IF THERE’S A PERSON OUT THERE WHO HAS A MORE compelling résumé—not to mention beard—than Indiana Jones, it’s probably Dr. Patrick McGovern. As the scientific director at the University of Pennsylvania’s Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory, he not only travels the world uncovering ancient treasures, he uses science to re-create the drinks those ancient people got tipsy on. By performing chemical analysis on the various potshards and containers that the expeditions find buried, “Dr. Pat,” as he’s known to friends and fans, brings extinct alcoholic beverages back to life after thousands of years. In one of his most impressive feats of Jurassic Park–ing a cold one, he even helped re-create a drink based on 2,700-year-old artifacts found in King Midas’s tomb, a honeyed nectar marketed as “Midas Touch.” Which, in and of itself, was a pretty compelling reason to get in touch. But when I found out that he’d collaborated with Sam Calagione at the Delaware-based Dogfish Head Brewery to re-create a form of Incan corn beer as well, my curiosity was piqued. And when I learned that this chicha beer was actually created using a pre-Columbian method of chewing the corn so that salivary enzymes would turn the starches into sugar . . . well, let’s just say I had to learn more. After all, how often do you see brewers chewing up and spitting out their grain before firing up the kettles?

Unfortunately, I was a little late to the party. The Chicha is only released in very limited quantities at the Dogfish Head brewpub and was not on tap at the time of my inquest (although I did find out that Dr. Pat’s Chateau Jiahu collaboration with the brewery, based on an ancient Chinese recipe, might be in stock and paired wonderfully with most Asian cuisine). But it wasn’t all for naught. I learned from Dr. Pat that indigenous beer was not unique to the Andes; Native Americans used fermentable sugars and wild yeasts to create a wide variety of beverages in many different places, including the modern-day American Southwest. Maíz, saguaro sap, perhaps even cacao would have all figured in the drinking habits of the first Americans to inhabit the area. An intriguing prospect for a regional beer historian, to say the least.

And the reason I currently find myself at the Arizona Wilderness Brewing Co., in a strip mall on the outskirts of Phoenix on a one-hundred-and-three-degree day. My brother, who lives in Phoenix, had first told me about the brand back when it was ranked number one among new breweries in 2013 by RateBeer.com. And now, at last, I had a reason to come to Arizona and give it a try. Well, fine, my wife, who is not American, also wanted to see the Grand Canyon. But as any beer lover can attest, it’s never a bad idea to sneak a little beer tasting into the itinerary. And while the expert brewers at the Arizona Wilderness Brewing Co. might not have any indigenous southwestern corn chicha on the menu for me to try, they do manage to accomplish some pretty amazing things with local ingredients—ingredients that very easily could have figured into Native American brews as well. In the past, they have offered beers made with everything from Sonoran white berries—a nearly extinct native grain used by Apaches in the Chiricahua Mountains—to a black IPA dry-hopped with juniper berries from the Juniper Mesa Wilderness. They’ve even gone so far as to brew with wild yeasts collected at 9,000 feet, in the mountains north of Flagstaff.

Today, however, it’s a session IPA that features mesquite pods picked from trees directly behind the brewery—no, it doesn’t get much more local than that. And if there’s anything more refreshing than the air-conditioning pouring in through the vents on this hot Arizona afternoon, it’s this beer. It is nothing short of delicious, full of floral notes, with just a slight citrusy tang. As to whether the mesquite pods are the secret ingredient in this magical concoction, I can’t really say, but it’s tasty regardless—and beats shopping for decorative Kokopelli garden motifs, even with my wife. The perfect combination, I would surmise, between indigenous ingredients and European brewing techniques, coexisting on the cusp of—just as the name suggests—the Arizona wilderness.

Innovative beers like this show the two distinct brewing traditions that came to exist alongside each other in the western United States. Now, I’m not saying Geronimo would have been sipping mesquite pod IPAs while some rough approximation of a hipster asked him if he’d like a second order of green chili pulled-pork sliders. But the brewing of alcoholic beverages did play an indispensable role to many of the Native American and European American inhabitants who came to call the western portions of the United States home. The former utilized it in their most sacred and life-affirming ceremonies, and the latter, as a cornerstone of a saloon culture that would come to define the western experience.

Two distinct legacies of regional American beer, alive and well and definitely commingling in a sunbaked strip mall on the outskirts of Phoenix. Not a bad way to start a chapter—or a hot summer day—in the heart of what still very much feels like America’s western frontier. Past the parking lots, the saguaros are undulating drowsily in the heat waves; to the east, the Superstition Mountains are catching the full brunt of the sun; and according to the message I just received, my wife will be looking at Kokopellis for another whole hour yet.

So, yes, I think I will have that second round of green chili pulled-pork sliders, thank you very much. And another one of these good mesquite pod beers while you’re at it, pardner.

One of the greatest myths perpetuated by Eurocentric history textbooks is that Native American civilizations did not possess the knowledge or technology to produce alcohol. We’re told that intoxicating beverages were introduced by the more “civilized” Europeans who strode in doffing their caps and toasting with fine wines. But this is categorically untrue. The panoply of alcoholic beverages consumed by indigenous Americans prior to the arrival of Columbus is frankly mind-blowing. In fact, one of ol’ Christopher’s first observations upon arriving in coastal Venezuela was the fact that the inhabitants drank two distinct alcoholic beverages, one from maíz, and another from maguey. True, they did not distill alcohol, just as Europeans did not before the Middle Ages. And alcoholic beverages did generally play less of a role in parts of North America where tobacco and hallucinogenic plants were the intoxicants of choice. But expert brewers and vintners were to be found in the Americas prior to the arrival of Europeans, alongside sprawling indigenous cities that dwarfed almost anything in Europe, and vast Native American empires that rivaled even Rome.*

The Mayans had their balché, a drink brewed from tree bark and wild honey. The Indians of what is now British Guiana preferred paiwari, a beer made from chewed cassava. The Jíbaros of Ecuador consumed a manioc beer to celebrate when the head of an enemy was taken in combat, a sacred yucca beer fermented in earthenware jugs, and a sweet wine produced from the fruit of the chonta palm—a robust drink list, to say the least. The Matacos, Chorotis, and Ashluslay all made algoroba beer, and across Mexico, Nahuatl-speaking people enjoyed then, just as they do today, the delights of pulque, a fermented drink made from the agave plant. The inhabitants of Guatemala’s Pacific coast even savored, much to the surprise of early Spanish explorers, a drink made from cacao pods, “an abundant liquor of the smoothest taste, between sour and sweet, which is of the most refreshing coolness.” Evidently, long before Europeans “discovered” chocolate and turned it into candy bars, Native Americans had already perfected a delicious chocolate liqueur. And that’s just the beginning—the list of indigenous beverages goes on and on, including everything from the maple drinks of the Iroquois, to the persimmon wines of the Cherokee. Hog plums, custard apples, pineapples, cashews, wild grapes, sweet potatoes, wild bananas, elderberries, pepper trees, and yes, even mesquite pods . . . if it had starch or sugar in it, someone, somewhere, probably fermented it.

