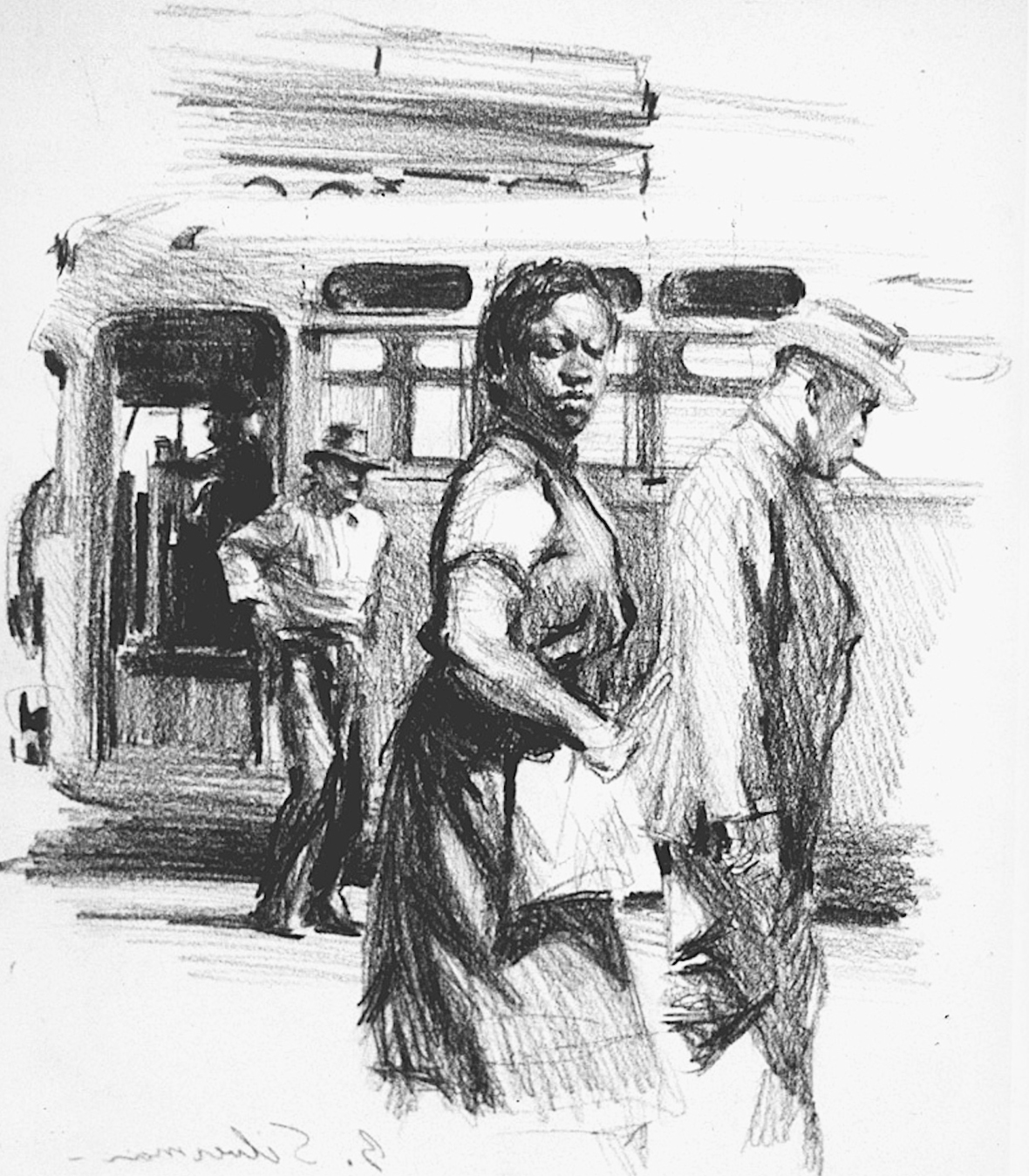

Montgomery Bus Boycott, by Burton Silverman. African Americans, predominantly working class, ended bus segregation in Montgomery, Alabama, after 381 days of nonviolent economic withdrawal.

“We the Disinherited of This Land”

Kinship with the Poor, 1929–1956

Let us continue to hope, work, and pray that in the future we will live to see a warless world, a better distribution of wealth, and a brotherhood that transcends race or color. This is the gospel that I will preach to the world.

—KING TO CORETTA SCOTT, 1952

IN 1967, AT A BAPTIST CHURCH IN CHICAGO CALLED MT. Pisgah, Martin Luther King, Jr., commented, “It is the black man who to a large extent produced the wealth of this nation . . . the black man made America wealthy.” Although some talked of going back to Africa, he said, “I’m not going anywhere. . . . My grandfather and my great-grandfather did too much to build this nation for me to be talking about getting away from it.” When he preached, King drew upon knowledge of the slave ancestors and sharecroppers from whom he was less than two generations removed. This history may be unknown to many whites, but it provided a basic framework for King. We typically remember him as a well-dressed, seemingly middle-class proponent of the “American dream,” but in fact he came from African American and Irish dirt-poor people who lived the American nightmare.

At union conventions and in churches King continually linked slavery as part of an exploitative economic and racial system that needed fundamental transformation. “Segregation is wrong because it is nothing but a new form of slavery covered up with certain niceties of complexity,” he told a union convention on September 8, 1962. The sermons and spirituals he grew up with linked King back to centuries of striving and to ancestors he never met.

Willis Williams, King’s great-grandfather (b. 1810) lived as a slave for over fifty years in Greene County, Georgia, seventy miles east of Atlanta. In theory, he gained his freedom on January 1, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in the Civil War the North was losing. Lincoln’s enlistment of black soldiers and the withdrawal of labor by slaves helped bring down the Confederacy. The day after the proclamation, Willis’s partner Lucrecia (Creecy) gave birth to Martin’s maternal grandfather, Adam Daniel Williams. Slaves on the other side of King’s family tree included Martin’s paternal grandfather, Jim Long (b. 1842), used by his owner to “breed” other slaves. The history of King’s ancestors had a basic labor component: slavery more than any other system of production used labor exploitation to make some people rich.

