Five

With Reservations

Shortly before nine on the morning of September 11, 2001, I leashed my dog, Duncan, and took him out for a walk in Greenwich Village. As we emerged from our gate onto Barrow Street, I looked left and right to make sure we wouldn’t collide with a runner or surprise another dog. The coast was clear, but to my left I noticed a crowd of people standing in the middle of Seventh Avenue, facing south, downtown, and staring up. I joined them.

Shortly before nine on the morning of September 11, 2001, I leashed my dog, Duncan, and took him out for a walk in Greenwich Village. As we emerged from our gate onto Barrow Street, I looked left and right to make sure we wouldn’t collide with a runner or surprise another dog. The coast was clear, but to my left I noticed a crowd of people standing in the middle of Seventh Avenue, facing south, downtown, and staring up. I joined them.

The north tower of the World Trade Center, hooded in smoke, had, as we eventually learned, been gored by American Airlines Flight 11, which smacked into its north face just below the building’s top at 8:46 a.m. The sky, as everyone remarked, was eerily clear and blue, but even so, the second crash, of United Airlines Flight 175, into the south face of the south tower, between floors seventy-seven and eighty-five at 590 miles per hour at 9:03, although witnessed by our crowd in the street and by millions on television in real time, came from the opposite side of the towers and was easily mistaken for the exploding fuselage of the first plane.

Duncan and I went home to watch the coverage of this awfulness on television. I was shocked like everyone else that morning, of course. But since I was physically unharmed and not acquainted with any of the actual victims of the attacks, it took several months before I understood that 9/11 had had a decisive, violent effect on me. It ended my perfect life at the Wall Street Journal.

The Journal’s offices had looked directly at the Twin Towers from across West Street. Every weekday morning, when I wasn’t on vacation or traveling for work, I took the No. 1 subway to Cortlandt Street and walked through the Trade Center underground concourse to our offices in Battery Park City, the enormous office and apartment building complex erected on landfill salvaged from the excavation for the towers.

For me, the Trade Center was not just something I saw from my office. I had had a direct personal and professional interest in the original excavation for the towers and in their construction. The World Trade Center’s architect, Minoru Yamasaki, had been based in Detroit when I was growing up there. At the end of high school, I took his daughter Carol to the movies. The Yamasakis lived in a very American suburban house not designed by the architect, but he had put his stamp on the place with a traditional Japanese sand garden in the front yard. It disconcerted me on the summer night I came to pick up Carol Yamasaki, as did her grandmother, in a kimono, who thanked me at the door for being “so kind” to Carol.

So I felt kindly toward the Yamasakis, in turn, but I had not been able to avoid feeling a chill whenever I passed the brutalist towers and the inhumanly empty and cheerless space around them.

While the World Trade Center was still a construction site, I had gotten an assignment from the New York Times Magazine to write a piece about the revolutionary food-service system planned for the Twin Towers by the legendary restaurant impresario Joseph Baum. Because of construction delays, I nursed that assignment for two years, hovering around the site until I could eat in the ingenious coven of intimate eateries that flowed one into another on the concourse, as well as in other more formal restaurants on higher floors, an integrated food-service network that culminated, literally, in Windows on the World, 106 floors above what eventually became Ground Zero.

My first meal of many at Windows was a preopening staff lunch, at which I interviewed the chef, who served me, as a sign of especial respect, part of the liver of a deer he’d shot over the weekend. It was raw and purple. Six Windows employees, including Baum’s acerb and brainy consultant Barbara Kafka, were watching me. I bolted the organ, still icy from the refrigerator, slice by slice, in a panic relieved only by the site of the spike of the Empire State Building’s broadcast antenna piercing the ocean of clouds three miles uptown, which blanketed everything else in Manhattan except it and us in thick fleece.

Milton Glaser, the eminent graphic designer who had collaborated on Baum’s complex project, had copied the sky around us on a brighter day for the ceiling of a restaurant on the seventy-eighth floor, where there was a barber I went to for the view over the Hudson from his chair.

I did not make it to lunch in the towers on February 26, 1993, the occasion of the first terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. As lunchtime drew near, in order to pass the time until guests from Santa Fe arrived, I was listening on earphones to a recording of the original version of Arnold Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, which was written for string sextet, when, at 12:18 p.m., a boom blasted through the music. My first thought was: This piece is not scored for tympani. Then I looked out the window at my right elbow: smoke was pouring out of a ventilation baffle in the street nine floors below. Islamist terrorists had exploded a 1,200-pound bomb in a Ryder rental van parked in the underground garage of the Trade Center. Six people were killed. Smoke filled the towers, and fifty thousand were evacuated.

My intrepid New Mexican friends had been moving upward on an escalator to a covered bridge spanning West Street when the explosion hit and knocked out power to the escalator. After pausing for only a moment, they walked up the stalled stairway and continued on to my office. We ate in a little place on the water in the World Financial Center. I’ve forgotten its name and menu, but not the TV monitors over the bar, which dropped their usual fare of stock market news for coverage of the disaster across the street. Survivors, their faces black from smoke, trickled in steadily. With each arrival, applause broke out and we, the unharmed, bought them drinks.

After 9/11, the Journal opened offices for its staff in temporary locations all over Manhattan. Our least fortunate colleagues were exiled to the company’s sprawling and cheerless complex in South Brunswick, New Jersey. Our page moved with the neocon editorialists and the Weekend section to a loft space in the garment center. I would never return as a staffer to 200 Liberty Street after the building was decontaminated and rehabbed, many months later. My job was eliminated in a brutal budget cut that did not stem the accelerating decline of the Journal’s fortunes, until its sale to Rupert Murdoch in 2007.

Getting forcibly “retired” in May 2002 did not surprise me. Even before 9/11, I had foreseen the future. In the spring of 2001, virtually every journalist over sixty on the paper, the core of its institutional memory, took early retirement. Then came a redesign and a restructuring, which reduced the presence of the Leisure and Arts page (“my” page) in the Journal from five days to three. We did pick up space in Weekend, but it wasn’t really ours, in name or spirit, and our location on other days had been shifted from a key spot in the A section to the new fourth section, Personal Journal, a catchall of personal finance advice and soft news.

My job had shrunk in scope almost by half. Either someone was going to figure it out and fire me or I’d be twiddling my thumbs at my desk. One way or the other, I was going to need something to fill the slack time. I signed a contract with Susan Friedland at HarperCollins for a compendium of 101 recipes every literate cook should know (I asserted), which appeared in 2003 as The Cook’s Canon. I also arranged to re-up as a classics graduate student at Harvard in order to finish my long-abandoned PhD.

It wasn’t as though I had been brooding guiltily about that unfinished dissertation ever since I had forsaken classics for the Paris bureau of Newsweek in 1965. But I had never been able to cut the cord completely. From time to time, I would reread a book of Homer or Vergil (Book IV of The Aeneid for the Vergil bimillennium in 1970), and I couldn’t bring myself to toss out the notes for my thesis on rare Homeric vocabulary in Theocritus, hundreds of three-by-five cards in a hinged maple box.

Then one night in early 2001 I ran into John Van Sickle, a Harvard classicist who had fetched up at the City University of New York. He handed me an offprint of his latest article on Vergil. I read it and noticed that the footnotes were full of references to lively-sounding recent work on the sources for Vergil’s Eclogues, short pastoral poems modeled after Greek poetry of third-century B.C. Alexandria.

I mentioned this to John and observed that my notes for a thesis on Theocritus, the leading poet of the proto-Vergilians in his article, had survived the years in my attic.

“Why not give them to me?” he asked.

If this had been a scene in a comic book, a lightbulb would have gone on over my head. I thought: If a distinguished senior scholar like him is interested in them, maybe I should consider using them myself.

I checked. Even after thirty-five years and a boomlet in Hellenistic studies, no one had stumbled onto my thesis idea. Way back then, I’d noticed how Theocritus worked stunningly unusual Homeric vocabulary into his Idylls, which were very un-Homeric short poems about lovesick shepherds or other highly unepic, unheroic material. Those rare Homeric words stuck out like drawn swords at a tryst in a sheepfold.

An ancient reader from Theocritus’s circle of scholar-poets at the Alexandrian library could not have missed these Homeric nonce words. Hellenistic literati knew The Iliad and The Odyssey by heart. So when they saw a word Homer had used only once in a contemporary poem, they would have automatically connected it with its original location in Homer. Just as automatically, they would have compared the two contexts in their minds, the original and the Theocritean. The pinpoint verbal link would have spotlit the contrast between Homer’s bloody heroic universe and the soft, love-besotted pleasant retreats of Theocritus’s bucolic brave new world.

I called the Harvard classics department to find out if my graduate work from the sixties was still valid toward the PhD. The secretary had no idea and referred me to the university registrar, who showed no surprise at all to be discussing readmission with a man who’d dropped out thirty-seven years before. They sent me a green, single-page form. I sent it back. There were three other requirements.