But if there was one drink that stood above all—one that was consumed from the southern peaks of the Andes, straight up to the edge of the Great Plains—it was corn beer. The very chicha that Dr. Pat re-created using an ancient recipe for Dogfish Head’s Ancient Ales series, and that is still made using traditional methods by many modern-day indigenous peoples. Corn was truly the native grain, first domesticated from the wild teosinte plant in Mexico’s Balsa River Valley around seven or eight thousand years ago. Some archaeological theories suggest that it was actually a thirst for a corn-based wine made from maíz stalks that helped propagate the plant beyond its native region. Either way, whether it was for corn drinks or corn meal, by 1500 B.C., corn-based agriculture had spread well beyond Mesoamerica. At some point, when corn had become just domesticated enough to produce soft, chewable kernels, corn beer came into the picture. The process of mastication didn’t just crush the kernels; it added salivary enzymes that began the process of converting starches into sugar. Essentially, it was an alternative to malting—a way of making a starchy staple more palatable to wild yeasts. And after what was no doubt a considerable amount of chewing and spitting, the first beer in America was born.

Native Americans were expert brewers of a vast assortment of intoxicating beverages and incorporated them into many of their most sacred ceremonies. Some beverages had hallucinogenic and, in a few instances, even emetic properties.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

The process of making and drinking corn beer was generally ritualized and carefully controlled in most indigenous societies. In an interesting analog to the English alewife, women did much of the brewing. According to early Spanish observers, the Incan rulers of Peru selected a group of beautiful girls to be mamakona—essentially beer nuns—who remained chaste and brewed exclusively for the palace. Chewing the corn before spitting it into a collection vessel was a sacred activity to be accompanied by songs and incantations. Once fermented, consumption of the beer was equally regimented. Among the Incas, it was customary for the king to pour chicha into a golden bowl, part of “the navel of the universe,” as a way of slaking the Sun God’s thirst. They even rubbed corn beer on sacrificial victims and force-fed them through tubes while they were buried alive in ceremonial tombs to intoxicate them for the big event. And the most notorious human sacrificers of all, the Aztecs of central Mexico, were equally fond of chicha and also incorporated it into their rituals. In some cases, a bit too fond, as draconian rules were put into place to control the usage of the intoxicant. With a powerful drink known as the “bone breaker” made from toasted corn, stalk juice, and pepper tree seeds, ready to knock anyone who consumed it right off their feet, it isn’t terribly hard to imagine why. To combat wanton intoxication, the Aztec Codex Ixtlilxochitl recommended the following rather severe punishments for inebriation outside of the temple:

Thus the drunkard, if he was plebian, had his hair cut publicly in the market square, and his house was sacked and torn down, because the law said that he who deprived himself of his good judgment was not worthy to have a house but could live in the fields like an animal; and the second time he was punished with death; and if he was noble the first time that he was caught committing this crime he was punished with death.

“Heavily regulated,” however, does not necessarily mean “consumed in moderation.” Corn beer, and other intoxicants, served a religious purpose: they were a source of visions and altered states, and a means of direct communion with the gods. And when ceremonies mandated, alcohol was consumed in massive quantities. The rain dance tradition of the Tohono O’odham people of the Sonoran Desert demonstrates how sacred rituals and overindulgence could go hand in hand. “Much liquor we made,” one woman of the tribe remembered, “and we drank it to pull down the clouds.” Upon burying the beverages for fermentation, women would chant, “Do you ferment and let us get beautifully drunk.” Once that fermentation was complete, it was considered customary to drink a neighbor’s alcohol until vomiting ensued, and then to continue drinking at a different neighbor’s house after that. It was nothing short of a sacred duty, and a means of strengthening the community and ensuring a bountiful harvest.* Such bouts of overindulgence were periodic, though, conducted as part of a larger ceremonial calendar—drunkenness was not a part of everyday life, and a host of taboos and regulations existed to protect celebrants and make sure it did not become one.

Corn beer also traveled north from Mexico, into what today is considered the Southwest and western portions of the United States. It wasn’t the only alcoholic beverage consumed—a form of pulque called “tulpi” was drunk by some southwestern groups, a saguaro wine was preferred by the Maricopa and Pima of the Sonora, and in California, various tribes were recorded as making a strong cider from manzanita berries. But corn beer, or tiswin, as it was known to the Apache, was the predominant beverage in what would become Arizona and New Mexico. Unlike older forms of corn beer, tiswin was made from sprouted corn that had been dried and ground—that is to say, malted. Beyond that, recipes varied wildly according to tribal and regional preferences. Various ingredients were added to the frothy, pale-colored corn beer, to accentuate its natural sweetness and to enhance its effects, and fasting often took place before it was consumed so that the alcohol would pack more of a punch. Tiswin on its own was not very high in alcohol, and as one Apache would later remember, “It was not much stronger than water—took a lot to make you drunk.” The Natty Light of the ancient world, you might even say. But it was popular, and when available, Apaches did consume it in ample quantities, because it was not very difficult to make. An Apache woman named Dahteste, who was with Geronimo in the rebellion days of 1886, shared her recipe:

Chicha, a type of indigenous corn beer, was consumed in many parts of North and South America. Ritual drinking cups like this one were used throughout the Incan Empire.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

To make tiswin you grind corn fine on metate. Build a big fire, boil meal twenty minutes. Take it out, squeeze mash out good. Throw grounds away. Put in jar and let ferment with yeast twenty-four hours. It took much longer when we had no yeast.