Along with the theft of Native American lands, the exploited labor of millions of slaves served as a basic building block of white wealth. Karl Marx aptly called slavery, along with piracy and the stealing of peasant and Native American lands, sources of the “primitive accumulation” of capital. Unpaid black labor fueled the rise of slaveholders in the South and the profits of mercantile and banking capitalists in the North, who invested in the slave trade and in cotton, which before the Civil War became America’s major export to the world economy. Most slaves at the bottom of this economy of racial capitalism worked without wages and had no control over their labor, their families, or their conditions of life. Indentured servants and poor whites suffered similarly but were not consigned to poverty for life by their skin color. In places like Memphis, Tennessee, the largest slave-trading depot between Cairo, Illinois, and New Orleans, Louisiana, whites rationalized an evolving system of cheap labor by creating a hierarchy of “races,” with European whites at the top and African Americans, Indians, Asians, and Mexican Americans at the bottom. We now know that all humans are part of the same species originating in Africa, but racial ideology and markers throughout history have provided powerful ways to separate people into competing groups. As anthropologist Ashley Montague documented, the false idea of race is “man’s most dangerous myth.”

For workers, racism had devastating effects, undermining any notion of labor solidarity. White supremacy laws and practices separated workers and farmers by skin color, making interracial marriages illegal and even requiring nonslaveholding whites to serve in slave patrols to capture escaped slaves. As W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in Black Reconstruction, dividing poor and working-class people called “white” from people called “black” made it very difficult to organize labor in the South or anywhere else. The “wages of whiteness” provided some perceived and some real advantages, but the labor of most workers designated as “white” accumulated capital for someone other than themselves. During his Poor People’s Campaign in 1968, King repeatedly referred to the horrors of slavery to explain the origins of the black freedom movement and its demands for economic justice. Africans did not come to the United States looking for a better life, as one conservative later ludicrously claimed; rather, slave traders stole a better life from them. Slaves went on a “general strike” and over 200,000 African Americans joined Union Army regiments that helped to win the Civil War, yet one hundred years later, King would have to fight for civil rights and economic justice to redress the nation’s failure to bring full freedom.

Sometime after the Civil War, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s great-grandfather James Albert King moved to Georgia from Pennsylvania hoping to obtain land and economic independence. The son of an Irish father and an African American mother, he married Delia Long, and the couple had ten children. The second of them, Martin’s father Michael, was born in 1897. It was one year after the Supreme Court supported the fiction of “separate but equal” as the law of the land in Plessy v. Ferguson. Ex-Confederate states by the end of the century, through voter-suppression laws and violent white-supremacy campaigns, wiped out black elected officials and the right to vote. White-supremacy campaigns repeatedly destroyed biracial struggles for greater economic justice by workers and farmers in unions, Populist, and “fusion” movements.

Instead of gaining economic independence, as the King family hoped, they became sharecroppers, working on land owned by whites. They earned only a small share of the crops they produced, while going into debt to landowners and merchants for food, seed, and fertilizer. Women lived lives of hard labor, and Martin’s grandmother Delia worked for white folks washing and ironing. James moved from place to place working for crops and wages in Henry and Clay counties. Indebtedness, phony “vagrancy” arrests, imprisonment, and convict leasing plagued black women and men alike. Segregation, or Jim Crow, made it illegal for blacks to share the same restaurants, transportation, schools, or public facilities as whites. They could not sit on juries, hold office or vote, and were consigned to schools that received little public funding. Most whites sought to keep African Americans out of skilled labor, to hold down their wages, to limit black property holding, and to block access to trade unions and education. Driving too nice a vehicle, owning too good a mule or too much land, failing to step off the sidewalk when a white person came the other way—in the era of segregation, these and other supposed transgressions against white supremacy could get a black person killed.

This system of Jim Crow capitalism suppressed the economic aspirations of King’s ancestors. Born December 19, 1899, in Stockbridge, Georgia, Michael King, Martin’s father, experienced deep poverty in the countryside, where, in his words, an African American “wasn’t nothin’ but a nigger, a workhorse” denied formal training as a worker or a chance to learn to read and write. As an adolescent, he witnessed the dangers of walking while black. He saw a mob of white men taunting a black man, who tried smiling, turning his back and walking faster, pretending normality. The whites beat him bloody and then lynched him with his own belt. Michael later wrote that such white violence happened because white politicians constantly stirred “the passions of all potential voters by appealing to their sense of insecurity.” Southern white politicians made a profession of distracting whites from their poor economic conditions by egging them on to racial violence. Neither the lynching of black men falsely charged with rape of white women or for insolence, nor the actual rape of black women, met with legal consequences. Black women and men could end up not only imprisoned but also forced to work under horrendous conditions on chain gangs, with their labor sold to private landowners or coal companies. Black women especially suffered from white sexual exploitation with no consequences for perpetrators.

In these perilous conditions, in another incident, a white mill owner beat young Michael bloody in front of a crowd of white men when he refused to drop a can of milk he was carrying for his mother and instead fetch water for him. When she found out about it, Michael’s enraged mother knocked the white man down; in a separate incident, Michael’s father James threatened the man with a gun. A mob of white vigilantes soon came after James, who escaped to the swamps. He returned home after several months of hiding out, despondent and alcoholic. Michael had to physically fight with his father to stop him from beating his mother. Rebellion with no hopes of success dragged the family down.

Martin’s father went to a one-room school for only three to five months a year, where a lone black woman taught children in all grades, with no books or blackboards. He spent most of his time doing farm work for pennies an hour. In 1918, functionally illiterate, Michael left the rural district of Stockbridge, Georgia, and hiked to Atlanta, wearing his only pair of shoes and with nothing but ambition in his pockets. His dear mother died and he lost track of his father. He worked in a tire shop, loaded cotton, drove trucks, and did odd jobs. He seemed condemned to a working-class life of poverty, but religion, deeply inculcated in Michael by his mother, provided joy and inspiration. Michael preached and sang the gospel, and it saved him.