First, I owed the richest learned institution in the world a $150 “reactivation fee” for every term for which I had not registered. This would have amounted to $11,100 for the seventy-four terms I’d been AWOL, but there was a cap of $1,000. That I could afford.

Second, I had to submit an official copy of my graduate school transcript bearing the seal of the university. To accomplish this, I sent a $3 check by snail mail to Harvard’s archival division, which sent me back the transcript, also by snail mail. I then put the transcript in another envelope and mailed it back to Cambridge, to another university office a short walk from the place that had issued the transcript. So much for the information highway.

Finally, and most challenging, I needed a letter of recommendation from a member of the department. Every professor I had known was dead, except for one. Wendell V. Clausen, my original thesis advisor, was seventy-eight and, though retired from a very eminent career as a Latinist and student of Hellenistic poetry, he was also emeritus and therefore technically still a member of the department.

He wrote the letter. I was readmitted, earlier than I had expected. But I had to finish work on The Cook’s Canon before I could start on the dissertation. So I spent a year researching 101 classic recipes I thought should be part of everyone’s culinary background, before I dived into reading all the scholarship on Hellenistic poetry that had come out since my flight from antiquity in 1967.

Then I wrote the thesis,* without any of the career anxiety that had made me leap to the safety of Newsweek in 1965. And I got the doctorate in 2005—June 9, to be exact. I even attended commencement in the Harvard Yard and sat in the front section once again (the right side, reserved for PhD’s, instead of the left, for undergraduates, where I had once shared the front row with the other AB summas), close enough to see porky Harvard president Larry Summers peer with half-shut beady eyes out on the thousands of students and their guests. Henry Louis Gates was up on the dais, too. I’d seen him the week before at Columbia University, at the awards ceremony for the Pulitzer Prizes. “My” film critic at the Journal, Joe Morgenstern, had won the prize for criticism, the only Pulitzer “my” page had won in two decades. Nothing, apparently, became my career at the Journal so much as my leaving it.

You may be wondering why I didn’t take my shiny new degree and find a job on some leafy campus teaching the young about the aorist optative or the joy of Sextus Empiricus.† Well, I really wasn’t interested in teaching anywhere but Harvard, and Harvard wouldn’t have me. I asked Richard Thomas, the head of the department, who had been on my dissertation committee, if I should apply for a job I’d learned about in an ad in the Times Literary Supplement of London. The minimum requirement was a dissertation in progress, and I already had the degree. Richard replied, “We’re looking for someone for the long haul.”

I was, by then, sixty-five years old, but far from senile, just too foolish not to have recorded this exchange, which would have given me a case to sue Harvard for age discrimination.

I did teach one semester at Columbia, which taught me once and for all that I had no aptitude or inclination for teaching. And, anyway, by then I was too busy traveling around the country trying out new restaurants for, yes, the Wall Street Journal.

Once again, I had been unexpectedly lured back into food journalism.

The enticing Mephistopheles who did the luring was Tom Weber. I remembered him as a young Journal reporter I’d met just after he’d gotten the go-ahead to do a piece on interactive porn websites, which meant he could tell models to do kinky things to themselves from the comfort of his Journal workstation. This would normally have been a firing offense, but Tom had obtained a license to ogle from his editor and he couldn’t stop telling anyone who’d listen about his new assignment.

He’d advanced beyond that kind of thing by the time he called me. Tom was the editor in charge of the Journal’s new Saturday Pursuits section, a love child of the Friday Weekend section with a major commitment to covering food.

Would I like to try reviewing restaurants for Pursuits? I said I would. And that was that. For almost four years, during which time Tom lost his job to a much less talented careerist, I continued to be the Journal’s designated diner, until the Murdochniks finally got around to thinking they might as well put their stamp on food, now that they had brought the rest of the paper up to their antipodean standard of excellence.

Their decision to eliminate full-dress restaurant criticism from the paper made a kind of sense. Very few readers could actually dine in the places I’d been writing about, even though I’d scattered my visits around the nation. And I’d been spending plenty of money, almost $100,000 a year, on travel and restaurants. But I had apparently managed to swim beneath the notice of the managing editor, Robert Thomson. When I’d run the Journal’s arts page, I used to joke that it was a bit like being the medical editor of the Christian Science Monitor. I had been able to enjoy something like the same freedom of ignominy as Thomson’s restaurant guy. The one time we met, at the insistence of one of his secretaries, he couldn’t seem to think of anything to say to me.

His apparently complete indifference probably kept him from noticing what a well-kept, globe-trotting servitor I was, and delayed his drawing the conclusion that someone jetting off to Vegas, Reykjavik and London in the same month, and earning the paper’s top freelance fee every other week, was someone whose work might be worth serious scrutiny. Eventually he figured it out, or somebody else told him my gravy train wasn’t the right vehicle for food in the weekend Journal, which he was revamping in the image of London’s Saturday Financial Times.

Even the best, most sympathetic editorial supervision isn’t often much better, from the writer or reporter’s point of view, than having a KGB minder with strong ideas about how his agents should do their jobs. But until Thomson’s predecessor had sent Tom Weber packing, I’d been reporting to a smart journalist who had a great many acute things to say about how my coverage of American dining should be shaped.

Weber pressed me into doing cover pieces for the section on the country’s best hot dog joints, its best burgers and its best barbecue. Weber also had inherited the old Journal’s passion for the “nut graf,” a paragraph high up in the story that summed up the point of the exercise and justified it. To me, this was a clunky interruption of the actual story, and I did my best never to force one into my columns, which meant that the editor I reported to directly had to make me write one or put one in herself. But I came to miss these bearable and sometimes genuinely helpful interferences after Weber left and was replaced with a regime that virtually never paid any attention to what I was doing, unless a reader made them think I’d committed an error worth correcting. After Weber, I never wrote a cover story, not even the projected takeout on America’s greatest pizzas, a plan that was swept aside after the Thomson regime decided to lead the section each Saturday with a topical essay of great length and deathless wisdom penned by a writer of renown.

In truth, I had begun to enjoy my pop-food odysseys. Going to Decatur, Alabama, to check out Big Bob Gibson’s barbecue was not that different from the trips I’d once taken so proudly in search of American folk food traditions for Natural History. And the very best purveyors of burgers and ’cue really did deserve the acclaim I could give them, and this, in a world of nauseatingly bad national chains and commercial rip-offs like Big Bob’s, was an honest blow for the stubborn practitioners of quality, tradition and, sometimes, worthwhile innovation, a blow I was happy to strike.

The travel itself was exhilarating in its weird mix of grinding discomfort, discovery of the delicious treasure previously unconsidered by the ballyhoo industry and bright contrasts between the grit of the subject and the corporate cash that subtended my efforts.

Take the Texas leg of the barbecue story. It started in utter expense-account comfort at the Four Seasons in Austin, with a vague plan to drive on to the Hill Country, a collection of small towns settled chiefly by German immigrants, where barbecued beef was the local religion and a lure for gastrotourists of all levels of income and refinement. That plan gained sharper focus over dinner in Austin with Louis Black, the cofounder and editor of the Austin Chronicle as well as the cofounder of the South by Southwest Festival. A native of Teaneck, New Jersey, who had been imbibing local lore and culture since his student days at the University of Texas, Black gave me a list of places, and I went to them all.

Fortunately, we got to Lockhart, the very best of the Hill Country barbecue towns, early in the day, before too many fatty brisket slices dulled our judgment. By then, on outings in Tennessee, Alabama and several other states famous for their brand of ’cue, I’d already stuffed myself with smoky renditions of pulled pork and pork shoulder, ribs and other slow-cooked animal parts, in dozens of self-consciously down-home joints with rolls of paper toweling standing tall on vertical holders, instead of napkins. So by the time I rolled into little, semigentrified Lockhart (pop. 14,237), I was, if not jaded, at least not remotely energized by the prospect of another plate of meat collapsing from its own weight among piles of cole slaw, baked beans or other canonical “sides,” followed by banana pudding bulked out with Nilla wafers.

It was, therefore, thoroughly remarkable that the beef brisket at Kreuz woke me up and changed my perspective on barbecue pretty completely. It was a paradigm shift.

Kreuz, pronounced Krites and referred to in some quarters as the Church of Krites, is, compared to the gaudy, shameless, huckstering, media-fawning baroque of Big Bob Gibson’s or Mike Mills’s 17th Street Bar & Grill in Murphysboro, Illinois, a monastic retreat. Kreuz does not sell sides. It has no special sauces (like the one so fetishized by Mike Mills that he likes to say he’d have to kill anyone who got hold of the recipe). In fact, it has no standalone sauces at all.