In fact, it was tiswin that was largely responsible for Geronimo’s decision to leave the reservation and return to the traditional lands of his people—on the reservation, Apaches were prohibited by the occupying U.S. military from brewing their sacred drink, or using it in traditional ceremonies. This ban was one insult among many that would eventually lead Geronimo and his followers into open rebellion against an uninvited and alien government. To men like Geronimo—and to many indigenous peoples across North and South America—native alcoholic beverages were not simply a refreshing drink or a welcome intoxicant. They were an essential part of their sacred cosmology, and one of the few direct conduits to the spiritual world. Whether it was called chicha, tiswin, pulque, or tulpi, such drinks were treated with ceremony, decorum, and great respect. And far from going extinct or being confined to a reservation, indigenous drinks and their distilled progeny continue to be consumed across the Americas to this day, both in their original forms, and in slightly altered states. When the indigenous ingredients met the European technique of distillation, entirely new forms of alcohol were created, drinks with distinctly American identities and flavor profiles that cut across cultural boundaries. After all, bourbon whiskey is little more than distilled corn beer that’s been aged in a barrel, and tequila, in all its tangy splendor, is simply a form of pulque that’s been passed through a still. An interesting note to end on, that two of our most popular and beloved spirits are the direct offspring of the fermented drinks of the very first Americans, and a natural segue into the arrival of European-style beverages to the western frontier.

The concept of “the West” in America has never been static. To colonial Anglo-Americans on the Eastern Seaboard, it constituted the edge of the Appalachian Mountains. In the first decades of America’s independence, it came to mean the lands that lay just beyond them. Beginning with the expedition of Lewis and Clark in 1804, and continuing throughout the nineteenth century, though, the West increasingly came to mean the territories that could be found beyond the Mississippi. And with Manifest Destiny all the rage, and Americans convinced that a nation spanning two oceans was within their reach, settling those lands and subjugating their native inhabitants became a top and rather tragic priority. They weren’t the first colonizers to settle in the West—the French territory of Louisiana had theoretically included most of the Great Plains, and thanks to early forays made by the Spanish, most of California and the Southwest were nominally part of Mexico. The colonial presence in the western half of North America had been relatively weak, though, with the French and Spanish focusing most of their attention on the more profitable plantation colonies of the Caribbean and Latin America. This part of the continent that was unknown to most Europeans was a tempting prospect for immigrants who had come to America searching for what they could not find at home: a piece of land to call their own. Just as Scots-Irish pioneers had escaped the seaboard to homestead the Appalachian wilderness, and just as German Americans had left New York and Philadelphia to set up shop in the Middle West, a fresh batch of hopeful Americans from a wide variety of backgrounds began packing their bags and loading up the covered wagons in the middle years of the nineteenth century.

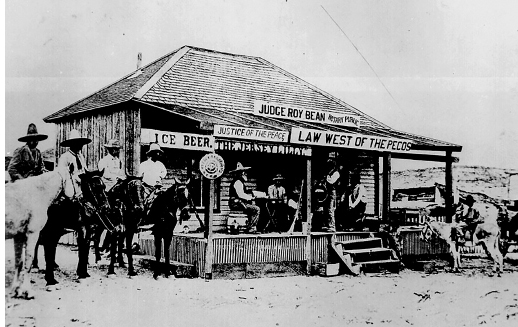

In the Southwest, elements of both European and Native American brewing often coexisted in close proximity. In this photo, a saloon in Arizona displays indigenous motifs.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

And they brought plenty of alcohol with them, although for the very first settlers, this seldom meant beer. Going west entailed carrying whiskey—it was an essential, practically a form of currency in a place where paper money didn’t do anyone much good. Even the Lewis and Clark expedition had brought six kegs of the hard stuff with them, only to run out by Great Falls. In part, this preference for whiskey was shaped by the same geographic factors that made it prevalent in the mountain South: it was nonperishable and easily transportable in a region with few roads and widely dispersed settlements. But there were economic considerations as well. Whiskey not only appreciated in value the more time it spent in the barrel—its value also increased exponentially the farther away it was sold from eastern civilization. In the 1830s, a barrel of low-quality whiskey could be purchased in St. Louis for as little as 25 cents. By the time it reached Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, that same barrel might sell for 34 dollars, and by Yellowstone, well, a business-savvy settler could value that cheap barrel of whiskey at as much as 64 dollars. The whiskey could then be traded for much-needed supplies, used to procure the assistance of an experienced guide, or, as was often the case, simply kept for personal use. Not surprisingly, because of the high values placed on early frontier whiskey, the quality plummeted. Whiskey peddlers sold watered-down and adulterated “barrel whiskey” to pioneers, and oftentimes an even fouler concoction to Native Americans, who had little experience with stronger spirits and were exploited in the cruelest of ways. The initial crop of western saloons that sprang up at dusty frontier outposts were crude, whiskey-selling establishments—forget refrigeration and carbonation. With wagon trains and stagecoaches taking months to cross the plains, getting a bulky barrel of beer to the West was at best impractical and, at worst, flat-out impossible. Whiskey was the obvious choice.

Until the train came along, that is. The same technological innovations that had allowed the dizzying growth of midwestern breweries in the second half of the nineteenth century also brought beer to America’s westernmost outposts. By 1869, the first transcontinental railroad had already spanned the coasts and made western rail shipping possible. And refrigerated railcars changed the game entirely. When coupled with regional icehouses, not to mention the more shelf-stable pasteurized bottles that would come later, beer became an everyday commodity. By 1876, grocers and saloons in Denver, Colorado, were already advertising Anheuser-Busch’s “St. Louis Lager Beer.” By 1884, the company had thirteen agencies in Texas alone, all storing, cooling, and distributing Budweiser beer for the thirsty inhabitants of the Lone Star State. The competing St. Louis firm of William J. Lemp had branch offices in such far-flung cities as Leadville, El Paso, Wichita, and even Salt Lake City. And when the Jos. Schlitz Brewing Co. brought suit against the Southern Pacific Railway regarding what they saw as unreasonable shipping rates and unfair practices, many of the more powerful brewers decided to forgo the crooked rail barons entirely and began buying trains of their own. Anheuser-Busch played a significant part in the establishment of the Manufacturers Railway Company, and Joseph Uihlein, a major figure in Schlitz management, was the true owner of the Union Refrigerator Transit Corporation. With time, the gargantuan breweries of America’s heartland made significant inroads into its westernmost fringes.

