a celestial score worth three free games. A tall North African had been watching me.

“Pas mauvais, monsieur,” he said. It was late. I had an early train to England and my flight home. I waved off the compliment and walked out, leaving the man to play my parties gratuites.

Two years passed. I studied more Greek and Latin. I spent another summer in Europe, three months filled with more classic meals, of which the highlight was a lunch with my parents and sister at France’s most important and historically pivotal restaurant, La Pyramide, in Vienne, on the Rhône south of Lyon. The food world knew this elegant, three-star establishment as Chez Point, or simply Point. Its founder, Fernand Point, had died in 1955, but his wife, Mado, kept the place going without any decline that a naive twenty-year-old could perceive.

I was also unaware, as I suspect were most of the guests filling the sunny terrasse of Point in late July 1962, that Chef Point’s legacy of light sauces and uncluttered plates would live on in the kitchens of his former apprentices, Paul Bocuse, the Troisgros brothers and virtually every other future star of the nouvelle cuisine. What struck me was the foie gras en brioche. I had eaten pâté de foie gras before, usually an inert pink spread scooped out of a can. But inside this flawless brioche, the Point kitchen had inserted fresh unadulterated foie gras. On the plate was a deceptively unimposing round slice of liver surrounded by a golden ring of bread. The taste caught me by surprise. This, I saw, was the real thing, the rich and refined goose liver that all the fuss was about.

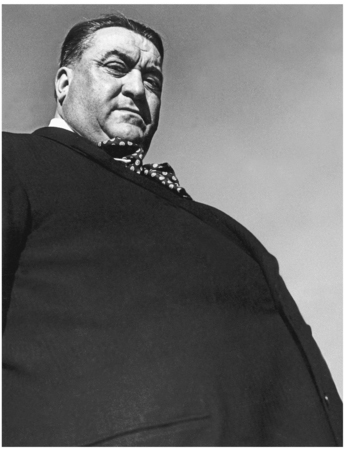

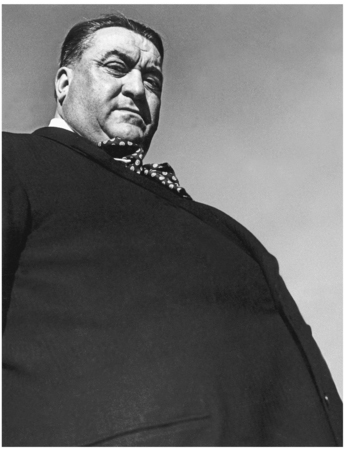

Fernand Point, 1947: He purified the language of the French kitchen and passed on his leaner cuisine to the young chefs who then created nouvelle cuisine. (illustration credit 1.1)

I can’t recall the rest of the meal, only the very end, when my father discovered that his wallet was missing. He thought he must have left it in the car. I was sent out on a search mission. There it was on the driver’s seat, unmolested.

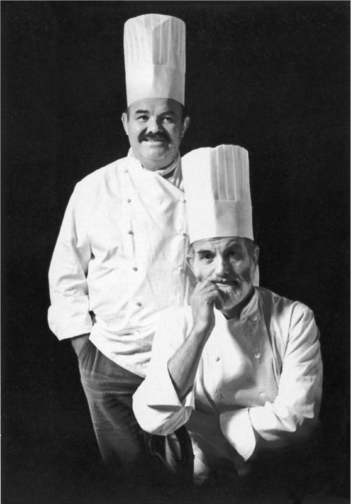

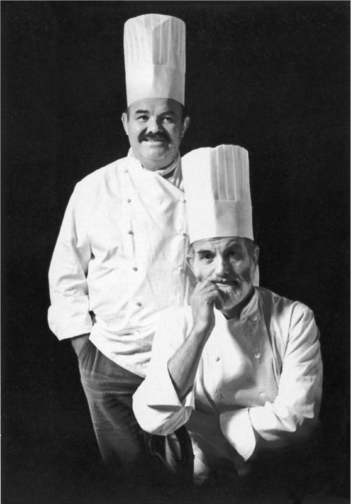

Pierre (standing) and Jean Troisgros. In the pokey cattle town of Roanne, these former Point acolytes served the most radical and witty menu of the postwar period. (illustration credit 1.2)

If I hadn’t been so anxious about the wallet, I might have looked up the street and seen the Gallo-Roman pyramid (really an obelisk) that gave the restaurant its name.

By legend, Point had once tried to resolve an argument between two customers right there where our car was parked. He’d persuaded two men who were fighting over the lunch bill to take their loud dispute outside and decide the matter by racing on foot to the pyramid. The winning runner would pay the bill.

Point was the starter. Off the men ran. And ran and ran and ran, until they disappeared into the afternoon.

Back in Cambridge, I found senior year an abrupt culinary letdown but a big step up in the interpersonal relations department. By Labor Day I was married, and with the marriage came a kitchen. Mostly, my wife did the cooking, without any expectation that I would help out except with the dishes. But I did get my hand in, crucially, in the summer of 1964, in the easy weeks between my Fulbright year of reading classical greats at Wadham College, Oxford, and the onset of classics graduate school back at Harvard.

Our apartment was in student housing, across Kirkland Street from the home of Julia Child. I saw the already legendary Julia from time to time in the neighborhood. We even shared a butcher, Jack Savenor, a genial sort eventually accused of overstating the weight of his meat.