Smitty’s Market in Lockhart is even purer and plainer. In my first bite of brisket at Smitty’s, the smokiness was so strong it changed my idea forever of what barbecue could be. This style of heavily smoked beef may take some getting used to, but for me it is the zenith of the ’cue universe. That doesn’t mean I don’t love the pork barbecue other regions excel in. But Smitty’s is a temple of the pristine, a shaded cave of making, with its stark, black steel–doored smokers and taciturn pit men who stand in the heat of the post-oak logs, pull out a piece of brisket and ask you if you want it sliced from the lean or the fatty end. I went for the fatty and didn’t mind that Smitty’s is really not a restaurant but a specialized meat market. Out front, there is a shockingly bright, pathetic excuse for a dining room, which only makes the crepuscular Hades in the sooty pit area, which some genius implanted into an old brick brewery, seem even more wonderfully infernal. When you go through the door from this dusk to the fluorescent glare and the crappy tables of Smitty’s dining room, the transition is something like the shock Plato tells us his cave dwellers experienced when they emerged into the sun.

There are many things you might want to tell other people about Smitty’s, but the smokiness in the meat is the main lesson I learned that morning, and the thin pink line at the edge of each slice, which is the sign of the oaky gauntlet it has run for a dozen hours or more.

We drove on for the rest of the day, from the Hill Country, in central Texas,‡ all the way north into the tornado belt of Oklahoma, taking in that region’s barbecue specialties, hickory-smoked brisket, bologna and pickled mixed vegetables, at black places like Leo’s in Oklahoma City and Wilson’s in Tulsa.

Eventually, in the warm months of 2007, I followed the barbecue trail through twelve states and came away convinced that the bigger the hoopla, the more acute the disappointment. At the huge festival on the banks of the Mississippi called Memphis in May, I got sunburned and burned in general at the insulting scam, in which dozens of “famous” barbecue teams compete with their “famous” sauces and meats from their portable pits, but the thousands of ticket holders rarely get a taste of that “famous” meat, which is not for sale but prepared for the elite palates of the judges alone. We regular folk were invited to look on with our tongues out.

On a tip from a Memphis native—Edward Felsenthal, Tom Weber’s boss at the Journal—we drove to tiny Mason, Tennessee, east of Memphis, to Bozo’s, which is to barbecue pork as Smitty’s is to beef. At Bozo’s, you don’t need to sauce up the perfect quills of pork shoulder. Outside this unassuming family operation, a lonely whistling freight train rumbled by. The bright lights of the high-security prison next door cast an ominous shadow on the humble former farmhouse. Within, all was good cheer restrained by the confident reserve that results from knowing you can pull pork so that each strand comes away long and perfect, like hanks of moist beige yarn.

This was the Memphis style at its apogee, thirty-five miles from Graceland, and all the other sights and sounds of downtown Memphis. Bozo’s does not serve ribs. Don’t ask for brisket, either. In this shrine of the shoulder of the sow, aficionados know that “barbecue” signifies only one cut of meat, from high on the hog.

But you don’t have to stay in the backwaters of the South to find very good barbecue, because the appetite for this food has spawned fine pits all over the land—at Slows, across from Detroit’s derelict rail station; at the East Coast Grill in Cambridge, Massachusetts; and in Manhattan, at a clone of Kreuz called Hill Country.

Only in California did I strike out completely in my search for great barbecue. This was unfortunate (but perhaps an inevitable result of the overwhelming importance of Hispanic and Asian food in California’s vernacular food world) but I didn’t waste much of my time there. I sampled undistinguished ’cue in South Central Los Angeles, boarded a redeye and flew back to New York.

Even before the barbecue piece appeared in the paper, it made a splash. The online edition of the Journal was posted a bit before the newsprint broadsheet arrived at subscribers’ doors and desks. The paper attached an e-mail address to the piece so that readers could “interact.” And they did—many more than had ever written in about one of my articles in the pre-Internet era.

Reader reaction was only part of the Internet’s effect on me. As late as 2002, when I left my editing job at the Journal, the telephone had still been a major tool of research and professional communication. When I returned to the paper in 2006, I did almost everything online. Instead of wasting time on hold with reservationists, I booked online through OpenTable. To get a preliminary idea of where to eat in an unfamiliar town, I consulted sites from Zagat to Yelp. Since many of my early columns were, in effect, about food trends as they emerged on restaurant menus, I would search the cybercosmos for additional examples of a new ingredient or recipe I’d noticed by accident while dining out on assignment.

For example, I was surprised to see snails in a pasta dish at an Italian restaurant in New York. In my previous experience, snails had always been escargots, that cliché of retro French bistros—usually canned, swimming in garlic butter and, often, inserted into shells not originally their own.

Was the humble snail creeping out of this tired presentation? Were diners around the country confronting what might be called free-gliding snails, snails without shells and garlic butter, snails in omelets or snails with lobster?

They were. A quick Web search turned up creative snail dishes on several menus, including one at the innovative new regional Bluestem, in Kansas City. I flew in for dinner and, using the snail “trend” as a pretext, gave national attention to an excellent, quietly locavore outpost of first-rate food in the heart of the heart of the country. The headline: SLOW FOOD.

The discovery of the Internet as a powerful trend-spotting tool was a dangerous development. It was difficult not to believe that you could prove anything if you surfed diligently enough, even if that evidence was lurking somewhere on the 75,987th page of a Google search.

For the culture of dining and cookery, the Internet changed everything, just as it did in every other corner of life. But for a restaurant critic trying to operate nationally with no research assistant or other backup (and for those four years, I was the only food critic writing regularly and systematically in a major newspaper about the entire country, with frequent forays abroad), the Internet was indispensable, if only because almost every restaurant worth writing about had a website with hours, phone numbers, e-mail access for reservations, street addresses, maps and, most of all, menus. In the pre-Internet world of the early 1970s, I went out to eat without any clear idea of what would be available. The restaurant PR industry rarely sent me a menu, just vapid and information-free press releases. So I was reduced to stealing menus, as Craig Claiborne had advised, just to have a record of the meal. Those menus were also helpful to me as a reporter. When I wanted to interview a chef for a feature article, I could look at his menu and decide what dishes I would ask him to demonstrate for me.

Especially in dealing with Sichuan chefs who spoke no English, it was very useful to be able to point to a dish on the menu. I rapidly got used to arriving unannounced in a restaurant I had reviewed—calling ahead was useless, since the person at the other end could barely understand a simple request for a reservation. I would bring with me a set of measuring spoons and a measuring cup. Then I had to insert myself into the cooking process, so that I could get accurate measurements for the recipe I wanted to publish. Uncle Lou, the Sichuan master chef, was one of many cooks who suffered with friendly bewilderment the intrusions of the young man from the Times thrusting little spoons into his mise-en-place.

But that was the only way I could take home a recipe of his hot spicy shrimp (and all the other dishes from Sichuan I was the first person to publish in English). Then the scribbled notes would get transcribed into proper recipe form, with a list of ingredients at the top, in the order they were used in the numbered directions below, which were always followed by a “yield,” the number of servings you would get from the recipe.

Even in 1971, this recipe format had a whiff of the home-economics test kitchen about it. Julia Child had already evolved a more complex and comprehensible format, but I still prefer its straightforward structure, especially since I worked with it every day at the Times.

I did my own testing then, at home. If I made mistakes, they would be my own. Also, my kitchen was a much more realistic arena for testing recipes for readers who, like me, were cooking with conventional ranges, instead of the professional-style Garland behemoth in the Times test kitchen.

The recipe testing made me a much better cook. And I discovered that I enjoyed the time at the stove. I especially loved baking bread, with its long periods of waiting while the yeast did its magic in the dough. I would read a novel or write a piece. Then I’d have a better loaf than I could easily buy in that era (so hard to imagine now) before artisanal bakers had put crusty sourdough on the shelves of national supermarket chains.

By 2006, anyone who wanted a classic baguette or a ciabatta could just buy one in the neighborhood. I did not mind not needing to bake myself, since I was really too busy traveling for the Journal. And I certainly did not regret not needing to steal menus anymore. The last time I’d wished I had stuck one in my pocket was at dinner at Pierre Gagnaire’s Paris three-star establishment in the mid-1990s, where I’d found it tiresome to be taking notes in the dark during an almost comically intricate multicourse meal. I asked for a menu to keep. The captain refused point-blank and, only after I insisted, very grudgingly agreed to make a photocopy. They had a Xerox machine in the back office. Today, like virtually every restaurant of consequence, Pierre Gagnaire has a website with a menu on it. No one any longer needs to beg or steal a copy, or try to write down a jawbreaker dish name like that recent Gagnaire soup extraordinaire: Consommé de boeuf au Banyuls, salsifis caramélisés, topinambours à la moutarde de Cramone et glace de maïs (beef consommé with Banyuls wine, caramelized salsifys [oyster plants], Jerusalem artichokes with mostarda di Cremona, Italian candied fruit in mustard-oil syrup, and corn ice cream).