But not all westerners were content to wait around on the next beer shipment, or to be totally reliant on brewers back east. Indeed, small local breweries had been making beer since before the railroads. And even after they came along, railways didn’t extend to every western town, and packaged beer didn’t always survive the long journey in peak condition. One very early example of regional western brewing comes courtesy of the first German settlers of San Antonio, who arrived in Texas in 1844 under the leadership of Carl Prince of Solms-Braunfels, just prior to annexation. Back in Germany, or even back east, for that matter, a weary farmer could retire “after his evening meal and a glass of beer or wine, [and] go upstairs to his room and stretch his tired limbs on a bed, even though it be only a mattress of straw.” In Texas, though, Prince Carl noted, “there is no strengthening drink of beer or wine on the table whereby he could refresh himself.” Even after beer did finally arrive on the scene, it was anything but accessible. He would write to prospective newcomers to his little German colony: “The only thing that is really expensive is wine, beer, and any kind of alcoholic drinks. The beer is imported from the United States, and is very strong. One called this kind of beer ale. I do not think it can be kept in good condition during summer.” Evidently, these early Texans not only had to put up with outrageous prices, but extra-strong import-grade ale from the East, a far cry from the cool, crisp lagers they preferred.

According to the billboard, railroads and Pabst beer were two of the nation’s greatest achievements. That may be debatable, but the former did bring the latter to the American West.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Such hardships, though, were not to last. Prince Carl eventually hung up his cowboy hat and returned to Germany, but many of his fellow settlers stayed. And by 1855, a delicious lager beer—or at the very least, a lager yeast beer, if it was not cold-conditioned—was being produced by a brewer and cooper named William A. Menger. His brewery was so successful, he also built a hotel to accommodate drunken visitors, and he began delivering his stock all across the state in wagons and oxcarts. Menger would pave the way for Lone Star beer, originally brewed by the Alamo Brewing Company of San Antonio in 1874 and later acquired by Anheuser-Busch, not to mention the Spoetzl Brewery, founded near the town of Shiner in 1909. The latter produced then, just as it does today, a Shiner bock beer—a darker, maltier style of Bavarian lager that was largely eclipsed by paler lagers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Both Lone Star and Shiner are still beloved by Texans, something akin to the “national” beers of a people who have never forgotten—nor miss a chance to remind you—that the Lone Star State was once, however briefly, an independent republic.

Although whiskey kept better in frontier conditions, beer wasn’t far behind once a new western settlement became established. Trains brought both beer and ice to thirsty cowboys and miners.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Texas led the pack when it came to western brewing, but other territories were quick to catch up. When silver was discovered in Nevada, breweries weren’t far behind the prospectors—at least twenty-one breweries could be found in the territory by 1871, scattered across towns like Eureka and Carson City. In the supposedly abstemious Mormon lands of Utah, eager settlers not only produced a crude whiskey called “Valley Tan,” but also beer. By 1884, the territory of Utah could claim some eighteen breweries to its name, with three in Salt Lake City alone. The Idaho Territory had four breweries to wash down its spuds, the Montana Territory had no fewer than three breweries in Virginia City and four in Helena, and Arizona, although it lagged behind its competition, did make gains once malt was made available from San Francisco via the railroads. So much so, that in 1885, the city of Phoenix was actually able to make an entire sidewalk with discarded beer bottles. The streets of the frontier town may not have been paved with gold, as many eager migrants had hoped, but they were paved with beer.

Even Judge Roy Bean’s joint advertised “Ice Beer” to parched Texans. This photograph shows a horse thief being tried on the front porch of the saloon.

Breweries sprang up in large numbers across the western frontier, but the progress the beer industry made in the deserts and plains would be dwarfed by the rise of mountain brewing in Colorado, and with good reason: the high elevations meant lower temperatures and an ample supply of ice, both of which made lager brewing considerably easier at a time when refrigeration was either expensive or lacking altogether. The Gold Rush of 1857 and 1858 brought wagonloads of miners into Colorado, and just as in other territories, beer came along for the ride. In fact, a large brewery was up and running in the town of Auraria in just one year. It was an early attempt at mountain brewing, and some ingredients weren’t easy to come by—one drinker remembered that “though quite drinkable, [it] was as innocent of hops as our early whiskey was of wheat or old rye”—but it was a start. By 1861, a larger, more professional establishment called the Tivoli Brewing Co. was already brewing bock beer in Denver, and the towns of Laporte and Boulder had sizable breweries by 1862 and 1875, respectively.

Then Adolph Coors came to town. Born in Germany, like many western brewers, Adolph had been a brewer’s apprentice in Dortmund and later worked at breweries in Berlin and Kassel. After coming to America, he hopscotched around the German neighborhoods of New York and Chicago, only to discover that both the East and the Midwest were already saturated with German American breweries. The West, on the other hand, was still wide open and considered fair game. So in 1872, he relocated to Denver and established a bottling business, which proved to be a nice stepping-stone to opening his own brewery the very next year, in a town called Golden, just a few miles outside of Denver. Using a pilsner-style beer recipe purchased from a Czech immigrant, he and his partner, Jacob Schueler, began making their crisp, pale lager. By the 1880s, their brewery was already one of the largest and best equipped of the twenty-three breweries in the Rocky Mountains. Just like that, the high-altitude ancestor of “the Silver Bullet” was born—destined to produce one of the most popular beers in the American West, and to one day become the largest single brewery facility in the world.