Julia and I didn’t meet then, but I had her book, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, volume one. And I had the time to try its most challenging recipe, cassoulet, the Provençal bean stew with its numerous meats. In following through with more determination than finesse every one of its densely hortatory six pages, Margaret and I joined an avant-garde of ambitious home cooks whisking their way to authenticity with Julia as their chef.

Oh, yes, that cassoulet was a delicious success, and its combination of deliciousness and technical perfection, made possible by a recipe with consummate completeness and authoritative manner, reinforced my belief that great food was food prepared in the most traditionally accurate manner, with no crass substitutions like dried mushroom soup as a sauce base or inert mayonnaise spooned out of a bottle, and, on a higher plane, no deviations from tradition.

Long before the political scientist Francis Fukuyama declared that history had come to an end, every serious disciple of Julia’s already had concluded (actually, without any specific instruction on this point from Mrs. Child) that the history of food had ground to a halt at some point before World War II. Culinary classics were a heritage we could study, but neither we nor the great chefs of Europe, who had learned the classic repertoire during long authoritarian apprenticeships, were going to tamper with the treasures in this edible museum.

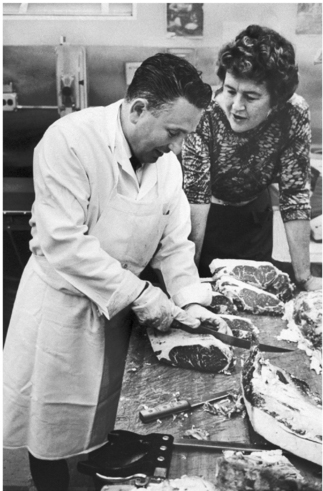

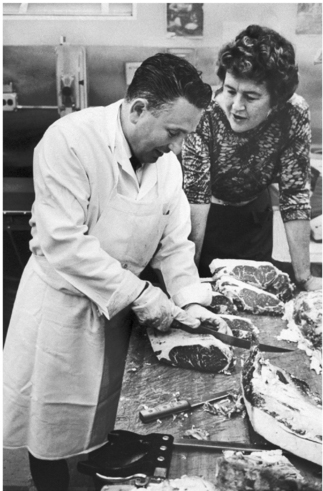

Julia Child and her Cambridge butcher, Jack Savenor, 1966. I bought meat there when I was a Harvard graduate student in 1965, but I was too shy to introduce myself to my favorite cookbook author. (illustration credit 1.3)

There was, for example, only one basic way to assemble a roast of veal Prince Orloff. Julia’s recipe starts with a reference to the master recipe earlier in the book for casserole-roasted veal. For veal Orloff the finished roast is sliced and then reassembled after being coated with a mixture of two sauces: soubise (pureed onions and rice) and duxelles (minced mushrooms). The reassembled roast is then coated with a third sauce: Mornay, which is a béchamel, or white sauce, thickened with cream and then flavored with grated Swiss cheese.

Julia spent a total of three detailed pages on this, but the professional chef’s manual Le repertoire de la cuisine of Théodore Gringoire and Louis Saulnier (1914), a shorthand aide-mémoire based on Escoffier’s Le guide culinaire (1903), which was still very much in use in later-twentieth-century French restaurant kitchens, dispatched the dish in four lines. But Gringoire and Saulnier prescribed intercalating the sauced slices with black truffle slices, and you were also sent scurrying to the specifications for garniture Orloff, a bevy of four intricate side dishes to be arrayed around the roast. Change any of this and you might as well have tried to pass off a cat as a dog.

What now sounds like stultifying fidelity to a tradition dating back not to the time of Vercingetorix, after all, but merely to the nineteenth century (to some point between 1856, when Czar Alexander II made Alexei Fedorovitch Orloff a prince in gratitude for his services as a diplomat in France, and Orloff’s death, in 1862, when a celebrated French chef working in the princely kitchen in St. Petersburg invented veal Orloff) was universally accepted as the primordial state of French cuisine, immutable and for the ages. Perhaps no one ever said such a thing, but that is my point. Questions of historical change simply didn’t come up. When they did, the notion of tradition and authenticity as granitic, almost prehistoric, unraveled and evolved into a more dynamic view of the origins of the cuisines we know.

I will confess that the prelapsarian, ahistorical point of view appealed to me. The idea that the world’s greatest systems of cooking had not and would not be turned inside out by modernism, as literature and painting had been, attracted me just as strongly as the forever inviolable and unevolving literatures of antiquity had pulled me in.

Plato and truite meunière were both classics, in basically the same sense.

That is what I would have said if you had asked me about it back then. Anything worth calling a cuisine was as solid as a sedimentary rock built up over generations and centuries through the accretion of human experience in one culture over time. Of course, I wasn’t stopping to think about all the constant change that had led to the supposedly granitic cuisines in existence circa 1970—the New World ingredients so seamlessly absorbed, the hundreds of dishes invented and published by nineteenth-century chefs like Antonin Carême. Perhaps because the previous sixty years in cooking had been stalled and kept from evolving by two world wars, an intervening depression and a slow recovery after the fall of Hitler, food history did seem to have ground to a halt. It was easy to believe that we had received a complete and unchanging constellation of recipes and foodways in the form of a cuisine, French or Italian and so on, that had its variations, as, say, ancient Greek had dialects, but the inherited aggregate, whether the Greek in dictionaries and in the surviving texts or French cooking in cookbooks or in surviving practice, was a finite system.