As a twenty-first-century food critic, I rarely ate a meal I hadn’t been able to plan in advance at the computer. And when I paid by credit card in the restaurant, the computer-generated receipt came with a separate little printout of every dish I’d ordered. And no waiter ever flinched if I pulled out a small digital camera and took a picture of a dish, which I could e-mail to my editor from the table for later publication.

Of all these brave new efficiencies, e-mail was by far the most important. I could file my stories instantaneously and receive back edited copy wherever I happened to be. Compare that to the way reporters filed to the New York Times from the field in 1971. We would call a number in New York and read our articles to a monitored recording machine, spelling every name and unusual word. And in many cases, the next contact we had with our dispatches was when we read them in the paper. Garbles and mistakes were inevitable.

The computer and e-mail changed all that.

What had happened, from my perspective as a classicist, was the elimination of scribal error. For the first time since the invention of writing, nothing needed to be copied. The text, once it had been saved as a digital document, could be moved into print or disseminated electronically with no risk of human errors being introduced, as they always had been since antiquity, first by scribes who had hand-copied every book until Gutenberg, after whom the job of copying was shifted to type compositors and their successors at the keyboards of linotype machines.

But with the computer, the blurring chain of transmission came to an end. The author’s version was, in principle, immutable and eternal. It could be revised, but the age-old need for the error-making scribe, the meddling keystroker, the secretary generating mistakes again and again through laboriously retyped versions of a letter or a chapter was finished. And no one would ever need to cut carbons again or risk the loss of years of work when a manuscript got left in a cab or burned.

I loved the computer and I loved e-mail even more. Especially because it brought me mail from readers who told me things I didn’t know. In their passion to set me straight or rant at me, they often broadened my scope and—the best of them, anyway—gave me ideas for new columns. And a columnist is always in need of ideas for the next column.

At Cranbrook School, in the vaulted dining room designed by Eliel Saarinen that we called the carbohydrate cathedral, the standard grace before the meal was “Make us ever mindful of the needs of others.” In the reverberating din of three hundred boys reciting that prayer, some of us would say instead, “Make us needful of the minds of others.” A juvenile quip, sure, but also an essential precept for all intellectual activity, one acutely necessary for a hack with space to fill every day (or in my case at the Journal, every other week).

After the barbecue cover, I received a helpful e-mail from Charles Perry of Birmingham, Alabama, who claimed most persuasively that I had unaccountably neglected the barbecued ribs of his region.

He wrote: “In a small town outside of Birmingham, Cahaba Heights (now part of the suburb of Vestavia), there lies a dark, carbon encrusted pit … surrounded by a quaint brick structure with concrete slab floors and grease stained walls from years of preparing some of the best slow-cooked swine one could ingest. Miss Myra’s BBQ awaits your review …”

Who could resist such a pitch?

Perry and his friend Jordan Brooks took me to three extraordinary shrines of the barbecue art: one in Birmingham and two in Tuscaloosa, an hour away, where they both had graduated from the University of Alabama in the previous century. Of the three ’cue temples we visited, Miss Myra’s Pit Bar-B-Q, in Birmingham, was easily the furthest from those shacks in the piney woods of Dixie where this most durable and rib-sticking of our regional cuisines was born. For example, it has a sculpture collection, a veritable museum of swine art consisting of hundreds of effigies of the genus Sus in all its pink, piggy majesty. This enthusiasm for porcine imagery didn’t prevent the cheerful staff at Miss Myra’s from subjecting the racks of a multitude of hogs to a moist indirect heat that produced ribs better than any I had eaten anywhere up until that moment. Miss Myra’s also turned out a sublime barbecued chicken and served white sauce (spicy mayo with vinegar).

We pressed on toward Tuscaloosa and the University of Alabama campus, holy ground for my hosts. “Can’t you feel your pulse quicken?” Perry asked me when we were still twenty miles away. Once there, we drove around the campus, stopping at the football stadium. “You’ll want to take your shoes off now,” Brooks announced. He was only half kidding. We paid our respects to full-length life-size statues of all the Alabama football coaches who’d had national championships, notably Paul “Bear” Bryant, in coat, tie and fedora, looking stern.

Then, like thousands of students and alumni, we went to Dreamland for ribs. The restaurant was founded in Tuscaloosa in 1958 by the aptly named John “Big Daddy” Bishop. On football Saturdays, Dreamland loyalists wait two and three hours to be served in this small but densely decorated unofficial adjunct of the university athletic department. The ribs are worth waiting for. Hickory gives them a milder smokiness than the post oak used in Texas, so Dreamland’s pit turns out a subtler taste of fire with peppy seasoning. And there is no white-boning; the ribs pull off the rack without falling off the bone, the classic indication of ideal doneness. Getting ribs to that point requires constant diligence and lots of poking around in a hot pit.

The best place to witness this precise cooking was at Archibald’s, in a nondescript location across from a pallet factory in nearby Northport. Archibald’s was, and I say this with respect, a real, mythic ’cue shack. The green clapboard walls weren’t falling down, but the boards were definitely not plumb. The pit was a concrete-block affair attached directly to the small building. And a stack of wood sat a few feet away.

“You know the barbecue is good if the woodpile is bigger than the restaurant,” Perry said.

The ribs were very crisp outside, moist inside. Betty Archibald served them in a pool of orange, vinegary hot sauce. Their taste stood up nicely to the sauce. The side dishes here were literally on the side—of the wall next to the pit. Little bags of munchies. The ribs were what counted.

All three of us marveled at Mrs. Archibald’s intensity. She kept opening the pit’s door and fussing with racks of ribs, moving them around with a pitchfork.

That kind of hands-on, personal, obsessively careful cooking also produced my number one choices for the hot dog and hamburger covers Tom Weber had commissioned me to write for the Journal. Both Speed’s, the Boston hot dog genius, and Miss Ann, the hamburger dowager empress of Atlanta, operated on the smallest possible scale, following their own special method for improving on dishes served with less distinction elsewhere on a frighteningly vast scale. They both shunned publicity and showed no interest in maximizing profits or branching out. (Miss Ann was positively bitter about the assault of customers my article brought her.) I sniffed them out from various friends’ tips and from persuasive recommendations on the Internet. Similar advice led me to dozens of other little places, but Speed and Miss Ann stood out, way out and above the others.

Speed sold his hot dogs when it pleased him in Newmarket Square, which is not some historic New England green space on the model of the Boston Common but a triangular parking lot surrounded by bleak wholesale food warehouses in the unfrilly purlieu of Roxbury. His “restaurant” was a food truck with a makeshift kitchen in it. Speed himself was a quietly gregarious older man, said to have been a fast-talking DJ in the day, whence the nickname he goes by instead of his real name, Ezra Anderson. He was friendly and leaked his secret recipe to me with a conspiratorial half-wink.

Speed confided that he coaxed such wonderful flavor out of a run-of-the-mill commercial dog by marinating the dog in apple cider and brown sugar. Then he grilled it over charcoal. Actually, this octogenarian entrepreneur let his young apprentices handle the dogs under his watchful eye. They also toasted the buns. By legend, the piquant relish he supplied along with raw onions and beanless chili to pack into his split franks was another Speed treasure made by the man himself.

Speed was palsy and open; Miss Ann ran her little shop like a tough schoolmarm. When it was full, customers had to wait on the porch until those already seated finished up and left.

Ann’s Snack Bar occupied an unpromising lot on a broken-down industrial stretch of highway. Miss Ann worked alone at her grill, patting each ample patty lightly as she set it down to cook. Her masterpiece, the “ghetto burger,” was a two-patty cheeseburger tricked out with bacon that she had tended closely in a fryolator.

Observing Miss Ann in action would have been enough of a show to take a visitor’s mind off his hunger. But while the lady demonstrated the extreme economy of motion of a superb short-order cook, she simultaneously carried on a running dialogue of lightly sassy repartee with customers she knew.

In mid-sentence, Miss Ann would dust your almost-ready patties with “seasoned salt” tinged red from cayenne pepper. It looked like a mistake, too much, over the top. But when you got your ghetto burger in its handsomely toasted bun envelope, you regretted doubting her for one second. The big burgers stood up fine to the spice. And they just barely fit in your mouth.

Miss Ann. Speed. Betty Archibald. Did I pick them because they were colorful loners at the margins of mainstream America? Sticking a finger in the eye of the fast-food industry was never my goal, but it was inevitable that I would prefer idiosyncratic, independent cooks with a special spin on the most widely cooked dishes in American culinary life. Interestingly, all three of them turned out to be black and elderly. Each time I’d embarked on one of those cover stories, I’d been convinced the project was bogus. I couldn’t imagine that even the best burger or ribs or dogs would be worth the kind of hype a cover piece in the Saturday Journal’s Pursuits section would require. And then Speed and Ann and Betty Archibald would turn the whole silly business of claiming I’d found the nation’s finest examples of its favorite foods into a crusade for recognizing talent and craft.