Martin’s maternal grandfather, A. D. Williams, was born into slavery at the start of the Civil War in 1861, in Greene County, Georgia. During the 1880s he followed his father’s struggle to be a preacher but experienced poverty in the countryside, working in low-wage jobs and losing his thumb in a sawmill accident. In 1893 he got to Atlanta with five dollars in his pocket. Like his slave father, Willis Williams, A. D. preached the gospel as a way to imagine something beyond the South’s nightmare regime of labor and racial exploitation. In 1894, A. D. became the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist church, a congregation of former slaves with thirteen members. A. D. built the congregation that built the church that still stands in Atlanta. He attended Atlanta Baptist College (later named Morehouse), and on October 29, 1899, married former Spelman Seminary student Jennie C. Parks, whose father was a carpenter. They had one surviving child, Alberta Williams, born September 13, 1903. This was Martin King’s mother.

For more than thirty years, A. D. and Jennie made Ebenezer a rock in a weary land for urban and working-class African Americans. The black church, Cornel West wrote, provided the only institution “created, sustained, and controlled by black people.” Sermons, songs and congregational meetings built a sense of community and the ability “to come to terms with death, with dread, with despair.” Ebenezer’s members survived a five-day white race riot in 1906 that left twenty-six black people in Atlanta dead. The King family and others fought back nonviolently, pressing for black schools, voting and legal rights, and jobs. Martin Luther King, Jr., would later receive his education in elementary and high schools that his grandfather helped to create with public funding through protest. He would also inherit his grandfather’s and his father’s commitment to the working class and poor. Ebenezer Baptist Church took care of poor families, orphans, and the ill, baptized and buried people, raised money for schools and civic institutions, and nurtured a sense of hope that kept people’s spirits alive.

Martin’s great-grandfather Willis Williams had been a Baptist exhorter as a slave, and every generation after that used Christianity to resist Jim Crow’s hardships and humiliations with a religion of hope. Through the black church, Martin King, Jr., would learn, West explained, to relate his expansive ideas “to common, ordinary people and to remain ensconced and enmeshed in their world.” And he would learn “such values as integrity, love, care, sacrifice, sincerity, and humility. . . .”

Through the church, the Williams and King families joined forces. Young Michael weighed over two hundred pounds, but at age twenty-one squeezed into a small desk in a class with fifth graders to learn to read and write. He married Alberta Williams, daughter of Jennie Parks and A. D. Williams, who convinced Morehouse College president John Hope to let Michael into its school of religion, from which he graduated. Alberta also got degrees from Spelman Seminary and Hampton Institute, and she and Michael married on Thanksgiving Day, 1926. In 1931, upon the death of Rev. Williams, Michael King took over leadership of Ebenezer Baptist Church. His family and his people in the church largely consisted of former slaves and sharecroppers, many of whom now worked as laborers and domestic workers. Rev. King put the concern of these poor and working-class people at the core of his ministry.

Historian Clayborne Carson identifies the King family ministry as part of a black Christian Social Gospel that “combined a belief in personal salvation with the need to apply the teachings of Jesus to the daily problems of their black congregations.” Protestant reformers in the United States, in churches, immigrant settlement houses, and civic and labor reform organizations, undertook the Social Gospel tradition in the late nineteenth century in response to the evils of unregulated capitalism—gross inequities between the rich and poor, suppression of worker rights to unionize, mass slums for immigrants and workers, unemployment, prostitution, and destitution. The black church evolved its own version of the Social Gospel in response to both racism and economic injustice.

Michael King and his son would both take the gospel of Jesus as told to Luke (Luke 4:18) as their guide. Jesus told Luke to “preach the gospel to the poor,” “to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives,” and “to set liberty those who are oppressed.” Martin would say that the commandments of Jesus required society to not only help the poor, but to change the conditions that made them poor.

* * *

ON JANUARY 15, 1929, Michael King, Jr. (later renamed Martin Luther King, Jr., after his father changed his name to Martin Luther King, Sr.) was born, in a nicely built but modest home, surrounded by a largely poor neighborhood filled with shotgun shacks and poverty. Yet this district also consisted of the black churches and black-owned businesses for which Auburn Avenue would become famous. Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote in a 1950 college essay, “I have never experienced the feeling of not having the basic necessities of life.” Despite the fact that the Great Depression followed hard on the heels of his birth, he recalled, “The first twenty-five years of my life were very comfortable years. If I had a problem I could always call Daddy. Things were solved. Life had been wrapped up for me in a Christmas package.”

Yet the young Martin knew he had privileges others did not have. His father took him to see the unemployed standing in lines for food and taught him respect for the unemployed poor and working poor. “Daddy” King led campaigns and marched for black schools and teacher funding and voting rights. He disobeyed the rules of segregation, riding the “Whites only” elevator at city hall, refusing to step off the sidewalk to make way for whites, and resisting demeaning white attitudes. He taught his son by his own behavior. When a white police officer stopped the Kings in the car and referred to him as “boy,” Daddy King pointed to his son and shot back, “This is a boy. I’m a man, and until you call me one, I will not listen to you.”

Martin’s father also marched them out of a shoe store when a white clerk refused to seat them in the same area as whites. He told his son, “I don’t care how long I have to live with this system, I will never accept it.” When Daddy King changed his name and that of his son from Michael to Martin Luther, he signified larger aspirations to take on the world.

Martin’s mother Alberta King and his grandmother Jennie Williams also had a major impact on his personality and sense of the world. Martin’s female ancestors had labored hard in their own households and in the fields, and suffered from low wages from white employers, while nurturing hope and shaping the black Social Gospel. In the King home in Atlanta, his mother and grandmother provided a forgiving and nurturing environment of love, kindness, and spirituality. Grandmother Jennie, Martin wrote, had a “saintly” aura, and “it is quite easy for me to think of a God of love mainly because I grew up in a family where love was central and where lovely relationships were ever present.”