I fell into this way of thinking in Greek K, Harvard’s class in advanced Greek composition, and I imbibed it at the feet of my undergraduate thesis advisor, the ascetic apostle of “slow reading,” Reuben Arthur Brower.

Ben Brower had been my unofficial intellectual guru since freshman year. He was the senior faculty presence in Humanities 6, one of the general education courses you could choose from to satisfy a requirement Harvard created after World War II, to make sure that students didn’t emerge from the increasingly specialized world of undergraduate instruction without a broad sense of civilization, especially Western civilization. Hum 6 tackled this job by teaching a method of literary criticism spun off from the rigorously ahistorical and objective method of reading sometimes called the New Criticism. Less dogmatic and radically skeptical than the French deconstructionism that did its best to kill the enjoyment of literature for a generation of student victims in the 1980s, Brower’s version of New Criticism was really an invitation to pay close attention to the text you were reading. For a classicist—and Brower himself had started out as a classicist—Hum 6 wasn’t all that different in approach from the philological analysis of Greek and Latin that scholars had been practicing since Hellenistic times.

For Brower, as for those early editors of Homer who clustered at the great library of Alexandria, a text was an enclosed, fixed object inviting purification and explication, not subjective reaction. Brower was himself not much given to subjectivity. The one overt expression of strong feeling I ever witnessed from him was therefore a real shocker. The week the television quiz show scandal broke around the Columbia English teacher Charles Van Doren in the fall of 1959, Brower walked into our small “section” class of Hum 6 (Harvard attempted to counter the formality of large lecture courses like Hum 6 with regular sections that permitted students to discuss the course material with a faculty member, usually a teaching assistant, but my great good luck had been to land in Ben Brower’s own section) looking troubled. “What do you think of this Van Doren business?” he asked the class. There were various reactions, which eventually petered out. We were waiting to hear from Brower. He looked at the back of the little room, over our heads, and said, “If it were me, I would kill myself.” Then he directed our attention to a passage from the book we were reading closely together, E. M. Forster’s Where Angels Fear to Tread.

During senior year, I met with Brower nearly every week in the grand study-library that was his office in Adams House, the undergraduate residence where he was master. We talked of many things besides my thesis on The Odyssey, which he read with the same scrupulous attention he gave to all texts. It was a terrifying scrutiny—which, since he undoubtedly applied the same high standards to his own writing, explained in some measure why his scholarly output had been limited over the years, limited but diamond hard and exemplifying authority.

What I remember most clearly from those meetings was something Brower said about Greek composition, probably in reaction to my complaining about Greek K, which I found a dry exercise in turning English paragraphs into pastiches of Plato’s Greek. Following the custom of centuries of students in this deliberately uncreative discipline, we were constrained to use only the exact vocabulary, grammatical constructions and syntax that Plato himself, the acknowledged master and model of classic Greek prose, had used.

Brower defended precisely what I deplored: “What would it mean to improvise an ancient Greek sentence? Greek is not an ongoing enterprise. It is only what the ancient Greeks wrote. The sole reason to compose sentences in Greek today is to revive, as best we can, their language, so that we can feel it as our own. That—in theory, at any rate—makes us better readers of Plato.” There was no arguing with that. There was never any arguing with Reuben Arthur Brower, gentle man, with adamantine soul.

The lesson took. So when I thought about classic French food, another seemingly finite body of received culture, it was natural for me to think of it as I had been trained to think about dead languages. This was not a good analogy. As I soon realized, the most cursory look at early French cookbooks revealed a universe of cooking far removed from the haute cuisine system that grew up in the nineteenth century and that we had inherited in the form codified by Escoffier, a system that would shortly dissolve into a kaleidoscope of new, shimmering ideas before our dazzled eyes.

Even regional “cuisines” turned out to have histories. The “classic” dish of the Auvergne, in central France, the puree of potatoes and cheese called aligot, could not have been older than the introduction of potatoes into France from the Andes after Columbus. According to one theory, it was “originally” made with bread instead of potatoes, by monks who gave it to pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela. Similarly, in Spain, gazpacho in its present tomato-based form could not have been cooked before the sixteenth century and probably emerged much later. Cervantes’s gazpacho is not ours.

Pizza has a history, too. Of course, everything has a history. But that is not what was in my mind in the 1960s when I was discovering the food of Europe and the rest of the world. The historical attitude would come later. And I was also not describing the reality of my experience as an eater in those years when I maintained that my ecstatic gorging was some sort of cold-blooded investigation of a vast archaeological museum of human food culture.

In fact, I was just eating whatever piqued my interest, in restaurant after restaurant, country after country, region after region—and trying to taste as many dishes as I possibly could. I’m sure I never gave a thought, in the summer of 1960, my first time in Europe, to cuisines as calcified legacies. I was, of course, eating my way through the cuisines of Europe, but unsystematically, happily devouring the menu at hand.

My approach, instinctive, rabid and utterly natural, had much in common with language learning. As a matter of fact, I was operating in the same indiscriminate, sopping-up mode with French that summer, taking in every new word that came along, looking each one up obsessively in the dictionary, forcing myself to check every word I didn’t know in the paperback of Dumas’s La dame aux camélias I’d bought from a bouquiniste on the Quai Voltaire near my hôtel garni, thus acquiring a large vocabulary for discussing tuberculosis and coughing.