The advent of canned beer and home refrigeration would one day turn beer drinking into a domestic activity—but those days were still a long ways away on the western frontier of the late nineteenth century. The hardscrabble assortment of cowboys, ranchers, farmers, and miners drank beer not in the home, but in the saloon. Just as the English-style tavern had become the center of town life in New England, and the German-derived beer garden a mainstay of midwestern culture, the western saloon managed to serve as town hall, political society, gambling parlor, dance hall, courthouse, and social club, all at the same time. As a saloon was oftentimes one of the few reliably populated public structures in a western town, it was only natural that much of the settlement’s social life would occur inside its batwing doors. Kentucky bourbon, which the railroads had made available west of the Mississippi, was always a favorite, as were an elaborate array of western cocktails.* But the combined supplies of local brews and imported labels from the East meant that once a town and a railroad were both firmly established, there were usually buckets of beer to be had by all. At the infamous Long Branch Saloon in Dodge City, Anheuser-Busch was on tap, kept cold in the summer by ice shipped in from the mountains of Colorado. A saloon owned by George Brown in Big Spring, Texas, only served beer, with customers using kegs as stools and drawing nickel drafts from ice-cold barrels. When natural ice wasn’t available, beer was often kept cool in nearby streams, or simply served at room temperature—at least, until artificial refrigeration came into the picture. In most cases, the saloon was one of the few places a tired westerner could relax among friends, and sometimes enjoy a cold drink.

The saloon may have been heralded as a great achievement by the thirsty cowhands, ranchers, and miners who flocked to enjoy the liquid comforts of its polished bar, but it gained its fair share of detractors as well. Between 1850 and 1890, the population of the United States increased fourfold; its consumption of beer, however, grew twenty-four-fold, from 36 million gallons to 855 million gallons. Saloons also grew in number, from some 100,000 in 1870, to 300,000 by 1900. And it doesn’t take a genius to tell that the two numbers were related, and closely at that. Some of the beer did simply replace whiskey, a beverage that had fallen comparatively out of favor due to the meteoric rise of German lager. But the explosion of immigrant-owned breweries had spurred a dramatic upsurge in immigrant-owned saloons as well. And while saloons were prevalent in the immigrant neighborhoods of eastern cities like New York and Boston, the relative isolation of western towns and the skewed ratios of rowdy young men to women certainly made the western saloon among the most visible—and notorious. In Leadville, South Dakota, a town with a population of 20,000, there was one saloon for every 100 inhabitants—women and children included—and similar ratios were to be found in towns across the West. Some of these establishments were no doubt pleasant, clean, and upstanding places. But just as many were replete with “the stench of stale beer and whiskey often mixed with the nauseating smell of vomit on the sidewalks,” as one visitor to a western town noticed. And it was certainly no secret that the bulk of these saloons had direct ties to major German American–owned breweries. After all, men like Gustave Pabst and Adolphus Busch had spent a fortune bankrolling saloons across the West and plastering then with every Custer painting and branded piece of schwag they could come up with. German names like theirs were everywhere. Then, of course, there were also all those gunfights and beer brawls.

To many Americans—particularly those of British Protestant backgrounds and nativist leanings—the stability of their country seemed to be under threat, thanks to a rising tide of ethnic newcomers. Of course, this was total hogwash. The idea of an original “American” people was flawed from the start. As even a cursory study of American history (or a scan of the first few chapters of this book) would have shown, the country had been a diverse melting pot from the get-go: a place where Dutchmen and Dominicans could trade rounds on the streets of New Amsterdam, English aristocrats might pick up techniques to make molasses beers from more experienced West Africans, and Scots-Irish settlers could master a new whiskey grain with a little help from the Cherokee. Hardly the homogenous land of teetotalers that the emerging temperance movement imagined. But the privileged economic role many Anglo-Americans had enjoyed began to feel precarious, and “foreign” elements made a convenient scapegoat. By the first decade of the twentieth century, native-born Americans were increasingly demanding a national ban on the saloons and the drinks that they served. Drunkenness was seen as a scourge brought by immigrants, rather than the reality of American life it had always been—the Pilgrims, after all, were not drinking Kool-Aid, and George Washington was hardly one to toast with Tang.

The temperance movement didn’t begin in the West—Maine had been at the vanguard of an earlier prohibition push that banned alcohol completely in the state in 1851, and Chicago had even experienced a “lager beer riot” in 1855, when German and Irish immigrants reacted violently to a series of new antisaloon legislation. But the unique circumstances and emerging regional politics of the West certainly added a tremendous dose of fuel to the flames and brought local antialcohol legislation at the state and county level long before it became the law of the land. The Progressive movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries took on a life of its own west of the Mississippi, and while its aims were both high and admirable, it had a darker side as well. Yes, it did promote equality and women’s suffrage—a number of western states had given women the vote well before the 1920 passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. But it also gave birth to the hatchet-swinging harridan known as Carrie Nation, whose respect for private property stopped at the very saloon doors she hacked to pieces. It did increase the regulation of mining, railroad, and ranching interests that were growing wildly out of control, in a part of the country where government oversight had been weak. Yet it also allowed populist hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan to control local governments across the Rockies and the Northwest. Reform was all the rage, but increasingly, it came to mean driving out all that was deemed foreign and un-American in the name of bettering this new, “progressive” society.

Unfortunately for America, alcohol was to take the brunt of the blow. Suffragettes, Klansmen, Progressives, and Populists from around the country may not have agreed on much, but for once, they all seemed to find common ground in their dislike of drinking and drinking establishments. With the spoken aim of protecting the American family, and the unspoken goal of disempowering immigrants and Catholics, for whom saloons and the production of alcohol were often cultural staples, the crusade against booze began, under the leadership of the Anti-Saloon League. As an ominous precursor to what was to come, Congress passed the Sixteenth Amendment in 1916, establishing a national income tax to make up for the loss of government alcohol revenues that were not far in the offing. The next year, when the 65th Congress convened, “dries” already outnumbered “wets” by 140 to 64 in the Democratic Party, and 138 to 62 in the Republican Party. And with the declaration of war against Germany that April, the formerly vociferous heads of German American breweries suddenly found it best to keep their mouths shut—anti-German sentiment had reached a fevered pitch, and zealots like Wayne Wheeler of the Anti-Saloon League were actively calling out the “alien enemies” who controlled such household names as Pabst and Anheuser-Busch. When the Eighteenth Amendment was finally ratified, and Prohibition became official, it almost felt redundant, especially in the West, where most states had already been dry for several years. On January 16, 1920, the Volstead Act went into effect, and across the country, an industry that had helped nourish a nation and power a people for nearly three centuries ground to a halt. The unthinkable had occurred: beer was, to the dismay of its brewers and much of the public, completely verboten.