As I traveled more and more as a restaurant critic, I saw that ambitious restaurants had sprung up in almost every city. Yes, the density of New York’s restaurant culture surpassed that of other cities, but my experiences on the road persuaded me that the dining life in Chicago offered more adventure and excitement. And that Las Vegas was a far more interesting food scene than what a discriminating traveler might encounter in Los Angeles or San Francisco. Even more surprising were the dozens of remarkable, sophisticated restaurants I started finding in “flyover” towns like St. Paul and Boulder and even Duluth.

No can say with certainty how what was not so long ago a gastronomic wasteland between the coasts turned into a happy hunting ground for the sophisticated eater. But it seems clear that, starting in the late sixties, a critical mass of information and training kept growing. Food-minded tourists came home and began to cook the food they’d tasted on its home ground, guided by authentic and practicable recipes that put the foods of France (Julia Child), Mexico (Diana Kennedy), Morocco (Paula Wolfert), Sichuan (Ellen Schrecker and, much later, Fuchsia Dunlop), Italy (Marcella Hazan and many others), Greece (Diane Kochilas), Spain (Penelope Casas) and the Middle East (Claudia Roden) within reach of home cooks. Professionals could train seriously in various schools around the country, most of which hadn’t existed in 1970.

Many of the most ambitious students spent time in European restaurants as apprentices to famous chefs, an opportunity that had barely existed in the old days. When they returned home, the hugely enlarged network of quality restaurants gave them interesting work and a chance to burnish their résumés.

Grant Achatz, born in 1974, grew up in a family restaurant business before attending the Culinary Institute of America, which landed him a job at the French Laundry, from which he rose to be top chef at the pathbreaking Trio in Chicago, a stepping stone to his even more radical, molecular-gastronomic megasuccess Alinea, also in Chicago.

Najat Kaanache, born in 1978 in Spain of Moroccan parents who worked in agriculture, abandoned a career in acting for culinary school in Holland, where she apprenticed with François Geurds, a former sous-chef under Heston Blumenthal at the three-star Fat Duck, outside London. To consolidate her training, she arranged stages under Achatz, René Redzepi of Noma, in Copenhagen, and with Ferran Adrià at El Bulli, north of Barcelona.

That almost all of her mentors are household names, at least in food-conscious households around the world, is a remarkable fact entirely apart from this young woman’s ability to navigate so sure-footedly in a global network of superstars. Still more remarkable is that this network exists and that its biggest names transcend national borders, influence one another and reinforce the culture of food that has fostered their careers.

At the weeklong celebration of Charlie Trotter’s twentieth anniversary as Chicago’s most honored chef, in 2007, six other world-beating chefs cooked the main banquet. Adrià was in the kitchen, as was Blumenthal, who stole the show with a pictorial and auditory shore dinner. He hid iPod Shuffles in whelk shells that sat next to a delicious seafood mixture on each of eighty guests’ plates, so that they could listen to sounds of the sea on earphones while they ate a complex seafood medley bathed in seafood foam.

This confraternity of stellar cooks was, even for the twenty-first century, a notable gathering of globalized culinary celebrity. But it was only the most glamorous example of a less public networking that connects the alert kitchens of our day, most concretely in the form of hot new recipes that spread around the cybersphere instantaneously and then end up in slightly varied versions on plates far from their origins.

In 1977, I caught an early glimpse of this on a tour of Michelin three-stars in France, where virtually every menu offered some form of early asparagus in oblong boxes of puff pastry. I was tempted to sleuth out which chef had started this mini-vogue, but what mattered was that all of them were so aware of this new idea and that they all had latched onto it that same month. And that was before the Internet.

By 2007, dozens and dozens of chefs, not just the mandarins of the French Michelin, were blithely appropriating the newest wrinkle, from the most distant kitchens, instantaneously, in cyberspace.

When Anne Burrell, a protégée of Mario Batali’s, opened Centro Vinoteca across the street from me in Greenwich Village, among the Italianate small-plate dishes on her menu was an intriguing pasta, a single large ravioli with a liquid egg yolk concealed inside. In the restaurant’s basement kitchen, I observed as a meticulous fellow called Humberto rolled out a long, thin layer of dough for the steroidal ravioli and cut out three-inch disks from it with a sort of cookie cutter. Onto them he spread a mixture of ricotta and Parmesan cheese. Then he cracked an egg, separated the yolk from the white and gingerly deposited a perfect sun of a yolk on the cheese. A second disk of dough went on top and was pressed in place to make a single large raviolo (“ravioli” is the plural), or, to be more exact, a raviolone (the last syllable, an Italian “augmentative,” implies bigness beyond the normal) with a raw yolk inside.

After a brief (say, three-minute) poaching in gently simmering water, the dough was barely cooked, as was the still-liquid, ready-to-burst-on-fork-contact yolk. When the raviolone was served upstairs, Burrell would emerge from the open kitchen to shave an ounce of white truffle over it.

Even without that pricey fillip, her delicate egg surprise was an established winner well before Ms. Burrell brought it to Seventh Avenue South. Long before she tried her hand at making one, this witty dish had helped earn the reputation of the great Italian restaurant San Domenico, at Imola, near Bologna.

From there, it had spread not only to my corner but across the country. Diners had reported encounters at Boston’s Prezza and at Prima Ristorante in Boulder, Colorado. Rising star chef Steve Mannino was stuffing his pasta pouches with quail eggs and wild mushrooms at the Las Vegas Olives, in the Bellagio Hotel. And at classy Fifth Floor, in San Francisco, before it got a Michelin star, Chef Melissa Perello had put her signature on the dish with a duck egg, porcini mushrooms, peas and serrano ham.

In another example of fast-moving recipes, at just about the time the egg raviolone was making the rounds, the lucky gourmet could find the same elegant butter-poached lobster recipe adorning tables at the French Laundry and at Barbara Lynch’s No. 9 Park, on Beacon Hill in Boston.

Circulating apprentices, food blogs, tweets and other Internet channels all were playing a role in the spread of food ideas. But the most powerful multiplier of food news and stoker of chefs’ ideas and reputations was undoubtedly television. It started with Julia Child’s black-and-white series The French Chef, which made her the first star of noncommercial TV. A few serious cooks flourish on television today, but it is impossible to imagine Julia making a career in the same shrill, crass universe reigned over by Paula Deen and others who didn’t make any major culinary mark before television brought them fame. Deen, exhaustingly exuberant, was, when I checked in 2006, on the air sixteen times a week and being watched by a total of seven million viewers as she demonstrated conventional recipes drawn from traditional southern cooking.

The lunch I ate at Ms. Deen’s equally popular Savannah restaurant, the Lady & Sons, wasn’t any good. But the crowd around us in that multistoried eatery that serves hundreds of meals daily looked happy enough, ratifying their fandom with knife and fork. Would they have been as happy eating better versions of the same regional food at a nearby tavern called Moon River Brewing Company (after the hit tune by Savannahian Johnny Mercer)? Would they have been as thrilled as I was by superb renditions and improvisations on these dishes at the Beard-award-winning Elizabeth’s, down the road? I’d like to think so.

Someday, I want to test the idea that everyone is born with a good palate. I would conduct the experiment on my own TV show, a culinary remake of The Millionaire. I’d find a lucky couple at a fast-food restaurant and whisk them off to some five-star temple, where I’d let them eat their way through the menu. At the Lady & Sons, I fantasized for a bit about that couple’s purrs of pleasure, until the reality show around me—equal parts Six Feet Under (dead victuals) and CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (unsightly victims of criminal cooking)—preempted my attention.

I walked swiftly by the tired buffet of southern fried chicken and soulful veggies. At the bar, I ate soggy fried green tomatoes and munched fitfully on a doughy biscuit while the couple next to me drank their meal and left with cocktails in hand for a trolley tour of the settings of John Berendt’s best-selling account of decadent Savannah, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

My main course consisted of stringy crab molded into an uncrisp cake. It reminded me of what I’d known all along: there’s no business like show business.

Deen on the tube is a superior cook to the Paula Deen whose actual food you eat in Savannah. Her recipes are perfectly respectable versions of southern home cooking. The entire stick of butter she likes to drop into the pan with a lascivious leer is no cruder than the river of beurre Joël Robuchon works into the mashed potatoes that helped vault him to the top of contemporary French cooking. Deen’s rise from humble beginnings as a purveyor of lunches hand-delivered by her sons is a winning yarn, no less convincing because it is true.