In restaurants, I acquired a huge new vocabulary of dishes, andouillette, marcassin, cou d’oie farci aux lentilles, râble de lièvre—none of which I had eaten before, or even known about in English; nor would I see them in America for decades. These dishes were a bit like the words for tubercular conditions in Dumas: not likely to be useful in my daily life in the States but part, nevertheless, of a growing collection of factoids that entered my consciousness, my self.

Obviously, my food experiences contributed more than lexical entries to my memory of those meals. I tasted every one of those dishes with gusto and could still give you a vivid account of the flavors and textures in many of them. But those sensations—the ugly technical term for them is organoleptic—were not the important ones. For me, they never have been of primary importance, except at the time I was experiencing them. What mattered most was the dish, in all its aspects.

Take sole meunière. Yes, I love this flat white fish’s tender, smooth flesh and the way its mildness is set off by the lightly browned butter and the acid of the lemon juice it’s cooked in. Because I have eaten the dish many times, I’m able, as a critic, to judge a restaurant’s specific presentation, comparing it against others from my past. But even that kind of judgment rests primarily on my sense of what defines the dish, of what might be called its Platonic form in my mind.

I am thinking of a canonical sequence: four boned fillets dredged in seasoned flour, quickly sautéed tableside in browned butter, which, just as the fish is cooked through, sizzles from the addition of the lemon juice. It is this sizzle, at the climax of the waiter’s enactment of the dish, that defines my sense of sole meunière. I am also interested in the epithet meunière, collapsed from à la meunière, in the manner of a miller’s wife. Like many French names for dishes, it is probably entirely fanciful. But the philologist in me can’t help wondering if there once was some kind of connection, in folklore or in a chef’s experience, that honored a miller’s wife’s way with a saltwater fish that was clearly not pulled up from the family millrace. Perhaps it was the flour coating, the miller’s product.

Other people no doubt give their organoleptic memories pride of place. Not me. I am, first and last, attracted by the concept of the dish, its definition, the kinds of information you’d find in Gringoire and Saulnier’s Répertoire de la cuisine or, for a more detailed description, in a standard recipe.

I have a philologist’s sensibility. I see an unfamiliar term on a menu and I want to order that dish, add it to my vocabulary. In 2009, at the excellent Chicago restaurant Spiaggia, I spied the unfamiliar word pagliolaia on the menu. The waiter said it meant “dewlap.” I thought of the hounds in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “Their heads are hung / With ears that sweep away the morning dew; / Crook-knee’d, and dew-lapp’d like Thessalian bulls; / Slow in pursuit, but match’d in mouth like bells.”

Spiaggia cooked its dewlaps with diver scallops and wild mushrooms over a wood fire. I ordered the dish, amused that a midwestern chef was one-upping the trend for beef cheeks started by Mario Batali in New York with an even more arcane part of the bovine head. In my review, I hewed to the organoleptic: “The hearty beef fragments and earthy fungus highlight the slippery elegance of the seafood. Having dewlaps myself, I winced for a minute but surrendered to the brilliance of the conception and the resourcefulness of Spiaggia’s butcher.” I did not disclose my white-magical motivation for ordering pagliolaia, which was to learn a new word by consuming the thing itself.

Did I realize back in 1960 or in the next two decades that I was approaching food in this way? Undoubtedly not. I thought I was ingesting cuisines, cultural artifacts frozen like the smiles on archaic Greek statues. And when the smile melted, when those gelid monoliths changed shape before my eyes, I continued to see the change as a systematic mutation, a wholesale revolution, which it was. But the revolution expressed itself through individual dishes, one recipe at a time. And that, of course, was how I experienced the nouvelle cuisine and every one of the later convolutions that have transformed the way we eat, and continue to transform it.

After I passed my PhD orals at Harvard, in the spring of 1965, I got a chance to explore French food in great depth. Instead of supporting myself as a teaching fellow in Cambridge while writing my dissertation, I accepted a job as a correspondent in Newsweek’s Paris bureau. In the early mornings before the office opened, I researched the scholarly literature on Theocritus at the Bibliothèque Nationale. Later in the day, I researched the menus of French restaurants.

Newsweek had hired me because someone at the magazine believed it would locate abler staffers at America’s better college newspapers than it was finding among older journalists at professional papers and magazines. This turned out to be a false theory, in the sense that almost every one of the Harvard Crimson–hatched trainees except me left Newsweek for law school or other greener pastures after a short stint at the magazine.

Fully expecting that I would return to academia, too, with a completed thesis, I went to work in the Newsweek offices off the Champs-Élysées. I ought to have been very busy, chasing news while simultaneously plowing through the scholarly literature on Hellenistic poetry of the third century b.c. In fact, I had almost no news to chase, and the Theocritus scholarship was almost completely irrelevant to my specific interest in the father of pastoral poetry’s creative reuse of rare Homeric words. Previous researchers had not spent much time on this question, which allowed me to flip through and discard hundreds of articles brought to me by disgruntled stack “boys” of advanced age every weekday morning. Soon there were no more tomes to check out. I had stumbled onto untilled ground, but by then I had lost interest in academic life and tabled the thesis.

In the bureau, I was the fourth of four correspondents, and the youngest by far at twenty-four. In the French idiom, I was the office benjamin (after Joseph’s youngest brother in the Old Testament). In practice, this meant that, aside from reading seven daily newspapers and thirty magazines, I had almost nothing to do. The other three correspondents, better connected, more skilled and more aggressive, hogged all the available work. And there wasn’t much of that, considering the very small amount of its precious space that Newsweek would allot to a backwater like France in a normal week.