The power of the love that flowed so strongly from his mother and grandmother and the authority of his father engendered personality traits of compassion, kindness, and empathy that would make Martin King a special kind of leader. By contrast, the family of Malcolm Little (Malcolm X) was torn asunder by the Depression and poverty, by his father’s murder by white vigilantes and his mother’s incarceration in a mental institution. Racism and poverty destroyed many such families. Instead, Martin King developed an inspiring optimism born out of a supportive family environment and adopted the traditions of hope and struggle epitomized by church songs with lyrics such as “I’m so glad trouble don’t last always,” and “Keep your eyes on the prize, hold on.”

The young King grew up in an all-black neighborhood and went to an all-black school, somewhat protected from the ravages of white supremacy. But he knew he could not vote or hold office or even pass whites on the sidewalk without fear. A white playmate’s father no longer allowed him to be friends with his son; a white woman slapped him in the face in a shopping area for no reason; Martin witnessed a KKK beating of a black man; he passed sites where he knew blacks had been lynched. At age fourteen he won an oratorical contest in Dublin, Georgia, with his speech on equal rights, “The Negro and the Constitution,” but a white bus driver made Martin and his teacher give up their seats to white passengers and stand in the aisle for ninety miles riding back to Atlanta. “It was the angriest I have ever been in my life,” he recalled. In another incident, white conductors forced him behind a curtain in the rear of a segregated railroad dining car. “I felt as if the curtain had been dropped on my selfhood,” he wrote, and recalled thinking, “One of these days I’m going to put my body up there where my mind is.” He would easily see the logic of the Montgomery bus boycott.

In a college paper in 1950, King wrote, “The inseparable twin of racial injustice was economic injustice. Although I came from a home of economic security and relative comfort, I could never get out of my mind the economic insecurity of many of my playmates and the tragic poverty of those living around me.” He believed “the numerous people standing in bread lines” contributed to “my present anti-capitalistic feelings.” As a teenager in the 1940s, King worked briefly in a southern factory but quit when the foreman called him a “nigger.” In another summer on a tobacco farm in the North, “I saw economic injustice firsthand, and realized that the poor white was exploited just as much as the Negro.”

King’s associate and friend C. T. Vivian told me in an interview, “The whole relationship between blacks and labor was something that was everyday for any middle-class black person to understand.” One could always find poor people, white or black, barely surviving on low wages and sometimes no wages at all.

King’s education created a framework for understanding the inequalities he saw all around him. As a precocious student, at age fifteen Martin entered Morehouse College, where professors explained why black people were oppressed and most were poor, and taught him about his proud heritage as an African American. Morehouse president Dr. Benjamin Mays, a learned minister, educator, and author who met with and studied Gandhi, fused religion, academic knowledge, and activism on behalf of equal rights and social justice in weekly talks to Martin and other students. They studied sociology, history, philosophy, literature, and religion during World War II, a time when the NAACP launched a “double V for victory” campaign against fascism abroad and racism at home. By the time King left Morehouse, Vivian believed, he “already knew ninety percent” of what he needed to know in order to preach the black Social Gospel. He would do it better than anyone in the twentieth century.

As a bright and eclectic scholar at Crozier Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, from 1948 to 1951, and at Boston University, where he received his PhD in systematic theology in 1955, King studied history, literature, and theology in the Judeo-Christian tradition. He appreciated the writings of Reinhold Niebuhr, who highlighted the twin injustices of racial discrimination and the unequal distribution of wealth under capitalism. King paraphrased Niebuhr’s critique of Christianity, writing, “Any religion that professes to be concerned about the souls of men and is not concerned about the slums that damn them, the economic conditions that strangle them and the social conditions that cripple them is a spiritually moribund religion awaiting burial.” King’s philosophy stressed the importance of individual experience and one’s relationship to a personal God. He also drew upon the Hegelian dialectical method that allowed him to synthesize truth from seemingly conflicting ideas such as Marxism and capitalism to find a “third way” to economic justice. However, as scholars Clayborne Carson and Keith Miller both document, King’s powerful oratory came not from his academic studies but from the deep wellsprings of the African American church. Ordained as a preacher at Ebenezer Church at age eighteen, King from an early age drew heavily on the Exodus message of deliverance from slavery, the slave community’s most well-known Bible story. As his learning progressed, he appropriated the phrases and ideas of theologians, poets, philosophers, historians. Like a jazz, gospel, or blues musician, and like the most popular of Protestant preachers, he arranged texts to speak age-old truths.

In graduate school King heard black theologian Howard Thurman speak about his meeting with Mohandas Gandhi, and also encountered the twentieth century’s leading white pacifist, A. J. Muste. King added to his repertoire the idea that “nonviolent resistance was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their quest for social justice.” But he recalled that at first “I had merely an intellectual understanding.” King might have gone on to live a comfortable life. Instead, history led him into a life of struggle marked by his solidarity with working-class and poor people.

At Boston University King presented himself not as an activist but as the quintessential middle-class student: well dressed, well educated, with marvelous diction and a poetic use of the English language. He drove a new car and wore such nice suits that friends at Morehouse had called him “tweedy.” He lacked only one thing in his quest to become a top preacher: a wife. Then he met the vivacious Coretta Scott, a student at the New England Conservatory of Music. She lacked Martin’s family advantages. At age ten, she had picked two hundred pounds of cotton in a day for pennies per hour in rural Perry County, Alabama. The Scott family, with Irish, Native American, and African American ancestors, lived and worked on three hundred acres of land acquired as freed slaves after the Civil War. White vigilantes who thought the family was too prosperous burned down Coretta’s father’s sawmill and the family’s home burned down under suspicious circumstances as well. In another incident, white men hanged Coretta’s uncle from a tree outside his home and filled his corpse with bullets. Armed white men regularly confronted Coretta’s father Obadia when he hauled lumber to the mill, and he carried a loaded pistol in his open glove compartment to let them know he could not be intimidated.

Coretta had already committed herself to political and social action by the time she met Martin in college. During World War II, she went to Lincoln High School in nearby Marion, Alabama, a private school founded after the Civil War by freed slaves and white abolitionists. White teachers encouraged her, and a Quaker teacher brought Bayard Rustin to speak about Gandhi’s struggle against British imperialism through nonviolence. In 1945, when Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, recruited her as the school’s second black student (her sister was the first), she found her “escape route” out of the segregated South.