The trouble isn’t in the star, but in her success—that her restaurant is an insult to the very fan loyalty it sells out. The place is just too big. When Berendt wrote, in an introduction to The Lady & Sons Savannah County Cookbook in 1998, that the earlier restaurant offered “a short course in the meaning of Southern cooking—the flavors, the ambience, indeed the very heart of Southern cooking,” it had eighty-five seats. The Lady & Sons lost its soul when it moved, in 2003, into its 330-seat, fifteen-thousand-square-foot dining headquarters.

I experienced the gracious heart of southern cooking in Savannah, at Elizabeth Terry’s turn-of-the-century Greek Revival mansion just south of downtown. There the cheese biscuits had just come from the oven, nicely browned. There the crab cakes were nicely crisped and contained pieces of crabmeat that looked as if they came from crabs, not an industrial processor.

In the dining room, fitted out with Windsor chairs and trompe l’oeil murals of flowers and household objects, local food tradition was honored with such presentations as spicy shrimp and country ham in redeye gravy, flanked by wedges of fried grits standing on edge like sentinels. This fine thing, like the equally fine crab cake, cost $13.95, less than a dollar more than the crab cake at the Lady & Sons. You could, of course, spend considerably more on main courses at Elizabeth’s. The grouper special, an imaginative fantasia of local fish and vegetables, ran $33.95. Yet it wasn’t egregiously pricier than the Lady & Sons’ beef-and-tomato pie ($24.99).

The only things missing at Elizabeth’s were the pizzazz and lugubrious self-promotion of the Lady & Sons. The eponymous Elizabeth and her two daughters haven’t, so far as they have let on in the limited publicity they have released, suffered like Paula Deen from agoraphobia, been robbed at gunpoint or rallied from a divorce to find middle-aged romance with a bearded boatman.

I doubt, in other words, that food television, in its flamboyant new mode, is doing much for the encouragement of good taste and culinary knowledge in its public of millions.

Exposure on TV has surely benefited the careers of authentic talents such as Mario (“Molto Mario”) Batali, while the young chefs who prosper in the preposterous cooking competitions staged for television can leverage their ability to concoct a winning dish out of seven never previously combined ingredients into financial backing for a restaurant. But real creativity in the kitchen is not a stunt carried off under terrible time pressure. Indeed, creativity hasn’t been a central notion in the historical narrative of the kitchen, even, or perhaps especially not, in the development of haute cuisine, until the current period of chef worship and perfervid admiration of novelty.

I saw the effect of TV food shows at its worst at a wildly popular new restaurant in Chicago, Girl & the Goat, created by a Top Chef winner named Stephanie Izard. Girl & the Goat’s menu is a catalog of dishes straining for originality, a chaos of strong-flavored ingredients that knock one another out: kohlrabi salad with toasted almonds, and pear, and ginger dressing; or fennel potato-rice crepes with butternut squash, and shiitake kimchi, and mushroom jus.

In 2009, I got a chance to see a real top chef invent a dish, and it was a very different, careful improvisation. With over twenty Michelin stars worldwide, Joël Robuchon is arguably the planet’s most successful restaurateur. Three of his many branches have the red guide’s highest ranking, three stars: one in Macao, one in Tokyo and one in Las Vegas, in the MGM Grand Hotel.

Four times a year, Robuchon visits Nevada to redesign the menu at this fabulous, small pinnacle of gastronomy. I arranged to meet him there and watched him tweak a crab recipe for his new spring menu.

The world’s most decorated chef was drinking a Diet Coke as he entered the immaculate kitchen, followed by a small posse of underchefs. He inspected a small circular tin of osetra caviar and then pulled apart an Alaskan king crab the size of a puppy.§ “Where is the coral?” he asked, setting off nervous scurrying and whispers. Coral, the red, deeply flavorful female crab’s egg mass he needs for the sauce, was found in another big crab. The kitchen had previously prepared cooked meat from king, Dungeness and blue crabs, which Robuchon tasted in different mixtures, pulling out samples with his fingers. In the end, he decided on a mélange of king and Dungeness.

“For me it’s all about the texture,” he said.

The new spring menu was centered on shellfish. “Americans really love shellfish,” he told me, as if to congratulate me and more than 300 million other compatriots for our good taste.

He went on to build his new dish by layering the crab mixture with strips of yellow-brown Santa Barbara sea urchin, which he extracted from a neat pile. The crustaceans were only the beginning. Minced raw white cauliflower was also a major ingredient. It would lurk within the crabmeat mix as a stealth carrier of crunch, which Robuchon said he believes makes this dish a no-grain marine cousin of tabbouleh, the ancient Near Eastern salad based on bulgur wheat and mint. To carry the edible metaphor all the way, the chef added mint to his crab creation.

The diner who ordered this crab-and-cauliflower “tabbouleh” at the start of the 2009 spring menu received a small caviar tin, inside which only black osetra eggs were visible. But when he attacked them with his fork, the action unearthed a chamber symphony of crab, cauliflower and mint, the faux tabbouleh concealed under the caviar emerged, and everything merged on the tongue in the most unexpected and beautiful way.

“I just had this idea in my head,” Robuchon explained, without, of course, explaining anything.

On that same February visit, I returned to the jewel-box dining room adjoining but totally insulated from the MGM Grand’s casino, for the restaurant’s winter menu. No course included more than four ingredients, and the often surprising combinations did not war with one another. An egg yolk hid in an herb-flavored raviolo: there it was again, the San Domenico raviolone, raised a notch with a medley of black truffle shavings and orbs of baby spinach foam—two kinds of spherical shapes, one on a convex mount, the other in a concave container.

Then I got my favorite course, the frog leg fritter. This iconic food of France was presented as a single gobbet of flesh with a matchstick of bone sticking up as a handle—letting you pop the thing, with its crisp, bird’s-nest coating, into your mouth, but only after you’d dredged it through teardrops of garlic cream and parsley puree, chaste reminders of the dish’s origins in Provence.

I was equally amused and delighted to see how Robuchon ennobled the lowly turnip with candied chestnuts in a foie gras broth. The flavors and textures married as if centuries of trial and error had long since made the combination commonplace. Ditto for the very strange velvety soup of oats studded with toasted almond and red dots of chorizo juice—superior comfort chow pepped up with crunchy almond bits hiding in the porridge. Odd, too, and also magnificent was the “risotto” of soy shoots with lemon zest and chive.

Toward the end of the evening, the courses turned less fanciful. A piece of veal with a napoleon of vegetables and a natural herb gel preceded an exemplary bass, served unadorned except for its crisp skin and a dark red pool of sauce derived from verjuice, the acidic liquid pressed from unripe grapes. The breathtaking simplicity of these two main dishes only underlined how radical the earlier part of the meal had been. Then, just as I thought he was winding down, Robuchon at his trickiest conjured up a rococo assemblage called Le Coca.

As in cola.

This tribute to the chef’s beloved soda consisted of a ginger mousse, an ice made from vodka and Coke, and something dark, a bubble of Coca-Cola gelée crowned with gold. It was a grandiose joke, but Robuchon had taken the world’s most famous industrial flavor and transmogrified it into a high culinary essence—still recognizably Coke, but also something way beyond.

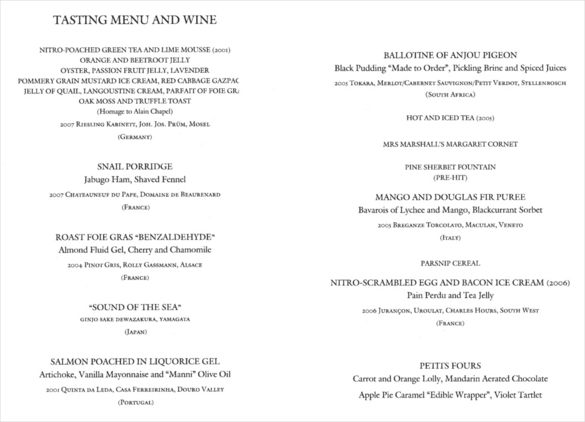

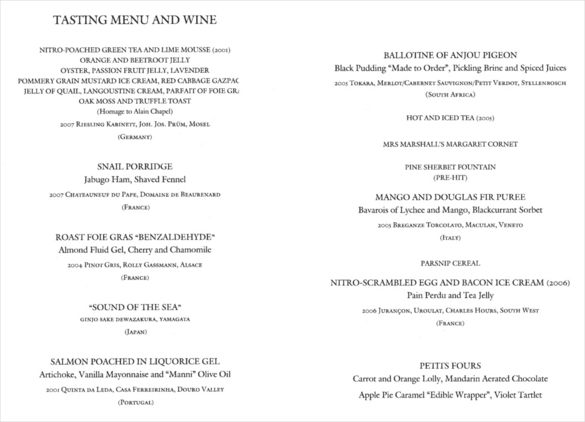

For a larger version of this menu, click here.