It was somewhat ironic that the American West—a region where life centered on the saloon—also produced many of Prohibition’s earliest champions. Even before the Volstead Act went into effect, most western states were already dry.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

But wouldn’t you know—people didn’t stop drinking. Not by a long shot. The mild-mannered, law-abiding, churchgoing era that the Anti-Saloon League and its promoters envisioned turned out to be fantasty, and the “noble experiment” proved to have some rather ignoble results. Bootlegging flourished, organized crime took control of the wheel, and in the speakeasies and blind tigers that sprang up all over America, the Jazz Age was born. Culturally, America was flourishing, as writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald, musicians like Louis Armstrong, and singers like Ella Fitzgerald combined their voices to make the 1920s roar. And the country’s drinking habits were more scandalous and decadent than ever, as a young generation of Americans came to realize they didn’t want to sip a thimble-full of Grandma’s blackberry cordial—they wanted to get loaded.

And so they did, with the drinking culture of the day aimed at the ultimate goal of inebriation. The government had deemed alcohol a powerful intoxicant rather than something to be savored, and the nation’s youth took that to heart. Cocktails became standard fare in urban speakeasies for the same reason they had first been popular in western saloons: they helped disguise the taste of cheap, poorly made spirits. And poorly made, these spirits were. People mostly drank bathtub gin and low-grade moonshine whiskey, with illicit rum from the Caribbean and blended scotch from Canada available for those who could pay. In either case, the spirits were contraband, which meant that low volume and high potency were key. It was far easier to smuggle a bottle of spirits across state lines than a keg of beer, and that bottle of spirits could stay on the speakeasy shelf almost indefinitely. Beer was simply too bulky, too low in alcohol, and too hard to mix with anything else. For people who just wanted to get hammered on the sly, a rich, thirst-quenching, high-volume product made no sense. The drinkers of America turned their attention away from their beer steins and became besotted instead with a martini glass of the hard stuff.

With the arrival of Prohibition, American drinking habits literally changed overnight. What had been a cultural staple suddenly became a controlled substance. In this photograph, 749 cases of illegal beer are being destroyed.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

But beer lovers are a notoriously stubborn—and nostalgic—lot. And there were more than a few who weren’t going to go down without a fight. Some smaller breweries were able to stay under the radar; Al Capone controlled no fewer than six breweries in the Chicago area alone, all of which continued to produce beer in the shadow of the Volstead Act. Larger, more prominent breweries couldn’t risk flouting the rules so publicly, but they did offer a range of suspicious malted syrups that, although ostensibly used for baking, could quite easily be put into service by a resourceful home brewer. And then there was the infamous “needle beer.” As breweries struggled to stay afloat, many continued to brew nonalcoholic beer for the general public. And it didn’t take the general public long to figure out that just a squirt of grain alcohol from a syringe could turn a mug of legal nonalcoholic beer into something that had at least a passing resemblance to the full-bodied brews they had known from before. Unfortunately, the resemblance was precisely that: passing. Although initial sales of nonalcoholic beers marketed under names like Bevo and Manna looked promising—300,000,000 gallons were produced in 1921 alone—the enthusiasm didn’t last. By 1932, that number had dropped to 85,000,000 gallons, as America’s boozehounds came around to the fact that they’d rather drink real moonshine than fake beer. But the production of such nonalcoholic beers did offer at least some source of income to the country’s harried brewers.

In most cases, though, malted syrups and needle beer were not enough to keep a brewery in business. Prohibition was a disaster for the American brewing industry, wreaking havoc in a way unseen before or since. Leaders like New York’s Jacob Ruppert used their positions in the USBA to lobby on the industry’s behalf, pleading with the government to allow the production of low-alcohol “near beer” at the very least. But their protests were in vain, and breweries had to find creative ways to keep from going under. Some, like Anheuser-Busch and Yuengling, capitalized on their existing fleet of refrigerated trucks to sell ice cream. Schlitz, Miller, and Pabst turned their attention to cheese, chocolate, and other confections. And soft drinks were produced on a scale that would change America’s palate forever, with ginger ale and root beer being made by chagrined brewmasters, to supply the soda fountains that had replaced taverns as social centers. Some resorted to fruit juices, breakfast cereals, and yeast extracts, others to animal feed, vinegar, and industrial alcohol—desperate breweries were willing to try just about anything.

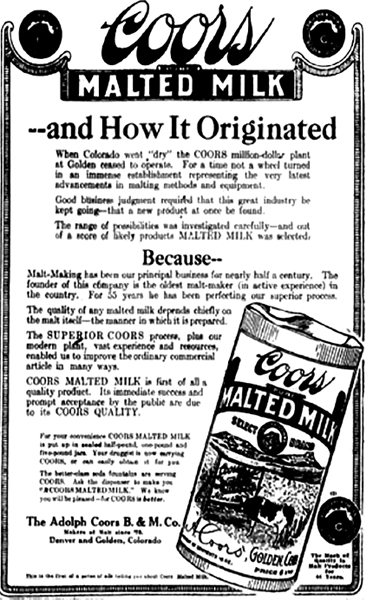

In the West, however, one brewery in particular would emerge looking golden: Coors. Adolph, the founding father of the venture, along with his sons Adolph Jr., Herman, and Grover, had possessed the foresight to diversify the business well before the Volstead Act effectively shut down their beer-making capacity. The manufacturing wing of his company devoted itself to porcelain—a version of which still exists today—while the construction wing dealt in cement and real estate during an era in which construction was booming across the West. Its brewing facilities, meanwhile, focused on the sale of malted milk—much of it going to the Mars candy company, to be used in the variety of chocolate bars that were replacing cold beers as the standard after-work treat. When Prohibition finally ended, when the din subsided and the smoke cleared, the handful of large, resourceful breweries like Coors that had managed to weather the thirteen-year storm were virtually all that remained of the nation’s beer makers. The stage was set and the market was ready: the age of the American macrobrew was about to begin.