In 1948 Coretta attended the national convention of the Progressive Party (unknown to her, Martin attended as well). Former Democratic vice president Henry Wallace ran for president on a peace platform calling for détente with the Soviet Union. The mass media red-baited all Progressives as part of a “Communist front.” Howling mobs of whites attacked Wallace during his interracial speaking crusade through the South, accompanied by singers Paul Robeson and Pete Seeger. Even as the United States descended into Cold War anticommunism, before leaving undergraduate school Coretta sang on a program with Robeson. The U. S. congressional House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), formed in 1938 and led by segregationists, hounded him, and the red scare drove him into unemployment and obscurity. HUAC would hold scores of “hearings” falsely linking “communism,” labor, and civil rights from the 1940s through the 1960s.

Coretta Scott went north penniless and could stay in school at the New England Conservatory only with the help of white donors. Competing for the intellectual attention of this lovely young woman brought out Martin’s political side. At first she thought he seemed presumptuous, but she was quickly impressed by his strong opinions on racism, capitalism, and economic injustice. While they were apart during the summer in 1952, she sent him a copy of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, a classic utopian socialist novel published in 1888. In a letter to Coretta, King mixed his admiration of her beauty and intellect with an appeal to her political consciousness. He noted, “I am much more socialistic in my economic theory than capitalistic,” and surmised “capitalism has out-lived its usefulness. It has brought about a system that takes necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes.”

During King’s childhood, unprecedented uprisings by workers in industries and among the unemployed had led to President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, which ensured the right of workers to vote for a union of their choice and required employers to bargain with them in good faith. Employers resisted this in many places, but especially in the South. The old American Federation of Labor (AFL) was an amalgam of overwhelmingly white and male craft unions that typically barred blacks, other minorities, and women from apprenticeships and even from union membership. Yet some white southern unionists believed strongly in racial equality. Members of the Communist Party in particular made equal rights, advocacy for the legalization of interracial marriage, and bringing blacks and whites together the bedrock of their southern organizing. Not surprisingly, they experienced heavy repression.

In 1935, when Martin was six, United Mineworkers president John L. Lewis and a group of unions broke away from the AFL to form the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which took an unequivocal stand for racial equality. Black workers, consigned to the hottest, most dangerous jobs, came to play a key role in CIO advances in the steel, packinghouse, auto, and other industries. Communist and Socialist Party members and an assortment of anticapitalist radicals organized on behalf of racial equality and civil rights unionism—advocacy for labor and civil rights together. The Southern Tenant Farmers Union in the Southwest and the Sharecroppers’ Union in Alabama came under ferocious attack for doing so.

Through CIO industrial organizing, during World War II the American labor movement expanded dramatically and even made inroads into the South. It also began to break down racial barriers. In 1941 A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a black union, threatened a mass march on Washington demanding access to defense jobs. President Roosevelt issued an antidiscrimination executive order that helped remove racial barriers to industrial jobs, although it had few enforcement mechanisms. White reaction to black competition for jobs and housing precipitated the white race riot in Detroit in 1943, leading to the deaths of thirty-four people, twenty-five of them black, and the destruction of the black neighborhood called Paradise Alley. White reaction against black advances occurred in various other cities and workplaces.

Nonetheless, by 1944 millions of black and white workers, in the South as well as nationally, in AFL as well as CIO unions, had created a powerful labor movement. The basis for a civil rights–labor alliance existed: NAACP membership ballooned; the Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF) built an effective interracial popular front for unionization, ending segregation, and electing better people to office. Highlander Folk School, independently formed by Social Gospel activists in the hill country of Tennessee in 1932, allowed adults to discuss their problems and decide for themselves how to solve them, without political or racial restrictions. At the end of the war, the CIO and other organizations seemed ready to move the South toward higher wages, better conditions, and away from Jim Crow capitalism.

In 1946 American workers undertook the largest strike wave in U.S. history, based on pent-up demand for increased wages after wage restrictions during the war. The CIO also began “Operation Dixie,” an ambitious campaign to organize the millions of unorganized workers in the South. But in the 1946 congressional elections, voters put in place an overwhelmingly Republican Congress dead set against organized labor. It enacted the Taft-Hartley Act, an employer-drafted law weakening unions. Its provision 14(b) allowed states to ban a “closed shop,” whereby everyone covered by a union contract had to pay membership dues to the union for representing them. Within a year, seven of thirteen southern states passed “Right to work” laws that allowed workers to get union benefits without paying union dues—so of course many chose that option. Taft-Hartley made secondary boycotts and picketing by unions supporting each other illegal; it limited union political contributions; excluded foremen and supervisors from labor-law coverage; tied unions up with massive legal requirements; and required union officers to take a legal oath that they did not belong to the CP. If they did not sign, their union could not get on the ballot in National Labor Relations Board–protected elections. It killed much of the labor organizing in the South, as intended by its Republican sponsors. To make matters worse in the postwar years, black soldiers returning from fighting a war against Hitler’s white supremacy abroad found themselves subject to ugly hate crimes, racial discrimination, and lack of employment opportunities at home. The CIO’s southern organizing drive ran into internal racial and left-right political divisions, antiunion violence, and Taft-Hartley’s restrictions. Right-wing organizations, along with federal government “loyalty” oaths and investigations of “communism” in the body politic poisoned any discussion of unions and civil rights. Then, in 1948, the CIO leadership endorsed Harry Truman for president while many of the left-leaning unions endorsed Progressive Party peace- and civil-rights advocate Henry Wallace. After the surprise reelection of Truman, and in response to rising anticommunism, the CIO purged eleven left-led unions with nearly a million members, and CIO unions began competing to take over the memberships of those expelled unions. Under pressure of the growing red scare, the CIO also cut off ties and funding to Highlander and the Southern Conference, and some white CIO leaders in the South ignored their CIO international constitution that called for equal rights at work and in society.