Even French reporters didn’t have much of a story to follow then, because France under President Charles de Gaulle was essentially a benevolent dictatorship. De Gaulle had a chokehold on the news. In this quasi-totalitarian atmosphere, a very junior American correspondent had almost no chance of breaking stories major enough to interest a stateside editor. I had to plead to get the bureau to submit my name for accreditation to the only major event of my two years in France, a De Gaulle press conference, which one of the veteran correspondents would actually cover.

Yet I was a full-fledged foreign correspondent with a very official-looking clothbound press card and, fatefully, an expense account. So I busied myself with entertaining “sources” (most often just friends with marginally newsworthy job descriptions) at restaurants of high gastronomic quality. No one in the office minded. In fact, the bureau chief seemed glad not to have me nagging him for work, and it amused my colleagues that I was putting so much energy into establishing contacts in corners of French life they had no time to investigate.

When I left for a job in the New York headquarters, in 1967, the bureau gave me a copy of the antiquated but still respected Larousse gastronomique as a token of my colleagues’ respect; or perhaps it was their mildly scornful recognition of my being a person for whom food was a passion.

I had eaten at the big-name restaurants, the three-stars, which were venerable exercises in period performance. Chez Maxim was all deco froth. Lapérouse specialized in Gilded Age naughtiness, with dining alcoves that could be closed off from public view by pulling a drape to hide you and your poule de luxe. The Tour d’Argent gave you a card inscribed with the number of the canard à la presse they had just served you. Mine, I believe, was the 22,987th to be crushed and exsanguinated in that calf-sized silver device that glittered at one edge of the dining room high above the Seine with its famous view of Notre-Dame. On the street level was an actual museum, featuring menus from the Paris Commune of 1871, when the Tour d’Argent had served its besieged patrons with the flesh of animals “liberated” from the zoo of the Jardins des Plantes, a few blocks away.

The closest a fin bec could get to a creative sensibility in a high-end Paris restaurant in 1967 was either at glamorous Lasserre, near our office, or at Chez Garin, the remarkable bistro near my Left Bank apartment. Lasserre had a mechanical roof that opened to the sky in warm weather, to provide relief from the heat and to clear the accumulated Gauloise smoke from the elegant room. Tables sported costly articulated metal birds, which the intoxicated sometimes tried to purloin, under the waiters’ watchful eyes. It was part of the fun to see some pinstriper caught red-handed with a glittery peacock or snipe in his briefcase. The food was first-class and vibrantly cuisiné, showing the hand of a chef not yet ready for the mortuary.

Garin wasn’t so flashy, but for a lot of money you got top-flight versions of conventional cooking tuned up and rethought, sometimes with enough complication so that they really edged across the line into haute cuisine, or made the boundary between bistro and haute cuisine seem beside the point. Gael Greene ate there in May 1972 for New York magazine, about the last moment when any major French restaurant could still elicit ooh-la-las for trout stuffed with a pike mousse. The influence of the nouvelle cuisine’s great young chef Michel Guérard was already visible, if unavowed, in the two vegetable purees (celeriac and string bean) that Garin served Ms. Greene as a garnish for a split grilled kidney.

Just five years earlier, the nouvelle cuisine revolution had already begun simmering in the provinces. My bureau chief, Joel Blocker, proposed a story about someone named Paul Bocuse who was making news just outside Lyon. Joel struck out with his Bocuse proposal, but he would have been able to win space in the magazine for another modern French chef also trained by Fernand Point, if sudden political news hadn’t sidetracked him and forced him to send me instead to a small town in Alsace for the announcement of a third Michelin star to L’Auberge de l’Ill in tiny Illhaeusern.

Although the article on the restaurant that appeared in Newsweek’s April 3, 1967, edition was unsigned, it was nonetheless my debut as a food writer. The food I ate on this fateful assignment included a spit-roasted poularde de Bresse with truffles and golden Alsatian noodles. I have no memory of how it tasted or what it looked like, but it was clearly an attempt by the chef, Paul Haeberlin, to combine the very best chicken he could find with a luxury ingredient necessary to legitimize the dish as worthy of three stars, a cooking method that set it apart from everyday oven-roasted chicken. The noodles, a regional specialty, added handmade, local distinction. This, in itself, was a daring modernism, a belated nod to the automobile age. Haeberlin had bet his future that garnishing his signature chicken with humble noodles instead of an array of elaborately turned vegetables out of the Larousse gastronomique would appeal to Michelin’s modernizing inspectors.

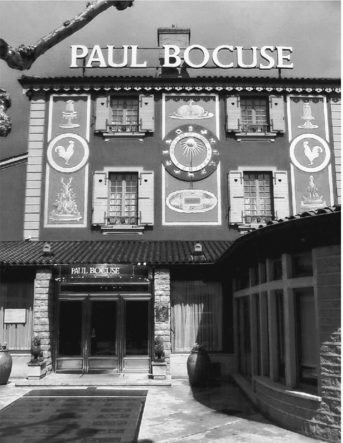

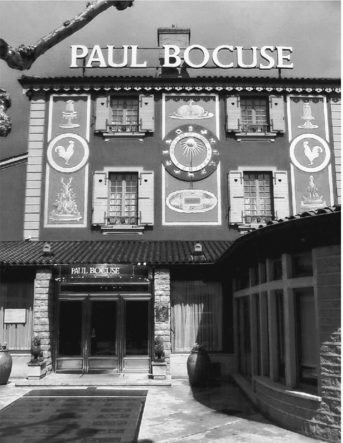

Restaurant Paul Bocuse at Collonges-au-Montd’Or, which features culinary innovation in a flamboyant atmosphere. (illustration credit 1.4)