It’s easy to poke fun at the mass-produced American beer labels that have formed the bulk of our nation’s brewing industry for very nearly a century—they’re an easy target. And while even the snootiest of beer connoisseurs may still enjoy a macrobrew nostalgically at a ball game or ironically at a dive bar, it’s no great secret that many contemporary drinkers turn up their noses at the same quotidian can of suds their parents and grandparents savored. Perhaps with good reason. After all, compared to the darker, richer, more character-driven beers that existed in America before Prohibition, and when put alongside the traditional European ales and lagers that never went out of style in the first place, the American macrobrew can indeed be a disappointment. The malt is generally weak and one-dimensional, the hops are usually bland and lacking in aromatics, and the drinker is often left feeling overcarbonated and underwhelmed. But before we judge such beers too harshly, we should consider where they came from in the first place. The pale lager of the twentieth century was born directly out of calamity and desperation, and all of us—brewers, consumers, and everyday citizens—helped bring it into existence. We as a nation collectively made it so.

To survive Prohibition, breweries with the resources often switched to making nonalcoholic products. This advertisement extols the virtues of Coors Malted Milk. The smaller breweries that could not adapt generally went under.

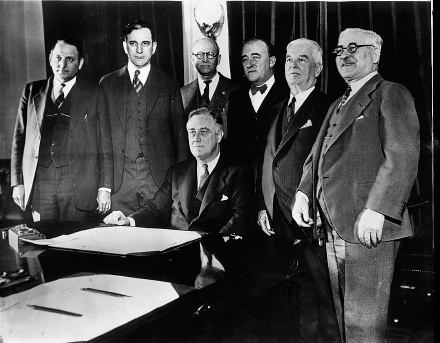

Prohibition was finally repealed in 1933, not because of an intellectual epiphany or cultural awakening, but because of the greatest economic disaster America had ever faced. In the wake of the stock market crash of 1929, the country’s economy was in free fall—the Great Depression had begun, and suddenly the United States Treasury was desperate for cash. In the past, taxes on alcohol had supplied the federal government with up to 40 percent of its revenue, and with banks closing and stocks plummeting, it finally occurred to the bright minds in Washington that perhaps shutting down the brewing and distilling infrastructure of America had not been such a good idea after all. In just a few short years, they went from hunting down illegal brewmasters and smashing their barrels, to all but begging them to get the brew kettles fired up and working again.

With only one small problem: there were hardly any American breweries left. Of the 1,392 breweries that had existed prior to Prohibition, a measly 164 remained by its end to supply America’s beer—a tall order, any way you look at it. And those that did survive the turmoil were for the most part in dire financial straits. Thirteen years without being able to sell beer had taken their toll—the pressing issue wasn’t necessarily about a return to the high standards of before, but of simple survival. Keeping the American beer industry alive inevitably meant cutting corners, and many brewers quite understandably did what they could to get back on their feet quickly. All in the midst of the Great Depression, no less, a time when many were struggling to eat, let alone drink.

As for consumers, the years of Prohibition also had a lasting effect. An entire generation of drinkers had come of age at a time when beer was essentially nonexistent, and sugary cocktails and soft drinks were all the rage. Alcohol during the Roaring Twenties wasn’t supposed to be well-made or full of complex flavors—it was simply expected to be easy to swallow and to get you drunk. The collective memory of the hoppy, rich, Bavarian-style lagers that had existed before Prohibition was replaced instead by a thirst for anything cold, bubbly, and cloyingly sweet. American tastes had changed. Somewhere down in the glittering world of the speakeasy, we’d learned to drink watered-down cocktails and forgotten how to drink well-made beer.

From these circumstances emerged the American macrobrew: a sweeter, more watery, and less flavorful version of the original American pale lager that had slowly evolved in the decades after the Civil War. With the hobbled breweries struggling to make a profit again, and Americans with stunted taste buds happy to drink a beer that was simply alcoholic, nobody was complaining. To an impoverished industry and a weary public, it was enough to have the beer taps flowing again. Cheaper and more sweet-tasting adjuncts like corn were used in greater proportions than ever, original high-gravity recipes were diluted to stretch the barley supply even further, lagering times were frequently cut in half, and in some cases, even a hop extract replaced the zesty and complex bouquet of actual hops. Americans across the board wanted a cheap, easy-drinking beer, and that was exactly what we got.

President Franklin Roosevelt signing “the Beer Bill” in 1933, effectively bringing Prohibition to a close. Brewers were ecstatic, but they still had considerable work ahead of them to get back on their feet.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Even so, convincing Americans to become beer drinkers again took time. Prior to 1914, per capita annual consumption had been roughly 21 gallons—a hefty average. By 1933, that number had plunged to less than 9 gallons a year. In the year that followed Prohibition’s repeal, just over 20 million barrels were taxed by the federal government—significantly less than the 60 million barrels that had regularly been taxed in the years before the Volstead Act came into effect. Cocktails, soft drinks, and good ol’-fashioned milk all competed with beer. But by cutting production costs, and by capitalizing on advancements in bottling technology—home refrigeration was becoming commonplace, and pasteurized bottled beer generally lasted longer than draught—the recovering breweries were able to make up for lost time. The introduction of the first canned beer in 1935 by the Krueger Brewing Co. of Newark further reduced costs and shelf life and improved the beverage’s domestic appeal. Pabst Export Beer followed in its footsteps, and soon, cheaper canned beer was being adopted by breweries and drinkers across the land. An article from the trade publication Modern Brewery Age sums it all up quite nicely:

A western beer brand celebrates the end of Prohibition with an advert urging retailers to put in their new orders. They assure customers it’s “the same fine beverage,” although with the Great Depression and World War II looming, it is a promise that will prove difficult to keep.

Those who prefer to drink their beer in taverns will always find that source open to them. But [with] this new form of merchandizing—whether it is “canned beer” or the “stubby bottle”—reaching the low income homes and bringing in its development increased beer consumption . . . should be encouraged in every possible way.

More and more, beer was being drunk in the home, and breweries began focusing their attention on home consumers. Brewers were initially uneasy at the thought of advertising in the years after Prohibition, with a host of local antialcohol regulations still in place and the fear of the ban still fresh in their memories. But that reticence didn’t last long, as the obvious benefits of advertising for attracting a new breed of domestic consumer quickly became clear. At a tavern or saloon, a beer drinker’s options were limited to whatever the barkeep had on tap—and given the practice of brewery sponsorships, that selection was usually not very robust. At the store, on the other hand, the consumer could take his or her pick from an array of beer brands. All at once, it was of the utmost importance to convince that consumer that one specific brand of beer trumped all the rest—an ironic claim, given that American beer had become more uniform and lacking in individuality than ever. Anything stronger and more distinct was simply unsalable, possessing, as one nostalgic beer drinker would note, “just too much hop for this generation.” But alas, such was the expertise of Madison Avenue.