Republican senator Joseph McCarthy, who replaced the progressive Democrat Robert La Follette, Jr., in Wisconsin, set the tone for the 1950s when he unleashed unfounded charges that Communists riddled the U.S. government, and undertook investigations that targeted labor and civil rights activists and anyone else he could think of to call a “red.” Attorney Roy Cohn, McCarthy’s aide, would go on to tutor real estate developer Donald Trump to continue in the art of the Big Lie and no-holds-barred attacks against anyone perceived to be an opponent. In Memphis, Mississippi senator James O. Eastland similarly used the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS) to condemn black and white leaders of Local 19 of the left-led Food, Tobacco, Agricultural, and Allied Workers (FTA) union, whose members had protested the frame-up and execution of Willie McGee, a black truck driver, in Eastland’s state.

In an interview, Memphis black Local 19 member Leroy Boyd told me that when employers called a white union leader a communist, it meant integrationist. “They knew how white men felt about another white man speaking up for the Negro. He was just branded a Communist.” He also said this did not deter most black workers, who supported integrationist CIO unions despite red-baiting.

The red scare helped to incite white worker and employer racism, however. In Birmingham, white Klansmen physically attacked members of the interracial (and left-led) Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers Union to defeat it. In Winston-Salem, North Carolina, HUAC hearings and a media red scare destroyed a thriving black-led tobacco workers’ union, the FTA. Anticommunist hearings, accompanied by media publicity, often held on the verge of elections in local industries, helped to wipe out interracial unions.

In 1955, with some of its best organizers removed, the CIO merged with the more conservative and white male–dominated AFL. The new AFL-CIO federation excluded supposed Communists, many of whom had helped to create the explosion of industrial unions in the 1930s and 1940s. In the 1950s, many unions stopped organizing new constituencies and concentrated on servicing their existing members. These tragic developments of the Cold War era cut short hopes that civil rights and labor organizing would move forward together. A number of progressive southern white Democrats lost their reelection campaigns, and the South moved toward becoming a bastion of white Republican power and antiunionism. The postwar red scare and white voting patterns would make King’s struggle for racial and economic justice much more difficult.

* * *

IN GRADUATE SCHOOL in the early 1950s, King wrote that he opposed communism as godless, and because it accepted violence and dictatorship, whereas nonviolence insisted that “the end is pre-existent in the mean.” His position on that would never change: one could only reach peaceful and democratic ends through peaceful and democratic means. He opposed all forms of dictatorship, but he also opposed crippling anticommunism and championed liberation movements against capitalist colonialism in the developing world. He held fiercely to the Social Gospel view that Christianity should help to liberate the poor and the oppressed. King wrote to Coretta that capitalism would probably be around for a long while but “I would certainly welcome the day to come when there will be a nationalization of industry.”

Coretta kept Martin’s letters and early sermons in a box in her basement for over thirty years after he died. Clayborne Carson reasoned that she probably feared that his candid thoughts about capitalism would be used by the American right wing to tarnish his legacy. The Kings lived in an era of unreasoning anticommunism, as governments and employers blacklisted people from employment and teaching simply based on their political associations, letters to the editor, or because they merely expressed sympathy for economic and social justice. Right-wing politicians and organizations would crusade against King throughout his adult life.

King’s powerful convictions and personal charms ultimately convinced Coretta to set aside her ambition to be a concert virtuoso. He insisted that she not go into the music or work world, but raise a family. In 1953 they married, and the next year King accepted a ministry at the relatively prosperous Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. With Martin finishing his PhD in philosophy and religion, tending to his congregation, writing and memorizing sermons that would later provide a base for much of his preaching, and with a child on the way, the Kings had a full life. But in Montgomery they ran into an appalling climate of white supremacy. Former slaves had built Dexter Avenue Baptist Church on foundations that had been a slave auction block, adjacent to the state capitol, the former headquarters for the southern Confederacy. The city’s black leadership was competitive and divided.

However, below the surface in Montgomery lurked a history of black resistance. King’s predecessor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Vernon Johns, had preached powerfully against segregation. King, like Johns, practically required his church members to join the NAACP and strongly supported the organization, but as a busy pastor he turned down a nomination as its chapter president. He said later that if someone had asked him to lead the Montgomery bus boycott he would have “run the other way.” History had other plans, however. The direct action of working-class bus riders transformed King’s kinship with the poor from a largely intellectual and family matter to a matter of lived faith.

The Montgomery movement erupted on December 1, 1955, with the arrest of Rosa Parks for refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white man. Jeanne Theoharis, in The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, documents how this modest seamstress, prompted early on by her husband’s participation in a Communist-led campaign in the 1930s to free the Scottsboro Boys, victims of a racial rape frame-up, had worked for years with E. D. Nixon, a member of A. Philip Randolph’s Pullman Porters Union and longtime civil rights activist, protesting the rape of black women, the lynching of blacks, and other atrocities. The grisly murder of fourteen-year-old African American Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, on August 28, 1955, for supposedly “speaking fresh” to a white woman, and the all-white-jury acquittal of his admitted racist killers, enraged African Americans and civil rights supporters everywhere. Members of the United Packinghouse Union attended the trial of Till’s killers and helped to organize huge protests in the North. Four days after attending a Montgomery protest of the Till lynching, and deeply affected by what she heard there, Parks defied the city’s segregation laws. Transportation racism reminded black people in Montgomery on a daily basis of racial injustice. White bus drivers had insulted, beaten, and even killed African Americans who resisted Jim Crow on the buses. Black people had to sit behind whites and move back to another row or stand up if one white person sat down in a row of seats that blacks already occupied. They had to pay their fare at the front of the bus, then go back out in order to enter from the back of bus. White bus drivers sometimes drove off and left them standing in the street.

For black workers and the black middle class of teachers and preachers, white supremacy in Montgomery blocked nearly all avenues to success. The humiliations and violence of bus segregation provided a daily insult. Two weeks before refusing to give up her seat, Parks had participated in an interracial discussion of how to organize resistance to segregation at Highlander Folk School. Her refusal to give up her seat was not a planned attempt to start a movement, but her calm courage touched off a remarkable, community-based movement that outlasted police violence, multiple bombings of churches and homes, and mass economic reprisals for 381 days.