This discreet nod to the Auberge’s remoteness from Paris, in a village so small it had no hotel, in a province whose identity was not securely French, would have resonated immediately with the Michelin inspectors looking for a rationale to justify adding this modest-looking hostelry to the pantheon of twelve three-star temples it had been enshrining almost without change for years. But, as neither they nor I could have said at the time, this dish, semiotically complex as it was (high/low, rustic/elegant, cosmopolitan/regional, French/German), would not count, when examined by hindsight anytime after 1972, as a forerunner of the radical changes soon to disrupt French kitchens. History was accelerating for chefs.

For me, the Illhaeusern reportage was important and memorable because of two other historically trivial reasons. It gave me a taste of food journalism, and it gave my son Michael, then on the verge of two, a taste of a really good soft-boiled egg.

I was traveling with him and my wife, Margaret, because the assignment had burst upon me on the eve of a skiing vacation. We piled into a rental Peugeot station wagon and drove due east through Nancy to Alsace. I had left Margaret and Michael in the hotel at nearby Ribeauvillé, thinking it would be unprofessional to bring them along for an interview at the restaurant. But when Jean-Pierre Haeberlin, Paul’s brother, who ran the front of the house, learned they were nearby, he insisted that Margaret and Michael be fetched for lunch.

Paul prepared a special meal for our infant, the egg and some remarkable mashed potatoes. When the egg appeared, Michael took a look at the amazingly reddish-orange yolk and exclaimed, “Apricot.” A gourmet had announced himself. When he finished eating, two school-age daughters of Jean-Pierre’s came out in regional costumes and led our boy upstairs for a nap.

Could this kind of unaffected hospitality survive the onslaught of adult gourmets in diamonds and limos? Jean-Pierre Haeberlin was justifiably worried. He said (and Newsweek quoted him):

We want to keep our simple country spirit, but from now on everything will have to be more expensive. We’ll need more help, a wider cheese selection, nothing but the choicest fruit. The higher prices will keep away some of our local clientele. To make up for that, we’ll have to draw many more tourists and that means we’ll be dealing with a more modish crowd. Between you and me, I don’t think we’re ready for the third star yet.

It was also a moment of challenge and change for me. Despite this minor triumph in Alsace, and a more significant professional success with an interview I extracted from Orson Welles when his Shakespearean film Chimes at Midnight opened in America, my career as a Paris correspondent had not flourished. I brooded over that with the typical paranoia of someone working at the periphery of a large organization. Was I being stifled by a hostile bureau chief who felt I had been foisted on him by his bosses in New York? I thought so. And when Jack Kroll, the senior editor in charge of cultural coverage, invited me to return to New York and work for him in the “back of the book,” where I had flourished as a trainee two years earlier, I did not hesitate to accept his offer.

Margaret was too far along in her second pregnancy to fly, so she and I and little Michael booked passage on the France. The meals were grand. I remember one breakfast with retrospective astonishment: course after course, including an omelet with asparagus tips peeking coyly out from one end and kidneys roasted in their own fat. Mostly, we slept between meals. A Frenchman we met on board attributed this doziness to the gentle undulation of the ship. “Le tangage,” he said. “Ça endort.” (The ship’s pitching puts you to sleep.)

I blamed the duck at lunch.

After five halcyon days on a sunny, placid North Atlantic, we landed at the docks on the West Side of Manhattan on my twenty-sixth birthday, August 1, 1967, unsure if I’d made the right decision.

I knew that if I had stayed on much longer in France, I would likely have made my life there. My spoken French was taking over my English as the language in which I found it easier to express myself. So much of my brief adult life had occurred in French. There were already subjects I had first learned about in the language. We had made friends. Michael was becoming a French child.

When I’d made the decision to leave Paris, it had seemed clear that if we did not return home then, we would likely find ourselves increasingly confirmed as expatriates. This vision had a certain appeal for me. I had worked hard to adjust to Paris and was proud when the very senior French reporter Michel Gordey told me that summer that I had made a good “début.” But it wasn’t enough. For a grandchild of refugees, “expatriate” was just a fancy word for “immigrant.” And however fluent and idiomatic my French became, it would always be a second language for me. There would always be words whose genders I’d be unsure about, cultural references I wouldn’t get, anti-American remarks I’d feel obliged to object to even if I basically agreed with them. Worst of all, my child would be a native speaker—in fact, a native in all respects except his place of birth. And I would be the slightly awkward foreign parent, subtly out of place.

Yet we felt just as dépaysé in those first few weeks in New York. Homeless, with a birth just weeks away and a confusing and ill-defined new assignment at Newsweek, I was as anxious about my life as ever. The apartment we found was a charmless box in an ugly newish building. Its windows looked out on the building behind. Through them, we could see a couple our age conducting their lives just a few yards away.

One of our first nights in this place, my parents came to dinner. Midway through the soup, Mother gasped and pointed to the window. Our neighbors were demonstrating the missionary position. They kept it up through our main course, interrupting their revels from time to time to sweep the floor and comb their large mutt.