I ate my way through this menu from Joël Robuchon’s three-star Michelin restaurant in Las Vegas in 2009, after interviewing the world’s most honored chef in the little kitchen tucked inside the world’s largest hotel, the MGM Grand. The menu included a fantasy dessert based, with a magician’s sleight of hand, on Coca-Cola, Robuchon’s workaday drink of choice. (illustration credit 5.1)

That meal may have been the finest, and it definitely was one of the most creative, I ate in four years of free-range feeding at the summits of gastronomy. I was not surprised, since I had eaten in the same hidden Eden twice before. And in the course of many trips to Las Vegas, I had concluded that it offered the most intense opportunity to eat well in the United States and possibly in the world.

Robuchon had long ago given up on Paris for his fanciest flights. The economics of New York made it impossible for him to mount one of his “gastronomic” restaurants there. Even the New York branch of his more-relaxed Atelier chain folded in 2011. But in Las Vegas (as in that other gambling capital Macao, where he had won three stars with a similarly grand restaurant), he could count on support from the MGM Grand and from high rollers. This is why most of the big names in the restaurant pantheon have flocked to Vegas. Some, like Sirio Maccioni, of New York’s Le Cirque, have merely knocked themselves off without knocking themselves out to achieve something great.

And yet the stigma that surrounds Sin City keeps some of my most food-minded acquaintances from going there.

In 2005, when a crazed foodie I know well decided to take six friends to dinner with her first Social Security check, she picked Chanterelle, the once-great Tribeca address that was cruising toward its twilight. I suggested that if all eight of us pooled our Social Security checks, we could fly to Vegas, eat at Robuchon and fly home on the redeye, all without surrendering a dollar to the gambling industry or tainting ourselves with the vulgarity of the strip’s carnival architecture.

We went to Chanterelle.

My final wallow in the Nevada desert as Journal food critic, in early 2010, coincided with the opening of MGM Mirage’s City-Center, the sixty-nine-acre complex that nearly bankrupted Dubai. Gamblers were feeding the slots on the ground floor of the sixty-one-story Aria, the central property. Shoppers were trolling for glitz in Crystals, Daniel Libeskind’s cavernous funhouse of a mall. There was major league art everywhere, by Robert Rauschenberg, Jenny Holzer, Frank Stella and, from Nancy Rubins, a monumental assemblage of multicolored boats moored together in the central traffic island. But most enticing for me was the lure of three “fine-dining” restaurants masterminded by three famous chefs.

How did I pick this trio out of the dozens so toothsomely described in CityCenter’s advance publicity? They had to be outposts of very well-respected venues outside Vegas whose chefs had never worked there before. This may have been unfair to Michael Mina’s American Fish or Julian Serrano’s clever-looking celebration of Spain, named after himself, at Aria, or Wolfgang Puck’s bistro inside Crystals. But food news is food news. And the arrival of three-star French master toque Pierre Gagnaire in North America, as well as the Clark County debuts of Chicago headliner Shawn McClain (Sage) and Masayoshi Takayama (Bar Masa and Shaboo), wizard of rawness at Masa in Manhattan’s Time Warner Center, were the biggest news in this first season of CityCenter’s struggling but apparently viable leviathan.

If, however, the only restaurant you landed in here was Takayama’s Shaboo, you would have been on your Droid right away selling MGM Mirage short. Admittedly, Shaboo set the bar very high, even for the high-rollingest diner, in an economy unrecovered from the crash of 2008: $500 a person for a set but unpredictable meal, exclusive of wine service and tax. And even if you were willing to blow that kind of money on a blue-chip version of the traditional Japanese hot-pot cuisine, you also had to pass a credit check and not lose your nerve after two warnings, one from a reservationist and the other from a captain on the way to your table, about how pricey your indulgent dinner was going to be.

My wife, Johanna, and I had Shaboo, with its intimate fifty-two seats, all to ourselves, literally, except for a gallant staff of young women attendants, who helped us get the hang of pushing foie gras and other luxury oddments around in broth simmering over cool magnetic induction burners integrated into our table. We counted eight courses and many ingredients flown in at great cost from Japan. It may be that if we had been a couple of deeply experienced Japanese shabu-shabolators, this meal would have been some kind of pinnacle in our overcosseted gustatory lives. But as nonadepts at this form of mink-lined Zen cookery, we had a far finer time for far less liquidation of euroyen across the hall in the vast Aria lobby-atrium-casino at Sage.

Young McClain wasn’t trying for a Guinness record as the world’s priciest chef at Sage. But he may have deserved one for most eclectically attentive to high-end trends. Sage’s subfusc elegance served as an all-purpose foil for food that represented his personal version of dishes that were hot all around the gastrostratosphere. There was a delicious foie gras crème brulée, a triumph of unctuous texture plays. Also, a slow-cooked “farm” egg, Iberico pork, toffee pudding—and a lot of other then-voguish ideas—were executed with assurance and even originality.

But what made this voyage westward really worth it was Twist, Pierre Gagnaire’s bistro de luxe on the twenty-third floor of the discreet new Mandarin Oriental. I’d already eaten with mixed emotions at Gagnaire’s flagship restaurant in Paris some years before, finding its food amazingly intricate but a muddle in the mouth, like a failed finger painting by an overly ambitious schoolkid: all those carefully managed ingredients melted together without any unifying taste drama. So I wasn’t going to be an easy sell at Twist, despite its eagle’s view of the lights of Vegas (a rare glimpse of the rest of the city from hermetic CityCenter) and the knowing assistance of a sommelier I trusted all the more since I had spied her at lunch at the Beard Award–nominated Thai restaurant Lotus of Siam, an unglamorous mecca for Feinschmeckers with a renowned German wine list in a grotty mall north of the Strip.‖

Gagnaire hadn’t totally abandoned his take-no-prisoners style at Twist, but his superego had gained control over his id. The foie gras tasting (four separate preparations, including a terrine with dried figs and toasted ginger bread; a custard with green lentils and grilled zucchini; a seared cube with duck glaze and fruit marmalade; and a croquette with trevicchio puree), served on a rectangular plate divided into four compartments, visually organized your sensations, and added up to an awe-inspiring and analytic tribute to the most overused expensive ingredient of all.

Gagnaire had also turned into an American locavore (at least in the airborne sense imposed on any cook in the agriculture-deprived environs of Las Vegas), sourcing his never-confined veal in Wisconsin from the estimable Strauss company. And to show what a great French cook can do with American lobster, Twist offered it poached in Sauternes with an impressive entourage of garnishes and a lobster bisque.

It was Gagnaire and Robuchon’s ability to adapt themselves to such an un-French, uniquely American setting that made their outposts in Nevada so special. If they had merely duplicated their brand of French luxury food in Las Vegas, that would have come off as sterile and smug, the way Alain Ducasse’s first restaurant in New York did. But Gagnaire and Robuchon were able to reinvent themselves in the desert. They weren’t cloning themselves, or conducting some stuffy mission civilisatrice among the heathen, as I felt Guy Savoy, another top Parisian chef, was doing at his restaurant down Las Vegas Boulevard, at Caesars Palace.

But even at their spectacular best, Robuchon and Gagnaire were pulling off a stunt. Las Vegas was not only not their home base, it was not, with the exception perhaps of a few native-born gastronomes, any of their customers’ home bases either. The big gamblers the casinos call whales, the splurging conventioneers, the food lovers like me—we fly in for a few nights and don’t come back for months or years. The pervasive mood of transience this creates is not the normal atmosphere that has historically nurtured great restaurants. Repeat customers, a sense of place, of rootedness—these are the missing ingredients in the epicure’s paradise of Las Vegas.

But they are the core strengths of the ambitious restaurants I kept dropping in at in almost every American town I wrote about over those four years at the end of the first decade of the new millennium.

Behind the molecular-gastronomic smoke and mirrors at Alinea in Chicago was a backdrop of midwestern rootedness. Grant Achatz learned to cook at a family restaurant on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, in Chicago’s hinterland. He established himself first at Trio in Evanston, a Chicago suburb. Charlie Trotter is a Chicago native who lives down the street from his venerable restaurant, which was situated in a town house before Trotter closed it in 2012. For many customers, Trotter’s was a neighborhood eating place, a very good neighborhood place. The Morgan Stanley financier Ray Harris ate at Trotter’s more than three hundred times.