Working-class people filled the ranks of the Montgomery movement. Eighty percent or more of black women in the wage economy were domestic workers. Black men did mostly janitorial and service work. Most working-class black people made too little to buy a car. Any possibility of a successful bus boycott depended on these workers. Preexisting organizations made a community boycott possible. During the boycott, Pullman porter E. D. Nixon through his union and connections to its president, A. Philip Randolph, saw to it that unions at the national level donated significant amounts of money to keep the movement alive. The black bricklayers’ union provided an office and a meeting place for an alternative transportation system operated by black taxi drivers and car owners. Jo Ann Gibson Robinson and the Women’s Political Council put out some 50,000 leaflets in the weekend after the arrest of Parks. The WPC had been building up a network of professional and working women who did much of the groundwork and organizing for the Montgomery protests. On Monday morning, December 5, 1955, when Coretta Scott and Martin King looked out their windows, they could see that no black people were riding the buses.

King explained several times during and after the Montgomery movement that he did not start it and it would have happened without him. But it is hard to imagine the movement in Montgomery without the galvanizing power of his preaching. According to volume three of the King Papers, in the Montgomery movement he “set forth the main themes of his subsequent public ministry: Social-Gospel Christianity and democratic idealism, combined with resolute advocacy of nonviolent protest.” In his first speech to a mass meeting, with only a few minutes to prepare, King proclaimed, “We, the disinherited of this land,” should “keep God at the forefront.” But “it is not enough for us to talk about love. . . . There is another side called justice.” King immediately identified this local struggle with larger issues and forces.

He cited the Supreme Court desegregation decision and used the leverage of the U.S. claim to be the leader of the “free world,” contrasting communist and totalitarian societies to the United States, where “the great glory of American democracy is the right to protest for right.” King also invoked the history of the labor movement: “When labor all over this nation came to see that it would be trampled over by capitalistic power, it was nothing wrong with labor getting together and organizing and protesting for its rights.” King defined the struggle as not only about race, but about “justice and injustice.” That would include the economic injustice that black Montgomery saw every day. King later would regularly emphasize the common roots and common tactics of the labor and civil rights movements.

The bus boycott began with a demand for simple courtesy within a segregated system, but the city’s refusal to negotiate led the movement to demand complete desegregation of the buses and the hiring of black bus drivers. White authorities tried to silence King and crush the movement. KKK members infested some white union locals and joined with white politicians, police, and businesspeople in a violent campaign of bombings, arrests, firings, and intimidation. Mississippi senator James Eastland led a rally of 10,000 whites with hateful, violent rhetoric; all of the city council members promptly joined the White Citizens Council, founded by white-supremacist business and political leaders in Mississippi to resist the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision. George Wallace, a Populist who claimed he got “outniggered” in an election campaign in the 1950s, filled Alabama with divisive racist rhetoric, and as governor in 1963 would vow “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

In this brutal and racist climate, King and others experienced death threats, arrests, and bombings. On January 26, 1956, police arrested him for supposedly going five miles over the speed limit, and took him on a harrowing ride into a desolate part of town where he thought he was about to be “dropped off” and killed like so many others. On January 27, following a stint in a Montgomery jail and a midnight phone call threatening the lives of his family, King had a crisis of fear. In a moment that changed his life, he felt the power of the Lord promising “never to leave me alone.” From then on, he vowed to always push on despite his fears.

On January 30, Coretta with her baby and her sister were sitting in the front room when they heard a noise outside and quickly moved away. Otherwise they would have been maimed or killed as a bomb blew off the front of the house. Famously, King returned from a mass meeting to find a group of angry, armed African Americans gathered outside his wrecked home, ready to fight, and in a remarkably calm voice dispersed the crowd by invoking love and nonviolence as more powerful than bombs. “We are not hurt and remember that if anything happens to me, there will be others to take my place,” he told them.

Out of necessity King committed himself to nonviolent discipline. He saw that the use of weapons by supporters outside of King’s home would have led to a massacre by the police and defeat for the movement. He also understood that black southerners on an individual level often had to protect their families and homes and that most black southerners did not accept nonviolence as a general principle. Many black male military veterans agreed with black activist Robert F. Williams in North Carolina that nonviolence was a form of suicide. As civil rights activist and writer Charles Cobb later put it, “That Nonviolent Stuff’l Get You Killed.” The bombing of the home of Harry and Harriette Moore in Brevard County, Florida, on Christmas night 1951, killing both of them, was but one example of the violence inflicted on black people who agitated for voting and civil rights. King in theory did not oppose using arms to defend his family, and he didn’t condemn others for doing so. The right to self-defense when personally attacked, he would later write, “has been guaranteed through the ages by common law.” Few suggested that individuals should not protect themselves, but he would always argue that taking up arms in a mass movement would not work for a minority population against a heavily armed state and would drive away others who might otherwise support a movement for change.

On February 1 King and Ralph Abernathy tried to get pistol permits, but the county sheriff denied them. That night vigilantes exploded a bomb in the yard of E. D. Nixon. Unarmed black men guarded King’s home each night. On February 10 white supremacists circulated a “Declaration of Segregation” at the White Citizens Council meeting, declaring, “When in the course of human events it become necessary to abolish the Negro race, proper methods should be used. Among these are guns, bow and arrows, sling shots and knives.” But despite constant threats of violence against them, people in the Montgomery movement followed King’s teaching that they should not take up arms, both for moral reasons and because the superior weaponry of the state and white vigilantes would surely crush them if they did.

On February 21, a grand jury indicted King and over one hundred other movement leaders under a state antiboycott law. The indictments created national media attention that drew increased donations and support from outside Montgomery. On the same day, Bayard Rustin arrived, to provide support and counsel to King on how to conduct a nonviolent campaign. Rustin was the African American Quaker nonviolence advocate who Coretta Scott King had heard speak while in college. Like many radicals of the era, Rustin had joined the Young Communist League in his youth, but he became an independent socialist aligned with the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). lts leader was A. J. Muste, a man of conservative Dutch Reformed upbringing who organized strikes and labor education for unions in the 1920s and 1930s and remained one of the most militant advocates of nonviolent direct action. Rustin followed Muste’s path and went to prison for sixteen months rather than fight in World War II. In 1947, Rustin participated in a “freedom ride” to challenge bus segregation in interstate commerce, ending up on a chain gang for a month in North Carolina. He had been protesting segregation and speaking about nonviolence long before Montgomery.