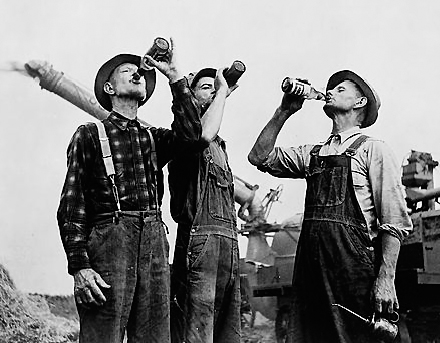

It wasn’t easy to convince Americans to start drinking beer again after Prohibition, but by the 1940s, we had become once again a nation of beer lovers.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

And it worked. It took time, but the measures slowly kicked in. By 1940, sales of beer were roughly what they had been before Prohibition—a feat accomplished with less than half as many breweries. Through rampant consolidation and growth, the industry had become dominated by a handful of brewing powerhouses, most of which are familiar to the American beer drinker today. That same year, Anheuser-Busch, Pabst, Schlitz, Schaefer, Ballantine, and Ruppert were all producing over a million barrels a year, with Anheuser-Busch number one with over two million. And if there were any voices in the industry suggesting a return to pre-Prohibition lager, with its richer malts and more robust flavors, they were quickly silenced by the outbreak of war. As the United States found itself drawn into the tumult of World War II, the government recognized beer as the inherent morale booster that it was. If Uncle Sam was going to ask G.I.s to dodge bullets and bombs in the farthest corners of the globe, the least he could do was give them a cold one. The nation’s brewers saw the opportunity and responded enthusiastically, citing beer’s naturally high vitamin B content as an additional incentive. Accordingly, the government bought beer in bulk, requesting 15 percent of total production for servicemen, an order that boosted the industry tremendously, but also cut into the nation’s rationed grain supply, as noted by this New York Times article from August 1, 1943:

In March the WPB said that malt was needed to make alcohol for munition; that brewers must cut their use of it 7 per cent under the 1942 figures. To make up the deficiency, brewers turned to corn and rice. Now breweries are feeling the pinch of the nation-wide corn shortage . . .

As one might expect, the brewers did what they had to do to fill the orders, upping the adjuncts and diluting the flavor of American beer even further. But who was going to complain? Not a hardworking American public, which was making sacrifices galore to help with the war effort, and certainly not servicemen, who were a long way from home and preparing to make the ultimate sacrifice of them all. Any American beer was greatly appreciated, for the taste of home that it truly was, as indicated by this recorded conversation between a commanding officer and a mess sergeant, featured in Modern Brewery Age:

COMMANDING OFFICER: Do I understand that the water you get here is unsafe?

MESS SERGEANT: Yes, sir.

COMMANDING OFFICER: What precaution do you take to ensure the health of the outfit?

MESS SERGEANT: We filter the water first, sir.

COMMANDING OFFICER: Yes.

MESS SERGEANT: Then we boil it.

COMMANDING OFFICER: Yes?

MESS SERGEANT: Then we add chemicals to it.

COMMANDING OFFICER: Yes.

MESS SERGEANT: And, then, sir, we drink beer.

In helping to save the free world, brewers also saved their own industry. During the war years of the 1940s, production of beer grew by over 40 percent, eventually exceeding pre-Prohibition levels. And the demands of greater production in many cases meant expansion to new territory—a problem that large breweries solved by buying out smaller, more distant breweries, or simply by building new regional franchise breweries that produced the same beer.

In World War II, thirsty servicemen helped bring the American beer industry back to life—the government put in huge orders to keep the troops stocked. The injection of capital got breweries going full steam again, but due to grain rationing, the flavor profile of American beer became generally less malty and complex.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

By the 1950s, though, with the war won and the nation thriving, finding new beer markets increasingly meant going west. Not the mining towns or cattle stops that breweries had alighted upon a century before, but the far West: the burgeoning cities and suburbs of California, a state whose population had exploded during and immediately after the war. In 1953, the Theo Hamm Brewing Co. bought out the Rainier brewery in San Francisco. In 1954, Anheuser-Busch built a brewery in Los Angeles for the then unthinkable sum of $20,000,000, while Pabst took over another Los Angeles brewery to make sure its Blue Ribbon beer was available as well. And as for Schlitz, that same year, it built a brand-new plant in Van Nuys, California, that could on its own turn out a million barrels a year. But cans and bottles, mind you, not barrels, were the name of the game. This was the blossoming of the atomic age, a period of suburban homes and automobiles, of microwaves and TV dinners. American consumers didn’t want old-timey products and carefully crafted goods—they wanted cheap and convenient, uniform and reliable, shiny and new. And after decades of corporate consolidation and mechanized mass production, the canned beers that sat in our fridges were exactly that. A far cry from the handcrafted Dutch ales, dark English porters, and complex German lagers that our predecessors had enjoyed, but precisely what we, as a people exhausted by all those years of prohibition, depression, and war, were after. We weren’t interested in going downtown to some ethnic saloon, to sing old folk songs and sip at a stein of malty lager. We just wanted to finish mowing the lawn, turn on the tube, and crack open a cold one. Progress—or so we thought.

But something must have changed, no? Or how else could it come to pass that here, in the twenty-first century, a man might sit in a suburban strip mall outside of Phoenix, Arizona, enjoying one of the most deliciously complex session IPAs he has ever tasted in his life, with nary a can of macrobrew in sight?

Indeed, something did change, and to find its origins, we’ll have to go a bit farther west yet. The big beer conglomerates may have driven most of the traditional California breweries out of business, but a couple of throwbacks just barely managed to slip through the cracks—one of which was destined to change the course of American beer in the most unexpected of ways.

So get ready. That craft beer revolution we’ve been all been waiting for is about to begin, with its earliest champions to be found not in any venerable eastern city, but rather on our country’s westernmost and grooviest coast.

(Cue the Beach Boys.)