Dinner out in Manhattan was much less exhilarating. We had been right to suspect the worst of the restaurant scene there. The bistros, a sorry gaggle of tired, hackneyed little dumps clustered near the theater district, served depressing retreads of clichés such as canard à l’orange or coq au vin. After trying one or two, we headed for the top, La Caravelle, which turned out to be a stylish oasis for high-society diners. Town & Country magazine had recently published a map of the restaurant’s seating plan, complete with the names of chic patrons at their favorite locations in the room. We expected to be seated in the inner clutch of undesirable tables known as Siberia. We did not expect to find the menu as uninspiring as it was. Worst of all, we did not feel as though we were in a French restaurant of the sort you’d find in France, even though the menu’s first language was French, as was the language spoken by the waiters.

Among the hors d’oeuvres at Caravelle (as at most of the other high-end French restaurants in town) were those pike dumplings known as quenelles de brochet, elegant specialties of Lyon virtually ubiquitous in the New York culinary stratosphere. There was a simple explanation for the curious local passion for quenelles. Behind them, and the menus at almost all the top French restaurants, lay the remarkable success of one man, Henri Soulé. He had created the restaurant in the French pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair and then re-created it as a permanent restaurant in 1941, Le Pavillon, having acquired special immigrant status for himself and his staff as war refugees. Quenelles were a Pavillon trademark.

They also became a trademark of the various spin-offs and clones of Le Pavillon that sprang up in the ensuing decades. Soulé’s snobbery was a defining part of what passed for haute cuisine in New York. He whored after big money and big names and sent those he considered nobodies to his back room. The already alienated ordinary gastronome could not help but see a tinge of anti-Semitism in Soulé’s most celebrated mistreatment of a customer, his vendetta against Harry Cohn, who was the landlord of Le Pavillon but couldn’t get a good table there.

The sole exception to the Soulé spirit in fancy French restaurants in New York in 1967 was a classy but not frosty restaurant in the garden of an East Side town house called Lutèce. The chef, André Soltner, had been a rising star in Paris when the French-American perfume heir and bon viveur André Surmain hired him to come to America and open a great restaurant. Lutèce, in my opinion at the time, was the only authentic French kitchen of high quality in the city. It was also not fragrant with disdain for its customers. The reason for this, according to Soltner’s main competitor, Roger Fessaguet, the chef at Caravelle, was that nobodies were the only clientele Lutèce could attract. Fessaguet told me in an interview in 1973 that there were only two serious French restaurants in New York, his and Lutèce: “We get high society and Soltner gets everybody else.”

This was a major exaggeration by that date, but it was certainly the case as late as 1971, when I met a man, Jewish but apparently not too happy about it, who confided to me that it was hard to take André Surmain seriously because he had changed his name from Sussman. There was also the problem of André Soltner’s accent. It wasn’t “really” French. He was Alsatian and sounded vaguely German when speaking English.

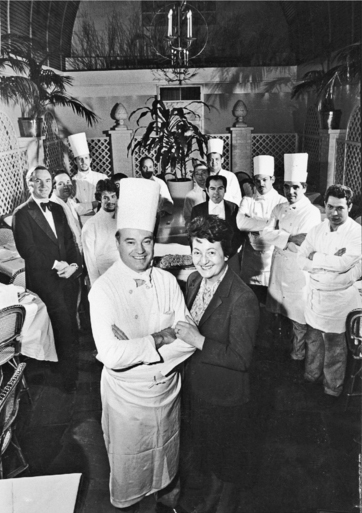

André and Simone Soltner with staff, 1981. This was Lutèce at its zenith, the nation’s best restaurant and the last fully French establishment to occupy that position. (illustration credit 1.5)

The other food I did come to love in those days in New York was a special kind of Chinese food, the spicy cuisine of Sichuan Province. There were no Sichuan restaurants as such yet, but Sichuan dishes had begun appearing at the Four Seas, located not in Chinatown but on a dark corner at the edge of the financial district on Maiden Lane.

The Four Seas restaurant was the project of a Chinese-Brazilian shipping magnate named C. Y. Tung. He was a fan of Sichuan cuisine and saw to it that a handful of typical Sichuan dishes appeared on the otherwise northern Chinese menu of the Four Seas. I was taken there by friends from graduate school, the sinologist John Schrecker and his wife, Ellen, who had eaten the real thing in Taiwan and eventually brought back with them a cook born in Sichuan.

All of this—the tyranny of Soulé’s snobbish mediocrity, Soltner’s scorned superiority, the occult rise of Sichuan cooking—struck me as good material for an article, and I wangled an assignment at New York magazine. The piece got as far as galley proofs before it was spiked because of a revolt by the magazine’s permanent food staff, which included Gael Greene, a bodacious Detroiter from my old neighborhood, and her “underground gourmet” colleagues, the graphic designers Milton Glaser and Jerome Snyder. New York’s legendary editor Clay Felker exhibited no shame in telling me this, and he then went on to question my expense account as excessive. I was indignant. Whether he relented on the expenses, I do not recall. But it was clear—I was told directly by a New York managing editor—that, because of my prickliness, Felker had blacklisted me.

I had already been published as a food writer in 1965, in Newsweek, with a review of a cookbook, in which I included an account of a meal I’d cooked from its recipes. The Connoisseur’s Cookbook, by Robert Carrier, was a compendium of food served at the American expat’s trendy London restaurant, Carrier’s. The review was signed. It was my debut in the food field, and the only published credit as a food writer I could show, when my life took, as they say, a dramatic turn.