Rustin lived in New York City and had close ties with other leftist and labor activists there. One was A. Philip Randolph, the dean of labor and civil rights in America. Another was Stanley Levison, a well-to-do left-wing New York City businessman and attorney who had raised money for civic and social justice causes, some of them linked to the Communist Party. Rustin and Levison became fund-raisers, strategic advisers, and ghostwriters for King. Despite false accusations by the FBI, neither Rustin nor Levison at the time they met King belonged to the Communist Party. Rustin had left the Young Communist League years ago, and Levison said he never joined the CP although he supported left-wing causes. They both knew their way into the complicated world of American labor and would especially help King link up with unions and to construct his labor speeches. Levison and Rustin also linked King to Ella Baker, a veteran civil rights and community organizer on the left in New York City politics who had traveled the South building up the NAACP during the 1940s. In February 1956 Levison, Rustin, and Baker formed a group called In Friendship to raise funds for the southern civil rights movement, and they immediately began to raise funds to support the Montgomery boycott.

Historian Thomas Jackson writes that King early on became linked to a “vanguard of activists who were vigorously pushing a combined race-class agenda in the late fifties.” Rustin, Levison, Baker, Randolph, and other civil rights and labor leftists in New York discussed the Montgomery movement in great detail and this group sent Rustin to meet King. But they feared that as a homosexual who spent time in jail for his sexuality and as a leftist radical, Rustin could damage King’s reputation. Rustin counseled King on the ideas and principles of nonviolent direct action, as an alternative to the idea of “passive resistance,” and secretly left town before white supremacists could discover his presence. Rustin wrote an article on behalf of King for an April issue of Liberation magazine, a journal of the left, and intermittently continued to provide guidance, writing, and organizing support, both as a staff to King and as an unofficial advisor.

Although outside help from the New York left, donations, and mass media publicity helped to make a victory possible in Montgomery, the people themselves provided the key to success. Black women, cooks and maids, walked miles to and from work, and sometimes took rides from white housewives who did not want to lose their labor. Over 381 days, African Americans in Montgomery carried on a nonviolent bus boycott. After many trials and tribulations, a U.S. Supreme Court decision finally outlawed bus segregation in Montgomery, and King and the movement declared the boycott over on December 26, 1956. After that victory, someone fired into the front door of the King home with a rifle. King told a mass meeting that night, “I would like to tell whoever did it that it won’t do any good to kill me,” because “we have just started our work.”

Freedom riders would later desegregate transportation across the South; some would sacrifice their lives. The movement started and ended with the courage and persistence of everyday people walking many miles to and from work and standing up to persecution. The Montgomery boycott’s economic demands included the right to go to work in dignity and for black workers to be employed as bus drivers. Virtually every major struggle of the era, James Lawson told me in an interview, embodied a demand for economic justice as well as civil and voting rights.

Over the course of the Montgomery campaign, King came to use the term “nonviolent resistance,” a phrase adopted from Mohandas Gandhi. The idea was simple: that people could end their oppression by refusing to participate in the system that oppressed them. A 1957 Christian Century magazine article, drafted by Bayard Rustin and elaborated by King in his first book, Stride Toward Freedom (1957), explained the basic tenets of nonviolent struggle. King turned to history to explain that slavery and the failed promise of Reconstruction, followed by the imposition of Jim Crow, had created a “negative peace” based on the suppression of black personhood. When blacks no longer submitted to it, they gained a “new sense of self-respect and sense of dignity.” He observed that this dynamic appeared throughout the former European colonies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, where “the struggle will continue until freedom is a reality for all the oppressed peoples of the world.” King always saw the freedom struggle as world wide.

The question was not if there would be change, but how oppressed people would wage the struggle. King provided the answer, based on Gandhi: “Someone must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate.” King explained that nonviolent resistance was not passive but must be active, spiritually and physically, yet without inflicting harm on others: “The nonviolent resister seeks to attack the evil system rather than individuals who happen to be caught up in the system.” While “the aftermath of violence is bitterness,” he wrote, “the aftermath of nonviolence is reconciliation and the creation of a beloved community.”

King said implementing nonviolence required the practice of agape love. As opposed to erotic or familial love, agape love “means understanding, redeeming good will . . . an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return,” and the belief “that God is on the side of truth and justice.” He wrote that a better way of human relations “comes down to us from the long tradition of our Christian faith,” in which “Christ furnished the spirit and motivation,” while “Gandhi furnished the method.” People of many faiths—or no faith—could follow a philosophy and practice of nonviolent resistance to violence, oppression, and economic exploitation. King believed he had found a moral framework to guide a universal struggle for justice from which all people could benefit.

News of Montgomery electrified James Lawson, who was at that time on a mission for the Methodist Church in India. A conscientious objector to war who had spent time in prison during the early Korean War as a draft resister, Lawson realized that the Montgomery movement could be replicated in other places. Indeed, it set the stage for the next decade of locally based freedom struggles across the South, from Albany, Georgia, to St. Augustine, Florida, from Mississippi to Birmingham to Selma, from Chicago to Memphis. Lawson pointed out to me that “the great man” theory does not explain King’s role in history; that leaders are made, not born, through interaction with people during social-movement organizing. Ella Baker, one of the most influential grassroots organizers of the era, likewise explained that King did not make the freedom movement, the movement made King. Indeed, it transformed him from an intellectual follower of the black Social Gospel and nonviolence into a dedicated social-movement leader.

In Montgomery, a blacklist forced an unemployed Rosa Parks and her husband to leave for Detroit, while King began to travel and speak all over the country. E. D. Nixon complained that while King became a famous speaker, the local movement fell apart. King would forevermore be accused of taking the limelight. Indeed, King could never fully meet the needs of a congregation and a local movement while also addressing a national audience. His fame and personal success led to contradictions. King had his limitations. But his gifts of oratory and insight would energize both the freedom movement and the labor movement, and leave an indelible imprint on American history.