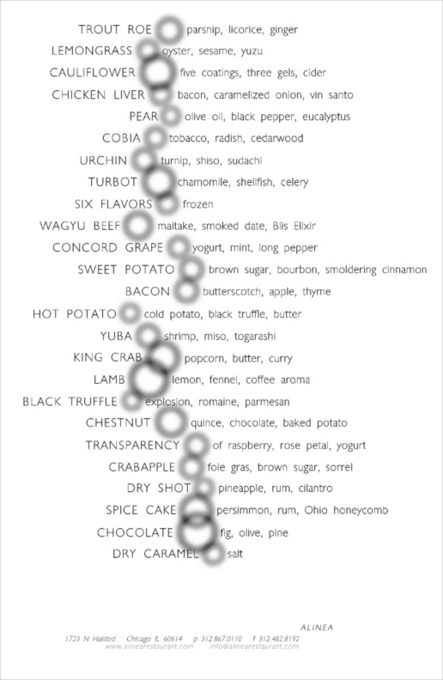

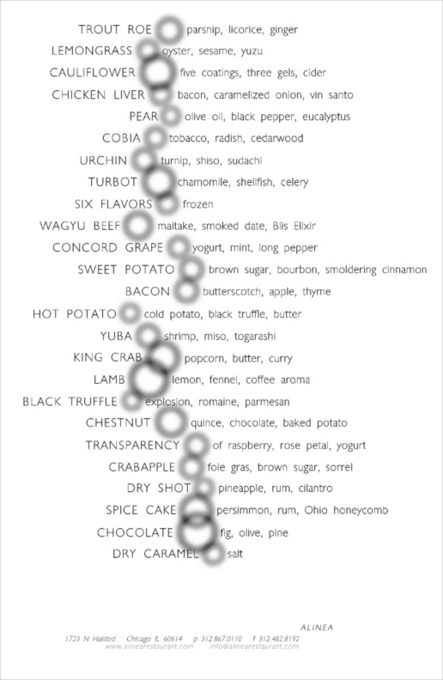

For a larger version of this menu, click here.

My dinner with Joel (and Maria) at Grant Achatz’s modernist Alinea in Chicago in early February 2007 included a helpful waiter who stood by to explain this cryptic menu. (illustration credit 5.2)

Most other cities in this era have restaurants with deep local roots that serve food of “national” quality. “National,” as I took to using it in Journal reviews, meant that a restaurant in Des Moines or Richmond, Virginia, was on a level with the best and most up-to-date dining places on either coast, or in other acknowledged food centers such as Chicago or Miami. And as I traveled around America, I learned, with gratification and diminishing surprise, just how many national places there were.

Take Sanford in Milwaukee. Like Charlie Trotter’s, it was established in a house, in a residential neighborhood, but the neighborhood was nothing fancy; neither was the little house where Sanford D’Amato and his wife, Angie, transformed a family grocery store into a soberly elegant dining room more than twenty years ago. Combining a cosmopolitan and up-to-date technique with local ingredients, D’Amato applied his French technique acquired at the Culinary Institute of America to roots cooking. When I ate there in 2009, I ordered a timbale of smoked salmon with rye cake, mustard mousseline and dill-pickled rutabaga. This was high-low cuisine, with humble ingredients and flavors you might have found in Milwaukee’s most vernacular saloons.

But there was nothing plebeian about Sanford’s menu, which featured “green”a Strauss veal gently raised twenty miles to the southwest in Franklin, Wisconsin. The night I was at Sanford, this pampered meat appeared as a sous vide–tamed “17-hour” veal breast with escarole and pickled hedgehog mushrooms in a burnt-orange reduction. I finished the meal with a plate of five Wisconsin cheeses. Snow White goat cheddar and Carr Valley Billy Blue were far from the run-of-the-industrial-barn cheeses Wisconsin sells by the carload to the outside world.

You could hardly ask for a more harmonious blend of sauce making evolved from classic principles, local sourcing of ingredients and modernist methodology. The humble cut of veal breast illustrated perfectly why the sous vide technique has spread far and wide. Really just a precise form of low-temperature cooking in a water bath, sous vide softens tougher cuts of meat without the aggressive force of a traditional, high-temperature braise. It can also cook a salmon without drying it out, leaving the texture as smooth and as flavorful as sashimi but not raw.

Sous vide literally means “in a vacuum.” The name has unnecessarily emphasized the fact that food is put in plastic bags, which then have the air sucked out of them, so that they cling tightly, protecting the food from the water in the bath but allowing essentially direct contact with the temperature of the water. Temperatures much lower than those of normal cooking preserved a freshness of flavor in the veal.

Later in 2008, I continued my heartland odyssey in Denver and Minneapolis, the two cities that hosted the party conventions, and made dining recommendations to the delegates.

I felt compelled to mention Denver’s taxidermic showplace for regionally farmed game (elk and yak), the Buckhorn Exchange. But the “national” choice here was Restaurant Kevin Taylor in the chic Hotel Teatro, down the street from the convention center in downtown Denver’s cultural and entertainment hub. I admired Taylor’s treatments of red meat, the contrasting textures of tender Colorado dry-aged lamb sirloin and melting lamb belly dressed up with twice-baked eggplant, figs and pimenton peppers; the counterpoint of locally farmed bison sirloin and barbecued back ribs with black beans, cheddar corn grits and charred tomatillos; and the Snake River Farms Kobe rib eye and beef-cheek two-step, with tasty potatoes and a truffle-accented béarnaise sauce. But I really liked his olive oil–poached halibut cheek—big enough to make you hope he hadn’t thrown away the rest of the fish. (Potato-crusted Alaskan halibut was available as a main course.)

At the other end of the social and sensory scale was Snooze, on a seedy block of pawnshops in Denver’s ballpark neighborhood, a breakfast place serving coffee specially grown for it at a Guatemalan finca.

Minneapolis wasn’t a patch on Denver, foodwise. The most original dining choice in the Twin Cities was on a drab block in plain-faced St. Paul, where I did my best to encourage Republican delegates to take their wives. If any of them did follow my advice and eat at Heartland, I am sure their power act didn’t faze my waitress, who brought eight wineglasses at one swoop to a table near me in the storefront establishment’s restrained dining room, with its open kitchen and rack of burly aluminum stockpots suspended above.

Heartland was locavorous on steroids, and I mean that kindly. Its Wisconsin elk tartare was a rich, dense, meticulously hand-chopped and not-at-all-gamy way to begin a splendid meal. I liked the menu so much I had a second starter: a subtly contrasting salad of chilled Canadian wheat berries and sweet corn with Donnay Dairy chèvre, microgreens and watercress pesto vinaigrette. I followed it with the midwestern mixed grill of Illinois fallow venison and Minnesota wild boar sausage, with Footjoy Farm flat beans, house-cured wild boar guanciale (jowl) and fresh ginger glace de viande.

Heartland was tucked away in a gray corner of the upper Midwest but cooking its heart out with top modern technique and bonhomie. As jumbo jets bound to shinier destinations flew overhead, the new food gospel was being preached here with expert ardor. Heartland literally inspired me, launched me on a long summer of exploration of flyover country to prove that savvy national places to eat abounded next to cornfields and in cities scorned by folks in New York County obsessed with snagging rezzies at Babbo.

In Omaha, bypassing Warren Buffett’s local haunt Gorat’s, where he washes down T-bones with Cherry Coke, I honed in on the rehabbed Old Market center, redolent of handmade soaps and other New Age gifts often found near fern bars. But in and around the exposed brick emporia were a couple of national-level watering holes, one hip and dreamy, La Buvette, the other, V. Mertz, tony and pricey, but smart, too. Both of them were the godchildren of a local boy named Mark Mercer, who had made sure that the Beef State no longer lacked places to consume foie gras poached in Sauternes or mallard breasts bedecked with a medley of fig, green bean, arugula, orange and pattypan squash.

And in Des Moines, I located another true believer at Bistro Montage. Enosh Kelly, the chef-owner at this small, intense neighborhood restaurant, was a national figure in his field and deserved the reputation he was getting, with nominations for best chef in the Midwest at the 2009 Beard Awards and kudos from other bellwethers.

There were plenty of tricky first courses on his menu—a salade niçoise with “house-canned” ahi tuna and Foxhollow quail eggs with a caper, egg and truffle vinaigrette, for example. But I was in a locavore mood and opted for the farmers’ market tomato salad, a mosaic of heirloom tomatoes as many-colored as Joseph’s coat, dotted with tangy white flecks of local goat cheese set atop some mild arugula.

From this celebration of the Iowa terroir, I moved on to “liver and onions,” a clever turn on the homely dish that usually bears that name. Kelly’s liver—an organic local calf’s liver, of course—was crisp on the outside, very pink within, cut in triangles and placed on a circular thin cake of grated potato, the great Swiss dish rösti. And Kelly didn’t forget the onions. They were the caramelized solid matter in the dark brown sauce.

Like the other nice midwesterners in the little dining room, I cleaned my plate and ordered dessert. With no fanfare at all, the menu offered marjolaine, the trademark dessert of Fernand Point, godfather of all things nouvelle. Marjolaine is a pastry chef’s spectacular, with thin layers of nut-embellished meringue and butter cream. On the way out, I glanced at a shelf of cookbooks, heavy tomes by contemporary world-beaters, including Thomas Keller and Heston Blumenthal. Kelly was keeping the wide world in his sights, from the banks of the Des Moines River.