I’d spent most of my time during that period reviewing books for Newsweek. They tended to be serious books, novels by Philip Roth, exposés of the State Department. I also wrote cover stories about important writers: Ross Macdonald, Norman Mailer. I had a nice life.

Then one morning in the spring of 1971, another Newsweek cultural writer, Alex Keneas, came into my office with an idea so preposterous that I didn’t even bother to reject it. I immediately forgot what he’d said.

What he said was: “Craig Claiborne is retiring as food editor of the New York Times. You should apply for the job.”

Alex knew this because he had once worked as an editor on the society-obituary desk at the Times and he was still in touch with old friends at the paper—and he was aware of my obsession with food. As far as I was concerned, however, I had no claim on the most important job in American food journalism. I was, in today’s terms, a foodie, but not a food professional. Certainly, I couldn’t have gotten the Times to listen to me on my own, even if I had wanted to be a food critic.

But Paul Zimmerman could. Paul was Newsweek’s film critic, and, in an earlier phase, he had once interviewed Charlotte Curtis. The two of them, neighbors in Greenwich Village, had ended up as friends. Alex told Paul about his suggestion to me. Paul, whose dining experiences in Europe the previous summer I had helped plan, believed I would be an excellent replacement for Claiborne. He called up the redoubtable Curtis, who was under serious pressure from Claiborne to find his replacement so that he could get on with launching an independent newsletter.

One morning in the winter of 1971, Zimmerman came into my office and said, “I’ve been talking to Charlotte Curtis about you and the Times food job. She’d like to take you to lunch. Here’s her number.”

I called it. Why not? (Fateful words.) Why wouldn’t I want to be taken to lunch by the acerbic and powerful Miss Curtis?

We met at La Côte Basque, Henri Soulé’s second Manhattan restaurant, a gift for his mistress, Henriette Spalter, known in the restaurant trade as Madame Pipi, because, I was told, she had started out as the ladies’ room attendant at Le Pavillon.

True to form, for a Soulé restaurant, the best seats at La Côte Basque were those near the street door. Charlotte and I sat at the table closest to the entrance, practically in the coat-check room.

The subject of food never came up. But Leonard Lyons did. He was cruising the dining room, pad in hand, gleaning tidbits for his syndicated New York Post gossip column, “The Lyons Den.” We dodged his questions. A few minutes later, a bottle of white wine arrived, the gift of a turbaned Romanian dowager at a table a few feet away, who wanted to know who the young man with Charlotte Curtis was. We dodged her question, too. Farther down the wall of banquettes, I espied two luminaries well known to me who I hoped wouldn’t espy me. They were Kermit Lansner, the editor of Newsweek, and Katharine Graham, chair of the Washington Post Company, which owned Newsweek.

Charlotte dropped me back at Newsweek in a cab that couldn’t have taken more than three minutes to cover the ten blocks downtown from La Côte Basque. It was time enough, however, for her to get to the point: “You could probably have this job if you want it,” she said. “But since you’ve never written about food or restaurants, you’ll have to do some tryout pieces. We’ll pay you for them, of course, and cover your expenses. The whole thing will be completely confidential. Are you interested?”

“Why not?” I replied.

Where was the harm? Why wouldn’t I want to eat out on the Times and get paid for my trouble, which amounted to writing three short pieces that couldn’t be spiked because they weren’t supposed to be printed? It all seemed like some surreal lark. I assumed the Times would never hire me.

I told my wife exactly that. And my colleague Charles Michener also told me exactly that. His Yale friend Bill Rice, who had professional food training and lots of food clips, was clearly a better candidate.

But we were both wrong.

A few weeks after the Côte Basque lunch, after I’d handed in two restaurant pieces and an interview with Piper Laurie, then the wife of Newsweek’s movie critic Joe Morgenstern, about her baking skills, Charlotte Curtis called me at home. I was in the Forty-second Street library checking citations for a book I’d translated from French to be called Imperialism Now. It was an updating of Lenin’s 1917 tract Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism written by a French economist of Maoist tendencies called Pierre Jalée. His previous book had been The Pillage of the Third World.

I had spent hundreds of hours at this task for a pittance, acquiring a transient competence in French financial lingo, including the French equivalents for “mutual fund” (fonds communs de placement) and “carbon black” (le carbon black). My publisher was a Nigerian, and his firm was called Third Press. I’d met him at a party and agreed to translate the Jalée book so that I could tell my lefty friends from Harvard, who accused me of selling out to the capitalist press, that I worked for Newsweek to support my Maoist activities.

This is not what I told Curtis. When I called her back, she wanted to know why I was in the library. I made something up.

“Congratulations,” she said.

Pause.

“You are going to take the job, aren’t you?”

“Why not?”

I was born on the eve of war and Holocaust on August 1, 1941, at Harper Hospital in Detroit. By family legend, I began eating immediately and with prophetic zest. The exact content of that first meal is unrecorded, but I am sure it didn’t come directly from Mom. She, like other advanced women of her time, believed that science offered a nutritionally superior and more hygienic way to feed her baby than she could herself.

I was born on the eve of war and Holocaust on August 1, 1941, at Harper Hospital in Detroit. By family legend, I began eating immediately and with prophetic zest. The exact content of that first meal is unrecorded, but I am sure it didn’t come directly from Mom. She, like other advanced women of her time, believed that science offered a nutritionally superior and more hygienic way to feed her baby than she could herself.